Abstract

Background

Professional identity formation (PIF) in medical students is a multifactorial phenomenon, shaped by ways that clinical and non-clinical experiences, expectations and environmental factors merge with individual values, beliefs and obligations. The relationship between students’ evolving professional identity and self-identity or personhood remains ill-defined, making it challenging for medical schools to support PIF systematically and strategically. Primarily, to capture prevailing literature on PIF in medical school education, and secondarily, to ascertain how PIF influences on medical students may be viewed through the lens of the ring theory of personhood (RToP) and to identify ways that medical schools support PIF.

Methods

A systematic scoping review was conducted using the systematic evidence-based approach. Articles published between 1 January 2000 and 1 July 2020 related to PIF in medical students were searched using PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, ERIC and Scopus. Articles of all study designs (quantitative and qualitative), published or translated into English, were included. Concurrent thematic and directed content analyses were used to evaluate the data.

Results

A total of 10443 abstracts were identified, 272 full-text articles evaluated, and 76 articles included. Thematic and directed content analyses revealed similar themes and categories as follows: characteristics of PIF in relation to professionalism, role of socialization in PIF, PIF enablers and barriers, and medical school approaches to supporting PIF.

Discussion

PIF involves iterative construction, deconstruction and inculcation of professional beliefs, values and behaviours into a pre-existent identity. Through the lens of RToP, factors were elucidated that promote or hinder students’ identity development on individual, relational or societal levels. If inadequately or inappropriately supported, enabling factors become barriers to PIF. Medical schools employ an all-encompassing approach to support PIF, illuminating the need for distinct and deliberate longitudinal monitoring and mentoring to foster students’ balanced integration of personal and professional identities over time.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-021-07024-9.

KEY WORDS: professional identity, professional identity formation, PIF, personhood, ring theory of personhood

INTRODUCTION

Professional identity in medicine refers to one’s “interpretation of what being a good doctor means and the manner in which he or she should behave” 1. Holden et al. 2 describe professional identity formation (PIF) “as the foundational process one experiences during the transformation from lay person to physician”. Growing data suggest that PIF is heavily influenced by how medical students evaluate their professional roles and responsibilities in light of fluid circumstances and clinical experiences. This developmental process is shaped by sociocultural, familial, academic, moral, religious and gender-based roles, values, beliefs and obligations 3–6. The complexity herein underlines the challenge that medical schools face in viewing and reviewing their approaches to fostering PIF 7–10.

Identity is a manifestation of qualities, conditions, beliefs, values and ideals that humans possess and regard with importance. While core components remain foundational and enduring, identity exists in a perpetual state of flux with elements taking on different forms and priorities. Moss et al.11 posit that professional identity “is the integration of the professional self and the personal self”. This suggests a connection between PIF in medical school and the students’ own concept of identity or personhood.

Personhood has been conceived in a plethora of ways. While Buron’s 12 levels of personhood considers individual, biological and sociological concepts, Dennett 13 underscores the importance of communicative and cognitive faculties. A number of these concepts incorporate Lockean 14 and Kantian’s 15 formulations that necessitate the presence of consciousness, rationality, self-awareness, intelligence, moral value, attainment of legal status 16 and personal, enduring interests 17–20. What these static frameworks do not consider is the dynamic influence of one’s changing beliefs, attitudes and perceptions on decision-making 21–23. Similarly, existing concepts of PIF in medical students do not holistically acknowledge the evolving person behind the budding professional.

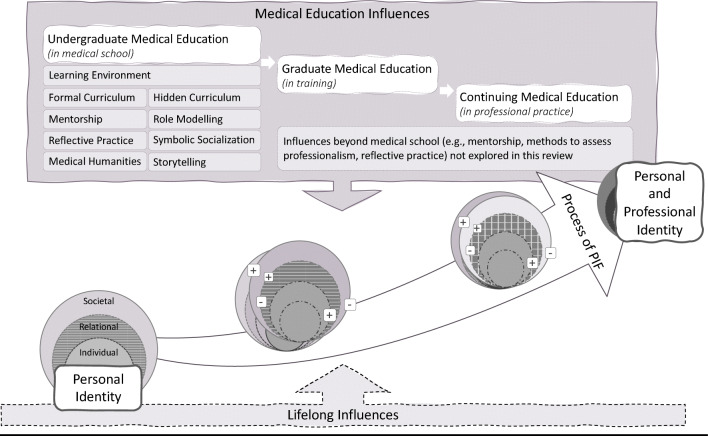

To explore these gaps, we adopted Krishna and Alsuwaigh’s ring theory of personhood (RToP) 24,25, which characterizes personhood as four interconnected rings — the Innate, Individual, Relational and Societal (Figure 1). This framework considers the evolving nature of personhood and various sources of influence that inform one’s self-concept of identity, i.e. what makes us who we are 26,27. The Innate Ring represents qualities that remain steadfast such as an individual’s genetic makeup and the family, society, culture, religion, race and gender into which an individual is born. Though some features may change, these impact an individual’s development and often form the basis of who they are as a person. The Individual Ring represents one’s conscious function and ability to communicate and display emotions. Beliefs and values within this ring are informed by its specific contents. A religious individual, for example, holds beliefs, values and principles associated with their religious stance. The more strongly the individual upholds these, the more it impacts their thoughts, decisions and actions. This highlights the entwined nature of various aspects of personhood and the role of the Individual Ring in shaping identity. The Relational Ring depicts the close personal ties that one shares with those deemed important. The Societal Ring houses more distant relationships as well as social expectations, cultural norms, professional standards and religious obligations placed upon the individual. These include codes of conduct and practice expected of the person by virtue of their membership within society.

Figure 1.

The four rings of personhood in RToP

One’s self-concept of identity can thus influence, exist as a part of, and encapsulate an evolving professional identity. To explore this concept in the medical school context, we aimed to capture the various elements of PIF through a scoping review, and used the RToP as an organizing framework to explore how fluid circumstances related to professional identity development may affect a medical student’s personhood.

METHODS

We used a systematic scoping review (SSR) to map available data on PIF in prevailing undergraduate medical education literature and to identify information related to key characteristics of PIF within this context 28,29. To overcome the absence of a consistent approach to conducting scoping reviews 30, a 16-member research team applied Krishna’s systematic evidence-based approach (SEBA) 31–33. The six-stage structured process (Figure 2) provides a reproducible and transparent means of reviewing the search process, and the manner in which the data was accrued, analyzed and used to inform the conclusions drawn within the SSR.

Figure 2.

A schematic of the steps involved in systematic evidence-based approach (SEBA). Abbreviations: TA, thematic analysis; DCA, directed content analysis; BEME, Best Evidence Medical Education; STORIES, Structured approach to the Reporting In healthcare education of Evidence Synthesis

SEBA’s constructivist perspective allowed for capture of psychosocial, cultural and historical influences that underpin individual concepts of PIF, and its relativist lens enabled a holistic picture by considering various perspectives through data collected from quantitative, qualitative and knowledge synthesis articles.

Each stage of SEBA additionally involved input from an expert team that guided the practical approach to the project, while independently reviewing and accounting for data collection, analysis and synthesis. The expert team comprised a medical librarian from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (YLLSoM) at the National University of Singapore (NUS), and educational experts and clinicians from the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS), the Palliative Care Institute Liverpool, YLLSoM and Duke-NUS Medical School.

Stage 1: Systematic Approach

-

A.

Determining the background of review

The research and expert teams reviewed the overall objectives of the SSR, and determined the population, context and concept to be evaluated. This decision was guided by the preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 checklist 34,35 (see Appendix 1).

-

B.

Identifying research questions and Inclusion Criteria

Teams agreed for the primary research question to be “what is known of PIF in medical school education?” To ascertain the wider impact of PIF on the self-concept of medical students, these secondary research questions were identified: “how may influences of PIF be viewed through the RTOP lens?” and “how do medical schools support PIF?”

A PICOS format framed the research process 36,37 and may be found in Appendix 2. Guided by the expert team and prevailing descriptions of PIF, the research team developed a search strategy for PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, ERIC and Scopus databases. Independent searches were carried out for articles published between 1 January 2000 and 1 July 2020. The full PubMed search strategy may be found in Appendix 3. All research methodologies (quantitative and qualitative) in articles published or translated into English were included.

-

III.

Selecting included articles

The sixteen members of the research team independently reviewed the identified titles and abstracts, created lists of articles to be included, discussed these online, and reached consensus using Sandelowski and Barroso’s 38 “negotiated consensual validation” approach. Acknowledging limitations of the search terms, the members also performed reference snowballing. The PRISMA flow diagram can be found in Appendix 4.

-

IV.

Assessing quality of articles

Eight research team members individually appraised the quality of the quantitative and qualitative studies using the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI) 39 and Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ) 40. This allowed us to evaluate the methodology employed in the included articles, aid readers and reviewers in appraising the extent to which we reported the data, the weight we afforded the data in our analysis 41 and assist decision-makers in understanding the transferability of the findings 42. The analysis of 43 of 76 included articles amenable to quality appraisals may be found in Appendix 5.

Stage 2: Split Approach

To increase the reliability and transparency of the analysis, the Split Approach was adopted 43,44. Seven members of the research team independently analyzed the data using Braun and Clarke’s 45 approach to thematic analysis. Concurrently, nine members of the research team employed Hsieh and Shannon’s46 directed content analysis to independently analyze the data. This concurrent analysis aimed to reduce omission of new findings or negative reports and enable review of data from different perspectives. The reviewers within each sub-team achieved consensus on their analyses before comparing with the other two.

-

A.

Thematic analysis

In the absence of rigorous definitions of PIF, seven members of the research team adopted Braun and Clarke’s approach to identifying key themes across different learning settings and learner/instructor populations 47,48. This allowed for analysis of data derived from quantitative, qualitative and mixed methodologies 49,50. This sub-team independently reviewed the included articles, constructed codes from surface meaning of the text and collated these into a code book, which was used to code and analyze the rest of the articles in an iterative process. New codes were associated with prior codes and concepts 51,52. An inductive approach allowed us to identify codes and themes from the raw data without using existing frameworks or preconceived notions as to how the data should be organized. The sub-team discussed their independent analyses in online and face-to-face meetings and used “negotiated consensual validation” to derive the final themes.

-

B.

Directed content analysis

Nine members of the research team independently employed Hsieh and Shannon’s approach to directed content analysis. This involved “identifying and operationalizing a priori coding categories” by classifying text of similar meaning into categories drawn from prevailing theories 46. Four members first used deductive category application 53 to extract codes and categories from Cruess et al.’s54 article, “A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialization of medical students and residents: A guide for medical educators”.

Separately, to ensure adequate focus on the RToP domains, five members used Krishna and Alsuwaigh’s24 article, “Understanding the fluid nature of personhood – the ring theory of personhood” to draw the categories to be used as part of Hsieh and Shannon’s approach to directed content analysis. This was to evaluate the prevailing data through the lens of RToP and to answer the secondary research question on how PIF influences may be viewed through the lens of RToP. A code book was developed and individual findings were discussed through online and face-to-face meetings. Differences in codes were resolved until consensus was achieved on a final list of categories.

Stage 3: Jigsaw Perspective

The Jigsaw Perspective hinges on Moss and Haertel’s55 suggestion that complementary qualitative data should be reviewed together to give “a richer, more nuanced understanding of a given phenomenon”. It considers each finding as a piece of jigsaw that combined with appropriate or complementary pieces, portrays a more complete picture. The research team thus identified and combined significant overlaps and similarities between themes and categories to gather a holistic picture of available data on PIF and RToP.

Stage 4: Funnelling

Six members of the research team further summarized and tabulated the full-text articles included in the review according to Wong et al.’s56 RAMESES publication standards and Popay et al.’s57 guide to conducting narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. This was to verify that the jigsaw pieces appropriately reflected key insights from the prevailing data, ensuring that critical information was not lost.

To assist with this process, the team adopted Phases 3 to 6 of France et al.’s58 adaptation of Noblit and Hare’s 59 seven phases of meta-ethnography to study the included articles 60. In line with Phase 3, the study aim, key findings and insights were included in the tabulated summaries. In line with Phase 4, the team juxtaposed the themes and categories by grouping them, guided by the commensurate focus of the included articles from which the themes and categories were drawn from. The homogeneity of the themes and categories allowed the adoption of reciprocal translation and latterly the mapping of the various themes/categories in Phase 6. These themes/categories, which form the basis of what Noblit and Hare call “the line of argument”, are presented in the “RESULTS” section. The tabulated summaries are found in Appendix 6.

Stage 5: Analysing Data from Research and Non-research-based Sources

As the research team iteratively streamlined and organized the data, the expert team was critical in overseeing and guiding this process through numerous discussions. In so doing, the expert team considered that data from grey literature that was not quality-assessed or evidence-based could bias the discussion. As such, the research team thematically analyzed data from grey literature and non-research-based pieces such as letters, opinion and perspective pieces, commentaries and editorials extracted from the bibliographic databases. When these themes were compared with those from peer-reviewed data, no differences were identified.

Stage 6: SSR Synthesis

The Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) Collaboration guide 49 and the STORIES (Structured approach to the Reporting In healthcare education of Evidence Synthesis) statement 61 were adopted to guide the SSR narrative.

RESULTS

A total of 10443 titles and abstracts were reviewed and a final 76 full-text articles included. Our thematic and directed content analyses yielded similar themes and categories. Following the Jigsaw Perspective and Funnelling stages, we categorized these themes as follows: characteristics of PIF in relation to professionalism (in medicine), role of socialization in PIF, enablers and barriers to PIF, and medical school approaches to supporting PIF.

PIF characteristics in relation to professionalism

PIF and professionalism are mutually reinforcing, each influencing the other. PIF is a necessary foundation to professionalism 62 while also contingent upon it. Professionalism in medicine is a process of adopting a shared belief system that focuses on improving the health of patients 63,64 by attaining technical and cognitive clinical competencies 65–69, meeting high ethical and moral standards 64,67–71, and displaying behaviours consistent with professional principles and values 9,64,69,72–74. To exemplify the profession’s expectations as a lifelong ideal, students must be able to reconcile their personal and professional identities.

Critical to the formation of professional identity, on the other hand, is a commitment to the profession 62,72,75–77. When this commitment deepens through an ongoing process of adapting, internalizing and assimilating professional traits into intrinsic characteristics (virtue-based professionalism) and observable actions (behaviour-based professionalism) 2,5,6,68,69,76,78–80, a new integrated identity takes shape 2,5,6,68,69,76,78–80. Factors that influence professional behaviour include mentorship and role-modeling 81,82, prevailing codes of conduct 67 and social and cultural concepts of the “good physician” 82. Manifesting such professional values and behaviours can further foster professional identity 2,5,64,75–77,80,83, through which medical students identify as a member of the profession 67,84,85 and aim to embody its roles and responsibilities 2,6,8,9,62,63,65,66,68,69,72–75,80,83,85–96.

Affirming the importance of professional attitudes, ethical conduct, reflective practice and supportive relationships, PIF thus captures the nuanced process by which a medical student personally and professionally transforms into a doctor 2,97.

-

2.

Socialization in PIF

Socialization is the process of becoming a part of the medical community 7,72,98 and developing a sense of professional identity through shared knowledge and skills 72,98. This process is individualized, non-linear and heavily influenced by formal 5,98,99, informal and hidden curricula 4,72,98. As students move from early peripheral involvement 8,72,100 to assuming a more central role in the community of practice with increasing seniority 69,72,98,101, intrinsic characteristics, values, beliefs, behaviours and biases are re-examined 62,63,69,80,93–96, refined 9,73,100, re-aligned and integrated. Socialization is facilitated by formal ceremonies and seminal experiences such as White Coat Ceremony and cadaveric dissections 62,69, and promoted when experiencing patient care 2,6,62,69,76,83,102, managing clinical responsibilities 8,72,100, working long hours 5 and reflecting upon experiences and clinical identities 5,69,71,83,96,99. This evolving process, which continues along the continuum of medical education, sees individuals advance progressively from “doing” toward a way of “being” 69.

-

3.

PIF influencing factors

A series of influencing factors promote or hinder professional identity formation as enablers or barriers that are intrinsic or extrinsic to the student. These are presented in Table 1 through the person-centric lens of RToP and its Individual, Relational and Societal Rings. Limited data on the Innate Ring prevented further evaluation of the impact of PIF on this aspect.

Table 1.

Enablers and barriers to professional identity formation in medical school viewed through the RToP lens

| Intrinsic enablers | Extrinsic enablers | Barriers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical student is able to: | Learning environment enables: | Student perceives or experiences: | |

| Societal Ring |

• Acknowledge societal expectations pertaining to professional role, responsibilities and codes of conduct 10,67,72,73,101,105,118,119 • Identify with medical professionals and wider healthcare community 2,5,6,54,63–65,78,81,120,121 • Exhibit professional behaviour in daily practice 74 • Fulfil entrusted responsibilities as a member of the healthcare team 2,65,70,73,77,103,122 • Build confidence with application of communication, counselling and clinical reasoning skills to contribute to the care of their patients 73,103,122 |

• Symbolic socialization events such as White Coat Ceremony or Honor Code 62,67,69,118,123 • Direct and repeat opportunities to interact with patients 62,67,69,118,123 • Meaningful professional relationships with multidisciplinary healthcare teams 5,8–10,54,64,65,71,72,74,82,84,89,93,96,97,99,102–104,107,124 • Clarity of role within team and wider healthcare system 9 • Formal curriculum to foster holistic, longitudinal knowledge acquisition and clinical education 2,5–7,10,54,62–65,67,69,71–74,76–79,81–84,88,89,91,93–97,100–105,109,110,118–132 • Art and humanities opportunities to foster creativity, acknowledge emotions and explore identities 89,92,119 • Hidden curriculum to align intended and enacted professional values and behaviours 2,4–10,54,62,64,65,68–72,75,78–80,82–84,88–90,93–95,97,99,103–105,119,121,122,132,133 |

• Disconnect between theoretical knowledge and application in clinical practice 97,98 • Heavy academic demands and competing responsibilities 82,106,107,130 • Tensions between personal values and broader professional identity instigated by challenging encounters 4,7,65,81 • Negative portrayal of profession by mainstream media or glamorization of traits such as cynicism 68,99,124 • Lack of opportunities or expectations to assume patient care responsibilities 88,98,101,103 • Difficulty navigating or fitting into new clinical environments 7 |

| Relational Ring | • Develop professional relationships with patients, peers and team members 72,84,88,97,124,132 |

• Supportive clinical interactions between patients and students; students and doctors 73,82,101,103,104,131,132 • Collaborative relationships among peers 74,81,84,101,128,129,131 • Open and supportive discussions with faculty and peers 65,73,74,81,129,131 • Access to appropriate mentorship, advising and role modeling 72,128 |

• Mismatch between personality and values with those of team members or patients 72,82,91,100 • Challenging relationships with team member, patients or peers 88 • Hierarchical structures in clinical environment deterring students from seeking help or speaking up 7,9,72,101 |

| Individual Ring |

• Show desire and sustain motivation to gain competence and engage in life-long learning 88,101 • Attend to emotions and engage in critical thinking and reflection 2,4–6,9,10,54,62,64,66–68,71–74,78–81,84,86,91,92,94,99,102,105,107,109,110,121,123,125–128,134 |

• Access to support systems including mentors and role models 5,69,71,80,93,121 • Exposure to challenging clinical experiences such as death and suffering 118 • Outlets for emotional and/or creative expression 89,92,119 |

• Tension between existing personal identity and aspiring professional identity 7,65,81 • Uncertainty or lack of confidence in clinical interactions that cast doubt on ability to fulfil professional tasks 54,64,80,96,99 |

Intrinsic factors refer to the medical student’s attitudes, values, beliefs, moral and philosophical leanings and decision-making processes. Extrinsic factors relate to the clinical environment. Many factors influence how medical students reconcile their experiences 7,9,67,72,103 and reflections within the Individual Ring of ideals, values, beliefs, and personal and professional self-concepts 4,91, while interactions 73,81,100,103–106 impact Relational and Societal Rings. These rings are further affected by how experiences and reflections take shape in medical school. In the absence of effective, appropriate or adequate support 7,72,98, enabling factors such as reflection 2,71,72,76,89,91,107 or socialization 69,72,98,101 may become barriers that impede the merging of students’ personal and professional identities.

-

4.

Medical School strategies to support PIF

Approaches that medical schools are taking to support PIF are presented in Table 2. The all-encompassing nature of these efforts signals an absence of clear or consistent approach across schools. What these reported strategies share is a foundation of pedagogical practices that view learning as a social construct, value role models, provide guided reflective practice, and institute longitudinal, inclusive and tailored forms of mentorship 71,76,80 within supportive learning environments 7,9,67,72,103 in which espoused and enacted values align. The formal 5,98,99 and hidden curricula 4,72,98 heavily influence students’ socialization into the medical community 7,72,98. As poignantly stated by Hodges et al.108, even if “a student can be prepared for excellent communication, collaboration, empathy, and patient-centered attitudes through years of formal training, just a few minutes in a work environment that does not model these behaviors will rapidly lead to their extinction in the student’s behaviors”. 108

Table 2.

Strategies adopted by Medical Schools to support Professional Identity Formation

| Strategies adopted by medical schools to support PIF | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Formal ethics and professionalism instruction |

Prioritizing principles of professionalism and professional identity formation consistently through curricular goals (professional roles, codes of practice, patient-centred care, ethics instruction, cultural sensitivity, clinical reasoning, communication skills, interprofessional education) using relevant instructional methods (e.g. didactic classroom learning, online modules, seminars, lectures, tutorials, group projects, small-group discussions, reflective writing, experiential learning, community care), and including a system for timely and appropriate feedback to help students improve in clinical capabilities Performing formative and summative assessment of professionalism as opportunities for learning, remediation, and in extreme cases, exclusion if a student severely violates codes of conduct |

2,6,7,10,54,62,64,67,71,73,74,77,78,80,82,84,88,89,91,93–97,100,101,103–105,109,110,119–132,135 |

| Informal and hidden curriculum | Acknowledging the significant influence of informal interactions with the medical community, role models and patients during profound life moments such as birth, death or suffering on student learning, values, attitudes, behaviours, specialty choice or perceived suitability for medicine | 5,8–10,54,62,69,75,82–84,88–90,93,95,97,103–105,119,121,122,132,133 |

| Learning environment | Establishing guidelines to ensure safe and open learning environments in which learner confidentiality is maintained, student behaviours such as competing, comparing, interrupting, prescribing and speaking on behalf of another are mitigated; open and non-judgmental discourse supported; and professional behaviour reinforced as an indicator of future conduct | 81,84,91,107,123,132 |

| Symbolic socialization | Conducting contextually appropriate symbolic events such as White Coat Ceremony to foster socialization into the profession | 62,67,69,118,123 |

| Medical humanities | Formally incorporating humanities with modules as outlets for creative release and emotional expression through art and stories that support empathy, compassion, tolerance of uncertainty and critical thinking on issues such as ethics and social justice | 89,92,119 |

| Reflective practice | Enabling deliberate and guided reflection strategies using discourse and small-group discussions with feedback throughout students’ medical education to help them uncover assumptions, explore different perspectives, make sense of challenging encounters, grapple with ethical quandaries, manage difficult emotions or conflict, and construct and deconstruct values and identity through comparisons between lived experiences and prevailing narratives of meaning, all aiming to inform future actions and decisions | 2,5,6,9,10,54,62,64,66–68,71,73,74,78–81,84,86,91,92,94,99,102,105,107,109,110,121,123,125–128,134 |

| Stories and storytelling | Offering opportunities for students to recollect and verbalize stories of patient encounters, make meaning as events are recalled and structured (i.e. “storied”), shape a personal framework of caring, and develop a coherent physician ideal through critical reflection | 90,103,105,110,129 |

| Mentorship | Providing formal, purposeful, accessible, inclusive and longitudinal mentorship, as one-on-one or group mentoring models, with qualified faculty aware of power dynamics of interactions with students and equipped with appropriate mentoring skills including feedback to guide students reflect on experiences, navigate professional life, and assimilate knowledge into clinical practice | 3,54,66,80,81,88,93,99,102,104,124,129 |

| Role models | Cultivating positive role models (e.g. doctors, near-peers, residents, faculty, inter-professional team members) who support students’ psychological well-being, encourage reflection, support learning, and demonstrate decision-making and professional values and attitudes in clinical and non-clinical contexts | 5,8–10,54,64,71,72,74,80,82,84,89,93,96,97,99,102–104,107,118,124 |

| Non-medical influences | Acknowledging the role of family, prior experiences, medical dramas and societal perceptions on students’ personal values vs. professional expectations, and supporting students to mitigate dissonance and enhance alignment between professional development (e.g. professional attitudes, roles and behaviours) and internal bearings and identity (e.g. personal values), which if left unaddressed could lead to anxiety, frustration, and feelings of inadequacy | 72,84 |

DISCUSSION

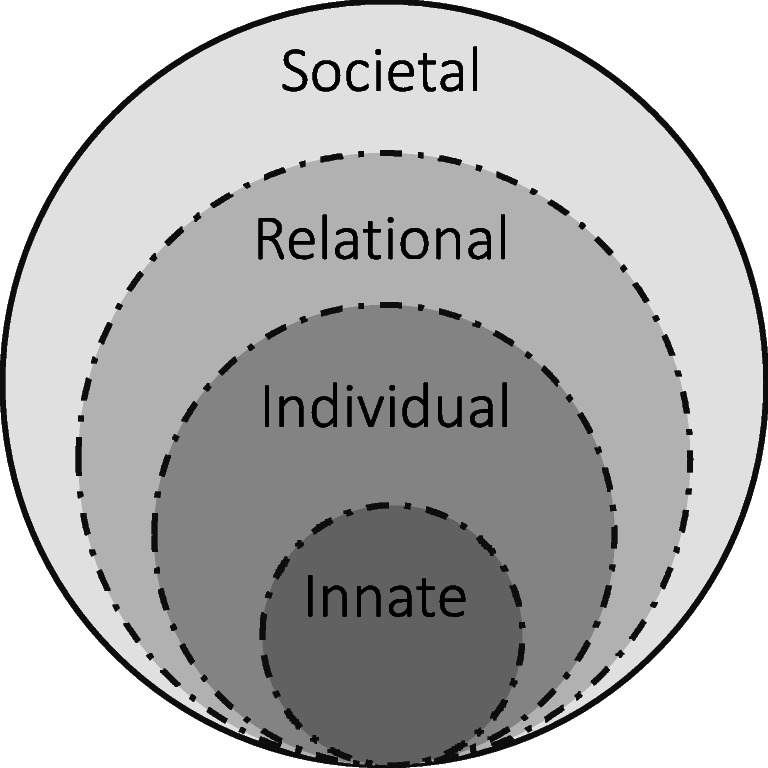

Findings from our review support the notion that PIF involves iterative construction, deconstruction and inculcation of professional beliefs, value systems and codes of conduct into a pre-existent concept of personhood. Students refine, reject or internalize new values, practices and behaviours while re-examining pre-existing ones. Such cycles of shaping and reshaping personal and professional identities are influenced by many factors including role models, reflections or responsibilities along the medical education continuum, as conceptualized in Figure 3. By viewing PIF through the RToP lens in this systematic scoping review, we identified a multitude of intrinsic and extrinsic factors that promote or impede individual, relational and societal aspects of a medical student’s personhood (Table 1). Importantly, if inadequately or inappropriately supported, enabling factors can become barriers to PIF.

Figure 3.

Integration of personal and professional identity entails a longitudinal, developmental process influenced by enabling (+) and disabling (−) factors that impact one’s personhood along the continuum of medical education

As different aspects of a medical student’s personhood evolve in medical school, personal and professional beliefs or values may pose as competing forces. Making sense of complex or ambiguous experiences necessitates a critical ability to question assumptions, attend to emotions and explore different perspectives. Deconstructing the self to pursue congruence among multiple existing identities can be disorienting or disconcerting. Left to their own devices, learners may consider open questioning of assumptions socioculturally inappropriate, or find existing power relations unapproachable. They may arrive at incomplete or incorrect conclusions, experience feelings of inadequacy and impostorship, and withdraw from learning activities to avoid being “found out”. The complex process of PIF, as an outcome of medical education, is thus not a solitary or self-directed exercise for students to steer in a vacuum. While successful formation of a professional identity has been linked to career success, a mismatch between a person’s internal bearings and professional roles and expectations can create anxiety, frustration, and feelings of inadequacy, sometimes leading the individual to leave the profession 109,110.

To support PIF, medical schools are offering attention and action in multiple domains as encapsulated in Table 2. Any measure implemented by a medical school will by its nature affect students at societal and relational levels, with downstream effects that reshape individual and even intrinsic aspects of their personhood. Caring for the dying, for example, can influence medical students’ conceptions of life, death and religion. However, our review does not shed light on how everyday personal interactions 111, gender roles, online experiences 72,84, religious beliefs or existential philosophies shape students’ understanding of the profession and professional roles. Donning on a white coat does not sever a student’s personal proclivities, motivations and priorities. To do so would ignore the humanism and multifarious sources of influence upon a student’s life. There is a dearth of data on the influence of a student’s personal roles — as a child, spouse, parent, friend, member of the larger community — on their professional conduct and identity. Further literature on this angle could illuminate the extent to which experiences in one’s personal sphere may influence professional values, attitudes and behaviours.

Professionalism and PIF are bidirectionally related but distinct entities. At a time when unethical behaviour, burnout and suicide in clinical practice are on the rise 31,112–115, it is all the more essential for medical schools to explicitly promote their expectations and ideals of the profession through formal instruction, reflective opportunities, mentoring and feedback, aided by processes such as individualized developmental portfolios 116,117, along with a multi-faceted program of assessment. The challenge with the latter remains a lack of consistency and clarity on the constituent constructs within professionalism and PIF through established theoretical frameworks.

LIMITATIONS

We acknowledge several limitations to this study. Guiding the analysis through the RToP lens is novel, and organization of factors within the four rings reflected the researchers’ own preconceptions. To reach consensus with minimal overlaps between and across categories required iterative communication to align our understanding of PIF influences and their relation to the rings. Further, despite a comprehensive search from snowballing of references and oversight from content experts, it is possible to have missed relevant literature. The included articles, by nature of scoping reviews, were of varying categories and caliber, and the majority represented Western perspectives, questioning generalizability within different contexts.

CONCLUSION

PIF is a complex, non-linear and fluid process through which medical students navigate competing influences between their professional roles and personal lives, and iteratively construct and deconstruct evolving views of the self. In the absence of a unifying theoretical framework, we explored this process through the lens of personhood and encapsulated key factors that promote or hinder students’ identity development on individual, relational or societal levels. Also captured were the all-encompassing strategies that medical schools implement to support their students’ socialization into the profession. Deliberate efforts to foster inspiring mentored relationships and individualized guided reflections in supportive learning environments can foster the agency for students to harmonize their personal and professional identities over time, with the ultimate aim of improving practice on individual, institutional and societal levels.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 28 kb)

(DOCX 16 kb)

(DOCX 19 kb)

(DOCX 36 kb)

(PDF 13842 kb)

(PDF 427 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to dedicate this paper to the late Dr. S Radha Krishna whose advice and ideas were integral to the success of this study. The authors would also like to thank the reviewers whose comments greatly enhanced this paper.

Abbreviations

- PIF

professional identity formation

- RToP

ring theory of personhood

- SEBA

systematic evidence-based approach

- SSR

systematic scoping review

- YLLSoM

Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine

- NUS

National University of Singapore

- NCCS

National Cancer Centre Singapore

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PICOS

population, intervention, comparison, outcome, study design

- MERSQI

Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument

- COREQ

Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies

- BEME

Best Evidence Medical Education

- STORIES

Structured approach to the Reporting In healthcare education of Evidence Synthesis

Author Contribution

SS, YNT, AEHH, YHT, YTO, CWSC, ASIL, AMCC, MC and LKRK conceived of the study and led the design, data collection, analysis and drafting of the manuscript.

SG, CSK, WYL, RSMW, HZBG, SL, JRMT, RBQL, NPXC, NHAK and LHET participated in study design and conducted data collection.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this review are included in this published article (and its appendices).

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

NA

Consent for Publication

NA

Conflict of Interest

SS, YNT, AEHH, YHT, SG, CSK, WYL, RSMW, HZBG, SL, JRMT, RBQL, YTO, NPXC, CWSC, NHAK, ASIL, LHET, AMCC, MC, LKRK have no competing interests and no funding was received for this review.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Shiva Sarraf-Yazdi, Email: shiva.sarraf@duke-nus.edu.sg.

Yao Neng Teo, Email: teoyaoneng@gmail.com.

Ashley Ern Hui How, Email: ashleyhowernhui@gmail.com.

Yao Hao Teo, Email: teoyaohao@gmail.com.

Sherill Goh, Email: sherillgoh@hotmail.com.

Cheryl Shumin Kow, Email: cheryl148@gmail.com.

Wei Yi Lam, Email: iamweiyi98@gmail.com.

Ruth Si Man Wong, Email: ruthwsm@gmail.com.

Haziratul Zakirah Binte Ghazali, Email: hzakirah@gmail.com.

Sarah-Kei Lauw, Email: sarahkeilauw@gmail.com.

Javier Rui Ming Tan, Email: javiertanrm@gmail.com.

Ryan Bing Qian Lee, Email: lbq.bingy@gmail.com.

Yun Ting Ong, Email: yunting.ong08@gmail.com.

Natalie Pei Xin Chan, Email: nataliechan297@gmail.com.

Clarissa Wei Shuen Cheong, Email: clarissacheongws@gmail.com.

Nur Haidah Ahmad Kamal, Email: haidah.ak@gmail.com.

Alexia Sze Inn Lee, Email: lee.sze.inn@nccs.com.sg.

Lorraine Hui En Tan, Email: lorraine.the@gmail.com.

Annelissa Mien Chew Chin, Email: annelissa_chin@nus.edu.sg.

Min Chiam, Email: chiam.min@nccs.com.sg.

Lalit Kumar Radha Krishna, Email: lalit.radha-krishna@liverpool.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Matsui T, Sato M, Kato Y, Nishigori H. Professional identity formation of female doctors in Japan–gap between the married and unmarried. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1479-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holden M, Buck E, Clark M, Szauter K, Trumble J. Professional Identity Formation in Medical Education: The Convergence of Multiple Domains. HEC Forum. 2012;24(4):245–255. doi: 10.1007/s10730-012-9197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frost HD, Regehr G. “I AM a doctor”: Negotiating the discourses of standardization and diversity in professional identity construction. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1570–1577. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a34b05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monrouxe LV, Sweeney K. First do no self-harm: Understanding and promoting physician stress resilience. New York: Oxford University Press; 2013. Between two worlds: Medical students narrating identity tensions; pp. 44–66. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldie J. The formation of professional identity in medical students: Considerations for educators. Med Teach. 2012;34(9):e641–e648. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.687476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holden MD, Buck E, Luk J, et al. Professional Identity Formation: Creating a Longitudinal Framework Through TIME (Transformation in Medical Education) Acad Med. 2015;90(6):761–767. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soo J, Brett-MacLean P, Cave M-T, Oswald A. At the precipice: A prospective exploration of medical students’ expectations of the pre-clerkship to clerkship transition. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2016;21(1):141–162. doi: 10.1007/s10459-015-9620-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schrewe B, Bates J, Pratt D, Ruitenberg CW, McKellin WH. The Big D(eal): Professional identity through discursive constructions of ‘patient’. Med Educ. 2017;51(6):656–668. doi: 10.1111/medu.13299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barr J, Bull R, Rooney K. Developing a patient focussed professional identity: An exploratory investigation of medical students’ encounters with patient partnership in learning. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2015;20(2):325–338. doi: 10.1007/s10459-014-9530-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wald HS, White J, Reis SP, Esquibel AY, Anthony D. Grappling with complexity: Medical students’ reflective writings about challenging patient encounters as a window into professional identity formation. Med Teach. 2019;41(2):152–160. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1475727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moss JM, Gibson DM, Dollarhide CT. Professional identity development: A grounded theory of transformational tasks of counselors. J Couns Psychol. 2014;92(1):3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buron B. Levels of personhood: A model for dementia care. Geriatr Nurs. 2008;29(5):324–332. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dennett DC. Brainstorms: Philosophical Essays on Mind and Psychology. 1978. In: MIT Press, Cambridge, MA; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Locke J. An essay concerning principles of human understanding (1836) Inc.: Hackett Publishing Company; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kant I. Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785) In: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cranford RE, Smith DR. Consciousness: the most critical moral (constitutional) standard for human personhood. AJLM. 1987;13:233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jowett B. The Republic of Plato. London. New York: Macmillan; 1888. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singer P. Rethinking Life and Death. Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fletcher JF. Humanhood: Essays in biomedical ethics. Buffalo, New York: Prometheus Books; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor C. Sources of the self: The making of the modern identity. Harvard University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgs J, Jones MA, Loftus S, Christensen N. Clinical Reasoning in the Health Professions. 3rd Edition. J Chiropr Educ. 2008;22(2):161–162. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avorn J. The Psychology of Clinical Decision Making - Implications for Medication Use. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(8):689–691. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1714987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramondetta L, Brown A, Richardson G, et al. Religious and spiritual beliefs of gynecologic oncologists may influence medical decision making. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21(3):573–581. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31820ba507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krishna LKR, Alsuwaigh R. Understanding the Fluid Nature of Personhood–the Ring Theory of Personhood. Bioethics. 2015;29(3):171–181. doi: 10.1111/bioe.12085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alsuwaigh R, Krishna LKR. The compensatory nature of personhood. Asian Bioeth Rev. 2014;6(4):332–342. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krishna LKR, Kwek SY. The changing face of personhood at the end of life: The ring theory of personhood. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(4):1123. doi: 10.1017/S1478951514000686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krishna LKR, Alsuwaigh R, Miti PT, Wei SS, Ling KH, Manoharan D. The influence of the family in conceptions of personhood in the palliative care setting in Singapore and its influence upon decision making. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2014;31(6):645–654. doi: 10.1177/1049909113500136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach BMC Med Res Method. 2018;18(143). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Kow CS, Teo YH, Teo YN, et al. A systematic scoping review of ethical issues in mentoring in medical schools. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02169-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krishna LKR, Tan LHE, Ong YT, et al. Enhancing Mentoring in Palliative Care: An Evidence Based Mentoring Framework. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120520957649. doi: 10.1177/2382120520957649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ngiam LXL, Ong YT, Ng JX, et al. Impact of Caring for Terminally Ill Children on Physicians: A Systematic Scoping Review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2021;38(4):396-418. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;350:g7647. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Soares C, Khalil H, Parker D. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2015: Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews. In: Adelaide, SA Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2015: http://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/sumari/Reviewers-Manual_Methodology-for-JBI-Scoping-Reviews_2015_v1.pdf. Accessed 29 Apr 2019.

- 37.Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–146. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reed DA, Beckman TJ, Wright SM, Levine RB, Kern DE, Cook DA. Predictive validity evidence for medical education research study quality instrument scores: quality of submissions to JGIM’s Medical Education Special Issue. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):903–907. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0664-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mertz M. How to tackle the conundrum of quality appraisal in systematic reviews of normative literature/information? Analysing the problems of three possible strategies (translation of a German paper). BMC Med Ethics. 2019;20(1):81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Majid U, Vanstone M. Appraising Qualitative Research for Evidence Syntheses: A Compendium of Quality Appraisal Tools. Qual Healt Res. 2018;28(13):2115–2131. doi: 10.1177/1049732318785358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ng YX, Koh ZYK, Yap HW, et al. Assessing mentoring: A scoping review of mentoring assessment tools in internal medicine between 1990 and 2019. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0232511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chua WJ, Cheong CWS, Lee FQH, et al. Structuring Mentoring in Medicine and Surgery. A Systematic Scoping Review of Mentoring Programs Between 2000 and 2019. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2020;40(3):158–168. doi: 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soemantri D, Herrera C, Riquelme A. Measuring the educational environment in health professions studies: a systematic review. Med Teach. 2010;32(12):947–952. doi: 10.3109/01421591003686229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Riquelme A, Herrera C, Aranis C, Oporto J, Padilla O. Psychometric analyses and internal consistency of the PHEEM questionnaire to measure the clinical learning environment in the clerkship of a Medical School in Chile. Med Teach. 2009;31(6):e221–e225. doi: 10.1080/01421590902866226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haig A, Dozier M. BEME Guide no 3: systematic searching for evidence in medical education--Part 1: Sources of information. Med Teach. 2003;25(4):352–363. doi: 10.1080/0142159031000136815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gordon M, Gibbs T. STORIES statement: publication standards for healthcare education evidence synthesis. BMC medicine. 2014;12(1):143. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0143-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. US: Sage Publications; 1998.

- 52.Sawatsky AP, Parekh N, Muula AS, Mbata I, Bui T. Cultural implications of mentoring in sub-Saharan Africa: a qualitative study. Med Educ. 2016;50(6):657–669. doi: 10.1111/medu.12999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The Qualitative Content Analysis Process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau J, Snell L, Steinert Y. A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialization of medical students and residents: A guide for medical educators. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):718–725. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moss PA, Haertel EH. Engaging methodological pluralism. In: Gitomer D, Bell C, editors. Handbook of Research on Teaching. Washington, DC: AERA; 2016. pp. 127–247. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Buckingham J, Pawson R. RAMESES publication standards: meta-narrative reviews. BMC Med. 2013;11(1):20. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews: A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme Version 1. Lancaster University; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 58.France EF, Uny I, Ring N, et al. A methodological systematic review of meta-ethnography conduct to articulate the complex analytical phases. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s12874-019-0670-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. California: Sage Publications; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 60.France EF, Wells M, Lang H, Williams B. Why, when and how to update a meta-ethnography qualitative synthesis. Syst Rev. 2016;5:44. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0218-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Frei E, Stamm M, Buddeberg-Fischer B. Mentoring programs for medical students - A review of the PubMed literature 2000-2008. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:32. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Amending Miller’s pyramid to include professional identity formation. Acad Med. 2016;91(2):180–185. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hafferty FW, Michalec B, Martimianakis MA, Tilburt JC. Alternative Framings, Countervailing Visions: Locating the “P” in Professional Identity Formation. Acad Med. 2016;91(2):171–174. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Olive KE, Abercrombie CL. Developing a PSShysician′s Professional Identity Through Medical Education. Am J Med Sci. 2017;353(2):101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rabow MW, Wrubel J, Remen RN. Authentic community as an educational strategy for advancing professionalism: A national evaluation of the Healer’s Art course. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(10):1422–1428. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0274-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kalen S, Ponzer S, Seeberger A, Kiessling A, Silen C. Longitudinal mentorship to support the development of medical students’ future professional role: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:97. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0383-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Byszewski A, Gill JS, Lochnan H. Socialization to professionalism in medical schools: a Canadian experience. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:204. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0486-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Iserson KV. Talking About Professionalism Through the Lens of Professional Identity. AEM Educ Train. 2019;3(1):105–112. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. Reframing Medical Education to Support Professional Identity Formation. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1446–1451. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boudreau JD, Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Physicianship: Educating for professionalism in the post-Flexnarian era. Perspect Biol Med. 2011;54(1):89–105. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2011.0000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Teaching professionalism - Why, What and How. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2012;4(4):259–265. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wilson I, Cowin LS, Johnson M, Young H. Professional identity in medical students: Pedagogical challenges to medical education. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25(4):369–373. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2013.827968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hatem DS, Halpin T. Becoming Doctors: Examining Student Narratives to Understand the Process of Professional Identity Formation Within a Learning Community. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2019;6:2382120519834546. doi: 10.1177/2382120519834546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Findyartini A, Sudarsono NC. Remediating lapses in professionalism among undergraduate pre-clinical medical students in an Asian Institution: a multimodal approach. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1206-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Boudreau JD, Fuks A. The Humanities in Medical Education: Ways of Knowing, Doing and Being. J Med Humanit. 2015;36(4):321-336. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Bynum WEI, Artino ARJ. Who Am I, and Who Do I Strive to Be? Applying a Theory of Self-Conscious Emotions to Medical Education. Acad Med. 2018;93(6):874–880. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bogetz AL, Bogetz JF. An Evolving Identity: How Chronic Care Is Transforming What it Means to Be a Physician. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(6):664–668. doi: 10.1007/s40596-014-0141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sklar DP. How do I figure out what I want to do if I don’t know who I am supposed to be? Acad Med. 2015;90(6):695–696. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Slotnick HB. How doctors learn: Education and learning across the medical-school-to-practice trajectory. Acad Med. 2001;76:1013–1026. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200110000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rabow M, Remen R, Parmelee D, Inui T. Professional Formation: Extending Medicine’s Lineage of Service Into the Next Century. Acad Med. 2010;85:310–317. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c887f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Boudreau JD, Macdonald ME, Steinert Y. Affirming professional identities through an apprenticeship: insights from a four-year longitudinal case study. Acad Med. 2014;89(7):1038–1045. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Azmand S, Ebrahimi S, Iman M, Asemani O. Learning professionalism through hidden curriculum: Iranian medical students’ perspective. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2018;11:10. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.ten Cate O, Gruppen LD, Kogan JR, Lingard LA, Teunissen PW. Time-Variable Training in Medicine: Theoretical Considerations. Acad Med. 2018;93(3S):S6–S11. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wong A, Trollope-Kumar K. Reflections: An inquiry into medical students’ professional identity formation. Med Educ. 2014;48(5):489–501. doi: 10.1111/medu.12382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Barone MA, Vercio C, Jirasevijinda T. Supporting the Development of Professional Identity in the Millennial Learner. Pediatrics. 2019;143(3):e20183988. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 86.Stephens MB, Bader KS, Myers KR, Walker MS, Varpio L. Examining Professional Identity Formation Through the Ancient Art of Mask-Making. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(7):1113–1115. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04954-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Miller E, Balmer D, Hermann N, Graham G, Charon R. Sounding narrative medicine: studying students’ professional identity development at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. Acad Med. 2014;89(2):335–342. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gaufberg E, Bor D, Dinardo P, et al. In Pursuit of Educational Integrity: Professional Identity Formation in the Harvard Medical School Cambridge Integrated Clerkship. Perspect Biol Med. 2017;60(2):258–274. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2017.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Volpe RL, Hopkins M, Van Scoy LJ, Wolpaw DR, Thompson BM. Does Pre-clerkship Medical Humanities Curriculum Support Professional Identity Formation? Early Insights from a Qualitative Study. Med Sci Educ. 2019;29(2):515–521. doi: 10.1007/s40670-018-00682-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Figley C, Huggard P. Rees C. First Do No Self Harm: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Peterson WJ, House JB. Sozener CB, Santen SA. Understanding the Struggles to Be a Medical Provider: View Through Medical Student Essays. J Emerg Med. 2018;54(1):102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shapiro J, Youm J, Heare M, et al. Medical Students’ Efforts to Integrate and/or Reclaim Authentic Identity: Insights from a Mask-Making Exercise. J Med Humanit. 2018;39(4):483–501. doi: 10.1007/s10912-018-9534-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fergus KB, Teale B, Sivapragasam M, Mesina O, Stergiopoulos E. Medical students are not blank slates: Positionality and curriculum interact to develop professional identity. Perspect Med Educ. 2018;7(1):5–7. doi: 10.1007/s40037-017-0402-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Aagaard EM, Moscoso L. Practical implications of compassionate off-ramps for medical students. Acad Med. 2019;94(5):619–622. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sharpless J, Baldwin N, Cook R, et al. The becoming: students’ reflections on the process of professional identity formation in medical education. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):713–717. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cruess SR, Cruess RL, Steinert Y. Supporting the development of a professional identity: General principles. Med Teach. 2019;41(6):641–649. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1536260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kavas MV, Demiroren M, Kosan AM, Karahan ST, Yalim NY. Turkish students’ perceptions of professionalism at the beginning and at the end of medical education: a cross-sectional qualitative study. Med Educ Online. 2015;20:26614. doi: 10.3402/meo.v20.26614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Schei E, Johnsrud RE, Mildestvedt T, Pedersen R, Hjorleifsson S. Trustingly bewildered. How first-year medical students make sense of their learning experience in a traditional, preclinical curriculum. Med Educ Online. 2018;23(1):1500344. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2018.1500344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chuang AW, Nuthalapaty FS, Casey PM, et al. To the point: reviews in medical education—taking control of the hidden curriculum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(4):316.e311–316.e316. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Steinauer JE, O’Sullivan P, Preskill F, Ten Cate O, Teherani A. What Makes “Difficult Patients” Difficult for Medical Students? Acad Med. 2018;93(9):1359–1366. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Smith SE, Tallentire VR, Cameron HS, Wood SM. The effects of contributing to patient care on medical students’ workplace learning. Med Educ. 2013;47(12):1184–1196. doi: 10.1111/medu.12217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Byars LA, Stephens MB, Durning SJ, Denton GD. A Curricular Addition Using Art to Enhance Reflection on Professional Values. Mil Med. 2015;180(suppl_4):88–91. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Konkin J, Suddards C. Creating stories to live by: caring and professional identity formation in a longitudinal integrated clerkship. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2012;17(4):585–596. doi: 10.1007/s10459-011-9335-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.De Grasset J, Audetat MC, Bajwa N, et al. Medical students’ professional identity development from being actors in an objective structured teaching exercise. Med Teach. 2018;40(11):1151–1158. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1457212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jarvis-Selinger S, MacNeil KA, Costello GRL, Lee K, Holmes CL. Understanding Professional Identity Formation in Early Clerkship: A Novel Framework. Acad Med. 2019;94(10):1574–1580. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ahmad A, Bahri Yusoff MS, Zahiruddin Wan Mohammad WM, Mat Nor MZ. Nurturing professional identity through a community based education program: medical students experience. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2018;13(2):113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wang XM, Swinton M, You JJ. Medical students’ experiences with goals of care discussions and their impact on professional identity formation. Med Educ. 2019;53(12):1230–1242. doi: 10.1111/medu.14006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hodges BD, Kuper A. Theory and practice in the design and conduct of graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2012;87(1):25–33. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318238e069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Reis SP, Wald HS. Contemplating medicine during the Third Reich: Scaffolding professional identity formation for medical students. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):770–773. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Easton G. How medical teachers use narratives in lectures: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:3. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0498-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Finn G, Garner J, Sawdon M. ‘You’re judged all the time!’Students’ views on professionalism: a multicentre study. Med Educ. 2010;44(8):814–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Dzau VJ, Kirch DG, Nasca TJ. To Care Is Human — Collectively Confronting the Clinician-Burnout Crisis. NEJM. 2018;378:312–314. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1715127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wright AA, M.P.H., Katz IT. Beyond Burnout — Redesigning Care to Restore Meaning and Sanity for Physicians. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:309–311. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1716845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lee FQH, Chua WJ, Cheong CWS, et al. A Systematic Scoping Review of Ethical Issues in Mentoring in Surgery. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2019;6:2382120519888915. doi: 10.1177/2382120519888915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Cheong CWS, Chia EWY, Tay KT, et al. A systematic scoping review of ethical issues in mentoring in internal medicine, family medicine and academic medicine. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2020;25(2):415–439. doi: 10.1007/s10459-019-09934-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Van Tartwijk J, Driessen EW. Portfolios for assessment and learning: AMEE Guide no. 45. Medical Teacher. 2009;31(9):790–801. doi: 10.1080/01421590903139201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Colbert CY, Ownby AR, Butler PM. A Review of Portfolio Use in Residency Programs and Considerations before Implementation. Teaching and Learning in Medicine. 2008;20(4):340–345. doi: 10.1080/10401330802384912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kay D, Berry A, Coles NA. What experiences in medical school trigger professional identity development? Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(1):17–25. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2018.1444487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Beck J, Chretien K, Kind T. Professional Identity Development Through Service Learning: A Qualitative Study of First-Year Medical Students Volunteering at a Medical Specialty Camp. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2015;54(13):1276–1282. doi: 10.1177/0009922815571108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Helmich E, Dornan T. Do you really want to be a doctor? The highs and lows of identity development. Med Educ. 2012;46(2):132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hargreaves K. Reflection in medical education. JUTLP. 2016;13(2):6. [Google Scholar]

- 122.van der Zwet J, Zwietering PJ, Teunissen PW, van der Vleuten CP, Scherpbier AJ. Workplace learning from a socio-cultural perspective: creating developmental space during the general practice clerkship. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2011;16(3):359–373. doi: 10.1007/s10459-010-9268-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Shiozawa T, Glauben M, Banzhaf M, et al. An Insight into Professional Identity Formation: Qualitative Analyses of Two Reflection Interventions During the Dissection Course. Anat Sci Educ. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 124.Schweller M, Ribeiro DL, Celeri EV, de Carvalho-Filho MA. Nurturing virtues of the medical profession: does it enhance medical students’ empathy? Int J Med Educ. 2017;8:262–267. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5951.6044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ten Cate O. What is a 21st-century doctor? Rethinking the significance of the medical degree. Acad Med. 2014;89(7):966–969. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Till A, McKimm J, Swanwick T. Twelve tips for integrating leadership development into undergraduate medical education. Med Teach. 2018;40(12):1214–1220. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1392009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Lin L. Fostering students’ professional identity using critical incident technique. Med Educ. 2012;46(11):1132–1133. doi: 10.1111/medu.12040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Seymour P, Watt M, MacKenzie M, Gallea M. Professional Competencies ToolKit: Using Flash Cards to Teach Reflective Practice to Medical Students in Clinical Clerkship. MedEdPORTAL. 2018;14:10750. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Cave MT, Clandinin DJ. Revisiting the journal club. Med Teach. 2007;29(4):365–370. doi: 10.1080/01421590701477415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Madill A, Latchford G. Identity change and the human dissection experience over the first year of medical training. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(7):1637–1647. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Swick HM, Simpson DE, Van Susteren TJ. Fostering the professional development of medical students. Teach Learn Med. 1995;7(1):55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Schei E, Knoop HS, Gismervik MN, Mylopoulos M, Boudreau JD. Stretching the Comfort Zone: Using Early Clinical Contact to Influence Professional Identity Formation in Medical Students. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2019;6:2382120519843875. doi: 10.1177/2382120519843875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Noguera A, Robledano R, Garralda E. Palliative care teaching shapes medical undergraduate students’ professional development: a scoping review. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2018;12(4):495–503. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Roper L, Foster K, Garlan K, Jorm C. The challenge of authenticity for medical students. Clin Teach. 2016;13(2):130–133. doi: 10.1111/tct.12440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Bynum IV WE, Artino Jr ARJAM. Who am I, and who do I strive to be? Applying a theory of self-conscious emotions to medical education. 2018;93(6):874-880. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 28 kb)

(DOCX 16 kb)

(DOCX 19 kb)

(DOCX 36 kb)

(PDF 13842 kb)

(PDF 427 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this review are included in this published article (and its appendices).