Abstract

IRGM1 is recognized as a master regulator of type I interferon responses against pathogens, while also protecting against autoimmune diseases. It has now been shown that IRGM1 controls autoinflammatory responses by modulating mitophagy flux.

IRGM1 plays an essential role in the type I interferon (IFN-I) responses against several intracellular pathogens1. IRGM1 supports host defense by promoting the fusion of phagosomes with lysosomes and modifying endomembrane dynamics during infection2. IRGM1 has also been connected with mitochondrial autophagy (mitophagy)3, probably due to the alterations to endomembrane trafficking. When mitophagy is defective, mitochondrial components can escape the organelle and act as danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). DAMPs, such as mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), act as danger signals that are recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) to activate inflammatory signaling and cytokine secretion from immune and non-immune cells4,5. A new study by Rai et al.6 demonstrates that IRGM1 regulates mitophagy flux to control immune signaling through cell type–specific mechanisms that impact innate immune responses and the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases6.

IFN-γ is a pleiotropic immunomodulatory cytokine that functions, at least in part, by modulating immunity-related GTPase (IRG) proteins. All of the IRG family members are required for the destruction of mycoplasma, but only IRGM1 is required to protect against a broad range of pathogens7. The role of IRGM1 in pathogen defense involves destroying intracellular bacteria and promoting the survival of phagocytic myeloid cells during infection8. Furthermore, IRGM1 deficiency is associated with a wide range of autoimmune diseases3. However, differential intracellular localization of IRGM1 splicing isoforms, with the long form on endolysosomes and the short form on Golgi and mitochondria, may indicate a broader role for IRGM1, both in the clearance of pathogens9 and in the mitochondrial quality control process.

Multiple receptors have been reported to recognize mtDNA. For instance, mtDNA can be detected by endosomal Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9), which activates the MyD88–NF-κB pathway to trigger the expression and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin (IL)-6 via IFN-stimulated gene (ISG) upregulation5. mtDNA can also be recognized in the cytoplasm by AIM2 or NLRP3 inflammasomes, which induce caspase-1-mediated proteolytic cleavage of pro-IL-1β to produce its mature and secreted form10, and by cyclic GMP–AMP synthase (cGAS), which activates stimulator of interferon genes (STING) to increase IFN-I secretion and ISG expression11. In concordance with this concept, defective mitophagy has been associated with increased IFN-I through the activation of the cGAS–STING pathway12 and the activation of NLRP3 and IL-1β production after mitochondrial stress13. Interestingly, Rai et al. found that IRGM1 deficiency alone may be sufficient to promote the release of mitochondrial DAMPs, which stimulate IFN-I responses.

Further investigation of the cellular response to IRGM1 deficiency suggested that stromal and immune cells may respond differently to IFN-I signaling. Rai et al. provide evidence that IRGM1-deficient cells in vitro activate downstream IFN-I through distinct DNA or RNA sensors in stromal and immune cells. Following IFN-γ stimulation, both fibroblasts and macrophages exhibit an IFN-I phenotype. As previously demonstrated for various cell lines3, IRGM1 suppresses the cytoplasmic activation of cGAS–STING signaling induced by cytosolic mtDNA in fibroblasts. Defects in mitophagic flux due to lysosomal dysfunction mediate this process.

However, the mechanisms by which IRGM1 protects against IFN-I phenotypes in bone-marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) are different. Importantly, Rai et al. found an absence of cytosolic mtDNA but enhanced lysosomal activity in IRGM1-deficient macrophages. After examining lysosome receptors and confirming the lack of mtDNA signaling through TLR9, they identified the single-stranded-RNA sensor TLR7 as being responsible for IFN-I responses in IRGM1-deficient BMDMs, suggesting mtRNA acts as a mitochondrial DAMP in IRGM1-deficient cells. Moreover, the accumulation of late-stage autophagosomes and lysosomes in IRGM1-deficient BMDMs was stimulated by exposure to IFN-γ. Lysosome accumulation increased the abundance of TLR7 and residual mitochondrial content in the cell. Inhibiting autophagy via phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitors or blocking mitophagy initiation via PTEN-induced kinase (PINK) knockdown reduced the IFN-I phenotype in BMDMs. Together, these data highlight the importance of properly functioning autophagy in BMDMs to eliminate mitochondrial DAMPs from defective mitochondria.

To confirm these processes’ relevance in vivo, Rai et al. tested whether IRGM1 deficiency causes autoimmune tissue damage and autoantibodies through IFN-I and the cGAS–STING pathway. Indeed, damage due to IRGM1 ablation was dependent on the IFN-I receptor, IFNAR1. Consistent with their fibroblast data, Rai et al. found that IRGM1-deficiency-mediated autoimmune tissue damage and autoantibody production were rescued by cGAS or STING ablation, albeit with some differences in penetrance and the extent of the rescue. However, ISG induction by IFN-γ was rescued by STING but not cGAS ablation in BMDMs, consistent with cGAS being necessary for non-immune IFN-I phenotypes in vivo.

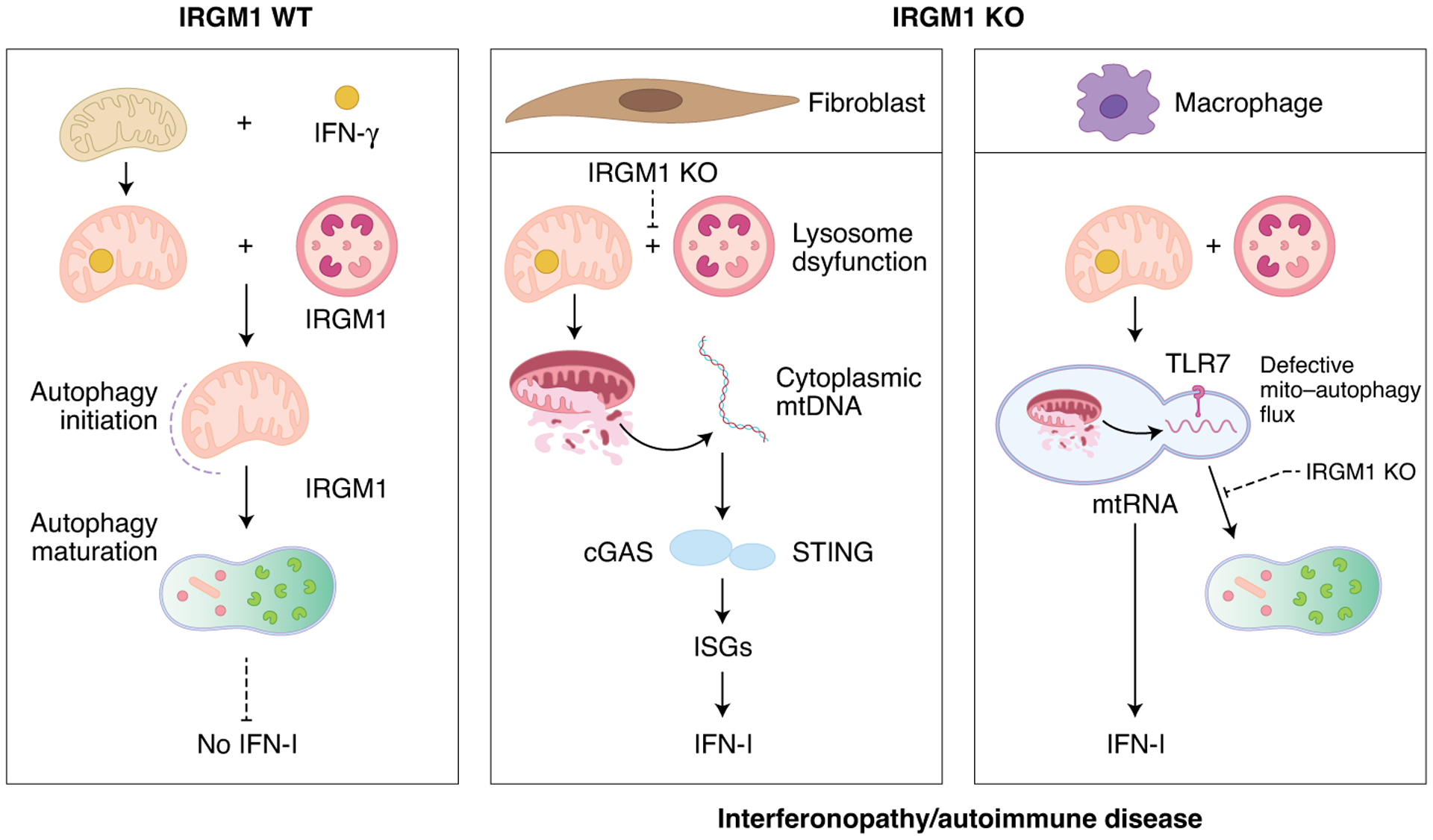

In summary, IRGM1 plays a new role in suppressing mitochondrial DAMP signaling and IFN-I activation in both immune and stromal cells through distinct mechanisms. IRGM1 deficiency promotes lysosome dysfunction in fibroblasts, allowing the cytoplasmic activation of the cGAS–STING pathway through cytosolic mtDNA. In macrophages, IRGM1 supports autophagosome–lysosome fusion to eliminate endosome TLR7 and mtRNA (Fig. 1). The diversity of phenotypes among immune and stromal cells with IRGM1 deficiency may be due to differential expression or cell-type-dependence of downstream DNA-induced signaling pathways. For example, differences in the expression of TLR7 versus cGAS could alter which pathway is selected. Likewise, interactions between cytosolic and endosomal nucleic acid–sensing receptors may also be responsible for the diverse autoimmune phenotypes observed in IRGM1-deficient mice.

Fig. 1 |. Irgm1 controls mitochondrial DamP signaling and IFN-I activation through distinct pathways in somatic and immune cells.

In the presence of IRGM1, damaged and IFN-γ-stressed mitochondria are removed by mitophagy, protecting against mitochondrial DAMP–induced interferonopathy and autoinflammatory responses. IRGM1 deficiency in fibroblasts promotes lysosome dysfunction, allowing the cytoplasmic activation of the cGAS–STING pathway by cytosolic mtDNA. By contrast, in bone-marrow-derived macrophages, IRGM1 promotes autophagosome–lysosome fusion to suppress the activation of endosomal TLR7 by mitochondrial DAMPs.

Although the study by Rai et al. has advanced our understanding of the mechanisms by which IRGM1 modulates mitophagy and suppresses IFN-I responses, it also raises additional questions. The mechanisms involved in IRGM1 modulation of mitochondrial stress are unclear. Hyperactivity of interferon signaling in the context of IRGM1 deficiency may be sufficient to induce both mitochondrial dysfunction and to obstruct mitophagy flux. Indeed, IFN-γ has been shown to cause mitochondrial dysfunction. In addition to regulating mitophagy, IRGM1 also modulates mitochondrial fission and metabolism14,15, supporting the possibility that IRGM1 plays multiple roles in mitochondrial homeostasis. Another question that follows from this work is how IRGM1 differentially regulates lysosomal function versus autophagosome–lysosome fusion in stromal and immune cells. In addition, this study found no requirement for the antiviral protein MAVS in the TLR7 signaling cascade, as previously reported, suggesting further research into TLR7’s role and signaling pathways is needed3. Although further exploration is needed to better understand the cross-regulation of nucleic acid sensors in different cell types, the study by Rai et al. provides strong evidence that mitochondrial DAMPs actively participate in innate immune responses and that IRGM1 is a master gatekeeper of mitochondria-induced autoinflammatory responses.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Azzam KM et al. JCI Insight 2, e91914 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tiwari S, Choi H-P, Matsuzawa T, Pypaert M & MacMicking JD Nat. Immunol 10, 907–917 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jena KK et al. EMBO Rep. 21, e50051 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodríguez-Nuevo A & Zorzano A Cell Stress 3, 195–207 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riley JS & Tait SW G. EMBO Rep 21, e49799 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rai P et al. Nat. Immunol 10.1038/s41590-020-00859-0 (2021). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunn JP & Howard JC PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001008 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor GA et al. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008553 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Springer HM, Schramm M, Taylor GA & Howard JC J. Immunol 191, 1765–1774 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathur A, Hayward JA & Man SM J. Leukoc. Biol 103, 233–257 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.West AP & Shadel GS Nat. Rev. Immunol 17, 363–375 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sliter DA et al. Nature 561, 258–262 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li H et al. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev 2016, 1987149 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt EA et al. J. Biol. Chem 292, 4651–4662 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henry SC, Schmidt EA, Fessler MB & Taylor GA PLoS ONE 9, e95021 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]