Abstract

Objective

RNA helicase DDX5 is downregulated during HBV replication and poor prognosis HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The objective of this study is to investigate the role of DDX5 in interferon (IFN) signalling. We provide evidence of a novel mechanism involving DDX5 that enables translation of transcription factor STAT1 mediating the IFN response.

Design and results

Molecular, pharmacological and biophysical assays were used together with cellular models of HBV replication, HCC cell lines and liver tumours. We demonstrate that DDX5 regulates STAT1 mRNA translation by resolving a G-quadruplex (rG4) RNA structure, proximal to the 5′ end of STAT1 5′UTR. We employed luciferase reporter assays comparing wild type (WT) versus mutant rG4 sequence, rG4-stabilising compounds, CRISPR/Cas9 editing of the STAT1-rG4 sequence and circular dichroism determination of the rG4 structure. STAT1-rG4 edited cell lines were resistant to the effect of rG4-stabilising compounds in response to IFN-α, while HCC cell lines expressing low DDX5 exhibited reduced IFN response. Ribonucleoprotein and electrophoretic mobility assays demonstrated direct and selective binding of RNA helicase-active DDX5 to the WT STAT1-rG4 sequence. Immunohistochemistry of normal liver and liver tumours demonstrated that absence of DDX5 corresponded to absence of STAT1. Significantly, knockdown of DDX5 in HBV infected HepaRG cells reduced the anti-viral effect of IFN-α.

Conclusion

RNA helicase DDX5 resolves a G-quadruplex structure in 5′UTR of STAT1 mRNA, enabling STAT1 translation. We propose that DDX5 is a key regulator of the dynamic range of IFN response during innate immunity and adjuvant IFN-α therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Interferon (IFN) type I/III signalling acting through the JAK/STAT pathway exerts antiviral, antitumour and immunomodulatory effects.1 2 Effects of IFN-α and IFN-β are mediated by tyrosine phosphorylation of transcription factors STAT1 and STAT2, followed by formation of ISGF3 complex via interaction with IRF9, translocation to the nucleus and transcriptional induction of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs). In addition to tyrosine phosphorylation, STAT1 activity is further modulated by modifications including methylation,3 acetylation4 and ubiquitination.5 Since STAT1 is involved in all types (I/III) of IFN signalling,6 these post-translational modifications influence all types (I/III) of IFN signalling, depending on cellular context. Herein, we provide evidence for a novel mechanism of STAT1 regulation, involving translational control of STAT1 mRNA, studied in the HBV replicating HepAD38 cell line7 and HBV infection model of differentiated HepaRG cells.8

HBV infection is a significant global health problem with more than 250 million chronically infected patients. Chronic HBV infection is associated with progressive liver disease, cirrhosis and development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Curative treatments for early stage HCC include liver resection, transplantation or local ablation. In advanced stage HCC, multikinase inhibitors9–11 offer only palliative benefits. In addition, because IFNs exert both antiviral and antiproliferative effects,12 13 adjuvant IFN-α therapy has been extensively applied for treatment of chronically HBV-infected patients with HCC. Unfortunately, many patients do not respond to IFN-α.14 Importantly, HCC patients with increased expression of the ISG IFIT3, a direct transcription target of STAT1,15 predict positive response to IFN-α therapy,16 suggesting IFN-α non-responders lack STAT1 activation and/or expression.

Viruses have evolved effective strategies to hijack cellular pathways for their growth advantage, including mechanisms for immune evasion. In our studies, we have identified a cellular mechanism hijacked by HBV associated with both viral biosynthesis and poor prognosis HBV-related HCC.17–19 This mechanism involves the chromatin modifying PRC2 complex and RNA helicase DDX5. PRC2 mediates repressive histone modifications (H3K27me3),20 while RNA helicase DDX5 is involved in transcription, epigenetic regulation, miRNA processing, mRNA splicing, decay and translation.21 22 Interestingly, HBV infection downregulates DDX5 via induction of two microRNA clusters23: miR17 ~92 and miR106 ~25.17–19 Moreover, HBV replicating cells with reduced DDX5 exhibit Wnt activation, resistance to chemotherapeutic agents23 and reduced protein levels of STAT1, as we describe herein.

In this study, we provide evidence that DDX5 is involved in a novel mechanism of translational control of STAT1, a transcription factor mediating all types (I/III) of IFN signalling. Specifically, RNA helicase DDX5 resolves a secondary RNA structure called G-quadruplex,24 located in the 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR) of STAT1 mRNA, thereby enabling its translation. G-quadruplexes are four-stranded structures formed in guanine (G)-rich sequences,25 and when located in 5′UTRs of mRNAs, influence post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression.20 One of the first examples of translational repression by an RNA G-quadruplex (rG4) was demonstrated for human NRAS mRNA.26 Bioinformatics analysis estimated nearly 3000 5′UTR rG4s in the human genome,26 and rG4 sequencing of polyA+HeLa RNA generated a global map of thousands rG4 structures.27 Recently, it was discovered that DDX5 proficiently resolves both RNA and DNA G4 structures.28

The significance of this mechanism of translational control of STAT1 is dependence on the protein level and activity of the rG4-resolving helicase. Our results presented herein demonstrate that the IFN response is influenced by this dynamic mechanism of STAT1 translational regulation, dependent on the protein level of DDX5.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Human HCC cell lines HepG2, Huh7, Snu387, Snu423, HepaRG,29 HepAD38,7 CLC15 and CLC4630 were grown as described and regularly tested for mycoplasma using PCR Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Abm). HepAD38 cells support HBV replication by tetracycline removal.7 HepAD38 were STR tested by ATCC. Human A549 and Panc-1 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with 10% FBS. Stable HepaRG cell lines were constructed expressing DDX5-FLAG-WT, and site directed DDX5-FLAG mutants K144N and D248N described previously,18 using the doxycycline inducible vector PLVX-puro (online supplemental table S1).

Transfection assays

HepAD38, Huh7 and HepaRG cells (0.3×106 cells per well of six-well plate) were transfected with control (Ctrl) or DDX5 siRNAs (40 nM). Following transfection (48 hours), cells were harvested for RNA or protein extraction and analysed by qRT-PCR or immunoblotting, respectively. HepAD38, Huh7 and HepaRG cells (0.1×106 cells per well of 12-well plate) were cotransfected with Renilla luciferase (25 ng) and WT STAT1-5′UTR-Luciferase (pFL-SV40-STAT1-5′UTR a gift from Dr Ming-Chih Lai) (50 ng) or mutant MT-STAT1-5′UTR-Luciferase (50 ng) using Lipofectamine 3000 (Life Technologies). In HepAD38 cells, HBV replication was induced by tetracycline removal 4 days prior to transfection with Renilla and Firefly luciferase vectors. Ctrl or DDX5 siRNAs (40 nM each) were cotransfected with Renilla and Firefly luciferase vectors using RNAiMax (Life Technologies). Plasmids used are listed in online supplemental table S1. Firefly luciferase activity was measured 24 hours after transfection using Dual Luciferase Assay system (Promega) according to manufacturer’s protocol, normalised to Renilla luciferase.

HBV infection assays

HepaRG cells plated in 24-well plates were subjected to DMSO-induced differentiation for 1 month.31 Differentiated dHepaRG cells were infected with HBV at multiplicity of infection=500, in the presence of 4% Peg8000. One day postinfection, cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline and maintained in culture until establishment of infection, that is, stable cccDNA level at 5–7 days. siRNAs (25 nM) were transfected on day 8 postinfection (p.i.) with lipofectamine RNAimax, according to supplier’s recommendations. IFNα treatments were performed, starting on day 11 p.i., every 3 days. Cells were harvested on day 17 p.i., to quantify viraemia (qPCR) and viral RNAs by RT-qPCR.

Immunoblot and immunohistochemistry assays performed as described.18 Densitometric analysis of immunoblots was by ImageJ. Antibodies used are listed in online supplemental table S2).

RNA preparation and qRT-PCR assay

RNA preparation and qRT-PCR performed according to manufacturer’s instructions, employing commercially available kits (online supplemental table S4). Primer sequences listed in online supplemental table S3.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy of RNA oligonucleotides performed as described,32 employing Jasco J-1100 spectropolarimeter equipped with thermoelectrically controlled cell holder. CD measurements were performed using quartz cell with optical path length of 1 mm. Blank sample contained only buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4). Each CD spectroscopy measurement was the average of two scans, collected between 340 and 200 nm at 25°C, scanning speed 50 nm/min. CD melting experiments were performed at 264 nm with heating rate of 2 °C/min between 25°C and 95°C. RNA sample concentration was 10 μM.

CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing

Huh7 and HepaRG cells were used to introduce indels targeting essential nucleotides of the G-quadruplex structure in 5′UTR region of STAT1 gene.33 Ribonucleoprotein of Cas9–2NLS (10 pmol) and guide RNA (50 pmol, Synthego) were loaded onto a 10 μL Neon Tip and electroporated into 1×105 Huh7 and HepaRG cells, using Neon Transfection System at 1200 V, for 20 ms and four pulses (ThermoFisher Scientific), according to manufacturer’s instructions. Genomic DNA was isolated and used for rapid PAGE genotyping34 to validate incorporation of indels, 48 hours after electroporation. Validated pools of cells were subjected to clonal selection. Isolated single colonies were confirmed by rapid PAGE genotyping and allelic sequencing.

RIP immunoprecipitation (RIP) assay

RIP assays employed the Magna RIP RNA-Binding Protein Immunoprecipitation Kit (Millipore Sigma) following manufacturer’s instructions. Antibodies and primer sequences used are listed in online supplemental tables S2 and S3, respectively.

RNA pull-down assay

RNA folding and pull-down assays were performed as described with modifications.35 Briefly, synthetic 5′-biotinylated rG4 (Bio-rG4) wild type (WT) or mutant (MT) RNA oligonucleotides (Millipore Sigma) were diluted to 5 mM in folding buffer, heated to 95°C and cooled to 25°C. G-quadruplex formation determined by circular dichroism (CD). Whole cell extracts from HepAD38, Huh7 and HepaRG cells were incubated with folded biotinylated RNAs (online supplemental table S3), followed by pull down with streptavidin beads (Promega). Bound proteins analysed by immunoblotting.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

DDX5-FLAG-WT, DDX5-FLAG-K144N and DDX5-FLAG-D248N proteins were purified from lysates of respective HepaRG cell lines following doxycycline induction (48 hours), using Anti-FLAG M2 Magnetic Beads (Millipore Sigma) per manufacturer’s instructions. Synthetic Bio-rG4 (500 nM) WT or MT RNA oligonucleotides (Millipore Sigma) were processed to form G-quadruplex as described and incubated with increasing amount (1–100 ng/μL) of DDX5 protein in reactions containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 9.0, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT and 100 μg/mL BSA on ice for 15 min. Binding reactions were adjusted to 5% (v/v) with glycerol and analysed by electrophoresis on a 1.5% native agarose minigel in cold 0.5X Tris-Borate-EDTA buffer, pH 9.0. RNA oligonucleotides were stained by SYBR-Gold dye (ThermoFisher) and visualised by ChemiDoc Touch Imaging System.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired t-test in GraphPad Prism V.6.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA). Differences were considered significant when p<0.05.

RESULTS

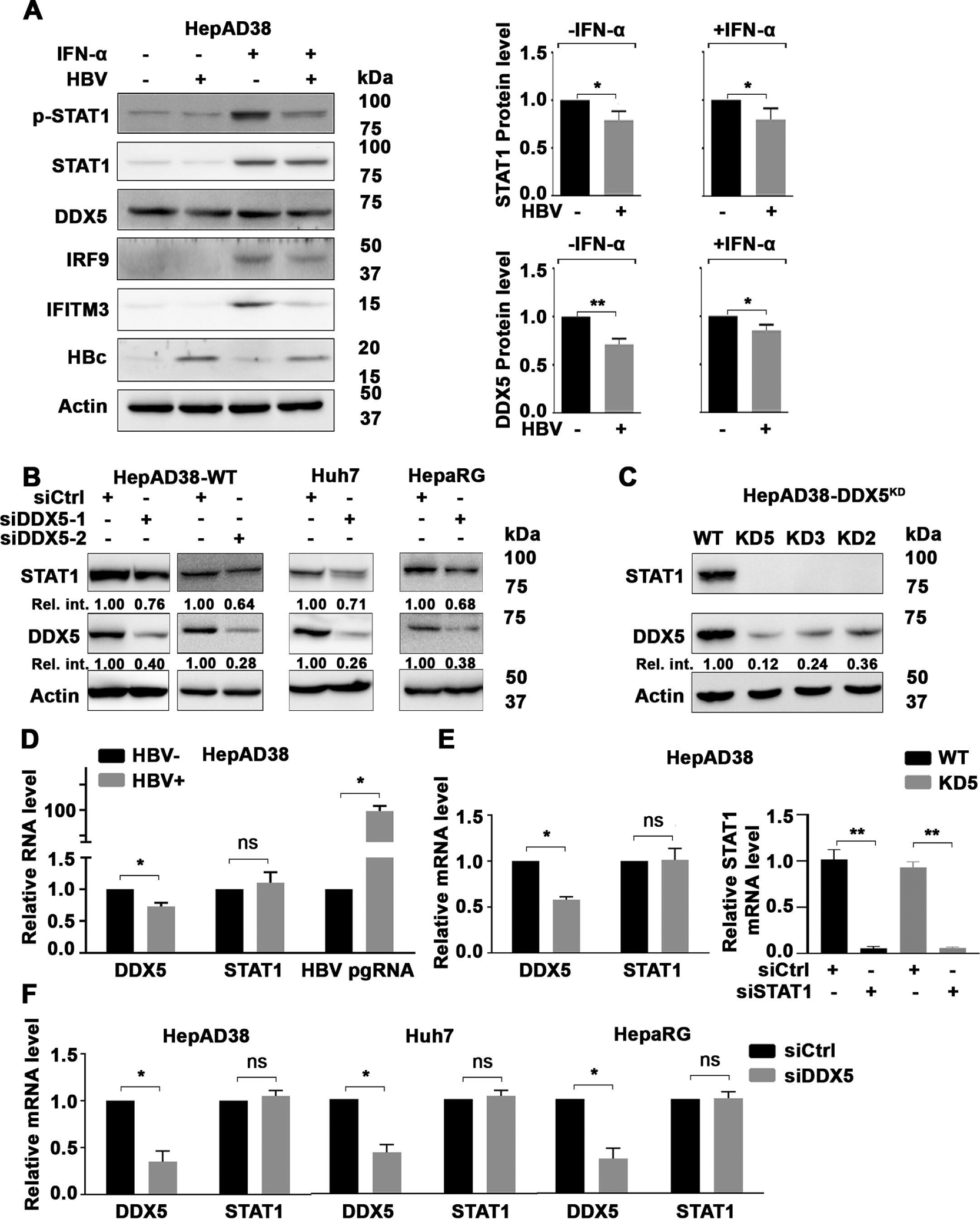

We examined various liver cancer cell lines, HepG2, Huh7, Snu423 and HepaRG for IFN-α response, employing immunoblots for activated phospho-STAT1 (T701) and expression of ISG IRF9. All cell lines responded to IFN-α, including the HBV replicating HepAD38 cell line that contains a stably integrated copy of the HBV genome under control of the Tet-off promoter7 (figure 1A, online supplemental figure S1A,B–C). In the absence of IFN-α treatment, HBV replication in HepAD38 cells exerted a small but reproducible reduction on STAT1 protein level (figure 1A). Following IFN-α treatment for 24 hours, levels of STAT1, p-STAT1 and downstream ISGs IRF9 and IFITM3 were similarly reduced (figure 1A). Likewise, HBV replication exerted a reproducible decrease in protein level of DDX5, irrespective of IFN-α treatment (figure 1A), as reported previously.18

Figure 1.

DDX5 knockdown regulates STAT1 mRNA translation. (A) Immunoblots of IFN-α induced proteins using lysates from HepAD38 cells with (+) or without (−) HBV replication for 5 days as a function of IFN-α (500 ng/mL) treatment for the last 24 hours. (Right panel) Quantification of DDX5 and STAT1 protein level, by ImageJ software, from three independent biological replicates. *P<0.05, **p<0.01; error bars indicate mean±SEM. Immunoblot of indicated proteins in: (B) HepAD38, Huh7 and HepaRG cells transfected with DDX5 siRNAs (siDDX5-1 or siDDX5-2) or negative control siRNA (siCtrl) for 48 hours and (C) in WT and DDX5 knockdown (DDX5KD) HepAD38 cell lines KD2, KD3 and KD5. (D–F) qRT-PCR of HBV pgRNA and STAT1 mRNA, as indicated, using RNA from: (D) HepAD38 cells with (+) or without (−) HBV replication for 5 days; (E) WT and KD5 HepAD38 cells (left panel), and WT and KD5 HepAD38 cells transfected with siSTAT1 or siCtrl for 48 hours (right panel); and (F) HepAD38, Huh7 and HepaRG cells transfected with siDDX5 or siCtrl for 48 hours. Statistical analysis of DDX5 and STAT1 mRNA levels from three biological replicates. *P<0.05. Error bars indicate mean±SEM. IFN, interferon; NS, not significant.

To determine whether DDX5 downregulation was associated with downregulation of STAT1 observed during HBV replication (figure 1A), we transfected siRNA for DDX5 in HepAD38 cells. Surprisingly, reduction in DDX5 protein resulted in reduction in STAT1 protein level (figure 1B). DDX5 knockdown in Huh7 and HepaRG cell lines also resulted in reduced STAT1 protein (figure 1B), whose t1/2 was quantified to be 16 hours (online supplemental figure S2A,B). Next, we examined STAT1 protein levels in three clonal DDX5-knockdown (DDX5KD) cell lines, KD2, KD3 and KD5, constructed in HepAD38 cells.23 These cell lines lacked STAT1 protein (figure 1C) and IFN-α response (online supplemental figure S2C). Interestingly, STAT1 mRNA levels were unaffected in HBV replicating HepAD38 cells (figure 1D), in DDX5KD HepAD38 cells (figure 1E) and on transient siRNA-mediated DDX5 knockdown in HepAD38, Huh7 and HepaRG cells (figure 1F), thereby excluding DDX5 effects on STAT1 transcription. By contrast, transfection of STAT1 siRNA abolished STAT1 mRNA detected by qRT PCR, in both WT and DDX5KD HepAD38 cells (figure 1E).

The STAT1 gene contains 24 introns. Accordingly, we examined whether intron detention or aberrant splicing are regulated by DDX5. qRT-PCR and RNA-seq intron data analyses of STAT1 in WT HepAD38 cells versus DDX5-knockdown cells excluded STAT1 intron detention (online supplemental figure S3A). Likewise, comparison of STAT1 mRNA sequence from WT versus DDX5KD cells, excluded aberrant splicing involving the mRNA splice site in proximity to AUG (online supplemental figure S3B). These results suggested DDX5 regulates STAT1 mRNA translation.

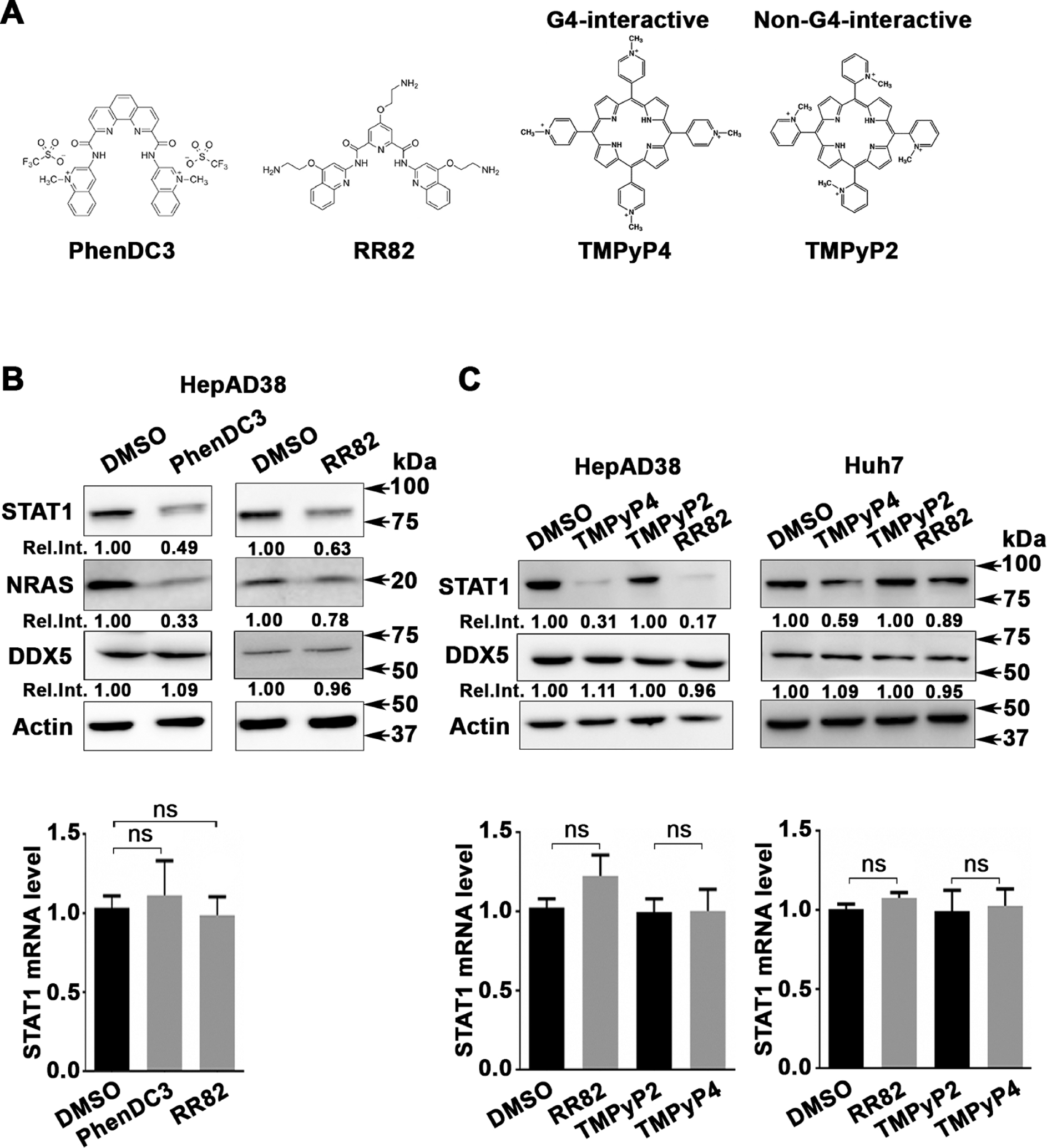

rG4 structures in 5’UTR of human STAT1 mRNA

Having excluded DDX5 effects on STAT1 mRNA transcription and processing, we reasoned, the information for post-transcriptional regulation must be located in the sequence or structure of STAT1 5′UTR. Surprisingly, the rG4-seq transcriptomic studies by Kwok et al27 identified the 5′UTR of human STAT1 mRNA as a high probability mRNA harbouring rG4 structures (online supplemental figure S3C). To test this hypothesis, and using NRAS as our positive control,26 we examined the effect of several G4 stabilising compounds (figure 2A), including PhenDC3 and RR82,24 on STAT1 protein level. Both compounds reduced STAT1 and NRAS protein level, without affecting DDX5 protein levels (figure 2A) or STAT1 mRNA (figure 2B). Similarly, we tested the effect of the G4-interactive TMPyP4 and its corresponding non-G4-interactive TMPyP2 compound36 on STAT1 protein and mRNA levels, using HepAD38 and Huh7 cells (figure 2C). The G4-interactive TMPyP4, similar to RR82, suppressed STAT1 protein levels, whereas the non-G4 interactive TMPyP2 exerted no effect. Importantly, these compounds did not affect DDX5 protein or STAT1 mRNA levels (figure 2C). We interpret these results to mean the 5′UTR of STAT1 contains a putative rG4 structure, regulating STAT1 expression post-transcriptionally.

Figure 2.

G-quadruplex-stabilising drugs reduce STAT1 protein levels. (A) Chemical structure of G4-stabilising compounds PhenDC3, RR82, TMPyP4 and TMPyP2. (B) Immunoblots of STAT1, NRAS and DDX5, using lysates from HepAD38 cells treated for 48 hours with PhenDC3 (5 μM) or RR82 (5 μM). (Lower panel) qRT-PCR of STAT1 mRNA using RNA from HepAD38 cells treated with DMSO, PhenDC3 (5 μM) or RR82 (5 μM) for 48 hours. (C) Immunoblots of STAT1 from lysates of HepAD38 and Huh7 cells treated with TMPyP4 (5 μM) or TMPyP2 (5 μM) for 48 hours. (Lower panel) qRT-PCR of STAT1 mRNA from HepAD38 and Huh7 cells, treated as indicated. Statistical analysis of STAT1 mRNA is from three biological replicates. Error bars indicate mean±SEM. NS, not significant.

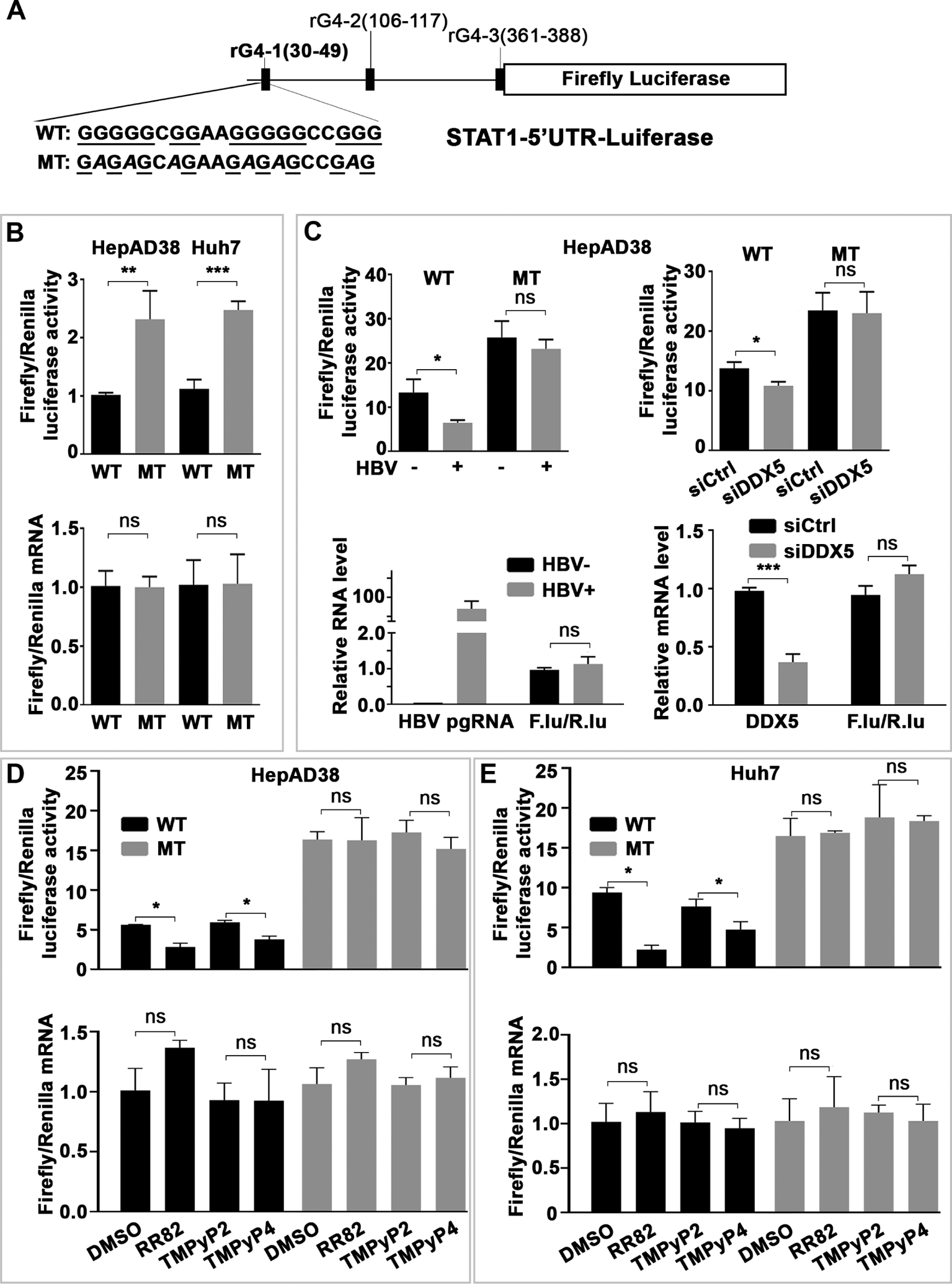

Employing an expression vector driven by the SV40 promoter, we cloned nucleotides (nt)+1 to +400 of the 5′UTR of STAT1 upstream of Firefly (F.) luciferase gene. This 5′UTR region contains three putative rG4s, labelled as rG4-1, rG4-2 and rG4-3 (online supplemental figure S3C). Importantly, rG4-1 is located 30 nt downstream from the start of the 5′UTR. Earlier studies demonstrated rG4s situated proximal or within the first 50 nt to the 5′ end of the 5′UTR are functional and effective in repressing translation.37 Based on this reasoning, we focused our analysis on rG4-1 and constructed a mutant (MT) rG4-1 (figure 3A), with G to A substitutions within the putative rG4-1 sequence. Transfection in HepAD38 cells of expression vectors containing WT and MT rG4-1 demonstrated a statistically significant increased F. luciferase activity from MT rG4-1 in comparison with WT rG4-1 vector, while no changes were observed at the mRNA level, both in HepAD38 and Huh7 cells (figure 3B). Mutational analyses of rG4-2 and rG4-3 sequences excluded a similar role on STAT1 expression (online supplemental figure S4A,B). Next, we examined the effect of HBV replication, using HepAD38 cells, on F. luciferase activity expressed from WT and MT rG4-1 vectors. HBV replication reduced F. luciferase activity only from the WT rG4-1 containing vector, without an effect on F. luciferase mRNA expression (figure 3C). Similar results were observed by siRNA knockdown of DDX5 (siDDX5) (figure 3C). Employing these expression vectors, we also tested the effect of the G4-stabilising compounds RR82 and TMPyP4. Both drugs reduced expression only from the WT rG4-1 vector, without an effect on mRNA levels of F. luciferase, tested in HepAD38 (figure 3D) and Huh7 (figure 3E) cells. Taken together, these results identify the rG4-1 sequence as a functional element in 5′UTR of STAT1 mRNA, regulating its translation.

Figure 3.

G-quadruplex (rG4) regulates STAT1 expression post-transcriptionally. (A) Human STAT1 5’UTR upstream of Firefly (F.) luciferase reporter, driven from SV40 promoter. Putative rG4 sequences in 5’UTR indicated as rG4-1, rG4-2 and rG4-3. WT rG4-1 nucleotide sequence is shown. Italics indicate site-directed changes in mutant MT-rG4-1. (B–E) Ratio of Firefly/Renilla luciferase activity at 24 hours after cotransfection of WT or MT STAT1-5’UTR-F. Luciferase and Renilla-Luciferase expression plasmids. (Lower panels) Ratio of Firefly/Renilla luciferase mRNAs quantified by qRT-PCR. (B) HepAD38 and Huh7 cells. (C) HepAD38 cells with (+) or without (−) HBV replication for 5 days. (D) HepAD38 cells and (E) Huh7 cells treated with indicated G-quadruplex stabilising drugs (5 μM) for 24 hours. Statistical analysis from three independent biological replicates. *P<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. 5′UTR, 5′untranslated region; NS, not significant.

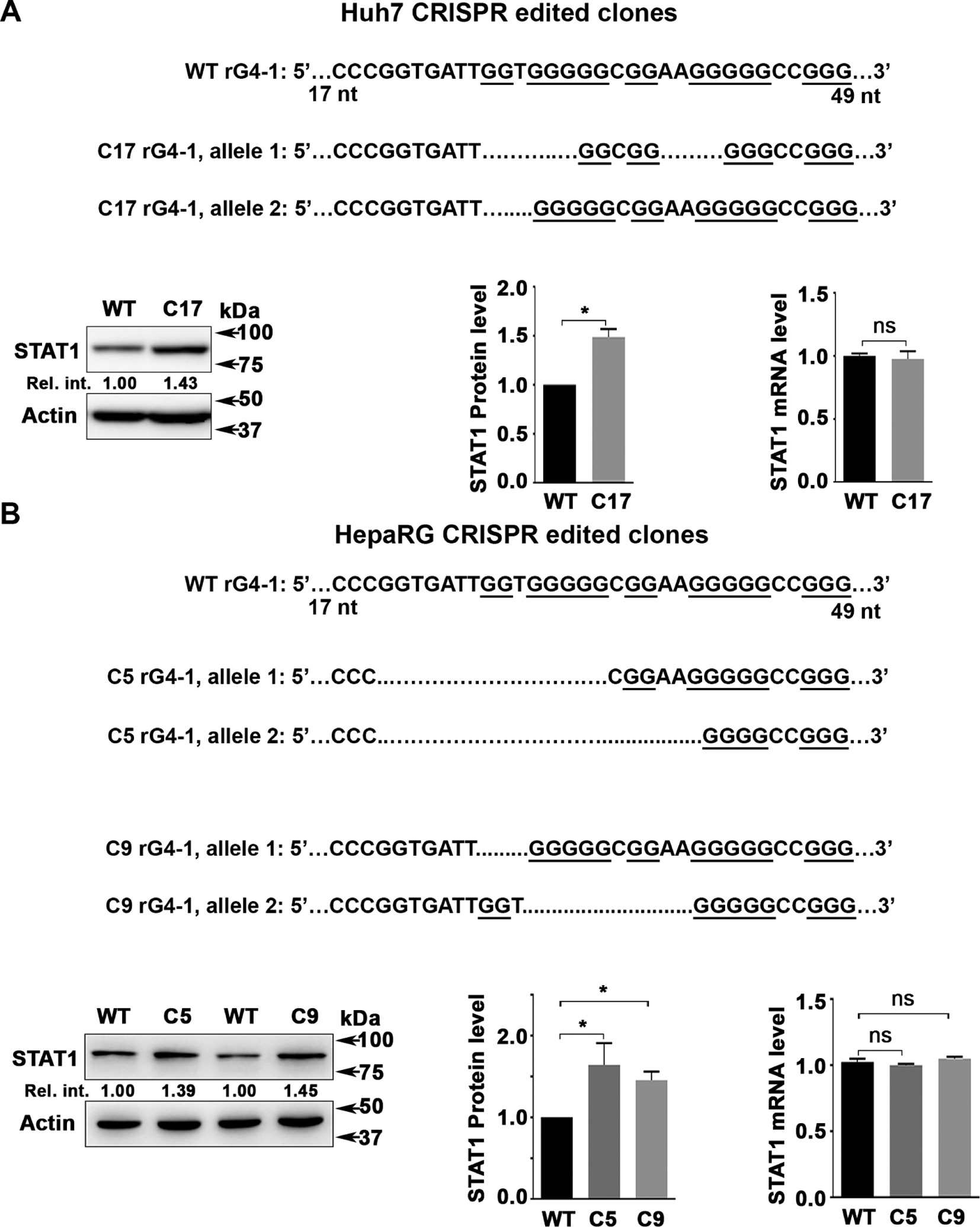

Genomic editing of rG4-1 increases STAT1 protein levels

Using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9 technology,38 we edited the genomic rG4-1 sequence of STAT1 in Huh7 (figure 4A) and HepaRG (figure 4B) cell lines. Several clones were isolated and sequenced, and protein and mRNA levels of STAT1 were determined (figure 4 and online supplemental figure S5). DNA sequencing of HepaRG clones C5 and C9 (online supplemental figure S5) demonstrated C5 cells contain rG4-1 deletions in both alleles, while C9 cells have rG4 changes only in one allele (figure 4B). All clones analysed from Huh7 and HepaRG cells exhibited statistically significant and reproducible increases in protein level of STAT1 in comparison with WT (unedited) cells, while STAT1 mRNA levels remained unchanged (figure 4). These results are also supported by luciferase reporter assays containing the edited rG4-1 sequences (online supplemental figure S6).

Figure 4.

Genomic editing of rG4-1 increases STAT1 protein levels. (A) Sequence of CRIPSR/Cas9 edited rG4-1 sequence in (A) Huh7 and (B) HepaRG cells. Immunoblot of STAT1 in indicated cell lines. Right panels, quantification of STAT1 protein by ImageJ software, and qRT-PCR of STAT1 mRNA, from three independent biological replicates. Error bars indicate mean±SEM. *P<0.05. NS, not significant.

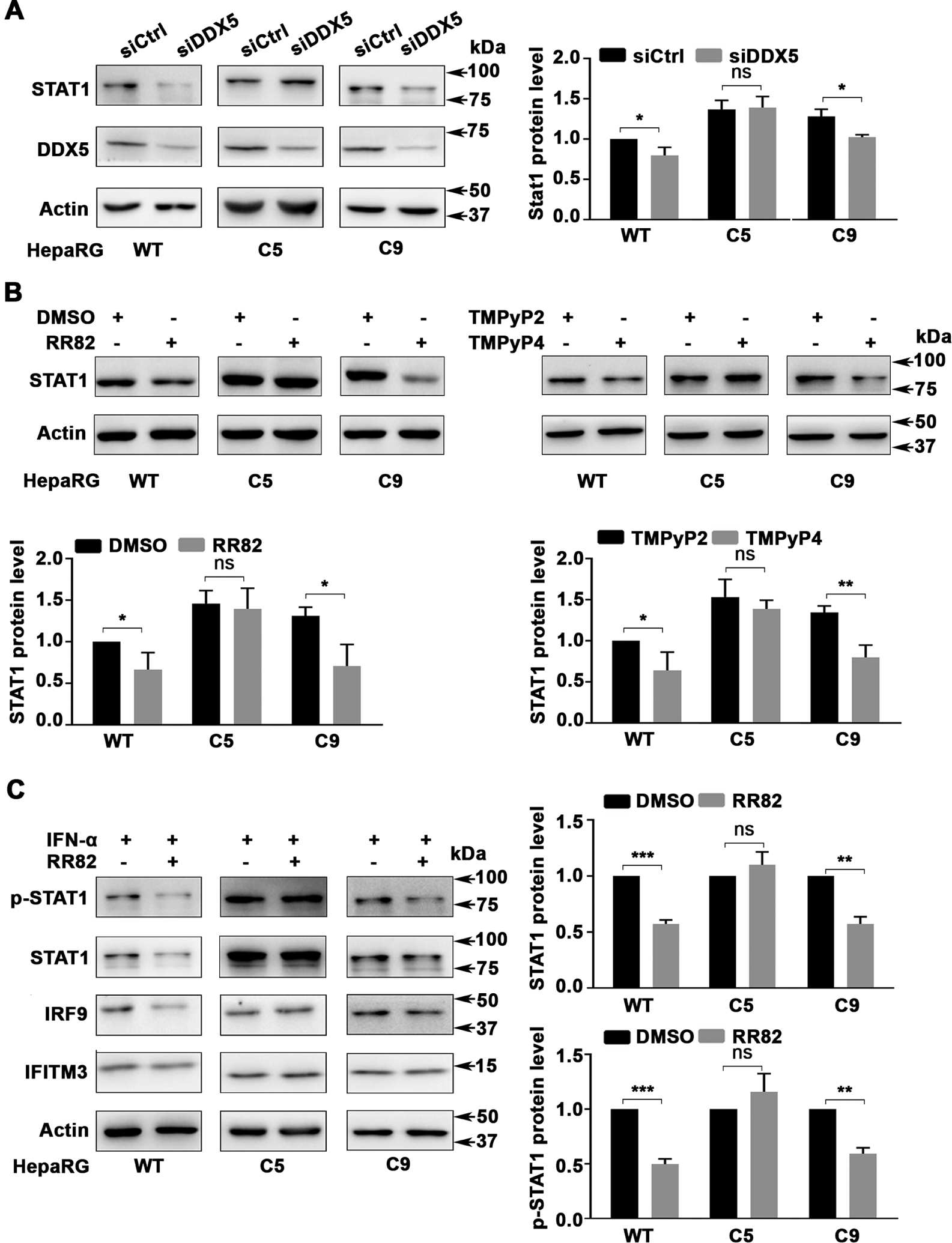

Interestingly, DDX5 knockdown by transfection of DDX5 siRNA had no effect on STAT1 protein levels of clone C5, containing edited rG4 sequence on both STAT1 alleles (figure 5A). By contrast, siDDX5 reduced STAT1 protein levels in WT and C9 cells (figure 5A). Likewise, STAT1 protein levels of clone C5 were resistant to G4-stabilising drugs RR82 and TMPyP4, while these compounds reduced STAT1 levels in both WT and C9 cells (figure 5B). Next, we examined the IFN response of WT, C5 and C9 cells as a function of cotreatment with RR82 (figure 5C). In contrast to WT and C9 cells, the IFN-α response of C5 cells was not inhibited by RR82, in terms of STAT1 protein level and activation, as well as induction of IRF9 and IFITM3 (figure 5C and online supplemental figure S7). These results support that both alleles of clone C5 contain nonfunctional rG4-1 structures in 5′UTR of STAT1 mRNA.

Figure 5.

Effect of G-quadruplex stabilising drugs on rG4-1 edited HepaRG cells. Immunoblots of indicated proteins using lysates from indicated HepaRG cells (WT, C5 and C9). (A) After transfection of siCtrl or siDDX5 RNA for 48 hours, (B) following treatment with RR82 (5 μM), TMPyP4 (5 μM) or TMPyP2 (5 μM) for 48 hours and (C) treatment with RR82 (5 μM) for 48 hours in combination with IFN-α (500 ng/mL) for the last 24 hours. quantification (A–C) from three independent biological replicates. Error bars indicate mean±SEM. *P<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. IFN, interferon; NS, not significant.

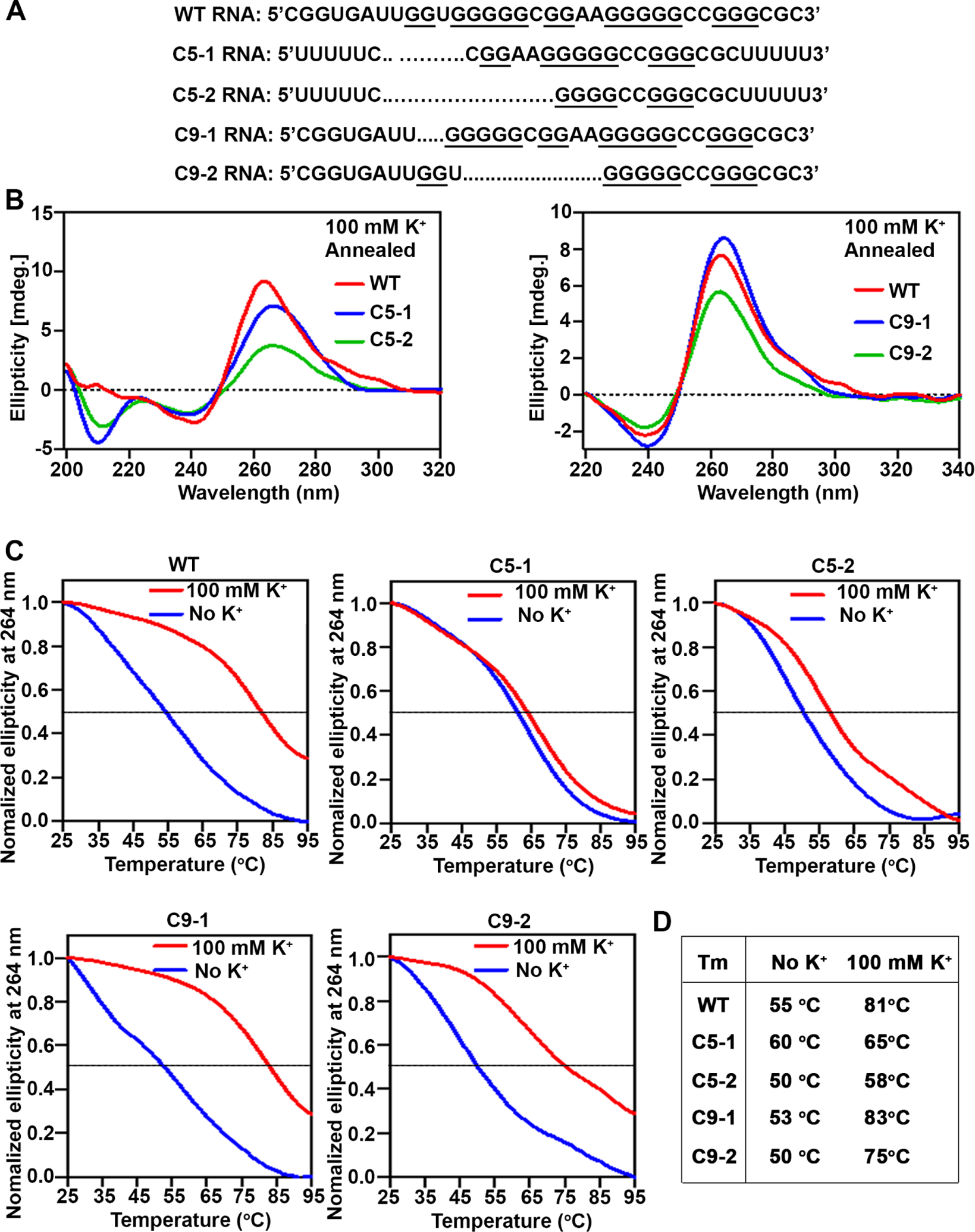

The rG4-1 sequence of STAT1 forms G-quadruplex in vitro

To directly determine whether the rG4-1 sequence in 5′UTR of STAT1 indeed forms a G-quadruplex structure, we employed CD spectroscopy, a method that enables study of nucleic acid secondary structure32 39. RNA oligonucleotides were synthesised (figure 6A) that corresponded to the indicated sequences of rG4-1 found in WT STAT1 mRNA, and in each allele of clones C5 and C9. Since G4 oligonucleotides can form higher order structures, we included U-streches at the 5′ and 3′ of the indicated RNA oligonucleotides and confirmed these RNA molecules were in monomeric form, employing native PAGE (online supplemental figure S8). The CD spectrum and thermal stability of these RNA oligonucleotides were studied as a function of K+ addition (100 mM), a cation that stabilises G4 structures.40 The melting temperature (Tm) of each RNA oligonucleotide is shown (figure 6D). Addition of 100 mM KCl increased the Tm of the WT, C9-1 and C9-2 RNA oligonucleotides, supporting formation of stable rG4 structures. By contrast, oligonucleotide C5-1 and C5-2 exhibited no or very small Tm increase in comparison with WT. These results indicate the WT, C9-1 and C9-2 sequences form stable rG4 structures, whereas C5-1 and C5-2 lack formation of this structure. These biophysical results are congruent with our biological data and demonstrate the role of rG4-1 structure in STAT1 translational control.

Figure 6.

The rG4-1 sequence in 5’UTR of STAT1 mRNA forms G-quadruplex. (A) Synthetic RNA oligonucleotides of WT STAT1 rG4-1 and corresponding mutants in HepaRG clones C5 and C9. (B) CD spectroscopy measurement and (C) melting curves of RNA oligonucleotides annealed by heating to 95°C and slowly cooled down to room temperature. (D) Melting temperature (TM), without and with (100 mM) KCl, calculated from A to C.

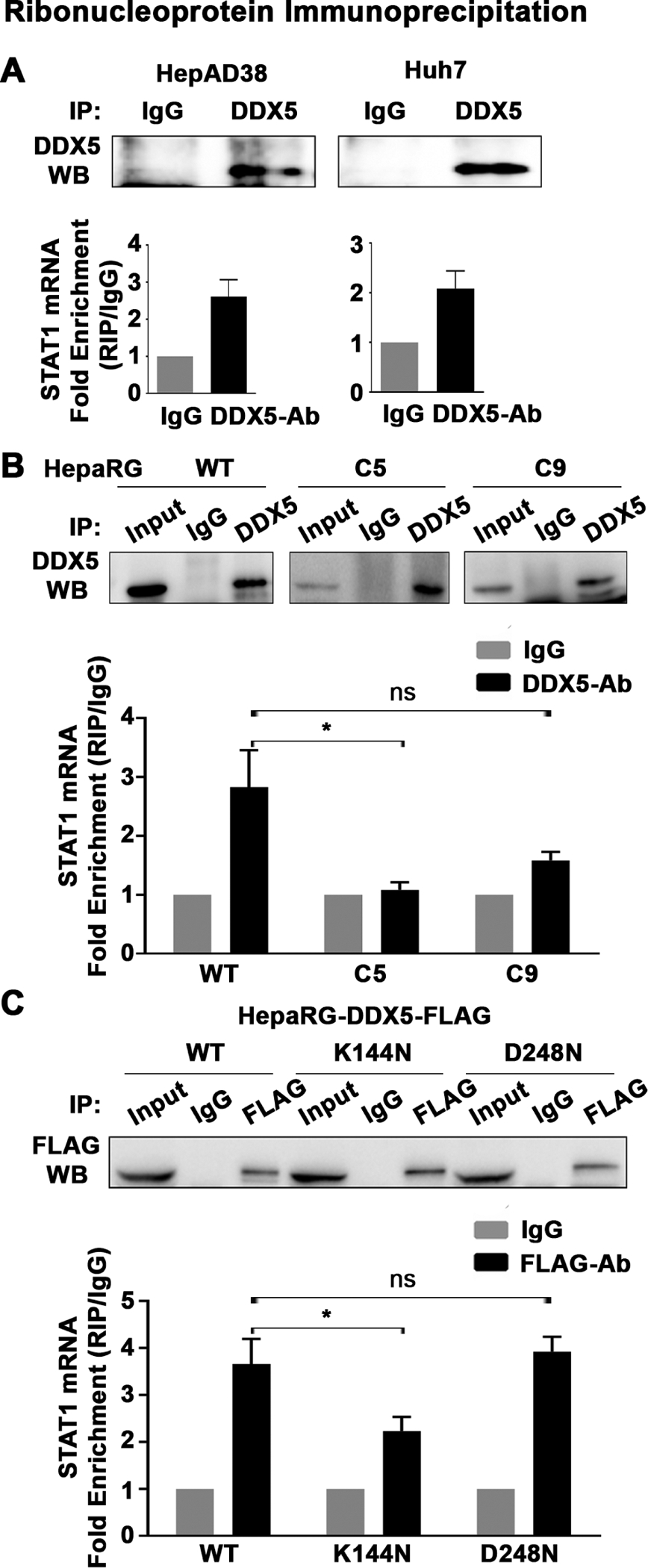

DDX5 selectively binds STAT1 mRNA with WT rG4-1

To determine whether DDX5 interacts directly with STAT1 mRNA, we performed ribonucleoprotein immunoprecipitation (RIP) assays employing DDX5 antibody and IgG as negative control. In HepAD38 and Huh7 cells endogenous, immunoprecipitated DDX5 was found in association with STAT1 mRNA, while IgG did not exhibit such association (figure 7A). Next, we performed RIP assays in HepaRG cells, WT and clones C5 and C9. Interestingly, endogenous DDX5 associated with STAT1 mRNA in WT and clone C9 cells, while STAT1 mRNA expressed in clone C5, containing mutated rG4-1 sequence on both alleles, lacked binding to DDX5 (figure 7B).

Figure 7.

DDX5 binds STAT1 mRNA. Ribonucleoprotein immunoprecipitation (RIP) assays with DDX5 antibody performed in (A) HepAD38, Huh7, and (B) HepaRG WT, C5 and C9 cells. DDX5 enriched RNAs quantified by qRT-PCR using STAT1 primers. Results are from three biological replicates. *P<0.05. (C) RIP assays with FLAG antibody performed using HepaRG-DDX5-WT-FLAG, HepaRG-DDX5-K144N-FLAG and HepaRG-DDX5-D248N-FLAG expressing cell lines. FLAG antibody immunoprecipitated RNAs quantified by qRT-PCR using STAT1 primers. Results are from three biological replicates. *P<0.05. NS, not significant.

To determine whether the enzymatic RNA helicase activity of DDX5 is required for resolving the rG4 STAT1 mRNA structure, we compared the STAT1 mRNA binding potential of WT DDX5 and two mutant forms of DDX5. Mutant DDX5-K144N lacks ATPase activity41 and DDX5-D248N binds RNA but does not remodel it.18 Employing HepaRG cell lines expressing the WT and indicated DDX5 mutants, we performed RIP assays (figure 7C). DDX5-K144N exhibited significantly reduced binding to endogenous STAT1 mRNA, in comparison with WT and DDX5- D248N (figure 7C), supporting the requirement of ATP hydrolysis for STAT1 mRNA binding.

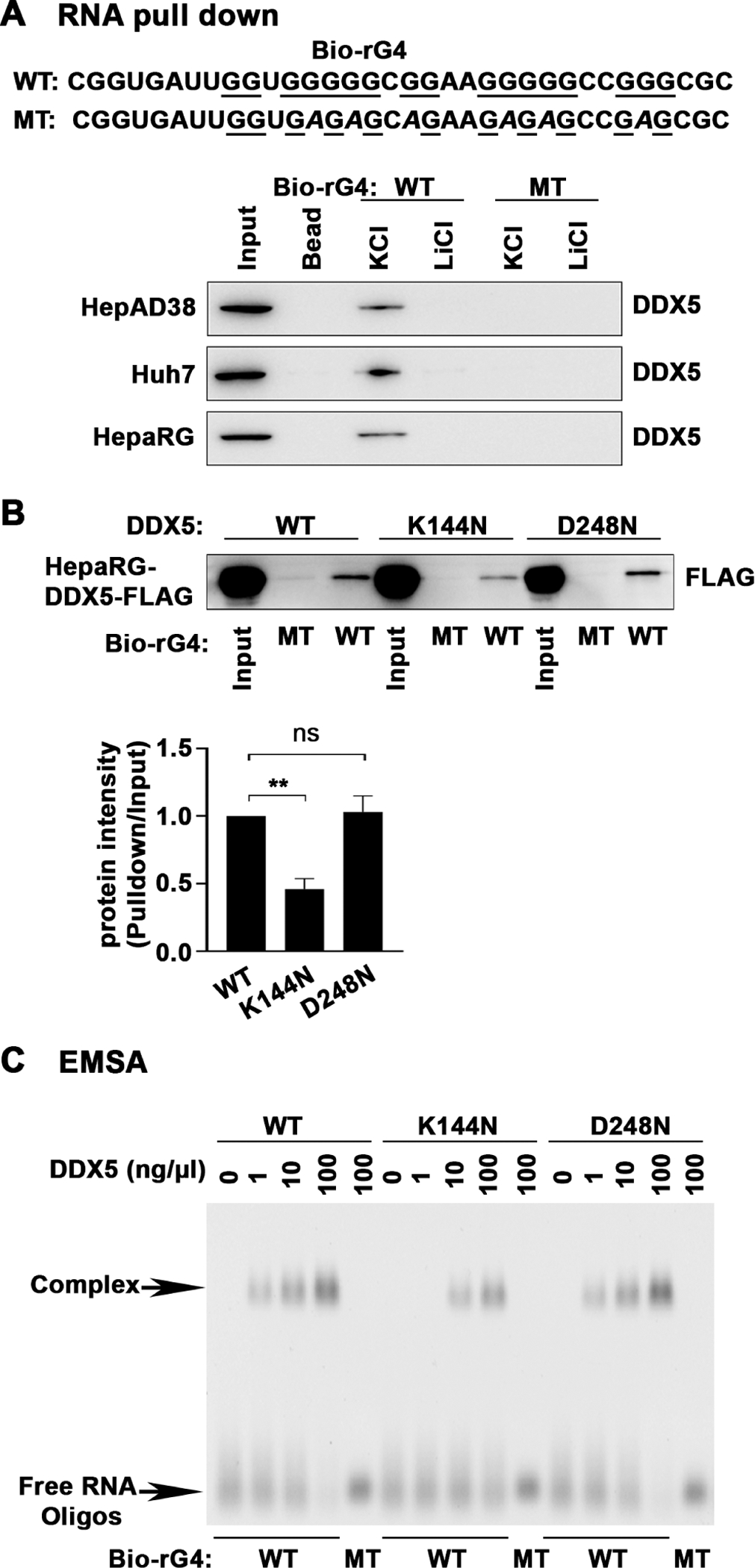

To further confirm that DDX5 binds the rG4-1 sequence, biotinylated oligonucleotides containing WT or mutant rG4-1 (figure 8A) were incubated in 100 mM K+ that stabilises the G4 structure or 100 mM Li+ that does not.40 Mutant rG4-1 does not form stable G4 structure even in the presence of 100 mM K+, determined by CD spectroscopy (online supplemental figure S9A). Next, prefolded RNA oligonucleotides incubated with lysates from HepAD38, Huh7 and HepaRG cells were bound to streptavidin beads, and the retained proteins analysed by DDX5 immunoblots. Indeed, these pull-down assays show DDX5 selectively binds the WT rG4-1, whose structure is stabilised by 100 mM K+ (figure 8A). We also employed the pull-down using the biotinylated WT and MT rG4-1 RNA oligonucleotides to confirm the requirement of the RNA helicase activity in this process. Indeed, both the WT and DDX5-D248N proteins, expressed in HepaRG cells, exhibited enhanced and selective binding to the WT rG4-1 RNA oligo in comparison with the inactive DDX5-K144N (figure 8B).

Figure 8.

DDX5 binds rG4-1 structure of 5’UTR of STAT1 mRNA. (A) (Upper panel) Sequence of synthetic biotinylated RNA oligonucleotides, Bio-rG4 WT and MT. (Lower panel) RNA pull-down assays using Bio-rG4 WT and MT in 100 mM KCl or 100 mM LiCl, bound to lysates from indicated cell lines, followed by immunoblots with DDX5 antibody. (B) RNA pull-down assays using Bio-rG4 WT and MT in 100 mM KCl, bound to lysates from HepaRG-DDX5-WT-FLAG, HepaRG-DDX5-K144N-FLAG and HepaRG-DDX5-D248N-FLAG expressing cell lines, followed by immunoblots with FLAG antibody. A representative assay is shown from three independent experiments. Band intensities quantified by ImageJ. Results are from three biological replicates. **P<0.01. (C) EMSA using Bio-rG4 WT and MT RNA oligonucleotides, in binding reactions containing indicated amount of immunoaffinity purified DDX5-WT, DDX5-K144N and DDX5-D248N, analysed by native gel electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose gels and visualised by staining with SYBR-Gold dye (ThermoFisher) and ChemiDoc touch imaging system. 5’UTR, 5′untranslated region; EMSA, electrophoretic mobility shift assay; ns, not significant.

Lastly, to directly demonstrate that DDX5 forms an RNA–protein complex with the WT rG4-1 RNA oligonucleotide, we performed EMSAs using increasing amounts of affinity purified WT and DDX5 mutant proteins (figure 8C, online supplemental figure S9B). The WT and DDX5-D248N proteins exhibited selective and enhanced complex formation with WT but not MT rG4-1 RNA oligonucleotides. By contrast, DDX5-K144N exhibited approximately 10-fold reduced binding to the WT rG4-1 RNA (figure 8C), further supporting the requirement of the enzymatic activity of DDX5 in resolving the rG4 structure in the 5′UTR of STAT1 mRNA.

STAT1 expression in liver cancer cell lines and HBV-related liver tumours

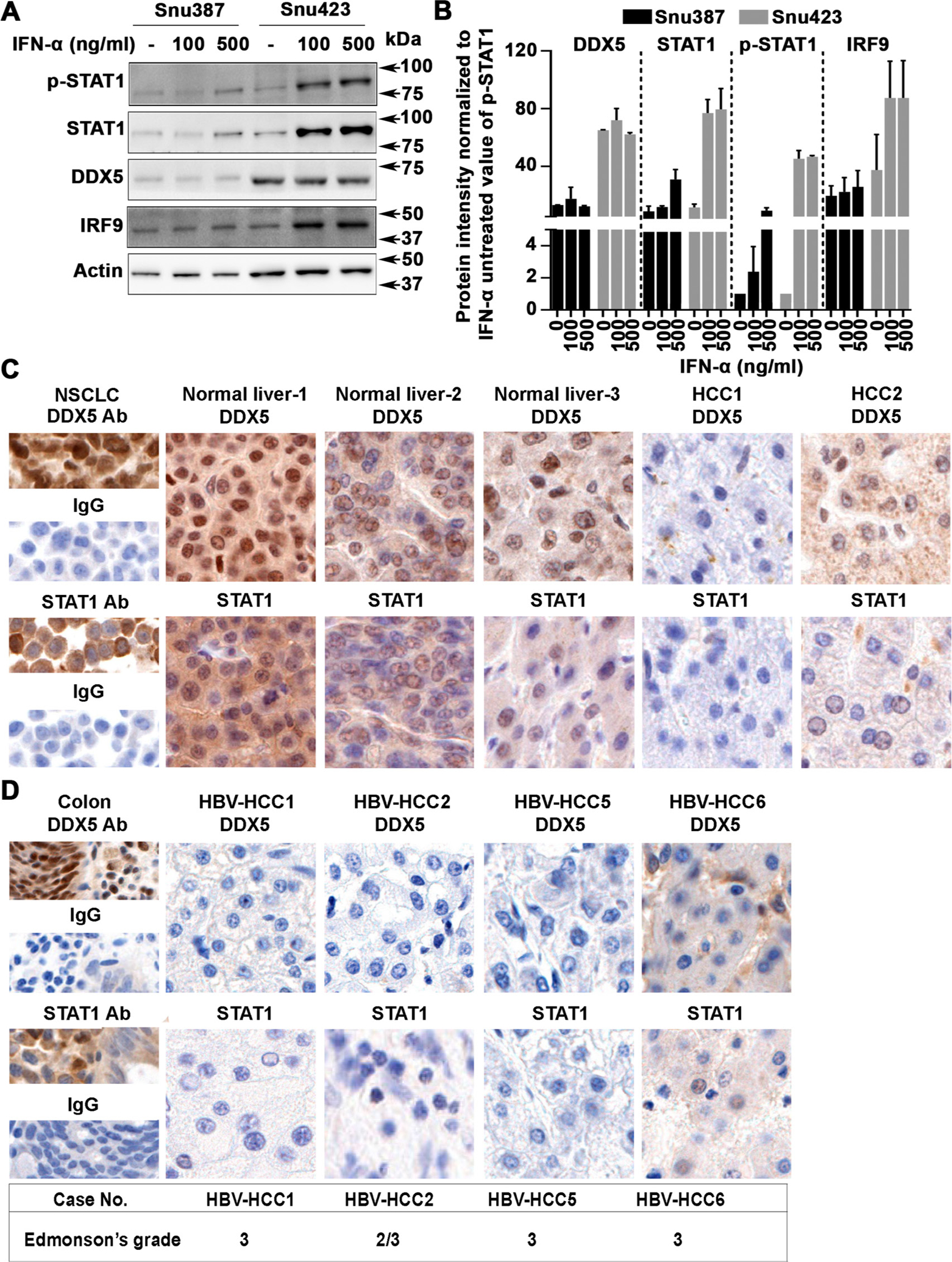

To further establish the biological connection between DDX5 and STAT1 protein levels relative to IFN response, we quantified IFN-α response in liver cancer cell lines expressing different levels of DDX5 protein. We compared cell lines Snu387 versus Snu423, and CLC15 versus CLC46,30 by performing immunoblots of lysates treated with increasing amount of IFN-α for 12 hours (figure 9A and online supplemental figure S10A). Following quantification of the immunoblots, the signal of DDX5, STAT1, p-STAT1 and IRF9 was normalised to the baseline p-STAT1 signal, obtained without IFN-α treatment (figure 9B). The results show the level of STAT1 protein, STAT1 activation and IFN-α response (IRF9) is proportional to the level of DDX5 (figure 9B). Importantly, the basal expression level of STAT1 mRNA is significantly lower in Snu423 cells in comparison with Snu387 cells (online supplemental figure S10B).

Figure 9.

DDX5 expression level in liver cancer cell lines and liver tumours. (A) Immunoblots using lysates from indicated cell lines treated with IFN-α (100 and 500 ng/mL) for 12 hours. (B) Quantification shows ratio of DDX5, STAT1, p-STAT1 and IRF9 relative to level of p-STAT1 in IFN-α untreated cells. Results are average from three independent experiments. (C) Immunohistochemistry of normal liver, HCCs, and (D) HBV-related HCCs, was performed as described.18 Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) tissue and normal human colon tissue were used as positive controls, as indicated, with DDX5 and STAT1 antibodies versus IgG. IFN, interferon.

Next, we analysed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) the expression of DDX5 and STAT1 proteins in human normal liver tissue and a small set of HCCs (figure 9C) including HBV-related HCCs (figure 9D). Normal liver tissue exhibited positive immunostaining for both DDX5 and STAT1, in comparison with other controls. By contrast, HCC1 lacked positive immunostaining for both proteins, whereas HCC2 displayed a weak signal (HCC1 and HCC2 are of unknown aetiology). Figure 9D shows IHC of HBV-related HCCs; we observed absence of immunostaining for both DDX5 and STAT1 in Edmonson’s grade 3 HBV-related HCCs, supporting our mechanistic in vitro observations.

DDX5 knockdown reduces the antiviral effect of IFN-α on HBV replication

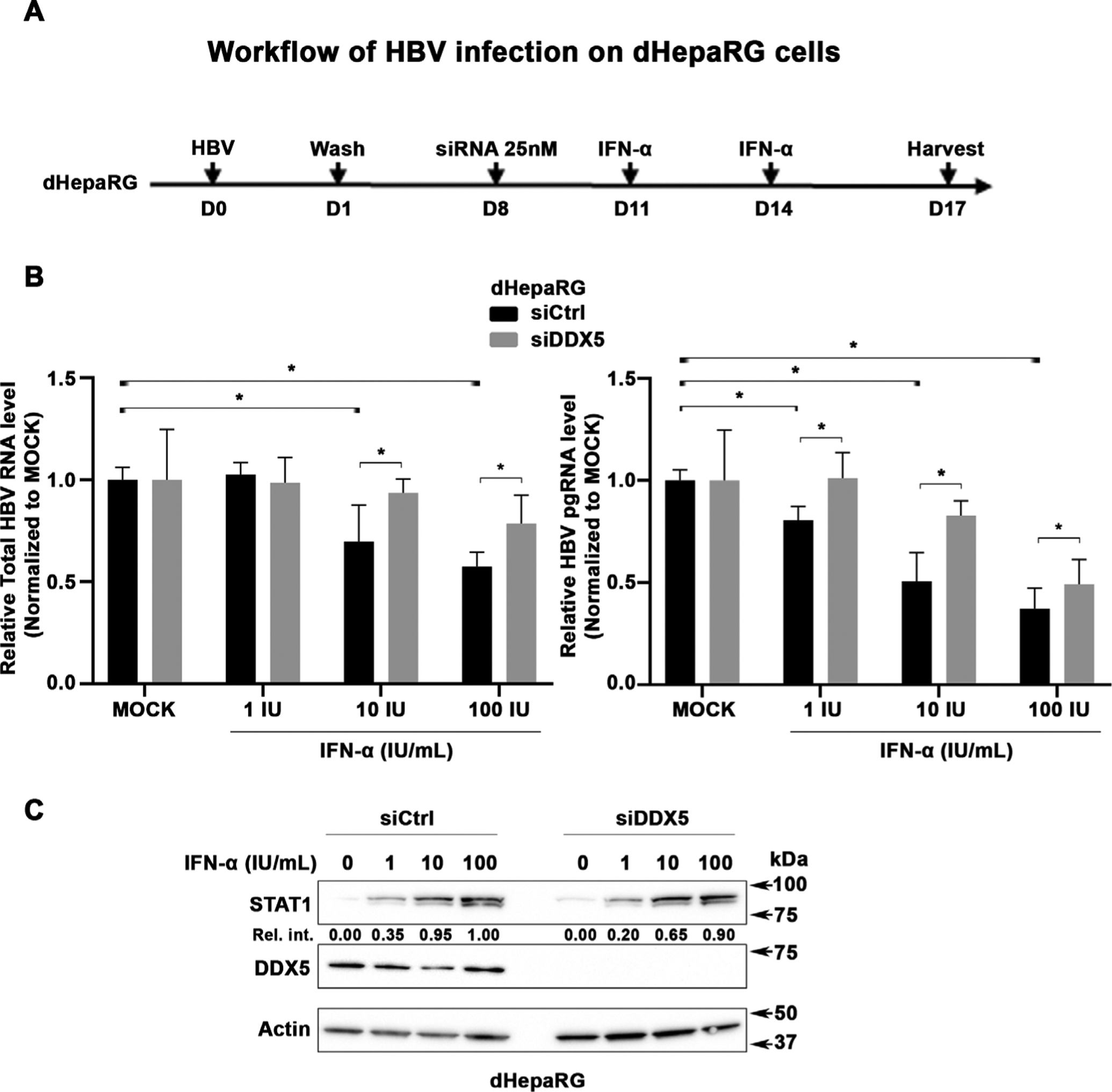

We employed the HBV infection model of differentiated dHepaRG cells to examine effect of DDX5 knockdown on HBV replication as a function of IFN-α treatment. dHepaRG cells following establishment of HBV infection, at day 8 p.i., were transfected with siCtrl or siDDX5, followed by IFN-α addition, starting on day 11–17 p.i., as indicated (figure 10A). IFN-α treatment significantly repressed transcription of viral RNAs (figure 10B, online supplemental figure S11). By contrast, the level of expression of viral RNAs did not become significantly reduced by IFN-α in DDX5 knockdown cells (figure 10, online supplemental figure S11). Furthermore, the protein level of STAT1 in response to IFN-α treatment is reduced in DDX5 knockdown cells in comparison to siCtrl (figure 10C). These results support that the protein level or state of activation of DDX5 is a parameter modulating the IFN-α response in the context of HBV infection.

Figure 10.

DDX5 knockdown reduces antiviral IFN-α effect on HBV replication. (A) Diagram illustrates the workflow of HBV infection using dHepaRG cells; infection with HBV was carried out at moi=500 in the presence of 4% Peg8000, in triplicates. siRNAs (25 nM final concentration) control (siCtrl) or DDX5 (Dharmacon) were transfected on day 8 p.i.; IFN-α added on days 11 and 14 p.i. (B) Quantification of total HBV RNA and pgRNA by qRT-PCR as previously described.53 Results are from two independent experiments performed in triplicates. *P<0.05. (C) Immunoblots of whole cell extracts (WCE) from HBV-infected cells, with indicated antibodies. Relative intensity (Rel. Int.) is the ratio of STAT1/actin, quantified by ImageJ software. A representative assay is shown from two independent experiments. IFN, interferon; moi, multiplicity of infection; p.i., postinfection.

DISCUSSION

Herein, we report the translational control of STAT1, a transcription factor essential for all types (I/III) of IFN signalling, via a G-quadruplex (rG4) structure located at the 5′UTR of STAT1 mRNA. RNA helicase DDX5 resolves this rG4 structure, thereby enabling STAT1 translation. Significantly, this post-transcriptional regulation of STAT1 expression is a cell intrinsic mechanism that influences the dynamic range of IFN response, dependent on protein level and activity of DDX5. The RNA helicase DDX5 regulates every aspect of RNA metabolism42 and also serves as a barrier to pluripotency.43 Interestingly, it has been noted that pluripotent stem cells are refractory to IFN signalling,44 45 although the mechanism is not yet understood. It is currently unknown whether absence of DDX5 expression or activity contributes to lack of innate immune response in pluripotent stem cells.44 45

G-quadruplexes (G4) are non-canonical, secondary DNA or RNA structures formed by guanine rich sequences.24 25 46 DNA G4 structures are found in gene promoters, particularly of oncogenes, regulating their transcription.47 Interestingly, recent studies demonstrated that DDX5 resolves both RNA and DNA G4 structures, including a G4 structure found in the MYC promoter, enhancing its transcriptional activity.28 rG4s are primarily located in 5′UTR or 3′UTR of mRNAs, playing important roles in RNA biology, from splicing, stability, mRNA targeting and translation.24 46 rG4 structures have been identified by various methods in the 5′UTR of NRAS,26 Zic-1,48 Nkx2–549 mRNAs, among other genes,24 46 regulating their translation. Herein, we demonstrate by pharmacologic, molecular and biophysical approaches the functional significance of the rG4 structure in the 5′UTR of STAT1 mRNA. Interestingly, this rG4 sequence in the 5′UTR of STAT1 is conserved in primates (online supplemental figure S12A), and several polymorphisms are found in the human genome at the 5′UTR of STAT1 (online supplemental figure S12B).

We demonstrate that G4 structure-stabilising compounds RR82, PhenDC3 and TMPyP4 reduced the protein level of both STAT1 and NRAS, used as positive control, without affecting STAT1 mRNA level (figure 2). After excluding other post-transcriptional modes of STAT1 regulation, we focused on the rG4-1 sequence located in proximity to the 5′ end of the STAT1 5′UTR, since it had been identified as a high probability rG4 sequence by the transcriptomic study of Kwok et al.27 Indeed, using an SV40-driven Luciferase reporter, containing the STAT1 5′UTR (nt+1 to +400) upstream from F. luciferase, we demonstrate that G4 structure-stabilising compounds suppressed the protein synthesis but not mRNA level of the WT rG4-1 containing luciferase vector (figure 3). We also edited the genome of Huh7 and HepaRG cells by the CRISPR/Cas9 approach and generated alterations (deletions) of the rG4-1 sequence of STAT1 gene (figure 4). When both alleles harboured the edited rG4-1 sequence, as in HepaRG clone C5, STAT1 protein levels were increased. Significantly, expression of STAT1 in clone C5 was resistant both to DDX5 knockdown (figure 5A), and the inhibitory effect of G4-stabilising compounds (figure 5B). Circular dichroism and thermal stability measurements directly demonstrated formation of G-quadruplex only by WT and C9 rG4-1 sequences (figure 6), supporting the biological data. RIP assays using antibody to endogenous DDX5 protein showed lack of DDX5 binding to STAT1 mRNA from clone C5, containing edited rG4-1 sequence in both alleles. By contrast, DDX5 bound to STAT1 mRNA encoding the WT and C9 rG4-1 sequence (figure 7). Importantly, the RNA helicase activity of DDX5 is required for binding STAT1 mRNA, shown by the reduced STAT1 mRNA binding of the DDX5-K144N mutant that lacks ATPase activity (figure 7). These results were further verified by RNA pull-down assays using synthetic RNA oligonucleotides under K+ conditions enabling formation of the G-quadruplex structure, thereby confirming endogenous DDX5 recognises the G-quadruplex found at the 5′UTR of STAT1 mRNA (figure 8). Moreover, employing pull-down assays, we further confirmed the enzymatic activity of DDX5, modelled by DDX5-K144N mutant, is required for WT rG4-1 binding (figure 8). In addition, EMSAs directly demonstrated complex formation between the WT rG4-1 RNA and DDX5, while DDX5-K144N exhibited significantly reduced complex formation (figure 8).Taken these results together, we conclude, the rG4-1 sequence in 5′UTR of human STAT1 mRNA assumes a G-quadruplex secondary structure. This rG4 structure, stabilised by G4-stabilising compounds RR82, PhenDC3 and TMPyP4, suppresses STAT1 mRNA translation. RNA helicase DDX5 resolves the rG4 structure, enabling STAT1 mRNA translation.

Regarding the biological significance of this mechanism, first, we compared STAT1 levels and the IFN response using two sets of liver cancer cell lines expressing low versus high DDX5, namely, Snu387 vs Snu423, and CCL15 and CCL46 derived from HBV-related HCCs.30 We observed the magnitude of the IFN-α response is a cell intrinsic property, dependent on DDX5 (figure 9A–B and online supplemental figure S10). Although the ATPase activity of DDX5 (42) is required for binding to STAT1 mRNA (figure 8), recent studies have shown that PRMT5-mediated arginine methylation of DDX5 modulates its function in resolving DNA:RNA hybrids.50 However, how the activity of DDX5 is regulated in different cellular contexts or in response to IFN is presently not understood (online supplemental figure S13). Certainly, the regulation of DDX5 will add another level of complexity to this novel mechanism of IFN response. In the context of HBV infection and IFN treatment, knockdown of DDX5 reduced the antiviral effect of IFN-α, via STAT1 protein reduction (figure 10). However, a lot remains to be understood of STAT1 regulation. Specifically, recent studies have identified additional mechanisms that regulate STAT1 mRNA stability and translation, involving lncRNA Sros1 and RNA binding protein CAPRIN1, in response to IFN-γ.51 Thus, STAT1 expression involves multipronged regulation, the integration of which remains to be understood.

We also show that in comparison with normal liver, in HCCs and HBV-related HCCs analysed herein, the absence of DDX5 also corresponds to absence of STAT1 immunostaining (figure 9). Absence of STAT1 expression could provide an explanation for the lack of IFN-α response observed in many chronically HBV infected patients with HCC.16 Interestingly, a positive indicator for IFN-α responsiveness in HBV-infected patients with HCC16 is expression of IFIT3, a STAT1-regulated gene.15 In addition, it is presently unknown whether this mechanism of DDX5-dependent STAT1 translational regulation is also linked to the immunotherapy response of patients with HCCs. Our earlier studies identified downregulation of DDX5 to be associated with poor prognosis HBV-related HCC18 and hepatocyte reprogramming to a less-differentiated state exhibiting features of hCSCs,23 in agreement with the role of DDX5 as a barrier to pluripotency.43 Regarding immunotherapy, which is based on PD-1 blockade, the PD-L1,2 ligands are induced in tumours by IFN gamma, leading to immune evasion.52 According to the mechanism described herein, absence or downregulation of DDX5 in HCCs will result in absence or reduced protein of STAT1 and in turn reduced PD-L1 expression.52

Supplementary Material

Significance of this study.

What is already known on this subject?

Transcription factor STAT1 is involved in all types (I/III) of interferon signalling.

What are the new findings?

RNA helicase DDX5 regulates STAT1 translation.

DDX5 resolves a secondary structure called G-quadruplex located at 5′UTR of STAT1 mRNA.

Downregulation of DDX5 reduces antiviral effect of interferon alpha on hepatitis B virus replication.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

DDX5 could serve as indicator of interferon response.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH grants DK044533 to OA and CA177585 to DY. Shared Resources (Genomics and Bioinformatics Facilities) supported by NIH grant P30CA023168 to Purdue Center for Cancer Research, and NIH/NCRR RR025761.

Footnotes

Additional supplemental material is published online only. To view, please visit the journal online (http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323126).

Competing interests None declared.

Ethics approval Ethics approval obtained by Purdue University (Ref. ID #97-010-21).

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. All data are available for review.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stark GR, Darnell JE. The JAK-STAT pathway at twenty. Immunity 2012;36:503–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stanifer ML, Pervolaraki K, Boulant S. Differential regulation of type I and type III interferon signaling. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen K, Liu J, Liu S, et al. Methyltransferase SETD2-Mediated methylation of STAT1 is critical for interferon antiviral activity. Cell 2017;170:492–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krämer OH, Knauer SK, Greiner G, et al. A phosphorylation-acetylation switch regulates STAT1 signaling. Genes Dev 2009;23:223–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu S, Jiang M, Wang W, et al. Nuclear RNF2 inhibits interferon function by promoting K33-linked STAT1 disassociation from DNA. Nat Immunol 2018;19:41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider WM, Chevillotte MD, Rice CM. Interferon-Stimulated genes: a complex web of host defenses. Annu Rev Immunol 2014;32:513–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ladner SK, Otto MJ, Barker CS, et al. Inducible expression of human hepatitis B virus (HBV) in stably transfected hepatoblastoma cells: a novel system for screening potential inhibitors of HBV replication. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1997;41:1715–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lucifora J, Durantel D, Testoni B, et al. Control of hepatitis B virus replication by innate response of HepaRG cells. Hepatology 2010;51:63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017;389:56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abou-Alfa GK, Meyer T, Cheng A-L, et al. Cabozantinib in patients with advanced and progressing hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2018;379:54–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Llovet JM, Bruix J. Molecular targeted therapies in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2008;48:1312–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taniguchi T, Takaoka A. A weak signal for strong responses: interferon-alpha/beta revisited. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2001;2:378–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Platanias LC. Mechanisms of type-I-and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nat Rev Immunol 2005;5:375–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lebossé F, Testoni B, Fresquet J, et al. Intrahepatic innate immune response pathways are downregulated in untreated chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol 2017;66:897–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao S, Li D, Zhu H-Q, et al. RIG-G as a key mediator of the antiproliferative activity of interferon-related pathways through enhancing p21 and p27 proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:16448–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Y, Zhou Y, Hou J, et al. Hepatic IFIT3 predicts interferon-α therapeutic response in patients of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2017;66:152–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang H, Diab A, Fan H, et al. Plk1 and HOTAIR accelerate proteasomal degradation of SUZ12 and ZNF198 during hepatitis B virus-induced liver carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 2015;75:2363–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang H, Xing Z, Mani SKK, et al. Rna helicase DEAD box protein 5 regulates polycomb repressive complex 2/Hox transcript antisense intergenic RNA function in hepatitis B virus infection and hepatocarcinogenesis. Hepatology 2016;64:1033–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mani SKK, Andrisani O. Hepatitis B virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatic cancer stem cells. Genes 2018;9:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Margueron R, Reinberg D. The polycomb complex PRC2 and its mark in life. Nature 2011;469:343–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarmoskaite I, Russell R. Rna helicase proteins as chaperones and remodelers. Annu Rev Biochem 2014;83:697–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jankowsky E, Fairman ME. RNA helicases--one fold for many functions. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2007;17:316–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mani SKK, Yan B, Cui Z, et al. Restoration of RNA helicase DDX5 suppresses hepatitis B virus (HBV) biosynthesis and Wnt signaling in HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Theranostics 2020;10:10957–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bugaut A, Balasubramanian S. 5’-Utr RNA G-quadruplexes: translation regulation and targeting. Nucleic Acids Res 2012;40:4727–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DNA YDG-Q. And RNA. Methods Mol Biol 2035;2019:1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumari S, Bugaut A, Huppert JL, et al. An RNA G-quadruplex in the 5’ UTR of the NRAS proto-oncogene modulates translation. Nat Chem Biol 2007;3:218–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwok CK, Marsico G, Sahakyan AB, et al. rG4-seq reveals widespread formation of G-quadruplex structures in the human transcriptome. Nat Methods 2016;13:841–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu G, Xing Z, Tran EJ, et al. DDX5 helicase resolves G-quadruplex and is involved in MYC gene transcriptional activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:20453–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lucifora J, Durantel D, Belloni L, et al. Initiation of hepatitis B virus genome replication and production of infectious virus following delivery in HepG2 cells by novel recombinant baculovirus vector. J Gen Virol 2008;89:1819–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qiu Z, Li H, Zhang Z, et al. A pharmacogenomic landscape in human liver cancers. Cancer Cell 2019;36:179–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gripon P, Rumin S, Urban S, et al. Infection of a human hepatoma cell line by hepatitis B virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002;99:15655–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hatzakis E, Okamoto K, Yang D. Thermodynamic stability and folding kinetics of the major G-quadruplex and its loop isomers formed in the nuclease hypersensitive element in the human c-myc promoter: effect of loops and flanking segments on the stability of parallel-stranded intramolecular G-quadruplexes. Biochemistry 2010;49:9152–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang L, Yang JL, Byrne S, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-Directed genome editing of cultured cells. Curr Protoc Mol Biol 2014;107:31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu X, Xu Y, Yu S, et al. An efficient genotyping method for genome-modified animals and human cells generated with CRISPR/Cas9 system. Sci Rep 2014;4:6420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ribeiro de Almeida C, Dhir S, Dhir A, et al. Rna helicase DDX1 converts RNA G-quadruplex structures into R-loops to promote IgH class switch recombination. Mol Cell 2018;70:650–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han FX, Wheelhouse RT, Hurley LH. Interactions of TMPyP4 and TMPyP2 with quadruplex DNA. Structural basis for the differential effects on telomerase inhibition. J Am Chem Soc 1999;121:3561–70. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumari S, Bugaut A, Balasubramanian S. Position and stability are determining factors for translation repression by an RNA G-quadruplex-forming sequence within the 5’ UTR of the NRAS proto-oncogene. Biochemistry 2008;47:12664–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lander ES. The heroes of CRISPR. Cell 2016;164:18–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Del Villar-Guerra R, Gray RD, Chaires JB. Characterization of quadruplex DNA structure by circular dichroism. Curr Protoc Nucleic Acid Chem 2017;68:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang J, Lau MW, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Ribozymes and riboswitches: modulation of RNA function by small molecules. Biochemistry 2010;49:9123–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jalal C, Uhlmann-Schiffler H, Stahl H. Redundant role of DEAD box proteins p68 (DDX5) and p72/p82 (Ddx17) in ribosome biogenesis and cell proliferation. Nucleic Acids Res 2007;35:3590–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Linder P, Jankowsky E. From unwinding to clamping - the DEAD box RNA helicase family. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2011;12:505–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li H, Lai P, Jia J, et al. Rna helicase DDX5 inhibits reprogramming to pluripotency by miRNA-Based repression of RYBP and its PRC1-Dependent and -independent functions. Cell Stem Cell 2017;20:571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guo L, Lin L, Wang X, et al. Resolving cell fate decisions during somatic cell reprogramming by single-cell RNA-seq. Mol Cell 2019;73:815–29. e817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo Y-L, Carmichael GG, Wang R, et al. Attenuated innate immunity in embryonic stem cells and its implications in developmental biology and regenerative medicine. Stem Cells 2015;33:3165–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Millevoi S, Moine H, Vagner S. G-Quadruplexes in RNA biology. WIREs RNA 2012;3:495–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qin Y, Hurley LH. Structures, folding patterns, and functions of intramolecular DNA G-quadruplexes found in eukaryotic promoter regions. Biochimie 2008;90:1149–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arora A, Dutkiewicz M, Scaria V, et al. Inhibition of translation in living eukaryotic cells by an RNA G-quadruplex motif. RNA 2008;14:1290–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nie J, Jiang M, Zhang X, et al. Post-Transcriptional regulation of Nkx2–5 by RHAU in heart development. Cell Rep 2015;13:723–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mersaoui SY, Yu Z, Coulombe Y, et al. Arginine methylation of the DDX5 helicase RGG/RG motif by PRMT5 regulates resolution of RNA:DNA hybrids. Embo J 2019;38:e100986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu H, Jiang Y, Xu X, et al. Inducible degradation of lncRNA Sros1 promotes IFN-γ-mediated activation of innate immune responses by stabilizing STAT1 mRNA. Nat Immunol 2019;20:1621–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Garcia-Diaz A, Shin DS, Moreno BH, et al. Interferon receptor signaling pathways regulating PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression. Cell Rep 2017;19:1189–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Diab A, Foca A, Fusil F, et al. Polo-like-kinase 1 is a proviral host factor for hepatitis B virus replication. Hepatology 2017;66:1750–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. All data are available for review.