Abstract

Introduction

Cathepsin L (CTSL) is a kind of the SARS-entry-associated CoV-2's proteases, which plays a key role in the virus's entry into the cell and subsequent infection. We investigated the association between the expression level of CTSL and overall survival in Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) patients, to better understand the possible route and risks of new coronavirus infection for patients with GBM.

Methods

The expression level of CTSL in GBM was analyzed using TCGA and CGGA databases. The relationship between CTSL and immune infiltration levels was analyzed by means of the TIMER database. The impact of CTSL inhibitors on GBM biological activity was tested.

Results

The findings revealed that GBM tissues had higher CTSL expression levels than that of normal brain tissues, which was associated with a significantly lower survival rate in GBM patients. Meanwhile, the expression level of CTSL negatively correlated with purity, B cell and CD8+ T cell in GBM. CTSL inhibitor significantly reduced growth and induced mitochondrial apoptosis.

Conclusion

According to the findings, CTSL acts as an independent prognostic factor and can be considered as promising therapeutic target for GBM.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00432-021-03843-9.

Keywords: Glioblastoma, CTSL, COVID-19, Prognosis, Immune cell infiltration

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is highly infectious and transmitted mainly by inhaling droplets or aerosols released by an infected individual and possibly by a feco-oral transmission route, has accumulated 160,317,950 confirmed cases globally until mid-May 2021 (https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/). Understanding the mechanism of action of the virus is an important step in determining the best treatment. It has been reported that SARS-CoV2 enters host cells via spike proteins that bind to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) membrane-bound protein (Gemmati et al. 2020). After binding to target cells, the S protein is cleaved into two subunits: S1 and S2 by TMPRSS2 and host cell proteases such as cathepsin L (CTSL), which promotes viral entry into the cell by inducing membrane fusion and endocytosis of several coronaviruses. This cleavage of S protein by host proteases is critical for viral activation and subsequent infection (Hou et al. 2020; Hoffmann et al. 2020). Infection by SARS-CoV-2 results in significant morbidity and mortality. While the lung is the major organ of infection, some studies implied that SARS-CoV-2 might invade the CNS, causing neurological disorders (Narayanappa et al. 2021). Neurological symptoms, such as headache, dizziness, and impaired consciousness as well as symptoms involving the cranial nerves have been reported in COVID-19 patients (Achar and Ghosh 2020).

CTSL, a member of the lysosomal cysteine protease family, plays a role in lysosomal protein degradation in most cell types (Nakagawa 1998). CTSL expressing on the surface of cancer cells and secreted into the extracellular matrix to degrade extracellular matrix components. CTSL preferentially cleaves the peptide bond between the aromatic residue at the p2 position and the hydrophobic residue at the P3 position (Brady et al. 2000). The acidic environment in lysosomes promotes the activation of proteolytic enzymes. In addition, the locally acidic environment caused by anaerobic glycolysis also activates extracellular CTSL, which encourages the invasion of cancer cells into surrounding tissues, blood and lymphatic vessels, and the metastasis of tumor tissue to distant tissues (Sudhan and Siemann 2013). Previous studies have shown that the high expression of CTSL significantly promotes the proliferation, invasion, migration, drug resistance and angiogenesis in lung cancer, gastric cancer, ovarian cancer, breast cancer, glioma and other malignant tumors (Yao et al. 2018; Sigloch et al. 2017). Shan et al. (2016) found that the over-expressed transcription factor Forkhead box O3a (FOXO3a) in gastric cancer cells can activate the promoter of CTSL, inhibit the expression of E-cadherin, and promote the development of gastric cancer. CTSL inhibitors can reduce the tumor model’s ability to form blood vessels (Sudhan et al. 2016).

The pathogenesis of tumors is relatively complex, involves a variety of pathophysiological processes, and is affected by a variety of factors, among which the immune status of the body cannot be ignored. In the process of tumor occurrence and development, the immune response of the organism is often weakened (Leskowitz et al. 2015). Due to the low immune function of patients with malignant tumors and the suppression of the systemic immune system caused by anti-tumor treatments such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy or surgery, tumor patients are more susceptible to SARS-CoV2 than non-tumor patients (Addeo and Friedlaender 2020). In addition, the expression of SARS-CoV2 receptors (ACE2, CTSL and TMPRSS2) significantly increased in many kinds of tumors, which makes viral entry into the cell and cancer patients more susceptible to SARS-CoV2 (Bao et al. 2020).

Analyses of the expression and related biological processes of CTSL in GBM are useful to aid in the understanding of COVID-19 pathogenesis and the development of therapeutic strategies. In the present study, CTSL expression was identified using TCGA and GEPIA databases. Furthermore, the diagnostic and prognostic values of CTSL in GBM were determined. Subsequently, we evaluated whether CTSL can be regarded as a therapeutic target for GBM.

Materials and methods

Reagents

CTSL inhibitor 1 was purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Shanghai, China). Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) was purchased from Dojindo Molecular Technologies (Kumamoto, Japan). PE Annexin V apoptosis detection commercial kit were purchased from BD Biosciences (Shanghai, China). Cell-Light EdU Apollo567 in Vitro Kit was purchased from Guangzhou Ruibo Biotechnology Co. LTD (Guangzhou, China). Anti-CTSL, anti-Bax, anti-Bcl-2 and anti-MMP-9 antibodies were obtained from Proteintech (Wuhan, China). Anti-GAPDH was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK).

Data collection

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; https://www.cancer.gov/tcga) was used to obtain GBM RNA-seq data. A total of 35 GBM and 16 normal brain tissue samples were acquired with signed informed consent from Lanzhou University Second Hospital. Normal brain tissue samples were obtained from patients without glioma who underwent surgery for other reasons, including cerebral trauma. All procedures involving human samples were approved by the Ethics Committee of Lanzhou University Second Hospital.

Survival analysis

The prognostic value of CTSL was analyzed using CGGA (http://www.cgga.org.cn/). The overall survival (OS) rates of the patients in the high-level and low-level GBM groups were evaluated using Kaplan–Meier analysis.

TIMER database analysis

TIMER is a database (https://cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer/) for systematic analysis of immune information of various types of tumors (Deng et al. 2020). The TIMER database contains data from a total of 10,897 samples of 32 cancers from TCGA and can assess the abundance of tumor immune infiltration. The “Gene” module was used to analyze the correlation between the expression level of CTSL and the abundance of immune cell infiltration in GBM.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from tissues using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Then, reverser anscribed with the reverse transcription kit (RR037A, Takara Bio, Japan). The expression of mRNAs of CTSL were determined with a LightCycler (RR390Q, Takara Bio, Japan) using TB SYBR green Premix Ex Taq II (Takara Bio, Japan). And the results were analyzed by 2−ΔΔCT method. The following primers were used: CTSL forward, 5'- GAAAGGCTACGTGACTCCTGTG -3' and reverse, 5'- CCAGATTCTGCTCACTCAGTGAG -3'; GAPDH, forward 5'-GGACCTGACCTGCCGTCTAG -3' and reverse, 5'-TAG CCCAGGAGGATGCCCTTGAG-3'.

CCK8 and Edu assays

U251 cells were inoculated in 96-well plates and treated with BCA for 24 h, 48 h and 72 h. Each well is added 10 µL of CCK8, incubated for 2 h at 37 °C incubator, and then detected absorbance with a microplate reader. U251 cells were seeded in 96-well plates, each well is added 100 µL of 50 uM Edu solution, incubated for 2 h at 37 °C incubator, and then 4% Paraformaldehyde fixation. Wash with PBS for three times, and each well is added 100 µL 1 × Hoechst33342 solution, incubated at 37 °C in the dark for 30 min, then observed and analyzed under a fluorescence microscope.

Apoptosis analysis

U251 cells were treated with 0, 50, and 100 μmol/L BCA for 48 h. Then, U251 cells (1 × 106) were collected, after which 5 µL of PE Annexin V and 5 µL of 7-AAD were added. Gently vortex the cells and incubate at 25 °C in the dark for 15 min and the suspension was analyzed by flow cytometry (BD FACSCanto™ low cytometry, USA).

Wound healing assay

CTSL inhibitor-treated U251 cells were inoculated into a six-well plate. When the cells reach a confluence of 70–80%, were gently and slowly scratched with a new 200 µL pipette tip. The relative distance of the cells migrating was monitored and measure using a bright-field microscope at 0, 12 and 24 h.

Transwell cell migration assay

Transwell chambers membrane was pre-coated with diluted Matrigel (1:8 BD Biosciences). About 1 × 106 cells in 100 µL serum-free medium were added into the top chambers, and 600 µL DMEM medium was added into the lower chamber. After 24 h. the chambers were washed and cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and subsequently stained with 0.1% crystal violet. Cell invasion assay was performed as above except used the cell culture inserts coated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences).

Western blot

U251 cells (2 × 106) were lysed using RIPA buffer (Solarbio, China). The lysed cells were centrifuged at 12,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. Proteins were loaded on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes. The band was visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence with imageQuant LAS 500 system.

Statistical analyses

SPSS version 23.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) and R software v4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) were used to perform statistical analyses and graphing. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method with the log-rank test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

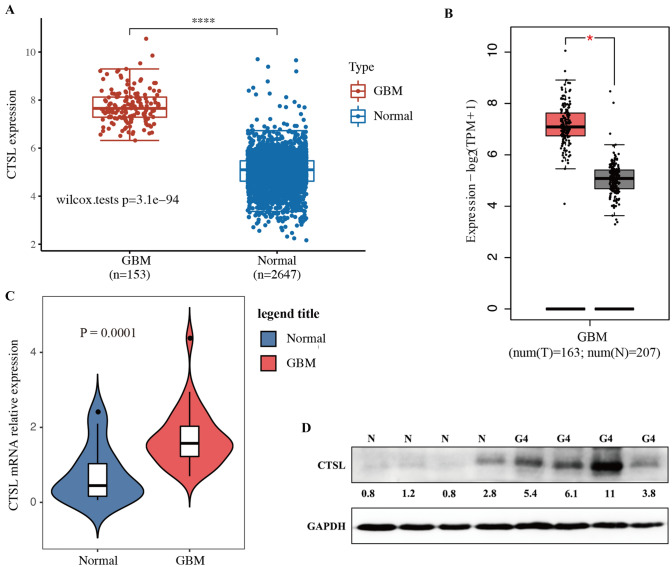

Expressions of CTSL in GBM

To elucidate the expression of CTSL in GBM, we analyzed the TCGA and GEPIA database. The level of CTSL expression was markedly upregulated in GBM (P < 0.05; Fig. 1A, B). The expression level of CTSL was confirmed using RT-qPCR and western blotting in GBM tissues (n = 35) and normal brain tissues (n = 16) to confirm the GEPIA database findings. The results showed that the level of CTSL was significantly increase in GBM (P < 0.05; Fig. 1C, D). Meanwhile, the data was consistent with TCGA and GEPIA database analysis. The correlation between the clinicopathological characteristic and the expression of CTSL was evaluated in the cases of 35 GBM patients. The median mRNA level of CTSL was used as a cut-off value. However, the CTSL expression levels was not significantly associated with any of the other parameters assessed, including age, sex, and Karnofsky Performance Status (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

The expression level of CTSL increases in GBM. A The CTSL mRNA expression level was analysis in TCGA database. B The CTSL mRNA expression level was analyzed in GEPIA database. C Expression of CTSL mRNA in GBM tissues were tested by RT-qPCR. D The protein expression levels of CTSL in patients with GBM were analyzed by western blotting. *P < 0.05 and ****P < 0.001

Table 1.

Association of the expression level of CTSL mRNA with clinicopathological factors of glioma

| Clinicopathological features | Patients (n) | CTSL mRNA expression | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (n) | High (n) | |||

| Age | ||||

| > 50 | 20 | 11 | 9 | 0.826 |

| ≤ 50 | 15 | 7 | 8 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 22 | 11 | 11 | 0.625 |

| Female | 13 | 7 | 6 | |

| KPS | ||||

| > 80 | 14 | 9 | 5 | 0.214 |

| ≤ 80 | 21 | 9 | 12 | |

KPS Karnofsky Performance Status

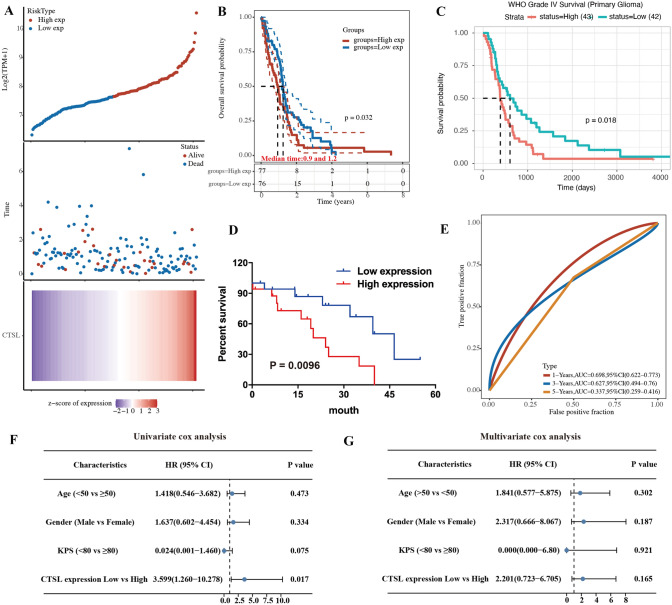

The effect of the expression of CTSL on prognosis in GBM

To determine whether CTSL can been regarded as an independent prognostic factor for GBM patients, the correlation between OS and the expressions of CTSL was evaluated in the cases of GBM patients using Kaplan–Meier analysis and log-rank tests. The results indicated that patients with high expression of CTSL had a lower OS rate than patients with low expression of CTSL (P = 0.035; Fig. 2D). In addition, we further verified the results coming from TCGA and CGGA databases (Fig. 2B, C). To further identify the diagnostic value of CTSL in GBM patients, ROC curve analysis was performed. The results showed (Fig. 2E) that the AUC for 1, 3, and 5 years were 0.698 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.622–0.733), 0.627 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.494–0.76), and 0.337(95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.259–0.416), respectively (Fig. 2E). It is suggested that the CTSL has higher prognostic value in the GBM. Furthermore, the correlations between CTSL expression and major clinic pathological factors were determined using Cox regression analysis. Univariate Cox regression analysis revealed that CTSL expression was an independent prognostic factor for OS in patients with GBM (hazard ratio, 3.599; 95% CI 1.260–10.278; P = 0.017; Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2.

Evaluation of the relationship between the CTSL and patient prognosis. A The curve of risk score. Survival status of the patients. More dead patients corresponding to the higher risk score. Heatmap of the expression profiles of CTSL in low- and high-expression group. B Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of CTSL in the TCGA set. C Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of CTSL in the CGGA database. D Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of CTSL in the GBM tissue. E Time-dependent ROC analysis of the CTSL in the TCGA set. F Univariate Cox regression forest map. G Multivariate Cox regression forest map

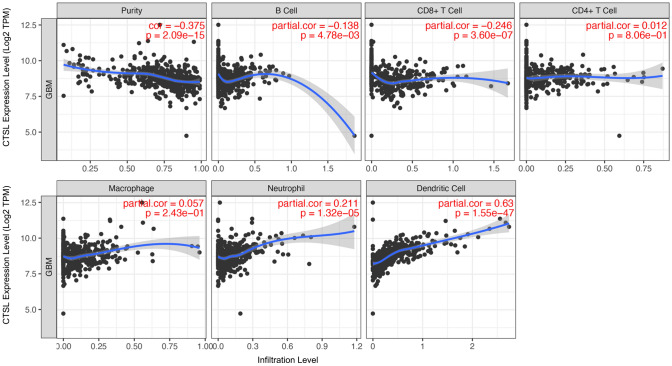

Relationship between CTSL expression and tumor immune infiltration

To have a better understanding of CTSL and the tumor immune microenvironment, we analysis the relationship between CTSL expression and tumor immune infiltration using TIMER database. Purity of the tumor means the tumor cell proportion in the tissue. The results showed that CTSL was very negatively correlated with purity (r = − 0.375, P < 0.001), B cell (r = − 0.138, P < 0.01) and CD8+ T cell (r = − 0.246, P < 0.001). However, the expression of CTSL was positively correlated with the level of immune infiltration of dendritic cell neutrophil (r = 0.211, P < 0.001) and dendritic cell (r = 0.63, P < 0.001) in GBM (Fig 3).

Fig. 3.

Correlation between CTSL expression and tumor immune infiltration levels in GBM through TIMER database analysis

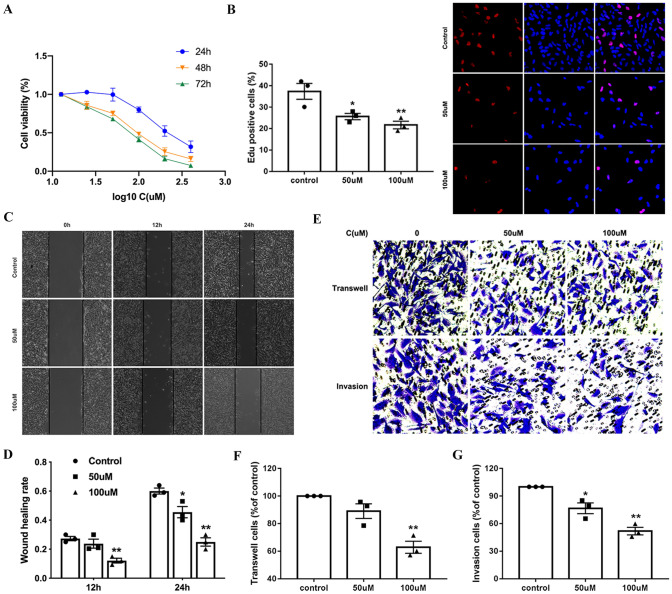

Cathepsin inhibitor 1 reduced proliferation and invasion of U251 cells

To evaluate the cytotoxic effect of cathepsin inhibitor 1 to GBM, U251 cells were seed in 96-well plates and treated with different concentration of BCA for24, 48 and 72 h, and cell viability was measured using the CCK-8. As shown in Fig. 4A, cell viability decreased following treatment with cathepsin inhibitor 1 in a concentration-dependent manner. In addition, the Edu assay was performed to determine the effect of cathepsin inhibitor 1 on GBM cell proliferation. cathepsin inhibitor 1 treatment significantly increased the percentage of Edu-positive cells compared with the control (Fig. 4B). Taken together, these data indicated that cathepsin inhibitor 1 inhibited the growth of U251 cells in a concentration-dependent manner. To evaluate the effects of cathepsin inhibitor 1 on GBM cells migration, we performed wound healing assay. For this experiment, U251 cells were cultured and then co-incubated with different doses (0, 50 and 100 μM) of CTSL-1for various time intervals (0, 12 and 24 h). Treatment with various doses of cathepsin inhibitor 1 for 12 and 24 h significantly decreased cell migration rates in U251 cells (Fig. 4C, D). We also examined cell migration and invasion capacity using a transwell chambers system after the indicated cell lines were treated with different doses (0, 50 and 100 μM) of CTSL-1 (Fig. 4E, F, G). U251 cells significantly decreased migration and invasion rates significantly in a dose-dependent manner, which was consistent with the cell wound healing assay. These results showed that cathepsin inhibitor 1 inhibits U251 cell migration and invasion in vitro.

Fig. 4.

Cathepsin inhibitor 1 inhibited the proliferation, migration, and invasion of U251 cells. A U251 cells were treated with various concentrations BCA for 24, 48 and 72 h. Cell proliferation was measured by CCK8 assay. B Cellular proliferation was measured via an Edu assay. C Wound healing assay shows the migrated cells at 0, 12 and 24 h after treatment with CTSL-1 (0, 50 and 100 μM). D Quantification of the wound healing rate in A after treatment with BCA. E After treatment, transwell assay showed that the migration and invasion cells at 24 h. F, G Quantification of the migration and invasion cells. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 for Student’s t test

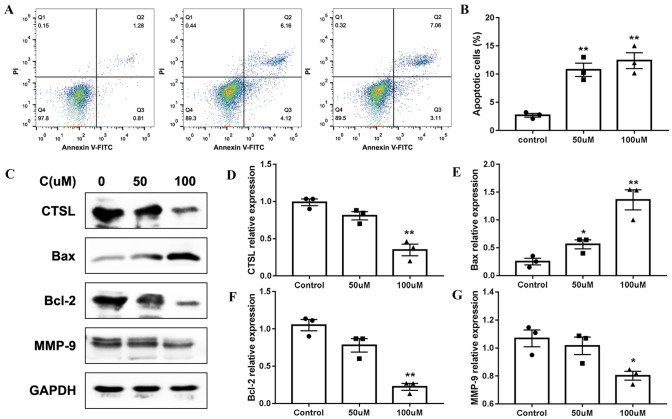

Cathepsin inhibitor 1 induced apoptosis of U251 cells

To verify whether CTSL-1 induced proliferation in an apoptosis-related manner, the effect of cathepsin inhibitor 1 on the apoptosis of U251 cells was examined using flow cytometry. We found that cathepsin inhibitor 1 treatment significantly increased the apoptosis of U251 cells (Fig. 5A, B). Meanwhile, we further detect molecular markers related to apoptosis. After treatment of cathepsin inhibitor 1, the expression of CTSL and anti-apoptosis protein BCL-2 expression markedly decrease, and pro-apoptosis protein Bax expression increase (Fig. 5C–G). Thus, these findings show that cytotoxic effects of cathepsin inhibitor 1 on U251 cells were partly caused by activation mitochondria-mediated intrinsic apoptotic pathway.

Fig. 5.

Cathepsin inhibitor 1 promoted the apoptosis of U251 cells. A The apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry after treatment with 0, 50 and 100 μM cathepsin inhibitor 1. B The percentage of cell apoptosis ratio in A. C Western blot analysis CTSL, MMP-9 Bax and Bcl-2 expression in U251 cells treated with 0, 50 and 100 μM cathepsin inhibitor 1. D–G Analysis of relative expression levels of CTSL, MMP-9 Bax and Bcl-2 in F *P < 0.05 vs. Control group, **P < 0.01 vs. Control group

Discussion

In December 2019, a novel coronavirus (2019-nCov) has caused large-scale pandemics, which has caused a severe challenge for public health and the economy (Xie and Chen 2020). A large number of studies have described the mechanism by which the SARS-CoV-2 virus enters the cell. Although, it has been widely reported that SARS-CoV2 promotes its entry into host cells through the spike protein that binds to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) membrane-bound protein (Chen et al. 2020). CTSL seems to be responsible for the cleavage of S protein under different circumstances (Vargas-Alarcón et al. 2020). Therefore, understanding the regulation of viral entry in a comorbid state will also require understanding the expression of these genes. In this study, we analysis the CTSL mRNA level of GBM in GEPIA and TCGA database. We evaluated the relationship between the expression of CTSL and the prognosis of GBM patients who susceptibility to COVID-19. In addition, TIMER database was also used to analyze the correlation between CTSL and immune infiltration in GBM. Moreover, we used CTSL inhibitor to observe the effect on the proliferation, invasion, and apoptosis of GBM cells.

Recently studies demonstrated that cancer patients are confirmed to have a higher incidence of COVID-19, more severe symptoms and has a poor prognosis (Jacobo et al. 2020). SARS-CoV-2 can undergo endocytosis, endosomal maturation followed by cleavage with pH-dependent cysteine protease CTSL to promote SARS-CoV-2 entry in cells. Recently study demonstrated that the down-regulation expression CTSL may be a potential mechanism that might reduce the ability of the virus to enter host cell, and regulation lysosome PH that would further interfere with proteolytic Spike protein activation may offer protection from the virus to enter (Kwan et al. 2021). So, CTSL plays a vital role in SARS-CoV-2 to enter cells. Here, our data demonstrated that CTSL upregulates in the GBM. In addition, SARS-CoV-2 might invade the CNS, causing neurological disorders. There is currently no effective targeted drug to treat COVID-19. Although several countries have made great progress in researching COVID-19 vaccines, the vaccines are only effective for some person. A large number of studies have shown that some small molecule drugs have a good effect on the treatment of COVID-19, for example, melatonin (Zhou et al. 2020), hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine (Sanders et al. 2020). The main mechanism of these small molecule drugs is to inhibit virus entry by targeting the endocytic pathway (Merad and Martin 2020). Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine increase the pH of the endosome, thereby inhibiting membrane fusion, which is a necessary mechanism for the virus to enter the cell (Savarino et al. 2006). In addition, the glycosylation of ACE2 and S protein can be inhibited to inhibit virus infection of cells.

Cancer is a disorder with immune dysfunction, and cancer patients are more susceptible to infections (Wang and Zhang 2020). Both humoral and cellular immunity are involved in the resistance to SARS-CoV-2 infection in the body. There is evidence that the abnormal regulation of immune response, especially T cells, may be highly related to the pathological process of COVID-19 (Qin et al. 2020). At the same time, others have also proved that abnormal and excessive immune cells (such as monocytes and macrophages) play a role in immune damage in COVID-19 (Merad and Martin 2020). We used the TIMER database to further explore its correlation with immune cell infiltration. The result showed that CTSL was very negatively correlated with purity, B cell and CD8+ T cell. However, the expression of CTSL was positively correlated with the level of immune infiltration of dendritic cell neutrophil and dendritic cell in GBM.

In addition, Kaplan–Meier curves and the log-rank test result showed that down regulation of CTSL had a favorable prognosis in GBM patients. Therefore, we evaluated the prognosis of GBM infected with SARS-CoV-2 according to the expression level of CTSL. Previous studies have found that CTSL highly expressed not only in gliomas but also in a variety of tumors, such as lung cancer, gastric cancer, ovarian cancer, breast cancer and other malignant tumors. So, cancer patients may be more susceptible to the SARS-CoV-2 infectious disease.

Previous studies have showed that CTSL expression is associated with the prognosis of tumor patients. For example, CTSL is over expression in nasopharyngeal carcinoma, breast cancer and pediatric acute myeloid leukemia, and is associated with poor disease-free survival (Yao et al. 2018; Sigloch et al. 2017). In this study, Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed that patients with high CTSL levels had shorter OS and worse prognosis. Interestingly, evidence indicates that CTSL expression may be linked to the grade and stages of endometrial cancer patients. In addition, CTSL ablation can block angiogenesis in breast cancer by affecting cell cycle-associated genes, including cyclin D1-D3, E2, A2, B2 and H (Wang et al. 2019). Wang et al. (2016) demonstrated that Knockdown of Cathepsin L can inhibit GSC growth and increase tumor radio-sensitivity by decreasing CD133 expression and decrease DNA repair checkpoint proteins (ATM and DNA-PKcs). Qin et al. (2016) demonstrated that CTSL can promote proliferation of breast cancer and downregulation of CTSL significantly inhibited the proliferation of MCF-7 cells. Moreover, CTSL can inhibited A549 and MCF-7 cells migration by regulating PI3K-AKT and Wnt signaling pathways.

Importantly, evidence indicates that CTSL proteolytic activity is significantly higher in tumor tissue compared to normal tissue. In normal tissues, the extracellular matrix is protected by endogenous cathepsin inhibitors (such as cysteine and stefins) from undesirable proteolytic activity. However, studies have shown that the expression of these CTSL inhibitors declines sharply in various tumors and CTSL proteolytic activity increase. Therefore, the use of some exogenous CTSL inhibitors can reduce the expression and proteolytic activity of CTSL. For example, CTSL inhibitor KGP94 have anti-angiogenic efficacy, and can inhibited angiogenesis of breast cancer (Sudhan et al. 2016). Sudhan et al. (2016) found that KGP94 treatment significantly attenuation of tumor cell invasion and migration that it may have significant utility as an anti-metastatic agent. This study has found that CTSL inhibitor 1 significantly reduced the growth, invasion, and migration of U251 cells in vitro and triggered mitochondrial apoptosis. Taken together, these findings suggest CTSL as a promising therapeutic target for clinical therapy in GBM patients. Therefore, because CTSL plays an important role in the pathogenesis of COVID-19, the targeted inhibition of CTSL may be an effective treatment option for this infectious disease.

In conclusion, higher expression of CTSL was found in GBM tissues compared with that of normal brain tissues, which resulted in significantly a poor survival rate in GBM patients. We considered the possible role of CTSL in the pathogenesis of COVID-19. Therefore, assessment of CTSL gene expression can be used to predict the prognosis and susceptibility to COVID-19 in these patient groups. CTSL inhibitors may be considered as promising treatments for GBM patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81960541/82060455), the Natural Science Foundation of Gansu Province (18JR3RA309 /18JR3RA365/20JR10RA741/20JR10RA766/21JR7RA426), the Science and Technology Research Project of Gansu Province (145RTSA012 and 17JR5RA307), the Project of Healty and Famliy Planing Commission of Gansu (GSWSKY-2014-31/GSWSKY-2015-58/GSWSKY2018-01), the Lanzhou Science and Technology Bureau Project (2018-1-109), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central University (lzujbky-2021-kb33), the Cuiying Science and Technology fund (CY2017-MS12/CY2017-MS15/CY2017-BJ15/CYXZ-01), Cuiying Graduate Supervisor Applicant Training Program (201803) and Special fund project for doctoral training (YJS-BD-13) of Lanzhou University Second Hospital.

Author contributions

YP, GY and QD conceived the project. QD, QL, LD, HY, BW and LN performed the experiments. QD, QL, HW, YY, HZ and LN analyzed the data. QD, GY, QL, YY, BW and LD interpreted the data and revised the manuscript. YP, GY, QL, HW and QD wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethics statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of the Lanzhou university Second hospital.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Qiang Dong and Qiao Li contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Guoqiang Yuan, Email: yuangq08@lzu.edu.cn.

Yawen Pan, Email: panyw2018@163.com.

References

- Achar A, Ghosh C. COVID-19-associated neurological disorders: the potential route of cns invasion and blood–brain barrier relevance. Cells. 2020;9(11):2360. doi: 10.3390/cells9112360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addeo A, Friedlaender A. Cancer and COVID-19: unmasking their ties. Cancer Treat Rev. 2020;88:102041. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao R, Hernandez K, Huang L, Luke JJ. ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression by clinical, HLA, immune, and microbial correlates across 34 human cancers and matched normal tissues: implications for SARS-COV-2 COVID-19. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(2):e001020. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady CP, Brinkworth RI, Dalton JP, Dowd AJ, Verity CK, Brindley PJ. Molecular modeling and substrate specificity of discrete cruzipain-like and cathepsin L-like cysteine proteinases of the human blood fluke Schistosoma mansoni. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;380(1):46–55. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Zou J, Han P, Han Z. Single-cell RNA-seq data analysis on the receptor ACE2 expression reveals the potential risk of different human organs vulnerable to 2019-nCoV infection. Front Med. 2020;14(2):185–192. doi: 10.1007/s11684-020-0789-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X, Lin D, Zhang X, Shen X, Yang Z, Yang L, et al. Profiles of immune-related genes and immune cell infiltration in the tumor microenvironment of diffuse lower-grade gliomas. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235(10):7321–7331. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemmati D, Bramanti B, Serino ML, Secchiero P, Zauli G, Tisato V. COVID-19 and individual genetic susceptibility/receptivity: role of ACE1/ACE2 genes, immunity, inflammation and coagulation. Might the double X-chromosome in females be protective against SARS-CoV-2 compared to the single X-chromosome in males? Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(10):3474. doi: 10.3390/ijms21103474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Phlmann S. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y, Zhao J, Martin W, Kallianpur A, Cheng F. New insights into genetic susceptibility of COVID-19: an ACE2 and TMPRSS2 polymorphism analysis. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):216. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01673-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobo R, Pangua C, Serrano-Montero G, Obispo B, Lara MN. COVID-19 and lung cancer: a greater fatality rate? Lung Cancer. 2020;146:19–22. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan J, Lin LT, Bell R, Bruce JP, Liu FF. Elevation in viral entry genes and innate immunity compromise underlying increased infectivity and severity of COVID-19 in cancer patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):4533. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-83366-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leskowitz S, Phillipino L, Hendrick G, Graham JB. Immune response in patients with cancer. Cancer. 2015;10(6):1103–1105. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195711/12)10:6<1103::AID-CNCR2820100602>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merad M, Martin JC. Pathological inflammation in patients with COVID-19: a key role for monocytes and macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(6):1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0331-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T. Cathepsin L: critical role in Ii degradation and CD4 T cell selection in the thymus. Science. 1998;280(5362):450–453. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5362.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanappa A, Chastain WH, Paz M, Solch RJ, Bix G. SARS-CoV-2 mediated neuroinflammation and the impact of COVID-19 in neurological disorders. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2021;58(3):1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2021.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin G, Cai Y, Long J, Zeng H, Xu W, Li Y, Liu M, Zhang H, He ZL, Chen WG. Cathepsin L is involved in proliferation and invasion of breast cancer cells. Neoplasma. 2016;63(1):30–36. doi: 10.4149/neo_2016_004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C, Zhou L, Hu Z, Zhang S, Tian DS. Dysregulation of immune response in patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):762–768. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ, Cutrell JB. Pharmacologic treatments for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323(18):1824–1836. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savarino A, Trani LD, Donatelli I, Cauda R, Cassone A. New insights into the antiviral effects of chloroquine. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6(2):67–69. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70361-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan Y, Yu Y, Wen Z, Wei Y, Liu T. FOXO3a promotes gastric cancer cell migration and invasion through the induction of cathepsin L. Oncotarget. 2016;7(23):34773–34784. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigloch FC, Tholen M, Gomez-Auli A, Biniossek ML, Reinheckel T, Schilling O. Proteomic analysis of lung metastases in a murine breast cancer model reveals divergent influence of CTSB and CTSL overexpression. J Cancer. 2017;8(19):4065–4074. doi: 10.7150/jca.21401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhan DR, Siemann DW. Cathepsin L inhibition by the small molecule KGP94 suppresses tumor microenvironment enhanced metastasis associated cell functions of prostate and breast cancer cells. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2013;30(7):891–902. doi: 10.1007/s10585-013-9590-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhan DR, Rabaglino MB, Wood CE, Siemann DW. Cathepsin L in tumor angiogenesis and its therapeutic intervention by the small molecule inhibitor KGP94. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2016;33(5):461–473. doi: 10.1007/s10585-016-9790-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Alarcón G, Posadas-Sánchez R, Ramírez-Bello J. Variability in genes related to SARS-CoV-2 entry into host cells (ACE2, TMPRSS2, TMPRSS11A, ELANE, and CTSL) and its potential use in association studies. Life Sci. 2020;260:118313. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Zhang L. Risk of COVID-19 for patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(4):e180. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30149-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Long LM, Wang L, Tan C, Feng X, Chen X, Liang Z. Knockdown of Cathepsin L promotes radiosensitivity of glioma stem cells both in vivo and in vitro. Cancer Lett. 2016;371(2):274–284. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Xiang Z, Zhu T, Chen J, Zhou W. Cathepsin L interacts with CDK2AP1 as a potential predictor of prognosis in patients with breast cancer. Oncol Lett. 2019;19(1):167–176. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.11067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie M, Chen Q. Insight into 2019 novel coronavirus—an updated intrim review and lessons from SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao F, Xiong Y, Xiao S, Zhao Y, Ying Z, Long W, et al. Cathepsin L promotes ionizing radiation-induced U251 glioma cell migration and invasion through regulating the GSK-3β/CUX1 pathway. Cell Signal. 2018;44:62. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Hou Y, Shen J, Huang Y, Cheng F. Network-based drug repurposing for novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV/SARS-CoV-2. Cell Discov. 2020;16(6):14. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0153-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.