Abstract

Objective:

To describe current state-level policies in the United States, January 1, 2007- June 1, 2017, limiting high Morphine Equivalent Daily Dose (MEDD) prescribing.

Methods:

State-level MEDD threshold policies were reviewed using LexisNexis and Westlaw Next for legislative acts and for non-legislative state-level policies using Google. The websites of each state’s Medicaid Agency, Health Department, Prescription Drug Monitoring Program, Workers’ Compensation Board, Medical Board, and Pharmacy Board were reviewed to identify additional policies. The final policy list was checked against existing policy compilations and academic literature and through contact with state health agency representatives. Policies were independently double coded on the categories: state, agency/organization, policy type, effective date, threshold level, and policy exceptions.

Results:

Currently, 22 states have at least one type of MEDD policy, most commonly guidelines (14 states) followed by prior authorizations (4 states), rules/regulations (4 states), legislative acts (3 states), claim denials (2 states), and alert systems/automatic patient reports (2 states). Thresholds range widely (30–300 mg MEDD) with higher thresholds generally corresponding to more restrictive policies (e.g., claim denial) and lower thresholds with less restrictive policies (e.g., guidelines). The majority of policies exclude some groups of opioid users, most commonly patients with terminal illnesses or acute pain.

Conclusions:

MEDD policies have gained popularity in recent years, but considerable variation in threshold levels and policy structure point to a lack of consensus. This work provides a foundation for future evaluation of MEDD policies and may inform states considering adopting such policies.

Keywords: Opioids, Prescriptions, Quality of Healthcare

Introduction

Prescription opioid misuse is a significant problem which has gained considerable national attention in recent years. In particular, between 2006 and 2015 the rate of prescription opioid mortality doubled (1), prompting the promulgation of recommendations and policies aimed at stemming the epidemic. While a robust body of literature details the epidemiology of prescription opioid misuse, there is a lack of consensus as to which policies are most effective at reducing mortality and improving patient outcomes (2). Previous research indicates that patients who receive higher doses of prescription opioids have an increased risk of overdose and mortality relative to patients who receive lower doses (3–5). Given this association, a commonly promoted tool to address the prescription opioid overdose epidemic is the establishment of Morphine Equivalent Daily Dose (MEDD) thresholds. MEDD, also sometimes referred to as daily Milligrams Morphine Equivalent (MME), is a measurement that converts opioid prescriptions to their equivalent dose in morphine and divides the total dose of the prescription by days supply (the number of days the prescription is intended to last) (6). For example, 1 mg of oxycodone is equal to 1.5 morphine equivalents (7), so a patient prescribed oxycodone following surgery and instructed to take one 5mg tablet and wait a minimum of six hours between doses would receive a maximum of 30 MEDD, if the prescription was taken as directed. MEDD allows for comparison among different types of opioid formulations and strengths and accounts for multiple prescriptions patients may simultaneously receive. The threshold levels and structures of these policies vary widely by the states and organizations that set them and are used in different ways to regulate prescribing practices.

The first MEDD policy was in the form of an interagency guideline passed by Washington State in 2007 (8). Since that time, multiple states have implemented some type of MEDD policy, though evaluations of these policies have been limited to Washington State (9–11). Other types of MEDD policies, such as rules/regulations, legislative acts, passive alert systems, prior authorization, and claim denial theoretically may have a greater impact on prescribing behavior, though these policies have not been well evaluated. However, prior research in other contexts supports the idea that these policies may be more effective than guidelines at changing prescriber behavior. These studies have generally found that adherence to published prescribing guidelines is low, even years after a guideline has been published (12–15). However, passive alert systems—systems that provide prescribing recommendations either through decision support within an Electronic Health Record (EHR), by e-mail or through paper letters during or shortly after eligible patient encounters—tended to significantly improve provider adherence to prescribing guidelines, particularly when the alerts were timely and provided a recommended course of action (12–14,16,17). Mandates, such as those provided through legislative acts, rules, and regulations, are also likely to influence prescriber behavior. In studies of state Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs), mandated use laws have reduced high-risk prescribing practices such as prescribing overlapping opioid prescriptions (18,19). Prior authorization policies, aimed at reducing prescribing rates of expensive or potentially dangerous drugs by requiring approval from the insurer before the drug can be dispensed, have been found to change prescribing behavior (20–22).

Little is known about the extent to which MEDD policies influence physician practice, but prescribing habits have clearly changed. After a steady increase in rates of opioid prescribing through the 1990s and early 2000s, overall opioid prescribing rates began to drop in 2010 across all levels of MEDD, with the largest drops seen among prescriptions >90 mg MEDD (23).

The purpose of this article is to systematically describe the landscape of MEDD policies at the state level. Currently, no comprehensive list of these policies exists. In this article, MEDD policies refer to state-level policies which seek to restrict cumulative opioid prescribing above a given MEDD threshold. Specific features of these policies are described and documented to lay the groundwork for future empirical evaluation of the effectiveness of MEDD policies.

Methods

Scope of Study

In this study, MEDD policies are defined as those which seek to restrict cumulative opioid prescribing above a given MEDD threshold and are one of the following policy types: guidelines/recommendations, legislative acts, rules/regulations, prior authorizations from an insurer, claim denials from an insurer, and alert systems/automatic patient reports. Definitions of each of these policies types are provided in Appendix 1 and detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria applied to the policies are given in the study protocol (Supplementary Data File S1, available online). Briefly, only policies from a defined set of state-level organizations (Medicaid agencies, health departments, PDMPs, state legislatures, workers’ compensation boards/divisions, medical boards, and pharmacy boards) were included in the final list of MEDD policies. Similarly, policies from any private company, non-profit organization, or any type of national organization were excluded unless they were co-sponsored by one of the above state-level organizations. Other key reasons for excluding policies were limiting MEDD for only certain types of opioids (e.g., non-preferred or short-acting), only limiting individual opioid prescriptions (as opposed to cumulative MEDD), or recommending increased follow-up after exceeding a given MEDD with no other recommended course of action.

Search Strategy

A systematic search of state-level MEDD policies January 1, 2007- June 1, 2017, was conducted. LexisNexis and Westlaw Next were used to conduct a comprehensive search of legislative acts in all 50 states and the District of Columbia using the terms “morphine equivalent,” “milligrams morphine,” “opioid dose threshold,” and “opioid dose maximum.” These same terms were also used to find non-legislative state-level policy documentation on Google. Additionally, each state Medicaid Agency, Health Department, Prescription Drug Monitoring Program, Workers’ Compensation Board/Division, Medical Board, and Pharmacy Board website was checked to determine if any other MEDD policies existed. The comprehensiveness of the list was validated in several ways. First, the list was checked against existing compilations of policies such as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) guideline clearinghouse (24), the Brandeis Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Center of Excellence’s report on PDMPs with passive alert systems (25), the National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws 2016 report on State Pain Management and Prescribing Policies (26), and the University of Wisconsin Pain and Policy Studies Group’s 2015 Report on Profiles of State Policies Governing Drug Control and Medical Pharmacy Practice (27). None of these compilations are comprehensive, cover the full range of policy types examined in this paper, or systematically code characteristics of the policies, but they do serve as useful checks on the completeness of the policy list identified in the current study. The Medicaid policies were checked against the Medicaid Drug Utilization Review Annual Report Survey (28), which lists states with Medicaid agencies responding “yes” to the question, “Have you set recommended maximum morphine equivalent daily dose measures?” Second, the list was checked against academic literature using the above search terms, for references to MEDD policies. Finally, for states with no MEDD policy found, at least one representative from a state health agency was contacted to confirm the lack of a formal policy. State and national opioid policies which involved MEDD but did not meet all of the study’s inclusion and exclusion criteria were collected and are available in an appendix (Supplementary Data File S2, available online) but should not be considered comprehensive.

Coding Strategy

After the final list of MEDD threshold policies was completed, documentation for each policy was reviewed to define a list of variables for coding each policy. The final list of variables included state, the effective date of the policy, organization(s) that contributed to the policy, policy type, threshold level, patient groups excluded from the policy, whether or not short courses of opioids were excluded from the policy, and under what circumstances the threshold level may be exceeded. Two researchers independently coded the first eight policies (alphabetically by state) and had a divergence rate of 33% defined as the percentage of questions as defined in the codebook with different answers, using a similar method to that used in previous policy mapping studies (29). Divergent codes were discussed and resolved and clarifying edits were then made to the codebook based on divergent answers. The two researchers then independently coded the remaining policies with a divergence rate of 21% and repeated the process of resolving differences in coding and clarifying the codebook based on divergent answers. The primary source of divergence was disagreement with definitions regarding patient groups excluded and circumstances under which the threshold level may be exceeded and codebook revisions involved adding more detail to be inclusive of the different language state policies used to describe these categories. In addition to the protocol, the final codebook (Supplementary Data File S3) and full dataset with coded policies (Supplementary Data File S4) are available online and at http://lawatlas.org/datasets/morphine-equivalent-daily-dose-medd-policies, a website managed by the Policy Surveillance Program of the Center for Public Health Law Research at Temple University’s Beasley School of Law. Policy data for individual states along with the text of the original policy can be viewed as part of an interactive map and is available at http://lawatlas.org/datasets/morphine-equivalent-daily-dose-medd-policies. The senior author’s Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Results

Between January 1, 2007, and June 1, 2017, 22 states (43% of all states) enacted 31 MEDD threshold policies (Table 1). The state-level agency or organization responsible for the policy was most frequently the state’s medical board (9 states), followed by Medicaid (6 states), workers’ compensation board/agency (5 states), health department (5 states), legislature (3 states), pharmacy board (2 states), and PDMP (2 states) with some state policies being implemented by multiple agencies or organizations (Table 1).

Table 1.

Frequency of policy characteristics

| States, Number (%) N=22 | Policies, Number (%) N=31 | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of Policy | ||

| Guideline | 13 (59%) | 15 (48%) |

| Rule/Regulation | 4 (18%) | 4 (13%) |

| Prior Authorization | 4 (18%) | 4 (13%) |

| Legislative Act | 3 (14%) | 4 (13%) |

| Claim Denial | 2 (9%) | 2 (6%) |

| Alert System/Automatic Patient Report | 2 (9%) | 2 (6%) |

| Sponsoring Organization | ||

| Medical Board | 9 (41%) | 9 (29%) |

| Medicaid | 6 (27%) | 7 (23%) |

| Workers’ Compensation | 5 (23%) | 6 (19%) |

| Health Department | 5 (23%) | 5 (16%) |

| State Legislature | 3 (14%) | 4 (13%) |

| Pharmacy Board | 2 (9%) | 2 (6%) |

| Prescription Drug Monitoring Program | 2 (9%) | 2 (6%) |

| Threshold Level | ||

| 30 | 2 (9%) | 2 (6%) |

| 50 | 1 (5%) | 1 (3%) |

| 60 | 1 (5%) | 1 (3%) |

| 80 | 3 (14%) | 4 (13%) |

| 90 | 4 (18%) | 4 (13%) |

| 100 | 5 (23%) | 5 (16%) |

| 120 | 10 (45%) | 11 (35%) |

| 300 | 2 (9%) | 2 (6%) |

| Patient exclusions | ||

| Terminal/hospice/palliative care patients | 12 (55%) | 14 (45%) |

| Acute/etiologic pain | 10 (45%) | 10 (32%) |

| Cancer/malignant pain | 8 (36%) | 11 (35%) |

| Long-term care facility/nursing home patients | 5 (23%) | 5 (16%) |

| Emergency Room care patients | 2 (9%) | 2 (6%) |

| Other patient groups | 3 (14%) | 3 (10%) |

| No patient groups excluded | 7 (32%) | 7 (23%) |

| Short courses of opioids excluded | 5 (23%) | 5 (16%) |

| Excluded circumstances | ||

| Specialist consulted | 14 (64%) | 15 (48%) |

| Pain contract/patient education | 7 (32%) | 7 (23%) |

| Evidence of tapering | 4 (18%) | 4 (13%) |

| Clinical judgment | 6 (27%) | 7 (23%) |

| Improved pain or function | 5 (23%) | 5 (16%) |

| Prescription Drug Monitoring Program checked | 4 (18%) | 4 (18%) |

| Drug testing | 3 (14%) | 3 (10%) |

| Other circumstances specified | 3 (14%) | 3 (10%) |

| No circumstances specified | 9 (41%) | 10 (32%) |

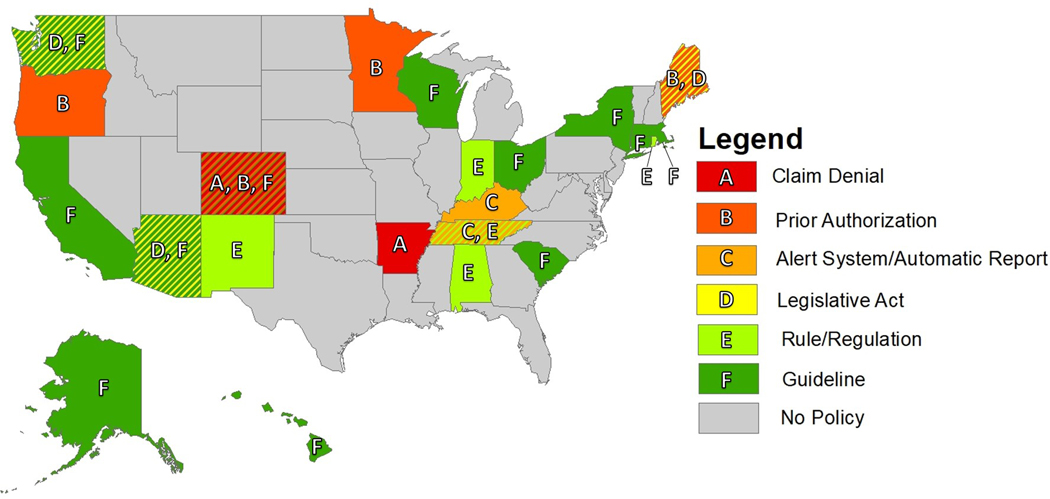

The most common policy structure observed was guideline (13 states) followed by prior authorization (4 states), rule/regulation (4 states), legislative act (3 states), claim denial (2 states), and alert system/automatic patient report (2 states). Notably, all prior authorization and claim denial policies meeting study criteria were implemented by state Medicaid agencies. A map of policy type by state is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Map of state by policy type

The majority of states explicitly excluded certain patient groups from their MEDD policies with the most common exceptions being for terminal/hospice/palliative care patients (12 states), acute/etiologic pain patients (10 states), and cancer/malignant pain patients (8 states) (Table 1). The majority of states also had policies which specified circumstances under which MEDD thresholds could be exceeded or triggered recommended or required actions when a threshold was exceeded. Most commonly, these circumstances involved referral to a specialist (14 states), pain contract/patient education (7 states), clinical judgment (6 states), or improved pain or function (5 states). Five states made exceptions for short courses of opioids, defined as less than 90 days (4 states) or 4 days (1 state).

The first policy was in the form of a guideline implemented in 2007 by Washington State which recommended against prescribing above 120 MEDD. This guideline has served as a model for other states with a plurality of states (10) adopting the 120 MEDD threshold (Table 1).

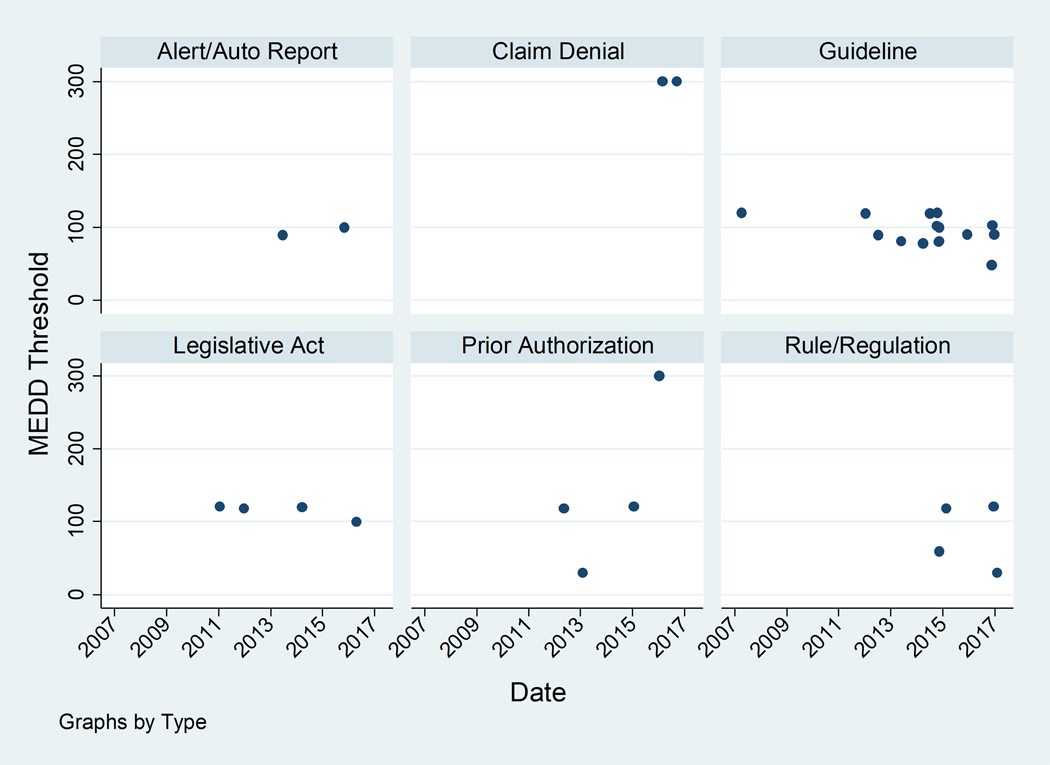

Since Washington state’s first 120 MEDD guideline in 2007, progressively lower guideline thresholds have been introduced with three of four guidelines introduced 2016–2017 ≤90 (Figure 2). Other types of policies with a higher potential impact on prescribing behavior have also been introduced in more recent years. While it is difficult to comment on trends given the small number of each of these types of policies, it is notable that the two claim denial policies have the highest thresholds (300 MEDD) and three of the four prior authorization policies have thresholds ≥120 MEDD (Figure 2). Thresholds may be higher for claim denial and prior authorization as these policies put restrictions on prescriber autonomy. In general, early policies had higher thresholds that were broadly applied. More recent policies have lower thresholds and stricter enforcement mechanisms but are more specific about who the policy is intended to cover. For example, the 21 policies enacted prior to 2016 had a median of one patient exclusion group per policy, while the 10 policies enacted 2016–2017 had a median of 2.5 patient exclusion groups per policy (data not shown).

Figure 2.

MEDD thresholds and policy structures over time

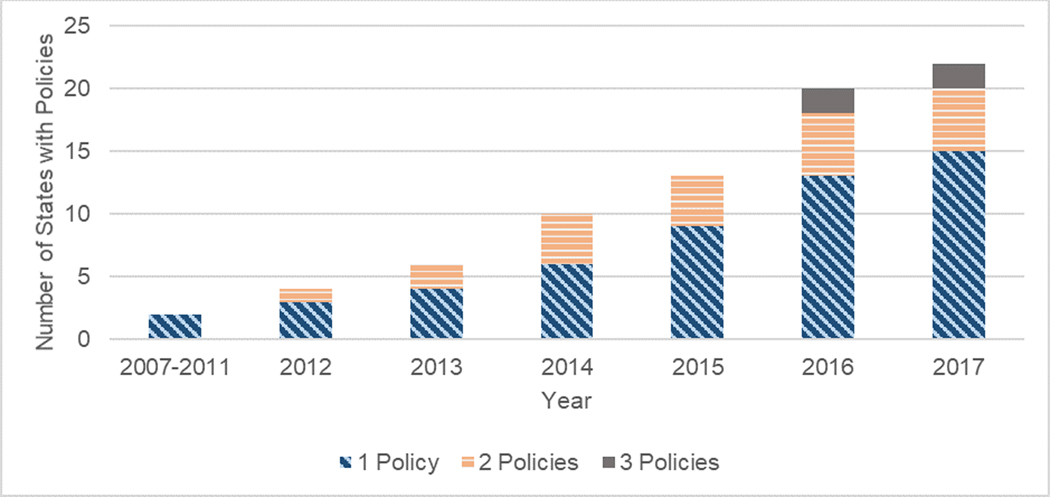

Seven states have enacted multiple policies (Figure 3). In some cases, states have moved from less restrictive to more restrictive policy types. For example, Colorado released a guideline in 2014, then implemented prior authorization and claim denial in 2016. Other states have had multiple organizations implement guidelines or have lowered their thresholds with subsequent guideline releases.

Figure 3.

Number of states with MEDD policies over time

Discussion

MEDD policies have proliferated from 2007–2017 from a single policy in 2007 to 31 policies across 22 states in 2017. However, there is significant variation in these policies. Overall, there has been a trend away from guidelines to more restrictive policy types as well as a decrease in threshold level. Most policies explicitly acknowledge that MEDD threshold levels should not apply to certain patient groups or the policies allow for circumstances under which thresholds may be exceeded.

Reducing MEDD has been a strong policy area of focus due to the relationship between high MEDD prescribing and opioid mortality. This paper focuses on policies with the explicit goal of reducing high MEDD prescribing. However, it is important to note that states have implemented a number of other policy strategies to restrict opioid prescribing (30) and that the lack of a MEDD policy should not be construed as a lax regulatory opioid environment for a state. Many types of prescription opioid policies exist, and MEDD policies are only one way of influencing prescribing behavior. Some states with no MEDD policy that meets this study’s criteria have other types of opioid policies including Medicaid lock-in programs for opioid users (31), formularies that require prior authorization for some or all types of opioids (32), quantity limits for individual types of opioids (33), or limits on days’ supply of opioids (34). While none of these policies meets this study’s definition of a MEDD policy, it is reasonable to expect that these types of policies may nonetheless lower the overall MEDD prescribed.

Conversely, it is also important to note that MEDD threshold policies may not always work as intended. While the MEDD policies included in this study are all intended to restrict cumulative MEDD, in practice, prescribers may not account for opioid prescriptions from other sources or early prescription refills when calculating MEDD. On a more basic level, there is a lack of understanding among providers as to how MEDD is calculated and multiple, sometimes conflicting, conversion standards exist (35). Furthermore, conversion tables may not be up to date and may exclude recently approved or newly formulated opioids. A 2015 study sent a survey to pharmacists, physicians, nurse practitioners, and physicians assistants asking them to calculate the morphine equivalents for four different drugs using any resources available to them (36). For each drug and among each provider group, their calculations had large standard deviations relative to the mean dose calculated ranging from to 39.9 MEDD for oxycodone (mean= 174.8 MEDD) to 150 MEDD for fentanyl (mean= 186.1 MEDD). While a small number of policies provide mechanisms to automatically calculate MEDD and account for multiple and overlapping prescriptions (e.g., the two states with alert systems/automatic reports), most policies rely on the provider to make these calculations.

Beyond the practical consideration of calculating MEDD, there is also a broader criticism of MEDD as a measure. Many have argued that MEDD policies dangerously downplay important differences between different opioid formulations or fail to take into account individual differences in body mass and drug tolerance (36–39).

In March of 2016, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) implemented their own MEDD guideline which stated that prescribers “should carefully reassess evidence of individual benefits and risks when increasing dosage to ≥50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME)/day, and should avoid increasing dosage to ≥90 MME/day or carefully justify a decision to titrate dosage to ≥90 MME/day (40).” The guideline was well publicized, and one might expect that following the passage of this guideline there would be less variation in MEDD threshold level for new policies. While recent research studies indicate that prescribers are aware of the CDC guidelines (41) and may be changing their prescribing practices accordingly (42), this change did not appear to have substantial influence on state-level MEDD policies. Of the seven state-level policies enacted following the CDC guideline, threshold values varied widely (30–300 MEDD), and only two of those states (Alaska and Wisconsin) set thresholds in line with CDC recommendations (50–90 MEDD). The continued variation in policy may be due to the cautious language used by the CDC in endorsing a dose threshold or it may be that only states which did not agree with the CDC guidelines felt that it was necessary to implement their own policies. Further research on states’ processes for setting threshold levels is necessary to understand why such variation has persisted.

Other federal-level and private initiatives have been implemented or will soon be implemented, further changing the landscape of MEDD policies in the United States. Notable examples include a 2018 Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) quality measure which assesses the rate patients receiving long-term opioids >120 MEDD (43), the 2018 90 MEDD prior authorization requirements by the pharmacy benefits manager CVS Caremark™ (44), and passive alerts for Medicare Part D beneficiaries that will trigger a consultation and documented discussion of intent with the prescriber over 90 MEDD to be implemented in 2019 (45).

In addition to processes by which states set thresholds, understanding a number of other policy characteristics not explored here may be of great interest and aid in the future evaluation of these policies. In particular, information about enforcement mechanisms was often lacking from the policy documentation. For example, Medical Board Rules are stated as imperatives, and, in theory, violating these rules may result in losing one’s medical license. However, it is unclear how frequently this happens in practice. It is not clear that these states have any automated way of verifying these rules are followed and noncompliance may only be discovered during audits of high volume prescribers. Conversely, guidelines, which do not use imperative language, may nonetheless make big impacts on prescribing behavior. Guidelines can be used by individual insurers within a state to justify claim denial of high dose prescriptions or target high dose prescribers for utilization review. Understanding the nuanced mechanisms by which MEDD threshold policies influence provider behavior would require in-depth qualitative research that is beyond the scope of this manuscript but is an important area for future research.

Conclusions

MEDD thresholds are a promising policy tool, but there is a lack of consensus as to how the thresholds should be used and at what threshold level they should be set. Further research is needed to determine which types of policies are most effective, if they target patients most at-risk for overdose, and potential unintended consequences on appropriate opioid prescribing. This study systematically identifies state-level MEDD policies and defines several key features of these policies. This work serves as an important foundation for researchers who wish to evaluate MEDD policies by allowing them to choose appropriate control and treatment states and account for variations in policy structure. Additionally, this study may provide guidance to states which are considering adopting or revising MEDD policies and wish to better understand available policy options.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Adrian Ghorashi, Lindsay Cloud, Bethany Saxon, and the Policy Surveillance Program at Temple University’s Center for Public Health Law Research for their assistance with quality assurance and dissemination of the work and Keshia Pollack Porter, Colleen Barry, and Andrea Gielen for their feedback on the manuscript. They also thank Hilary Peterson for manuscript preparation.

Funding: This work was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Grant No.: R36 HS25557

Appendix 1.

Policy type definitions

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Guideline/recommendation | Provides a recommended threshold over which prescribers should not exceed or should only exceed if special precautions are taken. Guidelines/recommendations have no mechanism of enforcement. |

| Rules/regulations | Similar to guidelines, but are stated as an imperative (e.g., “must” “shall”) and may or may not have an explicit means of enforcement. |

| Legislative Act | Similar to guidelines, but are stated as an imperative (e.g., “must” “shall”) and may or may not have an explicit means of enforcement. |

| Legislative Act | Any law passed by the state’s legislative body which has gone into effect. Proposed bills that never became law are not included. |

| Alert System/Automatic Patient Report | A mechanism by which targeted, unsolicited letters or alerts sent either by mail or electronically and inform prescribers that patients under their care have exceeded a given MEDD threshold. Follow-up action may or may not be required. |

| Prior Authorization | A requirement that mandates prior approval from a third party before prescriptions above a given MEDD threshold may be filled. |

| Claim Denial | A mechanism by which a third party denies prescription fills above a given MEDD threshold. In cases where Prior Authorization documentation explicitly states that prescriptions above a given MEDD threshold will not be approved, Prior Authorization and Claim Denial may be coded as two distinct policies. |

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Disclosure Summary

Dr. Alexander is Chair of FDA’s Peripheral and Central Nervous System Advisory Committee, has served as a paid advisor to IQVIA, serves on the advisory board of MesaRx Innovations, is a member of OptumRx’s National P&T Committee; and holds equity in Monument Analytics, a health care consultancy whose clients include the life sciences industry as well as plaintiffs in opioid litigation. This arrangement has been reviewed and approved by Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. Drs. Frey and Castillo are employed by Johns Hopkins University and Dr. Heins is employed by RAND Corporation and have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.O’Donnell JK. Trends in Deaths Involving Heroin and Synthetic Opioids Excluding Methadone, and Law Enforcement Drug Product Reports, by Census Region — United States, 2006–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66(34):897–903.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haegerich TM, Paulozzi LJ, Manns BJ, Jones CM. What we know, and don’t know, about the impact of state policy and systems-level interventions on prescription drug overdose. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014;145:34–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, et al. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2010;152(2):85–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohnert ASB, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA J Am Med Assoc 2011;305(13):1315–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomes T, Mamdani MM, Dhalla IA, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN. Opioid dose and drug-related mortality in patients with nonmalignant pain. Arch Intern Med 2011;171(7):686–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ripamonti C, Groff L, Brunelli C, Polastri D, Stavrakis A, De Conno F. Switching from morphine to oral methadone in treating cancer pain: what is the equianalgesic dose ratio? J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 1998;16(10):3216–3221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Data Resources | Drug Overdose | CDC Injury Center. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/resources/data.html. Published November 2, 2018. Accessed December 14, 2018.

- 8.Washington Department of Labor and Industries. Interim Evaluation of the Washington State Interagency Guideline on Opioid Dosing for Chronic Non-Cancer Pain. 2009. http://www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/files/agreportfinal.pdf.

- 9.Franklin GM, Mai J, Turner J, Sullivan M, Wickizer T, Fulton‐Kehoe D. Bending the prescription opioid dosing and mortality curves: impact of the Washington State opioid dosing guideline. Am J Ind Med 2012;55(4):325–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fulton‐Kehoe D, Garg RK, Turner JA, et al. Opioid poisonings and opioid adverse effects in workers in Washington State. Am J Ind Med 2013;56(12):1452–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fulton-Kehoe D, Sullivan MD, Turner JA, et al. Opioid poisonings in Washington State Medicaid: trends, dosing, and guidelines. Med Care 2015;53(8):679–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kooij FO, Klok T, Hollmann MW, Kal JE. Decision Support Increases Guideline Adherence for Prescribing Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting Prophylaxis: Anesth Analg 2008;106(3):893–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tooher R, Middleton P, Pham C, et al. A Systematic Review of Strategies to Improve Prophylaxis for Venous Thromboembolism in Hospitals. Ann Surg 2005;241(3):397–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abraham NS, El–Serag HB, Johnson ML, et al. National Adherence to Evidence-Based Guidelines for the Prescription of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Gastroenterology 2005;129(4):1171–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinmann S, Janssen B, Gaebel W. Guideline adherence in medication management of psychotic disorders: an observational multisite hospital study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2005;112(1):18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, Lobach DF. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ 2005;330(7494):765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eslami S, de Keizer NF, Abu-Hanna A. The impact of computerized physician medication order entry in hospitalized patients—A systematic review. Int J Med Inf 2008;77(6):365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bao Y, Wen K, Johnson P, Jeng PJ, Meisel ZF, Schackman BR. Assessing The Impact Of State Policies For Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs On High-Risk Opioid Prescriptions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018;37(10):1596–1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buchmueller TC, Carey C. The Effect of Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs on Opioid Utilization in Medicare. Am Econ J Econ Policy 2018;10(1):77–112. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dillender M. What happens when the insurer can say no? Assessing prior authorization as a tool to prevent high-risk prescriptions and to lower costs. J Public Econ 2018;165:170–200. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keast SL, Kim H, Deyo RA, et al. Effects of a prior authorization policy for extended-release/long-acting opioids on utilization and outcomes in a state Medicaid program. Addiction 2018;113(9):1651–1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smalley WE, Griffin MR, Fought RL, Sullivan L, Ray WA. Effect of a prior-authorization requirement on the use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs by Medicaid patients. N Engl J Med 1995;332(24):1612–1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.2018 Annual Surveillance Report of Drug-Related Risks and Outcomes - United States. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327427649_2018_Annual_Surveillance_Report_of_Drug-Related_Risks_and_Outcomes_-_United_States. Accessed November 28, 2018.

- 24.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National Guideline Clearinghouse. 2016. http://www.guideline.gov/index.aspx.

- 25.Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Center of Excellence at Brandeis. Options for Unsolicited Reporting; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.The National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws (NAMSDL). http://www.namsdl.org/. Accessed October 23, 2017.

- 27.Pain & Policy Studies Group. Profiles of State Policies Governing Drug Control and Medical and Pharmacy Practice. University of Wisconsin; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicaid Drug Utilization Review State Comparison/Summary Report FFY 2015 Annual Report; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harvey HH Reducing traumatic brain injuries in youth sports: youth sports traumatic brain injury state laws, January 2009–December 2012. Am J Public Health 2013;103(7), 1249–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis CS, Lieberman AJ, Hernandez-Delgado H, Suba C. Laws limiting the prescribing or dispensing of opioids for acute pain in the United States: A national systematic legal review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2019;194:166–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pew Charitable Trusts. Curbing Prescription Drug Abuse With Patient Review and Restriction Programs. http://pew.org/1q69pHC. Accessed September 6, 2017.

- 32.Texas Department of Insurance. Texas Reduces Costs, Opioid Use with Closed Formulary. 2016. https://www.tdi.texas.gov/news/2016/dwc08162016.html. Accessed December 27, 2018.

- 33.Riggs CS, Billups SJ, Flores S, Patel RJ, Heilmann RMF, Milchak JL. Opioid Use for Pain Management After Implementation of a Medicaid Short-Acting Opioid Quantity Limit. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2017;23(3):346–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.New Prescribing Law For Treatment of Acute and Chronic Pain | NJAFP. https://www.njafp.org/content/new-prescribing-law-treatment-acute-and-chronic-pain. Accessed November 27, 2017.

- 35.Reddy A, Vidal M, Stephen S, et al. The Conversion Ratio From Intravenous Hydromorphone to Oral Opioids in Cancer Patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;54(3):280–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rennick A, Atkinson T, Cimino NM, Strassels SA, McPherson ML, Fudin J. Variability in Opioid Equivalence Calculations. Pain Med 2016;17(5):892–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ziegler SJ. The Proliferation of Dosage Thresholds in Opioid Prescribing Policies and Their Potential to Increase Pain and Opioid‐Related Mortality. Pain Med 2015;16(10):1851–1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fudin J, Raouf M, Wegrzyn EL, Schatman ME. Safety concerns with the Centers for Disease Control opioid calculator. J Pain Res 2017;11:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Unintended Harm from Opioid Prescribing Guidelines - Fishman - 2009 - Pain Medicine - Wiley Online Library. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00553.x/abstract. Accessed October 9, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. Recommendations and Reports 2016;65(1);1–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jean C. McCalmont, Kim D. Jones P, Robert M. Bennett MD, Ronald Friend P. Does familiarity with CDC guidelines, continuing education, and provider characteristics influence adherence to chronic pain management practices and opioid prescribing? J Opioid Manag 2018;14(2):103–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bohnert ASB, Guy GP, Losby JL. Opioid Prescribing in the United States Before and After the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2016 Opioid Guideline. Ann Intern Med 2018;169(6):367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.NCQA Updates Quality Measures for HEDIS 2018. NCQA. https://www.ncqa.org/news/ncqa-updates-quality-measures-for-hedis-2018/. Accessed November 29, 2018.

- 44.The Balancing Act. CVS Health Payor Solutions. https://payorsolutions.cvshealth.com/insights/balancing-act. Accessed November 29, 2018.

- 45.2019 Medicare Advantage and Part D Rate Announcement and Call Letter | CMS. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/2019-medicare-advantage-and-part-d-rate-announcement-and-call-letter. Accessed November 29, 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.