Abstract

Ru(II) complex photocages are used in a variety of biological applications, but the thermal stability, photosubstitution quantum yield, and biological compatibility of the most commonly used Ru(II) systems remain unoptimized. Here, multiple compounds used in photocaging applications were analyzed, and found to have several unsatisfactory characteristics. To address these deficiencies, three new scaffolds were designed to improve key properties through modulation of a combination of electronic, steric, and physiochemical features. One of these new systems, containing the 2,2′-biquinoline-4,4′-dicarboxylic acid (2,2’-bicinchoninic acid) ligand, fulfills several of the requirements for an optimal photocage. Another complex, containing the 2-benzothiazol-2-yl-quinoline ligand, provides a scaffold for the creation of “dual action” agents.

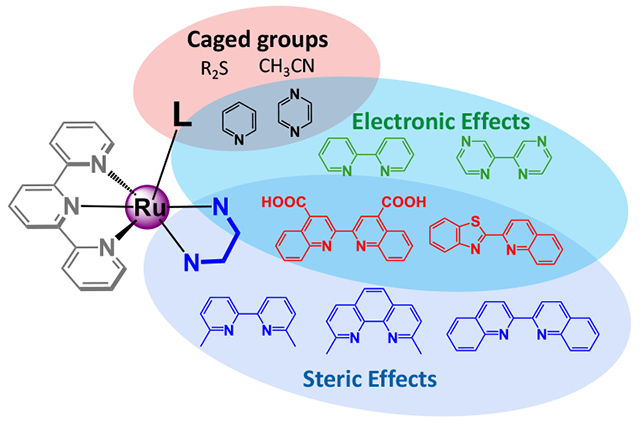

Graphical Abstract

A comparison of commonly used Ru(II) photocages demonstrated that they suffer from multiple drawbacks which limit their utility in biological applications. Synthetic modulation of the metal scaffold allowed for the development of improved systems for either photocaging or dual action applications through careful regulation of both steric and electronic properties.

INTRODUCTION

Photo-labile systems are used in a variety of applications, ranging from materials to biomedical research.1, 2 Photons, coupled with compounds that can undergo photochemical transformation, provide the ability to control the location and timing for a physical effect through bond breakage or formation. Such systems are often termed “photocages”. Photocages are distinct from “photoswitches”3 as the photochemical transformation is irreversible in a photocage. However, just like a photoswitch in the “off” position, it is essential that a photocage is biologically inert when intact. There must also be no activity from the empty “cage” to prevent interference with the biological effects from the released moiety (the caged ligand) under study.

While organic photocages have broad utility, metal centers were introduced as quasi-orthogonal protecting groups that could both expand the repertoire of the types of functional groups that can be “caged”, and also shift absorption profiles into the visible and near-IR region. This allows for improved medical utility due to deeper penetration of photons, and decreases the potential for adverse effects on cell health that is commonly induced by UV irradiation. Ru(II) complexes have been particularly effective for photocaging applications, and multiple groups have explored their use for photo-delivery of drugs4–9 and signaling molecules.10–19

In contrast to a standard photocage, metal-based systems can provide additional functions if the released metal is active itself. This results in “dual action” agents, where both the released ligand and the metal center each provide unique, preferably complementary biological effects.20, 21 While many of the desired features for optimal photocages and “dual action” agents are shared, the most important distinction is the biological activity (or lack thereof) of the caging group following light irradiation. The released inorganic caging group is what we term the “scaffold”; it also serves as the synthetic building block for creating the photocaged complex when coordinated to biologically active ligands. The photochemistry and biological activity of the photocaged complex, and thus its utility, depends upon each of the associated spectator ligands, the three-dimensional structure of the complex, and the nature of the metal itself. We hypothesized that rationally varying the ligand components and structures of the metal complex could result in scaffolds with superior properties for photocaging applications. Alternatively, other scaffolds would function better as “dual action” agents.

In addition to the properties of the metal complex and associated ligands, the “caged” organic group plays an essential role. Different “caged” groups have been used by a variety of researchers, including imidazole, pyridine, diazines, amines, nitriles, and thioethers. Each of these functionalities can be incorporated in more sophisticated organic molecules for light-triggered release. For example, the seminal work in this area was performed by Etchenique, who developed phototriggered Ru(II) complexes that released nitrogen-containing neurotransmitters.10–16 The Bonnet group demonstrated that thioethers such as N-acetylmethionine can be caged and released,22 and Kodanko and Turro have shown a variety of nitriles can be similarly caged, such as peptide-based protease inhibitors.17, 23 Vasquez developed a Ru-coordinated histidine building block for Fmoc/tBu solid-phase peptide synthesis, allowing for the development of caged peptides,24 and Renfrew has used imidazole-containing drugs for photodelivery.4–6 Each of these and many other studies demonstrated different utilities of the basic system, but, to the best of our knowledge, there has not been a direct comparison of the most effective “caging” scaffolds or “caged” functional groups.

In previous work, we established that steric effects could be used to increase the quantum yields for photosubstitution (ΦPS) of Ru(II) complexes used in biological applications.25–28 Steric clash between the coordinated ligands results in elongation and/or distortion of metal-ligand bonds, and distortions within the ligand structure. These structural perturbations lower the energy of a dissociative 3MC (metal centred) state, and allows for thermal population following photoexcitation to the 3MLCT (metal to ligand charge transfer) state. Population of the 3MC causes the ejection of a ligand.29–31 This principle has been applied extensively to inorganic photocages by incorporating spectator ligands that induce steric clash.

Recently, we showed that electronic effects of the “caged” group could also be employed to regulate ΦPS in Ru(II) complexes,32 providing an alternative strategy for fine tuning of photochemistry. This project led us to investigate the interplay of steric and electronic features that impact the photochemistry of Ru(II) complexes. However, each structural modification impacted more than the single desired property, and thus altered the utility of a system for use as either a photocage or a “dual action” agent. A more systematic investigation was needed.

In this study we have focused on the impact of modulating steric and electronic features on five key properties: 1) the peak of the lowest energy absorption (λmax); 2) the photosubstitution quantum yield (ΦPS); 3) stability under biological conditions (defined as % of intact compound remaining at a specific time point); 4) cytotoxicity in the dark; 5) cytotoxicity in the light. Cytotoxicity is normally quantified using EC50 or IC50 values, i.e., the effective or inhibitory concentration for 50% of the toxic effect. High values for items 1–4 are generally desirable for both a photocage and a “dual action” agent. In contrast, light-induced cytotoxicity (associated with a low IC50 value) is desired only in the case of a “dual action” agent; it would be detrimental in the case of a photocage.

The majority of published Ru(II) compounds for photocaging applications possess considerable cytotoxicity of the intact form before irradiation, which limits the utility of these agents. Also, while there have been notable improvements of photophysical and photochemical features, reports of the thermal stability are inconsistent or have not been systematic; however, poor stability is a common problem for Ru(II) cages. In this work we report our advances towards optimal Ru(II) photocages and “dual action” agents through the creation of new Ru(II) scaffolds. In pursuit of this goal we also aimed to address the following key questions: 1) What is the impact of the most common “caged” organic functional groups on ΦPS and thermal stability? 2) What is the effect of bidentate spectator ligands that contribute steric bulk on key properties? 3) What features (electronic, steric or both) would allow for the optimization of photocages or “dual action” agents? And finally, 4) How can biocompatibility be achieved?

RESULTS

Design and Synthesis.

Ru(II) complexes can potentially release multiple ligands, but for this study we focused on a simple system that can only release one ligand. The complexes were designed as [Ru(tpy)(NN)L], where tpy = 2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine, NN is a variety of bidentate ligands, and L is the “caged” monodentate ligand that can be released upon irradiation (Chart 1, top). The two chelating ligands were used as they are expected to remain bound to the metal. This ensures only a single photochemical product resulting from the loss of the monodentate ligand.

Chart 1.

Ru(II) complexes investigated in this study. The scheme at the top depicts the photochemical or thermal ligand exchange of the monodentate ligand. The bidentate and monodentate ligands are varied in the complexes as shown. Ligand structures depicted in green reflect alterations in electronic properties, structures in blue reflect changes in the steric properties, and ligands shown in red exhibit a mixture of steric and electronic effects.

The tridentate tpy ligand was included in all complexes, and both the bidentate and monodentate ligands were then varied to investigate the effects of ligands that contributed steric bulk, electronic effects, or both. The monodentate ligands used were acetonitrile, N-acetylmethionine, pyridine, and pyrazine.33 The bidentate systems studied were 2,2’-bipyridine (bpy), 2,2’-bipyrazine (bpz), 6,6’-dimethyl-2,2’-bipyridine (dmbpy), 2,9-dimethyl-1,10-phenanthroline (dmphen), 2,2’-biquinoline (biq), 2,2′-biquinoline-4,4′-dicarboxylic acid (2,2’-bicinchoninic acid, bca), and 2-benzothiazol-2-yl-quinoline (btz-qui). In total, 12 compounds were synthesized based on seven scaffolds to perform a detailed structure-property analysis.

First, we synthesized the most commonly used Ru(II) photocages according to published procedures (compounds 1,34 2,32 3,35 4,22 6,34 and 934), and evaluated their performance. The systems were then redesigned to improve key properties. Compounds 5, 7, 8, and 10–12 are novel compounds and were synthesized for the first time. The complexes were purified to ensure no contamination of either free ligands or coordinatively unsaturated Ru(II) centers. All the complexes are +2 charged except for complex 11, which is neutral, as the bca ligand contains two carboxylic acids that were deprotonated under the experimental conditions. The complexes were characterized by 1H NMR spectroscopy, ESI-MS, X-ray, and UV/Vis spectroscopy (see Figures S8–18, S23–35 in the Supporting Information).

Structure-property analysis of photocaged systems.

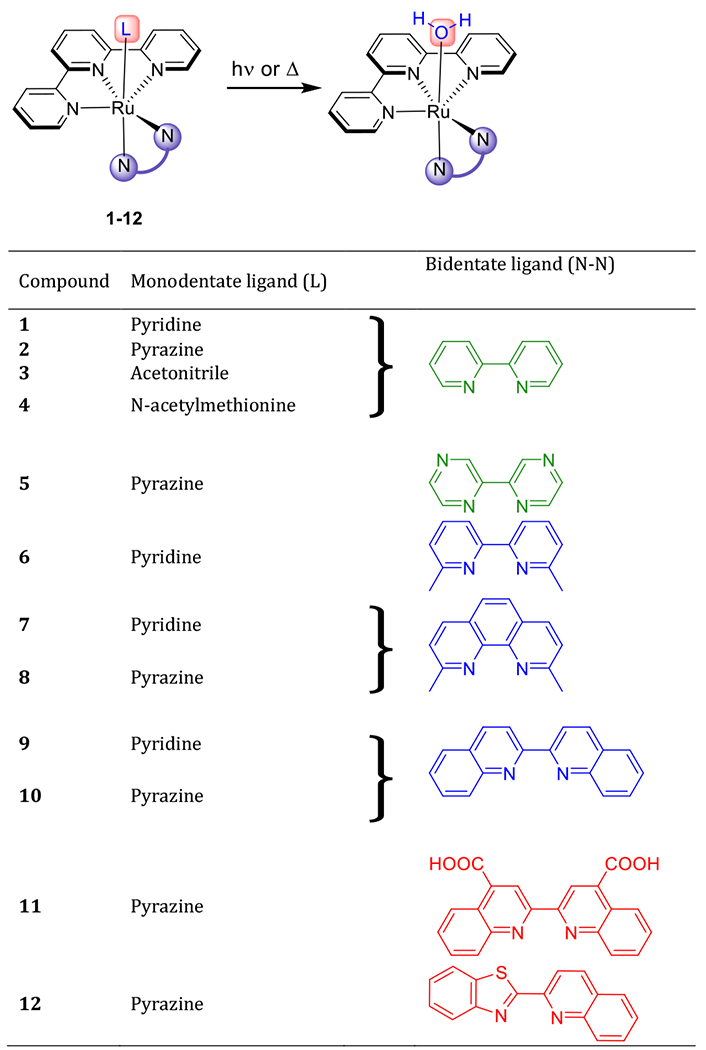

As shown in Figure 1, the absorption profiles of the different photocages varied slightly as a function of the monodentate “caged” ligand (Figure 1A) and more significantly with different bidentate ligands (Figure 1B). Both mono- and bidentate ligands had an impact on the λmax and extinction coefficient (ε) values, with extended conjugation of the bidentate ligands inducing bathochromic shifts, as anticipated. In order to standardize photochemical evaluation, the ΦPS for all systems was determined using 470 nm light in H2O. Large variations were observed, with ΦPS ranging from <0.0001 to 0.141. The photophysical and photochemical characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Comparison of normalized UV/Vis profiles of Ru(II) complexes in H2O as a function of variation of the monodentate ligand (A) and bidentate ligand (B). Concentrations of ~10μM were used in the measurements.

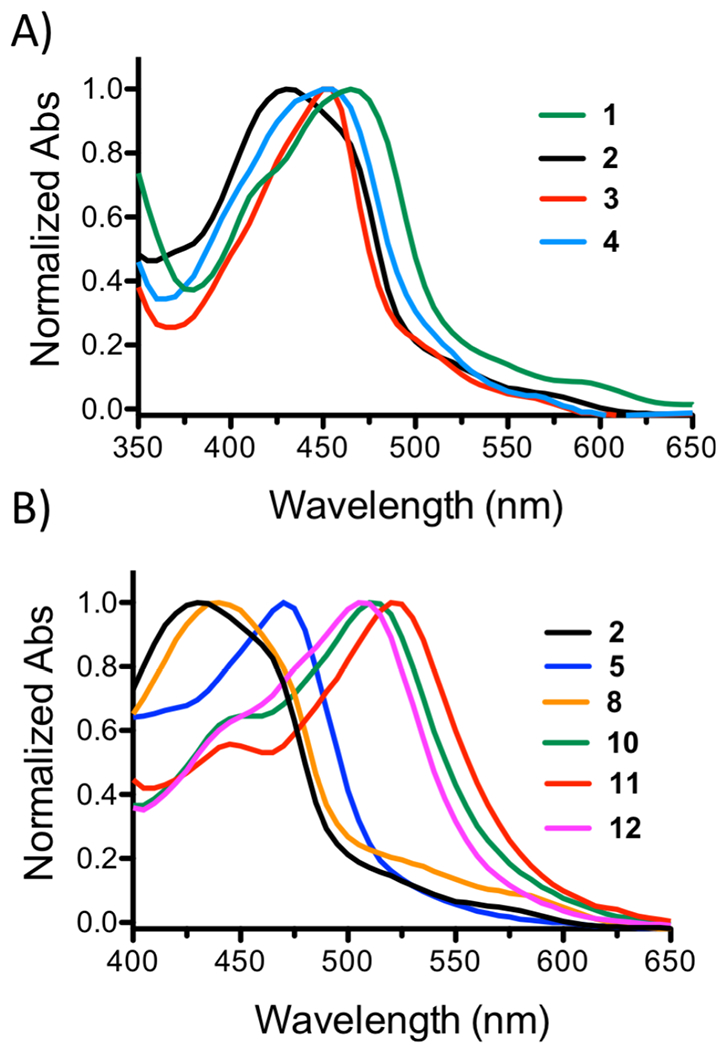

Table 1.

Photophysical and Biological Properties.

| Compound | λabs MLCT (nm) (ε (M−1cm−1)) a |

ΦPS (H2O) | Stabilityb | IC50, μMc |

PId | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dark | Light | |||||

|

| ||||||

| 1 | 468 (8,100)34 | n.d. | 100 | >100 | >100 | - |

| 2 | 430 (10,000)32 | 0.0013(2) | 100 | >100 | >100 | - |

| 3 | 454 (10,900)35 | 0.0125(3) | 84 | >100 | >100 | - |

| 4 | 452 (5,400)22 | 0.0027(2) | 100 | >100 | >100 | - |

| 5 | 465 (6100) | 0.0007(2) | 100 | 30±2.8 | 24.2±2.1 | >1.2 |

| 6 | 471 (8,000)34 | 0.104(1) | 34 | >100 | 42.6±2.5 | >2.3 |

| 7 | 470 (12,000) | 0.058(2) | 48 | >100 | 66±9.6 | >1.5 |

| 8 | 440 (10,000) | 0.132(1) | 8 | >100 | 58.9±6.3 | >1.7 |

| 9 | 530 (9,000)34 | 0.014(2) | 82 | 30.8±1.9 | 11±0.2 | 2.8 |

| 10 | 510 (9,900) | 0.141(2) | 63 | 34.6±0.3 | 17.7±0.1 | 1.9 |

| 11 | 520 (6,600) | 0.121(2) | 69 | >100 | >100 | - |

| 12 | 505 (8,300) | 0.0368(4) | 84 | ~100 | 27.6±3.4 | >3.6 |

Indicates previously reported values.

Determined as % remaining at 24 h (37 °C) in H2O, calculated by optical and HPLC approaches.

Cytotoxicity of compounds evaluated in the HL-60 cell line (averages of three measurements). This cell line was chosen as it is sensitive to a variety of toxic agents, allowing for detection of biological effects that might not be observed in a more resistant cell line. The IC50 value of cisplatin is 3.1 ± 0.3 μM in this cell line.

The phototoxicity index (PI) is the ratio of the dark and light IC50 values.

A high thermal stability is needed for compounds to serve as useful photocages for most biological or materials applications. The stability of each complex was assessed over 24 and 72 hours under aqueous conditions at 37 °C. First, the different photocaging functional groups, nitrile, thioether, pyridine, and pyrazine, were compared in complexes 1–4. Notably, the nitrile was the only monodentate ligand that created a thermally unstable complex (compound 3); compounds 1, 2, and 4 exhibited no degradation over 24 hr. However, they also exhibited 10-fold lower ΦPS than compound 3.

Next, the effect of strain-inducing spectator ligands on thermal stability was studied in complexes 6–10, and compared with ΦPS. Inclusion of dmbpy (6), dmphen (7) and biq (9) into [Ru(tpy)(NN)(py)] systems resulted in an inverse relationship between ΦPS and stability (Fig. 3A). The compounds with the higher quantum yields (6 and 7, >0.05) degraded by 52–76% over 24 hr (Table 1, Fig. 2A). In contrast, there was a better retention of stability with an increase in ΦPS when electronic features were altered by changing the monodentate ligand from pyridine to pyrazine. However, the extent of this effect was found to be dependent on the identity of the strain-inducing ligand. For example, systems 7 vs. 8 that contain the dmphen ligand exhibited a 7% increase in quantum yield upon substituting pyrazine for pyridine, but this was associated with a 40% reduction in the stability of the complex. The biq co-ligand was superior, as a 13% increase in quantum yield was associated with only a 20% reduction in stability with replacement of pyridine with pyrazine (complex 9, 10). However, none of the strain-inducing ligands produced thermally stable complexes on a 72 hr time scale (Figure S22). This raised an obvious challenge: how to create a photocage with a sufficient ΦPS for utility without a concomitant loss in thermal stability.

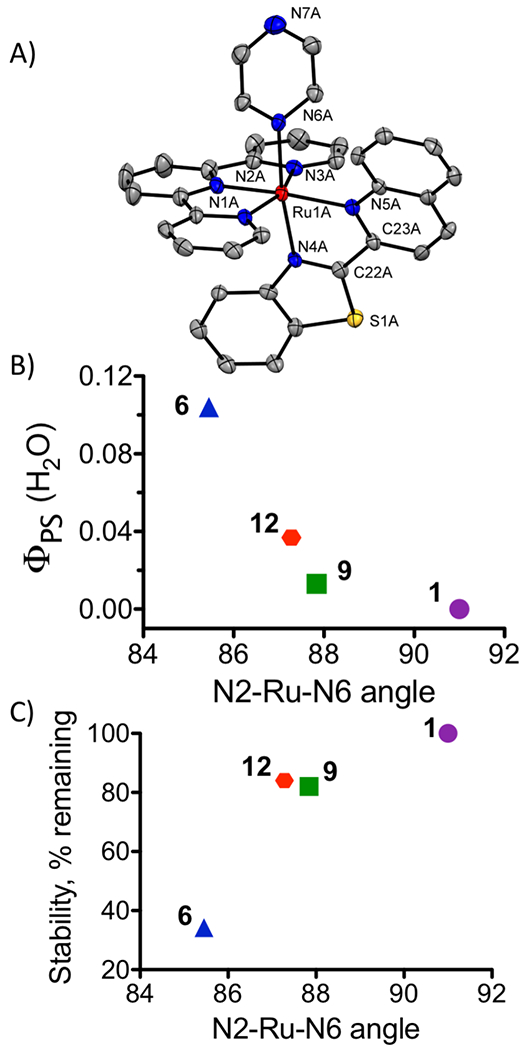

Figure 3.

Effect of structure on ΦPS and stability. (A) Elipsoid map of 12 with hydrogens omitted for clarity. (B) Correlation of ΦPS with selected bond angle demonstrates that there is an inverse relationship as the bond angle approaches 90°. (C) Stability increases as the selected bond angle approaches 90°.

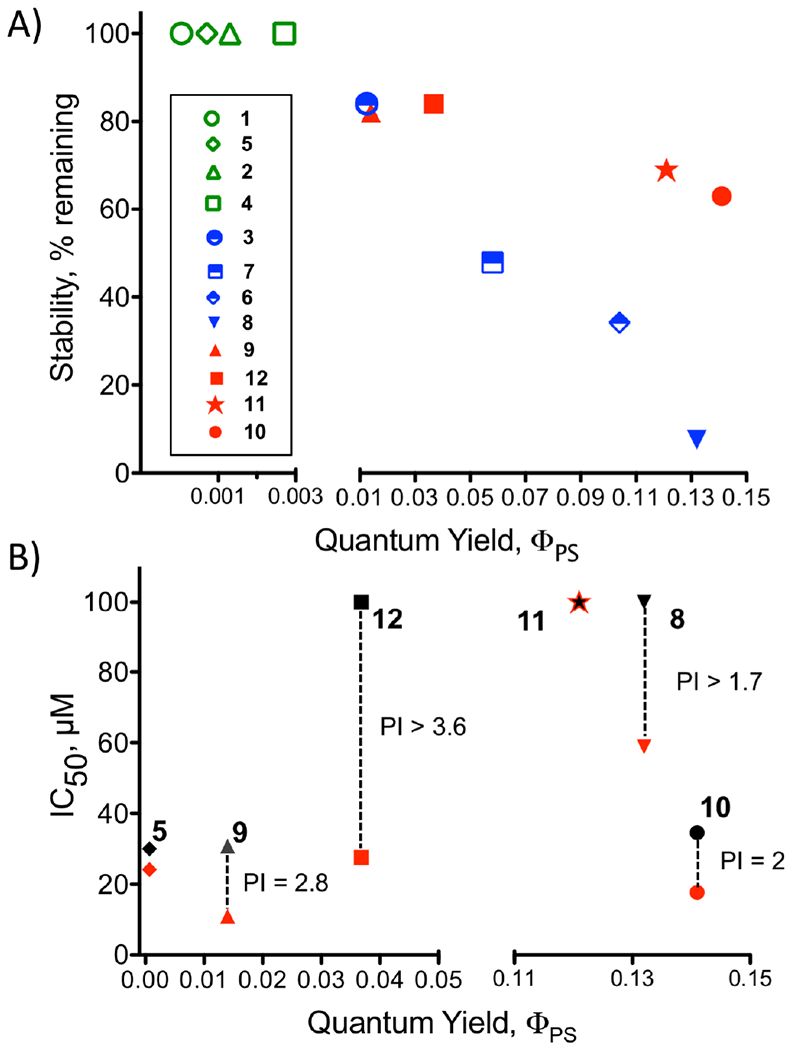

Figure 2.

Key properties for photocages. (A) Correlation between ΦPS and stability (at 24 hr). Green labels indicate compounds with high stability but low ΦPS; red labels indicate compounds with λabs > 500 nm; blue labels are used for compounds with strain inducing ligands or a labile nitrile. (B) Correlation between ΦPS and cytotoxicity IC50 (dark, black; light, red; the PI is shown for emphasis).

Strategies to optimize the photocaging scaffold.

The suboptimal qualities of the commonly used cages motivated the investigation of alternative approaches to change the Ru(II) scaffold in order to increase ΦPS while maintaining stability. It is known that tris homoleptic Ru(II) complexes that contain the bipyrazine ligand are photolabile;36, 37 this is in contrast to the bipyridine ligand, which generally produces photostable complexes. Accordingly, the bipyrazine ligand was incorporated into a scaffold to form complex 5. Due to the mer arrangement of the tpy ligand, one of the bipyrazine rings is trans to the leaving ligand, so it was anticipated that the more electron deficient heterocycle would exert an effect through a shared orbital. However, while the switch from bpy to bpz resulted in a complex that was thermally stable, there was a loss in photochemical reactivity (ΦPS = 0.0007 vs. 0.0013 for the analogous complex 2 with bpy). This demonstrated that electronic modulations that work for the monodentate ligand32, 38 do not translate in this case for the bidentate ligand. Thus, the focus shifted to ligands that induce moderate steric clash compared to dmbpy and dmphen.

Following our demonstration of the use of 2,2’-biquinoline to make Ru(II) complexes that can be activated with red and near-IR light for biological applications,25 this ligand has been successfully applied in the creation of several photocages.4, 5, 34, 39–45 However, complexes containing the biq ligand have notably higher cytotoxicity than complexes with bpy or phen ligands. This limits the utility of biq-containing systems as photocages in live cells. With the aim of reducing toxic effects while preserving the photoreactivity and low energy absorption, two strategies were investigated: adding negatively charged groups to biq to modulate physiochemical properties, and altering the core ligand structure.

To test the first approach, the 2,2′-biquinoline-4,4′-dicarboxylic acid (bca) ligand was incorporated, which resulted in the neutral Ru(II) complex 11. It was anticipated that the carboxylates would alter interactions with biomolecules responsible for the cytotoxicity in the absence of irradiation. In a second approach, the ligand structure of biq was modified by replacement of one of the coordinating ring systems. This bidentate ligand, 2-benzothiazol-2-yl-quinoline (btz-qui), was used in complex 12. Complex 11 exhibited a slight increase in thermal stability (69 vs. 63%) and a slight decrease in ΦPS compared to complex 10 (0.121 vs. 0.141; Table 1). Complex 12 exhibited greater stability (84% remaining at 24 hr) but a 3-fold lower ΦPS than the corresponding biq complex 10.

Effect of structure on ΦPS and stability.

The structure of complex 12 was determined by X-ray crystallography in order to rationalize the modifications in stability and ΦPS. As expected, the inclusion of the btz-qui ligand in complex 12 resulted in a distorted octahedral geometry. In contrast to Ru(II) complexes containing the analogous asymmetric pyridine-benzazole ligand,46 where the two rings of the bidentate ligand are essentially co-planar, the benzothiazole-quinoline system of 12 exhibits a bowed shape (Fig. 3A, S1). In addition, the btz-qui ligand is tilted from the N4-Ru-N5 plane, with a N5-Ru-N4-C22 torsion angle of 17.91° and a N4-Ru-N5-C23 torsion angle of 18.35° (Fig. S1; selected bond lengths and angles are listed in Table S2). As the bridging carbons are below the plane of the coordinating nitrogen, this results in slightly misdirected metal-ligand bonds.47

The Ru–N bond distances involving the tpy ligands are essentially unaltered with the btz-qui ligand in comparison to the biq ligand. However, the asymmetric btz-qui ligand resulted in a larger disparity of Ru–N4 and Ru–N5 bond distances (2.075 and 2.134 Å) compared to the corresponding complex 9 containing the symmetric biq coligand (Table S2, 2.101 and 2.115 Å).34 The benzothiazole ring of the btz-qui ligand is coordinated trans to the labile pyrazine, and the Ru-N6 bond distance for the monodentate pyrazine ligand is also slightly shorter than distances to the pyridine in 1, 6, and 9 (from 0.012–0.026 Å). However, no correlation was observed between the bond length and ΦPS or stability of the complexes.

The bond angles between pyrazine ligand and tpy (N2-Ru-N6, 87.28°) or quinoline (N5-Ru-N6, 97.48°) are nonequivalent, indicating that pyrazine is significantly tilted toward the tpy ligand. Although the N2-Ru-N5 bond angles for the trans ligands are essentially identical in 9 and 12 (175.61° and 175.24°, respectively), the adjacent N5-Ru-N6 bond angle for 12 exhibits a larger distortion from the ideal 90° (at 97.5°). Importantly, the tilts of the monodentate ligands toward the N2 atom of the tpy ligand were found to correlate with both the stability of complexes and ΦPS in water for 1, 6, 9, and 12, as shown in Fig. 3B and C. This tilt results in a misdirected metal-ligand bond, which affects partitioning into the dissociative 3MC (metal-centered state). Thus, the angle of the bond between the ligand and metal center appears more important than the bond lengths for photochemical and thermal features.

Cytotoxicity analysis.

A structure-activity analysis assessing cytotoxicity was performed aiming to identify the scaffolds with suitable biocompatibility. Cell death was determined after 72 hr incubation with the complexes in the dark, or following a 1 hr incubation and subsequent light exposure (22 J/cm2) before the 72 hr incubation. Notably, in the dark, all photocages containing bpy, dmbpy, and dmphen ligands (1–4, 6–8) were not cytotoxic at concentrations up to 100 μM. Surprisingly, the inclusion of the 2,2’-bipyrazine ligand resulted an IC50 value of ca. 30 μM for 5. Complexes 9 and 10, which contain biq ligands, also were relatively toxic, and exhibited IC50 values of ca. 30 μM. Thus, it was concluded that photocages containing biq and bpz ligands should be avoided due to their intrinsic cytotoxicity. Gratifyingly, complexes 11 and 12, with the btz-qui and bca ligands, exhibited IC50 values of 100 μM or higher in the dark.

Exposure to light increased the cytotoxicity of several complexes. To determine if toxicity was due to singlet oxygen (1O2) production, Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green, a fluorescent reporter, was used to determine the ability of the compounds 3–5 and 9–12 to create this toxic species. Tris-(bipyridine)ruthenium(II) ([Ru(bpy)3]2+) was used as a positive control, with a quantum yield for 1O2 production (Δo) of 0.22. In contrast to [Ru(bpy)3]2+, none of the compounds exhibited 1O2 production (Fig. S7). An alternative explanation would be that the released ligands are toxic. There has been some controversy over tris-bidentate complexes that eject strained, bidentate ligands, where it is questioned if the ligand-deficient metal or the liberated ligand is the cytotoxic species.48–50 However, the complexes that were most effective for cell killing ejected the monodentate pyridine and pyrazine, both of which are inactive51 This supports the interpretation that the specific structure of the ligand-deficient Ru(II) complex is the component responsible for the observed activity, and facilitates the construction of “dual action” agents.

In contrast to photocages, low IC50 values would be desired for scaffolds used to create dual action agents. While complex 9 was the most potent (IC50 = 11 μM), this complex has a small phototoxicity index (PI, Table 1, Fig. 3B) due to the cytotoxicity of the complex in the dark. Complex 10 suffers from the same issue, but has a 10-fold higher ΦPS than 9. While the IC50 for complex 12 is more modest (27.6 μM), the lower toxicity in the dark (56% viable cells at 72 h post addition of 100 μM 12) makes this the most promising scaffold. However, the specific mechanism by which the compound exerts a toxic effect remains to be established. Depending on the biological target of this complex, there may be the potential for synergy with a carefully chosen organic ligand.

DISCUSSION

Ru(II) complexes have been used extensively for photocaging approaches. This includes applications in biology, as addressed in this report, but also in materials, for example for development of molecular machines,52 surface modification,53 or regulation of hydrogel properties.54 However, to our knowledge there has not been a comparison of the properties of the most commonly used Ru(II) photocaging scaffolds or photo-releasable functional groups. As a result, scientists are utilizing systems that may not be optimal for the chosen application. Moreover, there are significant limitations to some of the most commonly applied Ru(II) photocage scaffolds. The most prominent drawbacks are lack of thermal stability and significant cytotoxicity.

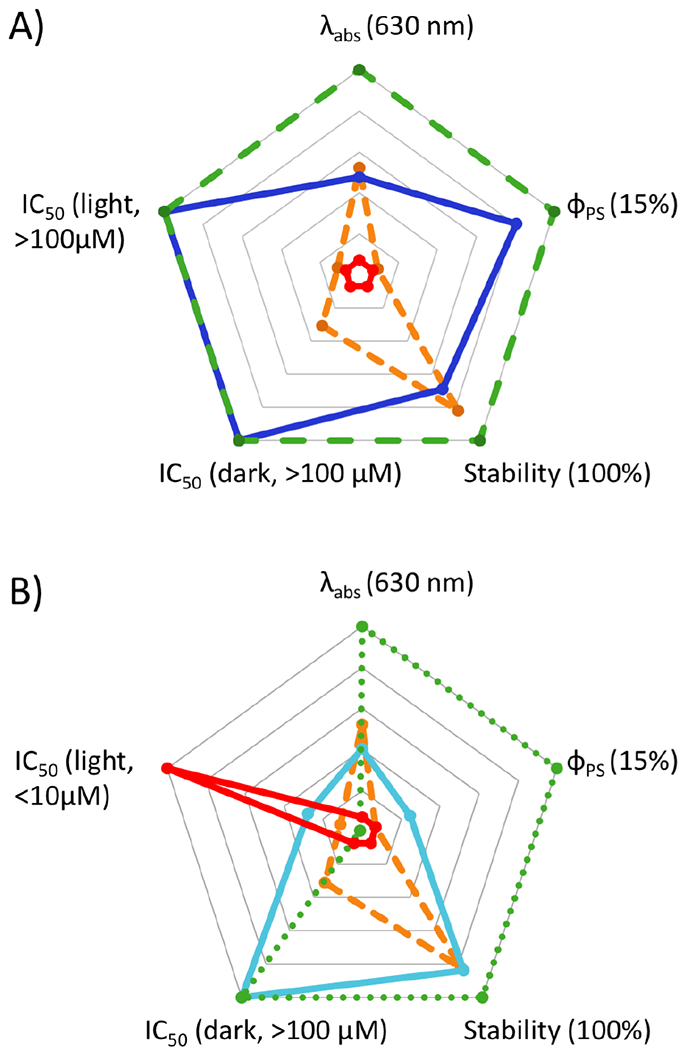

Here, we considered five key properties: 1) absorption λmax; 2) ΦPS; 3) stability under biological conditions; 4) cytotoxicity in the dark; and 5) cytotoxicity in the light. These parameters are depicted in the radar charts shown in Fig. 4. In our view, an optimal “pure photocage” would exhibit long wavelength absorption, moderate ΦPS (to provide for facile activation by light but still allow for handling under experimental conditions), high thermal stability, and low cytotoxicity both before and after light activation. In contrast, an ideal “dual action” agent would have the same features, except for the fact that the scaffold would be cytotoxic following activation with light. It is the balance of these five features, rather than any one feature, that defines a good photocage or dual action scaffold.

Figure 4.

Radar charts for comparison of the key features for photocages (A) and dual action agents (B). A) The “ideal pure photocage” (dashed green) compared with a hypothetical negative control (solid red), compound 9 (dashed orange), and 11 (solid blue). The axes scale from center to perimeter as follows: Absorbance, 420–630 nm; ΦPS, 0–15 %; stability (%) and IC50 for cytotoxicity (μM), 0–100. The desired parameters for an “ideal pure photocage” are indicated in parentheses. B) The “ideal dual action agent” (dotted green) compared with the hypothetical negative control (solid red), compound 9 (dashed orange), and 12 (solid aqua). Note: the axes scales and desired parameters are the same as for A) except for the IC50 (light), which scales from 1–100 μM from the center to perimeter. For a dual action agent, a low value is preferred.

Accordingly, the impact of both the photocaged functional group and the bidentate spectator ligand on each of these properties was assessed. The caged functional group was found to have a minor impact on λmax (Fig. 1A), but caused significant variation in ΦPS and stability (Fig. 2A). Unfortunately, while nitriles have the higher ΦPS, this comes at the cost of some stability (16% degraded over 24 h). Either pyrazine or thioether functional groups were found to be preferable when thermal stability is an important feature, as these functional groups exhibited 100% stability over the same time period. Notably, none of the photocaged groups caused cytotoxicity in the dark or in the light. As the identity of the photocaging functional group (nitrile, thioether, pyridine, or pyrazine) can be changed if this is not essential for the activity of the liberated ligand, this information allows for the rational choice of the metal-binding component for improved photocages.

The bidentate ligand had a larger impact on λmax; shifts of up to 100 nm were achieved by changing the chelating ligand (Fig. 1B). There was also a 200-fold range in values for ΦPS, but enhanced photolability was associated with decreased thermal stability. The effect was structure dependent; notably poor thermal stabilities were found with complexes containing the dmbpy and dmphen ligands compared to biq or bca complexes with comparable ΦPS values (compounds 7, 8, 10, and 11; Fig. 2A). Photocages containing biq, bca, and btz-qui ligands all exhibited longer wavelength λmax values, and good ΦPS. The thermal stabilities were in the range of 63–84% at 24 hrs, making them potentially useful for shorter biological experiments. However, these findings demonstrate that complexes containing the biq ligand should be avoided in many experiments due to their intrinsic cytotoxicity, which does not require light activation. In contrast, compounds 7 and 8 exhibited low dark toxicities, but given their poor stability, these do not appear to be highly biocompatible scaffolds.

The redesign of the Ru(II) scaffold by incorporating carboxylic acids or changing one half of the biq ligand resulted in complexes 11 and 12. Both complexes exhibited low toxicity in the dark. In contrast to commonly used Ru(II) photocages, it appears that the scaffolds including the bca and btz-qui ligands are more biocompatible, and thus, suitable for photobiological applications. Of course, the effect of each complex is anticipated to depend on several variables, including the specific cell line used, the compound exposure time, light dose, and time period of the experiments.55 However, these results suggest that inclusion of negatively charged groups or other ligand modifications can be used to abrogate the cytotoxicity of Ru(II) complexes. This will be addressed in another report.

Notably, in complexes containing bidentate ligands other than bpy, photoejection was associated with an increase in cytotoxicity. However, PI values were generally modest. Of all the scaffolds that were non-toxic in the dark, the [Ru(tpy)(btz-qui)] scaffold in 12 provided the most significant increase in cytotoxicity (Fig. 2B). These results encourage the use of this system in the development of “dual action” agents.

In contrast, the [Ru(tpy)(bca)] scaffold in 11 is preferred for pure photocaging applications. This system is nontoxic both in the dark and following activation by light. This lack of toxicity is desirable in cases where the activity of the liberated ligand is the focus, and effects of other active species in the biological environment will only confuse the results. Moreover, the complex has a high ΦPS in water, and sufficient stability to allow for experiments that require hours of exposure time. We propose that the use of this scaffold will improve the performance of Ru(II) based photocages.

CONCLUSION

This work demonstrates the steric, electronic, and physiochemical features that can be used to tune photochemistry of Ru(II) complexes. While the results are most directly relevant for work that utilizes these coordination complexes for biological applications, the findings are also applicable for any systems that rely on Ru(II) photochemical transformations. Scientists can use the data described here to choose the optimal scaffold for their specific application needs based on the various characteristics of λmax, ΦPS, stability, and biological compatibility both before and after light-mediated release of coordinated ligands.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We gratefully acknowledge the National Institutes of Health (Grant GM107586) for the support of this research. Crystallographic work was made possible by the National Science Foundation (NSF) MRI program, grants CHE-0319176 and CHE-1625732.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

General information on synthetic methods, characterization, photochemical and photobiological analysis, and additional figures.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- (1).Ankenbruck N; Courtney T; Naro Y; Deiters A Optochemical Control of Biological Processes in Cells and Animals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2018, 57 (11), 2768–2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Russew MM; Hecht S Photoswitches: from Molecules to Materials. Adv. Mater 2010, 22 (31), 3348–3360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Velema WA; Szymanski W; Feringa BL Photopharmacology: Beyond Proof of Principle. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136 (6), 2178–2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Wei J; Renfrew AK Photolabile Ruthenium Complexes to Cage and Release a Highly Cytotoxic Anticancer Agent. J. Inorg. Biochem 2018, 179, 146–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Chan H; Ghrayche JB; Wei J; Renfrew AK Photolabile Ruthenium(II)-Purine Complexes: Phototoxicity, DNA Binding, and Light-Triggered Drug Release. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2017, 2017 (12), 1679–1686. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Karaoun N; Renfrew AK A Luminescent Ruthenium(II) Complex for Light-Triggered Drug Release and Live Cell Imaging. Chem. Commun 2015, 51 (74), 14038–14041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Smith NA; Zhang P; Greenough SE; Horbury MD; Clarkson GJ; McFeely D; Habtemariam A; Salassa L; Stavros VG; Dowson CG; Sadler PJ Combatting AMR: Photoactivatable Ruthenium(II)-isoniazid Complex Exhibits Rapid Selective Antimycobacterial Activity. Chem. Sci 2017, 8 (1), 395–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Li A; Yadav R; White JK; Herroon MK; Callahan BP; Podgorski I; Turro C; Scott EE; Kodanko JJ Illuminating Cytochrome P450 Binding: Ru(II)-Caged Inhibitors of CYP17A1. Chem. Commun 2017, 53 (26), 3673–3676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Zamora A; Denning CA; Heidary DK; Wachter E; Nease LA; Ruiz J; Glazer EC Ruthenium-containing P450 Inhibitors for Dual Enzyme Inhibition and DNA Damage. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 2165–2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Zayat L; Calero C; Albores P; Baraldo L; Etchenique R A New Strategy for Neurochemical Photodelivery: Metal-Ligand Heterolytic Cleavage. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125 (4), 882–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Nikolenko V; Yuste R; Zayat L; Baraldo LM; Etchenique R Two-Photon Uncaging of Neurochemicals Using Inorganic Metal Complexes. Chem. Commun 2005, (13), 1752–1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Zayat L; Salierno M; Etchenique R Ruthenium(II) Bipyridyl Complexes as Photolabile Caging Groups for Amines. Inorg. Chem 2006, 45 (4), 1728–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Zayat L; Filevich O; Baraldo LM; Etchenique R Ruthenium Polypyridyl Phototriggers: from Beginnings to Perspectives. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci 2013, 371, 20120330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).San Miguel V; Alvarez M; Filevich O; Etchenique R; del Campo A Multiphoton Reactive Surfaces Using Ruthenium(II) Photocleavable Cages. Langmuir 2011, 28 (2), 1217–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Salierno M; Marceca E; Peterka DS; Yuste R; Etchenique R A Fast Ruthenium Polypyridine Cage Complex Photoreleases Glutamate with Visible or IR Light in One and Two Photon Regimes. J. Inorg. Biochem 2010, 104 (4), 418–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Fino E; Araya R; Peterka DS; Salierno M; Etchenique R; Yuste R RuBi-Glutamate: Two-Photon and Visible-Light Photoactivation of Neurons and Dendritic Spines. Front. Neural. Circuits. 2009, 3, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Li A; Turro C; Kodanko JJ Ru(II) Polypyridyl Complexes as Photocages for Bioactive Compounds Containing Nitriles and Aromatic Heterocycles. Chem. Commun 2018, 54 (11), 1280–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Cabrera R; Filevich O; Garcia-Acosta B; Athilingam J; Bender KJ; Poskanzer KE; Etchenique R A Visible-Light-Sensitive Caged Serotonin. ACS Chem. Neurosci 2017, 8 (5), 1036–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Pereira Ade C; Ford PC; da Silva RS; Bendhack LM Ruthenium-Nitrite Complex as Pro-Drug Releases NO in a Tissue and Enzyme-Dependent Way. Nitric Oxide 2011, 24 (4), 192–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Petruzzella E; Braude JP; Aldrich-Wright JR; Gandin V; Gibson D A Quadruple-Action Platinum(IV) Prodrug with Anticancer Activity Against KRAS Mutated Cancer Cell Lines, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl, 2017, 56, 11539–11544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Bonnet S Why Develop Photoactivated Chemotherapy? Dalton Trans. 2018, 47 (31), 10330–10343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Goldbach RE; Rodriguez-Garcia I; van Lenthe JH; Siegler MA; Bonnet S N-acetylmethionine and Biotin as Photocleavable Protective Groups for Ruthenium Polypyridyl Complexes. Chem. Eur. J 2011, 17 (36), 9924–9929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Respondek T; Garner RN; Herroon MK; Podgorski I; Turro C; Kodanko JJ Light Activation of a Cysteine Protease Inhibitor: Caging of a Peptidomimetic Nitrile with Ru(II)(bpy)2. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133 (43), 17164–17167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Mosquera J; Sanchez MI; Mascarenas JL; Eugenio Vazquez M Synthetic Peptides Caged on Histidine Residues with a Bisbipyridyl Ruthenium(II) Complex that can be Photolyzed by Visible Light. Chem. Commun 2015, 51 (25), 5501–5504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Wachter E; Heidary DK; Howerton BS; Parkin S; Glazer EC Light-Activated Ruthenium Complexes Photobind DNA and are Cytotoxic in the Photodynamic Therapy Window. Chem. Commun 2012, 48 (77), 9649–9651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Howerton BS; Heidary DK; Glazer EC Strained Ruthenium Complexes Are Potent Light-Activated Anticancer Agents. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134 (20), 8324–8327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Wachter E, Howerton BS, Hall EC, Parkin S, Glazer EC A New Type of DNA “Lght Switch”: a Dual Photochemical Sensor and Metalating Agent for Duplex and G-Quadruplex DNA. Chem. Commun 2014, 50 (3), 311–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Hidayatullah AN; Wachter E; Heidary DK; Parkin S; Glazer EC Photoactive Ru(II) Complexes with Dioxinophenanthroline Ligands are Potent Cytotoxic Agents. Inorg. Chem 2014, 53 (19), 10030–10032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Van Houten J, Watts RJ Temperature Dependence of the Photophysical and Photochemical Properties of the Tris(2,2′-bipyridyl)ruthenium(II) Ion in Aqueous Solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1976, 98 (16), 4853–4858. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Durham B; Caspar JV; Nagle JK; Meyer TJ Photochemistry of Ru(bpy)32+. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1982, 104 (18), 4803–4810. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Ford PC The Ligand-Field Photosubstitution Reactions of D6 Hexacoordinate Metal-Complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev 1982, 44 (1), 61–82. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Havrylyuk D; Deshpande M; Parkin S; Glazer EC Ru(II) complexes with Diazine Ligands: Electronic Modulation of the Coordinating Group Is Key to the Design of “Dual Action” Photoactivated Agents. Chem. Commun 2018, 54 (88), 12487–12490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).While imidazole systems can be easily synthesized, we found the photoreactivity to be too low for many applications.

- (34).Knoll JD; Albani BA; Durr CB; Turro C Unusually Efficient Pyridine Photodissociation from Ru(II) Complexes with Sterically Bulky bBidentate Ancillary Ligands. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118 (45), 10603–10610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Hecker CR; Fanwick PE; McMillin DR Evidence for Dissociative Photosubstitution Reactions of [Ru(trpy)(bpy)(NCCH3)]2+. Crystal and Molecular Structure of [Ru(trpy)(bpy)(py)](PF6)2·(CH3)2CO. Inorg. Chem 1991, 30 (4), 659–666. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Crutchley RJ; Lever ABP Comparative Chemistry of Bipyrazyl and Bipyridyl Metal Complexes: Spectroscopy, Electrochemistry, and Photoanation. Inorg. Chem 1982, 21 (6), 2276–2282. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Vicendo P; Mouysset S; Paillous N Comparative Study of Ru(bpz)3(2+) Ru(bipy)3(2+) and Ru(bpz)2Cl2 as Photosensitizers of DNA Cleavage and Adduct Formation. Photochem. Photobiol 1997, 65 (4), 647–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Vu AT; Santos DA; Hale JG; Garner RN Tuning the Excited State Properties of Ruthenium(II) Complexes with a 4-substituted Pyridine Ligand. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2016, 450, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Sun W; Wen Y; Thiramanas R; Chen M; Han J; Gong N; Wagner M; Jiang S; Meijer MS; Bonnet S; Butt H-J; Mailander V; Liang X-J; Wu S Red-Light-Controlled Release of Drug–Ru Complex Conjugates from Metallopolymer Micelles for Phototherapy in Hypoxic Tumor Environments. Adv. Funct. Mater 2018, 28, 1804227. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Sun W; Thiramanas R; Slep LD; Zeng X; Mailander V; Wu S; Photoactivation of Anticancer Ru Complexes in Deep Tissue: How Deep Can We Go? Chem.: Eur. J 2017, 23, 10832–10837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Chen Z; Sun W; Butt HJ; Wu S Upconverting-Nanoparticle-Assisted Photochemistry Induced by Low-Intensity Near-Infrared Light: How Low Can We Go? Chem.: Eur. J 2015, 21, 9165–9170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Albani BA; Durr CB; Turro C Selective Photoinduced Ligand Exchange in a New Tris-Heteroleptic Ru(II) Complex. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 13885–13892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Loftus LM; White JK; Albani BA; Kohler L; Kodanko JJ; Thummel RP; Dunbar KR; Turro C New RuII Complex for Dual Activity: Photoinduced Ligand Release and 1O2 Production. Chem.: Eur. J 2016, 22, 3704–3708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Woods JJ; Cao J; Lippert AR; Wilson JJ Characterization and Biological Activity of a Hydrogen Sulfide-Releasing Red Light-Activated Ruthenium(II) Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 12383–12387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Lameijer LN; Ernst D; Hopkins SL; Meijer MS; Askes SHC; Le Devedec SE; Bonnet S A Red-Light-Activated Ruthenium-Caged NAMPT Inhibitor Remains Phototoxic in Hypoxic Cancer Cells, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2017, 56, 11549–11553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Havrylyuk D; Heidary DK; Nease L; Parkin S; Glazer EC Photochemical Properties and Structure–Activity Relationships of RuII Complexes with Pyridylbenzazole Ligands as Promising Anticancer Agents. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2017, 2017 (12), 1687–1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Ashby MT Inverse Relationship Between the Kinetic and Thermodynamic Stabilities of the Misdirected Ligand Complexes Delta/Lambda-(Delta/Lambda-1,1′-Biisoquinoline)Bis(2,2′-Bipyridine)Metal(II) (Metal=Ruthenium, Osmium). J. Am. Chem. Soc 1995, 117, 2000–2007. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Cuello-Garibo JA; Meijer MS; Bonnet S To Cage or to Be Caged? The Cytotoxic Species in Ruthenium-Based Photoactivated Chemotherapy is Not Always the Metal, Chem. Commun 2017, 53, 6768–6771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Azar DF; Audi H; Farhat S; El-Sibai M; Abi-Habib RJ; Khnayzer RS Phototoxicity of Strained Ru(II) Complexes: Is it the Metal Complex or the Dissociating Ligand? Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 11529–11532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Mansour N; Mehanna S; Mroueh M,A; Audi H; Bodman-Smith K; Daher CF; Taleb RI; El-Sibai M; Khnayzer RS Photoactivatable Ru(II) Complex Bearing 2,9-Diphenyl-1,10-phenanthroline: Unusual Photochemistry and Significant Potency on Cisplatin-Resistant Cell Lines. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2018, 2524–2532. [Google Scholar]

- (51).While recent reports have highlighted the cytotoxicity of some of the bidentate ligands used here, our HPLC analysis does not show any ejection of the bidentate ligand.

- (52).Mobian P; Kern JM; Sauvage JP Light-Driven Machine Prototypes Based on Dissociative Excited States: Photoinduced Decoordination and Thermal Recoordination of a Ring in a Ruthenium(II)-Containing [2]catenane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2004, 43, 2392–2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Xie C; Sun W; Lu H; Kretzschmann A; Liu J; Wagner M; Butt HJ; Deng X; Wu S Reconfiguring Surface Functions Using Visible-Light-Controlled Metal-Ligand Coordination. Nat. Commun 2018, 9, 3842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Rapp TL; Wang Y; Delessio MA; Gau MR; Dmochowski IJ Designing photolabile ruthenium polypyridyl crosslinkers for hydrogel formation and multiplexed, visible-light degradation. RSC Advances. 2019, 9 (9), 4942–4947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Monro S; Colon KL; Yin H; Roque J 3rd; Konda P; Gujar S; Thummel RP; Lilge L; Cameron CG; McFarland SA Transition Metal Complexes and Photodynamic Therapy from a Tumor-Centered Approach: Challenges, Opportunities, and Highlights from the Development of TLD1433. Chem. Rev 2019, 119 (2), 797–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.