Abstract

Reproduction is controlled by a sequential regulation of hypothalamo-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. The HPG axis integrates multiple inputs to maintain proper reproductive functions. It has long been demonstrated that stress alters fertility. Nonetheless, the central mechanisms of how stress interact with the reproductive system are not fully understood. One of the major pathways that is activated during the stress response is hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. In this review, we discuss several aspects of the interactions between these two neuroendocrine systems to offer insights to mechanisms of how the HPA axis and HPG axes interact. We have also included discussions of other systems, for example GABA-producing neurons, where they are informative to the overall picture of stress effects on reproduction.

Keywords: stress, CRH, reproduction, sex steroids

1. Overview

Reproduction is required to maintain species and is regulated by complex interactions among multiple systems. In vertebrates, reproduction is controlled by the hypothalamo-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. This axis is regulated by both external and internal inputs such as season, food availability, age, steroids and stress. The last of these is mediated in part via another neuroendocrine axis, the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, along with other central and peripheral elements. The primary focus of this review is on how the HPG and HPA axes interact, including at the level of the brain, examining both stimulatory and inhibitory effects of exposure to stress or stress mediators on reproductive neuroendocrine function. Stress may affect HPG axis output through additional pathways beyond the HPA axis, and where there is sufficient information on the stress-reproductive interactions for these other pathways we have included a discussion of these elements.

2. The HPG axis

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons form the final common pathway that integrates central control of-reproductive processes in vertebrates. The somata of GnRH neurons are located in the midventral preoptic area (POA) and hypothalamus and most project axons to the median eminence, where GnRH is released near the primary capillaries of the hypophyseal portal system (1). There are two modes of GnRH release, pulsatile and surge. Pulsatile release of GnRH occurs during the majority of the female reproductive cycle and is the only known mode of release in males (2,3). During the late follicular phase in females, GnRH release switches from pulsatile to a continuous elevation or ‘surge’ lasting several hours. This GnRH surge is critical for ovulation in most species (4–7). GnRH binds to its receptors on the pituitary gonadotropes where it stimulates synthesis and secretion of the gonadotropins, luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) (8–10). LH and FSH activate act on the gonads to regulate both gametogenesis and steroidogenesis. Gonadal steroids feed back to the brain and pituitary to regulate GnRH and gonadotropin secretion, respectively (11–14).

While they serve as the final central output pathway for the primary neuroendocrine hormone regulating pituitary gonadotropin release, GnRH neurons are downstream of a larger network that is still being defined. Elements of control of these cells by many factors that alter GnRH and subsequent LH release are likely processed to a considerable extent via these afferent networks. This includes the physiologic control exerted by gonadal steroid feedback; GnRH neurons do not express detectable levels of most sex steroid receptors other than estrogen receptor β (ERβ) (15–19), making it likely that sex steroid effects are mediated by afferent neurons expressing these receptors. Similarly stress regulation of GnRH neuron output as well as sex steroid modulation of these interactions likely also occurs in large part via afferent networks.

With regard to the afferent network, kisspeptin neurons are a major candidate for conveying sex steroid feedback to GnRH neurons (20,21). Kisspeptin neurons express estrogen receptor α (ERα) (22), which is known to be important for regulating both the pulsatile and surge modes of GnRH release (23,24). Kisspeptin is a potent activator of GnRH neuron activity, and GnRH and gonadotropin release (25–28). In rodents, kisspeptin neurons are found in two major regions in the hypothalamus: the anteroventral periventricular (AVPV) nucleus and the arcuate nucleus (29). Kisspeptin neurons in the arcuate nucleus also express neurokinin B and dynorphin A (often called KNDy neurons). The current emerging consensus is that arcuate kisspeptin neurons are critical for negative feedback regulation of pulsatile GnRH release (30), whereas AVPV neurons are critical to the generation of the surge mode of GnRH release (21,31,32) (reviewed in (33)). It is important to point out that interactions among arcuate and AVPV kisspeptin neuronal populations (34), as well as influence from non-kisspeptin neurons on both kisspeptin neurons and GnRH neurons (35,36) cannot be excluded.

3. Stress and the HPA axis

In 1936, Hans Selye first defined ‘general adaptation syndrome’ (37), which was later renamed ‘stress’. General adaptation syndrome referred to ‘the non-specific neuroendocrine response of the body to a noxious insult (38). Stress activates several pathways to help maintain homeostasis including a noradrenergic pathway originating in the locus coeruleus, epinephrine release from the adrenal medulla, and the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis that regulates the synthesis of glucocorticoids (reviewed in (39,40)). This review will focus primarily on relationships between the HPA and HPG axes.

Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH, also called corticotropin-releasing factor or CRF), a 41-amino-acid peptide sequenced in 1981, plays a major role in the response to stress (41,42). CRH regulating the HPA axis is largely synthesized and released from neurons in the parvocellular subdivision of the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus and project to the median eminence, where the secretion into pituitary portal blood occurs (43). Although our primary emphasis is on the HPA axis, it is important to point out that CRH is also expressed in other parts of the brain, such as the central nucleus of amygdala projecting to hindbrain regions that control the autonomic responses to stress (44,45), and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), which is implicated in anxiety-related behaviors (46,47). Arginine vasopressin (AVP) is also synthesized in the parvocellular PVN and can augment the response to CRH (48). Magnocellular neurons in PVN and supraoptic nucleus also release AVP, typically in response to increases in blood osmolarity (49), but this source does not appear to be involved in the stress response (50). CRH acts on pituitary corticotropes to stimulate secretion of adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH) (51,52), which triggers the synthesis of glucocorticoids (mainly corticosterone/cortisol) by the adrenal cortex (detailed review in (53)). Glucocorticoids exert negative feedback effects on the pituitary and hypothalamus to regulate the activity of the HPA axis (54).

4. CRH receptors and other ligands

CRH receptors are class-B, or secretin family, G-protein-coupled receptors (55,56). There are two types of CRH receptors (CRHR), CRHR1 and CRHR2, which share 70% amino acid homology (55,57). The distribution of these two receptors is different. CRHR1 is expressed primarily and widely in the brain, in regions including the cerebral cortex, amygdala, hippocampus, and hypothalamus, as well as in pituitary corticotropes (58–60). CRHR2 is expressed mostly in peripheral tissues including heart and skeletal muscle though there is some brain expression in the lateral septum and hypothalamus (58–60). In addition to CRH, both receptors also bind a family of three CRH-related peptides called urocortins (61–63) though with different affinities. CRHR1 has a higher affinity for CRH than CRHR2, but both receptors bind urocortin I with similar affinity (64,65). Urocortin I is primarily expressed in the Edinger-Westphal (EW) nucleus in response to stress induction (66,67). Urocortin II and urocortin III are considered to be endogenous ligands of CRHR2 due to the high affinity of CRHR2 for both of these peptides. Urocortin II and III have thus been used as tools to test independent activation of CRHR2 as CRHR1 has little to no affinity for these peptides (62,63). Urocortin II is found in areas implicated in the stress response such as the PVN, supraoptic, and the arcuate nucleus (68). The expression of Urocortin II in the arcuate nucleus raise the interesting possibility of local communication with KNDy neurons to regulate reproductive functions. Urocortin III mRNA is found in several regions of the brain including median preoptic nucleus, posterior BNST, and dorsal medial amygdala (69). Urocortin III-immunoreactive fibers project to ventromedial nucleus and arcuate nucleus (70), with the latter again suggesting a possible connection to arcuate KNDy neurons. For further information on possible endogenous effects of urocortins in the HPA axis, the reader is referred to reviews by Zorilla and Koob (71).

5. The HPA axis response to stress

One of the physiologic responses to stress is the release of CRH near the hypophyseal portal vessels. CRH binds to CRHR1 on the pituitary corticotropes, which stimulates secretion of ACTH to drive downstream synthesis and secretion of adrenal glucocorticoids. The role of CRHR1 in the activation of the pituitary during the stress response was confirmed in CRHR1-deficient mice, which exhibit an impaired HPA axis response to stress with minimal ACTH release, and little to no corticosterone production (72). Consequently, these mice have reduced anxiety-related behaviors (73,74). In contrast, mice that lack urocortin I, which also binds CRHR1, have a normal corticosterone rise in response to restraint stress (75), despite the demonstrated ability of this peptide to increase glucocorticoids when exogenously administered (61). These observations imply that CRH, rather than urocortin I, is the primary endogenous regulator of the CRHR1-mediated stress response of the HPA axis, although redundancy in this system cannot be excluded.

Compared to CRHR1, the function of CRHR2 in the HPA axis during the stress response is more complex. One hypothesis is that CRHR2 counteracts the functions of CRHR1 by reducing the stress response (76). Consistent with this, mice lacking CRHR2 exhibit hypersensitivity to stress induction and a slower return of corticosterone to pre-stress levels (77,78). Intracerebroventricular (ICV) or intravenous (IV) injection of urocortin III (which binds essentially exclusively to CRHR2 at physiologic concentrations) increased ACTH and corticosterone levels compared to the control group (79), suggesting activation of CRHR2 may induce HPA axis activity; whether or not this occurs during stress in response to endogenously-released urocortin III is unknown. The effects of the CRHR2 agonist urocortin III on hormonal responses in the HPA axis were shorter duration than in response to CRH and required higher concentration of urocortin III (80). Therefore, Jamieson and colleagues speculate that activation of CRHR2 might play a role in modulating role in the stress response of the HPA axis rather than being a primary mediator (81). It is also important to point out that the different drug treatments in these studies may have different levels of efficacy at the doses used. These findings suggest that activation of CRHR1 vs CRHR2 might lead to different physiological responses in the HPA axis during stress. This is of interest to interactions between the HPA and HPG axes, because while stress has primarily been reported to inhibit various reproductive processes, activation of these processes by acute stress has also been observed. It is also important to point out that expression of one or more CRH receptors does not in and of itself provide proof a cell type is involved in mediating the effects of stress on the reproductive neuroendocrine or any other system. But it opens the possibility that the expressing cell is able to respond to CRH and urocortins and may be involved in mediating stress or other physiologic roles of those ligands.

6. Inhibitory effects of stress on reproductive neuroendocrine function

Deleterious effects of stress exposure on reproductive function have been demonstrated in several species, with a majority of neuroendocrine studies in primates, sheep and rodents (82–88). Several modalities for inducing a stress response have been used, including metabolic, immunological, psychosocial, and physical; these stressors alter timing of puberty in both males and females (89–93) and disrupt female reproductive cycles (94–99). The inhibitory effects of stress on reproduction are likely a result of disruption of gonadotropin secretion subsequent to changes in GnRH output (whether mediated directly at those cells or via afferent networks). In particular, the effects of stress or specific HPA hormones on LH release are informative, as the frequency of LH pulses provides a window to the central regulation of HPG axis. It is important to keep in mind that studies manipulating levels of hormones of the HPA axis (e.g., CRH, ACTH, and glucocorticoids), while informative, are not equivalent to stress exposure as stress can also stimulate multiple other pathways. Nonetheless, treatments that block or mimic the actions of different components of the HPA axis are useful for addressing necessity and sufficiency of components of the HPA axis in stress-induced alterations of the HPG axis.

Glucocorticoids, the end-organ product of HPA axis activation, typically suppress gonadotropin secretion, but outcomes are variable, and several factors need to be considered when interpreting these results. In ovariectomized (OVX) ewes, cortisol treatment that mimics the levels achieved during immunological stress suppresses LH pulse amplitude but not frequency (100–102), and had no effect on GnRH pulse amplitude or frequency (101,102), indicating cortisol acts at the pituitary in this model to inhibit the response to GnRH, rather than centrally to affect its release. In contrast, cortisol suppressed both GnRH and LH pulse frequency in follicular-phase ewes (103–105). This suggests that circulating ovarian steroids present in the latter study influence the response of the HPG axis during stress; this will be discussed in detail below. In OVX female rats with low physiological estradiol replacement (diestrous levels), neither acute nor chronic treatment with corticosterone altered LH pulse frequency or amplitude (106,107), whereas in intact male rats, chronic corticosterone treatment lowered serum LH levels in single terminal samples (108). Chronic corticosterone treatment suppressed LH pulse frequency in OVX+E (100 ng estradiol, negative feedback model) mice but not in OVX mice (109); this mechanism appears to involve KNDy neurons at some point as cFos expression in these cells is reduced in corticosterone-treated mice, suggesting reduced activity. The difference in LH responses between these studies may be attributable to sex, corticosterone dose, which was lower in the former, and/or LH sampling regimen. In castrated male monkeys, chronic cortisol treatment suppressed LH and FSH in daily, or alternate daily, samples (110). This suppression is likely at the hypothalamic level because gonadotropin secretion in response to exogenous GnRH was unaffected. In early follicular phase women, chronic hydrocortisone treatment suppressed LH pulse frequency (85), whereas acute hydrocortisone treatment on the day of sampling did not affect LH or FSH levels in either early follicular phase women or in men (111). Here the discrepancy in results might be due to treatment duration or to different blood sampling intervals affecting the ability to detect LH pulses. Thus while glucocorticoids suppress LH secretion in most conditions, the mechanisms (central vs pituitary) depend on the species, duration of treatment, and gonadal steroids (reviewed in (87,112)).

The effects of CRH on also vary with model studied. Inhibitory effects of CRH administered ICV or into the median eminence on LH pulse frequency and amplitude have been observed in monkeys, ewes and rats (113–116). A recent study using a chemogenetic approach to stimulate CRH neurons in the PVN resulted in suppression of LH pulse frequency in OVX mice (117). Notably, optogenetic stimulation of the CRH neurons in the PVN did not affect firing activity of KNDy neurons, suggesting reduced activity of these cells may not be mediating this suppression (117). While a critical role of CRH signaling in this scenario is likely to induce a glucocorticoid rise, IV injection of CRH still inhibited LH pulse frequency and amplitude in adrenalectomized monkeys despite these animals being unable to produce adrenal glucocorticoids (115). This indicates that CRH itself can act on the reproductive system independent of glucocorticoids. CRH receptors, at least in part, mediates stress effects centrally and/or on the pituitary gonadotrope as pretreatment with non-specific CRHR antagonists (i.e., blocking both CRHR1 and CRHR2) prevents stress-induced suppression of LH pulses in castrated male rats, OVX+E rats, and OVX monkeys (83,113,118,119). Pretreatment with non-specific CRHR antagonists also prevents suppression of LH pulse frequency caused by interleukin-1α (IL-1α) in OVX monkeys (120). Different types of stressors appear to act on the reproductive system via different CRHR subtypes; in vivo treatment of OVX+E (diestrous level) rats with CRHR1- or CRHR2-specific antagonists revealed that insulin-induced hypoglycemia and immunological stress act through CRHR2, whereas restraint-induced stress involves both CRHR1 and CRHR2 to suppress LH pulse secretion (119,121). Administration of a CRHR2 antagonist, astressin-2B, ameliorated the effect of stress (restraint, insulin-induced hypoglycemia, or immunological stress) on LH pulse suppression but not the stress-induced corticosterone rise, consistent with the latter being mediated by CRHR1 (119,121). This suggests that activation of CRHR2 can alter secretion of LH independent of the HPA axis. In a complementary study, ICV administration of the CRHR2-specific agonist urocortin II suppressed LH pulse frequency. Interestingly, this effect was delayed by over an hour compared to the effect of stress itself, suggesting other endogenous systems activated by stress have a more rapid effect. An anti-urocortin II antibody blocked the inhibitory effect of restraint stress on LH in single point samples but did not alter either ACTH or corticosterone levels (122), suggesting that urocortin II, via CRHR2, likely acts at the central level to alter reproductive functions. McCosh and colleagues provide further information on how neural mechanisms may differ with type of stressor (86).

7. Stimulatory effects of stress on reproductive neuroendocrine function.

Stress exerts stimulatory effects reproductive neuroendocrine function in some conditions. In male rats, the initial exposure to restraint stress increased plasma LH levels within 15-30 min of stress onset, after which levels declined toward pre-stress baseline; of note sampling was terminated 50min after stress exposure in this study, precluding determination of a subsequent inhibitory effect (123). This acute increase in LH secretion disappeared after 10 days of exposure to the same stress, suggesting a change in the stimulatory response to stress overtime (123). One caveat of this study is the lack of nonstress control group for comparison. The level of LH after restraint induction was, however, greater than the prestress baseline. Several lines of evidence indicate activation of CRH receptors can activate the HPG axis under certain conditions. First, ICV administration of CRH had no effect on LH pulse frequency in OVX ewes (124), but increased LH pulse frequency in both gonadectomized male or female sheep that were steroid-replaced (125). Further, central injection of CRH increased LH pulse amplitude in castrated rams both with and without testosterone replacement (126). Second, IL-1α increases LH release 3h after administration in OVX monkeys with a positive feedback level of estradiol; IL-1α was administered the day after LH surge induction, thus this is likely not attributable to the positive feedback effects of estradiol on LH per se. Pretreatment with a CRHR antagonist that blocks both CRHR1 and CRHR2 prevented the stimulatory effect of IL-1α on LH levels in this paradigm. The timing of the IL-1α-induced increase in LH suggests multiple systems and mechanisms are engaged before the eventual increase in circulating LH (127). Third, restraint stress of estradiol-primed OVX rats induced a premature increase in LH before the typical late afternoon surge; pretreatment with a CRHR1, but not CRHR2, antagonist abolished this stimulatory effect on LH secretion in female rats, implying activating these receptors likely has different consequences for LH and presumably GnRH release (128,129). Together these observations suggest that activation of CRH receptors, in particular CRHR1, can enhance LH secretion under certain conditions. They further indicate the high physiologic levels of estradiol typical of the late follicular phase/proestrus may prime the reproductive neuroendocrine system to respond to stress with activation.

Stimulatory effects of stress sometimes occur in a subset of animals. For example, examination of the individual rat data in (121) reveals that restraint stress during CRHR2 antagonist treatment caused a transient increase in LH pulse amplitude in the representative data shown; whether or not this was a consistent observation is not known. Similarly, one of four monkeys subjected to 6h restraint showed increased LH pulse frequency and amplitude within 30 min of stress onset during both follicular and luteal phases (130). In another study, although IV injection of CRH acutely suppressed hypothalamic multiunit activity (MUA) volleys concomitant with the suppression of LH pulse frequency in majority of the monkeys, CRH caused premature hypothalamic MUA volleys in 5 of 15 OVX monkeys tested (114); these data were noted to be excluded from interpretation by the authors even though one third of animals exhibited this response. If such observations are commonly regarded as technical errors and excluded from analysis, this could alter interpretation of the integrative effects of stress on reproductive neuroendocrine function. These data suggest potential biphasic effects of stress on reproductive neuroendocrine function with an initial acute stimulation followed by more prolonged suppression.

It is important to point out that the acute activation of GnRH/LH release by the components of the HPA axis should not be regarded as stimulating reproduction in terms of the number of offspring produced. Rather, it is likely these stimulatory hormonal responses would have adverse effects on fertility. For example, premature ovulation could result in mistimed fertilization or improper preparation of the uterus.

8. Influence of sex steroid hormones on the stress response

It is well established that sex differences exist in HPA axis function both under unstressed control conditions and during the stress response. Female rats produce both greater basal levels of ACTH and corticosterone and greater increases in these hormones in response to stress than males (131,132). There are several factors that underlie these sex differences, including gonadal steroid hormones. Estradiol alters the function of the HPA axis at every level. CRH neurons in the PVN express ERβ (133,134) and can thus respond directly to estradiol as well as be influenced via steroid-sensitive afferents. Rats with high circulating estradiol (OVX+E and proestrous) had greater basal ACTH and corticosterone levels in nonstress conditions in comparison to OVX or diestrous rats (135,136); furthermore the corticosterone rise in response to stress was also greater in these animals (135,137). Both CRH and CRH receptors are regulated by estrogens and both CRH and the CRHR genes contain estrogen-responsive elements (138,139). CRH mRNA expression in the PVN is higher in OVX+E than OVX rats (107,136). Basal CRHR1 and CRHR2 mRNA expression in the dorsal raphe was also higher in female than male rats (140). Stress-induced expression of CRHR1 in females was greater in the PVN during the morning of proestrus (high estradiol) than diestrus (lower estradiol), and removal of ovaries decreased basal CRHR1 and CRHR2 mRNA expression in hippocampus in female rats (141,142). Thus, estradiol-induced increases in CRH and CRHR could prime the central arm of the HPA axis to produce a greater output in response to stress, and upregulate target tissue response, respectively.

In contrast to estradiol, androgens typically suppress the stress response. Castrated males produce a greater corticosterone rise in response to stress than intact males in several species (131,143,144). Androgen replacement by dihydrotestosterone (DHT), a non-aromatizable androgen, restored the corticosterone rise to that observed in intact male rats (144). The increase in corticosterone secretion observed in castrated males might be attributable to central effects of gonadal steroids as castrated rats have increased basal hypothalamic tissue CRH levels, increased CRH immunoreactivity, and increased neuronal activation detected by cFos (an indirect marker indicating neuronal activation) in CRH neurons in the PVN as compared to intact rats (145,146). DHT replacement reduced stress-induced activation of neuroendocrine cells detected by cFos expression in the PVN (intact males were not examined) and also suppressed CRH and AVP mRNA expression in the PVN compared to unreplaced castrated rats (147). Together, these results indicate that androgens often play an opposite role to estrogens and that sex steroids are an underlying cause in sex differences in the stress response. The role of androgens in the stress response has recently been reviewed in detail (148).

The modulation of the reproductive system by stress is also affected by gonadal steroids. In rats, the inhibitory effects of insulin-induced hypoglycemia or food deprivation on LH pulse frequency were stronger in OVX+E than OVX rats (107,149,150). Immunological stress with IL-1α in female monkeys is highly dependent upon gonadal milieu. During the mid-follicular phase, IL-1α generated a robust increase in the mean circulating LH concentration five hours after injection, whereas similar treatment in early-follicular-phase monkeys, when estradiol is lower, had no effect. Interestingly, the same treatment in OVX monkeys suppressed LH secretion (151,152). Recent studies in mice demonstrated that IL-1β suppressed LH pulse frequency in OVX+E but not OVX animals (153). The different outcomes between these studies might result from the different in species (monkey vs mouse) and different stress mediator (IL-1α vs IL-1β). In postmenopausal women receiving transdermal estradiol replacement, inflammatory stress or ACTH infusion increased mean hourly plasma LH concentrations 3-fold compared to baseline (154). Estradiol may augment stress effects by amplifying the actions of CRH. OVX+E rats exhibit a stronger suppressive effect of CRH on LH pulse amplitude and frequency than OVX rats (113). In vitro, bath-applied CRH exerts both stimulatory and inhibitory effects on GnRH neuron firing activity in brain slices from unstressed mice depending on the type of CRHR activated. These effects were observed in GnRH neurons from OVX+E mice during estradiol positive feedback (akin to the GnRH surge, see below) but not cells from OVX mice (155). The inhibitory effect of corticosterone on the HPG axis are also influenced by estradiol as chronic corticosterone treatment suppressed LH pulse frequency, and also decreased cFos expression in arcuate kisspeptin neurons in OVX+E mimicking the diestrus but not in OVX mice (109). Together, these data suggest that estradiol potentiates the effects of stress on the reproductive system, indicating bidirectional interactions between the HPG and HPA axes.

9. Effects of stress and HPA hormones on the GnRH/LH surge

In addition to disruptions of homeostatic (i.e., negative) feedback, stress can interfere with estradiol positive feedback needed to generate ovulation. In rats, restraint for 5-7 hours starting 0-2 hours before the typical onset of the LH surge blocked the surge in half of the animals and decreased ovulation rate (156). In mice, the LH surge was blocked in a majority of animals in response an acute layered psychosocial stress paradigm initiated on the morning of proestrus and completed before typical surge onset (157). An LH surge was also not detected on the next day suggesting that stress did not delay LH surge by 24h, but either completely blocked the generation of the LH surge or altered its timing sufficiently to be out of the sampling window (157). This stress-induced blockade was on central estradiol action, not production of the estradiol rise as all proestrous mice exhibited typically increased uterine mass (>100mg, attributable to estradiol action) and the estradiol-induced LH surge in OVX+E (daily surge model) mice was also blocked (157).

The effects of stress on the GnRH/LH surge result from activation of multiple levels of the HPA axis. Glucocorticoids released during the stress response may inhibit the LH surge. Cortisol infusion in ewes during the early-to-mid follicular phase blocked the LH surge in half of the animals and delayed the surge in the remainder (103). However, in this work, the effects on the LH surge might result from the reduced or absent follicular phase estradiol rise attributable to suppressed pulsatile LH release (103). Further experiments have shown suppressive effects of cortisol on the estradiol-induced LH surge in both mice and sheep (95,158,159), indicating an additional effect of glucocorticoids to interrupt the positive feedback effects of estradiol. CRH might also be involved in stress-induced suppression of the LH surge. Continuous infusion of CRH for six hours starting an hour before the presumed onset of the LH surge or a single injection of CRH near surge onset reduced LH surge amplitude in proestrous rats (160). Of note, cortisol was not monitored in this study but would be expected to increase; CRH is likely not be the only mediator involved in the stress-induced suppression of the LH surge as restraint stress still effectively blocks the LH surge in CRH-deficient mice (161).

10. Candidate central neurons for mediating stress-reproductive interactions

10.1. GnRH neurons

GnRH neurons are central neuroendocrine output neurons largely, although not exclusively, responsible for determining pituitary gonadotropin release. As such, modulation of their output is quite likely by any endogenous or exogenous signal that modifies gonadotropin release via central mechanisms (i.e., that do not act exclusively at the pituitary itself). A larger question is whether endogenous and/or exogenous signals are acting directly upon GnRH neurons, by modifying one or more inputs to these cells, or both.

Evidence indicates that processes within GnRH neurons can be modulated by stress or treatment with stress-related hormones. Follicular-phase monkeys that were classified as stress-sensitive (exhibited suppression of menstrual cycles and sex steroid levels during the first cycle of stress exposure) had less GnRH fiber immunostaining in the median eminence, but a higher number of neurons expressing GnRH mRNA in the medial basal hypothalamus, compared to monkeys that were resistant to stressors (continued to show normal menstrual cycles and changes in sex steroids) (162). One possible interpretation is that chronic mild stress reduces transport of GnRH from cell bodies to axon terminals, thereby decreasing the releasable pool of GnRH. Whether this is a direct effect of the stress paradigm on GnRH neurons cannot be determined from this study, and there were notably changes in other brain regions, including serotonergic systems and CRH expression, suggesting multiple mechanistic pathways may be involved.

Anatomical evidence shows that CRH-containing fibers in humans (163) and rats appose GnRH neuron cell bodies (164). To ask if effects of CRH may be direct on GnRH neurons, several labs have examined CRHR expression in these cells, but results are mixed. Single-cell RT-PCR analysis showed CRHR1 mRNA in one-fourth of GnRH neurons from female mice and approximately 30% of GnRH neurons exhibited CRHR immunoreactivity although the antibody used did not distinguish between CRHR subtypes (165). Neither CRHR1 nor CRHR2 mRNA were enriched in GnRH neurons from male or female (intact or gonadectomized) mice determined by translating ribosome affinity purification combined with RNAseq (166); lack of enrichment does not indicate absence and this method has reduced sensitivity with low copy-number transcripts such as GPCRs. Of note, CRHRs were not detected in cells identified as GnRH neurons from male and female mice determined by single-cell RNA-seq transcriptional profiling, although this approach may not thoroughly sample the population as only 15 GnRH neuron were detected (167). In situ hybridization of tissue from female rats or male mice also did not detect either CRHR1 or CRHR2 in GnRH neurons (168,169). Likewise, immunofluorescence studies using CRHR1-GFP reporter mice showed no colocalization between CRHR1 and GnRH neurons in either male or female mice (169,170). These discrepancies might result from the species, sex, and methodical differences in each study. Cholera toxin B, a retrograde tracer, was injected into the POA near the soma of GnRH neuron among other cell types, but none of the labeled cells projected near CRH neurons in the PVN, the bed nucleus of stria terminalis, or the central amygdaloid nucleus (168). Acute treatment with CRHR1 or CRHR2 agonists or with CRH failed to alter excitability of GnRH neurons in brain slices (170). Similarly, local application of CRH near the distal projections of GnRH neurons in the ventral arcuate did not affect intracellular Ca2+ concentrations in these projections (117). Despite the difficulties in confirming CRHR expression in or action directly on GnRH neurons, functional studies suggest that GnRH neurons are modulated by stress-induced changes, perhaps mediated via non-HPA stress pathways or intermediate neurons responsive to CRH or other stress mediators.

Corticosteroid action directly on GnRH neurons is possible as glucocorticoid receptors are expressed in these cells (171,172). Sustained cortisol treatment of ewes during an artificial follicular phase suppressed GnRH pulse frequency (104), which may indicate an indirect effect via arcuate kisspeptin (KNDy) or other pulse generating neurons (30,173). Blocking glucocorticoid receptors did not prevent the stress-induced suppression of GnRH pulse amplitude in ewes (174), however, again potentially suggesting indirect action.

10.2. Kisspeptin neurons

As mentioned in section 2, kisspeptin neurons in the arcuate nucleus (KNDy neurons) and AVPV are postulated to be major regulators of pulsatile and surge mode of GnRH release, respectively. Further, the steroid-sensitive nature of these neurons makes them a candidate site for integrating stress and steroid effects to modulate GnRH neuron output.

Both immunological and metabolic stresses have been shown decrease hypothalamic Kiss1 and Kiss1rexpression by 6h after stress exposure in male mice and female rats; these effects persisted for up to two days (106,175–177). Acute restraint stress did not change the number of Kiss1-expressing cells in the arcuate nucleus, but activation of arcuate kisspeptin neurons as measured by cFos expression was reduced after restraint stress in both male and female mice (178,179). A similar decrease in cFos expression in arcuate Kiss1-expressing cells was observed in OVX mice challenged with metabolic stress (180). The inhibitory effects of metabolic stress in the latter study did not affect kisspeptin-induced LH secretion in OVX mice, suggesting KNDy neurons are modulated by, and could be the direct targets of, metabolic stress to inhibit GnRH and subsequent LH output. The effect of stress on Kiss1 expression might be mediated through corticosterone and/or CRH, as administration of either substance had similar inhibitory effects on arcuate Kiss1 expression (106). AVPV kisspeptin neurons could also be a potential target for corticosterone as prolonged corticosterone treatment inhibits Kiss1 expression and neuronal activation of AVPV kisspeptin neurons in OVX+E mice during positive feedback (95).

Ascribing these effects to direct action on kisspeptin neurons is tempting but somewhat tenuous for at least two reasons: controversy over expression of appropriate receptors by these cells and the difference in time course of the suppression of LH pulses vs the immunohistochemical measures. With regard to receptors for HPA axis hormones, immunoreactive glucocorticoid receptors have been reported in arcuate kisspeptin neurons of both OVX and OVX+E mice (109), but another study identified these receptors in only AVPV kisspeptin neurons (181). As with GnRH neurons, expression of CRHRs by kisspeptin neurons is unresolved. One immunofluorescence study in diestrous female rats reported that both AVPV and arcuate kisspeptin neurons express CRHR (subtype not identified) (181). Another study using CRHR1 reporter mice indicated expression of CRHR1 in AVPV kisspeptin neurons (182), but the expression of CRHR in arcuate kisspeptin neurons awaits confirmation. Retrograde viral tracing specifically from arcuate kisspeptin neurons failed to identify CRH neurons in the PVN as afferents (183), but that does not preclude other CRH populations from projecting to these cells. It is also important to point out that other central elements that are involved in receiving and responding to different stressors may well affect the reproductive neuroendocrine system through arcuate and/or AVPV kisspeptin neurons.

With regard to the timing of changes in LH pulses vs the immunochemical measures, the firing activity of arcuate kisspeptin neurons in brain slices was not acutely altered by CRH in brain slices from OVX or OVX+E mice prepared in models of either negative or positive estradiol feedback (117,170). Similarly optogenetic activation of PVN CRH neurons in brain slices diestrous female mice failed to alter firing rate of arcuate kisspeptin neurons (117,170). Interestingly, in vivo activation of PVN CRH neurons with chemogenetics did briefly reduce LH pulse frequency in OVX mice but this effect was somewhat delayed with one or two LH pulses occurring between administration of clozapine n-oxide and the eventual suppression (117). In contrast, suppression of LH pulses by stress was essentially immediate (153,180). Together these findings could be interpreted to indicate that CRH from the PVN might not have an acute effect on the firing output of KNDy neurons, but this does not preclude possible longer-term effects of CRH or stress to change, for example, neuropeptide expression by this population to mediate longer-term effects of stress. Further studies are needed to determine if arcuate kisspeptin neurons receive direct inputs from CRH neurons, and if they respond to other systems activated by stress.

10.3. GABAergic signaling

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is one of the major regulators of GnRH neurons. In contrast to most neurons, GABA is typically an excitatory input to GnRH neurons due to the high intracellular concentration of Cl− in these cells (184,185). GABAergic inputs to GnRH neurons are modified by several factors including pubertal developmental, steroids, and metabolic status (186–189). Various stressors increased activity of GABAergic neurons detected by cFos expression in the medial preoptic area (mPOA) (190–192), where GnRH neurons reside, but whether or not these are direct afferents of GnRH neurons is not known. Pretreatment with GABAA or GABAB antagonists in the mPOA or arcuate nucleus prevented the inhibitory effect of restraint or immunological stress, and CRH treatment on LH pulse frequency (193,194). This indicates that GABAergic signaling is necessary for stress or CRH to alter LH secretion, but does not provide the cellular resolution to identify the cell types receiving this signaling. Moreover, administration of CRH to the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis or locus coeruleus increased neuronal activity measured by cFos expression in GAD67-identified GABAergic neurons in the mPOA (195,196). CRHR1 is expressed in a small portion of GABAergic neurons in mPOA located near GnRH neurons (169). This provides possible link between CRH and/or stress-induced GABAergic signaling to GnRH neurons. The frequency of GABAergic postsynaptic currents in GnRH neurons in brain slices was increased by bath application of a CRHR1, but not CRHR2 agonist (170). As with effects of these receptor-specific agonists on GnRH neuron firing rate (155), this effect was limited to GnRH neurons from OVX+E mice (170). Hypothalamic GABAergic neurons express ERα (197) and therefore could be influenced by estradiol. Estradiol induces time-of-day shifts in GABA transmission to GnRH neurons (188) and modulates synaptic plasticity in several brain regions, including the hypothalamus (198–200). Because of the excitatory effects of GABA on GnRH neurons, the observation that CRHR1 agonists increase both firing rate of and GABA transmission to GnRH neurons suggests that one possible stimulatory mechanism for CRH on GnRH neurons may be via activation of GABAergic neurons.

10.4. RFamide-related peptide-3 (RFRP-3)

The discovery of an inhibitory regulator of GnRH neurons in 2000 by Tsutsui and colleagues identified another pathway involved in regulating the HPG axis (201). RFRP-3 was first discovered in birds and named gonadotropin-inhibitory hormone, or GnIH, based on its physiological function. In mammals, it is known as RFamide-related peptide-3 (RFRP-3), because it shares a structure of LPXRFamide (where X is L or Q), RFRP-3 neurons of the dorsomedial hypothalamic area project to GnRH neurons and RFRP-3 inhibits activity of GnRH neurons (202,203). In addition to possible direct action at GnRH cell bodies, RFRP-3 neurons also project to the median eminence. RFRP-3 generally inhibits gonadotropin secretion from the pituitary (204–206) but can exhibit stimulatory effects on gonadotropin secretion in some conditions (207,208). RFRP-3 neurons express ERα and androgen receptors in female and male hamsters, respectively (203), thus can respond directly to sex steroids and their likely effects to modify the response to stress.

RFRP-3 was shown to be a possible link between the HPA and HPG axes. The first evidence that supported this hypothesis was that RFRP-3 expression is increased by stress in sparrows (209). Later, acute and chronic immobilization stress were shown to upregulate RFRP-3 expression in male rats (210). Stress might act on RFRP-3 neurons via both CRH and corticosterone due to the presence of both CRHR1 or glucocorticoid receptors in about 13% and 53% in RFRP-3 neurons from male rats (210). In these studies, RFRP-3 expression was negatively correlated to plasma LH concentration. Stress also increases cFos expression in RFRP-3 neurons in male and female mice and in ewes (178,179,211). Knockdown of RFRP-3 in female mice during stress induction diminished the adverse effects of restraint stress on pregnancy outcome (212). Moreover, a recent study demonstrated restraint stress failed to suppress LH pulses in RFRP-3-ablated female mice (213). Together, these data support the hypothesis that RFRP-3 mediates, at least in part, stress-induced inhibition of LH release. It is important to note that metabolic stress did not affect RFRP-3 expression or activation of RFRP-3 neurons (214). Therefore, RFRP-3 might mediate some but not all inhibitory effect of stress on the HPG axis. However, physiological studies on the mechanisms of stress and RFRP-3 are still needed.

11. Conclusions and future directions

Normal operation of the HPG axis is important to maintain fertility. This review has highlighted how the effects of hormones of the HPA axis and their roles in the stress response and affect the activity of the HPG axis. Several studies strongly suggest that CRH signaling mediates some of the effects of stress on the reproductive system, and that this effect can be acutely stimulatory. In addition to CRH, glucocorticoids are also involved in the interactions between these axes (Figure 1). Several questions still remain unsolved, however.

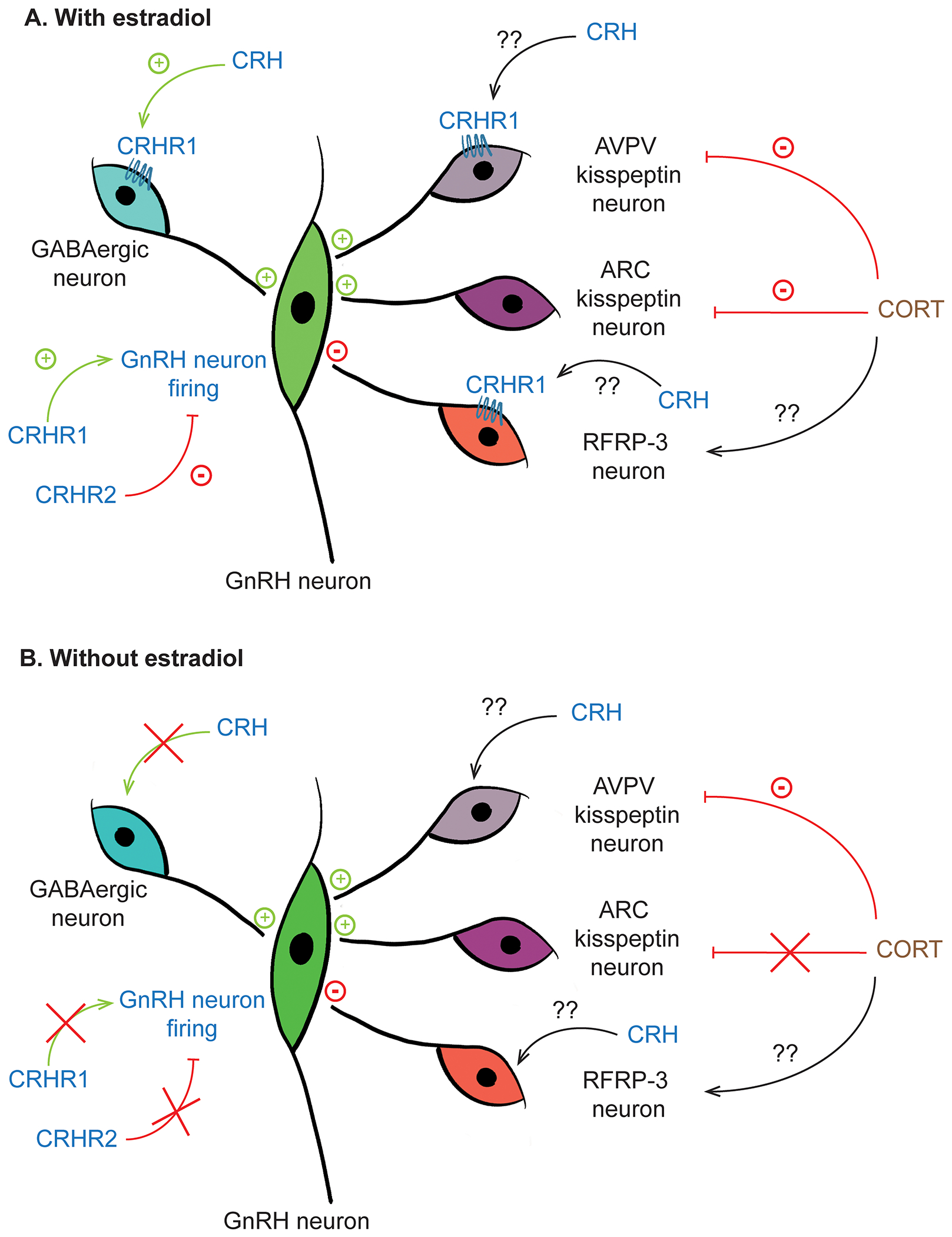

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of how components of HPA axis act on central components of HPG axis. A) In the presence of estradiol, activation of CRHR1 increases GABAergic inputs to GnRH neurons and increases firing activity of GnRH neurons. Corticosterone appears to suppress activity of kisspeptin neurons both in the AVPV and ARC populations. B) In the absence of estradiol, effects of CRH and corticosterone on the HPG axis are markedly diminished.

First, the expression of CRHR1 and CRHR2 in cells regulating the HPG axis remains controversial. The available data show both presence and absence of CRHR in GnRH neurons that is dependent on sex, species, and detection methods. If GnRH neurons lack CRHR, do upstream regulators of GnRH neurons such as kisspeptin neurons (arcuate and AVPV populations), GABA and/or RFRP-3 neurons express CRHR and which subtype of CRHR do they express? Further, since sex steroids influence the stress response, and kisspeptin, GABA, CRH and RFRP-3 neurons all express steroid receptors, do sex steroids modulate expression of CRHRs in these neuronal populations, and if so, what are the active steroids and which populations are modified?

Central inhibitory effects of stress on GnRH/LH release can be mediated via CRHR2 activation. Which endogenous CRHR2 ligands (CRH and/or urocortin family members) are responsible for the inhibitory effects of stress? Another important question is which components in the HPG axis mediate inhibitory effect of stress? RFRP-3 is one potential intermediate between the HPA and HPG axes; this is a relatively recent observation that needs further study. How does stress affect the function of RFRP-3 neurons? Is this mediated by elements of the HPA axis or other mediators of the stress response? Is RFRP-3 involved in the inhibitory effects of stress on reproductive function? If so, does RFRP-3 signaling mediate the inhibitory effect of stress globally or are its actions limited to specific modalities, for example pulsatile vs surge secretion of GnRH/LH?

The information about stimulatory effect of stress on the HPG axis is very limited and has not been reported in a majority of the studies. This might be because the stimulatory effect of stress is acute and transient, and often followed by a subsequent prolong inhibitory effect that dominates the experimental time scale and thus the interpretation. Future experiments that study the time course of the response of the HPG axis to stress (e.g., LH secretion) in more detail are needed to test this hypothesis. Further, which components in the HPG axis are targets for stimulatory effect of stress, and which elements of the HPA axis are responsible for stimulatory actions are not completely understood. Ultimately, how do these stimulatory actions of stress affect fertility and reproductive outcomes?

The HPA axis is one of the pathways that are activated during stress response. During the physiological stress response, however, there are several factors that act on multiple levels and aspects of HPG axis. Therefore, understanding the interaction between HPA and HPG axis would provide a small piece of information to fill in the big picture of how stress interact with reproductive axis.

Highlights.

Stress typically inhibits reproductive parameters via components of the HPA axis

In certain conditions, stress can be stimulatory to reproductive system

Stress response is modulated by sex steroid hormones

Components of the HPA axis act at multiple targets in the HPG axis

Acknowledgements:

We thank Dr. Laura Burger and Megan Johnson for editorial comments. Supported by National Institute of Health/Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development R01 HD41469. CP was supported by the Anandamahidol Foundation, Thailand.

Abbreviations:

- CRHR

corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor

- GABA

gamma-aminobutyric acid

- RFRP-3

RFamide-related peptide-3 (aka GnIH, gonadotropin-inhibitory hormone)

- HPG

hypothalamo-pituitary-gonadal

- HPA

hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal

- MUA

multiunit electrical activity

- OVX

ovariectomized

- OVX+E

ovariectomized+estradiol

- PVN

paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reprint requests: should be addressed to corresponding author

Disclosure statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Silverman AJ, Livne I, Witkin JW. The Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), neuronal systems: immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridization. In: Knobil E, Neill JD, eds. The Physiology of Reproduction. Vol 1. 2 ed. New York: Raven Press; 1994:1683–1709. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarke IJ, Cummins JT. The temporal relationship between gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion in ovariectomized ewes. Endocrinology. 1982;111(5):1737–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson GL, Kuehl D, Rhim TJ. Testosterone inhibits gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse frequency in the male sheep. Biology of reproduction. 1991;45(1):188–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moenter SM, Caraty A, Locatelli A, Karsch FJ. Pattern of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretion leading up to ovulation in the ewe: existence of a preovulatory GnRH surge. Endocrinology. 1991;129(3):1175–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarkar DK, Chiappa SA, Fink G, Sherwood NM. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone surge in pro-oestrous rats. Nature. 1976;264(5585):461–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pau KY, Berria M, Hess DL, Spies HG. Preovulatory gonadotropin-releasing hormone surge in ovarian-intact rhesus macaques. Endocrinology. 1993;133(4):1650–1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xia L, Van Vugt D, Alston EJ, Luckhaus J, Ferin M. A surge of gonadotropin-releasing hormone accompanies the estradiol-induced gonadotropin surge in the rhesus monkey. Endocrinology. 1992;131(6):2812–2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schally AV, Arimura A, Kastin AJ, Matsuo H, Baba Y, Redding TW, Nair RM, Debeljuk L, White WF. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone: one polypeptide regulates secretion of luteinizing and follicle-stimulating hormones. Science. 1971;173(4001):1036–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haisenleder DJ, Dalkin AC, Ortolano GA, Marshall JC, Shupnik MA. A pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulus is required to increase transcription of the gonadotropin subunit genes: evidence for differential regulation of transcription by pulse frequency in vivo. Endocrinology. 1991;128(1):509–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wildt L, Hausler A, Marshall G, Hutchison JS, Plant TM, Belchetz PE, Knobil E. Frequency and amplitude of gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulation and gonadotropin secretion in the rhesus monkey. Endocrinology. 1981;109(2):376–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams TE, Norman RL, Spies HG. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor binding and pituitary responsiveness in estradiol-primed monkeys. Science. 1981;213(4514):1388–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christian CA, Mobley JL, Moenter SM. Diurnal and estradiol-dependent changes in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuron firing activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(43):15682–15687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karsch FJ, Cummins JT, Thomas GB, Clarke IJ. Steroid feedback inhibition of pulsatile secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone in the ewe. Biology of reproduction. 1987;36(5):1207–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leipheimer RE, Bona-Gallo A, Gallo RV. Influence of estradiol and progesterone on pulsatile LH secretion in 8-day ovariectomized rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1986;43(3):300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herbison AES MJ; Sim JA Erratum: Lack of detection of estrogen receptor-alpha transcripts in mouse gonadotropin releasing-hormone neurons. Endocrinology. 2001;142:493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hrabovszky E, Shughrue PJ, Merchenthaler I, Hajszan T, Carpenter CD, Liposits Z, Petersen SL. Detection of estrogen receptor-beta messenger ribonucleic acid and 125I-estrogen binding sites in luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons of the rat brain. Endocrinology. 2000;141(9):3506–3509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skynner MJ, Sim JA, Herbison AE. Detection of estrogen receptor alpha and beta messenger ribonucleic acids in adult gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Endocrinology. 1999;140(11):5195–5201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herbison AE, Skinner DC, Robinson JE, King IS. Androgen receptor-immunoreactive cells in ram hypothalamus: distribution and co-localization patterns with gonadotropin-releasing hormone, somatostatin and tyrosine hydroxylase. Neuroendocrinology. 1996;63(2):120–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hrabovszky E, Steinhauser A, Barabás K, Shughrue PJ, Petersen SL, Merchenthaler I, Liposits Z. Estrogen receptor-beta immunoreactivity in luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons of the rat brain. Endocrinology. 2001;142(7):3261–3264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oakley AE, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. Kisspeptin signaling in the brain. Endocr Rev. 2009;30(6):713–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang L, Vanacker C, Burger LL, Barnes T, Shah YM, Myers MG, Moenter SM. Genetic dissection of the different roles of hypothalamic kisspeptin neurons in regulating female reproduction. Elife. 2019;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cravo RM, Margatho LO, Osborne-Lawrence S, Donato J Jr., Atkin S, Bookout AL, Rovinsky S, Frazao R, Lee CE, Gautron L, Zigman JM, Elias CF. Characterization of Kiss1 neurons using transgenic mouse models. Neuroscience. 2011;173:37–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christian CA, Glidewell-Kenney C, Jameson JL, Moenter SM. Classical estrogen receptor alpha signaling mediates negative and positive feedback on gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuron firing. Endocrinology. 2008;149(11):5328–5334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jakacka M, Ito M, Martinson F, Ishikawa T, Lee EJ, Jameson JL. An estrogen receptor (ER)alpha deoxyribonucleic acid-binding domain knock-in mutation provides evidence for nonclassical ER pathway signaling in vivo. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16(10):2188–2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pielecka-Fortuna J, Chu Z, Moenter SM. Kisspeptin acts directly and indirectly to increase gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuron activity and its effects are modulated by estradiol. Endocrinology. 2008;149(4):1979–1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Messager S, Chatzidaki EE, Ma D, Hendrick AG, Zahn D, Dixon J, Thresher RR, Malinge I, Lomet D, Carlton MB, Colledge WH, Caraty A, Aparicio SA. Kisspeptin directly stimulates gonadotropin-releasing hormone release via G protein-coupled receptor 54. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(5):1761–1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han SK, Gottsch ML, Lee KJ, Popa SM, Smith JT, Jakawich SK, Clifton DK, Steiner RA, Herbison AE. Activation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons by kisspeptin as a neuroendocrine switch for the onset of puberty. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2005;25(49):11349–11356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gottsch ML, Cunningham MJ, Smith JT, Popa SM, Acohido BV, Crowley WF, Seminara S, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. A role for kisspeptins in the regulation of gonadotropin secretion in the mouse. Endocrinology. 2004;145(9):4073–4077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clarkson J, Herbison AE. Postnatal development of kisspeptin neurons in mouse hypothalamus; sexual dimorphism and projections to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Endocrinology. 2006;147(12):5817–5825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clarkson J, Han SY, Piet R, McLennan T, Kane GM, Ng J, Porteous RW, Kim JS, Colledge WH, Iremonger KJ, Herbison AE. Definition of the hypothalamic GnRH pulse generator in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E10216–E10223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Porteous R, Herbison AE. Genetic Deletion of Esr1 in the Mouse Preoptic Area Disrupts the LH Surge and Estrous Cyclicity. Endocrinology. 2019;160(8):1821–1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang L, Guo W, Shen X, Yeo S, Long H, Wang Z, Lyu Q, Herbison AE, Kuang Y. Different dendritic domains of the GnRH neuron underlie the pulse and surge modes of GnRH secretion in female mice. Elife. 2020;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang L, Moenter SM. Differential Roles of Hypothalamic AVPV and Arcuate Kisspeptin Neurons in Estradiol Feedback Regulation of Female Reproduction. Neuroendocrinology. 2020;110(3-4):172–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qiu J, Nestor CC, Zhang C, Padilla SL, Palmiter RD, Kelly MJ, Ronnekleiv OK. High-frequency stimulation-induced peptide release synchronizes arcuate kisspeptin neurons and excites GnRH neurons. Elife. 2016;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeFazio RA, Elias CF, Moenter SM. GABAergic transmission to kisspeptin neurons is differentially regulated by time of day and estradiol in female mice. J Neurosci. 2014;34(49):16296–16308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang L, Burger LL, Greenwald-Yarnell ML, Myers MG, Moenter SM. Glutamatergic Transmission to Hypothalamic Kisspeptin Neurons Is Differentially Regulated by Estradiol through Estrogen Receptor α in Adult Female Mice. J Neurosci. 2018;38(5):1061–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Selye H A syndrome produced by diverse nocuous agents. Nature. 1936;138(3479):32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szabo S, Tache Y, Somogyi A. The legacy of Hans Selye and the origins of stress research: a retrospective 75 years after his landmark brief “letter” to the editor# of nature. Stress. 2012;15(5):472–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Charmandari E, Tsigos C, Chrousos G. Endocrinology of the stress response. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:259–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ulrich-Lai YM, Herman JP. Neural regulation of endocrine and autonomic stress responses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(6):397–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spiess J, Rivier J, Rivier C, Vale W. Primary structure of corticotropin-releasing factor from ovine hypothalamus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1981;78(10):6517–6521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vale W, Spiess J, Rivier C, Rivier J. Characterization of a 41-residue ovine hypothalamic peptide that stimulates secretion of corticotropin and beta-endorphin. Science. 1981;213(4514):1394–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Battaglia DF, Brown ME, Krasa HB, Thrun LA, Viguie C, Karsch FJ. Systemic challenge with endotoxin stimulates corticotropin-releasing hormone and arginine vasopressin secretion into hypophyseal portal blood: coincidence with gonadotropin-releasing hormone suppression. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4175–4181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peng J, Long B, Yuan J, Peng X, Ni H, Li X, Gong H, Luo Q, Li A. A Quantitative Analysis of the Distribution of CRH Neurons in Whole Mouse Brain. Front Neuroanat. 2017;11:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith SM, Vale WW. The role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in neuroendocrine responses to stress. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8(4):383–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hu P, Liu J, Maita I, Kwok C, Gu E, Gergues MM, Kelada F, Phan M, Zhou JN, Swaab DF, Pang ZP, Lucassen PJ, Roepke TA, Samuels BA. Chronic Stress Induces Maladaptive Behaviors by Activating Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone Signaling in the Mouse Oval Bed Nucleus of the Stria Terminalis. J Neurosci. 2020;40(12):2519–2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Avery SN, Clauss JA, Blackford JU. The Human BNST: Functional Role in Anxiety and Addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(1):126–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Antoni FA. Vasopressinergic control of pituitary adrenocorticotropin secretion comes of age. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1993;14(2):76–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bourque CW, Oliet SH. Osmoreceptors in the central nervous system. Annu Rev Physiol. 1997;59:601–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carter DA, Lightman SL. Diurnal pattern of stress-evoked neurohypophyseal hormone secretion: sexual dimorphism in rats. Neurosci Lett. 1986;71(2):252–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rivier C, Vale W. Interaction of corticotropin-releasing factor and arginine vasopressin on adrenocorticotropin secretion in vivo. Endocrinology. 1983;113(3):939–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rivier C, Rivier J, Mormede P, Vale W. Studies of the nature of the interaction between vasopressin and corticotropin-releasing factor on adrenocorticotropin release in the rat. Endocrinology. 1984;115(3):882–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gallo-Payet N, Martinez A, Lacroix A. Editorial: ACTH Action in the Adrenal Cortex: From Molecular Biology to Pathophysiology. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2017;8:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Herman JP, McKlveen JM, Ghosal S, Kopp B, Wulsin A, Makinson R, Scheimann J, Myers B. Regulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenocortical Stress Response. Compr Physiol. 2016;6(2):603–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen R, Lewis KA, Perrin MH, Vale WW. Expression cloning of a human corticotropin-releasing-factor receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(19):8967–8971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Perrin M, Donaldson C, Chen R, Blount A, Berggren T, Bilezikjian L, Sawchenko P, Vale W. Identification of a second corticotropin-releasing factor receptor gene and characterization of a cDNA expressed in heart. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92(7):2969–2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lovenberg TW, Liaw CW, Grigoriadis DE, Clevenger W, Chalmers DT, De Souza EB, Oltersdorf T. Cloning and characterization of a functionally distinct corticotropin-releasing factor receptor subtype from rat brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92(3):836–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lovenberg TW, Chalmers DT, Liu C, De Souza EB. CRF2 alpha and CRF2 beta receptor mRNAs are differentially distributed between the rat central nervous system and peripheral tissues. Endocrinology. 1995;136(9):4139–4142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Potter E, Sutton S, Donaldson C, Chen R, Perrin M, Lewis K, Sawchenko PE, Vale W. Distribution of corticotropin-releasing factor receptor mRNA expression in the rat brain and pituitary. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91(19):8777–8781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chalmers DT, Lovenberg TW, De Souza EB. Localization of novel corticotropin-releasing factor receptor (CRF2) mRNA expression to specific subcortical nuclei in rat brain: comparison with CRF1 receptor mRNA expression. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1995;15(10):6340–6350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vaughan J, Donaldson C, Bittencourt J, Perrin MH, Lewis K, Sutton S, Chan R, Turnbull AV, Lovejoy D, Rivier C, et al. Urocortin, a mammalian neuropeptide related to fish urotensin I and to corticotropin-releasing factor. Nature. 1995;378(6554):287–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lewis K, Li C, Perrin MH, Blount A, Kunitake K, Donaldson C, Vaughan J, Reyes TM, Gulyas J, Fischer W, Bilezikjian L, Rivier J, Sawchenko PE, Vale WW. Identification of urocortin III, an additional member of the corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) family with high affinity for the CRF2 receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(13):7570–7575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reyes TM, Lewis K, Perrin MH, Kunitake KS, Vaughan J, Arias CA, Hogenesch JB, Gulyas J, Rivier J, Vale WW, Sawchenko PE. Urocortin II: a member of the corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) neuropeptide family that is selectively bound by type 2 CRF receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(5):2843–2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kageyama K Regulation of gonadotropins by corticotropin-releasing factor and urocortin. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2013;4:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jahn O, Tezval H, van Werven L, Eckart K, Spiess J. Three-amino acid motifs of urocortin II and III determine their CRF receptor subtype selectivity. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47(2):233–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cespedes IC, de Oliveira AR, da Silva JM, da Silva AV, Sita LV, Bittencourt JC. mRNA expression of corticotropin-releasing factor and urocortin 1 after restraint and foot shock together with alprazolam administration. Peptides. 2010;31(12):2200–2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weninger SC, Peters LL, Majzoub JA. Urocortin expression in the Edinger-Westphal nucleus is up-regulated by stress and corticotropin-releasing hormone deficiency. Endocrinology. 2000;141(1):256–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reyes TM, Lewis K, Perrin MH, Kunitake KS, Vaughan J, Arias CA, Hogenesch JB, Gulyas J, Rivier J, Vale WW, Sawchenko PE. Urocortin II: a member of the corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) neuropeptide family that is selectively bound by type 2 CRF receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2843–2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lewis K, Li C, Perrin MH, Blount A, Kunitake K, Donaldson C, Vaughan J, Reyes TM, Gulyas J, Fischer W, Bilezikjian L, Rivier J, Sawchenko PE, Vale WW. Identification of urocortin III, an additional member of the corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) family with high affinity for the CRF2 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7570–7575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li C, Vaughan J, Sawchenko PE, Vale WW. Urocortin III-immunoreactive projections in rat brain: partial overlap with sites of type 2 corticotrophin-releasing factor receptor expression. J Neurosci. 2002;22(3):991–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zorilla EP, Koob G. The roles of urocortins 1, 2, and 3 in the brain. In: Steckler T, Kalin NH, Reul JMHM, eds. Handbook of Stress and the Brain. Vol 15. New York: Elsevier Science; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Muglia L, Jacobson L, Dikkes P, Majzoub JA. Corticotropin-releasing hormone deficiency reveals major fetal but not adult glucocorticoid need. Nature. 1995;373(6513):427–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Smith GW, Aubry JM, Dellu F, Contarino A, Bilezikjian LM, Gold LH, Chen R, Marchuk Y, Hauser C, Bentley CA, Sawchenko PE, Koob GF, Vale W, Lee KF. Corticotropin releasing factor receptor 1-deficient mice display decreased anxiety, impaired stress response, and aberrant neuroendocrine development. Neuron. 1998;20(6):1093–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Timpl P, Spanagel R, Sillaber I, Kresse A, Reul JM, Stalla GK, Blanquet V, Steckler T, Holsboer F, Wurst W. Impaired stress response and reduced anxiety in mice lacking a functional corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1. Nat Genet. 1998;19(2):162–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vetter DE, Li C, Zhao L, Contarino A, Liberman MC, Smith GW, Marchuk Y, Koob GF, Heinemann SF, Vale W, Lee KF. Urocortin-deficient mice show hearing impairment and increased anxiety-like behavior. Nat Genet. 2002;31(4):363–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bale TL, Vale WW. CRF and CRF receptors: role in stress responsivity and other behaviors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:525–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bale TL, Contarino A, Smith GW, Chan R, Gold LH, Sawchenko PE, Koob GF, Vale WW, Lee KF. Mice deficient for corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor-2 display anxiety-like behaviour and are hypersensitive to stress. Nat Genet. 2000;24(4):410–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Coste SC, Kesterson RA, Heldwein KA, Stevens SL, Heard AD, Hollis JH, Murray SE, Hill JK, Pantely GA, Hohimer AR, Hatton DC, Phillips TJ, Finn DA, Low MJ, Rittenberg MB, Stenzel P, Stenzel-Poore MP. Abnormal adaptations to stress and impaired cardiovascular function in mice lacking corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor-2. Nat Genet. 2000;24(4):403–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jamieson PM, Li C, Kukura C, Vaughan J, Vale W. Urocortin 3 modulates the neuroendocrine stress response and is regulated in rat amygdala and hypothalamus by stress and glucocorticoids. Endocrinology. 2006;147(10):4578–4588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Donald RA, Redekopp C, Cameron V, Nicholls MG, Bolton J, Livesey J, Espiner EA, Rivier J, Vale W. The hormonal actions of corticotropin-releasing factor in sheep: effect of intravenous and intracerebroventricular injection. Endocrinology. 1983;113(3):866–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jamieson PM, Li C, Kukura C, Vaughan J, Vale W. Urocortin 3 modulates the neuroendocrine stress response and is regulated in rat amygdala and hypothalamus by stress and glucocorticoids. Endocrinology. 2006;147:4578–4588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bethea CL, Centeno ML, Cameron JL. Neurobiology of stress-induced reproductive dysfunction in female macaques. Mol Neurobiol. 2008;38(3):199–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rivier C, Rivier J, Vale W. Stress-induced inhibition of reproductive functions: role of endogenous corticotropin-releasing factor. Science. 1986;231(4738):607–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wagenmaker ER, Breen KM, Oakley AE, Tilbrook AJ, Karsch FJ. Psychosocial stress inhibits amplitude of gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulses independent of cortisol action on the type II glucocorticoid receptor. Endocrinology. 2009;150(2):762–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Saketos M, Sharma N, Santoro NF. Suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis in normal women by glucocorticoids. Biology of reproduction. 1993;49(6):1270–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.McCosh RB, Breen KM, Kauffman AS. Neural and endocrine mechanisms underlying stress-induced suppression of pulsatile LH secretion. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2019;498:110579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Breen KM, Karsch FJ. New insights regarding glucocorticoids, stress and gonadotropin suppression. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2006;27(2):233–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Karsch FJ, Battaglia DF, Breen KM, Debus N, Harris TG. Mechanisms for ovarian cycle disruption by immune/inflammatory stress. Stress. 2002;5:101–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hernandez-Arteaga E, Hernandez-Gonzalez M, Renteria MLR, Almanza-Sepulveda ML, Guevara MA, Silva MA, Jaime HB. Prenatal stress alters the developmental pattern of behavioral indices of sexual maturation and copulation in male rats. Physiol Behav. 2016;163:251–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cowan CSM, Richardson R. Early-life stress leads to sex-dependent changes in pubertal timing in rats that are reversed by a probiotic formulation. Dev Psychobiol. 2019;61(5):679–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Knox AM, Li XF, Kinsey-Jones JS, Wilkinson ES, Wu XQ, Cheng YS, Milligan SR, Lightman SL, O’Byrne KT. Neonatal lipopolysaccharide exposure delays puberty and alters hypothalamic Kiss1 and Kiss1r mRNA expression in the female rat. Journal of neuroendocrinology. 2009;21(8):683–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Li XF, Adekunbi DA, Alobaid HM, Li S, Pilot M, Lightman SL, O’Byrne KT. Role of the posterodorsal medial amygdala in predator odour stress-induced puberty delay in female rats. Journal of neuroendocrinology. 2019;31(6):e12719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Manzano Nieves G, Schilit Nitenson A, Lee HI, Gallo M, Aguilar Z, Johnsen A, Bravo M, Bath KG. Early Life Stress Delays Sexual Maturation in Female Mice. Front Mol Neurosci. 2019;12:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Breen KM, Thackray VG, Hsu T, Mak-McCully RA, Coss D, Mellon PL. Stress levels of glucocorticoids inhibit LHbeta-subunit gene expression in gonadotrope cells. Molecular endocrinology. 2012;26(10):1716–1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Luo E, Stephens SB, Chaing S, Munaganuru N, Kauffman AS, Breen KM. Corticosterone Blocks Ovarian Cyclicity and the LH Surge via Decreased Kisspeptin Neuron Activation in Female Mice. Endocrinology. 2016;157(3):1187–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Xiao E, Xia-Zhang L, Barth A, Zhu J, Ferin M. Stress and the menstrual cycle: relevance of cycle quality in the short- and long-term response to a 5-day endotoxin challenge during the follicular phase in the rhesus monkey. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1998;83(7):2454–2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Xiao E, Xia-Zhang L, Ferin M. Inadequate luteal function is the initial clinical cyclic defect in a 12-day stress model that includes a psychogenic component in the Rhesus monkey. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2002;87(5):2232–2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pollard I, White BM, Bassett JR, Cairncross KD. Plasma glucocorticoid elevation and desynchronization of the estrous cycle following unpredictable stress in the rat. Behav Biol. 1975;14(01):103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Karsch FJ, Battaglia DF, Breen KM, Debus N, Harris TG. Mechanisms for ovarian cycle disruption by immune/inflammatory stress. Stress. 2002;5(2):101–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Debus N, Breen KM, Barrell GK, Billings HJ, Brown M, Young EA, Karsch FJ. Does cortisol mediate endotoxin-induced inhibition of pulsatile luteinizing hormone and gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion? Endocrinology. 2002;143(10):3748–3758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Breen KM, Karsch FJ. Does cortisol inhibit pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion at the hypothalamic or pituitary level? Endocrinology. 2004;145(2):692–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Breen KM, Stackpole CA, Clarke IJ, Pytiak AV, Tilbrook AJ, Wagenmaker ER, Young EA, Karsch FJ. Does the type II glucocorticoid receptor mediate cortisol-induced suppression in pituitary responsiveness to gonadotropin-releasing hormone? Endocrinology. 2004;145(6):2739–2746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Breen KM, Billings HJ, Wagenmaker ER, Wessinger EW, Karsch FJ. Endocrine basis for disruptive effects of cortisol on preovulatory events. Endocrinology. 2005;146(4):2107–2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Oakley AE, Breen KM, Clarke IJ, Karsch FJ, Wagenmaker ER, Tilbrook AJ. Cortisol reduces gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse frequency in follicular phase ewes: influence of ovarian steroids. Endocrinology. 2009;150(1):341–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Oakley AE, Breen KM, Tilbrook AJ, Wagenmaker ER, Karsch FJ. Role of estradiol in cortisol-induced reduction of luteinizing hormone pulse frequency. Endocrinology. 2009;150(6):2775–2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kinsey-Jones JS, Li XF, Knox AM, Wilkinson ES, Zhu XL, Chaudhary AA, Milligan SR, Lightman SL, O’Byrne KT. Down-regulation of hypothalamic kisspeptin and its receptor, Kiss1r, mRNA expression is associated with stress-induced suppression of luteinising hormone secretion in the female rat. Journal of neuroendocrinology. 2009;21(1):20–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Li XF, Mitchell JC, Wood S, Coen CW, Lightman SL, O’Byrne KT. The effect of oestradiol and progesterone on hypoglycaemic stress-induced suppression of pulsatile luteinizing hormone release and on corticotropin-releasing hormone mRNA expression in the rat. Journal of neuroendocrinology. 2003;15(5):468–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gore AC, Attardi B, DeFranco DB. Glucocorticoid repression of the reproductive axis: effects on GnRH and gonadotropin subunit mRNA levels. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;256(1-2):40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kreisman M, McCosh R, Tian K, Song C, Breen K. Estradiol enables chronic corticosterone to inhibit pulsatile LH secretion and suppress Kiss1 neuronal activation in female mice. Neuroendocrinology. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]