Abstract

Recent studies have reported that immune checkpoint inhibitors are effective against various defective mismatch repair (dMMR)/microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) cancers. A limited number of reports are available on the frequency of dMMR/MSI-H carcinoma in biliary tract cancer (BTC), describing its clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis. The latter carcinoma is also associated with Lynch syndrome (LS). The present study was performed to investigate the frequency of patients with dMMR/MSI-H in BTC and the clinical characteristics of BTC with dMMR/MSI-H in a single institution in Japan. A total of 116 patients with BTC who underwent curative surgical resection at Kagawa University Hospital between January 2008 and December 2017 were included. The protein expression levels of the mismatch repair (MMR) genes [mutL homolog 1 (MLH1), mismatch repair endonuclease PMS2 (PMS2), MutS homolog (MSH)2 and MSH6] were assessed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue specimens. Subsequently, MSI testing was performed on patients who exhibited loss of MMR protein expression. Loss of expression of one or more proteins was detected in five cases (4.3%). Loss of MLH1/PMS2 expression was observed in one case of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, whereas loss of PMS2 expression was noted in one case of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Loss of MSH2/MSH6 and MSH6 expression was noted in two cases of distal cholangiocarcinoma and loss of PMS2 expression in one case of ampullary carcinoma. Out of the five patients, two demonstrated MSI-H. Microsatellite stability was observed in two cases and for one case, no data were available. Two MSI-H cases were patients with loss of expression of MLH1/PMS2 and MSH2/MSH6. None of the five patients exhibited a past medical history or family history of suspected LS. The frequency of dMMR in BTC was ~5%, which was similar to that reported by similar studies performed in other countries. In the present study, IHC appeared to be more useful than MSI testing for detecting MMR abnormalities with regards to the detection rate. Furthermore, there may only be a limited number of patients with BTCs who are likely to benefit from the therapeutic effects of treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Keywords: biliary tract cancer, defective mismatch repair, microsatellite instability-high, immunohistochemistry, Lynch syndrome

Introduction

Malignant tumors derived from the biliary tract exhibit a variety of clinicopathological characteristics. These characteristics may be considered as epidemiological risk factors and may affect the diversity of the genetic architecture and the tissue microenvironment (1). Defective mismatch repair (dMMR) tumors are caused by loss of function of MMR proteins due to genetic (2) or epigenetic (3) events. This pathogenic variant in the germline of MMR genes [mutL homolog 1 (MLH1), MutS homolog (MSH)2, MSH6 and mismatch repair endonuclease PMS2 (PMS2)] is known to be the cause of Lynch syndrome (LS), a hereditary disease with a high incidence of colorectal and endometrial cancers. Numerous studies have reported on the expression of MMR proteins and on the incidence of microsatellite instability (MSI) status in biliary tract cancer (BTC), which is considered an LS-associated tumor (4–18). The approximate frequency of MSI-high (MSI-H) BTC is 5% for gallbladder carcinoma (GBCA), perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (pCCA) and distal CCA (dCCA), whereas it is estimated to be 10% for intrahepatic CCA (iCCA) and ampullary carcinoma (ampCA) (15).

In general, the treatment of BTC requires extended surgery, such as hepatectomy or pancreaticoduodenectomy, but the disease may be unresectable, depending on the patient's condition. Furthermore, BTC has poor prognosis due to the limited availability of effective chemotherapy options (19–22). Previous studies performed in recent years have reported that the immune checkpoint inhibitor anti-programmed death-1 (PD-1) antibody has a high response rate in patients with MSI-H. The latter is a genetic characteristic of certain solid tumors, is caused by dMMR and contributes to the overall survival of these patients (7,23,24). It has been previously reported that certain cases of MSI-H BTC may be successfully treated with pembrolizumab (25,26). Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate MMR protein expression and/or the MSI status in tumors in order to select patients who may be expected to benefit from treatment with anti-PD-1 antibodies.

In the case of colorectal (27) and endometrial (28) cancers, the concordance rate between immunohistochemistry (IHC) and MSI results is >90%, whereas such comparisons have not yet been made in patients with BTC. IHC is cost-effective and widely available in several facilities compared with MSI testing. Furthermore, IHC may be performed to determine the expression levels of the MMR genes that are likely to exhibit genetic/epigenetic changes (29,30).

The present study was performed to investigate the frequency of dMMR tumors and the clinical factors in dMMR cases using IHC. The aim was to determine the extent to which dMMR/MSI-H cases may be detected in BTCs resected at a single institution in Japan.

Patients and methods

Patients

The present study retrospectively enrolled patients who were diagnosed with BTC and underwent surgery between January 2008 and December 2017 at Kagawa University Hospital (Kagawa, Japan). A total of 116 patients were included in the present study. A total of 73 (62.9%) males and 43 (37.1%) females participated in the study. The demographic and clinicopathological data and the personal/family history of the patients were obtained from medical charts. Pathological tumor-node-metastasis staging was performed using the international system for BTC staging adopted by the American Joint Committee on Cancer and the Union for International Cancer Control, 8th edition (31). Table I presents the clinicopathological characteristics. The entire series consisted of iCCA (n=14, 12.1%), pCCA (n=17, 14.6%), dCCA (n=32, 27.6%), GBCA (n=30, 25.9%) and ampCA (n=23, 19.8%). The median age at diagnosis was 73 years (range, 38–93 years) and the majority of the included patients were aged ≥70 years (n=76; 65.5%).

Table I.

Clinicopathological characteristics of the patient cohort.

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 73 (62.9) |

| Female | 43 (37.1) |

| Age at diagnosis, years | 73 (38–93) |

| <70 | 40 (34.5) |

| ≥70 | 76 (65.5) |

| Localization | |

| iCCA | 14 (12.1) |

| pCCA | 17 (14.6) |

| dCCA | 32 (27.6) |

| GBCA | 30 (25.9) |

| ampCA | 23 (19.8) |

| History of LS-associated diseases | |

| Yes | 18 (15.5) |

| No | 98 (84.5) |

| Family history of LS-associated diseases | |

| Yes | 8 (6.9) |

| No | 108 (93.1) |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen, ng/mla | 2.6 (0.8–35) |

| Normal | 96 (84.2) |

| Abnormal | 18 (15.8) |

| Carbohydrate antigen 19-9, U/mla | 32.5 (2–63143) |

| Normal | 61 (53.5) |

| Abnormal | 53 (46.5) |

| Main differentiation | |

| Papillary | 20 (17.3) |

| Well | 48 (41.4) |

| Moderate | 31 (26.7) |

| Poor | 10 (8.6) |

| Adenosquamous | 7 (6) |

| Lymph node metastasis | |

| 0 | 73 (62.9) |

| 1 | 43 (37.1) |

| Resection margin | |

| 0 | 104 (89.7) |

| 1 | 12 (10.3) |

| UICC stage | |

| 1 | 31 (27) |

| 2 | 48 (41.7) |

| 3 | 30 (26.1) |

| 4 | 6 (5.2) |

| Invasion into lymphatic vessels | |

| 0 | 38 (36.5) |

| 1 | 66 (63.5) |

| Invasion into veins | |

| 0 | 42 (36.8) |

| 1 | 72 (63.2) |

| 0 | 47 (45.6) |

| 1 | 56 (54.4) |

Values are expressed as n (%) or the median (range).

The normal reference ranges of carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 are 0-5 U/ml and 0-37 ng/ml, respectively. LS, Lynch syndrome; UICC, Union for International Cancer Control; CCA, cholangiocarcinoma; iCCA, intrahepatic CCA; pCCA, perihilar CCA; dCCA, distal CCA; GBCA, gallbladder carcinoma; ampCA, ampullary carcinoma.

IHC analysis for MMR protein detection

IHC was performed in order to assess the expression levels of four MMR proteins (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2) using a VENTANA MMR IHC Panel (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.; Roche Diagnostics), according to the manufacturer's protocol. The samples were prepared from 4-µm formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections. The following primary antibodies were used for the detection of human (h) MMR proteins: Anti-hMLH1 antibody [cat. no. 518-114336; anti-MLH1 (M1) mouse monoclonal primary antibody], anti-hMSH2 antibody (cat. no. G219-1129; anti-MSH2 mouse monoclonal primary antibody), anti-hMSH6 antibody (cat. no. SP93; anti-MSH6 rabbit monoclonal primary antibody) and anti-hPMS2 antibody (cat. no. A16-4; anti-PMS2 mouse monoclonal primary antibody); all ready-to-use from Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.; Roche Diagnostics. The normal staining patterns for MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2 were nuclear. The absence of nuclear staining in the tumor cells in the presence of nuclear staining of non-neoplastic cells, such as normal epithelial cells, lymphocytes and stromal cells, was considered to represent an abnormal pattern (29). The staining results were evaluated by consensus between two independent pathologists and surgeons, who were blinded to the clinical status of each patient.

DNA extraction

DNA was extracted from 4-µm FFPE sections of cancer tissues using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen GmbH).

MSI testing

MSI testing was performed in patients with dMMR and in 8 patients with a family history of LS-associated cancers. MSI testing was performed using the MSI analysis system, version 1.2 (Promega Corporation), which evaluates the MSI status of the following five mononucleotide microsatellite markers: BAT25, BAT26, NR21, MONO-27 and NR24 (32). Following amplification of the marker genes, the products were subjected to fragment analysis using the Applied Biosystems 3500 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and GeneMapper software version 4.1 (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). When two or more markers demonstrated altered numbers of repeats, the MSI status of the tumor was classified as MSI-H.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are reported as the median (range) for continuous variables and as frequency (%) for categorical variables. The overall survival was calculated as the time from surgery to the date of death (event) or the last follow-up date (censored) using the Kaplan-Meier method. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro version 14 (SAS Institute Inc.).

Results

IHC analysis

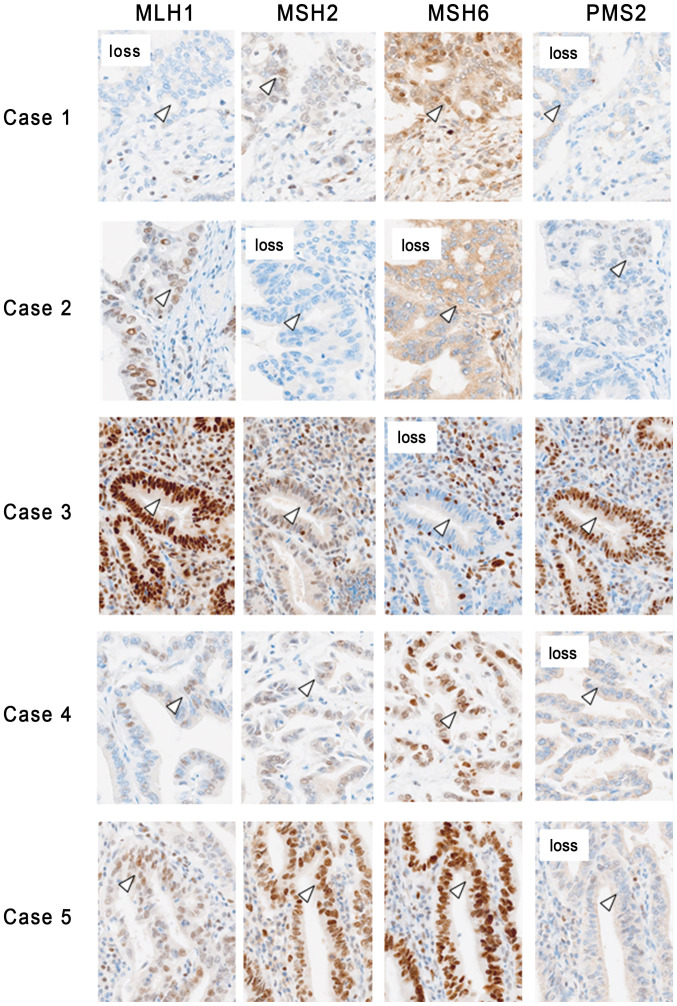

A total of 5 out of the 116 patients with BTC (4.3%) exhibited loss of expression of one or more proteins. Loss of MMR protein expression was observed for MLH1/PMS2 in one case of iCCA, for PMS2 in one case of pCCA, for MSH2/MSH6 and MSH6 in two cases of dCCA and for PMS2 in one case of ampCA (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Expression pattern of MMR proteins in tissues from patients with biliary tract cancer and defective MMR. In case 1, loss of MLH1 and PMS2 was observed in the nuclei of cancer cells, while loss of MSH2 and MSH6 was observed in case 2. In case 3, loss of MSH6 was observed in the nuclear region of the cancer cells, while loss of PMS2 was observed in cases 4 and 5. The arrowheads indicate cancer cells (magnification, ×200). MMR, mismatch repair; MLH1, mutL homolog 1; PMS2, mismatch repair endonuclease PMS2; MSH, MutS homolog.

MSI assessment and clinicopathological and molecular characteristics of dMMR cases

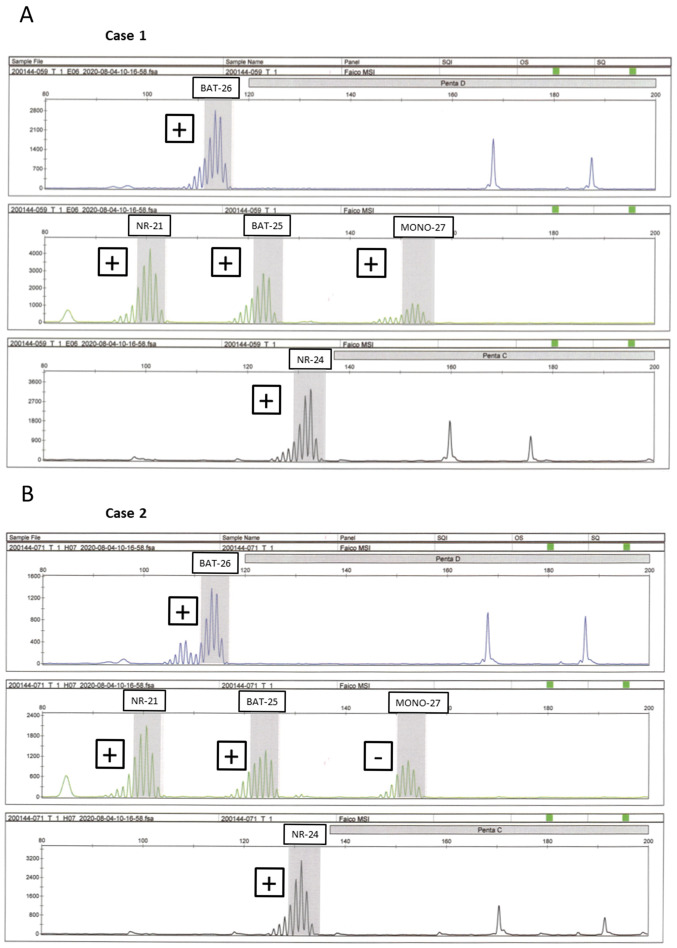

MSI assessment was performed on five patients with dMMR as determined by IHC. A total of two patients (1.7%) exhibited MSI-H, with loss of MLH1/PMS2 (iCCA) loss of MSH2/MSH6 (dCCA) expression was noted in each of these two patients (Fig. 2). In one case with the loss of MSH6 (dCCA) expression, it was not possible to measure DNA amplification owing to suspected DNA degradation, whereas in two cases with the loss of PMS2 (pCCA) and PMS2 (ampCA) expression, MSI testing exhibited microsatellite stability (MSS). Table II indicates the clinicopathological characteristics of these patients with dMMR BTC. The patient age range was 55–93 years, with 3 (60%) males and 2 (40%) females, and none of the 5 patients had any history of cancer or family history of LS-associated disease. None of the patients survived; two succumbed to the original disease due to recurrence and the remaining three did not survive due to the presence of other conditions. Among 8 patients with a family history of LS-associated cancers, all cases exhibited both proficient MMR and MSS.

Figure 2.

Representative electropherograms of the cancer tissues exhibiting MSI-H. The presence of MSI for (A) case 1 and (B) case 2 is indicated. MSI-H is present when the maximal peak at each marker is situated outside the quasi-monomorphic variation range (gray zone). In cases 1 and 2, different-sized peaks were observed other than a distinctive peak from an allele (plus). Different-sized peaks were described as ‘positive’ and the results that did not yield peaks as ‘negative’. Five mononucleotide microsatellite markers: BAT25, BAT26, NR21, MONO-27 and NR24. MSI-H, MSI-high; MSI, microsatellite instability.

Table II.

Clinicopathological and molecular characteristics of five cases of defective mismatch repair in biliary cancer.

| Item | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 55 | 93 | 60 | 62 | 76 |

| Sex | Male | Female | Female | Male | Male |

| Location | iCCA | dCCA | dCCA | pCCA | ampCA |

| Previous history of cancer | None | None | None | None | None |

| Family history | None | None | None | None | None |

| Immunohistochemistry | dMLH1/PMS2 | dMSH2/MSH6 | dMSH6 | dPMS2 | dPMS2 |

| MSS status | MSI-H | MSI-H | Unmeasurable | MSS | MSS |

| BAT-25 | + | + | − | − | |

| BAT-26 | + | + | − | − | |

| NR-21 | + | + | − | − | |

| MONO-27 | + | − | − | − | |

| NR-24 | + | + | − | − | |

| Main differentiation | Well | Moderate | Poor | Well | Moderate |

| UICC stage | 2 | 3A | 1 | 3C | 3A |

| Resection margin | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Recurrence (location) | + (Lymph node) | − | − | + (Pulmonary) | − |

| Overall survival, months | 17 | 6 | 48 | 37 | 34 |

| Circumstance of death | DOD | DID | DID | DOD | DID |

UICC, Union for International Cancer Control; CCA, cholangiocarcinoma; iCCA, intrahepatic CCA; pCCA, perihilar CCA; dCCA, distal CCA; ampCA, ampullary carcinoma; d, defective; MLH1, mutL homolog 1; PMS2, mismatch repair endonuclease PMS2; MSH, MutS homolog; MSI-H, microsatellite instability-high; MSS, microsatellite stability; DOD, died of disease; DID, died with intercurrent disease.

Discussion

The present study was performed at a single institution in Japan. The frequency of dMMR in BTC was 4.3% and that of MSI-H in BTC was 1.7%. In addition to the commonly performed evaluation of dMMR, which includes IHC analysis, MSI assessment was performed. In a case series of BTC, a small number of dMMR/MSI-H BTC was reported. Previous studies have reported that the prevalence of dMMR in BTCs is 0–9.4% (4,10,12,14,18). A large study, which used next-generation sequencing, reported a frequency of ~2% in BTCs (7). Previous studies that investigated the prevalence of MSI-H BTCs reported a frequency of 0–18% (5,6,8–14). Silva et al (15) reported that MSI-H accounted for ~5% of GBCA and extrahepatic CCA and for ~10% of iCCA and ampCA. Comparison of previous studies performed in Asia and Japan (6,8–11,16,33) with those from Western countries (4,5,12–14,34) indicated that the incidence of BTC with dMMR/MSI-H was almost the same in both Asian and Western countries (3.1 and 4.4%, respectively). Of note, the results of the present study were observed to be similar to those of the previous reports. However, while there were no MSI cases among patients with GBCA in the present cohort study, the frequency of dMMR/MSI-H cases in GBCA was ~5% in previous reports (15). In previous studies from Japan, Yoshida et al (35) determined a frequency of 0% (0/30), Yanagisawa et al (36) detected 6% (1/17), Nagahashi et al (37) reported 42% (8/19) and Akagi et al (33) 1.5% (3/200). The incidence of GBCA with dMMR/MSI-H was inconsistent even in Japan. The result of the present study showing that no MSI cases were observed in GBCA may be due to differences in population.

Several studies have reported concordant and discordant findings regarding the prevalence of dMMR and MSI-H in BTC. Previous studies on colorectal cancer have reported that IHC is also useful for the detection of dMMR with a sensitivity of 92% and for preventing MSI with a specificity of 99% (38–40). These results are different from those reported in the present study. Of the five cases with loss of MMR protein expression, two exhibited MSI-H. The prevalence of MSI-H BTC was lower than that of the dMMR tumors and discordant results were observed between IHC and PCR-based techniques. One case of MSH6 was reported in the current study, which was dMMR as assessed by IHC, but unmeasurable according to MSI testing. The resection specimen of this case was a paraffin-embedded section of an old specimen collected 9 years previously and therefore, it was hypothesized that the IHC staining result may have been compromised due to damage caused to the fixed tissue. The other two cases were deficient in PMS2 and the sensitivities of the MSI and IHC tests for detection of PMS2 mutations were 67 and 75%, respectively; thus, MSI testing was comparatively less sensitive (41,42). As mentioned earlier, inconsistencies have been reported in the results obtained between the two aforementioned methods (IHC and MSI testing). Therefore, these methods should be considered complementary. Specific differences in sensitivity have been reported depending on the mutated pathogenic gene. Therefore, it is considered that the therapeutic effect of anti-PD-1 antibodies may be expected if either dMMR or MSI-H is recognized.

In the present study, dMMR/MSI-H was observed in one case of MLH1/PMS2 and in one case of MSH2/MSH6. In general, the MLH1/PMS2 expression pattern suggested hypermethylation of MLH1 (43). It is considered that methylation is the cause of loss of MLH1 expression, which is observed in colorectal and uterine cancers, whereas loss of MSH2 expression may be due to somatic mutations in both alleles in addition to methylation. Tajima et al (44) reported that somatic mutations were also detected in both of these alleles in uterine carcinoma. In the present study, the five patients with loss of MMR protein expression did not survive and it was therefore impossible to perform an additional detailed genetic analysis. However, it was hypothesized that methylation and somatic alterations may have been associated with loss of MLH1 or MSH2 expression in the cases with dMMR/MSH-H, since these patients did not have any past history or family history of cancer. A study from Thailand (45) reported that CCA derived from liver fluke infection had a high incidence of MSI-H (9/13 cases, 69%). Although the pathogenesis of BTC in Japan is expected to be different from that in Thailand, the study will contribute to identify the mechanisms of alteration to MSI-H, leading to an increased understanding of the development of BTC.

BTC is also known as one of the important LS-associated tumors, as described in the revised Bethesda guidelines (46). Patients with colon and uterine cancers, which have a high frequency of dMMR/MSI-H, may be screened for the incidence of LS. In colon cancer, LS is diagnosed in ~3% of sporadic cases (47,48). Although eight patients had a family history of LS-associated cancers, they exhibited both proficient MMR and MSS. In the present study, none of the BTC patients with dMMR had a past medical history or family history of LS-associated cancers. Therefore, universal screening for all patients with newly diagnosed BTC may be an effective screening method, similar to that used for colorectal and uterine cancers.

A relatively large proportion of patients with BTC are diagnosed as unresectable (49) and even those who undergo curative resection have a high recurrence rate (50,51). A comparable treatment regimen to gemcitabine or cisplatin is yet to be established. The 5-year survival rate is 5–15% for all patients with BTC (19–21). In recent years, anti-PD-1 antibodies and immune checkpoint inhibitors have been reported to be effective in the treatment of various types of MSI-H solid tumors (23,52). It is expected for this therapeutic approach to improve the overall survival of patients with non-colorectal cancer who exhibit loss of MMR protein expression and/or MSI-H (53,54). Therefore, evaluation of MMR protein expression and/or MSI may be necessary to select patients with cancer who may benefit from treatment with anti-PD-1 antibodies. In the present study, the incidence of BTC with dMMR/MSI-H was ~5%, which is in agreement with that reported in previous studies (4,10,12,14,18). Based on these findings, it is suggested that screening should be routinely performed, since the prognosis of patients with BTC and dMMR/MSI-H was considerably poor.

There were certain limitations to the present study. First, it was performed at a single institution in the area of Shikoku, Japan. Therefore, the possibility of a regional selection bias among patients with BTC should be considered. Furthermore, all five patients with loss of MMR protein expression had already succumbed to the disease and it was not possible to perform any detailed genetic analysis on them. Finally, the difference between patients with pMMR and dMMR was not analyzed due to the low number of dMMR cases. In the future, additional data from other institutions must be collected in order to determine the exact prevalence of dMMR among patients with BTC.

The present study was a comprehensive study performed to examine the incidence of dMMR BTC in a hospital-based population in Japan. The data revealed a relatively low prevalence of dMMR cases. In the present study, IHC was indicated to be more useful than MSI testing for detecting MMR abnormalities with regards to the detection rate. Consequently, selected patients with BTC may benefit from the therapeutic effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- dMMR

defective mismatch repair

- MSI

microsatellite instability

- LS

Lynch syndrome

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- UICC

Union for International Cancer Control

- CCA

cholangiocarcinoma

- iCCA

intrahepatic CCA

- pCCA

perihilar CCA

- dCCA

distal CCA

- GBCA

gallbladder carcinoma

- ampCA

ampullary carcinoma

- PD-1

programmed death-1

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

YA devised and designed the study. YA and KK analyzed and interpreted the patient data regarding biliary tract disease. HKa, AM, HKo and TsM contributed by providing medical preoperative diagnoses. RI, ToM and RH performed IHC and histopathological evaluations. KK, YS and KO were involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. YA, KK, HM, HS, MO, YS and KO designed the treatment plan and performed the surgeries. KK and KO confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the Committee of Kagawa University (approval no. 2019-231). It conformed to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from the subjects in the form of an informative or disclosure document.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Wardell CP, Fujita M, Yamada T, Simbolo M, Fassan M, Karlic R, Polak P, Kim J, Hatanaka Y, Maejima K, et al. Genomic characterization of biliary tract cancers identifies driver genes and predisposing mutations. J Hepatol. 2018;68:959–969. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peltomäki P. Update on Lynch syndrome genomics. Fam Cancer. 2016;15:385–393. doi: 10.1007/s10689-016-9882-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pal T, Permuth-Wey J, Sellers TA. A review of the clinical relevance of mismatch-repair deficiency in ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:733–742. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agaram NP, Shia J, Tang LH, Klimstra DS. DNA mismatch repair deficiency in ampullary carcinoma: A morphologic and immunohistochemical study of 54 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;133:772–780. doi: 10.1309/AJCPGDDE8PLLDRCC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonneville R, Krook MA, Kautto EA, Miya J, Wing MR, Chen HZ, Reeser JW, Yu L, Roychowdhury S. Landscape of Microsatellite Instability Across 39 Cancer Types. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017;2017:1–15. doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isa T, Tomita S, Nakachi A, Miyazato H, Shimoji H, Kusano T, Muto Y, Furukawa M. Analysis of microsatellite instability, K-ras gene mutation and p53 protein overexpression in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:604–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Aulakh LK, Lu S, Kemberling H, Wilt C, Luber BS, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. 2017;357:409–413. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu D, Momoi H, Li L, Ishikawa Y, Fukumoto M. Microsatellite instability in thorotrast-induced human intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2002;102:366–371. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Momoi H, Itoh T, Nozaki Y, Arima Y, Okabe H, Satoh S, Toda Y, Sakai E, Nakagawara K, Flemming P, et al. Microsatellite instability and alternative genetic pathway in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2001;35:235–244. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(01)00106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park S, Kim SW, Kim SH, Darwish NS, Kim WH. Lack of microsatellite instability in neoplasms of ampulla of Vater. Pathol Int. 2003;53:667–670. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2003.01534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rashid A, Ueki T, Gao YT, Houlihan PS, Wallace C, Wang BS, Shen MC, Deng J, Hsing AW. K-ras mutation, p53 overexpression, and microsatellite instability in biliary tract cancers: A population-based study in China. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3156–3163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruemmele P, Dietmaier W, Terracciano L, Tornillo L, Bataille F, Kaiser A, Wuensch PH, Heinmoeller E, Homayounfar K, Luettges J, et al. Histopathologic features and microsatellite instability of cancers of the papilla of vater and their precursor lesions. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:691–704. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181983ef7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salem ME, Puccini A, Grothey A, Raghavan D, Goldberg RM, Xiu J, Korn WM, Weinberg BA, Hwang JJ, Shields AF, et al. Landscape of Tumor Mutation Load, Mismatch Repair Deficiency, and PD-L1 Expression in a Large Patient Cohort of Gastrointestinal Cancers. Mol Cancer Res. 2018;16:805–812. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-17-0735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sessa F, Furlan D, Zampatti C, Carnevali I, Franzi F, Capella C. Prognostic factors for ampullary adenocarcinomas: Tumor stage, tumor histology, tumor location, immunohistochemistry and microsatellite instability. Virchows Arch. 2007;451:649–657. doi: 10.1007/s00428-007-0444-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silva VW, Askan G, Daniel TD, Lowery M, Klimstra DS, Abou-Alfa GK, Shia J. Biliary carcinomas: Pathology and the role of DNA mismatch repair deficiency. Chin Clin Oncol. 2016;5:62. doi: 10.21037/cco.2016.10.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suto T, Habano W, Sugai T, Uesugi N, Kanno S, Saito K, Nakamura S. Infrequent microsatellite instability in biliary tract cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2001;76:121–126. doi: 10.1002/1096-9098(200102)76:2<121::AID-JSO1022>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ueno M, Chung HC, Nagrial A, Marabelle A, Kelley RK, Xu L, Mahoney J, Pruitt SK, Oh DY. Pembrolizumab for advanced biliary adenocarcinoma: Results from the multicohort, phase II KEYNOTE-158 study. Ann Oncol. 2018;29((Suppl 8)):viii210. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy282.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winkelmann R, Schneider M, Hartmann S, Schnitzbauer AA, Zeuzem S, Peveling-Oberhag J, Hansmann ML, Walter D. Microsatellite Instability Occurs Rarely in Patients with Cholangiocarcinoma: A Retrospective Study from a German Tertiary Care Hospital. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:1421. doi: 10.3390/ijms19051421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson C, Kim R. Adjuvant therapy for resected extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: A review of the literature and future directions. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:322–327. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandi G, Farioli A, Astolfi A, Biasco G, Tavolari S. Genetic heterogeneity in cholangiocarcinoma: A major challenge for targeted therapies. Oncotarget. 2015;6:14744–14753. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeOliveira ML, Cunningham SC, Cameron JL, Kamangar F, Winter JM, Lillemoe KD, Choti MA, Yeo CJ, Schulick RD. Cholangiocarcinoma: Thirty-one-year experience with 564 patients at a single institution. Ann Surg. 2007;245:755–762. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000251366.62632.d3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, Madhusudan S, Iveson T, Hughes S, Pereira SP, et al. ABC-02 Trial Investigators Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1273–1281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marabelle A, Le DT, Ascierto PA, Di Giacomo AM, De Jesus-Acosta A, Delord JP, Geva R, Gottfried M, Penel N, Hansen AR, et al. Efficacy of pembrolizumab in patients with noncolorectal high microsatellite instability/mismatch repair-deficient cancer: results from the phase II KEYNOTE-158 study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1–10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.4_suppl.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zayac A, Almhanna K. Hepatobiliary cancers and immunotherapy: Where are we now and where are we heading? Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:8. doi: 10.21037/tgh.2019.09.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Czink E, Kloor M, Goeppert B, Fröhling S, Uhrig S, Weber TF, Meinel J, Sutter C, Weiss KH, Schirmacher P, et al. Successful immune checkpoint blockade in a patient with advanced stage microsatellite-unstable biliary tract cancer. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2017;3:a001974. doi: 10.1101/mcs.a001974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naganuma A, Sakuda T, Murakami T, Aihara K, Watanuki Y, Suzuki Y, Shibasaki E, Masuda T, Uehara S, Yasuoka H, et al. Microsatellite Instability-high Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma with Portal Vein Tumor Thrombosis Successfully Treated with Pembrolizumab. Intern Med. 2020;59:2261–2267. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.4588-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindor NM, Burgart LJ, Leontovich O, Goldberg RM, Cunningham JM, Sargent DJ, Walsh-Vockley C, Petersen GM, Walsh MD, Leggett BA, et al. Immunohistochemistry versus microsatellite instability testing in phenotyping colorectal tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1043–1048. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.4.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mills AM, Longacre TA. Lynch Syndrome: Female Genital Tract Cancer Diagnosis and Screening. Surg Pathol Clin. 2016;9:201–214. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaves P, Cruz C, Lage P, Claro I, Cravo M, Leitão CN, Soares J. Immunohistochemical detection of mismatch repair gene proteins as a useful tool for the identification of colorectal carcinoma with the mutator phenotype. J Pathol. 2000;191:355–360. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::AID-PATH644>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shia J, Tang LH, Vakiani E, Guillem JG, Stadler ZK, Soslow RA, Katabi N, Weiser MR, Paty PB, Temple LK, et al. Immunohistochemistry as first-line screening for detecting colorectal cancer patients at risk for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome: A 2-antibody panel may be as predictive as a 4-antibody panel. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1639–1645. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181b15aa2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brierley JD, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C, editors. Wiley-Blackwell; 2016. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, 8th Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bando H, Okamoto W, Fukui T, Yamanaka T, Akagi K, Yoshino T. Utility of the quasi-monomorphic variation range in unresectable metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:3411–3415. doi: 10.1111/cas.13774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akagi K, Oki E, Taniguchi H, Nakatani K, Aoki D, Kuwata T, Yoshino T. The real-world data on microsatellite instability status in various unresectable or metastatic solid tumors. Cancer Sci. 2021;112:1105–1113. doi: 10.1111/cas.14798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moy AP, Shahid M, Ferrone CR, Borger DR, Zhu AX, Ting D, Deshpande V. Microsatellite instability in gallbladder carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2015;466:393–402. doi: 10.1007/s00428-015-1720-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshida T, Sugai T, Habano W, Nakamura S, Uesugi N, Funato O, Saito K. Microsatellite instability in gallbladder carcinoma: Two independent genetic pathways of gallbladder carcinogenesis. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:768–774. doi: 10.1007/s005350070036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yanagisawa N, Mikami T, Yamashita K, Okayasu I. Microsatellite instability in chronic cholecystitis is indicative of an early stage in gallbladder carcinogenesis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;120:413–417. doi: 10.1309/BYRNALP8GN63DHAJ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagahashi M, Ajioka Y, Lang I, Szentirmay Z, Kasler M, Nakadaira H, Yokoyama N, Watanabe G, Nishikura K, Wakai T, et al. Genetic changes of p53, K-ras, and microsatellite instability in gallbladder carcinoma in high-incidence areas of Japan and Hungary. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:70–75. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shia J. Immunohistochemistry versus microsatellite instability testing for screening colorectal cancer patients at risk for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome. Part I. The utility of immunohistochemistry. J Mol Diagn. 2008;10:293–300. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2008.080031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shia J, Ellis NA, Klimstra DS. The utility of immunohistochemical detection of DNA mismatch repair gene proteins. Virchows Arch. 2004;445:431–441. doi: 10.1007/s00428-004-1090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shia J, Klimstra DS, Nafa K, Offit K, Guillem JG, Markowitz AJ, Gerald WL, Ellis NA. Value of immunohistochemical detection of DNA mismatch repair proteins in predicting germline mutation in hereditary colorectal neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:96–104. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000146009.85309.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hendriks YM, Jagmohan-Changur S, van der Klift HM, Morreau H, van Puijenbroek M, Tops C, van Os T, Wagner A, Ausems MG, Gomez E, et al. Heterozygous mutations in PMS2 cause hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma (Lynch syndrome) Gastroenterology. 2006;130:312–322. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palomaki GE, McClain MR, Melillo S, Hampel HL, Thibodeau SN. EGAPP supplementary evidence review: DNA testing strategies aimed at reducing morbidity and mortality from Lynch syndrome. Genet Med. 2009;11:42–65. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31818fa2db. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kakar S, Burgart LJ, Thibodeau SN, Rabe KG, Petersen GM, Goldberg RM, Lindor NM. Frequency of loss of hMLH1 expression in colorectal carcinoma increases with advancing age. Cancer. 2003;97:1421–1427. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tajima Y, Eguchi H, Chika N, Nagai T, Dechamethakun S, Kumamoto K, Tachikawa T, Akagi K, Tamaru JI, Seki H, et al. Prevalence and molecular characteristics of defective mismatch repair epithelial ovarian cancer in a Japanese hospital-based population. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2018;48:728–735. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyy081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Loilome W, Kadsanit S, Muisook K, Yongvanit P, Namwat N, Techasen A, Puapairoj A, Khuntikeo N, Phonjit P. Imbalanced adaptive responses associated with microsatellite instability in cholangiocarcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:639–646. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.5477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Umar A, Boland CR, Terdiman JP, Syngal S, de la Chapelle A, Rüschoff J, Fishel R, Lindor NM, Burgart LJ, Hamelin R, et al. Revised Bethesda Guidelines for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) and microsatellite instability. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:261–268. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hampel H, Frankel WL, Martin E, Arnold M, Khanduja K, Kuebler P, Clendenning M, Sotamaa K, Prior T, Westman JA, et al. Feasibility of screening for Lynch syndrome among patients with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5783–5788. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.5950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yurgelun MB, Kulke MH, Fuchs CS, Allen BA, Uno H, Hornick JL, Ukaegbu CI, Brais LK, McNamara PG, Mayer RJ, et al. Cancer Susceptibility Gene Mutations in Individuals With Colorectal Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1086–1095. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Valle JW. Advances in the treatment of metastatic or unresectable biliary tract cancer. Ann Oncol. 2010;21((Suppl 7)):vii345–vii348. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang SJ, Lemieux A, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Ord CB, Walker GV, Fuller CD, Kim JS, Thomas CR., Jr Nomogram for predicting the benefit of adjuvant chemoradiotherapy for resected gallbladder cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4627–4632. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.8020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Y, Li J, Xia Y, Gong R, Wang K, Yan Z, Wan X, Liu G, Wu D, Shi L, et al. Prognostic nomogram for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after partial hepatectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1188–1195. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.5984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Homet Moreno B, Ribas A. Anti-programmed cell death protein-1/ligand-1 therapy in different cancers. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:1421–1427. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dudley JC, Lin MT, Le DT, Eshleman JR. Microsatellite Instability as a Biomarker for PD-1 Blockade. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:813–820. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Kemberling H, Eyring A, Bartlett B, Goldberg RM, Crocenzi TS, Fisher GA, Lee JJ, et al. PD-1 blockade in mismatch repair deficient non-colorectal gastrointestinal cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34((Suppl 4)):195–195. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.34.15_suppl.103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.