Abstract

Two distinct diazo precursors, imidazotetrazine and nitrous amide, were explored as promoieties in designing prodrugs of 6-diazo-5-oxo-l-norleucine (DON), a glutamine antagonist. As a model for an imidazotetrazine-based prodrug, we synthesized (S)-2-acetamido-6-(8-carbamoyl-4-oxoimidazo[5,1-d][1,2,3,5]tetrazin-3(4H)-yl)-5-oxohexanoic acid (4) containing the entire scaffold of temozolomide, a precursor of the DNA-methylating agent clinically approved for the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. For a nitrous amide-based prodrug, we synthesized 2-acetamido-6-(((benzyloxy)carbonyl)(nitroso)amino)-5-oxohexanoic acid (5) containing a N-nitrosocarbamate group, which can be converted to a diazo moiety via a mechanism similar to that of streptozotocin, a clinically approved diazomethane-releasing drug containing an N-nitrosourea group. Preliminary characterization confirmed formation of N-acetyl DON (6), also known as duazomycin A, from compound 4 in a pH-dependent manner while compound 5 did not exhibit sufficient stability to allow further characterization. Taken together, our model studies suggest that further improvements are needed to translate this prodrug approach into glutamine antagonist-based therapy.

Keywords: Prodrug, α-diazoketone, 6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine

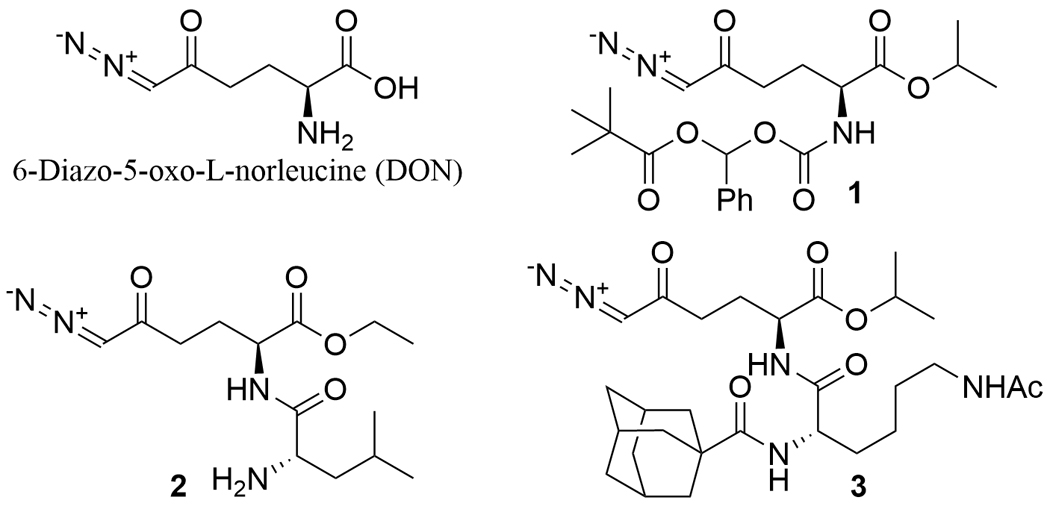

6-Diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine (DON, Fig. 1) is a glutamine analog that acts on a broad range of glutamine-utilizing enzymes by forming a covalent bond with a nucleophilic residue at an active site, resulting in the irreversible inhibition of the enzymes. Given the significance of glutamine metabolism in cancer,1 DON was investigated as a chemotherapeutic agent in a number of clinical studies.2 Its development was, however, hampered by dose-limiting toxicity in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract2 which is enriched with highly glutamine-consuming cells. To this end, various tumor-targeted prodrugs of DON have been explored in an attempt to minimize DON exposure to the GI tract.2 These prodrugs possess promoieties at both the carboxylic acid and α-amino group of DON and no longer have the ability to act on glutamine-utilizing enzymes until being converted back to DON preferentially at the site of action. For instance, prodrugs 13 and 24 showed enhanced brain-plasma ratio for DON with limited GI exposure while prodrug 35 was successfully designed for tumor-targeted delivery (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

6-Diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine (DON) and its representative prodrugs 1-3.

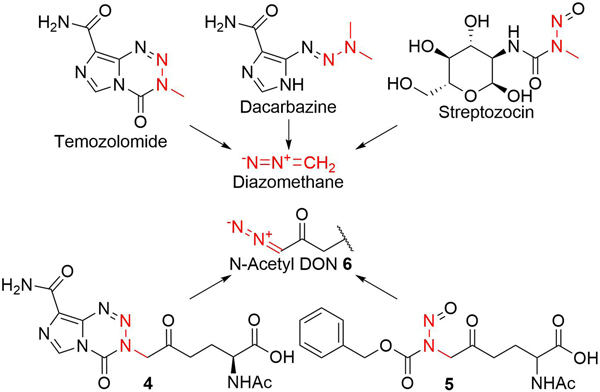

For inhibition of glutamine-utilizing enzymes, the diazo group of DON plays a pivotal role as the warhead by reacting with a catalytic nucleophilic residue of the enzyme. Therefore, another strategy to mask the activity of DON would be to convert the diazo group into an inert diazo precursor. A similar approach has been taken by a number of FDA-approved drugs including temozolomide, dacarbazine, and streptozotocin (Fig. 2), which serve as prodrugs of diazomethane, a DNA-methylating agent. This approach may offer another molecular design strategy for DON prodrugs structurally distinct from those reported to date. Herein we report our efforts toward the synthesis of two DON prodrugs 4 and 5 (Fig. 2) containing a diazo precursor as model compounds to investigate the feasibility to apply this prodrug strategy to DON.

Fig. 2.

FDA-approved prodrugs containing a diazo precursor and DON prodrugs 4 and 5 containing a diazo precursor.

The presence of the ketone group in the vicinity of the α-amino group makes DON prone to intramolecular cyclization, forming a 3,4-dihydro-2H-pyrrole ring.3 Indeed, as exemplified in Figure 1, nearly all DON prodrugs reported to date possess a modified α-amino group to prevent the cyclization. In our prodrug design, we employed N-acetyl DON 6 (also known as duazomycin A) as a parent molecule in order to circumvent the synthetic complexity caused by the undesirable cyclization, aiming to synthesize two DON prodrugs 4 and 5 each possessing a distinct diazo precursor (Fig. 2).

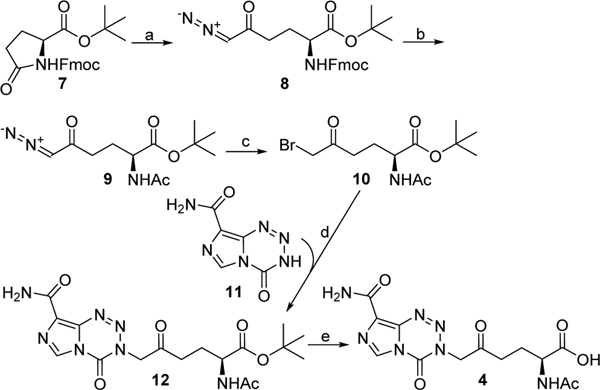

Synthesis of 4 is outlined in Scheme 1. Reaction of Fmoc-protected pyroglutamic acid tert-butyl ester 76 with trimethylsilyldiazomethyllithium afforded compound 8,7 an orthogonally protected derivative of DON. Compound 8 was then converted into the corresponding N-acetyl derivative 9 via removal of Fmoc group by piperidine followed by acetylation. The diazo group of 9 was then replaced by a bromo group by treatment with aqueous HBr to give compound 10. Nucleophilic substitution of the bromide in 10 by the preformed sodium amide of 3,4-dihydro-4-oxoimidazo[5,1-d]-1,2,3,5-tetrazine-8-carboxamide 118 afforded compound 12 in which the entire temozolomide structure is embedded. Subsequent hydrolysis of the tert-butyl ester of 12 with TFA gave the desired product 4.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of compound 4a

aReagents and conditions: (a) (Trimethylsilyl)diazomethane, n-butyl lithium, THF, −95 °C to −78 °C, 67%; (b) (i) piperidine, DMF, rt, (ii) Ac2O, Et3N, CHCl3, 0 °C, 89% for two steps; (c) 48% aq. HBr, Et2O, 20 °C, quant. crude yield; (d) NaH, DMF, −20 °C to 0 °C, 60%; (e) TFA, CH2Cl2, rt, quant. yield.

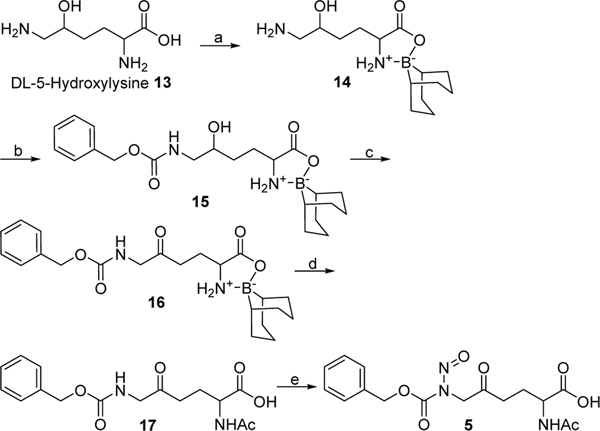

Synthesis of compound 5 is outlined in Scheme 2. DL-5-Hydroxylysine 13 was converted into boroxazolidone derivative 14 by reacting with 9-borabicyclo(3.3.1)nonane (9-BBN). The ω-amino group of 14 was transformed to benzyl carbamate to provide 15, which was subsequently oxidized using Dess-Martin reagent to provide ketone 16. N-Acetyl derivative 17 was obtained by treating 16 with acetic anhydride in a mixture of methanol and chloroform (1:5) to facilitate dissociation of the boroxazolidone complex and simultaneous acetylation of the α-amino group.9 Finally, regioselective N-nitrosation of the carbamate nitrogen of 17 over the α-amino group was achieved by treating with nitrosonium tetrafluoroborate (NOBF4),10 providing the desired product 5. A similar regioselectivity was previously observed in synthesis of N-nitrosochloroethylcarbamate derivative of cephalosporin.11

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of compound 5a

aReagents and conditions: (a) 9-BBN, MeOH, 65 °C; (b) Cbz-Cl, DIEA, THF, 0 °C to rt, 37% from 13; (c) Dess-Martin reagent, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 89%; (d) Ac2O, MeOH-CHCl3 (1:5), rt, 15%; (e) NOBF4, acetonitrile, pyridine, 40 °C to −20 °C, 28%.

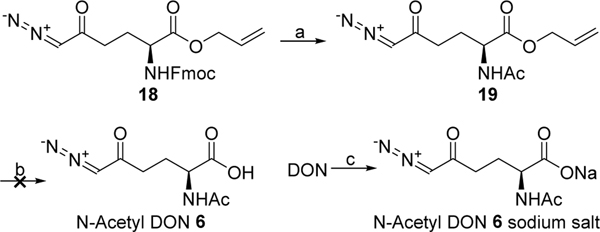

Assuming conversion of their diazo precursor to a diazo group occurs faster than N-deacetylation, both prodrugs 4 and 5 are expected to initially produce N-acetyl DON 6. Although compound 6 was reported as a natural product isolated from Streptomyces ambofaciens nearly 60 years ago,12 its chemical synthesis has not yet been reported in detail. In order to prepare N-acetyl DON 6 as a reference compound, N-Fmoc-DON allyl ester 1813 was converted to N-acetyl DON allyl ester 19 via removal of the Fmoc group followed by N-acetylation with acetic anhydride (Scheme 3). However, our attempt to obtain 6 from 19 by palladium-catalyzed deallylation was unsuccessful. This is presumably due to the poor stability of 6 as a free acid in the absence of the free α-amino group capable of neutralizing the acid in the form of a zwitterion. This prompted us to obtain N-acetyl DON 6 as a sodium salt. Acetylation of DON with acetic anhydride using sodium bicarbonate as a base followed by chromatographic purification without acidic work-up successfully provided N-acetyl DON 6 sodium salt as a stable solid (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of N-acetyl DON 6a

aReagents and conditions: (a) (i) Piperidine, DMF, rt, 48%; (ii) Ac2O, pyridine, DCM, rt, 71%; (b) PhSiH3, Pd(PPh3)4, DCM, 0 °C; (c) Ac2O, NaHCO3, water, rt, 73%.

Given the potentially unstable nature of the diazo precursors introduced to compounds 4 and 5, both compounds were stored at −20 °C as solids and confirmed to be stable at least for a period of 4 months. We noticed, however, that compound 5 degraded within 12 hours as a DMSO solution while conducting NMR measurements at room temperature. The degradation could be triggered by spontaneous formation of a diazo moiety from the N-nitrosocarbamate of 5. The expected degradant, N-acetyl DON 6, however, was not detected suggesting further decomposition as seen during our attempt to obtain 6 as a free acid.

In contrast, compound 4 was found to remain intact in a DMSO solution at least for a period of 24 hours and subsequently evaluated for its stability in pig liver and brain homogenates. These matrices were chosen for initial experiments as we are interested in developing prodrugs preferentially activated in the brain for CNS indications14–16 while minimizing the well-documented GI toxicity of DON.2 As summarized in Table 1, complete loss of the parent compound 4 was observed within 30 min in both matrices, suggesting a rapid formation of a diazo moiety.

Table 1.

Stability of compound 4 in various matrices

| Matrix | % remaining |

|---|---|

| Pig liver homogenates | <5% (at 30 min) |

| Pig brain homogenates | <5% (at 30 min) |

| Potassium phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4) | <5% (at 30 min) |

| Sodium acetate buffer (pH = 4.0) | >95% (at 60 min) |

Subsequent metabolite identification efforts revealed a negligible formation of DON in the pig brain homogenates. The retention time and mass spectrum of the new major peak seen in the brain homogenates (Figure 3B) matched with those of N-acetyl DON 6 (Figure 3A) chemically synthesized as a reference compound. It appears that the 3,4-dihydro-4-oxoimidazo[5,1-d]-1,2,3,5-tetrazine-8-carboxamide moiety of 4 was rapidly converted into a diazo group in the brain homogenates while the N-acetyl group remained intact.

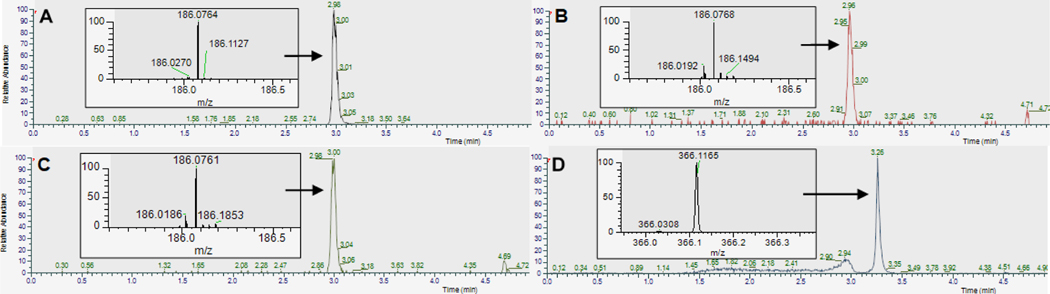

Figure 3.

Extracted ion chromatograms (m/z 186.0752–186.0770 and m/z 366.1138–366.1174) obtained from (A) chemically synthesized N-acetyl DON 6, (B) compound 4 incubated with pig brain homogenate, (C) potassium phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4), and (D) sodium acetate buffer (pH = 4.0). The insets show mass spectra of the indicated peaks. Peaks at 3.0 min in chromatograms A-C represent the metabolite N-acetyl DON 6 detected over an m/z range of 186.0752–186.0770 corresponding to [MH+ - N2] resulting from a loss of a diazo from the parent molecule. A peak at 3.26 min in chromatogram D represents compound 4 detected over an m/z range of 366.1138–366.1174 corresponding to [MH+]. The broad peak seen at 2.7–3.0 min in chromatogram D was confirmed to be unrelated to N-acetyl DON 6.

To determine whether a non-enzymatic process is involved in the disappearance of compound 4, we also investigated the stability of 4 in buffered solutions (Table 1). In a potassium phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4), we again observed the loss of compound 4 and formation of 6 (Figure 3C) similar to what was observed in the pig brain homogenate. In stark contrast, compound 4 was very stable in a sodium acetate buffer (pH = 4.0) over a period of 60 min (Figure 3D). These findings indicate that the urea bond in compound 4 is highly susceptible to a nucleophilic attack of a water molecule at neutral pH. The pH-dependent chemical stability shown by compound 4 is similar to that of temozolomide which was reported to be stable at acidic pH values and labile above pH 7.17 In comparison to compound 4, however, temozolomide displayed greater stability at pH 7.4 with a half-life of 1.83 h. The weaker stability shown by the urea bond of compound 4 can presumably be attributed to its electron-deficient nature caused by the neighboring ketone moiety.

The diazo moiety of DON provides a unique opportunity to design its prodrugs containing a diazo precursor utilized in other clinically available drugs. N-Nitroso-based compound 5 was, however, found to be highly unstable. It is postulated this is initiated by the spontaneous rearrangement to a diazo moiety followed by further degradation. It should be noted that all clinically available N-nitroso-based drugs such as streptozocin contain a nitrosourea scaffold instead of nitrosocarbamate, presumably contributing to their increased stability. Synthetic route depicted in Scheme 2, however, is not suitable for nitrosourea-containing prodrugs due to the difficulty in regioselective nitrosation of a urea moiety. Therefore, an alternative synthetic route needs to be developed to obtain the nitrosourea-based DON prodrugs.

Prodrug 4 was found to undergo pH-dependent conversion to N-acetyl DON. The greater stability of 4 under acidic conditions (pH = 4.5) provides an interesting contrast to DON, which is known to be acid-labile.18 Although one could envision that prodrug 4 could be given orally to prevent acid-mediated degradation in the upper GI, its marked instability at neutral pH will likely pose challenges for further development. The conversion of the 3,4-dihydro-4-oxoimidazo[5,1-d]-1,2,3,5-tetrazine-8-carboxamide moiety to a diazo moiety is triggered by the hydrolysis of the urea bond within the tetrazine ring. Thus, one way to modulate the stability of 4 is to incorporate a substituent to the 6-position, creating a steric hindrance around the urea bond.19 Such modification may lead to acid-resistant prodrugs with acceptable stability at neutral pH that can slowly form a diazo functional group.

In summary, we confirmed that the diazo precursor in compound 4 is transformed into a diazo group, forming N-acetyl DON 6. Since N-acetyl DON 6 is known to be converted into DON by mammalian aminoacylase20 and most likely by other hydrolytic enzymes, compound 4 is expected to eventually produce DON. Our model studies suggest, however, that further improvements are necessary in order to modulate the stability of a diazo precursor for translation of this prodrug approach into practical applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors of this manuscript have been supported by NIH grants P30MH075673 (B.S.S) and R01NS103927 (B.S.S.). The authors are also grateful for the support provided by the Bloomberg-Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy at Johns Hopkins.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.#####.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Li T, Le A. Glutamine Metabolism in Cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1063:13–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemberg KM, Vornov JJ, Rais R, et al. We’re Not “DON” Yet: Optimal Dosing and Prodrug Delivery of 6-Diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine. Mol Cancer Ther. 2018;17:1824–1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rais R, Jancarik A, Tenora L, et al. Discovery of 6-Diazo-5-oxo-l-norleucine (DON) Prodrugs with Enhanced CSF Delivery in Monkeys: A Potential Treatment for Glioblastoma. J Med Chem. 2016;59:8621–8633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nedelcovych MT, Tenora L, Kim BH, et al. N-(Pivaloyloxy)alkoxy-carbonyl Prodrugs of the Glutamine Antagonist 6-Diazo-5-oxo-l-norleucine (DON) as a Potential Treatment for HIV Associated Neurocognitive Disorders. J Med Chem. 2017;60:7186–7198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tenora L, Alt J, Dash RP, et al. Tumor-Targeted Delivery of 6-Diazo-5-oxo-l-norleucine (DON) Using Substituted Acetylated Lysine Prodrugs. J Med Chem. 2019;62:3524–3538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calimsiz S, Lipton MA. Synthesis of N-Fmoc-(2S,3S,4R)-3,4-dimethylglutamine: An application of lanthanide-catalyzed transamidation. J Org Chem. 2005;70:6218–6221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coutts IGC, Saint RE. The reaction of lithium trimethylsilyldiazomethane with pyroglutamates — a facile synthesis of 6-diazo-5-oxo-norleucine and derivatives. Tetrahedron Letters. 1998;39:3243–3246. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moseley CK, Carlin SM, Neelamegam R, et al. An efficient and practical radiosynthesis of [11C]temozolomide. Org Lett. 2012;14:5872–5875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Syed BM, Gustafsson T, Kihlberg J. 9-BBN as a convenient protecting group in functionalisation of hydroxylysine. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:5571–5575. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hendrata S, Bennett F, Huang Y, et al. Syntheses of dipeptides containing (1R,5S)-6,6-dimethyl-3-azabicyclo[3.1.0]hexane-2(S)-carboxylic acid (4), (1R,5S)-spiro[3-azabicyclo[3.1.0]hexane-6,1′-cyclopropane]- 2(S)-carboxylic acid (5) and (1S,5R)-6,6-dimethyl-3-azabicyclo[3.1.0]hexane-2(S)-carboxylic acid (6). Tetrahedron Letters. 2006;47:6469–6472. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander RP, Bates RW, Pratt AJ, et al. A N-nitrosochloroethyl-cephalosporin carbamate prodrug for antibody-directed enzyme prodrug therapy (ADEPT). Tetrahedron. 1996;52:5983–5988. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rao KV, Brooks SC Jr, Kugelman M, et al. Diazomycins A, B, and C, three antitumor substances. I. Isolation and characterization. Antibiot Annu. 1959;7:943–949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wild RC, Estok T. Combination therapy of cancer with a 6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine prodrug and an immune checkpoint inhibitor. 2020. PCT Int. Appl WO2020/150639. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanaford AR, Alt J, Rais R, et al. Orally bioavailable glutamine antagonist prodrug JHU-083 penetrates mouse brain and suppresses the growth of MYC-driven medulloblastoma. Transl Oncol. 2019;12:1314–1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollinger KR, Smith MD, Kirby LA, et al. Glutamine antagonism attenuates physical and cognitive deficits in a model of MS. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2019;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hollinger KR, Zhu X, Khoury ES, et al. Glutamine AntagonistJHU-083 Normalizes Aberrant Hippocampal Glutaminase Activity and Improves Cognition in APOE4 Mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;77:437–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Denny BJ, Wheelhouse RT, Stevens MF, et al. NMR and molecular modeling investigation of the mechanism of activation of the antitumor drug temozolomide and its interaction with DNA. Biochemistry. 1994;33:9045–9051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan MP, Nelson JA, Feldman S, et al. Pharmacokinetic andphase I study of intravenous DON (6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine) in children. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1988;21:78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lunt E, Newton CG, Smith C, et al. Antitumor imidazotetrazines. 14. Synthesis and antitumor activity of 6- and 8-substituted imidazo[5,1-d]-1,2,3,5-tetrazinones and 8-substituted pyrazolo[5,1-d]-1,2,3,5-tetrazinones. J Med Chem. 1987;30:357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson EP, Brockman RW. Biochemical Effects of Duazomycin a in the Mouse Plasma Cell Neoplasm 70429. Biochem Pharmacol. 1963;12:1335–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.