Abstract

Increasing home dialysis prevalence is an international priority. Many patients start peritoneal dialysis, then transition to hemodialysis after complications. New strategies are needed to support modality persistence. Health mindset refers to individual belief about capacity to change to improve health. Mindset was measured in a cross-section of 101 adult peritoneal dialysis patients from April 2019 to June 2020. The Health Mindset Scale was administered to characterize the continuum of fixed vs. growth mindset with respect to health. Health literacy and health self-efficacy were also assessed. Participants were 43% female, 32% African American, and 42% diabetic. Health mindset scores were skewed toward growth (range 3–18), with average (SD) 12.83 (4.2). Growth mindset was strongly associated with health self-efficacy. Adults receiving peritoneal dialysis report health mindset variation. Growth mindset and health self-efficacy correlation suggests measurement of similar constructs, demonstrating convergent validity. The Health Mindset Scale may identify individuals who could benefit from targeted interventions to improve mindset, and foster peritoneal dialysis modality persistence.

Keywords: peritoneal dialysis, mindset, patient education, dialysis training

Introduction

There is international interest in increasing home-based dialysis therapies to reduce the worldwide dialysis burden (1). Patients approaching end-stage kidney disease who choose home dialysis using peritoneal dialysis perform their treatments at home without a nurse, either on their own or with a helper. Physical and clinical factors influence whether a patient can do peritoneal dialysis at home. These factors include peritoneal membrane characteristics (2), space for supplies (3), and the placement and maintenance of a peritoneal dialysis catheter (4, 5). Patient psychology and behavior may be of particular importance in peritoneal dialysis, as patients are doing their own life-saving treatments day after day. The biopsychosocial model is a framework for understanding how patient subjective experience contributes to health outcomes (6, 7). Patient psychology has been linked to clinical outcomes in several settings. Higher quality of life scores in cancer patients are associated with better survival (8). In heart failure patients, a positive-psychology-based intervention led to improvements in both well-being and health-behaviour outcomes (9). The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study provides evidence for the impact of psychosocial factors on morbidity and mortality (10). Variation in how peritoneal dialysis is taught has been associated with differences in peritonitis risk (11). Psychology and educational theory that are effective in other settings may be relevant to peritoneal dialysis training and success.

Mindsets are groups of beliefs or assumptions that affect individual perceptions and actions (12). Mindset theory describes two general categories: fixed and growth. A fixed mindset is the belief that ability and intelligence cannot develop or improve. A growth mindset reflects belief that knowledge and ability can change and grow over time. The positive effect of a growth mindset on outcomes has been shown in a variety of professional, academic, and healthcare settings (13). Students with a growth mindset are more likely to persist to learn a new task, such as an arithmetic problem, and demonstrate better test performance (14). Home dialysis patients must learn dialysis procedures knowing that their mistakes could cause themselves harm. Mindset constructs related to learning and health outcomes may be especially relevant for home dialysis patients.

This study describes mindset in adult peritoneal dialysis patients using the Health Mindset Scale (HMS), previously the Health Belief Scale, a three-item Likert-based scale derived from the original mindset assessment instrument (13, 15, 16). The HMS was administered with the Perceived Health Competance Scale (PHCS), an established instrument for measuring health self-efficacy (17), and with the three-item Brief Health Literacy Screen (BHLS), a validated instrument associated with kidney knowledge and mortality (18,19). The PHCS and BHLS were administered with the HMS for validation. We hypothesized that HMS scores would positively correlate with the PHCS and the BHLS.

Methodology

Study Population

We enrolled 102 incident and prevalent peritoneal dialysis patients from our institution’s Home Dialysis Unit from April 2019 to June 2020. Participants were adults ages ≥18, spoke fluent English or had a caregiver present to translate, had a peritoneal dialysis catheter, and were followed at our institution’s Home Dialysis Unit. Urgent start patients were defined as patients who had a peritoneal dialysis catheter placed in the hospital and used before discharge. Traditional start patients had a catheter placed that healed for at least 2 weeks, and was then used on an outpatient basis. Participants were identified by a review of clinic appointment rosters and in consultation with providers, and enrolled sequentially. Our institution’s Review Board approved all study procedures prior to participant enrollment. Participants provided written informed consent and did not receive monetary compensation.

Data Collection

The principal investigator or a trained assistant administered surveys during hospitalizations or scheduled appointments. Demographic information was collected from participants at the time of survey administration. Vintage was defined as time since the peritoneal dialysis catheter was placed, as patient catheter care begins at placement.

For mindset related to health, patients were surveyed using the previously employed HMS. Participants were instructed to report their agreement with statements about health on a six-point Likert Scale (ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”). Responses were added and analyzed on a scale from 3 to 18, with higher numbers indicating growth mentality.

For health self-efficacy, patients were administered three questions from the PHCS (17): participants were instructed to report their agreement with each of the statements on a six-point Likert Scale (ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”). After reverse-coding the two negatively worded items, responses were added and analyzed on a scale from 3 to 18, with higher numbers indicating greater participant health self-efficacy. The PHCS is a domain-specific measure of the degree to which an individual feels capable of effectively managing their health outcomes. This instrument was chosen to test whether patient perception of their health management ability would positively correlate with their belief that they could learn and perform dialysis, consistent with a growth mindset.

Health literacy was assessed with the BHLS. The BHLS questions are scored on a five-point ordinal response scale and summed to produce a score ranging from 3 to 15. Higher scores indicate higher patient self-perceived health literacy. This instrument was chosen to test the hypothesis that patients who were more confident using written health materials would also be more confident that they could learn dialysis procedures, consistent with growth mindset.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed for the overall sample, and for each instrument (Table 1). Results for the three instruments are presented as means, standard deviations (SD), and medians with interquartile ranges for individual items, and overall for behavior measures (Table 2). Chi-squared tests examined cross-sectional associations between the mean score for each patient characteristic and behavior measures. Cronbach’s alpha estimated the reliability of each instrument. Associations between mindset scores and health self-efficacy and health literacy scores were tested by calculating the Spearman’s ρ with bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Statistical tests were performed using R version 4.0.1.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics and Association With Average Scores for Health Mindset, Health Self-Efficacy, and Health Literacy, by Instrument.

| Health mindset scale | Perceived health competence scale | Brief health literacy screen | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All subjects | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Characteristic (N = 101) | 12.8 (4.2) | 13.3 (3.3) | 12.6 (2.7) | |

| Age | ||||

| 18-48 | 32% | 12.4 (3.9) | 13.1 (2.8) | 13.1 (1.8) |

| 48-61 | 35% | 13.5 (4.0) | 13.8 (3.1) | 12.9 (2.6) |

| >61 | 34% | 12.6 (4.6) | 12.9 (3.7) | 11.7 (3.3) |

| P value | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.06 | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 43% | 12.0 (4.3) | 13.3 (3.3) | 12.8 (2.5) |

| Male | 58% | 13.4 (4.1) | 13.3 (3.2) | 12.4 (2.9) |

| P value | 0.08 | 0.93 | 0.43 | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| African American | 32% | 12.9 (4.3) | 14.2 (2.7) | 13.0 (2.1) |

| Caucasian | 63% | 12.8 (4.2) | 13.0 (3.5) | 12.4 (2.8) |

| Hispanic/other | 5% | 12.4 (4.6) | 11.6 (1.9) | 12.2 (5.2) |

| P value | 0.96 | 0.1 | 0.6 | |

| Education | ||||

| High school | 25% | 10.6 (4.5) | 12.4 (3.9) | 11.6 (3.6) |

| College | 52% | 13.7 (3.5) | 13.9 (2.6) | 12.6 (2.5) |

| Additional/other | 23% | 13.4 (4.5) | 12.9 (3.5) | 13.5 (1.9) |

| P value | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.04 | |

| Prior HD | ||||

| Hemodialysis (HD) prior to peritoneal dialysis (PD) | 30% | 12.9 (4.6) | 13.4 (3.2) | 13.3 (1.7) |

| No HD prior to PD | 70% | 12.8 (4.1) | 13.2 (3.3) | 12.3 (3.0) |

| P value | 0.95 | 0.83 | 0.08 | |

| Start type | ||||

| Urgent start | 17% | 11.6 (4.4) | 12.8 (3.6) | 12.6 (2.4) |

| Traditional start | 83% | 13.1 (4.1) | 13.4 (3.2) | 12.5 (2.8) |

| P value | 0.21 | 0.52 | 0.89 | |

| New vs. prevalent patient | ||||

| 90 Day incident patients | 22% | 12.8 (4.3) | 13.1 (3.2) | 12.5 (2.7) |

| Prevalent patients | 78% | 13.1 (4.0) | 14.1 (3.3) | 12.8 (2.8) |

| P value | 0.74 | 0.19 | 0.63 | |

| Help at home with PD | ||||

| Has help with PD at home | 65% | 12.8 (4.1) | 13.2 (3.2) | 12.2 (2.9) |

| No help with PD at home | 35% | 13.0 (4.4) | 13.5 (3.3) | 13.2 (2.4) |

| P value | 0.81 | 0.71 | 0.09 |

P < 0.05 are in bold.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for the three instruments.

| Item | Mean (SD) | Median (interquartile range) |

|---|---|---|

| Health mindset scale | ||

| 1. Your body has a certain amount of health, and you really can’t do much to change it a | 4.4 (1.6) | 5 (3, 6) |

| 3. Your health is something about you that you cannot change very much a | 4.3 (1.6) | 5 (3, 6) |

| 5. You can try to make yourself feel better, but you really can’t change your basic health a | 4.1 (3,5) | 4 (3, 5) |

| Health mindset scale total | 12.8 (4.2) | 14 (9.8, 17.0) |

| Health self-efficacy scale | ||

| 2. It is difficult for me to find effective solutions for health problems that come my way b | 4.7 (1.4) | 5 (4, 6) |

| 4. I’m generally able to accomplish my goals with respect to my health c | 4.9 (1.2) | 5 (5, 6) |

| 6. No matter how hard I try, my health doesn’t turn out the way I would like b | 3.8 (1.7) | 4 (3, 5) |

| Health self-efficacy scale total | 13.3 (3.3) | 13 (11, 16) |

| Health literacy screen | ||

| 7. How often do you have problems learning about your medical condition because of difficulty understanding written information? d | 4.3 (1.0) | 5 (4, 5) |

| 8. How confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself? e | 4.2 (1.0) | 5 (4, 5) |

| 9. How often do you have someone help you read hospital or other medically related materials? d | 4.0 (1.3) | 4 (4, 5) |

| Health literacy total | 12.6 (2.7) | 14 (11, 15) |

Strongly agree = 6; strongly disagree = 1.

Strongly agree = 1; strongly disagree = 6.

Strongly agree = 6; strongly disagree = 1.

Always = 1; often = 2; sometimes = 3; occasionally = 4; never = 5.

Not at all = 1; a little bit = 2; somewhat = 3; quite a bit = 4; extremely = 5.

Results

Among 175 eligible patients receiving peritoneal dialysis screened between April 2019 and June 2020, 35 were not eligible owing to their being less than 18 years old. Two patients refused to participate because of concern about participation in any clinical trial. One patient was screened and not included because of a non-dialysis-related catheter indication. Thirty-five were not approached because of scheduling issues. In total, 102 patients were enrolled. One patient left the study for unclear reasons, and was removed. There was no other missing data. Participant age range was 19–83 years old, with mean (SD) 51.9 (16.9) years. The sample was 43% female, 63% Caucasian and 32% African American, with 42% living with diabetes (Table 1). Mean albumin was 3.5 g/dL (SD 0.5 g/dL), and the median was 3.5 g/dL. Of the sample population, malignancy was present in 26%, ischemic heart disease in 26%, and neurologic disease other than dementia in 7%. Dialysis vintage ranged from 2 days to 96 months, with mean (SD) 19.4 (19.5) months, and 22% 90-day incident patients. Of the total sample, 30% had received hemodialysis prior to peritoneal dialysis, 17% were urgent start, and 65% reported having help with dialysis at home.

Health Mindset

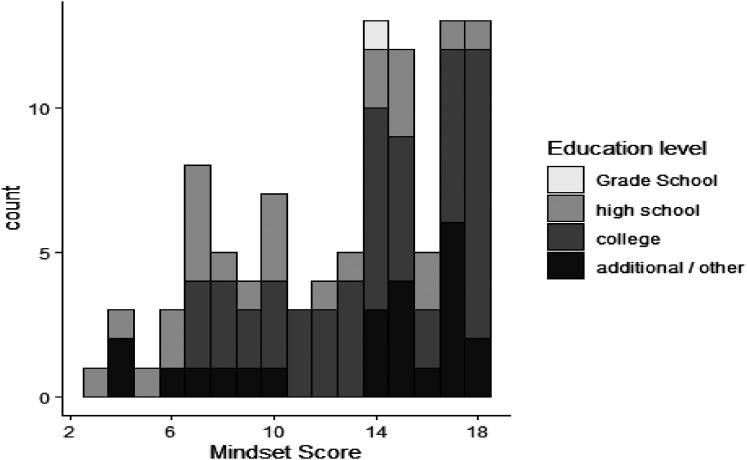

The average HMS score was 12.83, SD 4.2 (Figure 1). Cronbach’s alpha for the HMS scores was 0.84. Mean HMS scores were relatively evenly distributed by age tertile (Table 1). Males reported higher HMS scores (13.4) as compared with females (12.0, p = 0.08). Average HMS score distribution was significantly different for some levels of education. Patients with a high school education reported lower average mindset scores compared with patients with completed education beyond high school (high school 10.6 vs. college 13.7 vs. additional/other 13.4, p = 0.01; Table 1 and Figure 1). Differences in mean HMS scores by race, history of hemodialysis prior to peritoneal dialysis, history of urgent start peritoneal dialysis, dialysis vintage (90-day incident patients), or having help at home were inconclusive.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Health Mindset Scores and Education Level. Mean (SD): 12.83 (4.2); median [interquartile range]: 14.0 [9.8, 17.0].

Health Self-Efficacy and Health Literacy

The average score on the PHCS (range 3–18) was 13.3 (SD 3.3) (Tables 1 and 2). The Cronbach’s alpha for health self-efficacy in this sample was 0.64. PHCS scores were higher among African Americans, those who had completed college, and patients receiving dialysis for 3 months or more, although tests for the significance of these differences were inconclusive (Table 1). Higher scores on the PHCS were significantly associated with higher scores on the HMS, indicating positive correlation between higher health self-efficacy and a greater growth mindset (Spearman’s ρ = 0.65 [95% CI 0.52, 0.77]).

For health literacy, patients reported a mean subjective health literacy score of 12.6 (SD 2.7) on the Brief BHLS (Tables 1 and 2). BHLS scores differed significantly across educational groups. The participants with a high school education had the lowest observed mean scores (high school 11.6 vs. college 12.6, vs. additional/other 13.5 (p = 0.04)). BHLS scores were higher in patients who reported no help at home, but this result was inconclusive. Correlation between scores on the HMS and the BHLS was also inconclusive (r = 0.17).

Discussion

Increasing home dialysis is a national priority (1, 20). Initiation on peritoneal dialysis does not guarantee modality persistence. In a recent retrospective study of 29,573 incident peritoneal dialysis patients followed for a median of 21.6 months, 25.9% died, 17.1% underwent kidney transplant, and only 15.8% continued to be followed on peritoneal dialysis (21). An astoundingly high 41.2% transferred to hemodialysis within the median study period of 21.6 months. Approximately 40% of patients reported peritonitis, with a higher rate of transfer to hemodialysis. Transition from peritoneal dialysis to hemodialysis increases mortality risk (22–26) and can be costly (27). After decades of experience training peritoneal dialysis patients, there is still a high percentage of abrupt and unplanned transfers to hemodialysis in the United States (21). New ideas are needed to support peritoneal dialysis training and long-term modality success. The construct of mindset, a belief that a person’s situation, knowledge, or abilities can change, is applicable to a broad range of health care settings (12, 16, 29). This study introduces mindset as a novel concept for understanding cognition, psychology, and decision-making in peritoneal dialysis patients.

A key finding is variation in mindset. The range in HMS scores means that it will be possible to examine associations with clinical outcomes. Differences in mindset by important social determinants such as education level and gender were also suggested. The association between growth mindset and educational attainment beyond high school seems reasonable. Higher education requires learning new skills and persistence in the face of difficult tasks, which are characteristics of a growth mindset (13). Larger samples are needed to rigorously examine associations between variation in mindset and subgroups of patients.

The Cronbach’s alpha supports internal validity for the three-item HMS (30). the HMS correlation with PHCS scores also suggests concurrent validity. This makes sense, as health self-efficacy, or confidence in performing a goal-directed health-related activity, seems well aligned with the growth mindset belief that a new task can be learned (31). Interestingly, there was no association between health mindset and health literacy. Higher subjective health literacy may not be the primary driver of successful home dialysis, which is dominated by visual and spatial cues. Peritoneal dialysis training emphasizes in-person, hands-on training with a nurse, with less emphasis on understanding written materials. Furthermore, asking for help to understand written materials leads to a lower BHLS score, but may actually indicate a greater growth mindset.

This study has limitations. The study may not have been powered to demonstrate statistically significant associations between mindset and certain patient characteristics. It is a single-center study, and center traditions, beliefs, and processes that are uniform within this single center may contribute to bias and limit generalizability to other centers. Children were not included in this study, so generalizability to the pediatric population is also limited. Future studies that administer the survey at more than one center, and to a larger sample size, may begin to overcome these limitations. This study did not directly examine associations between mindset and specific patient behaviors or skills related to performing the peritoneal dialysis procedure. A fixed mindset may not actually lead to decreased patient competency in execution of components involved in successful self-management of peritoneal dialysis, such as performing tubing connections, or careful exit site care.

Conclusion

This initial, single-center study suggests that the HMS may be an internally consistent and valid measure of mindset among peritoneal dialysis patients that could contribute to understanding of how patients learn to do their own peritoneal dialysis procedures. The three-item HMS is a simple and brief instrument that can feasibly be administered within the time and logistical constraints of a busy outpatient peritoneal dialysis clinic. A large proportion of incident peritoneal dialysis patients transition to hemodialysis in the first 18 months after training (21). Novel interventions are needed to support peritoneal dialysis training and maximize patient success. This exploratory study presents empiric evidence linking the biopsychosocial model (6, 7) to peritoneal dialysis patients, through the novel theoretical construct of mindset (12, 13). If a growth mindset does align with more favorable clinical outcomes for peritoneal dialysis patients, then mindset may be considered as a target for behavioral interventions (14, 32, 33) to support maintenance of peritoneal dialysis in patients at high risk for poor health outcomes.

Authors’ Note

Portions of this work were shared in a poster presentation at the 2020 Annual Dialysis Conference, and at the 2020 American Society of Nephrology Annual Meeting. Written informed consent was obtained for all human subjects that participated in this study for their anonymous information to be published in this article. All of the experimental procedures involving humans were conducted in accordance with the Institutional Review Board guidelines of the Vanderbilt University Medical Center, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients, attendings, and nurses at the Vanderbilt Home Dialysis Unit for their interest, participation, and support. The authors also acknowledge Dr K. Wallston’s specific contributions to this manuscript, and are grateful for his mentorship.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: K. Cavanaugh is supported by NIH P30DK114809. D. Nair is supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality/Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute Learning Health Systems K12HS026395. R. Fissell is supported by a grant from the International Society of Peritoneal Dialysis.

ORCID iDs: Rachel B. Fissell https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1897-6429

Ebele M. Umeukeje https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2070-6433

Devika Nair https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7164-715X

Marcus Wild https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9702-6191

References

- 1.Li P, Cheung W, Lui S, et al. Increasing home-based dialysis therapies to tackle dialysis burden around the world: a position statement on dialysis economics from the 2nd Congress of the International Society for Hemodialysis. Hemodial Int. 2011; 15:10-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brimble KS, Walker M, Margetts P, et al. Meta-analysis: peritoneal membrane transport, mortality, and technique failure in peritoneal dialysis. JASN. 2006;17:2591-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sukul N, Zhao J, Fuller DS, et al. Patient-reported advantages and disadvantages of peritoneal dialysis: results from the PDOPPS. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20:116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crabtree JH, Chow K. Peritoneal dialysis catheter insertion. Semin Nephrol. 2017;37:17-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliver MJ, Perl J, McQuillan R, et al. Quantifying the risk of insertion-related peritoneal dialysis catheter complications following laparoscopic placement: results from the North American PD Catheter Registry. Perit Dial Int. 2020;40: 185-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borrell-Carrio F, Suchman AL, Epstein RM. The biopsychosocial model 25 years later: principles, practice, and scientific inquiry. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:576-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.George E, Engel L. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137:535-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sitlinger A, Zafar SY. Health-related quality of life, the impact on morbidity and mortality. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 2018;27:675-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Celano CM, Freedman ME, Harnedy LE, et al. Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a positive psychology-based intervention to promote health behaviors in heart failure: the REACH for health study. J Psychosom Res. 2020;139:110285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tentori F, Mapes DL. Health-related quality of life and depression among participants in the DOPPS: predictors and associations with clinical outcomes. Semin Dial. 2010;23:14-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonnal H, Bechade C, Boyer A, et al. Effects of educational practices on the peritonitis risk in peritoneal dialysis: a retrospective cohort study with data from the French peritoneal dialysis registry (RDPLF). BMC Nephrol. 2020;21:205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schroder HS. Mindsets in the clinic: applying mindset theory to clinical psychology. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;83:101957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dweck CS. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Ballantine Books; 2008:55-222. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blackwell LS, Trzesniewski K, Dweck C. Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: a longitudinal study and an intervention. Child Dev. 2007;78:246-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dweck CS, Chiu C, Hong Y. Implicit theories and their role in judgements and reactions: a world from two perspectives. Psychol Inq. 1995;6:267-85. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sujka J, St Peter S, Mueller C. Do health beliefs affect pain perception after pectus excavatum repair? Pediatr Surg Int. 2018;34:1363-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith MS, Wallston KA, Smith CA. The development and validation of the Perceived Health Competence Scale. Health Educ Res. 1995;10:51-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cavanaugh KL, Osborn CY, Tentori F, at al. Performance of a brief survey to assess health literacy in patients receiving hemodialysis. Clin Kidney J. 2015;8:462-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cavanaugh KL, Wingard RL, Hakim RM, et al. Low health literacy associates with increased mortality in ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1979-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan CT, Collins K, Ditschman EP, et al. Koester-Wiedemann L, Saffer TL, Wallace E, Rocco MV. Overcoming barriers for uptake and continued use of home dialysis: an NKF-KDOQI conference report. AJKD. 2020;75:926-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGill RL, Weiner DE, Ruthazer R, et al. Transfers to hemodialysis among US patients initiating renal replacement therapy with peritoneal dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;74:620-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pulliam J, Li NC, Maddux F, et al. First-year outcomes of incident peritoneal dialysis patients in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64:761-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al-Jaishi AA, Jain AK, Garg AX, et al. Hemodialysis vascular access creation in patients switching from peritoneal dialysis to hemodialysis: a population-based retrospective cohort. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67:811-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo A, Mujais S. Patient and technique survival on peritoneal dialysis in the United States: evaluation in large incident cohorts. Kidney Int Suppl. 2003;88:S3-S12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liberek T, Renke M, Skonieczny B, et al. Therapy outcome in peritoneal dialysis patients transferred from haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:2889-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szeto CC Kwan BC Chow KM, et al. Outcome of hemodialysis patients who had failed peritoneal dialysis. Nephron Clin Pract. 2010;116:c300-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chui BK, Manns B, Pannu N, et al. Health care costs of peritoneal dialysis technique failure and dialysis modality switching. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61:104-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mueller C, Rowe M, Zuckerman B. Mindset matters for parents and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:415-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int J Med Educ. 2011;2:53-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:143-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walton GM, Cohen GL. A brief social-belonging intervention improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science. 2011;331:1447-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeager DS, Hanselman P, Walton GM, et al. Carvalho CM, Hahn PR, Gopalan M, Mhatre P, Ferguson R, Duckworth AL, Dweck CS. A national experiment reveals where a growth mindset improves achievement. Nature. 2019;573:364-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]