Abstract

Systemic sclerosis is a connective tissue disease with cutaneous involvement. Clinical manifestations result from the balance of inflammations/autoimmunity process and fibrogenesis. Patients suffer from skin ulcers, non-ulcerative lesions including digital pitting scars, telangiectasias, subungual hyperkeratosis, abrasions, fissures, and subcutaneous calcinosis. A review about the pathophysiology of the disease, the physical examination of the patients, the instrumental assessment, and possible treatments is performed.

Keywords: Skin fibrosis, Digital ulcers, Scleroderma, Systemic sclerosis, Autologous fat grafting

Keywords: SSc, Systemic sclerosis; SU, skin ulcer; DU, digital ulcer; RP, Raynaud's phenomenon; MHISS, Mouth Handicap in Systemic Sclerosis scale; ROM, Range of Motion

Highlights

-

•

Sistemic sclerosis is a connective tissue disease with cutaneous involvement.

-

•

Digital ulcers involve hands, feet, bony prominence and lower limbs.

-

•

Skin is the window of the disease: if skin conditions worsen, an aggravation of systemic involvement can be suspected.

-

•

Fat grafting represents an innovative technique promoting a faster wound healing.

1. Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a connective tissue disease, characterized by vascular dysfunction, abnormal fibroblast activation and antibodies production, with cutaneous and visceral involvement [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5]]. Several clinical manifestations are described, including skin fibrosis (diffuse cutaneous or limited SSc), digital ulcers [6], pulmonary involvement (interstitial lung disease) [6,7], pulmonary hypertension [[8], [9], [10]], cardiac [[11], [12], [13]], renal, gastro-intestinal involvement and arthritis [14]. Due to cardiac and pulmonary; complications, prognosis can be severe [7,8,11].

2. Pathophysiology

Clinical and serological SSc phenotype result from a complex interaction of multiple factors in genetically predispose subjects. B-cell and T-cell activation, altered fibroblast activity and microangiopathy resulting from endothelial dysfunction are the main pathogenetic features [15,16]. Moreover, genetic human leukocyte antigen alterations, viral infections such as Parvovirus B19 and Cytomegalovirus [[17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22]] in addition to environmental toxins [23] seem to be triggers of the disease. Indeed, autonomic dysfunction may also play a role in the SSc pathogenesis [24]. Clinical manifestations result from the balance of inflammations/autoimmunity process and fibrogenesis. In a set of vascular deregulation tissue damage; mediated by some vascular elements such as endothelial growth factor, endothelin 1, platelet derived growth; factor, fibroblast growth factor b, produce fibroblasts and leukocytes recruitment. Regulatory T cells, T-helper 2 and T-helper 1 cells interact with fibroblast cell line leading to myofibroblast production of Extracellular matrix (ECM) with overexpression of collagen, responsible for tissue remodelling and fibrosis, with evidence of tumor necrosis factor α and chemokine alterations [[25], [26], [27], [28]]. Endothelial-mesenchymal transition may be a crucial event linking endothelial dysfunction and development of dermal fibrosis [29]. Vasculopathy is considered a cardinal feature of SSc complications. Platelet activations, aggregation and thrombotic events are related to severe organ complications such as digital ulcer, pulmonary hypertension and scleroderma renal crisis. Vascular pathological changes such as intimal hyperplasia, adventitial fibrosis and compromised lumen can be found [30]. It is interesting how SSc shares with COVID-19 a possible common pathogenetical mechanism, including ILD evolution to fibrosis, endothelial damage and consequent diffuse microangiopathy [[31], [32], [33], [34], [35]].

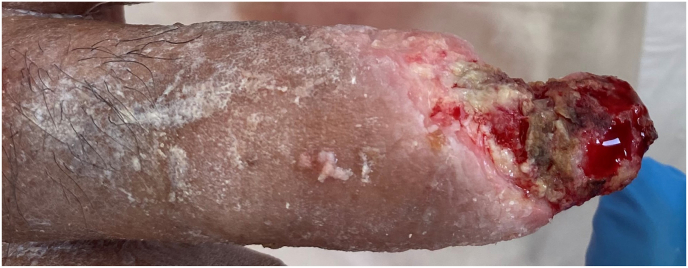

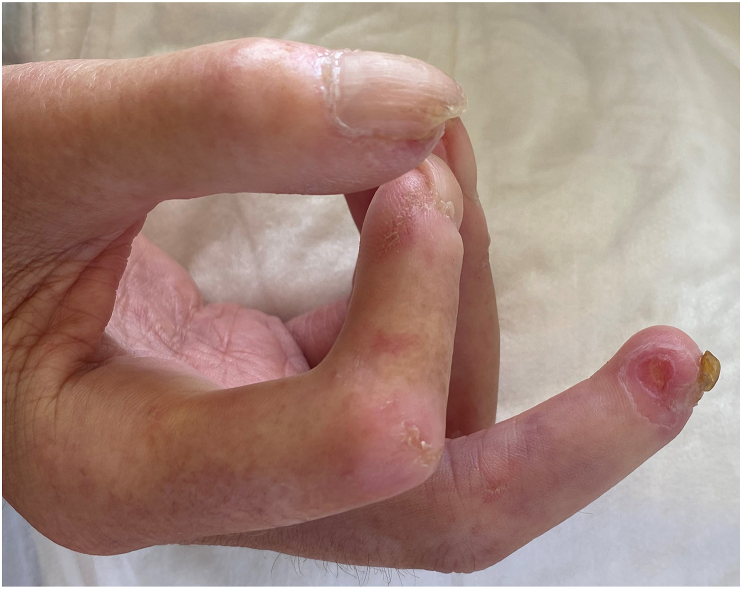

3. Physical examination

During physical examination cutaneous involvement must be assessed, starting from the presence of skin ulcers (SU). SU can be classified as digital ulcers (DU) of hands (Fig. 1) and feet, SU of bony prominence (Fig. 2), SU on calcinosis, SU of lower limbs, DU/SU with gangrene (Fig. 3) [36]. SU is firstly evaluated according to triangle wound assessment, considering wound bed (tissue type, exudate, infection), wound edge (maceration, dehydration, undermining, rolled), peri wound skin (maceration, excoriation, dry skin, hyperkeratosis, callus, eczema) [37]. DU represent one of the most recurrent SSc complications, associated with limited daily activity [38]. Moreover, osteomyelitis may complicate DU infection [38,39] leading to amputation and morbidity. In addition, the presence of non-ulcerative lesions including digital pitting scars, telangiectasias, subungual hyperkeratosis, abrasions, fissures and subcutaneous calcinosis should be taken into consideration [6,36]. Edematous feature of the hands is described as “puffy hands” (Fig. 4), and reflects an active stage of disease, previous to fibrotic degeneration. On the other hand, advanced fibrotic involvement of the fingers is defined sclerodactyly (Fig. 5). Microstomia can be appreciated when oral rhyme is reduced and thinned, limiting jaw opening; angular cheilitis may be a microstomia complication (Fig. 6, Fig. 7). Diffuse hyper melanosis of the skin is addressed as melanodermia [6]. Morphea consists in localized scleroderma and is considered as a different condition, although evolution from localized to systemic disease is possible [4]. OBJECTIVE SCALES Skin thickness can be evaluated performing the modified Rodnann skin score. Total score is calculated assigning score values from 0 to 3 for each body area (fingers, hands, forearms, upper arms, face, anterior chest, abdomen, thighs, legs and feet). 0 for normal skin (fine wrinkles appreciable); 1 for mild skin thickness (skin folds between the examiner's fingers, fine wrinkles are acceptable); 2 for moderate skin thickness (difficulty in skin folding and no appreciable wrinkles); 3 when severe skin thickness is present (complete impossibility in skin folding between examiner's fingers). Total score is obtained adding single scores for all the body areas assessed [40].

Fig. 1.

Purulent exudate before sharp debridement.

Fig. 2.

Bleeding Ulcer after sharp debridement.

Fig. 3.

Acral digital necrosis and gangrene.

Fig. 4.

Puffy hands.

Fig. 5.

Sclerodactyly and digital ulcer.

Fig. 6.

Sclerodactyly and digital ulcer.

Fig. 7.

Microstomia complicated by angular cheilitis.

4. Subjective scales

Raynaud's phenomenon (RP) can be assessed using a 0–10 ordinal scale. The Raynaud Condition Scale (RCS), considers frequency, duration, intensity and impact of RP episodes. Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) is useful to measure patients' self-reported function. Each question can be scored scored 0–3 (where 0 = without difficulty and 3 = unable to do). The questions investigate patients' ability regarding several domains such as dressing and grooming, arising, eating, walking, hygiene, reach, grip and common daily activities. The maximum score reported from each category is added together and divided by the number of completed categories. An extra point can be added, to a maximum of 3, for each category if the need of aids/devices is reported. Whereas for a maximum score [3], it cannot be increased [41]. Functional disability scales include the Durouz's Hand Index (DHI) and the Mouth Handicap in Systemic Sclerosis scale (MHISS). DHI is a self-administered questionnaire that evaluates hand function during daily activities of living (DAL) through 18 items. Each item can be scored 0–5: 0 corresponds to no difficulty at all, while 5 means patient's inability to complete the action. The final obtained score with this scale was proven to be a reliable and valid tool for SSc evaluation from clinical course, therapeutic intervention outcome, to analysis and prognosis evaluation [42]. Similarly, MHISS is a questionnaire where patients are asked to answer 12 questions investigating mouth involvement in SSc, giving a score from 0 to 4 to each of them [43]. Pain is commonly reported by SSc patients and it can be investigated through both unidimensional and multi-dimensional scales. The Visual Analog Scale (VAS) is the visual representation of the perceived pain by the patient on a 10 cm-long line, where the two extremities correspond to no pain at all on one side, and unbearable pain on the other side. The Short Form McGill Pain Questionnaire is instead a validated self-reported pain measure, assessing both quality and intensity of pain including 15 descriptors of pain (0–4 score) [44].

5. Objective assessment

Nailfold capillaroscopy allows to evaluate microangiopathy features, highlighting vascular morphological abnormalities such as enlarged, giant-bushy capillaries, microhaemorrhages, variable loss of capillaries and vascular desertification. Capillaroscopic findings vary according to different stage of disease and could predict the risk of future complications such as digital ulcers [[45], [46], [47], [48], [49]]. Hands' Range of Motion (ROM) can be estimated using a small-joints-specific goniometer with a 180°' quadrant through a dorsal positioning. The articular angles of motion are measured, and limitation reflects disease severity and progression [50]. Typically, SSc-associated ROM limitations include loss of flexion of metacarpophalangeal joints, loss of extension of proximal interphalangeal joints and loss of thumb abduction, opposition, and flexion. Another approach consists in measuring the distance between the middle finger and the palm, reflecting patient's inability to make a fist [50]. In addition to hand function loss, strength decrease can be observed in around 90% of SSc patients [50]. Jamar Dynamometer is a validated tool used to measure grasp static force using 5 different handle widths ranging from 3.5 to 8.8 cm: the first 3 positions test the involvement of hand intrinsic and extrinsic flexors, the last 2 evaluate mainly extrinsic flexors action. An average value among three measures for each position is recorded to obtain an accurate report. Jamar Pinch-Gauges instead, evaluates pinch force. Three different specific positions involving the thumb and the index and middle finger of the hand are involved: the key pinch, the three-jaw pinch and tip to tip pinch [50]. Semmest-Weistein monofilament test is used to assess the threshold for response to tactile stimuli on different hands' locations. The test consists of five filaments with different thickness, the patient is asked to identify when applied on the skin, starting from the finest filament. This allows to estimate tactile sensation deficits also from a quantitative point of view. The static two-points discrimination test is instead employed to test functional sensibility asking the patient to recognize as different two close stimuli applied on a small area of the skin. Normal sensibility corresponds to a two-point-distance less than 6 mm.

6. Local treatment

For DU wound bed preparation should be approached considering the acronym TIME (necrotic Tissue, Infection and inflammation, Moisture balance, Epithelization). A sharp wound debridement should be performed, allowing the removal of damaged tissue and reducing bacterial load. Wound swab can be performed if signs of inflammation and infection are noted [36]. Advanced techniques of wound dressing include the use of alginate, hydrocolloid, hydrofiber, hydrogel for autolytic debridement and polyurethane foam or film, to ensure a proper moisture balance, accelerating wound healing, to a complete reepithelization [36]. A proper pain management is mandatory for both background and procedural pain while performing sharp debridement [[51], [52], [53], [54]]. The use of Hypericum perforatum and neem oil has been proved effective for the treatment of subcutaneous calcinosis [55] and hypercheratosis. For SU scarcely responsive to traditional treatments, regenerative medicine options are available. Local approach using autologous skin grafting and homologous platelet gel has been described [56,57]. The implantation of autologous mesenchimal stem cells derived from adipose tissue represent an innovative technique promoting a faster wound healing [[58], [59], [60], [61]].

7. Systemic treatment

Following the EULAR recommendations for the treatment of SSc vasculopathy, calcium channel blockers represent the first line treatment [65]. Periodic Iloprost intravenous infusions are recommended for the healing of DU together with oral Phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors [[65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70]]. Endothelin receptor antagonists are also used to prevent the occurrence of DU [65]. Among systemic treatments, Rituximab (RTX) improves cutaneous and articular manifestations, moderating also lung fibrotic involvement [71]. The use of growth factors such as recombinant human erythropoietin and granulocytes colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) could be proposed for the treatment of obstinate SU healing [72,73]. Systemic pain treatment is fundamental in SSc cutaneous expressions as previously described [52].

7.1. Autologous fat grafting

Furthermore, autologous fat grafting seems to be a new promising approach in the management of SS cutaneous manifestations. Fat tissue can be harvested under local anaesthesia through the Coleman's technique, then adipose tissue-derived stem cells (ATSC) can be obtained and grafted on different body locations as the perioral region or the hands [[58], [74], [75], [76]]. It was demonstrated that ATSC have proangiogenic activity, immunosuppressive properties, and differentiation potential. The positive effect of fat tissue grafting on overall tissue quality, results in improvement and slowdown of SSc complications such as microstomia, xerostomia, skin sclerosis, Raynaud's phenomenon, and long-lasting digital ulcers [58].

8. Anesthesiological considerations

Patients with SSc presenting for even minimal surgery requesting moderate sedation to general anaesthesia can be challenging for every anaesthesiologist [62]. Adequate preoperative evaluation should quantify extent and severity of SSc related disease and perioperative possible complications in order to properly plan the optimal technique. Systemic comorbidities such as interstitial lung disease, pulmonary arterial hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and kidney failure are often present at the same time and must be considered together with difficult airway management [63]. A high psychiatric burden is also observed in these patients: depression and anxiety above all. These conditions together with a history of severe chronic pain make even the local anaesthesia procedure more difficult than usual. The collaboration inside Surgical teams of skilled anaesthesiologists together with newer patient-tailored techniques such as Target Control Infusion (TCI) and proper intraoperative monitoring can be the first choice for moderate sedation in most common cutaneous surgical procedures on SSc patients [64].

9. Patient management in scleroderma unit

A close collaboration between different specialists is essential for the management of patients with cutaneous expressions of SSc. The role of the rheumatologist is the control of the disease throughout systemic and local treatments. Moreover, a strict follow-up of the patient is crucial to note and promptly treat cutaneous changes. Skin ulcers must be treated by well-skilled healthcare assistants according to physician's advice. The role of the plastic surgeon is to identify the patient which can take advantages from the autologous fat grafting both for the prevention and treatment of SU. SSc has a great impact on the psychophysical and emotional sphere of the patient that explains the fundamental role of the psychologist. Skilled anesthesiologists are important for the control of pain during the surgical treatment.

10. Conclusion

Cutaneous involvement assessment is fundamental to perform the more appropriate treatment. Measurements of skin conditions throughout scales and instruments is essential to monitor the ongoing therapy. Skin ulcers can be treated throughout debridement and advanced techniques of wound dressings. Systemic treatment is helpful not only for the treatment of the cutaneous manifestations of SSc but also for the prevention. Skin could be considered a window of the disease: if skin conditions worsen, an aggravation of cardiac and pulmonary involvement can be suspected. Autologous fat grafting seems to be an effective approach in the management of the cutaneous manifestations of the disease. Nevertheless, a close collaboration between rheumatologists and plastic surgeons is mandatory to individualize patients that can benefit from autologous fat grafting. This review can be helpful for young doctors without a great experience to understand how to manage this disease. A constant updating represents the milestone of the best treatment.

Ethical approval

Nothing to declare.

Sources of funding

Nothing to declare.

Author contribution

Marta Starnoni: study concept, data interpretation. Marco Pappalardo: data collection. Amelia Spinella: data collection. Sofia Testoni: study concept, data interpretation, writing the paper. Melba Lattanzi: data interpretation, writing the paper. Raimondo Feminò: data interpretation, writing the paper. Giorgio De Santis: data interpretation. Carlo Salvarani: data interpretation. Dilia Giuggioli: study concept, data interpretation.

Registration of research studies

The research does not involve human participants but it is a review of the literature.

Guarantor

Giorgio De Santis; Dilia Giuggioli.

Trial registry number

Nothing to declare.

Consent

The study is a review of the literature.

Patients have given consent for possible publication of images.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declares that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Giuggioli D., Manfredi A., Colaci M., Manzini C.U., Antonelli A., Ferri C. Systemic sclerosis and cryoglobulinemia: our experience with overlapping syndrome of scleroderma and severe cryoglobulinemic vasculitis and review of the literature. Autoimmun Rev. 2013 Sep;12(11):1058–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferri C., Sebastiani M., Lo Monaco A., Iudici M., Giuggioli D., Furini F., et al. Systemic sclerosis evolution of disease pathomorphosis and survival. Our experience on Italian patients' population and review of the literature. Autoimmun Rev. 2014 Oct;13(10):1026–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferri C., Giuggioli D., Guiducci S., Lumetti F., Bajocchi G., Magnani L., et al. Systemic sclerosis Progression INvestiGation (SPRING) Italian registry: demographic and clinico-serological features of the scleroderma spectrum. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020 Jun;38(Suppl 125):40–47. (3) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giuggioli D., Colaci M., Cocchiara E., Spinella A., Lumetti F., Ferri C. From localized scleroderma to systemic sclerosis: coexistence or possible evolution. Dermatol Res Pract. 2018;2018:1284687. doi: 10.1155/2018/1284687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fallahi P., Ruffilli I., Giuggioli D., Colaci M., Ferrari S.M., Antonelli A., et al. Associations between systemic sclerosis and thyroid diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2017 Oct 3;8:266. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferri C., Valentini G., Cozzi F., Sebastiani M., Michelassi C., La Montagna G., et al. Systemic sclerosis: demographic, clinical, and serologic features and survival in 1,012 Italian patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002 Mar;81(2):139–153. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200203000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ariani A., Silva M., Bravi E., Parisi S., Saracco M., De Gennaro F., et al. Overall mortality in combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema related to systemic sclerosis. RMD Open. 2019;5(1) doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giuggioli D., Bruni C., Cacciapaglia F., Dardi F., De Cata A., Del Papa N., et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: guidelines and unmet clinical needs. Reumatismo. 2021 Jan 18;72(4):228–246. doi: 10.4081/reumatismo.2020.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iudici M., Codullo V., Giuggioli D., Riccieri V., Cuomo G., Breda S., et al. Pulmonary hypertension in systemic sclerosis: prevalence, incidence and predictive factors in a large multicentric Italian cohort. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2013 Apr;31(2 Suppl 76):31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Occhipinti M., Bruni C., Camiciottoli G., Bartolucci M., Bellando-Randone S., Bassetto A., et al. Quantitative analysis of pulmonary vasculature in systemic sclerosis at spirometry-gated chest CT. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2020 Sep 1;79(9):1210–1217. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coppi F., Giuggioli D., Spinella A., Colaci M., Lumetti F., Farinetti A., et al. Cardiac involvement in systemic sclerosis: identification of high-risk patient profiles in different patterns of clinical presentation. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2018 Jul;19(7):393–395. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferri C., Giuggioli D., Sebastiani M., Colaci M., Emdin M. Heart involvement and systemic sclerosis. Lupus. 2005;14(9):702–707. doi: 10.1191/0961203305lu2204oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spinella A., Coppi F., Mattioli A.V., Lumetti F., Rossi R., Cocchiara E., et al. Management of cardiopulmonary disease in patients with systemic sclerosis: cardiorheumatology clinic and patient care standardization proposal. Journal of Cardiovascular Medicine. 2018 Sep;19(9):513–515. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denton C.P., Khanna D. Systemic sclerosis. Lancet. 2017 Oct 7;390(10103):1685–1699. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30933-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown M., O'Reilly S. The immunopathogenesis of fibrosis in systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2019 Mar;195(3):310–321. doi: 10.1111/cei.13238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cutolo M., Soldano S., Smith V. Pathophysiology of systemic sclerosis: current understanding and new insights. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2019 Jul;15(7):753–764. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2019.1614915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arcangeletti M.-C., Maccari C., Vescovini R., Volpi R., Giuggioli D., Sighinolfi G., et al. A paradigmatic interplay between human Cytomegalovirus and host immune system: possible involvement of viral antigen-driven CD8+ T cell responses in systemic sclerosis. Viruses. 2018 Sep 18;10(9):E508. doi: 10.3390/v10090508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zakrzewska K., Arvia R., Torcia M.G., Clemente A.M., Tanturli M., Castronovo G., et al. Effects of Parvovirus B19 in vitro infection on monocytes from patients with systemic sclerosis: enhanced inflammatory pathways by caspase-1 activation and cytokine production. J Invest Dermatol. 2019 Oct;139(10):2125–2133.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.03.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caselli E., Soffritti I., D'Accolti M., Bortolotti D., Rizzo R., Sighinolfi G., et al. HHV-6A infection and systemic sclerosis: clues of a possible association. Microorganisms. 2019 Dec 24;8(1):E39. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8010039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Human Parvovirus B19 (B19V) Infection . vol. 52. Karger Publishers; 2009. (Systemic Sclerosis Patients - Abstract - Intervirology). No. 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magro C.M., Nuovo G., Ferri C., Crowson A.N., Giuggioli D., Sebastiani M. Parvoviral infection of endothelial cells and stromal fibroblasts: a possible pathogenetic role in scleroderma. J Cutan Pathol. 2004 Jan;31(1):43–50. doi: 10.1046/j.0303-6987.2003.0143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferri C., Zakrzewska K., Longombardo G., Giuggioli D., Storino F.A., Pasero G., et al. Parvovirus B19 infection of bone marrow in systemic sclerosis patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1999 Dec;17(6):718–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferri C., Artoni E., Sighinolfi G.L., Luppi F., Zelent G., Colaci M., et al. High serum levels of silica nanoparticles in systemic sclerosis patients with occupational exposure: possible pathogenetic role in disease phenotypes. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018 Dec;48(3):475–481. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferri C., Emdin M., Giuggioli D., Carpeggiani C., Maielli M., Varga A., et al. Autonomic dysfunction in systemic sclerosis: time and frequency domain 24 hour heart rate variability analysis. Br J Rheumatol. 1997 Jun;36(6):669–676. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/36.6.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Denton C.P., Black C.M., Abraham D.J. Mechanisms and consequences of fibrosis in systemic sclerosis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2006 Mar;2(3):134–144. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mostmans Y., Cutolo M., Giddelo C., Decuman S., Melsens K., Declercq H., et al. The role of endothelial cells in the vasculopathy of systemic sclerosis: a systematic review. Autoimmun Rev. 2017 Aug;16(8):774–786. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2017.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antonelli A., Fallahi P., Ferrari S.M., Giuggioli D., Colaci M., Di Domenicantonio A., et al. Systemic sclerosis fibroblasts show specific alterations of interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α-induced modulation of interleukin 6 and chemokine ligand 2. J Rheumatol. 2012 May;39(5):979–985. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.111132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antonelli A., Ferri C., Fallahi P., Ferrari S.M., Giuggioli D., Colaci M., et al. CXCL10 (alpha) and CCL2 (beta) chemokines in systemic sclerosis--a longitudinal study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008 Jan;47(1):45–49. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manetti M., Romano E., Rosa I., Guiducci S., Bellando-Randone S., De Paulis A., et al. Endothelial-tomesenchymal transition contributes to endothelial dysfunction and dermal fibrosis in systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 May;76(5):924–934. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jinnin M. ‘Narrow-sense’ and ‘broad-sense’ vascular abnormalities of systemic sclerosis. Immunol Med. 2020 Sep;43(3):107–114. doi: 10.1080/25785826.2020.1754692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferri C., Giuggioli D., Raimondo V., Dagna L., Riccieri V., Zanatta E., et al. COVID-19 and systemic sclerosis: clinicopathological implications from Italian nationwide survey study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021 Mar;3(3):e166–e168. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00007-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Starnoni M., Baccarani A., Pappalardo M., De Santis G. Management of personal protective equipment in plastic surgery in the era of coronavirus disease. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020 May;8(5):e2879. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baccarani A., Pappalardo M., Starnoni M., De Santis G. Plastic surgeons in the middle of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic storm in Italy. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020 May;8(5):e2889. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Santis G., Palladino T., Leti Acciaro A., Starnoni M. The Telematic solutions in plastic surgery during COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020 Jul 28;91(3) doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i3.10291. (ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leti Acciaro A., Montanari S., Venturelli M., Starnoni M., Adani R. Retrospective study in clinical governance and financing system impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in the hand surgery and microsurgery HUB center. Musculoskelet Surg. 2021 Feb 2 doi: 10.1007/s12306-021-00700-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giuggioli D., Manfredi A., Lumetti F., Colaci M., Ferri C. Scleroderma skin ulcers definition, classification and treatment strategies our experience and review of the literature. Autoimmun Rev. 2018 Feb;17(2):155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2017.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lázaro-Martínez J.L., Conde-Montero E., Alvarez-Vazquez J.C., Berenguer-Rodríguez J.J., Carlo A.G., Blasco-Gil S., et al. Preliminary experience of an expert panel using Triangle Wound Assessment for the evaluation of chronic wounds. J Wound Care. 2018 Nov 2;27(11):790–796. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2018.27.11.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giuggioli D., Manfredi A., Colaci M., Lumetti F., Ferri C. Scleroderma digital ulcers complicated by infection with fecal pathogens. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012 Feb;64(2):295–297. doi: 10.1002/acr.20673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giuggioli D., Manfredi A., Colaci M., Lumetti F., Ferri C. Osteomyelitis complicating scleroderma digital ulcers. Clin Rheumatol. 2013 May;32(5):623–627. doi: 10.1007/s10067-012-2161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khanna D., Furst D.E., Clements P.J., Allanore Y., Baron M., Czirjak L., et al. Standardization of the modified Rodnan skin score for use in clinical trials of systemic sclerosis. J Scleroderma Relat Disord. 2017 Apr;2(1):11–18. doi: 10.5301/jsrd.5000231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pope J. Measures of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma): health assessment questionnaire (HAQ) and scleroderma HAQ (SHAQ), physician- and patient-rated global assessments, symptom burden index (SBI), University of California, Los Angeles, scleroderma clinical trials consortium gastrointestinal scale (UCLA SCTC GIT) 2.0, baseline dyspnea index (BDI) and transition dyspnea index (TDI) (Mahler's Index), Cambridge Pulmonary Hypertension Outcome Review (CAMPHOR), and Raynaud's Condition Score (RCS) Arthritis Care & Research. 2011;63(S11):S98–S111. doi: 10.1002/acr.20598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ingegnoli F., Galbiati V., Boracchi P., Comi D., Gualtierotti R., Zeni S., et al. Reliability and validity of the Italian version of the hand functional disability scale in patients with systemic sclerosis. Clin Rheumatol. 2008 Jun;27(6):743–749. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0785-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mouthon L., Rannou F., Bérezné A., Pagnoux C., Arène J.-P., Foïs E., et al. Development and validation of a scale for mouth handicap in systemic sclerosis: the Mouth Handicap in Systemic Sclerosis scale. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 Dec;66(12):1651–1655. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.070532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Melzack R. The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain. 1987 Aug;30(2):191–197. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)91074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sebastiani M., Manfredi A., Colaci M., D’amico R., Malagoli V., Giuggioli D., et al. Capillaroscopic skin ulcer risk index: a new prognostic tool for digital skin ulcer development in systemic sclerosis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 May 15;61(5):688–694. doi: 10.1002/art.24394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Capillaroscopic Skin Ulcers Risk Index (CSURI) calculated with different videocapillaroscopy devices: how its predictive values change [Internet]. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. [cited 2021 Jun 20]. Available from: https://www.clinexprheumatol.org/abstract.asp?a=6419. [PubMed]

- 47.Sebastiani M., Manfredi A., Cassone G., Giuggioli D., Ghizzoni C., Ferri C. Measuring microangiopathy abnormalities in systemic sclerosis patients: the role of capillaroscopy-based scoring models. Am J Med Sci. 2014 Oct;348(4):331–336. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manfredi A., Sebastiani M., Campomori F., Pipitone N., Giuggioli D., Colaci M., et al. Nailfold Videocapillaroscopy Alterations in Dermatomyositis and Systemic Sclerosis: Toward Identification of a Specific Pattern. J Rheumatol. 2016 Aug;43(8):1575–1580. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.160122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sebastiani M., Manfredi A., Vukatana G., Moscatelli S., Riato L., Bocci M., et al. Predictive role of capillaroscopic skin ulcer risk index in systemic sclerosis: a multicentre validation study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 Jan;71(1):67–70. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sandqvist G., Eklund M. Hand Mobility in Scleroderma (HAMIS) test: the reliability of a novel hand function test. Arthritis Care Res. 2000 Dec;13(6):369–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Giuggioli D., Manfredi A., Vacchi C., Sebastiani M., Spinella A., Ferri C. Procedural pain management in the treatment of scleroderma digital ulcers. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015 Feb;33(1):5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Giuggioli D., Manfredi A., Colaci M., Ferri C. Oxycodone in the long-term treatment of chronic pain related to scleroderma skin ulcers. Pain Med. 2010 Oct;11(10):1500–1503. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Starnoni M., Pinelli M., De Santis G. Surgical Wound Infections in Plastic Surgery: Simplified, Practical, and Standardized Selection of High-risk Patients. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2019 Apr;7(4) doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Starnoni M., Pinelli M., Porzani S., Baccarani A., De Santis G. Standardization and Selection of Highrisk Patients for Surgical Wound Infections in Plastic Surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021 Mar;9(3) doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000003472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Giuggioli D., Lumetti F., Spinella A., Cocchiara E., Sighinolfi G., Citriniti G., et al. Use of Neem oil and Hypericum perforatum for treatment of calcinosis-related skin ulcers in systemic sclerosis. J Int Med Res. 2020 Apr;48(4) doi: 10.1177/0300060519882176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Giuggioli D., Sebastiani M., Cazzato M., Piaggesi A., Abatangelo G., Ferri C. Autologous skin grafting in the treatment of severe scleroderma cutaneous ulcers: a case report. Rheumatology. 2003 May 1;42(5):694–696. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Giuggioli D., Colaci M., Manfredi A., Mariano M., Ferri C. Platelet gel in the treatment of severe scleroderma skin ulcers. Rheumatol Int. 2012 Sep;32(9):2929–2932. doi: 10.1007/s00296-011-2038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pignatti M., Spinella A., Cocchiara E., Boscaini G., Lusetti I.L., Citriniti G., et al. Autologous Fat Grafting for the Oral and Digital Complications of Systemic Sclerosis: Results of a Prospective Study. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2020 Oct;44(5):1820–1832. doi: 10.1007/s00266-020-01848-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Giuggioli D., Spinella A., Cocchiara E., de Pinto M., Pinelli M., Parenti L., et al. Autologous fat grafting in the treatment of a scleroderma stump-skin ulcer: a case report. Case Reports Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2021 Feb 12;8(1):18–22. doi: 10.1080/23320885.2021.1881521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Del Papa N., Di Luca G., Andracco R., Zaccara E., Maglione W., Pignataro F., et al. Regional grafting of autologous adipose tissue is effective in inducing prompt healing of indolent digital ulcers in patients with systemic sclerosis: results of a monocentric randomized controlled study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21:7. doi: 10.1186/s13075-018-1792-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.De Santis G., Pinelli M., Benanti E., Baccarani A., Starnoni M. Lipofilling after Laser-Assisted Treatment for Facial Filler Complication: Volumetric and Regenerative Effect. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021 Mar 1;147(3):585–591. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000007611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carr Z.J., Klick J., McDowell B.J., Charchaflieh J.G., Karamchandani K. An Update on Systemic Sclerosis and its Perioperative Management. Curr Anesthesiol Rep. 2020 Aug 29:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s40140-020-00411-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ye F., Kong G., Huang J. Anesthetic management of a patient with localised scleroderma Springerplus. 2016;5(1):1507. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-3189-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shionoya Y., Kamiga H., Tsujimoto G., Nakamura E., Nakamura K., Sunada K. Anesthetic Management of a Patient With Systemic Sclerosis and Microstomia. Anesth Prog. 2020 Spring;67(1):28–34. doi: 10.2344/anpr-66-03-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kowal-Bielecka O., Fransen J., Avouac J., Becker M., Kulak A., Allanore Y., et al. Update of EULAR recommendations for the treatment of systemic sclerosis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2017 Aug 1;76(8):1327–1339. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cestelli V., Manfredi A., Sebastiani M., Praino E., Cannarile F., Giuggioli D., et al. Effect of treatment with iloprost with or without bosentan on nailfold videocapillaroscopic alterations in patients with systemic sclerosis. Mod Rheumatol. 2017 Jan;27(1):110–114. doi: 10.1080/14397595.2016.1192761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Negrini S., Magnani O., Matucci-Cerinic M., Carignola R., Data V., Montabone E., et al. Iloprost use and medical management of systemic sclerosis-related vasculopathy in Italian tertiary referral centers: results from the PROSIT study. Clin Exp Med. 2019 Aug;19(3):357–366. doi: 10.1007/s10238-019-00553-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Colaci M., Lumetti F., Giuggioli D., Guiducci S., Bellando-Randone S., Fiori G., et al. Long-term treatment of scleroderma-related digital ulcers with iloprost: a cohort study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017 Oct;35(Suppl 106):179–183. (4) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ingegnoli F., Schioppo T., Allanore Y., Caporali R., Colaci M., Distler O., et al. Practical suggestions on intravenous iloprost in Raynaud's phenomenon and digital ulcer secondary to systemic sclerosis: Systematic literature review and expert consensus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019 Feb;48(4):686–693. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bellando-Randone S., Bruni C., Lepri G., Fiori G., Bartoli F., Conforti M.L., et al. The safety of iloprost in systemic sclerosis in a real-life experience. Clin Rheumatol. 2018 May;37(5):1249–1255. doi: 10.1007/s10067-018-4043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Giuggioli D., Lumetti F., Colaci M., Fallahi P., Antonelli A., Ferri C. Rituximab in the treatment of patients with systemic sclerosis. Our experience and review of the literature. Autoimmun Rev. 2015, Nov;14(11):1072–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ferri C., Giuggioli D., Sebastiani M., Colaci M. Treatment of severe scleroderma skin ulcers with recombinant human erythropoietin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007 May;32(3):287–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2007.02363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Giuggioli D., Magistro R., Colaci M., Franciosi U., Caruso A., Ferri C. [The treatment of skin ulcers in systemic sclerosis: use of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) in 26 patients] Reumatismo. 2006 Mar;58(1):26–30. doi: 10.4081/reumatismo.2006.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pappalardo Marco, et al. Immunomodulation in vascularized composite allotransplantation: what is the role for adipose-derived stem cells? Ann. Plast. Surg. 2019;82(2):245–251. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Di Stefano Anna Barbara, Pappalardo Marco, et al. MicroRNAs in solid organ and vascularized composite allotransplantation: Potential biomarkers for diagnosis and therapeutic use. Transplant. Rev. (Orlando) 2020;34(4):100566. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2020.100566. Epub 2020 Jul 8. (* co-first authors) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cesari G., et al. Microfragmented adipose tissue is associated with improved ex vivo performance linked to HOXB7 and b-FGF expression. Stem Cell Res. Therapy. 2021;12(1) doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02540-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]