Abstract

Provider-patient communication (PPC) skills are key in promoting patient satisfaction. Our study examined the relationship between clinician PPC skills and patient satisfaction with care among virally unsuppressed adult HIV patients in Busia County, Kenya. This cross-sectional study was conducted among 360 HIV patients on first line antiretroviral regimen and having a recent viral load ≥400 copies HIV RNA/ml. We conducted logistic regression analysis. The mean age of participants was 48.2 years [standard deviation (SD): 12.05]. Overall, the mean score on clinician PPC skills was 33.3 (SD: 9.0). A high proportion (85%) of participants reported satisfaction with the HIV care services. After adjusting for covariates, the odds of being satisfied with care increased by 19% (adjusted odds ratio: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.11-1.30) for every one unit increase in the clinician PPC skills score. Promoting good PPC skills may be key to improving patient satisfaction with HIV care.

Keywords: Patient satisfaction, provider-patient communication skills, HIV care, unsuppressed patients

Introduction

How HIV care is delivered in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) plays a critical role in patient adherence to and retention in care. Health system factors such as poor staff attitudes, congested clinics, long waiting times, discrimination and stigma, and distance to health facilities have been reported to affect adherence and retention of patients in care.1–3 Low capital and human resources, high demand for HIV services and a paternalistic approach to care have contributed to system level barriers in the region.4,5 In light of these challenges, there is need to improve the quality of HIV care services in order to enhance patient adherence and retention in care.

Patients who are the main beneficiary of HIV care systems 6 have their own expectations of health services. 7 This influences their level of satisfaction with the services they receive. 8 Patient satisfaction is a measure of how patients experience and perceive the quality of care received.6,8,9 There is evidence that patients who are satisfied with care are more likely to adhere to the treatment guidelines and hence be retained.10–12 Given the benefits achieved when patients are satisfied with care, health systems will greatly benefit from continued assessment of this construct.6,9 Feedback from these assessments may be used to inform the delivery of HIV care that ultimately promotes patient retention.

While there are a number of system-level factors that have been reported to be associated with patient satisfaction with care, including the physical status of the facility, availability of medication and time spent at the facility,11,13–19 patient-provider relationship dynamics may be the most critical to understanding patient satisfaction. Provider-patient communication (PPC) plays a critical role in facilitating better provider-patient relationship dynamics, empowers patients with knowledge about their health and promotes partnership between patients and providers in decision-making.20,21 Evidence from high income countries suggest that patients who perceive their clinician as having good communication skills also report satisfaction with care.11,13,15,17–19,22 This relationship has not yet been fully characterized in resource-limited settings with high HIV burden.11,13 We therefore examined the relationship between PPC skills and satisfaction with HIV care among virally unsuppressed adult HIV patients in Busia county, Kenya.

Methods

Study Site

The study was conducted in two rural health facilities offering HIV care in Busia County, Kenya. The two HIV health facilities, Khunyangu health facility and Port-Victoria health facility, are affiliated with the Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH) program. 23 These facilities were comparable in terms of the clinic capacity with a provider-patient ratio of 1:210 per month. In addition, they each had 5 clinic officers (equivalent to physician assistants in the US) providing day to day clinical care to patients living with HIV.

Study Design

We conducted a cross-sectional study as part of the baseline assessment of a pilot randomized control trial that aimed to promote patient engagement through an enhanced patient care intervention. The baseline assessments were done between August-December 2019. A detailed description of the intervention is provided elsewhere. 24 We obtained approval from Institutional Research and Ethics Committee (approval #0003297) at Moi University in Kenya. All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment in this study.

Study Population and Sample

We targeted adult patients living with HIV who were receiving HIV care at either of the two health facilities. Patients were considered eligible for the study if they were on a first line ART regimen and had a first elevated (≥400 copies HIV RNA/ml) viral load (VL) within three months prior to the study rollout. A sample of 360 patients with unsuppressed viral loads was the target sample size for the pilot randomized control trial.

Data Collection Instruments

We developed a structured interviewer-administered survey that incorporated adapted validated measures of provider-patient communication (PPC) skills 25 and one item that assessed patient satisfaction with care. The item assessing patient satisfaction, “How satisfied were you with the clinical service today?” was measured using a 3-point Likert scale (1. very satisfied/satisfied, 2. neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, 3. dissatisfied/very dissatisfied, 4. don't know). PPC skills 25 measured perceptions about clinicians’ communication skills during a clinical encounter with 16 items with responses on a 3-point Likert scale (lowest score = 16, highest score = 48). The PPC scale was previously validated among adult HIV patients in Kenya and showed acceptable validity (construct and content) and reliability. Internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = 0.81) and one-week test-retest reliability (Pearson Correlation = 0.82) were both acceptable. 25

In addition, we assessed the following domains: socio-demographic characteristics, knowledge about HIV and HIV treatment, and medication self-efficacy (HIV Self-Efficacy). 26 The selection of these constructs was informed by our previous qualitative work7,27 and were considered potential confounders of the relationship between PPC skills and patient satisfaction with care. Socio-demographic characteristics included age in years, sex (male vs female), years in HIV care and disclosed HIV status to anyone (yes vs no). Correct knowledge about HIV and HIV treatment included: correct knowledge of VL (yes vs no), correct definition of VL (yes vs no), correct frequency of VL tests based on their care plan (yes vs no), correct knowledge of their most recent VL count (yes vs no), and correct antiretroviral (ARV) timing according to their prescription (yes vs no). Medication self-efficacy 28 measured individual's efficacy to adhere to their medication, including 7 items with responses on a 3-point Likert scale (highest score = 21).

This survey instrument was first developed in English and then translated to Swahili. The survey was piloted among a predetermined number of n = 10 patients with unsuppressed viral load, who were not part of the main study sample. Following the pilot, revisions were made to clarify any items that participants had difficulty answering or were unclear. These changes mainly focused on the language (following the translation question from English to Swahili) and flow of questions in order to enhance understanding.

Recruitment and Data Collection

Using the AMPATH care data system, outreach workers (HIV positive peers) were issued with a list of patients who meet the eligibility criteria by the clinical team. The outreach workers contacted eligible patients to inform them about the study and invite them to participate. Patients who accepted the invitation to take part in the study were directed to a trained research assistant who provided detailed information about the study at the end of their clinic appointment. Only those who provided written informed consent were enrolled. Thereafter, the survey was administered in either English or Swahili, to consenting participants by trained research assistants in a private room at the respective clinics. Transport reimbursement of KES 500/USD 5 was given to patients who participated in the study.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics such as frequencies and the corresponding percentages were used to summarize categorical variables describing the study sample, while median and interquartile range (IQR) were used to summarize continuous variables.

Clinician PPC skills was considered as a continuous variable. The internal consistency of this scale was high (Cronbach's alpha = 0.89). Patient satisfaction with HIV care was transformed into a binary variable: satisfied (very satisfied/satisfied) versus dissatisfied (neither satisfied nor dissatisfied and dissatisfied/very dissatisfied). For medication efficacy (Cronbach's alpha = 0.63) we transformed the scores into a binary variable using cut-points defined by the distribution of scores. Scores in the highest quartile of medication efficacy were considered as high medication self-efficacy.

Logistic regression analysis was used to assess the association between clinician PPC skills (main exposure) and patient satisfaction (outcome variable). We first explored bivariate associations between our independent and outcome variable. Thereafter we examined the association between clinician PPC skills and patient satisfaction with care, accounting for potential confounders. We adjusted for age in years, sex (male vs female), marital status (single/divorced/widowed vs married/partnered), level of education (primary education or less vs secondary education or more), correct knowledge of most recent VL count (no vs yes), and medication self-efficacy (yes vs no). We excluded variables with limited variability, multicollinearity and a high proportion of missingness (>10%) from adjusted analysis. All statistical tests were conducted at p ≤ 0.05 level of significance using R (version 3.6.3).

Results

Study Sample Characteristics

Of the 360 eligible patients contacted, 328 (91.1%) were recruited and participated in the study. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the study participants. Overall, the mean age of participants was 48.2 years (Standard deviation [SD]: 12.1). The study sample was predominantly female (56%) and married/partnered (60%) and receiving care from study site 1 (69%). In addition, those having at least a primary level of education (82%), walking 30 min and more to their HIV facility (59%) and having disclosed their HIV status (99%) were the majority. In terms of knowledge of their HIV care, slightly more than half reported to have knowledge of what a viral load (VL) was, and among those, the majority (74%) provided the correct definition of a VL. About half (54%) of the participants correctly stated how often their VL test was taken and 59% had the correct knowledge of their most recent viral load count. Almost all (99%) of the participants provided the correct timing of when they were expected to take their ARV medication; however, none could name the ARV medication they were taking.

Table 1.

Patient Sociodemographic and HIV Care Knowledge Characteristics among Unsuppressed Patients.

| Characteristics | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, in years | 48.22 (12.05) | |

| Years in HIV care | 9.21 (3.64) | |

| N (%) | ||

| Health facility | Khunyangu | 220 (69) |

| Port Victoria | 108 (31) | |

| Female | 183 (55.8) | |

| Marital Status | Single/divorced/widowed | 130 (39.6) |

| Married/partnered | 198 (60.4%) | |

| Travel time to clinic | Missing | 64 (19.5) |

| <30 min | 70 (21.3) | |

| 30 to 60 min | 65 (19.8) | |

| <1 to 2 hrs | 92 (28.0) | |

| >2 hrs | 37 (11.3) | |

| Education level | None | 38 (11.6) |

| Primary level or less | 231 (70.4) | |

| Secondary education | 55 (16.8) | |

| Tertiary level and above | 4 (1.2) | |

| Disclosed HIV status | 324 (98.8) | |

| Knowledge of HIV care | Knowledge of VL | 215 (65.5) |

| Correct definition of VL | 160 (74.4) | |

| Correct frequency of VL tests | 177 (54.0) | |

| Correct knowledge of most recent VL count | 98 (58.7) | |

| Correct knowledge of ARV timing | 323 (99.1) | |

Relationship Between Clinician PPC Skills and Patient Satisfaction with HIV Care

Generally, a high proportion 278 (85%) of participants reported to be satisfied with the HIV services they received. The mean score on clinician PPC skills was 33.3 [standard deviation (SD) = 9.0].

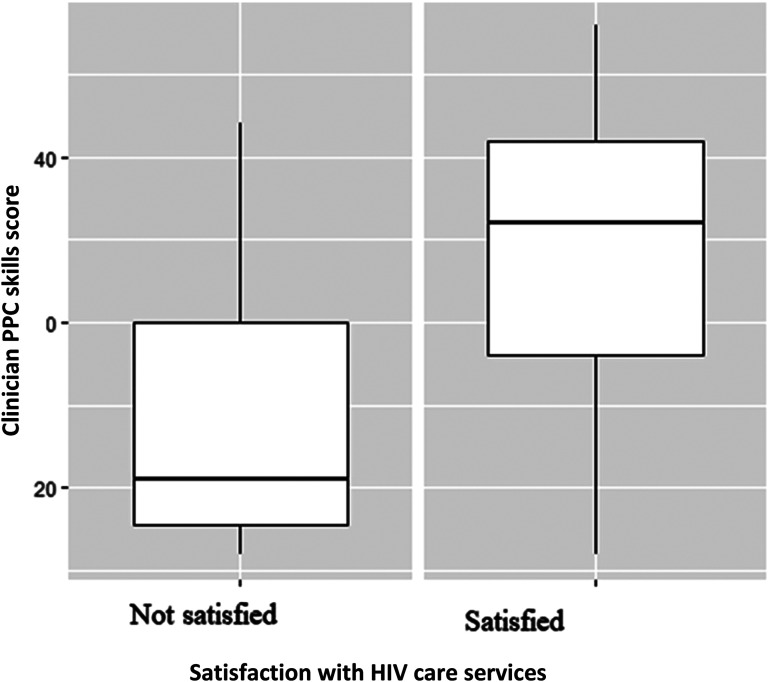

Participants who were satisfied with care reported higher clinician PPC skills (mean score = 35.02 [SD = 8.22]), compared to those who were not satisfied with care (mean = 23.44; SD = 7.04) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Clinician PPC skills mean scores by patient satisfaction with HIV care services among unsuppressed HIV patients.

Table 2 shows that in the unadjusted analysis, for every one unit increase in clinician PPC skills score, the odds of being satisfied with care increased by 19% (OR = 1.19, 95% CI: 1.14-1.26). This relationship was the same after adjusting for age, marital status, education level, years in care, correct knowledge of the most recent VL count, and medication self-efficacy [Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 1.19; 95% CI, 1.11 to 1.30].

Table 2.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Odds Ratios of Patient Satisfaction with Care and Clinician PPC Skills, and Other Characteristics among Unsuppressed HIV Patients.

| Variables | UOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Clinician PPC skills score, per unit | 1.19 (1.14-1.26) | 1.19 (1.11-1.30) |

| Age, in years | 0.99 (0.97-1.02) | 1.00 (0.96-1.05) |

| Female (vs male) | 0.74 (0.39-1.36) | 1.70 (0.53-5.73) |

| Married/coupled (vs Single/divorced/widowed) | 1.14 (0.61-2.10) | 0.80 (0.25-2.50) |

| Secondary education or higher (vs Primary education or less) | 1.43 (0.64-3.63) | 0.45 (0.11-1.89) |

| Years in HIV care | 1.01 (0.93-1.10) | 1.04 (0.89-1.20) |

| Correct knowledge of the most recent VL count (No vs Yes) | 0.53 (0.22-1.28) | 0.64 (0.20-1.97) |

| Medication self-efficacy (High vs Low)? | 1.73 (0.87-3.70) | 1.00 (0.32-3.38) |

Unadjusted Odds Ratio (UOR)

Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR)

Discussion

Our study revealed that patients’ assessments of clinicians’ PPC skills was positively associated with patient satisfaction with care among adult HIV patients with unsuppressed VL. We also observed that a high proportion of participants reported satisfaction with their HIV care. These findings are critical for informing HIV care programs on the importance of PPC skills in improving the quality of service delivery and overall patient satisfaction with care.6,9

Similar to our findings, other studies have found a direct positive relationship between PPC skills and patient satisfaction.11,13,15,17–19,22 Patients who reported that their clinicians had better communication skills also reported to be satisfied with care. This highlights the importance of PPC skills as the core in clinical practice and a key component of patient-centered care that promotes patient satisfaction with care.4,20,21 Following the benefits reported among HIV patients satisfied with care including ART adherence10–12 there is need for HIV care programs in this region to promote better interaction between providers and their patients through enhanced PPC skills.

The overall clinician PPC skills mean score was lower than what had been previously reported among HIV patients in the same region, 29 which is likely explained by the design of the trial from which our data are taken. Participants in the trial all had unsuppressed VL and hence the views of the virally suppressed patients may not be reflected in our data. Meanwhile, amidst the financial, human resource and structural challenges health systems in the region face,4,5 on-the-job trainings could be one of the approaches recommended to ensure that clinicians improve on their PPC skills. 30 In addition, the use of standard patient actors, successfully piloted among providers offering HIV care to young adults in Kenya, could be adopted to improve clinicians’ PPC skills. 31 This will not only promote better patient satisfaction with care, but ultimately improve on patient health outcomes. 22

Similar to other studies across the region,11,13,14,32 we found that a majority of our participants were satisfied with the HIV care they were receiving at their respective health facilities. It is however important to note that satisfaction is greatly influenced by socioeconomic status. 13 A study in Nigeria noted that individuals of a high economic status were less likely to attend public hospital as well as be satisfied with care. 13 Thus patients in public facilities were more satisfied with HIV care compared to those in private facilities. 13 Majority of the participants in our study had a less than secondary level of education and were receiving HIV care free of charge at rural public health facilities. This may reflect on their low socioeconomic status. Given its impact on patient health outcomes,10–12 additional studies with a wider category of HIV patients may also be needed to provide a holistic perspective patient satisfaction and its association with PPC skills in this population.

Finally, it is important to note that none of our study participants could accurately name the ARV medications they were receiving. Studies in developed countries have also documented inaccurate reporting of ARV medication among patients living with HIV. 33 In our context, this could be partly due to the low level of education among study participants and the complex names assigned to ARV medications. Given that patient ARV knowledge is key to medication adherence, 33 there may be need for HIV care programs to identity simpler ways for patients to correctly recall their medication. Efforts to promote and maintain patients’ active involvement in HIV care should also be continuously encouraged.

There are several study limitations. Generally, patient satisfaction with care as a construct may be difficult to measure since it varies over time and circumstances. 8 In addition, the surveys were conducted in the health facilities where participants received their routine HIV care which may have introduced social desirability bias. Furthermore, our study design and eligibility criteria limited our analysis, hence we could not explore the relationship between patient satisfaction and treatment outcomes. We also did not account for clinicians’ experiences and communication skills that may have influenced the PPC dynamics. Finally, although we sampled HIV patients receiving care from public HIV clinics, the clinics we selected were part of the AMPATH program. The way AMPATH provides care may differ from other HIV care programs in Kenya hence our results may not be generalizable to other rural settings in Kenya. Despite these challenges our study adds to the body of literature on the value of patient satisfaction in HIV care and the important factors to consider.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study showed that clinician PPC skills were associated with patient satisfaction with care among virally unsuppressed adult HIV patients. Promoting better provider-patient interactions may be key to improving patients’ level of satisfaction with the HIV services offered. Training of providers on effective PPC skills is an initial step towards achieving this goal. Additional research is needed to better understand approaches to improve PPC skills in an effort to enhance the experiences patients have with their HIV care facilities.

Author Biographies

Juddy Wachira is a senior lecturer at the department of Mental Health and Behavioral Science, School of Medicine, Moi University, Eldoret Kenya. She holds a PhD in Health Behavior from Indiana University, USA, a Master's degree in Public Health from Moi University, Kenya, and a Bachelor's degree in Education Home science and Technology from Moi University, Kenya. Her research interests are focused on understanding and promoting patient-centered care in HIV care settings in Kenya. Her research work has so far involved exploring the interpersonal and system level factors including provider, patient dynamics, peer involvement, and clinic structures that influence patients' outcomes in Kenya. She has also engaged in research work beyond HIV care that includes sexual health and breast and cervical cancer. She is a recipient of the Emerging Global Leader Award NIH-K43 to apply a mixed methods approach to assess the feasibility and acceptability of enhanced patient care among unsuppressed patients in western Kenya.

Ann Wanjiru Mwangi holds a PhD from Brown University, RI, USA, two master's degrees (Biostatistics and Applied Statistics) from Hasselt University in Belgium and also a Bachelor of Science degree from JKUAT, Kenya. She is an Associate Professor of Biostatistics, Moi University, and currently the acting Director Institute of Biomedical Informatics at Moi University. She is involved in training and supervising undergraduate and graduate students at Moi University. She is the co-Director of the Academic Model Providing Access to Health Care (AMPATH) Data and Analysis Team where she has been a Biostatistician for a period of over 15 years during which period several papers have been published in peer-reviewed journals. Her research interests are in Causal Inference, methods for addressing bias when using observational data for clinical decision making in resource-limited setting where clinical trials data are minimal, Missing data, Data mining, Multilevel modelling and Survival analysis with application in HIV & AIDS, Oncology and Chronic Disease among others. She is a Co-Investigator on several funded grants in Western Kenya.

Diana Chemutai is Public Health professional with over nine years' experience in research, health promotion and health education. She is passionate about improving health and health services at the community level by informing, educating, and empowering people about their health issues. She has a working knowledge of low resource settings having worked in a community health and prevention program as an intern in Lokichogio, Turkana, and as a community Project Officer in the rural areas of Rift valley Kenya. After working in these institutions, she transitioned into research at the Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH) as a Research Assistant, where she acquired invaluable experience in data collection, data quality management, capacity building, maintenance of records, training, leadership and coordination.

Monicah W. Nyambura is a Public Health Data Analyst. She holds a Bachelors degree in Computer science and Mathematics with a major in Statistics. Monicah has over 10 years of experience in data management and analysis in health research. Monicah is passionate about leadership and mentorship. She is focused on practical solutions to making a difference in society. She is recipient of the 2015 Social Entrepreneurs Transforming Africa Leadership Award.

Becky L. Genberg is an Associate Professor in the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health's Department of Epidemiology. She received her PhD in Epidemiology (2010) and an MPH with a concentration in Population and Family Health Sciences (2002) from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. She completed post-doctoral training at the Brown University School of Public Health in 2012. She practices social epidemiology, focusing her research on the social determinants driving health behaviors and outcomes and leveraging the methods of implementation science to examine the multilevel influences of HIV treatment outcomes in resource-limited settings. Her current research focuses broadly on the longitudinal relationships between structural factors and individual behaviors related to engagement in HIV care and the social context of substance use. Her research is nested within the Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH) consortium based in Eldoret, Kenya and the AIDS Linked to the IntraVenous Experience (ALIVE) cohort of people who inject drugs in Baltimore.

Wilson is Professor of Health Services, Policy & Practice, Professor of Medicine, and Chair of the Department of Health Services, Policy & Practice at the Brown University School of Public Health. He has three broad areas of research: medication adherence, health services research related to HIV care, and physician patient communication. Regarding medication adherence, he has developed new self-report adherence measures, done clinical trials of interventions to improve medication adherence, and worked with large commercial and Medicaid pharmacy claims databases. He is also interested in using behavioral economic methods to improve adherence and other medical outcomes. Over the last decade, He and colleagues have conducted a number of studies to develop new methods to understand physician-patient communication in HIV and other chronic conditions, and to test provider-focused interventions to improve communication quality. He is also the Co-Director of the Developmental Core of the Providence-Boston Center for AIDs Research (CFAR).

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions: All authors aided in the conceptualization of the manuscript. JW developed the initial drafts. JW, AM, BG and IW reviewed and edited the manuscript for publication. All authors reviewed the final drafts and approved the manuscript for submission.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Institute of Health (grant number K43TW010684, U54GM115677, P30AI042853).

ORCID iDs: Juddy Wachira https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3654-5788

Becky Genberg https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9450-5311

References

- 1.Watt N, Sigfrid L, Legido-Quigley H, et al. Health systems facilitators and barriers to the integration of HIV and chronic disease services: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(suppl_4):iv13–iv26. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czw149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wachira J, Naanyu V, Genberg B, et al. Health facility barriers to HIV linkage and retention in western Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):646. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0646-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Genberg B, Wachira J, Kafu C, et al. Health system factors constrain HIV care providers in delivering high-quality care: perceptions from a qualitative study of providers in western Kenya. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2019;18:232595821882328. doi: 10.1177/2325958218823285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Man JD, Mayega RW, Sarkar N, et al. Patient-centered care and people-centered health systems in sub-Saharan Africa: why so little of something so badly needed? Int J Pers Cent Med. 2016;6(3):162–173. doi: 10.5750/IJPCM.V6I3.591 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barker C, Dutta A, Klein K. Can differentiated care models solve the crisis in HIV treatment financing? analysis of prospects for 38 countries in sub-Saharan Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(Suppl 4):21648. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.5.21648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogus TJ, McClelland LE. When the customer is the patient: lessons from healthcare research on patient satisfaction and service quality ratings. Hum Resour Manag Rev. 2016;26(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2015.09.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wachira J, Genberg B, Kafu C, Braitstein P, Laws MB, Wilson IB. Experiences and expectations of patients living with HIV on their engagement with care in western Kenya. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:1393–1400. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S168664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berkowitz B. The patient experience and patient satisfaction: measurement of a complex dynamic. Online J Issues Nurs. 2016;21(1)1–9. doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol21No01Man01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng JHY, Luk BHK. Patient satisfaction: concept analysis in the healthcare context. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(4):790–796. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Ruthia YS, Hong SH, Graff C, Kocak M, Solomon D, Nolly R. Examining the relationship between antihypertensive medication satisfaction and adherence in older patients. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2017;13(3):602–613. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mukamba N, Chilyabanyama ON, Beres LK, et al. Patients’ satisfaction with HIV care providers in public health facilities in Lusaka: a study of patients who were lost-to-follow-up from HIV care and treatment. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(4):1151–1160. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02712-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dang BN, Westbrook RA, Black WC, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Giordano TP. Examining the link between patient satisfaction and adherence to HIV care: a structural equation model. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Umeokonkwo CD, Aniebue PN, Onoka CA, Agu AP, Sufiyan MB, Ogbonnaya L. Patients’ satisfaction with HIV and AIDS care in anambra state, Nigeria. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0206499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Jager GA, Crowley T, Esterhuizen TM. Patient satisfaction and treatment adherence of stable human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients in antiretroviral adherence clubs and clinics. Afr. J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2018;10(1):1–8. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v10i1.1759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devnani M, Gupta AK, Wanchu A, Sharma RK. Factors associated with health service satisfaction among people living with HIV/AIDS: a cross sectional study at ART center in Chandigarh. India. AIDS Care - Psychol Socio-Med Asp AIDS/HIV. 2012;24(1):100–107. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.592816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richey LE, Halperin J, Pathmanathan I, Van Sickels N, Seal PS. From diagnosis to engagement in HIV care: assessment and predictors of linkage and retention in care among patients diagnosed by emergency department based testing in an urban public hospital. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014;28(6):277–279. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vranceanu AM, Ring D. Factors associated with patient satisfaction. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(9):1504–1508. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan LM, Stein MD, Savetsky JB, Samet JH. The doctor-patient relationship and HIV-infecfed patients’ satisfaction with primary care physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(7):462–469. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.03359.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang S. Pathway linking patient-centered communication to emotional well-being: taking into account patient satisfaction and emotion management. J Health Commun. 2017;22(3):234–242. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2016.1276986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70(4):351–379. doi: 10.1177/1077558712465774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McMillan SS, Kendall E, Sav A, et al. Patient-Centered approaches to health care: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70(6):567–596. doi: 10.1177/1077558713496318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oetzel J, Wilcox B, Avila M, Hill R, Archiopoli A, Ginossar T. Patient–provider interaction, patient satisfaction, and health outcomes: testing explanatory models for people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2015;27(8):972–978. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1015478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mcintosh, Ian and Kamaara, Eunice. AMPATH: A Strategic Partnership in Kenya (March 1, 2016). Global Perspectives on Strategic International Partnerships, Institute of International Education, 2016. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2768205. Accessed June 5, 2020.

- 24.Wachira J, Genberg B, Chemutai D, et al. Implementing enhanced patient care to promote patient engagement in HIV care in a rural setting in Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/S12913-021-06538-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wachira J, Middlestadt S, Reece M, Peng C-YJ, Braitstein P. Psychometric assessment of a physician-patient communication behaviors scale: the perspective of adult HIV patients in Kenya. AIDS Res Treat. 2013;2013: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shively M, Smith TL, Bormann J, Gifford AL. Evaluating self-efficacy for HIV disease management skills. AIDS Behav. 2002;6(4):371–379. doi: 10.1023/A:1021156914683 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wachira J, Genberg B, Kafu C, et al. The perspective of HIV providers in western Kenya on provider-patient relationships. J Health Commun. 2018;23(6):591–596. 10.1080/10810730.2018.1493061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson MO, Neilands TB, Dilworth SE, Morin SF, Remien RH, Chesney MA. The role of self-efficacy in HIV treatment adherence: validation of the HIV treatment adherence self-efficacy scale (HIV-ASES). J Behav Med. 2007;30(5):359–370. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9118-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wachira J, Middlestadt S, Reece M, Peng C-YJ, Braitstein P. Physician communication behaviors from the perspective of adult HIV patients in Kenya. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(2):190–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conn VS, Ruppar TM, Enriquez M, Cooper PS, Chan KC. Healthcare provider targeted interventions to improve medication adherence: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69(8):889–899. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mugo C, Wilson K, Wagner AD, et al. Pilot evaluation of a standardized patient actor training intervention to improve HIV care for adolescents and young adults in Kenya. AIDS Care. 2019;31(10):1250–1254. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2019.1587361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dang BN, Westbrook RA, Njue SM, Giordano TP. Building trust and rapport early in the new doctor-patient relationship: a longitudinal qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-0868-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brouwer ES, Napravnik S, Smiley SG, Corbett AH, Eron JJ. Self-report of current and prior antiretroviral drug use in comparison to the medical record among HIV-infected patients receiving primary HIV care. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(4):432–439. doi: 10.1002/PDS.2096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]