Abstract

BACKGROUND

The U.S. health care system is the most expensive in the world, but it lags many other industrialized nations on multiple measures of effectiveness and quality. This poor performance may have played a role in the push to incentivize health care organizations to achieve high performance over a range of domains. Research is needed to understand the determinants of health system performance.

METHODS

In order to identify key attributes of health systems associated with performance, we conducted a literature review. The characteristics we identified were compiled into a web-based rating instrument for use with a technical expert panel (TEP) composed of leaders in health systems and health services research. A modified Delphi process was initiated using three “rounds” to develop group consensus.

RESULTS

The expert panel discussed and rated the importance of nine broad areas in relation to health system performance. Panelists also rated which specific attributes within those domains were predictive of performance. Panelists tended to rate the kind of characteristics used in past research (such as size, ownership and profit status) as only somewhat or not at all important, while rating aspects of culture, leadership and business execution as very important.

CONCLUSION

There is limited empirical evidence or understanding of factors associated with health system performance. We have illustrated the value of using a modified Delphi process to bring experiential evidence to the task. These findings may help researchers refine their data collection efforts, policymakers craft better policies to incentivize high performance, and health leaders build better systems.

INTRODUCTION

The United States spends twice as much per capita on health care than comparably wealthy countries but its population has shorter life expectancy, higher mortality, and heavier disease burden. 1 This dismal profile may have fueled efforts to incentivize U.S. health care providers (such as hospitals and physician organizations) to achieve high performance across a range of domains, including clinical quality, access, cost, and patient experience. 2 Over the past two decades, public and private payers have developed a variety of “pay-for-performance” programs offering providers incentives based on reported measures of quality of care and patient satisfaction. 3 The ratings also give consumers useful benchmarks for comparing health care providers.

Despite increased attention to incentivizing and holding providers accountable for performance, we understand very little about what it takes to be a high-performing health care provider. For example, a recent systematic review found there is no consistent definition of high performance in the literature, and although most studies define high performance across multiple domains, there is significant variation in the number and type of domains used to measure performance. Moreover, there is considerable variation in the number and type of metrics used to represent high performance, with some studies using a very narrow set of metrics and other studies not including specific metrics at all. 4 With little agreement in the field about what constitutes high performance, health care providers are left with limited guidance about optimal trajectories for achieving it. These knowledge gaps are widened by rapid change in the U.S. health care system – in particular the rapid consolidation of hospitals and physician organizations into “health systems” through merger and acquisition. It is challenging to assess the performance of these health systems (in which physicians have aligned with hospitals and other providers within a single ownership or management structure), or to judge whether the trend toward alignment of hospitals and physicians into health systems will improve clinical practice and performance across the U.S..

To understand how the trend toward consolidation of hospitals and physician organizations into health systems might affect the implementation of evidence-based care, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) funded three Centers of Excellence to identify, track, and study health systems, gauging their ability to improve performance by efficiently moving new research evidence into routine clinical practice. 5 As part of this work, we explored what dimensions are used to measure performance and identify high-performing health systems.4 We sought to extend this work by identifying the specific attributes of health systems that are related to high performance and considering the factors that contribute to achieving high performance.

We first conducted a literature review to identify attributes of health systems that are associated with high performance. Given the anticipated limitations of the literature (i.e., that there are very few studies of health systems per se, and that existing studies of hospitals, physician organizations, and other health care organizations might focus on particular attributes because of the availability of data), we convened a Technical Expert Panel (TEP) to supplement the literature. To achieve consensus on attributes strongly associated with high performance, we used the modified Delphi method to draw on panelists’ experience in building, operating, documenting, and studying health systems. Our goal was to identify characteristics of health systems that predict performance outcomes so that researchers could use the attributes identified by the TEP to determine what should be measured, and then to assess empirically whether there is a relationship between these attributes and performance.

METHODS

Literature Review

We conducted a targeted review of the literature using a search of PubMed and Web of Science databases from January 1, 2010 to July 31, 2016 to identify English language articles that reported on characteristics or attributes of health systems in the United States. We also searched the Grey Literature Report published by the New York Academy of Medicine within the same date ranges. Because of the limited number of studies of health systems, we used several combinations of search terms to identify a broader range of health care providers (e.g., health system, hospital, physician group, etc.). (See Table 1).

Table 1:

Literature Review Search Terms

| quality[tiab] OR quality of health care[mj] |

| AND |

| performance[tiab] OR performing[tiab] |

| AND |

| health system* OR healthcare system* OR health care system* OR healthcare organization* OR health care organization* OR microsystem* OR hospital[ti] OR hospitals[ti] OR practice[tiab] OR practices[tiab] OR healthcare delivery system* OR health care delivery system* OR Integrated delivery system* OR Accountable care organization* OR health maintenance organization* OR hmo* OR physician-hospital organization* OR pho[tiab] OR phos[tiab] |

| AND |

| characteristic* OR attribute* OR factor OR factors |

| AND |

| Management OR culture OR cultural OR team OR teams OR teamwork OR workforce OR leader* OR monitor* OR patient-centered OR “patient centered” OR communication OR train OR training OR cohesive* OR team-based OR “care coordination” OR governance OR Investment* OR ownership OR size OR age OR informatics OR “information technology” OR affiliat* OR risk OR risks OR contract OR contracts OR metropolitan OR region* OR rural OR urban OR geograph* |

We included studies of any design that explicitly tested associations of specific attributes of health systems with performance, or that more generally described or highlighted desirable characteristics of health systems with regard to performance. Characteristics could be contextual (such as market profile or patient population); structural (such as age, size, or ownership); organizational (such as leadership); cultural (such as an emphasis on patient safety or teamwork); or programmatic (use of population management programs). We excluded documents that described the performance of government-operated health systems (federal or state), public health systems, and critical access hospitals because the unique structural attributes and performance challenges facing government agencies and safety net providers would require separate analysis.

Our PubMed and World Cat searches identified 4,139 references, our grey literature search identified an additional 62 references, and one additional reference was identified by an expert (Figure 1). After title and abstract screening, 97 articles met our inclusion criteria for full text review; of these, we identified 56 articles that described or tested attributes of health care systems in terms of performance along at least one of four key dimensions: quality (including clinical quality and access); patient satisfaction/patient experience; cost; and patient safety. We reviewed the full text articles and then grouped the attributes we identified through the literature search into eight domains, as follows:

Figure 1:

The literature flow shows how the 56 articles used in the data synthesis were selected.

- Market context

- This domain included attributes such as geographic location, health care market environment, and community characteristics.

- Organizational and structural characteristics

- This domain included attributes such as size, practice ownership, integration (both physician and hospital), patient characteristics, teaching status, ACO risk contracts, financial outlook, and facilities.

- Culture

- This domain included attributes related to some aspect of organizational culture and performance including, but not limited to, quality improvement, collaboration and teamwork, and patient safety.

- Leadership

- This domain included attributes such as board engagement in quality and performance efforts, board membership, strategic planning, and leadership incentives.

- Characteristics of care delivery

- This domain included team-based care/provider teams, clinical decision support, population management strategies, care coordination efforts, prompt and easy access to care, availability of resources for care delivery and improvement, and the use of clinical champions.

- Quality improvement activities and infrastructure

- This domain included attributes such as the use of physician performance monitoring and feedback, staff and provider involvement in QI, publicly reporting performance, having QI leaders, allocating resources specifically to QI, hospital QI activities, and QI communication efforts.

- Health information technology

- This domain included attributes such as information resources or technology, information technology (IT) infrastructure, IT leadership, and using data to drive change.

- Human resources

- This domain included attributes such as staff support, staff engagement, and staff morale.

We summarized findings from the literature review in a notebook that was provided to TEP members as background for their work and grist for discussion.

Technical Expert Panel

To establish the TEP, we selected members from among 35 potential panelists with leadership experience or research expertise in health systems. We sought to balance TEP membership by role (e.g., health system executive vs. researcher), gender, geography, and type /size of health care organization. The final 8-member panel was comprised of c-suite-level leaders of health systems and large, multi-specialty physician organizations, as well as researchers with expertise in economics, business administration, public health, and medicine (See Appendix A for a list of panel members and their bios).

We used a modified Delphi process to identify areas of expert consensus over three rounds (a first individual rating round, a face-to-face group discussion, and a second individual rating round) on a set of high priority attributes that may predict health system performance outcomes. The Delphi method, first developed at the RAND Corporation in the 1950s, has established a standard for using experts and stakeholders to synthesize evidence to arrive at recommendations. 6 The modified Delphi method allows participants to review and interpret the available evidence, particularly in light of methodological weaknesses that may limit the contribution of the evidence to knowledge, make ratings, receive statistical feedback on how their own responses compared to those of others on the panel, participate in a moderated discussion of results, and revise their original answers in light of that discussion. 7 An important strength of the modified Delphi process is that it does not force consensus but instead seeks to identify where agreement exists while being explicit about where disagreement lies. This approach not only serves to parse out and prioritize existing evidence, but also helps to identify areas for further research. 8

The TEP participated in an introductory webinar in which we presented the background and goals of the project, reviewed the initial set of domains and attributes identified in the literature review, and reviewed the rating process. In the first rating round, TEP members received a copy of a notebook with the literature review findings (Appendix B) and were asked to rate each of the attributes identified in the literature review from “Very important” to “Not that important” on a 3-point Likert scale, via a web-based survey (Appendix C).

We then convened an in-person meeting of the TEP for a face-to-face discussion of the first-round ratings. The goal of the discussion was to develop consensus about which domains, and which attributes of the domain, to add, keep, or remove. The panel then deliberated over which of the remaining domains and attributes were the most important for predicting health system performance and, if necessary, further clarified them. This process resulted in a refined list of domains and attributes that the TEP viewed as essential elements in health system performance.

In a second rating round, after the discussion, the panel members were asked to prioritize the health system attributes regarding their importance to data collection on health systems. For each attribute, each member was asked, “Is it a high priority to collect data on [attribute] for differentiating between high performing and low performing health systems?” The response categories included: (1) Yes, it is very important; (2) Yes, it is somewhat important; (3) No, it is not important; or (4) No, it is not relevant. The votes were made in real time and the results presented on the screen using Turning Point polling software and manual “clickers.”

After the meeting, we organized the results into a single table showing the ratings for each attribute within each domain. Those rated as “very important” by at least two-thirds of the panel were highlighted. Additional attributes that were rated as “very important” by at least 50% of the panel were called out for another review. We asked panelists to re-rate this handful of items via web-based survey. No results were changed as a consequence of this final re-rating. The results from the literature review and TEP are presented below.

RESULTS

Literature Review

We identified 56 articles describing or testing attributes of health care providers across eight domains in relation to performance (see Table 2). Below we briefly summarize key findings by domain.

Table 2. Literature Review Summary Table.

This table provides a quick overview of the findings of the literature review on attributes associated with health system performance. Attributes were grouped within domains. The direction of association regarding their effect on performance, and an overall summary of each domain, is provided.

| Domains | Number of articles | Attributes within the Domain | Direction of Association | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational/Structural Characteristics | 26 articles | Size Ownership Organizational integration Patient characteristics Teaching status At-risk contracting Financial outlook Physical facilities |

+/− +/− +/− - +/− +/− +/− +/− |

Organizational/structural characteristics have a highly variable effect on different aspects of performance. A broad range of organizational characteristics have been studied in relation to performance, yet there is limited evidence related to any individual characteristic. |

| Market Context | 10 articles | Geographic location Community characteristics Healthcare environment (e.g., market competition) |

+/− +/− +/− |

Evidence of the relationship between market context and performance is limited and mixed, with negative, positive, and null effects described in the few studies identified. Differences in how variables reflecting the market context are measured warrant caution in interpreting findings and making recommendations. |

| Culture | 20 articles | Learning/change Quality improvement Patient-centered Collaboration/teamwork Accountability Results-driven Innovation/transformation Knowledge-sharing/inclusivity Patient safety Autonomy Shared sense of purpose Focus on social responsibility Culture, unspecified |

+ + + + + + + + + + + + + |

Findings suggest that organizational culture has a consistently positive effect on performance, though the few studies identified are largely descriptive. A more robust understanding of this relationship is also challenged by variation in how culture is measured. |

| Leadership | 23 articles | Board engagement in quality and performance efforts Strategic planning Board membership Leadership incentives Leadership, unspecified |

+ + + + +/− |

Findings largely suggest a positive relationship between organizational leadership and performance, though wide variation in the definition and measurement of leadership, as well as weak study designs, tempers confidence in the direction of this relationship. |

| Care Delivery Characteristics | 22 articles | Use of clinical decision support (including UM) Availability of resources for care delivery/ improvement Patient/provider relationship Use of provider teams Use of population management strategies Care comprehensiveness and care coordination Use of clinical champions Prompt and easy access to care Emerging care models |

+ +/− + + + + +/− + + |

Most identified studies described a positive relationship between care delivery characteristics and performance, though the broad range of variables studied preclude synthesis of findings across studies and limit our ability to make general recommendations about how care delivery characteristics might improve performance. |

| Quality Improvement Activities and Infrastructure | 24 articles | Use of physician performance monitoring and feedback Staff and provider involvement in QI Leadership for QI Publicly reporting performance Resources for QI Scope of hospital QI activities QI communication efforts |

+ +/− + +/− + - + |

Most studies suggest that involvement in QI activities and established QI infrastructure is positively associated with performance, though the evidence base is limited and varied in type. More research is needed to draw conclusions that might be used to inform system-level changes. |

| Health Information Technology | 13 articles | Electronic health records (EHR) Information resources or technology IT infrastructure Use of data and predictive analytics to drive changes IT leadership |

+/− + + + + |

There is mixed evidence that the presence or use of health IT is liked to higher performance. Although health IT has been researched in a variety of ways, relatively few studies investigate its relation to performance itself. In addition, the range of settings in which health IT is assessed hampers our ability to establish firm conclusions regarding its relationship to performance. |

| Human Resources | 15 articles | Staff support Staff engagement Staff morale |

+ + + |

A fairly small evidence base suggests a positive relationship between some aspects of human resources and performance. Further research is necessary to truly understand this relationship. |

Organizational/Structural Characteristics:

We reviewed 26 studies that evaluated how organizational or structural characteristics affected performance. Common structural characteristics that were examined included size, ownership, teaching status, physical facilities, organizational integration (i.e., integration of hospitals with physician organizations), and use of at-risk contracting. Most (18) of the studies identified a mixed relationship between an organizational/structural attribute and performance. However, certain attributes demonstrated a positive impact on performance more than others. Characteristics related to size seemed to correlate to higher patient satisfaction, quality, and performance. This included the number of hospital beds (3), patient volume (3) number of providers (3), and number of practice sites (1). Additionally, two studies found financial performance to be positively associated with increases in quality. Our review also found some evidence suggesting a negative association between the percentage of patients covered by public plans and performance.

Market Characteristics:

Ten articles assessed how characteristics of the market in which a health organization operated (e.g., market share/competition, geographic location, community socio-demographics) affect performance; most (7) reported a mixed relationship. For example, some studies found a positive relationship between performance and geographic location and market competitiveness, others found a negative relationship, and still others found no effect at all.

Culture:

A majority of the included articles (17 out of 20) described a positive relationship between some aspect of organizational culture and performance. Commonly-studied attributes included having a culture of learning or a culture of quality improvement, as well as having a patient-centered culture and a culture of collaboration and teamwork. However, the type of evidence varied; most articles descriptively evaluated the role of culture on performance, though four systematic reviews were found that supported the positive relationship between culture and performance.

Leadership:

Most studies (20 out of 23) described a positive relationship between leadership and performance. General leadership, the type of board membership, having leadership incentives, board engagement in quality and performance efforts, and strategic planning were described as having a positive impact on performance. The remaining studies reported mixed findings and/or no effect.

Characteristics of Care Delivery:

A majority of the included articles (16 out of 22) assessing the relationship of care delivery characteristics and performance described a positive relationship. Having team-based care/provider teams, clinical decision support, population management strategies, care coordination efforts, prompt and easy access to care, and engaging patients in their health care were most frequently mentioned as having a positive impact on performance. Findings pertaining to the availability of resources for care delivery and improvement and the use of clinical champions were mostly positive, a majority of studies reported positive impacts on performance, but a few reported mixed or negative findings and/or were unable to find an association.

Quality Improvement Activities and Infrastructure:

Sixteen out of 24 included studies examining the role of QI activities and infrastructure on performance identified a positive relationship. Use of physician performance monitoring and feedback programs, having QI leadership, and having dedicated resources for QI and a systematic QI communication plan within the organization were all positively associated with performance. However, some studies reported mixed findings regarding staff and provider involvement in QI strategy and mixed findings and/or no association in activities and public reporting of organizational performance. Additionally, studies that investigated the effects of hospital QI involvement on performance found it negatively impacted hospital quality and performance.

Health IT:

Eleven of the 13 included studies found that health IT (e.g., having robust IT infrastructure or dedicated resources for health IT, having continuity in IT leadership, and use of predictive analytics for performance improvement) was linked to higher performance; however, evidence was more mixed than positive on the impact of having an electronic health record (EHR) on performance.

Human Resources:

In general, a majority of the included studies (11 out of 15) examining the role of human resources in performance described a positive relationship between some aspect of human resources and performance. Commonly-studied attributes included staff support – described variably as having sufficient staff, investing in staff education/training, staff capacity building, interdisciplinary staff, and having a strong workforce focus – staff engagement, and staff morale. Investing in staff education and training, as well as staff engagement in improvement efforts, were frequently found to be positively associated with performance.

Our confidence in the robustness of the evidence just described is weakened, however, by methodological concerns. In some domains many papers were qualitative or descriptive; among studies within a domain, studies differed substantially in how they defined and measured attributes; studies within a domain (such as those in the health IT domain) made assessments at various levels of specificity and from different perspectives; and in four of the domains there were mixed findings from studies on individual attributes. All of these factors limited our ability to draw robust conclusions about how to prioritize dimensions and attributes and determine their effect on performance. Although the literature review, by necessity, included studies of a variety of health care providers, the focus of the Center’s work is evaluating the performance of health systems – physicians aligned with hospitals within a single ownership or management structure. For that, the literature provided only a starting point. To identify attributes of health system performance, we would need the input of experts.

Expert Panel

Table 3 reports the final results based on the modified Delphi panel process. The attributes, identified via the literature review and further evaluated by TEP members, are categorized into nine domains (eight domains selected based on the literature and the ninth arrived at during panel deliberations). Once the TEP agreed to a final list of attributes from the first individual rating round and the group discussion, they then rated those attributes from “very important” to “not at all important” in influencing health system implementation and performance. All but one of the attributes (teaching status) was considered to be at least “somewhat important” and therefore we chose a binary presentation of the data (“very important” characteristics of health systems versus “less important” characteristics). Of the 57 attributes, the panel considered more than half (32) to be “very important” to performance.

Table 3. Technical Expert Panel Summary Findings.

Panelists were asked to rate the final list of attributes from “very important” to “not at all important” in influencing health system implementation and performance. The table below provides a binary presentation of the panelist’s groupings of attributes.

| Very Important Characteristics | Less Important Characteristics |

|---|---|

|

| |

|

Organizational/Structural Characteristics

Patient characteristics Risk bearing contracts – assuming full risk Risk bearing contracts – upside/downside risk only |

Organizational/Structural Characteristics

Size Profit status Ownership Structural organizational integration Teaching status Layout and physical facilities |

|

Business Execution

Financial position Ability to manage cost |

Business Execution

Market position Business competencies |

| Market Context |

Market Context

Geographic location Healthcare environment Community characteristics |

|

Culture

Teamwork Patient-centered culture Accountability |

Culture

Innovation Safety/reliability |

|

Leadership

Leadership behaviors Leader engagement in quality and performance efforts Leadership incentives |

Leadership

Board engagement in quality and performance efforts Strategic planning in quality and performance efforts Board composition Mission Leadership intent (priorities) Interorganizational leadership competencies |

|

Care Delivery Characteristics

Availability of resources for care delivery and improvement Effective use of provider teams Use of population management strategies Care comprehensiveness and care coordination |

Care Delivery Characteristics

Use of clinical decision support including utilization management Shared decision making/support Use of clinical champions Prompt and easy access to care Emerging care models |

|

Quality Improvement Activities and Infrastructure

Use of physician performance monitoring and feedback Staff and provider involvement in QI Leadership for QI Resources for QI Trained staff and training for staff |

Quality Improvement Activities and Infrastructure

Publicly reporting performance Scope of hospital QI activities QI communication efforts |

|

Health Information Technology

Electronic health records (EHR) and functions Use of data and predictive analytics to drive changes IT leadership and clinical informatics |

Health Information Technology

IT infrastructure IT leadership (systems and governance) |

|

Human Resources

Staff engagement Staff quality |

Human Resources

Staff support Staff morale HR bundle |

Among organizational/structural characteristics, the identified attributes tended to be factors that may affect performance in terms of cost – specifically whether the organization has taken on risk bearing contracts (i.e., assuming full risk or taking downside risk in a shared savings contract). They also included attributes associated with patient characteristics, which panelists viewed as playing a critical role in achieving successful patient outcomes. The TEP ranked attributes related to organizational characteristics such as size, profit status, teaching status, and ownership as less important.

Panelists argued for adding a 9th domain, which we came to call “business execution,” and which they felt was an area overlooked by the literature review (and generally overlooked by health services researchers). They assigned four attributes to this domain. Of these, panelists considered “financial position” and “ability to manage cost” very important, while a system’s actual market position and other business competencies (such as regulatory compliance) were considered less important. In discussion, TEP members noted that the ability to manage a business including assuming and managing risk was critical for health systems to achieve high performance.

A few panelists argued that the competitiveness of the health care market and state policy context were important; however, opinion on this issue was not reflected in the final vote. None of the market context characteristics (geographic, environmental or community characteristics) was determined to be very important to predicting performance.

Panelists stated that while culture and leadership were difficult domains for researchers to measure, they were very important characteristics of a health system. One panelist suggested that it was wrong to think of an organization as having a single culture but rather that systems are “multi-cultural” with a “core and peripheral culture.” Other panelists agreed with this suggestion; ultimately TEP members condensed the thirteen attributes related to culture to five. Three of these attributes – teamwork, accountability and patient-centeredness – were rated as very important; a culture of safety and reliability was seen as somewhat less important. Some panelists thought that a culture of innovation within a health system would assume more importance over time.

Leadership behaviors, engagement in quality and performance efforts, as well as leadership incentives were noted as very important to high performance; however, board composition and engagement, strategic planning, and “mission” were prioritized less. In the case of mission, this rating reflected less a belief that mission is not vital to performance, and more a view that the content of “mission statements” does not necessarily reflect real differences across organizations. Shared core values was viewed as critical. However, panelists noted, culture takes a long time to change. Premature heightened expectations are common and unhelpful in supporting high performance.

Care delivery characteristics such as availability of resources for care delivery and improvement, effective use of provider teams, and use of population management strategies were rated as highly important – with resource availability related to a health system’s business execution. Attributes such as the use of clinical champions or emerging care models were judged as lower priority.

All the panelists rated quality improvement activities and infrastructure as very important. Performance monitoring and feedback, staff and provider involvement, resources, leadership, and training were seen as priorities for quality improvement; communication efforts, public reporting, and scope of QI activities less so. Panelists observed that making QI an organizational imperative means that practitioners can be assured that clinical improvement is a core value. Internal reporting was viewed as more important than public reporting, if managed carefully. Engaging teams in QI was critical, rather than having an external QI program team.

The high priority assigned to staff engagement and involvement in QI appeared to resonate in other domains, including human resources, where panelists viewed engagement and staff quality as very important. However, while resources seemed to be important in most other areas, support for human resource staff, and staff morale were considered a lower priority. One panelist said he viewed staff morale as a performance measure (e.g., staff satisfaction) and not as an attribute of a system.

Most of the attributes within the health information technology (IT) domain were rated as very important, underscoring the value these experts assigned to IT and reflecting their view that this domain is crucial to high performing health systems. One panelist lamented that, for the massive investments that have been made in HIT, it’s remarkable how little is known about it. The literature yielded on only 7 relevant studies, a number that was “depressingly low.”

During discussion, panelists suggested that while data are important, it is “actionable data” or usable data that are critical. They suggested that producing usable data depends primarily on leadership in clinical informatics and physician involvement in IT. Using data to support change is core to success, one panelist observed.

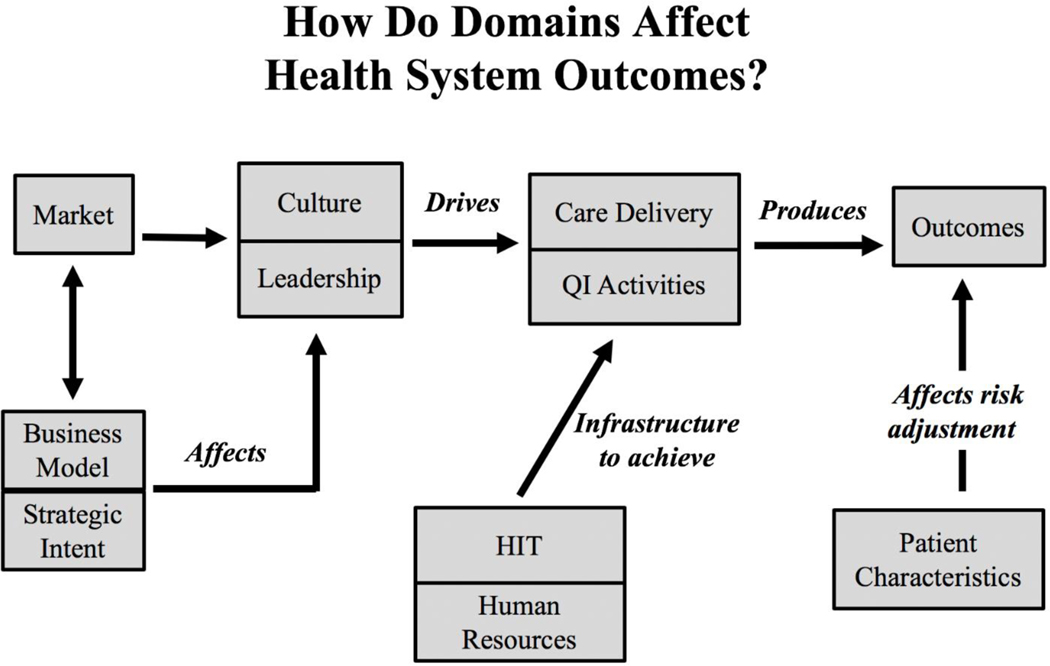

The panelists constructed a logic model associating the various domains and describing how they interact to affect performance (Figure 2). Based on their experience, panelists saw the market as influencing the business model and strategic intent of a health system. The market also impacts the culture and leadership of a health system, which is affected by the business model and strategic intent. One panelist observed that high performance cannot occur without leadership at the top. While culture and leadership ultimately drive care delivery and quality improvement activities, panelists felt that health IT and a system’s human resource infrastructure were also necessary to achieve desired patient care delivery and quality. Improvements in care delivery and quality assurance help to produce better patient outcomes; but members noted that these outcomes are ultimately influenced by patient characteristics.

Figure 2:

Shown here are the interrelationships among the various domains that affect health system performance. QI, quality improvement; HIT, health information technology.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge no other study has attempted to empirically identify health system characteristics that predict a system’s performance using an expert panel composed of leaders who design, build, and operate health systems. Given the lack of agreement on what constitutes a high-performing health system, and the little that is known about what attributes are associated with high performance, our findings are a first attempt to identify attributes that enable a health system to achieve high performance and to prioritize attributes that researchers should consider in designing studies on the performance of health systems. Some of these attributes are available in survey and other secondary data (such as market context, size, ownership and EHR functions), but other critical attributes (such as those related to business execution, culture and leadership) that are equally if not more important to explaining high performance require primary data collection – and the development of new data collection tools.

Although the literature linking specific attributes to health system performance is weak, the expert panel’s work provides real-world evidence about the attributes of health systems that drive high performance, notably the importance of infrastructure (such as health information technology) and the use of data to drive changes in health care delivery. Panelists supported the link between various attributes and performance – although there were points of difference between the literature review and the panel’s conclusions.

For example, several studies from the literature review identified the positive relationship between health IT and performance, and a few demonstrated the use of data and information resources to drive change and contribute positively to performance and quality improvement. 9–11 However, quantitative studies on the use of EHR (and EHR functions) that panelists ranked as very important yielded mixed results on linking EHR capabilities and performance. 12–14

Panelists also identified culture and leadership as important, noting that these domains are often difficult for researchers to measure systematically. A number of studies in our literature review identified a positive relationship between some aspect of organizational culture and performance. Having a culture of quality improvement, a culture of “patient-centeredness,” and a culture of collaboration and teamwork, were most frequently cited as having a positive impact on performance. 15–19 In addition, studies on an organization’s culture of collaboration and teamwork have all reported positive associations between collegiality, team building, and high performance, strongly suggesting that culture has a profound impact on performance. 11, 15, 19, 20 Our panel agreed but also highlighted accountability as a key cultural variable closely related to performance.

Leadership was another area that panelists viewed as critical to a high performing health system. Consistent with this assertion, several studies suggest that general leadership, board engagement, and leadership incentives positively impact performance. 16, 19, 21–23 Leadership was generally favorably linked to high performance of hospitals and health systems and was described as key to improving performance and successfully implementing interventions. 16, 22, 24, 25 In addition, within the literature, the extent of top level management’s involvement in quality improvement efforts also helped to predict the success of quality improvement efforts, highlighting that leadership has an important role in improving quality. 15, 26

Business characteristics such as the ability to manage cost, financial position, and managerial competency were not identified in our literature review, but the panelists viewed them as important attributes of high performing systems. As panelists noted, these attributes are often overlooked by researchers or are considered to be associated with profit-making at the expense of service provision. This observation illustrates the need for health services researchers to think broadly to integrate business and management attributes into their assessment of high performing health systems. This observation may have been one of the most important contributions of the health system leaders on our panel.

Panel members also created a logic model after discussing the key domains of high performance (Figure 2). The logic model provides a visual representation of how each domain impacts others to produce patient outcomes. Prior studies have constructed similar models, however these models have focused on factors that impact quality improvement within a system – such as improvements in quality of care or patient safety – rather than looking at the broader external and internal factors that influence systems overall to improve performance.27, 28 This logic model also differs in that it was created based on panel members’ own experience and insight into performance of health systems, using domains that were agreed upon after careful discussion. Thus, this model provides the unique perspective of those who drive health system performance, which may differ from other existing models.

Limitations

Our literature review was extensive, and we attempted to include all attributes that might be important descriptors of health systems or predictive of their performance. However, our review focused on U.S. literature and therefore our findings may only be applicable to the United States. Additionally, we may have missed some attributes and as a result they were omitted from the panel discussion. In addition, as noted by several of our panelists, the business management literature was not included in our initial search or in our list of domains; and thus, we may have excluded some potentially important attributes related to business execution. This problem was addressed in the expert panel during the face-to-face meeting. Furthermore, although the panel provided an important experiential dimension to the study, we understand that not all experiences are the same, and another set of experts might have prioritized a different set of domains and attributes. Moreover, the logic model created by panel members provides their interpretation of the way in which these domains affect one another and drive performance. We understand that there may be other ways one could interpret the impact of these domains. This logic model offers a starting point for discussion that others might use and that future studies might improve upon.

CONCLUSION

The strengths of the study include its use of a modified Delphi method which is the established standard for identifying areas of expert consensus when solid empirical evidence is lacking. The three-round approach (comprising two individual rating rounds separated by a face-to-face meeting to discuss results) provided a forum for panelists to build consensus around a list of domains and attributes. The expert panel brought a rich real-world dimension to the inquiry. Drawing on their extensive knowledge and experience in operating and studying health systems, the panelists expanded and revised the original list of attributes and domains derived from the literature review. The experience of the panelists both affirmed and expanded on what was found in the literature, providing face validity to the assessment.

This study is part of an ongoing effort to discover how and why some health systems in the U.S. are high performing and others are not. We believe there is value to bringing experiential evidence into the inquiry, not the least because empirical studies may focus on particular attributes because of the availability of data (or of existing measures and metrics) rather than because a specific attribute is predictive of performance. The list of priority attributes we developed with the TEP may help health services researchers refine their research questions and data collection efforts so that they may better differentiate high performers based on these characteristics. In addition, we hope that experientially informed research such as ours can inform policymakers as they attempt to craft better policies to incentivize high performance and will support health leaders in their efforts to build better health systems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the work of the Technical Expert Panel including (in alphabetical order) Gloria Bazzoli, Howard Beckman, Mark Briesacher, R. Adams Dudley, Terry Hill, George Isham, Rob Nordgren, Michelle Schreiber, and Steve Shortell. We also acknowledge our colleagues at RAND, Patty Smith and Lynn Polite, for their administrative support.

Funding Sources

This work was supported through the RAND Center of Excellence on Health System Performance, which is funded through a cooperative agreement (1U19HS024067-01) between the RAND Corporation and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content and opinions expressed in this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the Agency or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to report.

References:

- 1.Schneider EC and Squires D, From Last to First - Could the U.S. Health Care System Become the Best in the World? N Engl J Med, 2017. 377(10): p. 901–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker A, Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. BMJ 2001. 323.7322: p. 1192.11358756 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Damberg CL, et al. , Taking stock of pay-for-performance: a candid assessment from the front lines. Health Aff (Millwood), 2009. 28(2): p. 517–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahluwalia SC, et al. , What Defines a High-Performing Health Care Delivery System: A Systematic Review. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 2017. 43(9): p. 450–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.AHRQ. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Fact Sheet: Comparative Health System Performance Initiative. 2016; Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/chsp/chsp-fact-sheet-0717.pdf.

- 6.Brown BB, Delphi process: A methodology used for the elicitation of opinions of experts. 1968, RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khodyakov D, et al. , Acceptability of an online modified Delphi panel approach for developing health services performance measures: results from 3 panels on arthritis research. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 2017. 23(2): p. 354–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shekelle P, The appropriateness method. Medical Decision Making, 2004. 24(2): p. 228–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barro WM, et al., Critical success factors for performance improvement programs. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf, 2005. 31(4): p. 220–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hockey PM and Bates DW, Physicians’ identification of factors associated with quality in high- and low-performing hospitals. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf, 2010. 36(5): p. 217–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Aunno T, et al. , Factors That Distinguish High-Performing Accountable Care Organizations in the Medicare Shared Savings Program. Health Serv Res, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albright BB, et al. , Preventive Care Quality of Medicare Accountable Care Organizations: Associations of Organizational Characteristics With Performance. Med Care, 2016. 54(3): p. 326–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Appari A, Johnson EM, and Anthony DL, Information technology and hospital patient safety: a cross-sectional study of US acute care hospitals. Am J Manag Care, 2014. 20(11 Spec No. 17): p. eSP39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Damberg CL, et al. , Relationship between quality improvement processes and clinical performance. Am J Manag Care, 2010. 16(8): p. 601–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dugan DP, et al. , The relationship between organizational culture and practice systems in primary care. J Ambul Care Manage, 2011. 34(1): p. 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan HC, et al. , The influence of context on quality improvement success in health care: a systematic review of the literature. Milbank Q, 2010. 88(4): p. 500–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Girotra S, Cram P, and Popescu I, Patient satisfaction at America’s lowest performing hospitals. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes, 2012. 5(3): p. 365–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foster TC, et al. , Using a Malcolm Baldrige framework to understand high-performing clinical microsystems. Qual Saf Health Care, 2007. 16(5): p. 334–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keroack MA, et al. , Organizational factors associated with high performance in quality and safety in academic medical centers. Acad Med, 2007. 82(12): p. 1178–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Etchegaray JM and Thomas EJ, Engaging Employees: The Importance of High-Performance Work Systems for Patient Safety. J Patient Saf, 2015. 11(4): p. 221–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parand A, et al. , The role of hospital managers in quality and patient safety: a systematic review. BMJ Open, 2014. 4(9): p. e005055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor N, et al. , High performing hospitals: a qualitative systematic review of associated factors and practical strategies for improvement. BMC Health Serv Res, 2015. 15: p. 244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Werner RM, et al. , The effect of pay-for-performance in hospitals: lessons for quality improvement. Health Aff (Millwood), 2011. 30(4): p. 690–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clay-William R, et al., Do large-scale hospital- and system-wide interventions improve patient outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res, 2014. 14: p. 369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donahue KE, et al. , Facilitators of transforming primary care: a look under the hood at practice leadership. Ann Fam Med, 2013. 11 Suppl 1: p. S27–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parker VA, et al. , Implementing quality improvement in hospitals: the role of leadership and culture. Am J Med Qual, 1999. 14(1): p. 64–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaplan HC, et al. , The Model for Understanding Success in Quality (MUSIQ): building a theory of context in healthcare quality improvement. Bmj Quality & Safety, 2012. 21(1): p. 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McAlearney AS, et al. , High-performance work systems in health care management, Part 2: Qualitative evidence from five case studies. Health Care Management Review, 2011. 36(3): p. 214–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.