Abstract

Introduction:

The Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP) improves self-efficacy and health outcomes in people with chronic diseases. In the context of the EFFICHRONIC project, we evaluated the efficacy of CDSMP in relieving frailty, as assessed by the self-administered version of Multidimensional Prognostic Index (SELFY-MPI), identifying also potential predictors of better response over 6-month follow-up.

Methods:

The SELFY-MPI explores mobility, basal and instrumental activities of daily living (Barthel mobility, ADL, IADL), cognition (Test Your Memory-TYM Test), nutrition (Mini Nutritional Assessment-Short Form-MNA-SF), comorbidities, medications, and socio-economic conditions (social-familiar evaluation scale-SFES). Participants were stratified in three groups according to the 6-month change of SELFY-MPI: those who improved after CDSMP (Δ SELFY-MPI < 0), those who remained unchanged (Δ SELFY-MPI = 0), and those who worsened (Δ SELFY-MPI > 0). Multivariable logistic regression was modeled to identify predictors of SELFY-MPI improvement.

Results:

Among 270 participants (mean age = 61.45 years, range = 26–93 years; females = 78.1%) a benefit from CDSMP intervention, in terms of decrease in the SELFY-MPI score, was observed in 32.6% of subjects. SELFY-MPI improvement was found in participants with higher number of comorbidities (1–2 chronic diseases: adjusted odd ratio (aOR)=2.38, 95% confidence interval (CI) =1.01, 5.58; ⩾ 3 chronic diseases: aOR = 3.34, 95% CI = 1.25, 8.90 vs no chronic disease), poorer cognitive performance (TYM ⩽ 42: aOR = 2.41, 95% CI = 1.12, 5.19 vs TYM > 42) or higher risk of malnutrition (MNA-SF ⩽ 11: aOR = 6.11, 95% CI = 3.15, 11.83 vs MNA-SF > 11).

Conclusion:

These findings suggest that the CDSMP intervention contributes to decreasing the self-perceived severity of frailty (SELFY-MPI score) in more vulnerable participants with several chronic diseases and lower cognitive performance and nutritional status.

Keywords: chronic disease, cognitive deficit, frailty, malnutrition, multidimensional prognostic index, self-assessment

Introduction

The Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP) is an evidence-based program designed to improve the self-management of chronic conditions.1,2 The CDSMP was developed on the Bandura’s 3 Self-efficacy theory, and can be attended by an heterogenous population with several chronic health and mental conditions, but also their caregivers.4,5

Large amount of evidence supported the effectiveness of the CDSMP in improving physical and psychological well-being,6,7 health-related quality of life, 8 medication utilization, 9 and communication with health professionals. 8 Moreover, healthcare-related cost savings were demonstrated in several studies in terms of reduction in visits to general practitioner, admission to the emergency department and besides lower frequency and shorter duration of hospitalization.10,11

Although it has been clearly demonstrated that CDSMP led to better health outcomes, an important issue is identifying whether baseline participants’ characteristics are able to predict better clinical outcomes after attending this intervention. It has been demonstrated how lower self-efficacy and health-related quality of life, and younger age at baseline were correlated with more positive health outcomes after CDSMP. 12 Nevertheless, it seems that no studies focused on the impact of the CDSMP on the self-perceived frailty condition of such vulnerable people.

The EU-funded project EFFICHRONIC (Enhancing health systems sustainability by providing cost-efficiency data based interventions for chronic management in stratified population based on clinical and socio-economic determinants of health) tested the impact of the implementation of the CDSMP on the health systems sustainability in five European countries (France, Italy, Spain, The Netherlands, UK) in terms of the positive return of investment and cost-efficiency.13,14 In this framework it has been recently developed and validated a self-administered version of the Multidimensional Prognostic Index (SELFY-MPI). 15 This is derived from the Multidimensional Prognostic Index (MPI) a well-validated prognostic tool exploring the multidimensional impairment across multiple areas including physical, cognitive, biological, nutritional, and social domains. 16 The SELFY-MPI might be a useful stratification tool able to easily assess frailty risk condition without being influenced by age. 15

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the usefulness of the CDSMP in improving the SELFY-MPI score over 6-month follow-up and detecting potential predictors of a better response among community-dwelling subjects with chronic diseases and their caregivers.

Methods

Study design and population

The population level recruitment was part of the project “738127/EFFICHRONIC,” a multicentre non-controlled prospective study, which received funding from the European Union’s Health Program (2014–2020). The EFFICHRONIC project was developed and implemented in five European countries (France, Italy, Spain, The Netherlands, United Kingdom) between June 2018 and February 2020, but the present study collected the population recruited in Montpellier (France) and Genoa (Italy) specifically.

The inclusion criteria were: (I) age 18 years or over; (II) presence of at least one chronic condition (defined according to the International Classification of Primary Care—ICPC-2) with at least > 6 months of evolution; (III) informal caregivers who live socially isolated; (IV) absence of acute clinical condition; (V) ability to provide informed consent; (VI) availability to attend a six-weeks course. Subjects were excluded whether: (I) could not commit to a 6-month follow-up regardless of the reason; (II) lived a period of crisis (domestic violence, refugees without a stable environment, eviction, etc.), (III) were homeless or roofless, (IV) were affected by severe mental health problems according to DSM V distorting perception of reality and/or prejudicing the ability to function in a group, (V) had cognitive decline (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease), (VI) had active addictive disorders (drugs, alcohol), (VII) did not have adequate knowledge of the language of the country of residence, and (VIII) were prisoners or subjects who were involuntary incarcerated.

In this post hoc, per-protocol analysis, out of 592 subjects screened in Montpellier and Genoa centers, we included 270 participants (45.6%) who had attended more than half of CDMSP sessions (at least four of six) and had completed the SELFY-MPI at baseline as well as at 6-month follow-up (Supplementary Figure 1).

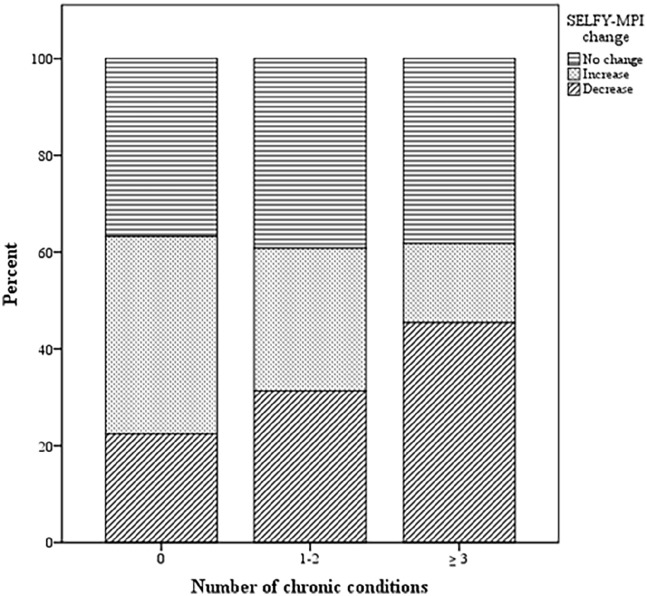

Figure 1.

Proportion of subjects experiencing no change, increase or decrease of SELFY-MPI by number of chronic conditions.

All participants enrolled read and signed the informed consent form and all their records and personal information were made anonymous. This longitudinal cohort study was conducted according to the World Medical Association’s 2008 Declaration of Helsinki and according to the ethical regulations of each study site. The trial is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT03840447).

Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP)

The CDSMP is designed along the self-efficacy theory and allows sharing of skills that are common to a wide variety of chronic conditions such as coping skills, symptoms control, problem solving, confidence building, and decision making. 3 The CDSMP intervention consisted of 6 weekly workshops of 2.5 hours each, led by two leaders (an healthcare professional and a lay-person together) who adhered to a detailed manual. 17 All workshop leaders were trained by Standford-certified CDSMP master trainer and each edition of the program was not modified from the standard CDSMP protocol both in France and in Italy. The intervention was structured as face-to-face small-group meetings attended by about 15 participants. Discussed topics included information on exercise, healthy nutrition, cognitive symptom-management techniques, fatigue-management, dealing with fear, anger, and depression, learn how to control pain and discomfort, communication with others including health professionals, use of medications, action planning, problem solving, and decision making.

Each CDSMP delivery site recruited participants for their workshops in several ways including flyers, brochures, snowball sampling and referrals from health and social local organizations.

To ensure a better adherence to CDSMP intervention, also after center-based visits and during all the 6-month follow-up, each participants received a handout with the workshop topics, homework assignments, and a consultation book.

Self-administered Multidimensional Prognostic Index (SELFY-MPI)

The self-administered Multidimensional Prognostic Index (SELFY-MPI) is a validate, composite tool, stemming from the standard MPI, and thus able to detect frailty condition based on the principles of Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA). 18 It is structured on information derived by eight domains each one assessed through the following self-administered scales 15 :

(a) Functional status evaluated by the Barthel Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scale, 19 in its self-assessed version. 20 This scale measures the level of dependence/independence in six daily personal care activities: feeding, bathing, personal hygiene, dressing, fecal and urinary continence and toilet use.

(b) Mobility assessed through the Barthel mobility sub-scale, 19 which assess the following three abilities: going up and down the stairs, walking and getting in and out of bed/chair. This scale may be self-administered. 20

(c) Independence in the instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) 21 measured through the self-administered version of Lawton’s IADL scale that investigates the independence in the following eight activities: telephone use, grocery shopping, meal preparation, housekeeping, laundry, travel, medication and handling finances. 22

(d) Cognitive status assessed through the self-administered cognitive screening test Your Memory (TYM) that is a 10-task performance test exploring several cognitive domains such as orientation, ability to copy a sentence, semantic knowledge, calculation, verbal fluency, similarities, naming, visuo-spatial abilities and recall of a previously copied sentence. 23 Its score ranges between 0 and 50, with higher scores denoting a better cognitive performance.

(e) Nutritional status evaluated through the self-administered version of the Mini Nutritional Assessment Short-Form (MNA-SF), that contains information regarding the weight loss, the decline in food intake, mobility, recent psychological stress, neuropsychological problems and anthropometric measure (body mass index). 24

(f) Number of drugs taken regularly cross-checked with the comorbidities.

(g) Comorbidity assessed by investigating the number of pathologies, among the first 13 categories of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) 25 for which a drug therapy is prescribed and assumed regularly.

(h) Social and economic situation evaluated through an adapted version of Gijón social-familial evaluation scale (SFES). 26 This scale explores socio-economic variables such as: participant’s household composition, the net monthly household income, housing situation, participant’s social relationships and social support. The maximum score of the SFES scale is 25 points; scores > 15 indicate social problems and scores between 10 and 14 a potential social risk.

For each domain, a tripartite hierarchy was adopted based on conventional cut-off points 15 : a score of 0 indicates no problems, 0.5 minor problems and 1.0 major problems (Table 1). The sum of these eight domains must be divided by 8 in order to obtain the SELFY-MPI score which ranges from 0 (no multidimensional impairment) to 1 (maximum multidimensional impairment).

Table 1.

Domains of the Self-Administered-MPI and its calculation.

| SELFY-MPI | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Level of risk | |||

| Risk low = 0 | Risk moderate = 0.5 | Risk high = 1 | |

| 1. Barthel ADL | 0–14 | 15–49 | 50–60 |

| 2. Barthel mobility | 0–14 | 15–29 | 30–40 |

| 3. IADL | 8–6 | 5–4 | 3–0 |

| 4. TYM | 50–43 | 42–24 | 23–0 |

| 5. MNA-SF | 14–12 | 11–8 | 7–0 |

| 6. Self-reported CIRS | 0 | 1–2 | 3–13 |

| 7. Number of drugs | 0–3 | 4–6 | ⩾7 |

| 8. SFES | 5–9 | 10–14 | 15–25 |

| Sum the numbers assigned to each domain and divide by 8 | Total Score SELFY-MPI | ||

ADL, activities of daily living; CIRS, Cumulative Illness Rating Scale; IADL, Instrumental Activities of daily Living; MNA-SF, Mini Nutritional Assessment Short Form; SELFY-MPI, Self-administered Multidimensional Prognostic Index; SFES, Social-Familial Evaluation Scale; TYM, Test Your Memory.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and as absolute and relative frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables. Differences between SELFY-MPI at 6-month and SELFY-MPI at baseline (ΔSELFY-MPI) were calculated for each patient. Thus, we stratified participants in three groups according the ΔSELFY-MPI: those who improved (ΔSELFY-MPI < 0), those who remained unchanged (ΔSELFY-MPI = 0), and those who worsened (ΔSELFY-MPI > 0). To test difference between subjects with different number of comorbidities (i.e. 0 -recruited among accompanying caregivers of included patients with chronic diseases-, 1–2 chronic diseases, or 3 and more) or with different ΔSELFY-MPI, we used one-way ANOVA for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. Bonferroni correction was adopted to account for multiple comparisons. To visually compare changes in each different SELFY-MPI domain, we calculated the z-scores of each scale change over time. Multivariable logistic regression was modeled to identify potential predictors of SELFY-MPI improvement among: age > 65 years, gender, number of comorbidities (i.e. 0, 1–2, ⩾ 3), and dichotomized variables, based on well-established cut-off, for impaired mobility (Barthel mobility > 0), poor social condition (SFES ⩾ 10), cognitive disorders (TYM ⩽ 42) and higher risk of malnutrition (MNA-SF ⩽ 11). We further adjusted the results for clinical site and full attendance to CDSMP and SELFY-MPI at baseline. All analyses were conducted using SPSS software version 26.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York). Two-tailed probabilities were reported and a p-value of 0.05 was used to define nominal statistical significance.

Results

Overall, 270 subjects from Italian and French cohort (mean age 61.45 ± 13.55 years, range 26–93 years; females: 78.1%) attended more than half of the CDSMP (60.7% followed all the sessions) and completed the SELFY-MPI both at baseline and at 6-month follow-up. We included 49 caregivers without chronic diseases, 166 subjects with one or two chronic diseases and 55 with three or more chronic diseases. Mean SELFY-MPI score at baseline was 0.17 (SD: 0.12).

Participants who did not perform SELFY-MPI assessment at 6-month follow-up, due to COVID-19 restrictions, had similar age (mean age: 61.2 years old) and gender (female: 75.2%) distribution compared to subjects included in the analysis, but were more compromised at SELFY-MPI assessment performed at baseline (0.24).

Table 2 showed baseline characteristics of participants based on number of comorbidities. Subjects with chronic diseases were significantly older than healthy participants and, as we expected, reported a progressive increase of total medications and of SELFY-MPI score as the number of disease increases. Those subjects with three or more chronic conditions had also significantly higher body mass index (BMI) and lower rate of independency in IADL compared to healthy participants.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the EFFICHRONIC study population according to the number of reported chronic conditions.

| No chronic disease (n = 49) | 1–2 chronic diseases (n = 166) | ⩾ 3 chronic diseases (n = 55) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 55.02 (14.36) | 61.98 (12.90)* | 65.45 (13.00)* | <0.001 |

| Age > 65y, n (%) | 11 (22.9) | 68 (41.0) | 25 (45.5) | 0.040 |

| Female, n (%) | 35 (71.4) | 134 (81.2) | 42 (76.4) | 0.314 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 24.11 (4.98) | 25.84 (4.83) | 26.60 (4.67)* | 0.026 |

| Independency in ADL, n (%) | 45 (91.8) | 136 (81.9) | 42 (76.4) | 0.108 |

| Independency in mobility, n (%) | 41 (83.7) | 141 (84.9) | 44 (80.0) | 0.691 |

| Independency in IADL, n (%) | 38 (77.6) | 127 (76.5) | 32 (58.2)* † | 0.022 |

| TYM, mean (SD) | 45.59 (6.21) | 45.69 (3.91) | 45.84 (3.33) | 0.957 |

| MNA-SF, mean (SD) | 11.06 (2.33) | 11.37 (2.42) | 10.53 (2.45) | 0.081 |

| Medications, median (IQR) | 0 (0) | 2 (2)* | 5 (3)* † | <0.001 |

| SFES, mean (SD) | 8.75 (3.24) | 8.18 (2.84) | 8.82 (2.68) | 0.243 |

| SELFY-MPI mean (SD) | 0.09 (0.11) | 0.15 (0.09)* | 0.28 (0.13)* † | <0.001 |

ADL, activities of daily living; BMI, body mass index; EFFICHRONIC, Enhancing health systems sustainability by providing cost-efficiency data based interventions for chronic management in stratified population based on clinical and socio-economic determinants of health; IADL, Instrumental Activities of daily Living; IQR, interquartile range; MNA-SF, Mini Nutritional Assessment Short Form; SD, standard deviation; SELFY-MPI, Self-administered Multidimensional Prognostic Index; SFES, Social-Familial Evaluation Scale; TYM, Test Your Memory.

<0.05 vs “no chronic disease” group after Bonferroni correction.

<0.05 vs “1–2 chronic diseases” group after Bonferroni correction.

At 6-month follow-up, mean SELFY-MPI did not significantly change compared to baseline (0.17, SD: 0.13). However, stratifying subjects based on ΔSELFY-MPI, we found a benefit from CDSMP intervention, in terms of decrease in the SELFY-MPI score at 6 months, in the 32.6% of participants, while 28.9% worsened and 38.5% remained stable. Comparing subjects who experienced an improvement of SELFY-MPI with those who worsened or remained unchanged, we found that the formers were on average more cognitively impaired, malnourished and with more medications at baseline (Table 3). Subjects with higher number of comorbidities reported higher proportion of improvement in SELFY-MPI at 6 months (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Characteristics of the EFFICHRONIC study population according to change in SELFY-MPI at 6 months.

| No change of SELFY-MPI | Decrease of SELFY-MPI | Increase of SELFY-MPI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 104 (38.5) | 88 (32.6) | 78 (28.9) | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 62.72 (14.22) | 60.02 (11.03) | 61.33 (15.12) | 0.391 |

| Age > 65y, n (%) | 46 (44.2) | 27 (31.0) | 31 (39.8) | 0.171 |

| Female, n (%) | 76 (73.1) | 71 (80.7) | 64 (82.0) | 0.240 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 25.64 (3.91) | 25.91 (4.90) | 25.47 (5.93) | 0.838 |

| Independency in ADL, n (%) | 91 (87.5) | 70 (79.5) | 62 (79.5) | 0.242 |

| Independency in mobility, n (%) | 95 (91.3) | 71 (80.7) | 60 (76.9) † | 0.022 |

| Independency in IADL, n (%) | 80 (76.9) | 60 (68.2) | 50 (73.1) | 0.397 |

| TYM, mean (SD) | 46.58 (3.53) | 44.58 (5.35) † | 45.79 (3.64) | 0.005 |

| MNA-SF, mean (SD) | 11.85 (2.30) | 10.18 (2.18)* † | 11.28 (2.53) | <0.001 |

| CIRS, mean (SD) | 1.63 (1.41) | 1.99 (1.56) | 1.45 (1.48) | 0.058 |

| Medications, median (IQR) | 2 (2) | 3 (4)* † | 2 (2.3) | 0.009 |

| SFES, mean (SD) | 7.72 (2.43) | 8.76 (2.77) | 8.95 (3.40) † | 0.007 |

| SELFY-MPI, mean (SD) | 0.13 (0.10) | 0.22 (0.10)* † | 0.16 (0.14) | <0.001 |

| Sessions attended, mean (SD) | 5.54 (0.67) | 5.58 (0.67) | 5.32 (0.75) | 0.038 |

ADL, activities of daily living; BMI, body mass index; CIRS, Cumulative Illness Rating Scale; EFFICHRONIC, Enhancing health systems sustainability by providing cost-efficiency data based interventions for chronic management in stratified population based on clinical and socio-economic determinants of health; IADL, Instrumental Activities of daily Living; IQR, interquartile range; MNA-SF, Mini Nutritional Assessment Short Form; SD, standard deviation; SELFY-MPI, Self-administered Multidimensional Prognostic Index; SFES, Social-Familial Evaluation Scale; TYM, Test Your Memory.

<0.05 vs “Increase of SELFY_MPI” group after Bonferroni correction.

<0.05 vs “No change of SELFY_MPI” group after Bonferroni correction.

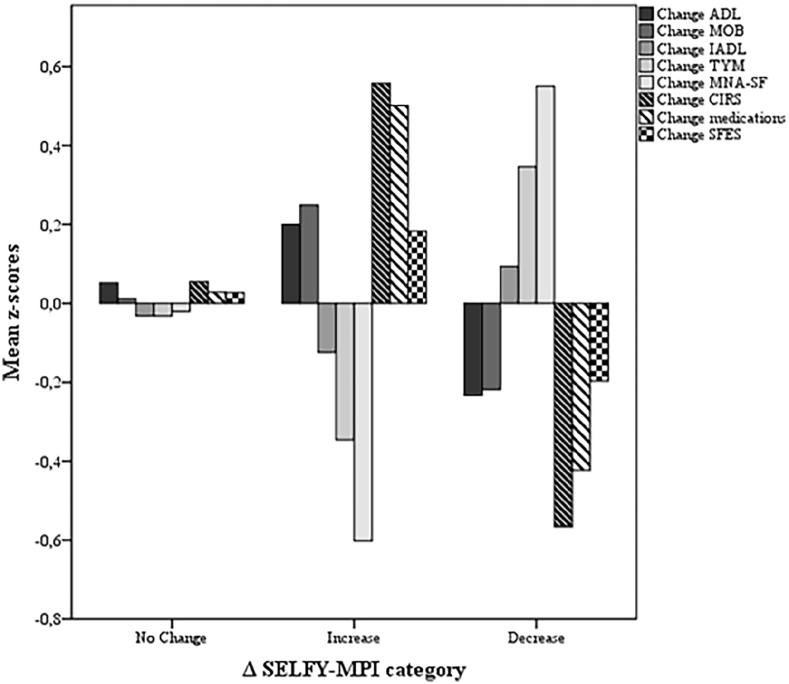

Independently of potential confounders including age, gender, CDSMP attendance and SELFY-MPI score at baseline, higher number of comorbidities (1–2 chronic diseases: adjusted odd ratio (aOR)= 2.38, 95% confidence interval (CI)= 1.01, 5.58; ⩾ 3 chronic diseases: aOR = 3.34, 95% CI = 1.25, 8.90 vs no chronic disease), lower cognitive performance (TYM ⩽ 42: aOR = 2.41, 95% CI = 1.12, 5.19 vs TYM > 42) and poorer nutritional status (MNA-SF ⩽ 11: aOR = 6.11, 95% CI = 3.15, 11.83 vs MNA-SF > 11) predicted an improvement of SELFY-MPI after CDSMP (Table 4). Among subjects who experienced reduction of SELFY-MPI, the greatest benefits were observed in terms of reduction of number of comorbidities (z-score: -0.55 SD, p < 0.001) and medications (z-score: -0.48 SD, p < 0.001) and improvement of nutritional (ΔMNA-SF z-score: 0.56 SD, p < 0.001) and cognitive (ΔTYM z-score: 0.34 SD, p < 0.001) domains (Figure 2).

Table 4.

Selected baseline characteristics as predictors of the improvement in SELFY-MPI score at 6 months.

| Independent variable | Reduction of SELFY-MPI | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR a | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Age > 65 years | 0.86 | 0.44–1.67 | 0.657 |

| Female | 1.10 | 0.54–2.26 | 0.792 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| 0 | REF | ||

| 1–2 | 2.38 | 1.01–5.58 | 0.047 |

| ⩾ 3 | 3.34 | 1.25–8.90 | 0.016 |

| Impaired mobility (Barthel mobility > 0) | 0.78 | 0.32–1.88 | 0.577 |

| SFES ⩾ 10 | 1.51 | 0.69–3.31 | 0.307 |

| TYM ⩽ 42 | 2.41 | 1.12–5.19 | 0.024 |

| MNA-SF ⩽ 11 | 6.11 | 3.15–11.83 | < 0.001 |

CI, confidence interval; MNA-SF, Mini Nutritional Assessment Short Form; OR, odd ratio; SELFY-MPI, Self-administered Multidimensional Prognostic Index; SFES, Social-Familial Evaluation Scale; TYM, Test Your Memory.

corrected also for clinical site, full attendance of Chronic Disease Self-Management Program and SELFY-MPI at baseline.

Figure 2.

Change of SELFY-MPI domains (z-scores) according to ΔSELFY-MPI categories.

Discussion

In this cohort of community-dwelling subjects with chronic diseases and their caregivers, we found that, after 6-month CDSMP, the self-perceived multidimensional impairment was reduced compared to the baseline measurement, as assessed by SELFY-MPI, in around one-third of participants. Higher number of comorbidities as well as higher level of cognitive impairment and malnutrition at baseline were independent predictors of greater benefit from CDSMP in terms of SELFY-MPI reduction.

Most consistent outcomes in randomized controlled trials testing CDSMP are improvement in aerobic exercise, management of cognitive symptoms, psychological health, communication with physicians and reduced hospitalizations. 6 To our knowledge, this is the first study assessing the efficacy of CDSMP in reducing self-reported frailty condition based on change of a well-validated tool, the SELFY-MPI that measures impairment across multiple domains (i.e. functional, mobility, cognitive, nutritional, comorbidities, drugs and social conditions). The SELFY-MPI was derived from traditional MPI, performed by health professionals. 16 The MPI proved excellent accuracy in predicting several negative outcomes among community-dwelling older adults with chronic diseases and was also recognized as a useful tool able to track changes in health status and to measure frailty condition through a CGA-based multidimensional approach. 18 Given the strong agreement with the standard MPI, 15 the SELFY-MPI score could be similarly a good indicator of frailty condition.

Here we found that presence of three or more chronic conditions, lower cognitive performance and poorer nutritional status, at baseline, significantly predicted a successful outcome after CDSMP. These findings suggest that people with higher illness burden may benefit more from CDSMP. Indeed, previous evidence from a randomized controlled trial carried out on 629 subjects with chronic diseases, showed that poorer health status and lower confidence in the management of chronic disease were strong predictors of greater benefit on health-related quality of life in patients undergoing CDSMP. 12 Moreover, subjects with higher number of comorbidities (i.e. two or more chronic diseases plus depression) reported higher effectiveness of CDSMP on vitality and quality of life. 27

Among subjects who reported a reduction of SELFY-MPI after CDSMP, greater benefit in self-perceived multidimensional assessment was observed in terms of reduction of comorbidities and medications, and improvement of cognitive and nutritional status. It is well established that multimorbidity is related to poor cognitive function and accelerated cognitive decline.28–30 Previous studies demonstrated that CDSMP was able to improve management of cognitive symptoms. 6 Also malnutrition is frequently associated with chronic diseases, probably due to a pro-inflammatory state, typical of chronic conditions that determines anorexia, malabsorption and alteration of metabolism. 31 Some report highlighted that lack of nutritional advices represents a serious complain among multimorbid subjects, 32 thus CDSMP might help to improve adherence to healthy diet lifestyle. Self-perceived reduction of burden of diseases and consequent deprescription could be also important goals of CDMSP and further efforts should be taken to broaden the spectrum of these benefits.

These findings are in our opinion of clinical importance since the availability of a sensitive and reliable global health status indicator, as the SELFY-MPI, would be useful for the management of patients with chronic diseases. In particular, in the framework of a CDSMP, the SELFY-MPI might help to reinforce aspects of the intervention mainly connected to the health domains with the highest degree of impairment (e.g. cognition, malnutrition).

This study has some limitations. First the absence of comparison group did not allow to compare the CDSMP to the standard of care. Second, the enrolled sample was relatively small, therefore we were not able to sub-divide numbers of physical conditions into more levels and explore the role of clusters of chronic diseases (e.g. diabetes and hypertension, diabetes and cancer). Third, we recruited a population of well-functioning community-dwelling subjects, thus further studies are warranted to confirm these results among more frail subjects from different kind of settings. Fourth, the attrition rate was high because of lockdown measures related to COVID-19 pandemic occurring during follow-up. Finally, given the post hoc nature of the analysis, the usefulness of SELFY-MPI in the identification of subjects who best benefit from CDSMP need to be tested in ad hoc-designed studies.

Conclusion

Our findings support the hypothesis that the CDSMP may contribute to the reduction of the self-perceived severity of frailty condition, based on SELFY-MPI score, in particular among more vulnerable subjects with more chronic diseases, lower cognitive performance and poorer nutritional status. Present findings should further encourage policy makers and stakeholders to promote CDSMP for reducing the healthcare burden of chronic diseases.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-doc-1-taj-10.1177_20406223211056722 for Impact of the chronic disease self-management program (CDSMP) on self-perceived frailty condition: the EU-EFFICHRONIC project by Sabrina Zora, Carlo Custodero, Yves-Marie Pers, Verushka Valsecchi, Alberto Cella, Alberto Ferri, Marta M. Pisano-González, Delia Peñacoba Maestre, Raquel Vazquez Alvarez, Hein Raat, Graham Baker and Alberto Pilotto in Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease

Supplemental material, sj-doc-2-taj-10.1177_20406223211056722 for Impact of the chronic disease self-management program (CDSMP) on self-perceived frailty condition: the EU-EFFICHRONIC project by Sabrina Zora, Carlo Custodero, Yves-Marie Pers, Verushka Valsecchi, Alberto Cella, Alberto Ferri, Marta M. Pisano-González, Delia Peñacoba Maestre, Raquel Vazquez Alvarez, Hein Raat, Graham Baker and Alberto Pilotto in Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease

Footnotes

Author contributions: S.Z.: data curation, project administration, and writing—original draft preparation; C.C.: methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation; YMP: investigation, writing—review and editing; V.V.: investigation, writing—review and editing; A.C.: investigation, writing—review and editing; A.F.: investigation, writing—review and editing; M.M.P.-G.: investigation, writing—review and editing; D.P.M.: investigation, writing—review and editing; R.V.A.: investigation, writing—review and editing; H.R.: investigation, writing—review and editing; G.B.: investigation, writing—review and editing; A.P.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, and writing—review and editing. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This publication is part of the project/joint action “738127/EFFICHRONIC,” which has received funding from the European Union’s Health Program (2014–2020).

Ethical approval: In Occitanie, France, the Ethics Committee of the South-west and Oversees I in Toulouse (Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud-Ouest et Outre-Mer I) approved this study on 5 November 2018 (study number 9788); in Genoa, Italy, the Ethical Committee of the Liguria Region, approved the present study on 27 March 2018 (study number 152-2018).

ORCID iD: Sabrina Zora  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9801-0626

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9801-0626

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Sabrina Zora, Geriatrics Unit, Department of Geriatric Care, Orthogeriatrics and Rehabilitation, EO Galliera Hospital, Genova, Italy.

Carlo Custodero, Department of Interdisciplinary Medicine, Clinica Medica e Geriatria “Cesare Frugoni,” University of Bari Aldo Moro, Bari, Italy.

Yves-Marie Pers, IRMB, University of Montpellier, INSERM, CHU Montpellier, Montpellier, France.

Verushka Valsecchi, IRMB, University of Montpellier, INSERM, CHU Montpellier, Montpellier, France.

Alberto Cella, Geriatrics Unit, Department of Geriatric Care, Orthogeriatrics and Rehabilitation, EO Galliera Hospital, Genova, Italy.

Alberto Ferri, Geriatrics Unit, Department of Geriatric Care, Orthogeriatrics and Rehabilitation, EO Galliera Hospital, Genova, Italy.

Marta M. Pisano-González, SESPA, Health Service of the Principality of Asturias, Research Group “Community Health and Active Aging” of the Research Institute of Asturias (IPSA), Oviedo, Spain

Delia Peñacoba Maestre, SESPA, Health Service of the Principality of Asturias, Research Group “Community Health and Active Aging” of the Research Institute of Asturias (IPSA), Oviedo, Spain.

Raquel Vazquez Alvarez, SESPA, Health Service of the Principality of Asturias, Research Group “Community Health and Active Aging” of the Research Institute of Asturias (IPSA), Oviedo, Spain.

Hein Raat, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Graham Baker, QISMET, Portsmouth, UK.

Alberto Pilotto, Director Geriatrics Unit and Department Geriatric Care, Orthogeriatrics and Rehabilitation, EO Galliera Hospital, Via Mura delle Cappuccine 16, 35121 Genova, Italy.

References

- 1. Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Ritter PL, et al. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Eff Clin Pract 2001; 4: 256–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Elzen H, Slaets JP, Snijders TA, et al. Evaluation of the chronic disease self-management program (CDSMP) among chronically ill older people in the Netherlands. Soc Sci Med 2007; 64: 1832–1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 1977; 84: 191–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ritter PL, Lee J, Lorig K. Moderators of chronic disease self-management programs: who benefits? Chronic Illn 2011; 7: 162–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shi J, McCallion P, Ferretti LA. Understanding differences between caregivers and non-caregivers in completer rates of Chronic Disease Self-Management Program. Public Health 2017; 147: 128–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brady TJ, Murphy L, O’Colmain BJ, et al. A meta-analysis of health status, health behaviors, and health care utilization outcomes of the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program. Prev Chronic Dis 2013; 10: 120112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ory MG, Ahn S, Jiang L, et al. National study of chronic disease self-management: six-month outcome findings. J Aging Health 2013; 25: 1258–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hevey D, Wilson O’Raghallaigh J, O’Doherty V, et al. Pre-post effectiveness evaluation of Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP) participation on health, well-being and health service utilization. Chronic Illn 2020; 16: 146–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee S, Jiang L, Dowdy D, et al. Effects of the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program on medication adherence among older adults. Transl Behav Med 2019; 9: 380–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lorig KR, Ritter P, Stewart AL, et al. Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Med Care 2001; 39: 1217–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Stewart AL, et al. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: a randomized trial. Med Care 1999; 37: 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reeves D, Kennedy A, Fullwood C, et al. Predicting who will benefit from an Expert Patients Programme self-management course. Br J Gen Pract 2008; 58: 198–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boone ALD, Pisano-Gonzalez MM, Valsecchi V, et al. EFFICHRONIC study protocol: a non-controlled, multicentre European prospective study to measure the efficiency of a chronic disease self-management programme in socioeconomically vulnerable populations. BMJ Open 2019; 9: e032073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tan SS, Pisano MM, Boone AL, et al. Evaluation design of EFFICHRONIC: the Chronic Disease Self-Management Programme (CDSMP) intervention for citizens with a low socioeconomic position. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 16: 1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pilotto A, Veronese N, Quispe Guerrero KL, et al. Development and validation of a self-administered multidimensional prognostic index to predict negative health outcomes in community-dwelling persons. Rejuvenation Res 2019; 22: 299–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pilotto A, Ferrucci L, Franceschi M, et al. Development and validation of a multidimensional prognostic index for one-year mortality from comprehensive geriatric assessment in hospitalized older patients. Rejuvenation Res 2008; 11: 151–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lorig K, Gonzalez V, Laurent D. The chronic disease self-management workshop leader’s manual. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford Patient Education Research Center, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pilotto A, Custodero C, Maggi S, et al. A multidimensional approach to frailty in older people. Ageing Res Rev 2020; 60: 101047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J 1965; 14: 61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Katz PP. Measures of adult general functional status: the Barthel Index, Katz Index of Activities of Daily Living, Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), MACTAR Patient Preference Disability Questionnaire, and Modified Health Assessment Questionnaire (MHAQ). Arthritis Care Res 2003; 49: S15–S27. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969; 9: 179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goeppinger J, Doyle M, Murdock B, et al. Self-administered function measures: the impossible dream? Arthritis Rheum 1985; 28(Suppl.): 145. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brown J, Pengas G, Dawson K, et al. Self administered cognitive screening test (TYM) for detection of Alzheimer’s disease: cross sectional study. BMJ 2009; 338: b2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Donini LM, Marrocco W, Marocco C, et al. Validity of the Self- Mini Nutritional Assessment (Self- MNA) for the evaluation of nutritional risk. A cross- sectional study conducted in general practice. J Nutr Health Aging 2018; 22: 44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Linn BS, Linn MW, Gurel L. Cumulative illness rating scale. J Am Geriatr Soc 1968; 16: 622–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. García González JV, Díaz Palacios E, Salamea García A, et al. [An evaluation of the feasibility and validity of a scale of social assessment of the elderly]. Aten Primaria 1999; 23: 434–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harrison M, Reeves D, Harkness E, et al. A secondary analysis of the moderating effects of depression and multimorbidity on the effectiveness of a chronic disease self-management programme. Patient Educ Couns 2012; 87: 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vassilaki M, Aakre JA, Cha RH, et al. Multimorbidity and risk of mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63: 1783–1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Loprinzi PD. Multimorbidity, cognitive function, and physical activity. Age (Dordr) 2016; 38: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wei MY, Levine DA, Zahodne LB, et al. Multimorbidity and cognitive decline over 14 years in older Americans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2020; 75: 1206–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Norman K, Pichard C, Lochs H, et al. Prognostic impact of disease-related malnutrition. Clin Nutr 2008; 27: 5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hakami R, Gillis DE, Poureslami I, et al. Patient and professional perspectives on nutrition in chronic respiratory disease self-management: reflections on nutrition and food literacies. Health Lit Res Pract 2018; 2: e166–e174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-doc-1-taj-10.1177_20406223211056722 for Impact of the chronic disease self-management program (CDSMP) on self-perceived frailty condition: the EU-EFFICHRONIC project by Sabrina Zora, Carlo Custodero, Yves-Marie Pers, Verushka Valsecchi, Alberto Cella, Alberto Ferri, Marta M. Pisano-González, Delia Peñacoba Maestre, Raquel Vazquez Alvarez, Hein Raat, Graham Baker and Alberto Pilotto in Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease

Supplemental material, sj-doc-2-taj-10.1177_20406223211056722 for Impact of the chronic disease self-management program (CDSMP) on self-perceived frailty condition: the EU-EFFICHRONIC project by Sabrina Zora, Carlo Custodero, Yves-Marie Pers, Verushka Valsecchi, Alberto Cella, Alberto Ferri, Marta M. Pisano-González, Delia Peñacoba Maestre, Raquel Vazquez Alvarez, Hein Raat, Graham Baker and Alberto Pilotto in Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease