Abstract

Patient: Male, 34-year-old

Final Diagnosis: Pericarditis

Symptoms: Chest pain • cough • fever • shortness of breath

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Infectious Diseases

Objective:

Mistake in diagnosis

Background:

Bacterial pericarditis can present a diagnostic challenge due to the difficulty of obtaining tissue for bacterial identification. This report is of a 34-year-old man who presented with fever and cough. Diagnosis was initially delayed without a tissue sample, but the patient was later found to have polymicrobial bacterial pericarditis.

Case Report:

A 34-year-old man from the Democratic Republic of Congo presented to the emergency room with cough, fever, and night sweats. He was admitted and found to have pericardial thickening and fluid collection with calcifications. A tissue sample was not obtained for diagnosis, and he was discharged on RIPE (rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol) and steroids for presumed tuberculosis pericarditis. He worsened clinically and was readmitted to the hospital with evolving pericardial effusion with air present, in addition to new pleural effusion and parenchymal consolidation. He subsequently underwent thoracotomy and pericardial biopsy. Tissue cultures and sequence-based bacterial analysis eventually revealed the presence of Prevotella oris and Fusobacterium nucleatum. He improved dramatically with appropriate antibiotic therapy.

Conclusions:

This report demonstrates the importance of undergoing further diagnostic work-up for bacterial pericarditis, especially in resource-rich settings. Although tuberculosis pericarditis should remain high on the differential, it is imperative not to anchor on that diagnosis. Instead, when feasible and safe, tissue biopsy should be obtained and sent for organism identification. AFB smears and cultures, Xpert MTB/RIF, and sequence-based bacterial analysis have all been used for identification. Delay in diagnosis can lead to progression of disease and unnecessary incorrect therapies.

Keywords: Bacterial Infections; Pericarditis; Pericarditis, Tuberculous; Pleural Effusion; Fever; Democratic Republic of the Congo; Pericardial Effusion; Coinfection

Background

Pericarditis, which is inflammation of the pericardium, is the most common pericardial disease encountered, accounting for approximately 0.2% of cardiovascular admissions [1]. The differential diagnosis of pericarditis is broad but can be narrowed by taking into account epidemiologic factors, medical history, and medications. Infectious causes of pericarditis may be due to direct infection (eg, caused by trauma or surgery), hematogenous spread, or contiguous extension from a thoracic or abdominal source [2]. In developing nations with a high tuberculosis burden, tuberculous pericarditis accounts for approximately 70% of cases of pericarditis, but in Western Europe less than 5% of pericarditis cases are due to tuberculosis [1]. Non-tuberculous bacterial pericarditis is estimated to cause 1–3% of diagnosed pericarditis [3]. With all etiologies, pericardial fluid or adjacent tissue sampling is imperative for a definitive diagnosis of bacterial pericarditis [4].

Here, we present a case of bacterial pericarditis that was initially misdiagnosed and treated as tuberculous pericarditis, only to be later diagnosed as pericarditis secondary to Prevotella oris and Fusobacterium nucleatum after clinical worsening on tuberculosis treatment.

Case Report

A 34-year-old African man with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency department with 2 months of progressive dry cough, fever, night sweats, and weight loss. He reported that his symptoms had initially begun during a 1-week trip to his home country, the Democratic Republic of Congo. He did not travel outside the city limits of Kinshasa or consume any new foods, and he was not exposed to any sick contacts, animal bites, or stings. He had no history of tuberculosis or exposure to any known infected individuals. He had been living in the United States for 4 years and was working at a bakery.

The patient’s triage vital signs were as follows: heart rate 167 beats/min, blood pressure 105/67 mmHg, respiratory rate 30 breaths/min, temperature 38.2°C, and oxygen saturation 99% on room air. An ECG was obtained that showed atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response of 160 beats/min.

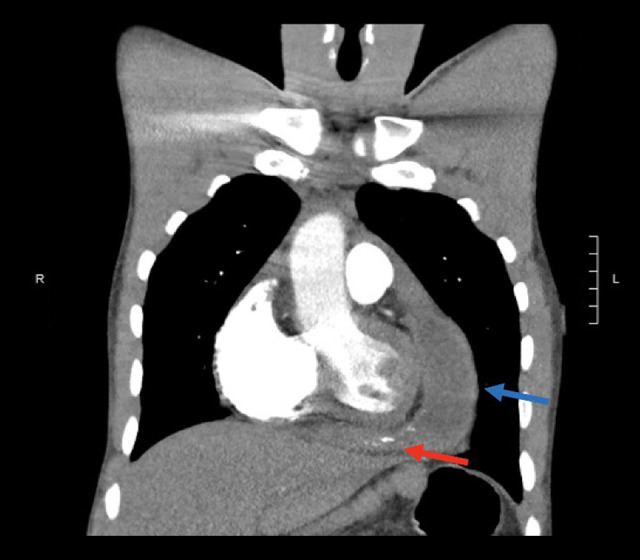

A chest X-ray revealed cardiomegaly with bibasilar edema concerning for congestive heart failure. D-dimer was elevated at 2120 ng/mL FEU. CTA of the chest showed extensive pericardial thickening with multifocal calcification, a complex pericardial fluid collection, and concern for regional tamponade of the right ventricle, all thought to be consistent with an infectious etiology (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Chest CTA during first hospital admission demonstrating a pericardial effusion (blue arrow) and irregular pericardial thickening with multifocal calcification (red arrow).

The patient was admitted to the cardiac surgery ICU for expected pericardial biopsy for definitive diagnosis of presumptive pericardial tuberculosis, and his clinical status improved with fluid resuscitation. An echocardiogram showed a large and complex pericardial effusion with echo-bright areas, thought to represent partial calcification and areas of dense organization. There was no evidence of tamponade. To evaluate for constrictive disease, he subsequently underwent cardiac catheterization, finding normal right and left heart filling pressures. There was no evidence of restriction or constriction physiology during the catheterization.

Multiple sputum samples were sent for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) smear and culture and nucleic acid amplification test (Xpert MTB/RIF) testing, and all were negative. Blood cultures were negative. The fourth-generation HIV test was negative. Procalcitonin was not measured. Atrial fibrillation resolved after fluid resuscitation, and he did not have further indication for anticoagulation. The patient was started on rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, ethambutol (RIPE), and prednisone empirically pending pericardial biopsy. After beginning this treatment, the clinicians felt that biopsy was not necessary due to the patient’s risk factors and the high clinical suspicion for tuberculous pericarditis. He was discharged from the hospital on RIPE and prednisone with instructions to follow up with an infectious diseases specialist as an outpatient. He was symptomatically improved upon discharge, nine days after initial presentation.

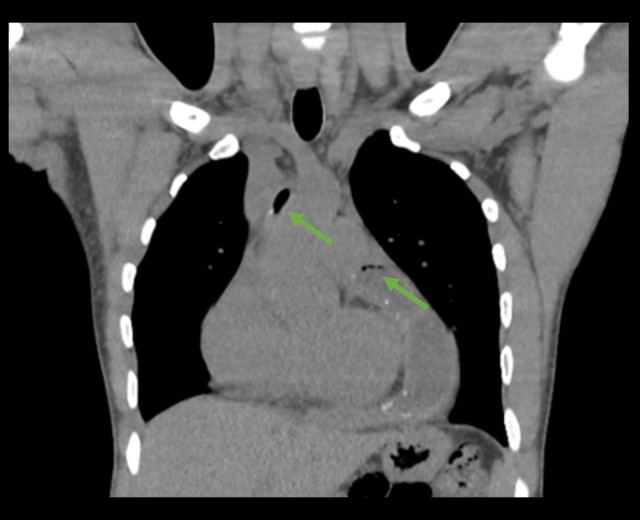

Eighteen days after initiation of treatment, he was evaluated in the outpatient setting and underwent another CT chest. Imaging was notable for multiple new locules of air within the pericardium (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Chest CT during outpatient evaluation demonstrating interval development of associated locules of air (green arrows).

Thirty-six days after treatment initiation, he presented to the hospital with fatigue, pleuritic chest pain, and shortness of breath. An echocardiogram was performed and demonstrated a stable pericardial effusion with a possible effusive/constrictive process. The chest pain resolved without intervention, and he was discharged home to continue RIPE and prednisone.

He was seen in the outpatient cardiology clinic a month and a half after his second hospitalization and stated he had no chest pain or difficulty breathing at that time. A repeat echo-cardiogram was recommended in three months.

Approximately three and a half months after his initial presentation, he again presented to the emergency department with acute onset of radiating, pleuritic chest pain. He reported adherence to his outpatient therapy.

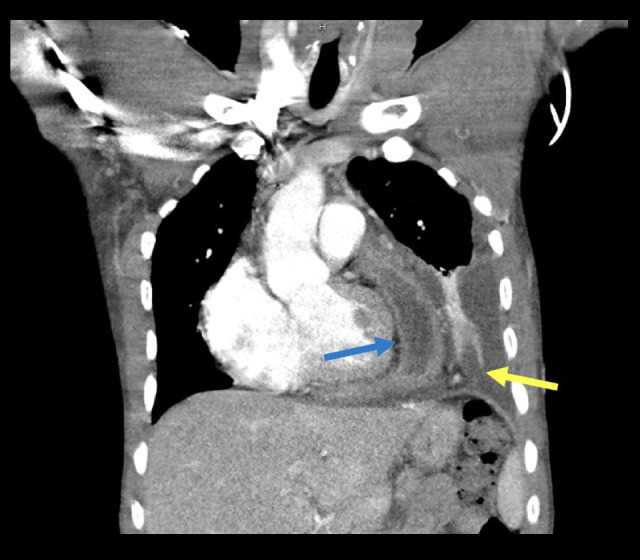

His vital signs were notable for a temperature of 37.9°C and tachycardia, and his oxygen saturation on room air was 100%. A chest X-ray revealed an enlarged cardiomediastinal silhouette and a new, moderate-sized left pleural effusion. A CT chest with intravenous contrast demonstrated a large left pleural effusion with underlying parenchymal consolidation, contra-lateral mediastinal shift, and a persistent complex pericardial fluid collection consisting of thickening, calcifications, and air bubbles (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Chest CT during third hospitalization demonstrating a complex pericardial fluid collection (blue arrow) and a large left pleural effusion with underlying parenchymal consolidation (yellow arrow).

He was empirically treated with a 5-day course of ceftriaxone and doxycycline for community-acquired pneumonia, while prednisone and anti-tuberculosis treatment were continued. A pigtail catheter was placed for drainage of the pleural effusion. The fluid was exudative by Light’s criteria; an AFB smear and Xpert MTB/RIF testing of the pleural fluid were negative. Adenosine deaminase level of the pleural fluid was within normal limits at 2.5 u/L. Sputum AFB smears and Xpert MTB/RIF tests were also negative. Rifampin and isoniazid levels were obtained and found to be within the therapeutic range. Blood cultures were negative.

As no definitive diagnosis had been made, and he had not improved after several weeks of anti-tuberculous therapy, rheumatology was consulted. However, the consulting team felt that his presentation was unlikely to be rheumatologic in nature as several markers, including antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide, and C3 levels, were all within normal limits. Despite continued drainage of his pleural space via the chest tube, he was intermittently febrile with an increasing leukocytosis. On day 10 of admission he underwent a left anterior thoracotomy and pericardial biopsy, and samples were taken of pleural fluid, pleura, and superficial pericardium. During the thoracotomy, dense adhesions were noted between the lung, pericardium, and pleura.

Histopathology of the surgical specimens revealed fibrinous pericarditis and purulent pleuritis with numerous gram-positive cocci in the pleural tissue. Tissue cultures were positive for Prevotella oris in the pleura tissue and fluid. 16s rRNA bacterial sequencing of intraoperative pleural and pericardial samples were positive for Prevotella oris. Next-generation sequencing of cell-free DNA (Karius™) from blood was positive for Prevotella oris and Fusobacterium nucleatum. A work-up for esophageal perforation and dental infection with a fluoroscopic esophagram and panoramic dental X-rays was unremarkable. He was started on ampicillin/sulbactam 3 g every 6 hours, causing significant improvement of his chest pain and shortness of breath, and he was discharged on amoxicillin/clavulanate

Upon completion of his antibiotic course, his pulmonary symptoms had completely resolved, and his fatigue was much improved. A follow-up chest X-ray showed reinflation of his left lung and resolution of his pleural effusion with minimal residual scarring. A repeat echocardiogram three months after treatment was normal, without pericardial effusion.

Discussion

Bacterial pericarditis has become an increasingly rare diagnosis since the advent of antibiotics. Most cases are due to pneumonia, endocarditis, or bacteremia. Prior to the widespread use of antibiotics, the most common organism was Streptococcus pneumoniae [5]. In the current antibiotic era, most cases of bacterial pericarditis are associated with a predisposing condition, such as chest surgery or trauma, an immunocompromised state, or malignancy [6]. The route of infection may be hematogenous, direct infection, contiguous spread from a thoracic source, or spread from a subdiaphragmatic focus of infection [7]. Although Staphylococcus aureus is currently the most common causative organism, there has also been a notable increase in the proportion of purulent pericarditis cases due to gram-negative and anaerobic organisms, possibly related to increased use of pneumococcal vaccines [2,5]. Regardless of the etiology, bacterial pericarditis is typically an acute illness and, if untreated, is almost uniformly fatal. Even with antibiotic treatment, mortality may be as high as 20–30% [5,7].

In patients with polyserositis who have traveled to endemic areas, tuberculosis is an important diagnostic consideration [8]. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where this patient was from, is included in the World Health Organization’s list of high tuberculosis burden countries. The 2019 incidence was estimated at 320/100 000 [9]. In endemic settings, such as the DRC, tuberculosis continues to be the most common cause of constrictive pericarditis [10]. The diagnosis of tuber-culous pericarditis is often made clinically; definitive diagnosis may be challenging due to the need for sampling of pericardial fluid or tissue and is often deferred [11]. Tuberculous pericarditis is often paucibacillary as AFB smears and cultures of pericardial fluid may be negative [12]. Xpert MTB/RIF has a reported sensitivity of 63.8–72.2% for the diagnosis of tuber-culous pericarditis [13,14].

The suspicion for tuberculous pericarditis in this patient was high because of his demographic risk factors and subacute clinical presentation. Pericardial biopsy was initially deferred due to the patient’s relative clinical stability and the belief that definitive diagnosis was not necessary. Even during his readmissions, RIPE and corticosteroids were continued despite lack of clinical improvement, as tuberculosis seemed the most likely etiology of his pericarditis. In retrospect, the presence of gas on repeat CT imaging could have suggested an alternate diagnosis, as the limited publications on pneumopericardium in the setting of tuberculosis pericarditis were usually attributed to iatrogenic causes [15–17]. It was not until pericardial and pleural tissue were obtained that the correct diagnosis was determined. This case emphasizes the important point that when diagnostic tools for pericarditis are available, it is imperative to pursue definitive diagnosis to ensure the correct identification of the pathogen and to avoid potential adverse effects from prolonged unnecessary therapy [18]. Additionally, delay in diagnosis and treatment can lead to progression of disease, as seen in this patient.

In this patient, it is unclear whether the corticosteroids provided some anti-inflammatory benefit and delayed disease progression or exacerbated the infection, leading to his subsequent hospitalizations with chest pain, empyema, and worsening pericardial effusion.

Our patient’s bacterial pericarditis and empyema were ultimately presumed to be due to hematogenous spread from a sub-clinical oropharyngeal infection. Although he did not have any clear risk factors for bacterial translocation, such as odontogenic infection, known bacteremia, or esophageal perforation, he did later report having a sore throat prior to development of his other symptoms. This history, along with the eventual identification of oral microbes, suggests a possible oropharyngeal infection, such as Group A Streptococcus [19]. This infection could have resulted in an inflammatory process, leading to poly-microbial translocation of oral flora and subsequent hematogenous spread to the pericardium and pleural space. Prevotella and Fusobacterium, known oral flora, have in rare instances both been reported to cause bacterial pericarditis [20–22].

Conclusions

When treating patients from a tuberculosis-endemic region, it is important not to anchor on this diagnosis when evaluating a potential infection. Our case of polymicrobial pericarditis that was initially assumed to be tuberculosis pericarditis demonstrates the importance of actively pursuing a definitive tissue diagnosis when feasible. In this manner, appropriate therapy is administered and potential adverse effects of unnecessary treatment are avoided.

Footnotes

Declaration of Figures’ Authenticity

All figures submitted have been created by the authors who confirm that the images are original with no duplication and have not been previously published in whole or in part.

References:

- 1.Imazio M, Gaita F, LeWinter M. Evaluation and treatment of pericarditis: A systematic review [published erratum appears in JAMA 2015;314(18): 1978; published erratum appears in JAMA 2016;315(1): 90] JAMA. 2015;314(14):1498–506. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parikh SV, Memon N, Echols M, et al. Report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2009;88(1):52–65. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e318194432b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zayas R, Anguita M, Torres F, et al. Incidence of specific etiology and role of methods for specific etiologic diagnosis of primary acute pericarditis. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75(5):378–82. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80558-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pankuweit S, Ristić AD, Seferović PM, Maisch B. Bacterial pericarditis: Diagnosis and management. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2005;5(2):103–12. doi: 10.2165/00129784-200505020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klacsmann PG, Bulkley BH, Hutchins GM. The changed spectrum of purulent pericarditis: An 86 year autopsy experience in 200 patients. Am J Med. 1977;63(5):666–73. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(77)90150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubin RH, Moellering RC. Clinical, microbiologic and therapeutic aspects of purulent pericarditis. Am J Med. 1975;59(1):68–78. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(75)90323-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sagristà-Sauleda J, Barrabés JA, Permanyer-Miralda G, Soler-Soler J. Purulent pericarditis: Review of a 20-year experience in a general hospital. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22(6):1661–65. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90592-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golden MP, Vikram HR. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis: An overview. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72(9):1761–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Global tuberculosis report 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/336069/9789240013131-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khalid N, Ahmad SA, Shlofmitz E. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; Feb 6, 2021. Pericardial calcification. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trautner BW, Darouiche RO. Tuberculous pericarditis: Optimal diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(7):954–61. doi: 10.1086/322621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reuter H, Burgess L, van Vuuren W, Doubell A. Diagnosing tuberculous pericarditis. QJM. 2006;99(12):827–39. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcl123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saeed M, Ahmad M, Iram S, et al. GeneXpert technology. A breakthrough for the diagnosis of tuberculous pericarditis and pleuritis in less than 2 hours. Saudi Med J. 2017;38(7):699–705. doi: 10.15537/smj.2017.7.17694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pandie S, Peter JG, Kerbelker ZS, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of quantitative PCR (Xpert MTB/RIF) for tuberculous pericarditis compared to adenosine deaminase and unstimulated interferon-γ in a high burden setting: A prospective study. BMC Med. 2014;12:101. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ciobanu P, Donoiu I, Militaru C, et al. Pneumopericardium in a young patient with tuberculous pericarditis. CorSalud. 2018;10(1):78–79. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abrahan Iv LL, Obillos SMO, Aherrera JAM, et al. A rare case of pneumopericardium in the setting of tuberculous constrictive pericarditis. Case Rep Cardiol. 2017;2017:4257452. doi: 10.1155/2017/4257452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi WH, Hwang YM, Park MY, et al. Pneumopericardium as a complication of pericardiocentesis. Korean Circ J. 2011;41(5):280–82. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2011.41.5.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayosi BM, Burgess LJ, Doubell AF. Tuberculous pericarditis. Circulation. 2005;112(23):3608–16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.543066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhaduri-McIntosh S, Prasad M, Moltedo J, Vázquez M. Purulent pericarditis caused by group a streptococcus. Tex Heart Inst J. 2006;33(4):519–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chattopadhyay I, Verma M, Panda M. Role of oral microbiome signatures in diagnosis and prognosis of oral cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2019;18:1533033819867354. doi: 10.1177/1533033819867354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanwal A, Avgeropoulos D, Kaplan JG, Saini A. Idiopathic purulent pericarditis: A rare diagnosis. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21:e921633. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.921633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhattarai M, Yost G, Good CW, et al. A case report and literature review. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;47(2):155–59. doi: 10.5090/kjtcs.2014.47.2.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]