Abstract

Background

The opioid epidemic is widely recognized as a legislative priority, but there is substantial variation in state adoption of evidence-based policy. State legislators’ use of social media to disseminate information and to indicate support for specific initiatives continues to grow and may reflect legislators’ openness to opioid-related policy change.

Objective

We sought to identify changes in the national dialogue regarding the opioid epidemic among Democratic and Republican state legislators and to estimate changing partisanship around understanding and addressing the epidemic over time.

Design

Longitudinal natural language processing analysis.

Participants

A total of 4083 US state legislators in office between 2014 and 2019 with any opioid-related social media posts.

Main Measures

Association between opioid-related post volume and state overdose mortality, as measured by Kendall’s rank correlation coefficient. Latent Dirichlet allocation analysis of all social media posts to identify key opioid-related topics. Longitudinal analysis of differences in the prevalence of key topics among Democrats and Republicans over time.

Key Results

In total, 43,558 social media posts met inclusion criteria, with the vast majority to Twitter (n=28,564; 65.6%) or Facebook (n=14,283; 32.8%). Posts were more likely to mention fentanyl and less likely to mention heroin over time. The volume of opioid-related content was positively associated with state-level unintentional overdose mortality among both Democrats (tau=0.42, P<.001) and Republicans (tau=0.39, P<.001). Democrats’ social media content has increasingly spoken to holding pharmaceutical companies accountable, while Republicans’ social media content has increasingly spoken to curbing illicit drug trade. Overall, partisanship across topics increased from 2016 to 2019.

Conclusion

The volume of opioid-related social media posts by US state legislators between 2014 and 2019 is associated with state-level overdose mortality, but the content across parties is significantly different. Democrats’ and Republicans’ social media posts may reflect growing partisanship regarding how best to address the overdose epidemic.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-021-06678-9.

KEY WORDS: state legislators, opioid policy, social media, natural language processing

INTRODUCTION

The opioid epidemic in the United States (US) continues to evolve, with a 4% growth in opioid-related overdose deaths from December 2018 to November 2019, resulting in approximately 137 deaths per day.1 Rising overdose rates are fueled by an increasing proportion of deaths involving synthetic opioids or psychostimulants.2, 3 Trends differ considerably by state: Arkansas saw an 18.3% drop in estimated deaths, while South Dakota saw a 61.8% rise.1

Variations in state policy, and in implementation of evidence-based practices, contribute to mortality trends. Evidence-based interventions include laws regulating prescribing,4, 5 medication treatment for opioid use disorder,6, 7 and access to naloxone.8, 9 Political partisanship affects opioid-related policies, and rates of opioid use disorder may impact local politics. For instance, counties with greater rates of chronic opioid use were also more likely to vote Republican in the 2016 presidential election, with approximately two-thirds of the association explained by socioeconomic factors.10 Between 2014 and 2018, states with Republican control passed more legislation to address the opioid epidemic than states with Democrat control, but total spending on the opioid epidemic was smaller in Republican states after accounting for the impact of Medicaid expansion.11 Among state legislators, support for opioid use disorder parity laws—laws that require equal insurance benefits for behavioral health and physical health treatment—has been associated with Democratic affiliation. 12

The language used in public-facing content in traditional media and on social media both affects and reflects public sentiment. An analysis of traditional news language identified increasing mentions of medication for opioid use disorder nationally but more negative framing of medication treatment within states with high overdose mortality.13 Public language can contribute towards opioid use disorder stigma, which is associated with lower support for evidence-based interventions and higher levels of support for punitive interventions.14–16 Legislators’ social media posts may also reflect policy attention in real time and constituents’ priorities.17, 18 Cross-party interaction among legislators on social media occurs to a greater extent than co-sponsorship.19 Twitter and Facebook may therefore serve as repositories of political opinion and indicators of key shifts in political priorities and partisanship.

The objectives of this study were to examine state legislators’ opioid-related social media posts in order to understand the relationship between state overdose death rates and legislators’ social media activity; describe changing topics of discussion over time; and examine longitudinal transitions in opioid-related partisanship.

METHODS

Data Source

We identified state legislators’ social media posts about opioids from 2014 to 2019. We obtained social media data from Quorum (www.quorum.us), a software platform that collects documents with policy relevance at the state and national level, including the social media content of politicians during their time in office. We searched the social media content of all members of the upper and lower houses of the 50 US state legislatures for posts mentioning one of the following terms: “opioid(s),” “opiate(s),” “narcotic(s),” “heroin,” “fentanyl,” “oxycodone,” “oxycontin,” or “Percocet.” The term list reflects a combination of general terms for the opioid class and specific prescription opioids (oxycodone), synthetic opioids (fentanyl), and heroin.16, 20 We considered the inclusion of additional terms for medications in the opioid class, but inclusion of these terms did not substantially impact the final number of social media posts (Online Appendix Table 1). We did not explicitly search for posts containing words relative to overdose reversal (e.g., “naloxone”) or medication treatment for opioid use disorder (e.g., “buprenorphine”) so as not to artificially inflate the incidence of these topics relative to others. Further details regarding arrival at the final search criteria can be found in the Online Appendix. We included duplicated posts both within the same platform (e.g., retweets) and across platforms (e.g., Facebook and Twitter). In doing so, we assumed that a duplicate represented a re-endorsement of the original language and a wider audience for the content.

To control for the number of legislators, we obtained the yearly number of legislators by state and party from the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL).21 The total number of state legislators (N= 7383) and the number of legislators by state were constant across all years analyzed, while the number of legislators by party varied each year. These numbers were used in the calculations of social media posts per legislator and per legislator by party in the descriptive analysis, as described below, but did not affect the natural language processing analyses.

To assess correlations between the volume of state legislators’ social media activity and the state opioid overdose mortality rate, we obtained state-level unintentional overdose mortality rates from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (CDC WONDER) for all available years of overlap with the social media data (2014–2018).22

Descriptive Analysis

We used summary statistics to describe the volume of posts on each social media platform and across parties and legislative bodies. We calculated the total number of opioid-related social media posts per state legislator, and the number of posts per legislator mentioning each search term, per calendar quarter (3-month period). We estimated differences between Democratic and Republican use of each of the search terms using the Pearson chi-square test. We used NCSL data to calculate the number of posts per legislator in a given state both overall and by party (continuous, non-normally distributed data), and we compared these numbers to states’ mean unintentional overdose mortality (again continuous and non-normally distributed) using Kendall's rank correlation coefficient.

Natural Language Processing

To understand cross-party differences in language use, we looked at both words and topics. We compared the frequency of word use across social media posts in each party. To evaluate the thematic content of the opioid-related posts, we used latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA), a machine learning–based approach to defining naturally occurring topics.23, 24 LDA identifies a user-specified number of groupings of words across documents by iteratively fitting two probability distributions, a per-topic word distribution, and a per-document topic distribution, each summing to one. Documents are treated as a “bag of words” in that word order is ignored. As an example, a topic most strongly defined by the words “overdose,” “naloxone,” and “save” might represent a large proportion of the tweet, “Our state has started a naloxone distribution program to reduce overdoses, and it will save many lives.”

We excluded hashtags, links, and mentions of other users from our LDA analysis. Using a combination of model coherence scores and evaluations of topic interpretability, we elected to fit a 20-topic model. Authors DCS and AKA independently evaluated each topic for thematic meaning by reviewing the ten words and ten social media posts most associated with each topic. Topics for which authors DCS and AKA agreed on thematic meaning were included in subsequent analyses.25, 26 Further details regarding language pre-processing and model fitting are described (Online Appendix).

To analyze the distribution of LDA topics across political parties, we compared the mean per-document topic probability (a non-normal, continuous variable with minimum zero and maximum one) across all posts by Democrats and Republicans using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. We considered a difference significant according to a cut-off of a Bonferroni corrected P<0.001 (corrected value P<5 × 10-5), consistent with prior LDA analyses.27, 28 To describe the change in topic prevalence over time, we calculated the mean topic probability across posts, stratified by party, for each of the 24 three-month quarters.29–31 In order to understand whether attention to topics was converging or diverging over time, for each topic, we calculated the absolute difference in mean topic probability among all Democrats’ and Republicans’ posts by calendar quarter. We then summed these absolute differences across all topics. If all topics were equally represented in Democrats’ and Republicans’ posts, this would have led to a sum of absolute differences of zero. If, on the other hand, Democrats and Republicans were perfectly opposed, such that the mean topic probability was 1 for one party and 0 for the other for all topics, the sum of absolute differences would have a theoretical maximum value equal to the final number of topics. We calculated and plotted these values both for the subset of consensus topics and for the total collection of 20 topics. Furthermore, we repeated all longitudinal LDA analyses after excluding retweets and duplicate posts (Online Appendix).

All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.6.1.32 This study is exempt under University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board guidelines as it does not meet criteria for human subject research.

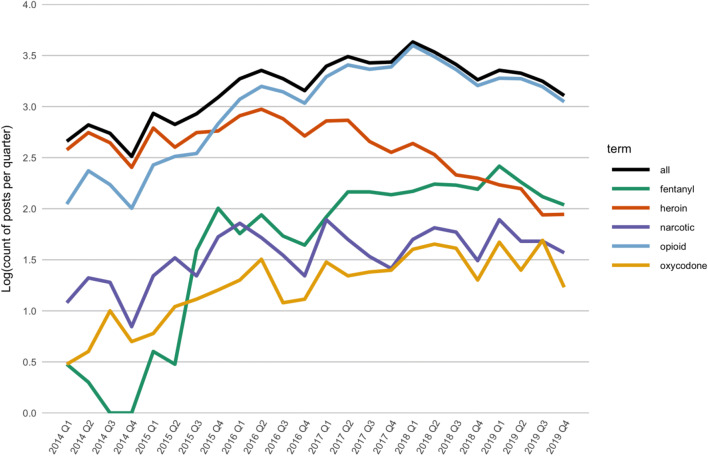

RESULTS

We identified 43,558 opioid-related social media posts meeting inclusion criteria from 4083 unique state legislators between 2014 and 2019. The numbers of posts by year, social media platform, legislator party, and legislative division are reported in Table 1. Most posts were to Twitter (28,564; 65.6%) and Facebook (14,283; 32.8%), with Republicans more likely to post to Facebook than Democrats. Among Twitter posts, 14,626 (51.2%) were retweets. Few posts were verbatim repeats across platforms (197; 0.5%). The number of opioid-related social media posts rose steadily between 2014 and 2018, but declined from 2018 to 2019. The number of posts mentioning “heroin” declined over the 6-year time period, while those mentioning “opioid(s)” or “fentanyl” rose (Fig. 1). Republicans were more likely to use the terms “heroin,” “fentanyl,” and “narcotic” (P<.001), while Democrats were more likely to use the terms “opioid,” and “oxycodone,” “oxycontin,” or “Percocet” (P<.001) (Online Appendix Table 3). The number of posts per state legislator was correlated with the state’s unintentional overdose mortality rate (tau=0.40, P<.001), with the strength of correlation similar among Democratic legislators (tau=0.42, P<.001) and Republican legislators (tau=0.39, P<.001).

Table 1.

Descriptive Information Regarding the Number and Percent of Posts by Category, Both Overall and with Posts Divided between Democrats and Republicans

| Total, n=43,427 (100%) | Democrat-generated, n=21,720(100%) | Republican-generated, n=21,126 (100%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Party of poster | |||

| Democrats | 21,720 (49.9) | - | - |

| Republicans | 21,126 (48.5) | - | - |

| Other (“independent”, “non-designated”, and “other”) | 712 (1.6) | - | - |

| Yeara | |||

| 2014 | 1990 (4.6) | 706 (3.3) | 1274 (6.0) |

| 2015 | 3606 (8.3) | 1667 (7.7) | 1901 (9.0) |

| 2016 | 7435 (17.1) | 3394 (15.6) | 3850 (18.2) |

| 2017 | 10,969 (25.2) | 5216 (24.0) | 5455 (25.8) |

| 2018 | 12,121 (27.8) | 6219 (28.6) | 5763 (27.3) |

| 2019 | 7437 (17.1) | 4518 (20.8) | 2883 (13.6) |

| Social media platforma | |||

| Tweet | 28,564 (65.6) | 15,420 (71.0) | 12,601 (59.6) |

| Facebook Post | 14,283 (32.8) | 6119 (28.2) | 7995 (37.8) |

| YouTube Video | 629 (1.4) | 128 (0.6) | 501 (2.4) |

| Instagram Post | 81 (0.2) | 52 (0.2) | 29 (0.1) |

| Medium Post | 1 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Legislative divisiona | |||

| Upper house (senate) | 18,783 (43.1) | 8588 (39.5) | 9605 (45.5) |

| Lower house (house of representatives or general assembly) | 24,775 (56.9) | 13,132 (60.5) | 11,521 (54.5) |

aDistributions significantly different between Democrats and Republicans according to chi-squared testing with P<.001

Figure 1.

Log of the total number of opioid-related social media posts overall and by keyword for each calendar quarter from 2014 to 2019.

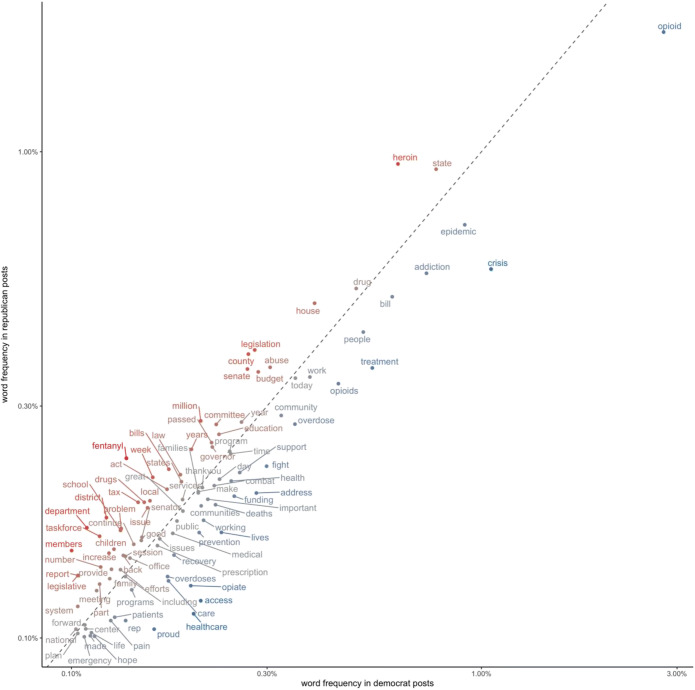

Words more commonly used by Democratic state legislators included “crisis,” “addiction,” “health care,” and “treatment.” Words more commonly used by Republican state legislators included “legislation,” “budget,” “abuse,” “problem,” and “education.” Figure 2 compares the frequency of commonly used words among Democrats and Republicans.

Figure 2.

Comparison of most frequently used words in Democrats’ and Republicans’ opioid-related social media posts.

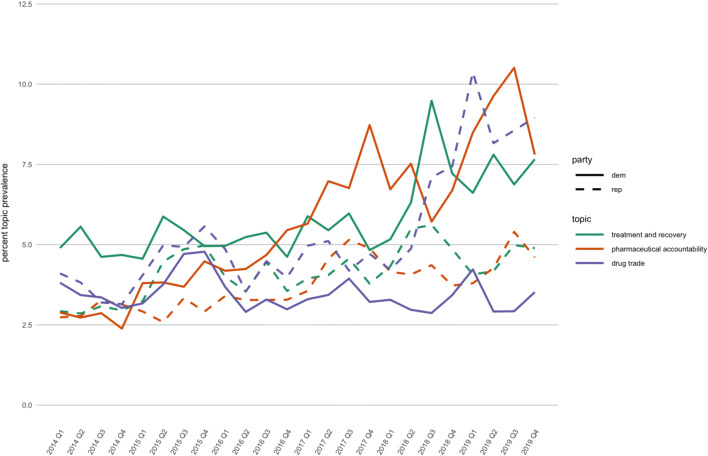

After the removal of hashtags, links, and mentions of other users, 43,080 (98.9%) posts still had text content and were included in the LDA topic analysis. Of 20 LDA topics, authors DCS and AKA agreed on the thematic meaning of 13 (Table 2). Representation of three topics was significantly higher among Republicans’ social media content, as defined by a Wilcoxon signed-rank test P<0.001 with Bonferroni correction (P<5 × 10-5): “drug trade,” “legislative work,” and “local initiatives involving police.” The difference in prevalence between Democrats and Republicans grew dramatically for the topic “drug trade” with posts often referencing the need to control drug trafficking at the US–Mexico border (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Sample Words and Posts for Latent Dirichlet Allocation Topics and Mean Percent Topic Representation Among State Legislators' Posts By Party

| Thematic meaning | Top words | Sample post | Mean percent topic representation among Democrat postsa | Mean percent topic representation among Republican postsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topics significantly more prevalent among Republican postsb | ||||

| Drug trade | Fentanyl, drugs, trafficking, law enforcement, illegal | “Illegal border crossings are set to pass 1 million this year. Smugglers are profiting from trafficking drugs that are contributing to the opioid crisis. Border security is not a "talking point" - it's a matter of national security.” | 3.4% | 5.4% |

| Legislative work | House, committee, legislation, session, bills | “I am thrilled to announce that my legislation …has been signed into law as I included it on Senate Bill 514. This new bipartisan group will include members from both parties in the House and Senate…” | 4.3% | 5.3% |

| Local initiatives involving police | County, district, police, local, chief | “Yesterday, at the Town of Montgomery Police Department, the senator and I presented a check to a community coalition's opioid outreach efforts. Here's how the program works: Any person struggling with addiction can walk into a participating police department and ask for help, and a trained "Angel volunteer will be called to the station to help that person find treatment…” | 4.3% | 5.1% |

| Topics significantly more prevalent among Democrat postsb | ||||

| Pharmaceutical company accountability | Companies, accountable, attorney general, fight, manufacturers | “If you contributed to the problem, you should contribute to the solution. Our bill will make sure companies are held accountable for their part in the opioid crisis, and it will fund treatment and prevention programs to keep our communities safe.” | 6.6% | 3.9% |

| Treatment and recovery | Treatment, addiction, recovery, services, access | “Indiana's Next Level Recovery campaign helps people find reputable addiction treatment, both inpatient, outpatient, residential and opioid treatment programs.” | 6.1% | 4.3% |

| Medical marijuana for alternative pain treatment | Pain, medical marijuana, cannabis, study, patients | “IAGovernor Reynold’s Iowa Medical Cannabidiol Adv Board rejects patient petitions to help PTSD and opioid dependent patients gain access to medical cannabis. Big Pharma loves our Governor and this board!” | 4.9% | 4.1% |

| Overdose deaths and reversal | Overdose, deaths, naloxone, Narcan, people |

“Naloxone is an essential tool for first responders to combat the opioid epidemic. We successfully added ambulance services to the list of entities that are able to purchase naloxone. Now our first responders will be better equipped to fight the crisis on the front lines.” “ |

5.9% | 5.2% |

| Funding | Budget, million, funding, tax, increase | “It's imperative we take action against the #heroin & drug epidemic, which is why we've increased funding by $12M.” | 4.5% | 4.1% |

| Impact on families and communities | Communities, families, crisis, addiction, combat | “Today I participated in the @childhoodleague #annualconference2019 to learn how the opioid crisis affects our kids, families and entire community. Thank you for this wonderful program and all you do to transform challenging starts into unstoppable futures!” | 6.4% | 6.3% |

| Topics not significantly more prevalent among either parties’ postsb | ||||

| Forums and town halls | Forum, event, county, join, awareness | “I’d like to remind you that you are invited to my public forum on heroin and opioid addiction to take place with area law enforcement, health care professionals and drug and addiction specialists... We will discuss ways to work together to combat the epidemic.” | 5.9% | 6.3% |

| Opioid prescribing practices | Prescription, abuse, prescribing, medical, patients | “To help curb the number of unnecessary opioid prescriptions, anyone applying for or renewing their license to prescribe controlled substances will now take additional training courses under a new state law.” | 4.1% | 4.8% |

| Prescription drug takeback programs | Prescription drug, take back, national, unused, abuse | “It will take dedicated partners at every level to reverse the statistics and save lives. We can all start by taking some time today to clean out our medicine cabinets and safely dispose of our unused prescription drugs to keep them off our streets. Click the link below to find a drug drop box near you.” | 3.8% | 4.5% |

| Children and education | School, children, students, education, program | “We need to do all that we can to equip our schools and empower them to keep students safe. #opioids” | 3.5% | 3.8% |

a“Mean percent topic representation” defined as the average topic representation per social media post (normalized such that the total topic distribution for each social media post sums to 100%) across all social media posts for the given party

bSignificance defined by Wilcoxon signed-rank test P<0.001 with Bonferroni correction (P<5 × 10-5)

Figure 3.

Mean percent topic representation by three-month quarter in opioid-related social media posts of Democrat and Republican state legislators between 2014 and 2019. “Mean percent topic representation” was defined as the average topic distribution per social media post (normalized such that the total topic distribution for each social media post sums to 100%) across all social media posts for the given party.

Representation of six topics was significantly higher among Democrats’ social media content: “pharmaceutical company accountability,” “treatment and recovery,” “medical marijuana for alternative pain treatment,” “overdose deaths and reversal,” “funding,” and “impact on families and communities.” The gap in prevalence widened over time for the topics “treatment and recovery” and “pharmaceutical company accountability” (Fig. 3). The remaining topics were not significantly different in representation across parties (Table 2).

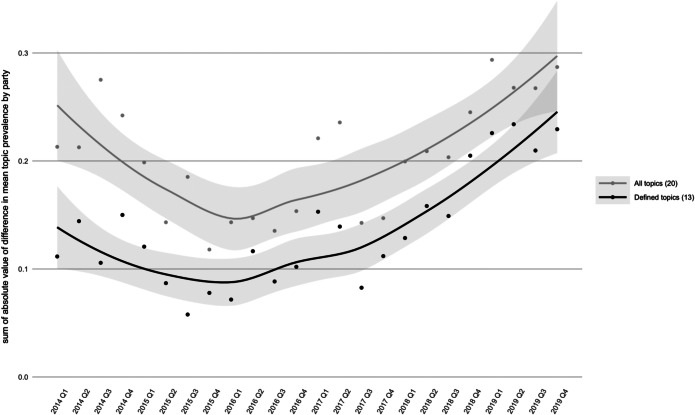

Partisanship in opioid-related social media content, as estimated by the quarterly sum of the absolute difference between Democrats and Republicans in mean topic representation across all topics, declined between 2014 and 2016, before increasing again between 2016 and 2019 (Fig. 4). The longitudinal trends in topic representation and in the partisanship estimate were robust to exclusion of retweets and other duplicate posts (Online Appendix).

Figure 4.

Partisanship in opioid-related social media content as estimated by the quarterly sum across all topics of the absolute difference between Democrats’ and Republicans’ mean topic representation in social media posts. Topic representation (and therefore mean topic representation) ranges from 0 to 1, and the sum of absolute differences therefore theoretically ranges from 0 to the number of topics (13 or 20).

DISCUSSION

This study applied natural language processing to identify important themes and longitudinal changes in partisanship in the opioid-related social media content of state legislators. It has three key findings. First, state legislators are actively using social media to discuss the opioid epidemic, and the volume and language of their social media content are consistent with trends in overdose mortality. Second, some topics related to evidence-based interventions, e.g., “treatment and recovery,” were not equally represented among the parties’ social media posts, while others were e.g. regulations regarding “opioid prescribing.” Third, longitudinal trends indicate that the gap between Democrats and Republicans on key opioid-related topics is growing, particularly in the areas of pharmaceutical accountability, treatment of those with opioid use disorder, and stemming the illicit manufacture and trade of opioids. Addressing the opioid epidemic is a priority across the nation, but the two parties appear to be trending increasingly away from a consensus approach.11

State legislators are increasingly utilizing social media as a platform to discuss the opioid epidemic. Both Democrats and Republicans published over 20,000 posts mentioning opioids between 2014 and 2019, and over two-thirds of posts were published in the final 3 years. The majority of the opioid-related content was posted to Facebook and Twitter, the most popular social media platforms in the USA.33 The posts were consistent with national- and state-level trends in opioid mortality in several ways: legislators’ increasingly used the word “fentanyl,” rather than “heroin,” mirroring synthetic opioids’ growing share of overdose mortality, and the association between the number of opioid-related social media posts and overdose mortality in legislators’ home states was consistent across Democrats and Republicans.1

The topics and words that legislators used more frequently were notably different, including in their emphasis on potentially evidence-based policy interventions. Among Democrats, greater representation of the topics “treatment and recovery” and “overdose deaths and reversal” may reflect support for treating opioid use disorder as an illness. While some forms of medical treatment are associated with decreased overdose mortality, including medication treatment with methadone, suboxone, and naltrexone and overdose reversal with naloxone, others, such as inpatient detox, are not.6, 9, 34 Prior research has shown that Republican-controlled states are more likely to pursue treatment expansion covertly, in order to avoid endorsing Medicaid expansion.11 Consistent with those findings, posts highly represented by the topic “local initiatives involving police,” a topic more common to Republican content, often referred to programs in which police were involved in connecting people to treatment, as in the example in Table 2, or in administering naloxone; an Ohio-based study found that training police officers to administer naloxone was associated with fewer opioid overdose deaths locally.35 These results justify future studies explicitly examining legislators’ posts about medication treatment for opioid use disorder and naloxone for overdose reversal. Both parties spoke equally to the regulation of prescription drugs, another evidence-based intervention.36

Differences in opioid-related topic emphasis by party have grown steadily since a nadir in the 4th quarter of 2015, which may signal a widening gap in Democrats' and Republicans' priorities related to the opioid epidemic. On social media, Democrats’ increasing focus on pharmaceutical company litigation is sometimes, though not always, linked to funding potentially evidence-based interventions, as in the example provided in Table 2.37 Whether “treatment” refers to effective interventions, like medication treatment, or ineffective ones, like inpatient detox, however, is unclear. Since the beginning of 2017, Republicans’ social media has increasingly focused on the “drug trade,” both internationally and locally. A focus on curbing drug-related crimes may dissuade some illegal opioid sales, but it may also have unintended consequences. For instance, one study of New York City precincts found that increased rates of misdemeanor arrests were associated with higher overdose rates.38 Arrests for drug-related crimes are also made unequally: in 2014, Black and Latinx men in the USA were five times and two times more likely than white men to be imprisoned for drug-related crimes, respectively, despite comparable rates of drug use across all three groups.39 A focus on preventing drug-related crime contributes to a culture of criminalizing, rather than treating, substance use disorders.

This is the first study to use natural language processing of state legislators’ social media content to measure and describe partisanship around an issue over time. State legislators’ word choices on social media carry influence. They can reflect both the changing public landscape, as in more frequent mentions of fentanyl, and changing legislative priorities, as in more mentions of suing pharmaceutical companies. Word choice can also either challenge or propagate stigma. Democrats and Republicans both used the stigmatizing word “abuse” relatively frequently in opioid-related posts.16 Anti-stigma training among state legislators may lead to more appropriate language choices and down-stream reductions in stigma among constituents.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. We were unable to control for years in office in our measures of legislators’ number of opioid-related social media posts, as Quorum reports only whether an individual is a current or former legislator at the time of data download. We also did not have access to the total number of social media posts for each legislator and were therefore unable to control for a legislators’ general social media activity. These limitations did not affect our measures of the use of opioid-related topics over time; however, as these were specific to the use among opioid-related social media posts, not all social media posts.

In our language analysis, we considered single words and several two-word phrases, as described in the Online Appendix, but we did not account for context or sentiment. We were therefore able to speak to the prevalence of words or topics, but not to whether they were being endorsed or criticized.

We measured partisanship nationally, rather than at the state level, and we gave equal weight to posts from legislators in their states’ majority or minority party. Future analyses may look to the impact that state house or senate control has on the partisanship of legislators’ posts.

Legislators who use social media are not representative of all legislators, and as such, measures of topic representation and partisanship among social media posts over time do not necessarily reflect trends across the Democratic and Republican parties more broadly. For instance, social media use may select for younger or more argumentative legislators. Our analyses are, however, representative of the social media content generated by state legislators with which the public engages, which may affect public sentiment.

Finally, social media language does not necessarily lead to specific votes or policy decisions. Identifying relationships between state legislator social media content and state legislator voting patterns was beyond the scope of this project.

Conclusion

Social media can provide valuable insight into trends in state legislators’ opioid-related talking points. We demonstrate a growing divide between Democrats and Republicans. Democrats increasingly posted content related to pharmaceutical company litigation, and Republicans increasingly posted content related to curbing the drug trade. Neither approach is directly focused on treatment, and the latter approach may lead to greater morbidity and mortality, especially among marginalized communities, through further criminalization of opioid use disorder.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 232091 kb)

Acknowledgements

Support for this project, including through data acquisition, was provided by the Center for Health Economics of Treatment Interventions for Substance Use Disorder, HCV, and HIV (CHERISH), a National Institute on Drug Abuse research center (P30 DA040500) and in partnership with the Research-to-Policy Collaboration, affiliated with The Pennsylvania State University's Edna Bennett Pierce Prevention Research Center.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ahmad, FB, Rossen, LM, Sutton, P.Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts. National Center for Health Statistics; 2020. Accessed July 11, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

- 2.Jones CM, Einstein EB, Compton WM. Changes in Synthetic Opioid Involvement in Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 2010-2016. JAMA. 2018;319(17):1819–1821. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.2844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoots B, Vivolo-Kantor A, Seth P. The rise in non-fatal and fatal overdoses involving stimulants with and without opioids in the United States. Addict Abingdon Engl. 2020;115(5):946–958. doi: 10.1111/add.14878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dowell D, Zhang K, Noonan RK, Hockenberry JM. Mandatory Provider Review And Pain Clinic Laws Reduce The Amounts Of Opioids Prescribed And Overdose Death Rates. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2016;35(10):1876–1883. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kennedy-Hendricks A, Richey M, McGinty EE, Stuart EA, Barry CL, Webster DW. Opioid Overdose Deaths and Florida’s Crackdown on Pill Mills. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(2):291–297. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walley AY, Lodi S, Li Y, et al. Association between mortality rates and medication and residential treatment after in-patient medically managed opioid withdrawal: a cohort analysis. Addiction. Published online February 25, 2020. 10.1111/add.14964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Krawczyk N, Mojtabai R, Stuart EA, et al. Opioid agonist treatment and fatal overdose risk in a state-wide US population receiving opioid use disorder services. Addiction. Published online February 24, 2020. 10.1111/add.14991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Abouk R, Pacula RL, Powell D. Association Between State Laws Facilitating Pharmacy Distribution of Naloxone and Risk of Fatal Overdose. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(6):805–811. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smart R, Pardo B, Davis CS. Systematic review of the emerging literature on the effectiveness of naloxone access laws in the United States. Addiction. n/a(n/a). 10.1111/add.15163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Goodwin JS, Kuo Y-F, Brown D, Juurlink D, Raji M. Association of Chronic Opioid Use With Presidential Voting Patterns in US Counties in 2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(2):e180450–e180450. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grogan CM, Bersamira CS, Singer PM, et al. Are Policy Strategies for Addressing the Opioid Epidemic Partisan? A View from the States. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2020;45(2):277–309. doi: 10.1215/03616878-8004886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nelson KL, Purtle J. Factors associated with state legislators’ support for opioid use disorder parity laws. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;82:102792. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kennedy-Hendricks A, Levin J, Stone E, McGinty EE, Gollust SE, Barry CL. News Media Reporting On Medication Treatment For Opioid Use Disorder Amid The Opioid Epidemic. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(4):643–651. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGinty EE, Barry CL, Stone EM, et al. Public support for safe consumption sites and syringe services programs to combat the opioid epidemic. Prev Med. 2018;111:73–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL, Gollust SE, Ensminger ME, Chisolm MS, McGinty EE. Social Stigma Toward Persons With Prescription Opioid Use Disorder: Associations With Public Support for Punitive and Public Health-Oriented Policies. Psychiatr Serv Wash DC. 2017;68(5):462–469. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201600056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGinty EE, Stone EM, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL. Stigmatizing language in news media coverage of the opioid epidemic: Implications for public health. Prev Med. 2019;124:110–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hemphill L, Russell A, Schöpke-Gonzalez AM. What Drives U.S. Congressional Members’ Policy Attention on Twitter? Policy Internet. n/a(n/a). 10.1002/poi3.245

- 18.BarberÁ P, Casas A, Nagler J, et al. Who Leads? Who Follows? Measuring Issue Attention and Agenda Setting by Legislators and the Mass Public Using Social Media Data. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2019;113(4):883–901. doi: 10.1017/S0003055419000352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook JM. Are American Politicians as Partisan Online as They are Offline? Twitter Networks in the U.S. Senate and Maine State Legislature. Policy Internet. 2016;8(1):55–71. doi: 10.1002/poi3.109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Opioid Overdose: Opioid Basics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published March 19, 2020. Accessed June 26, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/opioids/index.html

- 21.State Partisan Composition. National Conference of State Legislatures. Published March 31, 2020. Accessed June 26, 2020. https://www.ncsl.org/research/about-state-legislatures/partisan-composition.aspx

- 22.CDC WONDER. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published February 26, 2020. Accessed June 15, 2020. https://wonder.cdc.gov/

- 23.Blei DM, Ng AY, Jordan MI. Latent Dirichlet Allocation. J Mach Learn Res. 2003;3(January):993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Julia Silge, David Robinson.Text Mining with R - A Tidy Approach. O’Reilly Media Inc.; 2020. https://www.tidytextmining.com/

- 25.Agarwal AK, Wong V, Pelullo AM, et al. Online Reviews of Specialized Drug Treatment Facilities-Identifying Potential Drivers of High and Low Patient Satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1647–1653. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05548-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ranard BL, Werner RM, Antanavicius T, et al. Yelp Reviews Of Hospital Care Can Supplement And Inform Traditional Surveys Of The Patient Experience Of Care. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2016;35(4):697–705. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwartz HA, Ungar LH. Data-Driven Content Analysis of Social Media: A Systematic Overview of Automated Methods. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2015;659(1):78–94. doi: 10.1177/0002716215569197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kern ML, Eichstaedt JC, Schwartz HA, et al. From “Sooo excited!!!” to “So proud”: using language to study development. Dev Psychol. 2014;50(1):178–188. doi: 10.1037/a0035048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stokes DC, Andy A, Guntuku SC, Ungar LH, Merchant RM. Public Priorities and Concerns Regarding COVID-19 in an Online Discussion Forum: Longitudinal Topic Modeling. J Gen Intern Med. Published online May 12, 2020. 10.1007/s11606-020-05889-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Griffiths TL, Steyvers M. Finding scientific topics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(Suppl 1):5228–5235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307752101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang L, Lakin J, Riley C, Korach Z, Frain LN, Zhou L. Disease Trajectories and End-of-Life Care for Dementias: Latent Topic Modeling and Trend Analysis Using Clinical Notes. AMIA Annu Symp Proc AMIA Symp. 2018;2018:1056–1065. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2019. https://www.R-project.org/

- 33.Perrin A, Anderson M. Share of U.S. adults using social media, including Facebook, is mostly unchanged since 2018. Pew Research Center. Published April 10, 2019. Accessed July 15, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/10/share-of-u-s-adults-using-social-media-including-facebook-is-mostly-unchanged-since-2018/

- 34.Wakeman SE, Larochelle MR, Ameli O, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Different Treatment Pathways for Opioid Use Disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1920622–e1920622. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rando J, Broering D, Olson JE, Marco C, Evans SB. Intranasal naloxone administration by police first responders is associated with decreased opioid overdose deaths. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(9):1201–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pardo B. Do more robust prescription drug monitoring programs reduce prescription opioid overdose? Addiction. 2017;112(10):1773–1783. doi: 10.1111/add.13741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Your Guide To The Massive (And Massively Complex) Opioid Litigation. NPR.org. Accessed July 13, 2020. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/10/15/761537367/your-guide-to-the-massive-and-massively-complex-opioid-litigation

- 38.Bohnert ASB, Nandi A, Tracy M, et al. Policing and risk of overdose mortality in urban neighborhoods. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;113(1):62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Csete J, Kamarulzaman A, Kazatchkine M, et al. Public health and international drug policy. The Lancet. 2016;387(10026):1427–1480. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00619-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 232091 kb)