Abstract

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) data from race/ethnic subgroups remain limited, potentially masking subgroup-level heterogeneity. We evaluated differences in outcomes in Asian American/Pacific Islander (AAPI) and Hispanic/Latino subgroups compared with non-Hispanic White patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

Methods

In the American Heart Association COVID-19 registry including 105 US hospitals, mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events in adults age ≥18 years hospitalized with COVID-19 between March-November 2020 were evaluated. Race/ethnicity groups included AAPI overall and subgroups (Chinese, Asian Indian, Vietnamese, and Pacific Islander), Hispanic/Latino overall and subgroups (Mexican, Puerto Rican), compared with non-Hispanic White (NHW).

Results

Among 13,511 patients, 7% were identified as AAPI (of whom 17% were identified as Chinese, 9% Asian Indian, 8% Pacific Islander, and 7% Vietnamese); 35% as Hispanic (of whom 15% were identified as Mexican and 1% Puerto Rican); and 59% as NHW. Mean [SD] age at hospitalization was lower in Asian Indian (60.4 [17.4] years), Pacific Islander (49.4 [16.7] years), and Mexican patients (57.4 [16.9] years), compared with NHW patients (66.9 [17.3] years, p<0.01). Mean age at death was lower in Mexican (67.7 [15.5] years) compared with NHW patients (75.5 [13.5] years, p<0.01). No differences in odds of mortality or MACE in AAPI or Hispanic patients relative to NHW patients were observed after adjustment for age.

Conclusions

Pacific Islander, Asian Indian, and Mexican patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the AHA registry were significantly younger than NHW patients. COVID-19 infection leading to hospitalization may disproportionately burden some younger AAPI and Hispanic subgroups in the US.

Key Words: COVID-19, Asian, Pacific Islander, Hispanic, disparities

Introduction

Racial/ethnic disparities in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) have been documented in the United States (US).1 Aggregation of individuals into overall race/ethnic categories masks important heterogeneity in health outcomes across race/ethnicity subgroups, but data on COVID-19 outcomes from specific race/ethnic subgroups remain limited.2 Where data on COVID-19 in Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) are available they are frequently presented in a grouped categories. Similarly, data for COVID-19 patterns in Hispanic/Latino subgroups are limited, and Hispanic/Latino individuals are frequently grouped into a single aggregated category.3 Growing evidence suggests that AAPI and Hispanic subgroups may have differential risk for COVID-19, which may be related to differences in sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., occupational exposure, socioeconomic position, language, cultural practices) and comorbidity prevalence.4 To address gaps in understanding COVID-19 hospitalization outcomes in these individuals, we evaluated COVID-19 hospitalization and outcome characteristics in disaggregated AAPI and Hispanic/Latino subgroups in the national American Heart Association (AHA) COVID-19 registry.

Methods

Study Population and Data

The AHA COVID-19 registry is a component of AHA's Get With the Guidelines quality improvement programs provided by the American Heart Association and available to US hospitals, from which race/ethnic differences have been studied.1,5,6 Participating hospitals (N=105) retrospectively abstracted data from patients age ≥18 years hospitalized with COVID-19 between March-November 2020 with admission and discharge dates. We included data from earliest hospitalization record of all patients with complete data for primary measures and outcomes. Registry participation was approved, or review waived, by individual hospital institutional review boards. The registry case report form is available on the AHA website.7 IQVIA (Parsippany, NJ) serves as the data collection and coordination center. De-identified data is available via the AHA's Precision Medicine Platform.7

Variable Definitions

In the American Heart Association COVID-19 Cardiovascular Disease registry, race is categorized as follows: American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian (Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, Other Asian), Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (Native Hawaiian, Guamanian or Chamorro, Samoan, Other Pacific Islander), White, and UTD (unable to determine). Ethnicity is categorized as follows: if Hispanic or Latino: Mexican, Mexican American, Chicano/a; Puerto Rican; Cuban; Another Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish Origin. These data are abstracted from the local electronic health record, and subgroup identification was self-reported.

Based on available sample size, an overall category of AAPI patients, and Chinese, Asian Indian, and Vietnamese subgroups were examined. Samoan, Native Hawaiian, Guamanian or Chamorro, and ‘Other Pacific Islander’ patients were combined into a Pacific Islander subgroup. Filipino, Japanese, Korean, and ‘Other Asian’ patients were included only in the overall AAPI category due to small sample sizes. Hispanic ethnicity patients of all races were also evaluated, from which Mexican and Puerto Rican subgroups were specifically examined. Cuban or ‘Another Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish Origin’ patients were included only in the overall Hispanic/Latino category due to small sample sizes. Patients for whom more than one AAPI or Hispanic/Latino subgroup identification was selected were included only in the respective ‘overall’ category. A non-Hispanic White (NHW) group was evaluated for comparison. The AAPI, Hispanic/Latino, and NHW groups were mutually exclusive. Black patients were not evaluated in this analysis, as characteristics in this group have previously been described.1

Insurance was defined as public (Medicare, Medicaid, VA/CHAMPVA/Tricare), private (HMO/PPO/Other), or other (self-pay, no insurance, not documented). If multiple insurance options including ‘private’ were selected, the patient was categorized as having ‘private’ insurance. Medical history, presentation characteristics, hospitalization treatments and outcomes from the case report form were previously defined.1,7 Consistent with World Health Organization recommendations, obesity was body mass index (BMI) ≥27.5 kg/m2 for AAPI patients, or ≥30 kg/m2 for others.8 CVD history was defined as prior coronary artery bypass graft, myocardial infarction, or percutaneous coronary intervention, history of atrial fibrillation, heart failure, stroke/cerebrovascular accident, or hypertension. The primary outcome was mortality (expired at date of discharge with a recorded death date), the secondary outcome was major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE, defined as death, stroke, new onset heart failure, or myocardial infarction during hospitalization).1

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics and in-hospital treatments and outcomes were reported as mean (standard deviation) or frequency (proportion). Race/ethnicity subgroup-level differences in mean age at hospitalization or death (among decedents) were evaluated with Kruskal-Wallis tests due to small subgroup size, followed by Dunn's test of multiple comparisons with Benjamini-Hochberg stepwise adjustment to control the false discovery rate (type I error of 5%). Mean years of potential life lost (YPLL) per death was the subgroup-level average of the difference between age at death subtracted from 85 years as an “optimal” life expectancy.9 We used sequential multivariable mixed effects logistic regression models to estimate the association of race/ethnicity with outcomes, (unadjusted; model 1 adjusted for age; model 2 further adjusted for sex, insurance, and CVD history). Models included a hospital-specific random intercept to account for within- and between-hospital variability, as we observed non-zero variability in YPLL for non-Hispanic White adults between hospitals. Due to the large number of hospitals, we opted to use a random effects framework, rather than a fixed effect model. Pair-wise comparisons across race/ethnicity subgroups were conducted with Kruskal-Wallis tests with Wilcoxon or Fisher pairwise comparison, employing Benjamini-Hochberg correction to account for multiple comparisons. Analyses were conducted using R 3.5.2.10 The American Heart Association Precision Medicine Platform (https://precision.heart.org/) was used for data analysis.

Results

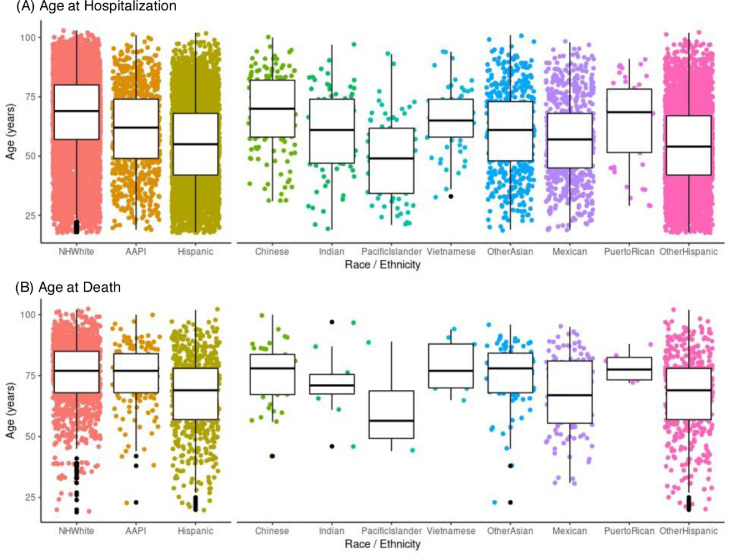

Among 13,511 patients, there were 902 AAPI patients (mean age 61.2 [standard deviation 17.5] years), of whom 149 were identified as Chinese (69.3 [16.0] years), 77 as Asian Indian (60.4 [17.4] years), 74 as Pacific Islander (49.4 [16.7] years), and 61 as Vietnamese (65.4 [13.2] years); 4,683 Hispanic patients (mean age 55.1 [17.5] years) with 681 identified as Mexican (57.4 [16.9] years) and 46 as Puerto Rican (65.1 [17.8] years); and 7,926 NHW patients (66.9 [17.3] years). Clinical, sociodemographic, and medical history characteristics of participants at admission are shown in Table 1. Mean age at hospitalization was lower in AAPI patients overall and Hispanic patients overall compared with NHW patients (p<0.01, Figure, Panel A). Among hospitalized AAPI patients, Asian Indian and Pacific Islander individuals were significantly younger than NHW individuals (p<0.01), and among hospitalized Hispanic patients, and Mexican patients were significantly younger compared with NHW individuals (p<0.01). Among AAPI patients, the highest prevalence of obesity (61%) and diabetes (45%) was in Pacific Islanders, and of hypertension was in Chinese patients (67%). Among the Hispanic subgroups, Puerto Ricans had the highest obesity (44%), diabetes (35%), and hypertension (72%) prevalence. Pairwise comparisons of patient characteristics are detailed in Supplemental Figures 1-5.

Table 1.

Demographic and admission clinical characteristics of hospitalized individuals in the AHA COVID-19 registry, March-December 2020

| NHW | AAPIa | Chinese | Asian Indian | Pacific Islander | Vietnamese | Hispanicb | Mexican | Puerto Rican | |

| N | 7926 | 902 | 149 | 77 | 74 | 61 | 4683 | 681 | 46 |

| Demographics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 66.9 (17.3) | 61.2 (17.5) | 69.3 (16.0) | 60.4 (17.4) | 49.4 (16.7) | 65.4 (13.2) | 55.1 (17.5) | 57.4 (16.9) | 65.1 (17.8) |

| Female | 3588 (45%) | 406 (45%) | 58 (39%) | 30 (39%) | 42 (57%) | 19 (31%) | 1999 (43%) | 279 (41%) | 27 (59%) |

| Insurance | |||||||||

| Private | 2980 (38%) | 360 (40%) | 33 (22%) | 31 (42%) | 31 (42%) | 23 (38%) | 1243 (27%) | 238 (35%) | 14 (30%) |

| Public | 4721 (60%) | 509 (56%) | 112 (75%) | 43 (56%) | 35 (47%) | 35 (57%) | 2930 (63%) | 416 (61%) | 31 (67%) |

| Other | 225 (3%) | 33 (4%) | 4 (3%) | 2 (3%) | 8 (11%) | 3 (5%) | 510 (11%) | 27 (4%) | 1 (2%) |

| Medical History | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obesityc | 3179 (40%) | 186 (21%) | 10 (7%) | 13 (17%) | 45 (61%) | 3 (5%) | 1780 (38%) | 149 (22%) | 20 (44%) |

| Diabetes | 2482 (31%) | 327 (36%) | 52 (35%) | 33 (43%) | 33 (45%) | 22 (36%) | 1541 (33%) | 164 (24%) | 16 (35%) |

| Hypertension | 4973 (63%) | 483 (54%) | 100 (67%) | 41 (53%) | 33 (45%) | 38 (62%) | 2013 (43%) | 200 (29%) | 33 (72%) |

| Smoking/Vaping | 591 (8%) | 46 (5%) | 6 (4%) | 6 (8%) | 2 (3%) | 6 (10%) | 197 (4%) | 10 (2%) | 1 (2%) |

| Prior CAD | 1130 (14%) | 73 (8%) | 14 (9%) | 8 (10%) | 6 (8%) | 7 (12%) | 242 (5%) | 19 (3%) | 7 (15%) |

| Prior HF | 1177 (15%) | 54 (5%) | 6 (4%) | 5 (7%) | 7 (10%) | 3 (5%) | 257 (6%) | 38 (6%) | 8 (17%) |

| Prior CVA | 1009 (13%) | 76 (6%) | 12 (8%) | 12 (16%) | 5 (7%) | 7 (12%) | 295 (11%) | 317 (47%) | 3 (7%) |

| Atrial fib/flutter | 1282 (16%) | 59 (7%) | 21 (14%) | 4 (5%) | 4 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 198 (4%) | 28 (4%) | 6 (13%) |

| Pulmonary disease | 1907 (24%) | 134 (15%) | 20 (13%) | 6 (8%) | 14 (19%) | 8 (13%) | 485 (10%) | 17 (3%) | 12 (26%) |

| PE/DVT | 502 (6%) | 16 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 86 (2%) | 9 (1%) | 1 (2%) |

| Cancer | 1293 (16%) | 79 (9%) | 21 (14%) | 10 (13%) | 4 (5%) | 3 (5%) | 399 (9%) | 199 (30%) | 4 (9%) |

| Presentation Clinical Characteristics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fever | 1147 (15%) | 170 (19%) | 18 (12%) | 13 (17%) | 11 (15%) | 13 (21%) | 1069 (23%) | 75 (11%) | 8 (17%) |

| Tachycardia | 2193 (28%) | 216 (35%) | 51 (34%) | 29 (38%) | 24 (32%) | 15 (25%) | 1181 (39%) | 149 (22%) | 14 (30%) |

| Hypoxia | 2481 (31%) | 282 (31%) | 55 (37%) | 12 (16%) | 32 (43%) | 25 (41%) | 1594 (34%) | 129 (19%) | 8 (17%) |

| CXR/CT infiltrate | 4975 (63%) | 656 (73%) | 114 (77%) | 49 (64%) | 61 (82%) | 48 (79%) | 3232 (69%) | 326 (48%) | 22 (72%) |

| WBC, mean (SD) | 8.1 (4.5) | 7.4 (3.6) | 7.7 (3.9) | 8.1 (4.7) | 7.1 (2.9) | 7.8 (3.2) | 8.2 (4.0) | 8.2 (3.9) | 7.0 (4.0) |

| CRP, mean (SD) | 83 (145) | 62 (70) | 81 (86) | 51 (53) | 46 (47) | 90 (75) | 81 (98) | 37 (62) | 95 (92) |

| D-dimer, mean (SD) | 1790 (3140) | 1780 (3130) | 2960 (5310) | 2600 (3680) | 868 (966) | 1690 (2150) | 1670 (3310) | 2570 (4300) | 1270 (1190) |

AAPI: Asian American/Pacific Islander, PE/DVT: pulmonary embolism/deep vein thrombosis, NHW: non-Hispanic White. Data and percentages for obesity, CXR/CT infiltrate, and laboratory measures account for missing data. Data are presented as frequency (percentage) unless otherwise specified. aAAPI includes Chinese, Indian, Pacific Islander, Vietnamese, and other Asian participants either not further specified or in groups too small to analyze separately. bHispanic includes Mexican, Puerto Rican, and other Hispanic participants either not further specified or in groups too small to analyze separately. cObesity defined as ≥30 kg/m2 in non-Hispanic White and Hispanic patients, ≥27.5 kg/m2 for AAPI patients.

Figure.

Age at hospitalization and age at death among patients in the AHA COVID-19 registry by race/ethnic subgroup

In-hospital treatments and events are detailed in Table 2. In AAPI individuals overall, mean age at death was 75.0 (12.9) years (Figure, Panel B). Within AAPI subgroups, mean age at death ranged from 61.5 (19.8) years in Pacific Islander to 78.6 (10.3) years in Vietnamese patients. In Hispanic individuals overall, mean age at death was 67.3 (15.5) years. Within Hispanic subgroups, mean age at death ranged from 67.7 (15.5) years in Mexican to 78.5 (6.5) years in Puerto Rican patients. Mean age at death was significantly lower in overall Hispanic and Mexican patients, compared with NHW (75.7 [13.5] years, p<0.01). Mean YPLL per death from age 85 years among AAPI subgroups ranged from 8.4 (7.4) years in Vietnamese to 24.5 (17.9) years in Pacific Islander patients. Mean YPLL per death from age 85 years among Hispanic subgroups ranged from 7.0 (5.7) years in Puerto Rican to 18.0 (14.6) years in Mexican patients. Characteristics of patients identified in AAPI and Hispanic subgroups, compared with AAPI and Hispanic patients for whom subgroup ethnicity was not identified, are shown in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

Table 2.

Hospitalization treatments, events, and outcomes in the AHA COVID-19 registry

| NHW | AAPIa | Chinese | Asian Indian | Pacific Islander | Vietnamese | Hispanicb | Mexican | Puerto Rican | |

| N | 7926 | 902 | 149 | 77 | 74 | 61 | 4683 | 681 | 46 |

| Treatments during hospitalization | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU admission | 2646 (33%) | 285 (32%) | 48 (32%) | 23 (30%) | 16 (22%) | 21 (34%) | 1249 (27%) | 170 (25%) | 7 (15%) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1444 (18%) | 191 (21%) | 40 (27%) | 19 (25%) | 7 (10%) | 13 (21%) | 889 (19%) | 114 (17%) | 7 (15%) |

| New RRT | 248 (3%) | 36 (4%) | 12 (8%) | 1 (1%) | 4 (5%) | 2 (3%) | 159 (3%) | 13 (2%) | 3 (7%) |

| Transfusion | 255 (3%) | 30 (3%) | 8 (5%) | 5 (6%) | 3 (4%) | 5 (8%) | 128 (3%) | 10 (2%) | 1 (2%) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 2196 (28%) | 354 (39%) | 86 (58%) | 32 (42%) | 9 (12%) | 15 (25%) | 1952 (42%) | 291 (43%) | 12 (26%) |

| Remdesivir | 1483 (19%) | 138 (15%) | 4 (3%) | 10 (13%) | 22 (30%) | 15 (25%) | 648 (14%) | 90 (13%) | 8 (17%) |

| Tocilizumab | 554 (7%) | 84 (9%) | 10 (7%) | 11 (14%) | 3 (4%) | 10 (16%) | 432 (9%) | 60 (9%) | 3 (7%) |

| Steroids | 3122 (39%) | 286 (32%) | 29 (20%) | 21 (27%) | 24 (46%) | 30 (49%) | 1463 (31%) | 140 (21%) | 9 (20%) |

| Convalescent serum | 751 (10%) | 51 (6%) | 1 (1%) | 7 (9%) | 6 (8%) | 7 (12%) | 292 (6%) | 55 (8%) | 2 (4%) |

| Hospitalization events and outcomes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital mortality | 1294 (16%) | 146 (16%) | 42 (28%) | 11 (14%) | 4 (5%) | 9 (15%) | 628 (13%) | 123 (18%) | 6 (13%) |

| Age at death, mean (SD) |

75.7 (13.5) |

75.0 (12.9) |

76.0 (12.1) | 72.1 (13.1) | 61.5 (19.8) | 78.6 (10.3) |

67.3 (15.5) |

67.7 (15.5) |

78.5 (6.5) |

| YPLL per death, mean (SD)c |

10.8 (11.7) |

11.0 (11.7) |

10.1 (10.7) | 14.2 (10.9) | 24.5 (17.9) | 8.4 (7.5) |

18.3 (14.6) |

18.0 (14.6) |

7.0 (5.7) |

| MACE | 1628 (21%) | 180 (20%) | 50 (34%) | 17 (22%) | 6 (8%) | 12 (20%) | 727 (15%) | 150 (22%) | 7 (15%) |

| Heart failure | 158 (2%) | 16 (2%) | 2 (1%) | 3 (4%) | 2 (3%) | 2 (3%) | 58 (1%) | 19 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Stroke | 124 (2%) | 17 (2%) | 4 (3%) | 2 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (3%) | 42 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| MI | 282 (4%) | 28 (3%) | 9 (6%) | 2 (3%) | 3 (4%) | 2 (3%) | 75 (2%) | 16 (2%) | 2 (4%) |

| Cardiac arrest | 280 (4%) | 21 (4%) | 11 (7%) | 4 (5%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 274 (6%) | 55 (8%) | 2 (4%) |

| Length of stay, days, mean (SD) | 10 (11) | 10 (11) | 11 (11) | 10 (20) | 11 (13) | 10 (10) | 10 (12) | 9 (10) | 10 (10) |

AAPI: Asian American/Pacific Islander, MCS: mechanical circulatory support, MI: myocardial infarction, NHW: non-Hispanic White, RRT: renal replacement therapy, YPLL: years of potential life lost. Data are presented as frequency (percentage) unless otherwise specified. aAAPI includes Chinese, Indian, Pacific Islander, Vietnamese, and other Asian participants either not further specified or in groups too small to analyze separately. bHispanic includes Mexican, Puerto Rican, and other Hispanic participants either not further specified or in groups too small to analyze separately. cYPLL per death indicates mean number of years of potential life lost from age 85 among decedents in each subgroup.

Odds of mortality and MACE in AAPI and Hispanic subgroups relative to NHW patients are show in Table 3. After adjustment for covariates, there was no statistically significant difference in odds of mortality in AAPI or Hispanic subgroups compared with NHW patients. A trend toward higher adjusted odds of mortality was observed in Chinese patients, with odds ratio 1.46 (95% CI 0.94-2.27, p=0.09) relative to NHW patients. After adjustment for covariates, there was no statistically significant difference in odds of MACE in AAPI or Hispanic subgroups compared with NHW patients. A trend toward higher adjusted odds of MACE was observed in Chinese patients, with odds ratio 1.50 (95% CI 0.98-2.27, p=0.06) relative to NHW patients.

Table 3.

Race/ethnicity subgroup differences in COVID-19 in-hospital outcomes in the AHA COVID-19 registry, March-December 2020

| Rate per 1,000c | Unadjusted | Model 1d | Model 2d | ||||

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | ||

| All-Cause Mortality | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHW | 163 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| AAPIa | 162 | 0.86 (0.70 – 1.05) | 0.15 | 1.15 (0.93 – 1.42) | 0.21 | 1.14 (0.91 – 1.41) | 0.25 |

| Chinese | 281 | 1.37 (0.90 – 2.08) | 0.14 | 1.53 (0.99 – 2.38) | 0.06 | 1.46 (0.94 – 2.27) | 0.09 |

| Asian Indian | 143 | 0.84 (0.43 – 1.63) | 0.60 | 1.14 (0.57 – 2.29) | 0.71 | 1.05 (0.52 – 2.11) | 0.90 |

| Pacific Islander | 55 | 0.35 (0.13 – 0.98) | 0.05 | 0.62 (0.22 – 1.76) | 0.37 | 0.62 (0.22 – 1.79) | 0.38 |

| Vietnamese | 148 | 0.73 (0.35 – 1.52) | 0.41 | 0.89 (0.43 – 1.87) | 0.76 | 0.83 (0.39 – 1.76) | 0.63 |

| Hispanicb | 134 | 0.57 (0.50 – 0.65) | <0.01 | 0.98 (0.86 – 1.13) | 0.83 | 0.96 (0.83 – 1.11) | 0.57 |

| Mexican | 180 | 0.69 (0.51 – 0.93) | 0.01 | 1.21 (0.88 – 1.66) | 0.24 | 1.15 (0.84 – 1.57) | 0.40 |

| Puerto Rican | 130 | 0.45 (0.19 – 1.10) | 0.08 | 0.49 (0.20 – 1.24) | 0.13 | 0.49 (0.19 – 1.22) | 0.12 |

| Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHW | 205 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| AAPIa | 200 | 0.88 (0.73 – 1.07) | 0.20 | 1.17 (0.96 – 1.43) | 0.11 | 1.17 (0.96 – 1.42) | 0.12 |

| Chinese | 336 | 1.41 (0.95 – 2.09) | 0.09 | 1.56 (1.03 – 2.37) | 0.04 | 1.50 (0.98 – 2.27) | 0.06 |

| Asian Indian | 221 | 1.15 (0.66 – 2.02) | 0.62 | 1.61 (0.89 – 2.91) | 0.12 | 1.48 (0.81 – 2.70) | 0.20 |

| Pacific Islander | 81 | 0.41 (0.17 – 0.96) | 0.04 | 0.70 (0.29 – 1.69) | 0.43 | 0.72 (0.30 – 1.73) | 0.46 |

| Vietnamese | 197 | 0.80 (0.42 – 1.54) | 0.51 | 0.95 (0.49 – 1.84) | 0.88 | 0.90 (0.46 – 1.76) | 0.76 |

| Hispanicb | 155 | 0.56 (0.50 – 0.64) | <0.01 | 0.95 (0.84 – 1.08) | 0.45 | 0.93 (0.82 – 1.06) | 0.28 |

| Mexican | 220 | 0.72 (0.55 – 0.95) | 0.02 | 1.24 (0.93 – 1.66) | 0.14 | 1.18 (0.88 – 1.57) | 0.28 |

| Puerto Rican | 151 | 0.44 (0.19 – 1.00) | 0.05 | 0.47 (0.20 – 1.11) | 0.08 | 0.46 (0.20 – 1.09) | 0.08 |

AAPI: Asian American/Pacific Islander, CI: confidence interval, CVD: cardiovascular disease, NHW: non-Hispanic White, OR: Odds ratio. aAAPI includes Chinese, Indian, Pacific Islander, Vietnamese, and other Asian participants either not further specified or in groups too small to analyze separately. bHispanic includes Mexican, Puerto Rican, and other Hispanic participants either not further specified or in groups too small to analyze separately. cUnadjusted rate per 1,000 hospitalized patients per subgroup. dModel 1 adjusted for age, Model 2 additionally adjusted for sex, insurance status, and history of CVD (defined as history of coronary artery disease, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, hypertension, or atrial fibrillation). Model 3 (additionally adjusted for diabetes, smoking, and obesity) in overall race/ethnic categories is shown in Supplemental Table 3

Discussion

In a national registry of patients hospitalized for COVID-19, the mean age at hospitalization was significantly lower in Asian Indian (by 6.5 years), Pacific Islander (by 17.5 years), and Mexican (by 9.5 years) patients compared with NHW patients. After adjustment, there were no significant differences in odds of in-hospital mortality or MACE among AAPI and Hispanic subgroups compared with NHW patients, although our findings signaled a trend towards higher adjusted odds of mortality and MACE in Chinese patients. However, relatively small subgroup sizes likely limited power to detect differences for all measures.

These findings extend reports from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that identified higher incidence of COVID-19 infection in Hispanic/Latino, non-Hispanic Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander compared with NHW persons in the US.11 Also, a disproportionately higher proportion of COVID-19 deaths among Hispanic persons younger than age 65 years has been documented.12 However, these reports were limited by use of broad race/ethnicity categories without disaggregation of individual Asian or Hispanic subgroups.

Disaggregation of AAPI and Hispanic patients as demonstrated in this analysis demonstrates heterogeneity in COVID-19-related illness, hospitalization, and outcome characteristics that is likely multifactorial. For instance, the higher burden of risk factors associated with COVID-19 severity may contribute to the younger age of hospitalized patients in certain groups. The Pacific Islander population has a high rates of obesity, and diabetes prevalence is relatively high among Asian Indian and Mexican populations.13, 14, 15, 16 These findings indicate that COVID-19 may affect individuals in these AAPI subgroups at younger ages compared with the NHW population, in part because of early onset of these COVID-19-related cardiovascular risk factors.

Subgroup heterogeneity in COVID-19 hospitalization characteristics may also be related to sociodemographic factors in AAPI and Hispanic subgroups that may contribute to differences in potential exposure to the severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). For instance, certain subgroups have relatively high prevalence of individuals employed in roles with higher risk for SARS-CoV-2 viral exposure, such as in nursing or home health care professions or industries in which working from home is not possible. Household environment and structure may also contribute to differences in exposure. A relatively high frequency of residence in multi-generational households among AAPI and Hispanic/Latino subgroups may increase the risk of potential exposure to SARS-CoV-2 among individuals in these groups.17,18 Such characteristics may contribute to differences in exposure, infection, and hospitalization patterns among subgroups of AAPI and Hispanic populations.

This analysis has several limitations. First, subgroup sample sizes are relatively small. The sample sizes limit robust evaluation of differences and do not exclude the possibility of more modest associations. Additionally, Asian and Hispanic subgroup was not specified in most individuals of these categories. However, this is the only national data source of COVID-19 hospitalization and outcomes that disaggregates broader race/ethnic categories into distinct subgroups, and the Asian and Hispanic patients “not further specified” were not substantially different than those identified in subgroups. Second, only hospitalized patients are described without capture of out-of-hospital events. Third, only patients from participating hospitals were included, which may not represent all US COVID-19 patients. However, the AHA registry is one of the largest national registries with rigorously collected data on COVID-19 patients. Fourth, registry data may be incomplete, nonconsecutive, and independent adjudication of outcomes was not done, which may introduce bias. However, such bias is not expected to disproportionately affect any one race/ethnic subgroup.

In conclusion, in this registry Asian Indian, Pacific Islander, and Mexican patients hospitalized with COVID-19 were significantly younger than NHW patients. Differences in mortality and MACE in AAPI and Hispanic subgroups compared with NHW patients were no longer significant after adjustment for age at hospitalization. These data support growing initiatives by the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology19 and other national organizations to collect and report data according to individual race/ethnicity subgroups in an effort to unmask potential differences in COVID-19 and other health outcomes across diverse communities.

Acknowledgements

The Get With The Guidelines® programs are provided by the American Heart Association. The American Heart Association Precision Medicine Platform (https://precision.heart.org/) was used for data analysis. IQVIA (Parsippany, New Jersey) serves as the data collection and coordination center.

Funding Sources

AHA's suite of Registries is funded by multiple industry sponsors. AHA's COVID-19 CVD egistry is partially supported by The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. This project was supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NIH) grant numbers F32HL149187 and K23HL157766 to NSS and P30AG059988 and R01HL159250 to SSK as well as by the American Heart Association grant number #19TPA34890060 to SSK. The funding sources were not involved in the study design, analysis, interpretation; writing the report; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest or disclosures related to this work.

Footnotes

Author Roles: All authors had access to the data and contributed to writing the manuscript.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajmo.2021.100003.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Rodriguez F, Solomon N, de Lemos JA, et al. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Presentation and Outcomes for Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19: Findings from the American Heart Association's COVID-19 Cardiovascular Disease Registry. Circulation.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Shah NS, Kandula NR. Addressing Asian American Misrepresentation and Underrepresentation in Research. Ethn Dis. 2020;30(3):513–516. doi: 10.18865/ed.30.3.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strully K, Yang TC, Liu H. Regional variation in COVID-19 disparities: connections with immigrant and Latinx communities in U.S. counties. Ann Epidemiol. 2021;53:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.08.016. e52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcello RK, Dolle J, Tariq A, et al. Disaggregating Asian Race Reveals COVID-19 Disparities among Asian Americans at New York City's Public Hospital System. medRxiv. 2020:2020.2011.2023.20233155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Alger HM, Rutan C, JHt Williams, et al. American Heart Association COVID-19 CVD Registry Powered by Get With The Guidelines. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13(8) doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.006967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernandez AF, Fonarow GC, Liang L, et al. Sex and racial differences in the use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators among patients hospitalized with heart failure. JAMA. 2007;298(13):1525–1532. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.13.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Heart Association. COVID-19 CVD Registry. https://www.heart.org/en/professional/quality-improvement/covid-19-cvd-registry. Published 2021. Accessed March 01, 2021.

- 8.W. H. O Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363(9403):157–163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aragon TJ, Lichtensztajn DY, Katcher BS, Reiter R, Katz MH. Calculating expected years of life lost for assessing local ethnic disparities in causes of premature death. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:116. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.R: A language and environment for statistical computing [computer program]. Version 3.5.2. Vienna, Austria R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020.

- 11.Hollis ND, Li W, Van Dyke ME, et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Incidence of SARS-CoV-2 Infection, 22 US States and DC, January 1-October 1, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(5):1477–1481. doi: 10.3201/eid2705.204523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bassett MT, Chen JT, Krieger N. Variation in racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 mortality by age in the United States: A cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2020;17(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hendren NS, de Lemos JA, Ayers C, et al. Association of Body Mass Index and Age With Morbidity and Mortality in Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19: Results From the American Heart Association COVID-19 Cardiovascular Disease Registry. Circulation. 2021;143(2):135–144. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.051936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snowdon W, Malakellis M, Millar L, Swinburn B. Ability of body mass index and waist circumference to identify risk factors for non-communicable disease in the Pacific Islands. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2014;8(1):e36–e45. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Talegawkar SA, Jin Y, Kandula NR, Kanaya AM. Cardiovascular health metrics among South Asian adults in the United States: Prevalence and associations with subclinical atherosclerosis. Prev Med. 2017;96:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng YJ, Kanaya AM, Araneta MRG, et al. Prevalence of Diabetes by Race and Ethnicity in the United States, 2011-2016. JAMA. 2019;322(24):2389–2398. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.19365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang D, Gee GC, Bahiru E, Yang EH, Hsu JJ. Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders in COVID-19: Emerging Disparities Amid Discrimination. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(12):3685–3688. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06264-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodriguez-Diaz CE, Guilamo-Ramos V, Mena L, et al. Risk for COVID-19 infection and death among Latinos in the United States: examining heterogeneity in transmission dynamics. Ann Epidemiol. 2020;52:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.07.007. e42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology . 2021. Public Comment for the 2021 AHA/ACC Key Terms and Definitions for Race and Ethnicity Categorization in Cardiovascular Clinical Research.https://professional.heart.org/en/science-news/public-comment-2021-aha-acc-key-terms-and-definitions-for-race-and-ethnicity-categorization-in-cv-cl PublishedAccessed May 3, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.