Abstract

Objective

To design and implement a health system level intervention to reduce escalating multiple sclerosis (MS) disease modifying treatment (DMT) expenditures and improve outcomes.

Methods

We conducted stakeholder meetings, reviewed pharmacy utilization data, and abstracted information in subsets of persons with MS (pwMS) from the electronic health record to identify gaps in, and barriers to improving, quality, and affordability of MS care in Kaiser Permanente Southern California. These results informed the development and implementation of the MS Treatment Optimization Program (MSTOP).

Results

The two main gaps identified were under‐prescribing of highly effective DMTs (HET, 4.9%) and the preferred formulary DMT (20.9%) among DMT‐treated pwMS. The main barriers identified were prescribers’ fear of rare but serious HET side effects, lack of MS‐specific and health systems science knowledge, Pharma influence, evidence gaps, formulary decisions‐based solely on costs, and multidirectional mistrust between neurologists, practice leaders, and health plan pharmacists. To overcome these barriers MSTOP developed four strategies: (1) risk‐stratified treatment algorithm to increase use of HETs; (2) an expert‐led ethical, cost‐sensitive, risk‐stratified, preferred formulary; (3) proactive counter‐launch campaigns to minimize uptake of new, low‐value DMTs; and (4) discontinuation of ineffective DMTs in progressive, non‐relapsing MS. The multicomponent MSTOP was implemented through education, training, and expanding access to MS‐trained providers, audit and feedback, and continual evidence reviews.

Interpretation

The causes of wasteful spending on MS DMTs are complex and require multiple strategies to resolve. We provide herein granular details of how we designed and implemented our health system intervention to facilitate its adaption to other settings and conditions.

Introduction

The prevailing approach to multiple sclerosis (MS) treatment in the United States (US) over the past two decades has led to an exponential increase in societal MS treatment expenditures and a sevenfold increase in patient out‐of‐pocket expenses, without convincing evidence of improved outcomes. 1 The unaffordable prices of MS disease modifying treatments (DMTs) also increase inequities by forcing some persons with MS (pwMS) who would benefit from DMTs to go un‐ or undertreated. In addition to Pharma's unregulated ability to set and increase drug prices, nonevidence‐based prescribing practices contribute to these increasing MS DMTs expenditures and its’ societal consequences.

Medicare spent an estimated 4.4 billion on interferon‐betas, glatiramer acetate, teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate, and fingolimod in 2016 alone. 2 What is particularly troubling is that these expenditures are unlikely to have improved outcomes as the majority of Medicare recipients are 65 years of age or older. At these ages, several observational studies have found no benefit of treatment with these DMTs, 3 , 4 , 5 and randomized controlled trial (RCT) data to suggest otherwise do not exist. 6

Recognizing that the prevailing US approach was ineffective, unaffordable, and inequitable, we developed and implemented a multicomponent health system level intervention, the MS Treatment Optimization Program (MSTOP). We provide herein the details of how MSTOP was developed, its goals and strategies, and the tactics employed to successfully implement it. MSTOP has been implemented in Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) and spread to other KP regions. The reduction of MS relapses and significant reduction in MS DMT spending resulting from the successful implementation of MSTOP will be detailed in another manuscript. 7

Methods

We reviewed meeting minutes, drug utilization reports, calendars, and draft documents to describe the staggered development and implementation of the MS Treatment Optimization Program.

Setting

KPSC is a large prepaid health care organization that provides comprehensive health care to over 4.7 million members. KPSC uses a comprehensive electronic health record (EHR) system which includes all inpatient and outpatient encounters, laboratory and imaging tests, diagnoses, medications, and demographic characteristics. Permanente medical groups have a strong physician‐leadership culture and routinely partners with Kaiser Foundation Hospitals and Health Plan, including the health plan's pharmacy team. MS care is provided at 16 medical centers by over 200 neurologists. Care is provided to approximately 5000 pwMS annually. Physician interaction with pharmaceutical manufacturers requires prior justification and approval; gifts, honoraria, and travel are not permissible, and meals are limited to <$25. Neurology practice leaders from each medical center meet quarterly. It is mandatory that this group set specific, measurable annual quality goals––goals that require approval from senior leadership.

Gap assessments

Gaps in MS care assessments beginning in 2009 included review of MS DMT prescribing and cost data, and full EHR review in selected subgroups, following senior leadership's decision (MHK) to hire an MS clinician‐researcher (ALG). Prescribing data were obtained from the complete EHR and included the proportion of pwMS on a specific DMT or group of DMTs among all pwMS on any DMTs and annual proportion of pwMS switching among modestly effective DMTs (meDMTs). DMT use was defined as at least one dispensed MS DMT during the calendar year. Patients who switched from a meDMT to a highly effective DMT (HET) in the same calendar year were counted as being on HET during that year to incentivize this desired change. Because natalizumab and rituximab are not MS‐specific drugs, only persons with at least one MS ICD9 code and where the prescribing provider was a neurology provider were included.

Whether a pwMS on a DMT had been provided with a walker, wheelchair, hospital bed, or Hoyer lift during their membership was obtained from the EHR. The full EHR was abstracted by an MS specialist (ALG) to determine whether those pwMS on natalizumab had relapsing or progressive, non‐relapsing forms of MS. Low value was defined as a DMT whose negotiated contracting price exceeded the $150,000 cost per quality of life year gained threshold. 2 , 8

Identifying barriers, stakeholder engagement, and establishing key programmatic goals and strategies

Discussions to identify barriers in delivering higher quality and more affordable MS care with neurology and senior practice leaders were conducted primarily during times when these groups met regularly. Feedback from general neurologists to identify barriers were obtained during MS‐specific education sessions and through academic detailing (peer‐to‐peer educational outreach adapted from pharmaceutical detailing) 9 led by an MS expert (ALG). Health plan pharmacists were engaged during MS‐specific meetings. These methods were simultaneously used to obtain leadership, neurologists’, and health plan pharmacists’ support for key programmatic goals and strategies as they were developed and implemented.

Classifying MS DMTs as highly or modestly effective

We developed evidence‐based criteria for classifying DMTs by efficacy on clinical outcomes (e.g., relapses and disability progression) in relapsing forms of MS described in detail elsewhere. 10 Briefly, HETs are those that have demonstrated evidence of superiority to an active comparator in at least one head‐to‐head RCT and/or evidence of potency defined as a large magnitude of effect in an RCT conducted in a population with highly active relapsing MS or a positive RCT conducted in pwMS who relapsed on modestly effective DMTs. In 2010, three HET products (natalizumab, rituximab, and fingolimod) and five meDMT products (four interferon‐betas and one glatiramer acetate) were available for use.

Results

Gaps

Under‐prescribing of HETs

In 2009, only 4.9% (n = 107) of pwMS with at least one prescription for any DMT (n = 2313) were prescribed an HET, the majority of whom were treated with natalizumab (n = 96). Chart review of these natalizumab‐treated pwMS revealed that 32 (33.3%) pwMS had progressive, inactive forms of MS who had continued to decline on other DMTs––a subtype of MS in which natalizumab had not demonstrated efficacy. 8

Poor adherence to preferred formulary DMT

Pharmacy and neurology practice leaders agreed to make the lowest‐priced interferon‐beta or glatiramer acetate product the preferred meDMT for pwMS first starting a DMT in 2010. In addition, the lowest priced interferon‐beta product was endorsed as the preferred interferon‐beta. It was recommended that pwMS on higher priced interferon‐beta products be converted to the preferred interferon‐beta, with the exception of those who were previously unable to tolerate the preferred interferon‐beta. This strategy had been successfully implemented in another Kaiser region. 11 Despite these agreed upon recommendations, use of the preferred interferon‐beta product remained low at 20.9% in 2010 and 20.1% in 2011 among all prescribed DMTs. For pwMS starting their first DMT, use of the preferred interferon‐beta product rose from 25% (n = 68) in 2010 to 39% (n = 103) in 2011. Among pwMS prescribed an interferon‐beta product, use of non‐preferred agents remained high at 65.7% in 2010 and 65.2% in 2011.

Use of ineffective DMTs in persons with advanced MS disability

In addition to the use of natalizumab in inactive, progressive forms of MS, DMT utilization review from 2012 showed that DMTs proven ineffective in progressive, non‐relapsing forms of MS 8 were being prescribed in 61.8% (n = 107) of DMT‐treated pwMS ≥65 years of age who required a walker, wheelchair, hospital bed, and/or Hoyer lift.

Barriers

Discussions with physicians, pharmacy leaders, and neurologists revealed multiple barriers (Table 1), including significant knowledge gaps, Pharma influence, inadequate visit lengths and support staff, and mistrust.

Table 1.

Main barriers to rational MS DMT use.

| MS knowledge gaps |

| Unfamiliar with the MS prognostic literature |

| Unaware of large differences in DMT costs and expected inflation |

| Unaware that many DMTs had been tested head‐to‐head in RCTs |

| Uncomfortable with rare SAEs and complex monitoring and risk mitigation strategies for HETs |

| Unfamiliar with negative RCT results in progressive, non‐relapsing forms of MS |

| Uncomfortable having DMT stopping conversation in pwMS with advanced disease |

| Pharma influence |

| Health systems science knowledge gaps |

| Some clinicians believed cost should not enter into clinical decision‐making |

| Some clinicians unaware of how expensive drugs get paid for |

| Continuing education |

| No clear path for continuing MS education in‐line with organizational values |

| Inadvertent barriers to physicians’ participation in professional society meetings |

| Inadequate visit length and support |

| Visit length too short to deliver increasing complex MS care |

| Lack of support staff to assist with patient management |

| Inadequate visit length to have DMT stopping conversation |

| Mistrust |

| Bidirectional mistrust between health plan pharmacists and clinicians |

Abbreviations: MS, multiple sclerosis; DMT, disease modifying treatment; HET, highly effective DMT; meDMT, modestly effective DMT, RCT, randomized controlled trial; SAE, serious adverse events; pwMS, person(s) with MS.

MS and health systems science knowledge gaps

The knowledge gaps were both MS‐specific and pertained to health systems science. MS‐specific knowledge gaps included no or superficial understanding of MS DMT RCT results, particularly those comparing DMTs head‐to‐head or in progressive forms of MS among clinicians, and lack of knowledge of MS prognostic literature among both clinicians and pharmacists. Manual chart reviews also revealed confusion about MS subtypes (e.g., benign vs. relapsing vs. progressive forms of MS).

Stakeholders at all levels also had surprisingly low grasp of health systems science, in particular, how expensive medications get paid for on a societal health plan or at times even on an individual level. Some clinicians expressed discomfort considering the cost of a medication when treating patients and disagreed that clinicians should act as responsible stewards of their patients’ limited health care dollars. In other instances, the main issue was that the large differences in drug prices and expected inflation were not communicated to the prescribing clinicians.

Pharma and barriers to continuing education

General neurologists who were interested in learning about MS DMTs got their information primarily from local Pharma‐sponsored dinner talks. Further discussions with practice leaders and neurologists revealed multiple barriers to obtaining non‐Pharma‐influenced education. Very few clinicians attended professional society meetings, citing expense, and time away from clinic as barriers. Even when they did attend professional society meetings, clinicians reported that MS teaching courses and platform presentations were usually heavily Pharma‐influenced or too specialized to be useful in their practice. On a health system level, there was no plan for how to assure continuing education for clinicians in‐line with organizational values. New drug education was provided in‐person by health plan pharmacists to neurology practice leaders typically 6–12 months after FDA approval of new drugs. This education relied primarily on the package insert; full review of FDA documents was not part of the pharmacy group's workflow. Little attempt was made to educate the prescribing clinicians aside from email distribution of lengthy pharmacy documents.

Visit lengths and inadequate support

After conducting educational sessions to fill in MS‐specific and health systems science gaps, general neurologists were still reluctant to treat pwMS with HET or to discontinue ineffective DMTs. They continued to feel uncomfortable with the rare but serious adverse events (SAE) associated with natalizumab, fingolimod, and rituximab. While the majority of these SAEs can be prevented through laboratory monitoring, dose adjustments and/or use of prophylactic antivirals, the general neurologists noted complicated protocols, competing incentives to see patients rather than provide non‐billable care, and lack of support staff who could assist with these functions as barriers. Inadequate visit length was also a barrier to neurologists’ ability to discontinue ineffective DMTs in progressive, non‐relapsing pwMS.

Mistrust

Substantial bidirectional mistrust between general neurologists and health plan pharmacists was another key barrier to rational use of MS DMTs. This mistrust undermined the health plan's initial attempts to prioritize prescribing of the lowest‐priced meDMT. The pharmacists were dismayed that the neurologists were unfamiliar with the results of MS DMT RCTs and that they continued to prescribe the more expensive DMTs even when a lower priced DMT equivalent in efficacy, safety, and mechanism of action was available. The neurologists in turn were annoyed by the frequent requests to prescribe differently across multiple indications. They noted that the MS step therapy recommendations developed by pharmacists lacked clinical context and assigned preference to the lowest cost DMT, which often changed as contracts were re‐negotiated. Some neurologists voiced concerns that “all they [health plan pharmacists and practice leaders] care about is money.” Additional mistrust between neurologists and practice leaders was driven by clinicians’ frustrations of being asked to provide increasingly complex care in the same amount of time without additional support.

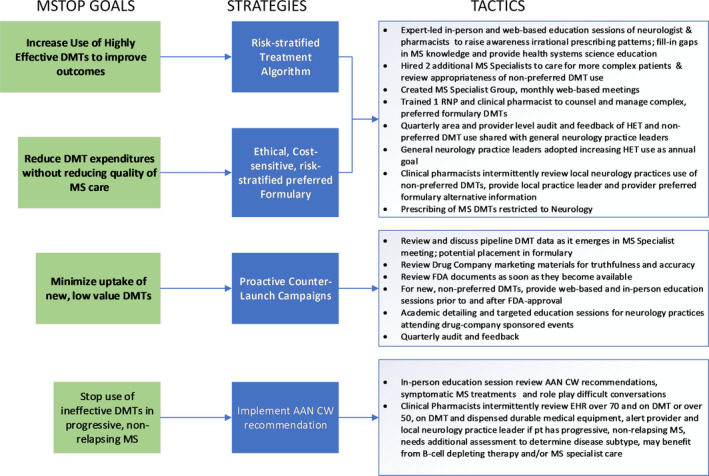

Programmatic goals, strategies, and tactics

The goals, in order of priority, strategies and tactics employed to accomplish these goals are depicted in Figure 1. To maximize rapid implementation of MSTOP it was important that the goals be easily measurable. We chose focusing on increasing HET use as the principal goal for MSTOP because it was likely to have the biggest impact on MS outcomes and, at worst, would not affect MS DMT expenditures as all DMTs are expensive and subject to similar annual inflation. We also reasoned that focusing on quality rather than affordability would improve trust between clinicians and pharmacists, and that without this trust, layering‐in of subsequent initiatives focused primarily on affordability would continue to be unsuccessful.

Figure 1.

MSTOP Design. Depicted are the goals of the multiple sclerosis (MS) treatment optimization program (MSTOP), in order of priority and timing of implementation and the strategies and tactics employed to accomplish these goals. The principal goals of increasing the use of highly effective DMTs (HET) and reducing DMT expenditures without adversely affecting the quality of MS care were accomplished by first creating a treatment algorithm that recommends use of HET in persons with MS (pwMS) judged to be at high risk of long‐term disability and defining a preferred formulary that is, similarly risk‐ stratified and recommends the lowest cost DMT when efficacy and safety are equivalent. Once these strategies were defined, they were socialized and endorsed by practice leaders, additional MS specialists were hired, and support staff trained to aide in implementation. The primary strategy to minimize prescribing of new low‐value DMTs was the development and implementation of proactive counter‐launch campaigns. To de‐implement prescribing of ineffective DMTs in pwMS with advanced disability, implementation of American Academy of Neurology's (AAN) Choosing Wisely recommendation was accomplished by having clinical pharmacists provide extensive support identifying potential discontinuation candidates and MS specialists to assist with DMT discontinuations.

To measure MSTOP implementation progress, the pharmacy team generated quarterly reports of HET use, use of non‐preferred DMTs, and use of new low‐value DMTs among those pwMS on any DMT stratified by medical center. This information was shared at the quarterly neurology practice leaders meeting and used to identify medical centers that led or lagged in implementation. Once a lagging area was identified, additional barrier assessments, and targeted interventions were conducted to inform improved MSTOP implementation.

Risk‐stratified treatment algorithm and expert‐led preferred formulary

The primary strategy to increase the use of HET was the creation of a risk‐stratified MS treatment algorithm described in detail elsewhere. 10 Briefly, the algorithm helps clinicians judge when the risk of intermediate or long‐term disability from relapsing forms of MS outweighs the rare, but serious side effects of the preferred HETs, natalizumab or rituximab. The algorithm is based on the best available evidence, and when the evidence is weak or absent, consensus. Persons with relapsing forms of MS are stratified as high‐, intermediate‐ or low‐risk of long‐term disability based on clinical characteristics readily available in routine clinical practice. The algorithm initially recommended starting or switching to HETs for those at high‐risk; meDMT for those at intermediate‐risk; and meDMT or watchful waiting in those at low‐risk of long‐term disability. Implementation began in 2012. To accommodate pwMS with cost or other barriers to DMT use, the MS specialist group added the options of standard induction or brief induction (≤1 year) with an affordable B‐cell depleting agent in the intermediate‐ and low‐risk groups, respectively in 2019.

The primary strategy to reduce expenditures on MS DMTs without reducing quality of MS care was the development of an ethical, cost‐sensitive preferred formulary led by MS experts. This preferred formulary prioritizes the safest DMTs within the HET or meDMT groups, and the lowest cost within group DMT when efficacy and safety profiles are similar. 10 Preferred HETs were natalizumab, rituximab, fingolimod and preferred meDMTs, the lowest‐priced Interferon‐beta and/or glatiramer acetate product when it was launched in 2013. Dimethyl fumarate and teriflunomide have inferior safety profiles, yet similar efficacy to glatiramer acetate or interferon‐betas, and therefore were classified as non‐preferred meDMTs. 10 If a patient cannot tolerate the preferred formulary DMT or take it as prescribed for other reasons, switching to another DMT, including non‐preferred DMTs as appropriate, is strongly recommended. This recommended formulary contrasts with the health plan's unpopular and unsuccessful approach of requiring that the lowest cost DMT be used preferentially, regardless of its efficacy or safety or a pwMS underlying risk of disability.

Education

Because lack of knowledge was a key barrier, education and academic detailing were implemented by MS experts who partnered with health plan pharmacists targeting physician leaders, neurologists, and clinical pharmacists. Education encompassed not only MS‐specific knowledge, but also how drug pricing and pharma advertising affect health care and patient out‐of‐pocket expenses. This included a one‐day in‐person education and training session for neurologists in 2013. While this increased general neurologists’ awareness of the gaps in MS care, importance of considering costs and their support of the overarching MSTOP approach, they remained reluctant to prescribe or manage pwMS on HET or to stop DMTs in persons with advanced MS‐related disability, preferring to refer such patients to an MS specialist instead.

MS specialists and clinical pharmacists

Quarterly pharmacy reports showed that uptake in the use of HET, despite education and academic detailing, was slow and primarily being implemented by the MS clinician‐researcher and the RNP she had trained. Hiring of the clinician‐researcher's former MS fellow in late 2013 as a general neurologist and the existence of another MS fellowship‐trained neurologist prior to 2010 did not result in significant overall increase in HET use. In accordance with their roles as general neurologists, pwMS were not preferentially assigned to their schedules and they cared only for the members of their medical center. As such, the relatively low volume of MS patients and lack of incentives had led the older MS‐trained neurologist to feel uncomfortable serving as an MS expert by 2010. These findings supported the business case to create a health system‐wide MS Specialist group.

The creation of the MS Specialists Group required changing hiring practices and referral patterns accomplished through ongoing stakeholder meetings with senior practice and neurology leaders. Two additional full‐time MS specialists were hired in 2015, both with evidence‐based medicine training. During the interviewing and hiring process, the expectation that they provide care exclusively to MS and other neuroimmunology patients and implement MSTOP was explicitly stated. These MS specialists were assigned to provide preferential access to MS and other neuroimmunology patients, from four medical centers per specialist for a patient panel size of approximately 1000 patients per MS specialist, and rarely provide general neurology care. Visit length was extended for these MS specialists from 45 up to 60 min for a new consult and from 15 up to 40 min for follow‐up care. The visit length for follow‐ups is determined by the complexity of care the pwMS requires; 30 min is the most common visit length, with 40 min reserved for those pwMS with advanced disability that require botulinum toxin injections to control spasticity.

As the evidence‐base for MS care is rapidly evolving, a regular MS specialists meeting was requested and approved by neurology leaders. This MS specialist group meets monthly for 1 h during their regularly scheduled clinic time, in lieu of seeing patients, to review data, develop, and update best practice recommendations. 10

Initially some neurology practice leaders resisted referring pwMS to the MS specialists and expressed concerns about meeting general neurology access requirements should the MS specialist at their center see pwMS from other medical centers. Senior leadership's (MHK) insistence that the neurology practice leaders adopt increasing HET use as their annual quality goal was instrumental in changing these referral patterns.

Additional support staff, primarily local clinical pharmacists, to assist with the implementation of safety monitoring and dose‐adjustment protocols of HETs and/or conduct chart reviews of pwMS to identify those who could potentially benefit from HETs or DMT discontinuation were added in 2018. The first two clinical pharmacists were trained by the MS clinician‐researcher, who worked collaboratively to create clear treatment monitoring and chart abstraction protocols. These clinical pharmacists now lead the training and dissemination of updated information to local clinical pharmacists assigned to assist with MSTOP.

Proactive counter‐launch campaigns

At least 1 year prior to the anticipated launch of a new product, Pharma ramps up aggressive marketing campaigns that often include unsubstantiated claims of a drug's superior efficacy or safety to existing products. This information is disseminated broadly through “advisory” panel meetings. The “advisors” in turn give dinner talks and often lead education sessions at or in conjunction with professional society meetings to encourage general neurologists to prescribe the new product. Because we found that this type of Pharma influence was affecting our neurologists prescribing preferences, we created what we call proactive counter‐launch campaigns in 2013. These campaigns aim to discourage use of low‐value DMTs awaiting FDA approval and have included dimethyl fumarate, teriflunomide, pegylated interferon‐1a, siponimod, and cladribine. We employ academic detailing, education sessions, and targeted messaging to address unsubstantiated claims of a drug's superior efficacy or safety. Information is gathered from review of full FDA documents, conference proceedings, internet searches, and advertising materials in addition to the published literature. The process begins at the time of filing for FDA approval or earlier and continues for at least 1 year after approval. We reasoned that it would be more effective to minimize, rather than de‐implement, undesirable prescribing practices.

Ineffective DMTs in progressive, non‐relapsing pwMS

The incorporation of the American Academy of Neurology's (AAN) Choosing Wisely recommendation to not prescribe interferon‐betas or glatiramer acetate in progressive, non‐relapsing forms of MS was added to MSTOP in 2013 at the request of senior practice leaders. While this is strongly supported by evidence, it has been a challenging goal to measure and implement. As time constraints and lack of support were barriers to MSTOP implementation, educating general neurologists to identify these patients and conduct often lengthy and emotional discontinuation discussions were unsuccessful. Identifying such patients proved challenging. Using coding records and electronic text‐string searches alone were not helpful, as there is only one ICD code for all forms of MS, MRI reports are not standardized, and subtype designations by general neurologists were often inaccurate (e.g., relapsing progressive MS for a bed‐bound pwMS with inactive SPMS).

To overcome these barriers, clinical pharmacists were assigned part‐time by their medical centers intermittently to identify potentially eligible pwMS by reviewing the EHR of persons over the age of 50 on a DMT who had been provided a walker, wheelchair, Hoyer lift or hospital bed, or over the age of 70 and on a DMT. Upon identification of potential discontinuation (or escalation to a B‐cell depleting DMT) candidates, the pharmacists sent messages to the prescribing neurologists to inform them of their findings and request that the DMT be discontinued due to lack of effectiveness or that the pwMS be referred to an MS specialist. The general neurologists most often chose the option of referring to an MS specialist.

Targeted intervention

One large medical center lagged behind the other 15 medical centers for 4 years in MSTOP implementation. To understand why, we conducted additional barrier assessments which revealed poor attendance of in‐person education sessions and practice group meetings because of lengthy travel times (0–2 attendees of 18 neurology providers, ≥5 h travel per session); with unresolved gaps in MS and health systems science knowledge. To overcome these barriers, we conducted local education sessions and trained a full‐time clinical pharmacist to implement MSTOP. To encourage attendance, the local in‐person education sessions were conducted during the clinicians’ usual work hours, clinic schedules were blocked for 2 h on three separate occasions and were led by an MS specialist.

Attempts to hire an MS specialist for this medical center were unsuccessful. Instead, a clinical pharmacist was trained and deployed to review EHRs, apply the treatment algorithm, and assist with preferred HET infusion orders, safety monitoring, and patient counseling. Neurologists were initially hesitant to follow the advice of the clinical pharmacist and resented having to book additional patients on their already fully booked schedules. To overcome these barriers, the clinical pharmacist workflow was changed to reviewing only those charts of pwMS with upcoming appointments. The clinical pharmacist was also relocated to the neurology clinic and built trust by answering other pharmacy‐related questions. For complex cases, MS specialists increased their availability to review the EHR via electronic messaging systems and/or to provide patient consultations via video or telephone visits.

Discussion

The goals, strategies, and tactics of MSTOP were developed to address the multitude of barriers to improving MS outcomes while simultaneously reducing MS DMT expenditures. While the solution we developed is novel, the overarching challenge and barriers we faced were not. Unregulated DMT pricing and nonevidence‐based prescribing practices were resulting in marked increases in health system spending on MS DMTs. Extensive input from stakeholders revealed that mistrust stemming from lack of expertise, inadequate audit and feedback, and Pharma influence, even with KP’s strict policies, were key factors perpetuating the prescribing practices.

Unique aspects of our approach that we believe underpin its success are that clinical experts led the development and implementation of the risk‐stratified, treatment algorithm, and cost‐sensitive preferred formulary rather than administrators; that the formulary adheres to ethical principles of step therapy design 12 ; that we changed hiring and workflow practices to create a health system‐wide MS specialists group that updates and implements the treatment algorithm and preferred formulary; and that we employed Pharma advertising tactics including academic detailing and new product (counter) launch campaigns.

In contrast to our approach, most US insurers focus on reducing MS DMT expenditures by creating highly restrictive step therapy programs based primarily on opaque price negotiations. 2 Many high‐income countries have found legislative solutions to control MS DMT costs. 13 , 14 However, whether focusing on affordability and access alone improve MS outcomes has not been demonstrated. 15

These models rely on physician judgement to appropriately risk‐stratify and select DMTs. Clear and specific guidance for how to choose a DMT for a given pwMS, other than ours, have not been developed. Professional society guidelines 16 , 17 do not provide such guidance, in part due to the lack of validated instruments that accurately weighs the risk of starting an HET with the risk of poor MS outcomes in relapsing forms of MS. Neurologists in the US are accustomed to a culture that prioritizes autonomy in clinical decision‐making as opposed to standardization of practices. Even in our system that values standardization to reduce disparities, simply hiring MS specialists did not lead to meaningful increase in HET use.

Endorsement of MSTOP by practice leaders and providing neurologists with MS‐specific education were both necessary but insufficient tactics to change prescribing practices. Both tactics were important in the creation of an MS specialist group and changing patient care patterns from prioritizing access to any neurologist to prioritizing access to MS specialty care. From a management perspective, shifting the increasingly complex MS care pwMS need from general neurologists to the MS specialist group and clinical pharmacists maximizes the strengths of general neurologists (providing general neurology care) and makes their short‐comings in providing evidence‐based MS care moot.

It is important to emphasize that hiring or training MS specialty care providers is a tactic not a strategy. It was successful only after the care gaps they were expected to close and the strategies to accomplish this were agreed upon by neurologists and practice leaders. 7

A cornerstone of KP’s mission is providing affordable care. Thus, we were surprised to find that some clinicians still believed that costs should not enter into clinical decision‐making and held naïve views of how expensive drugs get paid for. This highlights the need for providing principles of value‐based prescribing, not just drug‐or field‐specific education to physicians in all stages of training and practice.

The proactive counter‐launch campaigns were designed to address the aggressive marketing of low‐value DMTs by Pharma. This strategy is novel and required the health system to change from reactive, and rather passive, to proactive and to change its’ approach to evaluating and educating prescribing clinicians about new drugs. We accomplished this primarily through changing the culture. Very little additional financial or staff resources were required to create and implement the counter‐launch campaigns. Additional financial resources consisted mainly of travel, food, and beverage reimbursement for system‐wide educational events and academic detailing.

The biggest limitation of MSTOP is whether it can be adapted to non‐KP settings. This will depend upon insurers and clinicians’ willingness to work together. Another limitation is the lack of clear guidance when to start and stop B‐cell depleting treatments in progressive forms of MS, where these treatments are less effective and less safe than in relapsing forms of MS. 2 , 8 The strengths of MSTOP are the comprehensive focus on assessing and overcoming the multitude of barriers to appropriate MS DMT use on a health system level.

We are not aware of any similarly successful health system level intervention in MS or other chronic neurological or autoimmune diseases. As such, MSTOP can be viewed not only as a model for reducing costs and improving outcomes in pwMS, but also for other diseases that could benefit from defining and standardizing rational prescribing practices. By providing the details of development and implementation of MSTOP, we aim to facilitate the adaption of this approach to other settings and conditions.

Conflict of Interest

A. Langer‐Gould receives grant support and awards from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and the National MS Society. She currently serves as a voting member on the California Technology Assessment Forum, a core program of the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER). She has received sponsored and reimbursed travel from ICER and the National Institutes of Health. S. Cheng, B. H. Li, and M. H. Kanter declare no disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

Author Contributions

A. Langer‐Gould's contributions include designing and leading implementation of the multifaceted program, data review, data analysis, drafting and revising the manuscript for content, including study concept, and interpretation of data. She has full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. S. Cheng contributed to the data collection, data analysis, and revision of the manuscript for content. B. H. Li contributed to the data collection, data analysis, interpretation of data, and revision of the manuscript for content. M. H. Kanter contributed to the study design, interpretation of data, and revision of the manuscript for content.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank M. K. Gould for helpful feedback throughout the development and implementation of MSTOP. The authors also thank B. Mittman, PhD and S. A. Klocke, PharmD, BCPS for helpful input during the development of MSTOP and J. B. Smith for help with manuscript preparation.

Funding Information

No funding information provided.

References

- 1. San‐Juan‐Rodriguez A, Good CB, Heyman RA, Parekh N, Shrank WH, Hernandez I. Trends in prices, market share, and spending on self‐administered disease‐modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis in Medicare Part D. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(11):1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) . Disease‐modifying therapies for relapsing‐remitting and primary progressive multiple sclerosis: effectiveness and value. Final Evidence Report. March 6, 2017. Accessed September 01, 2020. http://icerorg.wpengine.com/wp‐content/uploads/2020/10/CTAF_MS_Final_Report_030617.pdf

- 3. Hua LH, Fan TH, Conway D, Thompson N, Kinzy TG. Discontinuation of disease‐modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis over age 60. Mult Scler J. 2019;25(5):699‐708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yano H, Gonzalez C, Healy BC, Glanz BI, Weiner HL, Chitnis T. Discontinuation of disease‐modifying therapy for patients with relapsing‐remitting multiple sclerosis: effect on clinical and MRI outcomes. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;35:119‐127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McFaul D, Hakopian N, Smith J, Langer‐Gould A. Defining benign/burnt‐out MS and discontinuing disease‐modifying therapies. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2021;8(2):e960. 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Butler M, Forte ML, Schwehr N, Carpenter A, Kane RL. AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Decisional Dilemmas in Discontinuing Prolonged Disease‐Modifying Treatment for Multiple Sclerosis. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Langer‐Gould A, Smith J, Li B, Kanter MH. Implementation of a risk‐stratified multiple sclerosis treatment algorithm: improved quality and affordability. Neurology. 2020;94(15 Supplement):2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) . Siponimod for the treatment of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: effectiveness and value. Final Evidence Report. June 20, 2019. Accessed September 01, 2020. https://34eyj51jerf417itp82ufdoe‐wpengine.netdna‐ssl.com/wp‐content/uploads/2020/10/ICER_MS_Final_Evidence_Report_062019.pdf

- 9. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . Module 10. Academic Detailing as a Quality Improvement Tool. Content last reviewed May 2013. 2013. https://www.ahrq.gov/ncepcr/tools/pf‐handbook/mod10.html

- 10. Langer‐Gould A, Klocke S, Beaber B, et al. Improving quality, affordability, and equity of multiple sclerosis care. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2021;8(4):980‐991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hahn N, Palmer KE, Klocke S, Delate T. Therapeutic interferon interchange in relapsing multiple sclerosis lowers health care and pharmacy expenditures with comparable safety. Perm J. 2018;30(22):18‐046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nayak RK, Pearson SD. The ethics of ‘fail first’: guidelines and practical scenarios for step therapy coverage policies. Health Affairs. 2014;33(10):1779‐1785. 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Naci H, Kesselheim AS. Specialty drugs—A distinctly American phenomenon. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(23):2179‐2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Robinson JC. Lower prices and greater patient access—Lessons from Germany's drug‐purchasing structure. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(23):2177‐2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shirani A, Zhao Y, Karim ME, et al. Association between use of interferon beta and progression of disability in patients with relapsing‐remitting multiple sclerosis. JAMA. 2012;308(3):247‐256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Montalban X, Gold R, Thompson AJ, et al. ECTRIMS/EAN guideline on the pharmacological treatment of people with multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25(2):215‐237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rae‐Grant A, Day GS, Marrie RA, et al. Practice guideline recommendations summary: disease‐modifying therapies for adults with multiple sclerosis: report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2018;90(17):777‐788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]