Abstract

Purpose

Pupillary responses captured via pupillometry (measurement of pupillary dilation and constriction during the performance of a cognitive task) are psychophysiological indicators of cognitive effort, attention, arousal, and resource engagement. Pupillometry may be a promising tool for enhancing our understanding of the relationship between cognition and language in people with and without aphasia. Interpretation of pupillary responses is complex. This study was designed as a stepping-stone for future pupillometric studies involving people with aphasia. Asking comprehension questions is common in language processing research involving people with and without aphasia. However, the influence of comprehension questions on pupillometric indices of task engagement (tonic responses) and cognitive effort (task-evoked responses of the pupil [TERPs]) is unknown. We tested whether asking comprehension questions influenced pupillometric results of adults without aphasia during a syntactic processing task.

Method

Forty adults without aphasia listened to easy (canonical) and difficult (noncanonical) sentences in two conditions: one that contained an explicit comprehension task (question condition) and one that did not (no-question condition). The influence of condition and canonicity on pupillary responses was examined.

Results

The influence of canonicity was only significant in the question condition: TERPs for difficult sentences were larger than TERPs for easy sentences. Tonic responses did not differ between conditions.

Conclusions

Although participants had similar levels of attentiveness in both conditions, increases in indices of cognitive effort during syntactic processing were significant only when participants expected comprehension questions. Results contribute to a body of evidence indicating the importance of task design and careful linguistic stimulus control when using pupillometry to study language processing.

Supplemental Material

Pupillometry—the measurement of pupil dilation and constriction during the performance of a cognitive task—has been used for decades to index cognitive effort (Beatty & Lucero-Wagoner, 2000; Laeng et al., 2007; Sirois & Brisson, 2014). The construct of cognitive effort is typically conceptualized as an intensity dimension of processing, associated with the cognitive constructs of working memory, attention, and resource allocation (Just & Carpenter, 1993; Kahneman, 1973). As such, pupillometric responses are considered psychophysiological indicators of cognitive effort, attention, arousal, and task engagement (Murphy et al., 2014; Unsworth & Robison, 2015).

The ability to capture the complexities of cognitive processing makes pupillometry a promising tool for enhancing our understanding of the relationship between cognition and language in people with and without cognitive–linguistic impairments. Pupillometry may be particularly useful for studying the link between language and cognitive impairments in people with aphasia (PWA). While aphasia is defined as a language impairment, PWA also tend to exhibit deficits in cognitive domains, such as attention (McNeil et al., 2011; Murray, 2012), working memory (H. H. Wright & Fergadiotis, 2012), and arousal (Sandberg, 2017). Additionally, PWA tend to exhibit greater variability in performance on language and cognitive tasks relative to people without aphasia (McNeil et al., 2011; Villard & Kiran, 2015). Pupillometry has been shown to be an ideal tool for exploring factors that lead to inter- and intraindividual variability (Wagner et al., 2019).

Interpretation of pupillometric responses can be complex. There are myriad sources of inter- and intraindividual heterogeneity that may influence pupillometric responses, particularly in PWA, that can be difficult to document, let alone control. There are, however, sources of variability under the experimenter's control in pupillometric studies: those related to experimental design. Factors such as stimulus difficulty, task instructions, and response requirements have all been shown to influence pupillometric responses (Ben-Nun, 1986; Reinhard et al., 2007; Richer & Beatty, 1985; Schluroff, 1982; P. Wright & Kahneman, 1971). It is important that experimental tasks be designed to focus the participants' attention on critical aspects of the stimuli under study while minimizing task components that may elicit confounding pupillometric responses.

The feasibility of using pupillometry with PWA has been demonstrated (Chapman & Hallowell, 2015; Haghighi & Hallowell, 2017, 2019). Still, to further the development of robust pupillometric methods to be applied in studies involving PWA, this study is designed to examine factors related to experimental design that influence pupillometric responses during language processing tasks in people without aphasia. This study is intended as a stepping-stone toward the study of aphasia; as such, we used a task that has well-established relevance to the study of aphasia: syntactic processing. There is ample evidence that greater syntactic difficulty evokes greater cognitive effort, as indexed by pupillometric responses (described below). However, we do not know the influence of a common component of syntactic processing tasks: the asking of comprehension questions. Comprehension questions may be useful for eliciting and/or verifying task engagement. However, expecting questions might change how participants process linguistic stimuli in a way that confounds pupillometric results related to syntactic difficulty. Therefore, in the current study, we examined whether the inclusion of comprehension questions would influence engagement and cognitive effort during a syntactic processing task, as indexed by pupillometric responses, in individuals without aphasia. Results are intended to provide an evidence base for the design of future pupillometric studies and to enable a clearer interpretation of pupillometric responses to syntactic processing tasks in people with and without aphasia.

Pupillometric Measures

Two types of pupillometric measures have been used in the literature to index cognitive effort and task engagement: phasic and tonic. Each is important to consider in the context of this study and will be described here.

Phasic Measures

Pupillometry is most commonly used to index cognitive effort in response to a task. Phasic or task-evoked responses of the pupil (TERPs) quantify the change in pupil diameter as an individual is engaged in a cognitive task. TERPs are driven by activity in the locus coeruleus (LC), a small cluster of neurons in the brainstem. The LC is the sole source of norepinephrine (NE) to the cortex (Samuels & Szabadi, 2008). LC-NE activity has been implicated in a variety of cognitive processes (Usher et al., 1999) and to corresponding changes in pupil diameter (Alnæs et al., 2014; Murphy et al., 2014, 2011; Rajkowski et al., 2004).

TERPs are a continuous measure of cognitive activity. The onset of a cognitively demanding task leads to an increased firing rate in the LC-NE system (Smallwood et al., 2012; Usher et al., 1999), which inhibits the parasympathetic pathway responsible for pupillary constriction, resulting in pupil dilation (Steinhauer et al., 2004). The magnitude of TERPs is an index of the intensity of processing related to cognitive demand (Just & Carpenter, 1993; Kahneman, 1973; Unsworth & Robison, 2015). More difficult tasks elicit larger TERPs than easier tasks; this difficulty effect has been robustly evidenced across a variety of tasks and cognitive domains (for reviews, see Beatty & Lucero-Wagoner, 2000; Laeng et al., 2007; Sirois & Brisson, 2014) and can reflect both within-task and between-tasks difficulty.

Tonic Measures

Tonic pupillary measures correspond to baseline levels of LC functioning and are typically measured in periods of rest during a cognitive task. They can be used to gauge individuals' overall levels of alertness and preparedness for task engagement (Gilzenrat et al., 2010; Unsworth & Robison, 2017). Low levels of LC-NE functioning (smaller tonic pupil measures) are related to drowsiness and inattentiveness, whereas high levels (larger tonic pupil measures) are associated with distractibility. Intermediate levels are said to be ideal for supporting task performance (Smallwood et al., 2012). Tonic measures are sometimes referred to as “baseline” measures, as they are often collected during a period of relative inactivity (e.g., between presentations of experimental stimuli). Along with being analyzed independently, as noted above, baseline measures are often used to calculate TERPs.

Pupillometry and Aphasia

Benefits

Cognitive challenges are well documented in PWA (Murray, 2012, 2017; H. H. Wright & Fergadiotis, 2012), yet the complex relationships between deficits in language and cognition remain poorly understood (Villard & Kiran, 2016). Pupillometric responses, as psychophysiological indicators of cognitive performance in domains such as attention, working memory, arousal, and effort, offer a unique tool with which to examine those relationships. Pupillometric measures of cognitive effort may be an invaluable resource in terms of identifying inter- and intraindividual cognitive differences that characterize PWA (McNeil et al., 2011; Murray, 2012; H. H. Wright & Fergadiotis, 2012). As Wagner et al. (2019) affirm, pupillometry enables the concurrent study of several factors that contribute to individual differences: “… (a) participants' response to a task, (b) their momentary state of mind (i.e., their emotional and attentional state), and (c) their cognitive capacity” (p. 2).

Additional important benefits of pupillometric measures are that they enable the real-time measurement of continuous processing, are outside of participants' conscious control, and do not require an overt behavioral response. Not requiring an overt behavioral response is particularly beneficial for individuals with language impairments, including aphasia, as PWA often exhibit concomitant motor impairments that may confound their performance. For PWA, pointing, gesturing, speaking, key pressing, and following commands may all be confounded by challenges with motor programming and neuromuscular innervation and coordination; when relying on such response types, response inaccuracy or a lack of response may invalidate the intended measures of cognitive–linguistic abilities under study.

Feasibility

Pupillometry has been applied only rarely in research and clinical investigations of language processing in individuals with language impairment, despite myriad potential benefits. We first demonstrated the feasibility of using pupillometric measures to study language processing in PWA (Chapman & Hallowell, 2015). PWA (n = 39) as well as age- and education-matched controls (n = 40) listened to easy and difficult single nouns while viewing matched images. In both groups, difficult nouns elicited greater TERPs than easy nouns. There was no significant difference between groups; this was not surprising, as single-word processing abilities were relatively preserved in the sample of PWA. That study provided the first evidence of the feasibility of using pupillometry to study cognitive effort in linguistic processing (at least at the single-noun level) in PWA. Additional studies have since examined the use of pupillometry to study noun and sentence processing, as well as short-term memory, in PWA (Chapman & Hallowell, 2016, 2019; Dinh & Hallowell, 2015; Haghighi & Hallowell, 2015, 2019; Kim et al., 2018).

Developing Pupillometric Methods for the Study of Aphasia: A Focus on Syntax

A robust body of evidence indicates that processing noncanonical sentences is more difficult than processing canonical ones; this distinction holds for people of all ages, with and without aphasia and other language disorders (Bahlmann et al., 2007; Meyer et al., 2012; Montgomery & Evans, 2009; Thompson & Shapiro, 2005; Traxler et al., 2002). Not surprisingly, a pupillometric syntactic difficulty effect has been demonstrated in people without language impairments; syntactically complex sentences lead to larger TERPs than relatively simpler sentences (Ayasse & Wingfield, 2018; Haghighi & Hallowell, 2015; Just & Carpenter, 1993; Piquado et al., 2010; Schluroff, 1982). While PWA have well-documented impairments in processing syntax (Caplan et al., 2007; Clark, 2011), no pupillometric studies have been undertaken to examine the potential cognitive underpinnings of these deficits.

A syntactic processing task was chosen for this study for three reasons. First, as stated above, syntactic processing tasks are important in the study of aphasia, especially given common syntactic impairments in PWA. Second, the influence of syntactic difficulty on language processing and comprehension is well understood, at least in populations without language impairments. That is, we expect to find a syntactic difficulty effect (i.e., greater syntactic difficulty evokes greater cognitive effort); therefore, our hypotheses can be directed toward experimental design issues beyond linguistic stimulus manipulation. Third, PWA tend to perform variably on syntactic processing, especially as task demands vary (Caplan et al., 2006; Salis & Edwards, 2009); thus, methods that will help study the nature of that variability are needed. Prior to examining syntactic processing using pupillometry in PWA, however, it is vital to gain increased understanding of the influence of experimental design on task engagement and cognitive effort in the absence of aphasia.

Comprehension Questions in Syntactic Processing Tasks

In behavioral and pupillometric studies of syntactic processing, comprehension questions are often a component of the experimental task. Accuracy of responses to those questions is commonly used to ensure that participants were actively engaged in syntactic processing and to check the accuracy of processing. In the context of a pupillometric study of cognitive effort associated with syntactic processing, however, it is unknown whether or not comprehension questions are necessary to elicit a pupillometric syntactic difficulty effect and whether asking questions might potentially confound pupillometric results. To measure cognitive effort related to syntactic difficulty, is it necessary to include comprehension questions, or is simply presenting participants with sentences that vary in syntactic complexity sufficient?

Components of any experimental task should focus the participants' attention on critical aspects of the stimuli under study while minimizing task components that may elicit confounding pupillometric responses. Indeed, the way that cognitive responses are elicited may change the cognitive underpinnings of the task; linguistic performance is rarely tested in a process-pure manner (Campbell et al., 2016). In studies of syntactic processing, task engagement and cognitive effort, indexed via pupillometric responses, should be driven primarily by syntactic manipulations and minimally by any additional effort required to prepare a response and then answer questions. Any additional effort may conflate the effort elicited by the linguistic stimuli themselves, particularly in a clinical population with concomitant impairments.

The case for removing comprehension questions in pupillometric studies of syntactic processing. In behavioral studies, accuracy ratings determined by responses to comprehension questions are often used to index syntactic processing ability in PWA. However, as noted earlier, overt responses (e.g., pointing, speaking) may be unreliable or invalid due to concomitant impairments in motor and visual processing. Furthermore, syntactic processing deficits in PWA may be linked to underlying cognitive challenges (e.g., with attention and working memory) that are variable. If this is the case, indexing online processing via binary comprehension responses (correct, incorrect) that occur postprocessing may be inadequate and unnecessary.

Removing comprehension questions and simply presenting participants with stimuli to process may also remove aspects of experimental design that induce variability unrelated to the cognitive construct under study (in this case, cognitive effort associated with syntactic processing). For example, the simple act of performing a motor response can influence TERPs (Reinhard et al., 2007). Furthermore, the preparation for a motor response may influence TERPs, even when no overt response is required (Moresi et al., 2008; Richer & Beatty, 1985; Richer et al., 1983). In addition, the influence of motor impairments, common in PWA, on TERPs is unknown, so removing them may be the best course of action. As mentioned previously, one of the benefits of pupillometry is that it does not require an overt behavioral response to index cognitive effort.

The case for keeping comprehension questions in pupillometric studies of syntactic processing. Despite the potential drawbacks described above, comprehension questions may be essential for ensuring that the participants' focus of attention is on processing of linguistic stimuli. That is, the presence of comprehension questions may add some incentive, motivation, and accountability for engaging actively in syntactic processing. Without questions, a participant may engage in mind-wandering and not even attend to the task, and the experimenter might not know it. Alternatively, without questions, participants might merely engage in “good enough” processing rather than attentive, engaged processing. According to the theory of good-enough processing, the linguistic processing system's responsibility is to create a linguistic representation that is sufficient to accomplish the task at hand (Ferreira et al., 2002; Ferreira & Patson, 2007). Good-enough processing occurs in the natural use of language, enabling one to speak and comprehend others' speech at the same time. If the initial shallow parsing of a sentence is plausible, one is unlikely to engage in deeper processing.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to gain a better understanding of how the anticipation of comprehension questions influences engagement (indexed via tonic pupillary responses) and cognitive effort (indexed via TERPs) in a syntactic processing task in individuals without aphasia. Pupillometric responses were continuously collected during two conditions of a syntactic processing task in a group of adults without aphasia. In the no-question condition, individuals simply listened to canonical (easy) and noncanonical (difficult) sentences. In the question condition, individuals listened to the same sentence types but were instructed that they would occasionally hear and be expected to answer a comprehension question. In both conditions, tonic pupil responses, measured during times of rest between stimuli, were calculated as indicators of task engagement and arousal. TERPs (changes in pupil diameter timed relative to the onset of a cognitive task) were calculated as indicators of cognitive effort. Results are intended to provide an evidence base to support the design of future pupillometric studies and to enable clearer guidance for the interpretation of pupillometric responses to syntactic processing tasks in people with and without aphasia.

We asked two research questions.

What is the effect of condition (no-question, question) on the participants' overall level of arousal or task engagement, as indicated by changes in tonic pupillary responses? We expected that participants would attend to the syntactic processing task in both conditions, regardless of whether there were questions, as people tend to process spoken language readily, especially in the absence of distraction (Shtyrov, 2010). As such, we did not anticipate differences in tonic pupillary responses between conditions.

What is the effect of condition (no-question, question) and canonicity (canonical, noncanonical) on indices of cognitive effort, as indicated via TERPs? Supported by literature noted above, we anticipated a significant effect of canonicity (a syntactic difficulty effect) in both conditions. That is, across both conditions, noncanonical sentences would elicit larger TERPs (e.g., greater levels of cognitive effort) than canonical sentences. However, if individuals were less engaged in processing during the no-question condition, the magnitude of the effect of canonicity may be reduced. In the question condition, only TERPs from trials that did not actually contain a question were included in analyses. Therefore, we were measuring changes in cognitive effort in response to the anticipation of a comprehension question rather than indexing changes related to the preparation and/or performance of the motor task of responding.

Method

Participants

Forty participants (28 women, 12 men; age: M = 28.90 years, SD = 6.11, range: 20–39; years of education: M = 18.13, SD = 2.43, range: 13–22) were recruited in the vicinity of Athens, Ohio, via distribution and posting of flyers at community agencies and throughout the Ohio University campus, along with e-mail and Facebook announcements. All participants signed consent forms approved by the Ohio University Institutional Review Board. Participants met the following inclusion criteria: status as a native speaker of American English; no reported history of speech, language, learning, or developmental impairment; no reported history of stroke or brain injury; passing scores on a hearing screening (25 dB SPL at frequencies of 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz); passing scores on visual acuity for near vision screening, with (n = 14) or without (n = 26) corrective lenses or glasses (per the LEA SYMBOLS line test; Hyvärinen et al., 1980); and cognitive status within normal limits per the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (Nasreddine et al., 2005; M = 28.42, SD = 1.37, range: 26–30). To index sentence comprehension status, the participants also completed the Sentence Comprehension subtest of the Verb and Sentence Test (VAST; Bastiaanse et al., 2002; M = 39.58, SD = 0.75, range: 37–40). VAST scores were not used for inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The participants completed additional visual screening tasks for descriptive purposes and interpretation based on results (per Hallowell, 2008). Eyes were inspected for any pathological signs (e.g., redness, swelling, asymmetry of pupils, ocular drainage) that may suggest poor eye health and thus lead to unreliable eye-tracking recording. Extraocular motor function screening entailed a smooth pursuit tracking task. Visual attention was screened using a line bisection task. A pupil reflex screening entailed monocular and binocular (alternating eyes) examination using a handheld penlight. Results from all supplemental visual screening tasks were normal for all participants.

Stimuli

The primary indicator of difficulty in this syntactic processing task was canonicity: Noncanonical sentences are more difficult to process than canonical ones. We sampled across sentence types so as to not capture a syntactic difficulty effect with one sentence type without knowing if the results would generalize to another. Eight sentence types were included, grouped into four canonical/noncanonical pairs: unergative/unaccusative, active/passive, subject-cleft/object-cleft, and subject-relative/object-relative. See Table 1 for specific examples of each sentence type used in this study; see Supplemental Material S1 for a complete list of sentences, along with data regarding sentence length. This sentence bank may be useful for future analysis of the most sensitive sentence types.

Table 1.

Canonical and noncanonical sentence types.

| Sentence type | Example sentence |

|---|---|

| Canonical sentences | |

| Unergative | The boy winked. |

| Active | The father lifted the mother. |

| Subject-cleft | It was the boy who lifted the girl. |

| Subject-relative | The father who lifted the girl punched the mother. |

| Noncanonical sentences | |

| Unaccusative | The girl blushed. |

| Passive | The mother was lifted by the father. |

| Object-cleft | It was the girl who the boy lifted. |

| Object-relative | The girl who the father lifted punched the mother. |

Eighty experimental sentences were developed (10 of each type listed above) using strict psycholinguistic control criteria. To enable comparisons across sentence types, the same 10 verbs were used in all transitive sentences (active, passive, subject-cleft, object-cleft, and for the relative clause verb in subject- and object-relative sentences). Ten additional verbs were selected as the matrix verb for relative clause sentences. Verbs were controlled for the following criteria: spoken word frequency and contextual diversity (Brysbaert & New, 2009); age of acquisition and imageability (Bird et al., 2001; School of Psychology, The University of Western Australia, 2015); and number of letters, phonemes, and syllables. Four noun phrases also matched for the above criteria (“the boy,” “the girl,” “the mother,” and “the father”) were utilized. See Supplemental Material S2 for a complete list of verbs, nouns, and associated psycholinguistic data.

Sentences were composed in pairs in which the noun phrases were simply reversed; for example, an active sentence was “The boy hugged the mother,” and its passive counterpart was “The mother was hugged by the boy.” It was not possible to use the same verb for unergative and unaccusative sentence pairs; for those, verbs were matched on frequency and contextual diversity. Sentence length, in terms of number of letters, phonemes, syllables, and words, and auditory duration did not significantly differ between any canonical–noncanonical pair except for active and passive sentences. In previous studies, differences in length have been mitigated by adding filler items to equate sentence length (e.g., Ivanova & Hallowell, 2012). This was not done in the current study for two reasons. First, only the active and passive sentences would require the addition of fillers, making these sentences stand out from the other sentence pairs. Second, findings to date are equivocal regarding the influence of sentence length on cognitive effort. There is evidence that longer sentences require more cognitive effort to process; this may be particularly true for older participants (Piquado et al., 2010). However, Schluroff (1982) found that TERPs correlated more strongly with measures of grammatical complexity than length, whereas the participants' subjective rating of difficulty correlated more strongly with length than grammatical complexity.

Sixteen additional sentences (two of each type) were developed to be used in the question condition; these sentences matched all criteria discussed above. Comprehension questions were yes/no questions designed to probe the agent of the sentence. For example, for the sentence “It was the boy who guarded the girl,” the corresponding comprehension question was “Did the girl guard?” Half of the questions heard by the participants had a “yes” answer, whereas the other half had a “no” answer. Stimuli were recorded by an adult male native speaker of American English in a sound-treated booth using a microphone connected to a PC. The average speaking rate over all of the sentences was 3.96 syllables per second (SD = 0.44).

Procedure

The participants first completed informed consent, followed by health, hearing, vision, and cognitive screenings. Then, the participants completed both conditions of the pupillometric sentence-processing tasks. Finally, they completed the Sentence Comprehension subtest of the VAST. The overall duration of the study ranged from 45 min to 1 hr.

Pupillometric Tasks

We used an auditory-only task to minimize the influence of visual stimuli on pupillary responses and cognitive processes (Verney et al., 2001). The participants listened to sentences as they maintained gaze on a fixation point on a computer screen approximately 24–26 in. from their eyes to prevent the accommodation reflex (Loewenfeld & Lowenstein, 1993). The participants completed a syntactic processing task in two conditions: one without comprehension questions (the no-question condition) and one with comprehension questions (the question condition).

To rule out the possibility of specific sentences and/or questions influencing results, the participants were exposed to two different sentence groupings. Odd-numbered participants heard 40 experimental sentences in the no-question condition and then 40 different experimental sentences (plus eight sentences followed by questions) in the question condition. Sentence groupings for even-numbered participants were reversed; the 40 sentences the odd-numbered participants heard in the no-question condition were presented in the question condition for the even-numbered participants. Sentences heard in the question condition for the odd-numbered participants were presented in the no-question condition for the even-numbered participants.

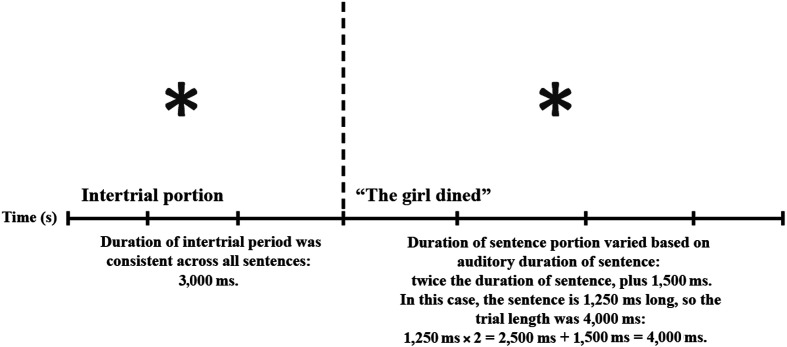

General trial structure. Each trial consisted of two portions: an intertrial portion followed by a sentence portion. The intertrial portion lasted 3 s, during which the participants viewed the fixation point in silence. The sentence portion began with the presentation of the sentence. The length of this portion of the trial was twice the auditory duration of the sentence, plus 1,500 ms. This time window is consistent with other studies that have enabled capturing of processing and comprehension in controls and PWA (Hallowell et al., 2002; Ivanova & Hallowell, 2012). The participants heard a tone at the end of the sentence portion that signified the end of a trial.

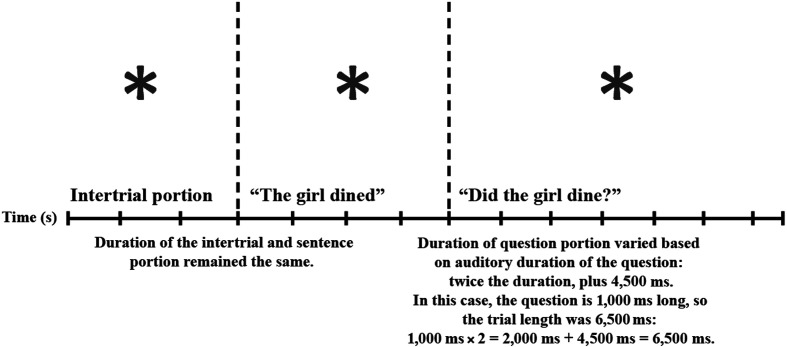

In the question condition, 20% of sentences were followed by comprehension questions that probed the agent of the sentence. These question sentences were quasirandomly distributed throughout the task, with the criteria that half were in the first half of the series of sentences, and the other were in the second half. The duration of question trials differed from that of general trials; three additional seconds were added to the time window between the comprehension question and the beginning of the next trial; this was done to allow ample time for a verbal response and the return of the pupil diameter to baseline. If the participant did not respond to the first question posed, the examiner paused the eye-tracking system and instructed the participant to provide a response to the question. See Figures 1 and 2 for schematics of general and question trials, respectively.

Figure 1.

Schematic depiction of one trial from the sentence-processing task.

Figure 2.

Schematic depiction of one question trial.

No-question condition. The no-question condition was always presented first, to capture TERPs without the participants anticipating questions. Instructions were as follows: “Pay attention to the meaning of each sentence while you look at the image on the screen. It is okay to blink. It is important to pay attention to the meaning of each sentence individually. When you hear a beep, that means it is time to get ready to listen to the next sentence. Please do not talk. Remember, pay attention to the meaning of each sentence individually. You will not be asked to recall the sentences later.” This task lasted approximately 6 min.

Question condition. Following a short break, the participants then completed the question condition. Instructions were as follows: “Pay attention to the meaning of each sentence while you look at the image on the screen. It is important to pay attention to the meaning of each sentence individually. You will not be asked to recall the sentences later, but you will occasionally be asked questions about the sentence you just heard. Please answer them.” This task lasted approximately 8 min.

Instrumentation

The Eyegaze EyeFollower 2.0 remote pupil/corneal reflection system measured binocular pupil movements at a rate of 120 Hz (LC Technologies, 2009). Custom software (Norloff & Cleveland, 2017) was used for stimulus presentation and analysis. Prior to extracting dependent measures, raw pupil data were processed to (a) remove sawtoothing, an artifact not indicative of real pupil behavior that results from alternately sampling each eye; (b) filter out spike samples that result from eye image processing anomalies; and (c) smooth the pupil diameter curves (following the removal of sawtoothing and spike samples).

Dependent Measures

Tonic Response

Tonic pupil measurements were recorded on a trial-by-trial basis by averaging the pupil diameter during the last 500 ms of the intertrial portion, yielding the baseline for each trial that was used in the calculation of phasic responses (see below). They were also analyzed independently as indicators of task engagement (Konishi et al., 2017; Unsworth & Robison, 2015, 2016, 2017).

Phasic Response

The phasic pupillary response, known to be a robust measure of cognitive effort (Beatty & Lucero-Wagoner, 2000), was indexed using mean TERP and was recorded during the sentence portion of each trial. Mean TERPs were calculated via subtraction on a trial-by-trial basis. That is, tonic pupil diameter (mean pupil diameter during the last 500 ms of the intertrial period) was subtracted from the mean pupil diameter during the postsentence time window (see below). This was done on a trial-by-trial basis, because levels of arousal are known to vary over time (Gilzenrat et al., 2010) and because pupil diameter measured during periods of cognitive activity and nonactivity may decrease over the course of the task (Foroughi et al., 2017; Hess & Polt, 1964; Hyönä et al., 1995).

To know whether cognitive effort differs between sentence types, it is important to consider where and when, in the context of auditory sentence presentation, those differences might occur. The time window of analysis has implications for interpreting pupillometric responses (Stanners et al., 1972). Analyses in this study focused on mean TERPs in the postsentential time window, defined as the time between the offset of the sentence and the offset of the trial (refer to Figure 1 for a schematic on timing within each trial). Evidence suggests that the postsentence time window is critical for studying the differences in effort between sentence types (Haghighi & Hallowell, 2017). It is during the postsentence period where the checking and revision of an initial sentence parse would take place; we hypothesize that more cognitive effort will be necessary to perform these actions for noncanonical sentences.

Data Processing

Pupillometric data were removed if the time window contained greater than 50% missing values; this resulted in the removal of 1.75% of pupillometric data in the no-question condition and of a total of 1.31% of pupillometric data in the question condition. Additionally, entire trials (e.g., baseline and postsentence time windows) were removed if it was judged that a participant was not attending to the task. This was most commonly a result of the participant talking, coughing, or making some other vocalization during the trial. In the no-question condition, of the 10 trials judged as bad and removed, eight were from one participant. A total of 2.38% of trials were removed across all participants in the no-question condition. In the question condition, nine trials were judged as bad and removed, resulting in a total data removal of 1.81%.

Results

Research Question 1

Research Question 1 addressed whether the effect of condition (no-question, question) changed the participants' overall level of arousal, alertness, or task engagement, as reflected in the comparative analyses of tonic pupil responses for each condition. Tonic pupil values were averaged across each participant for each task. Paired-samples t tests indicated no significant difference in average tonic values between question and no-question conditions. There is evidence that the variability rather than the magnitude of tonic and task-evoked responses may be an important indicator of task engagement (Unsworth & Robison, 2017). Standard deviations for both tonic values and mean TERPs were calculated for each participant in each condition. Again, paired-samples t tests indicate that there was no difference between conditions. See Table 2 for descriptive statistics and results.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and t-test results for tonic values, variability in tonic values, and task-evoked responses of the pupil (TERPs) between conditions.

| Measure | Condition | n | M | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tonic pupil diameter | Question | 40 | 3.17 | 0.07 | 1.23 | .23 |

| No-question | 40 | 3.19 | 0.07 | |||

| Variability in tonic pupil diameter | Question | 40 | 0.22 | 0.01 | −1.07 | .29 |

| No-question | 40 | 0.21 | 0.01 | |||

| Variability in mean TERPs | Question | 40 | 0.22 | 0.01 | −1.61 | .12 |

| No-question | 40 | 0.20 | 0.01 |

Research Question 2

Research Question 2 addressed whether the effect of condition (no-question, question) and canonicity (canonical, noncanonical) changed the participants' indices of cognitive effort. To examine the influence of condition and canonicity on cognitive effort as indexed by mean TERPs, we conducted a 2 × 2 analysis of variance. Condition (no-question, question) was the between-participants variable, and canonicity (canonical, noncanonical) was the within-participant variable. We combined mean TERPs from specific sentence types into two groups—canonical and noncanonical—due to the small number of exemplars for individual sentence types.

Dependent variables were tested for normal distribution using the Shapiro–Wilk test, which was chosen due to the limited number of sentence exemplars. All variables were normally distributed with the exception of mean TERPs for noncanonical sentences in the question condition, W(40) = .88, p = .00. When three identified outliers (values greater than 1.5 × IQR) were removed, this variable was normally distributed, W(37) = .98, p = .80. Analyses were completed with and without outliers, and results remained unchanged. Thus, reported results below contain all values. See Table 3 for descriptive statistics.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics: mean task-evoked responses of the pupil in the postsentence time window by canonicity.

| Condition | Sentence type | n | M | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No-question | Canonical | 37 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| Noncanonical | 37 | 0.06 | 0.01 | |

| Question | Canonical | 40 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Noncanonical | 40 | 0.11 | 0.02 |

Note. n = the number of cases included in analyses (cases removed listwise).

The main effect of canonicity and the Canonicity × Condition interaction was significant. The main effect of condition did not reach significance. See Table 4 for results.

Table 4.

Summary of analysis-of-variance results: mean task-evoked responses of the pupil by experimental condition and canonicity.

| Source | df | MS | F | p | ƞ | 1 − β |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | 1, 75 | .02 | 1.62 | .21 | .02 | .24 |

| Canonicity | 1, 75 | .05 | 14.45 | .00 | .16 | .96 |

| Canonicity × Condition | 1, 75 | .03 | 8.34 | .01 | .10 | .81 |

Note. “1 – β” stands for statistical power. MS = mean square.

To explore the Canonicity × Condition interaction, we conducted paired-samples t tests for each condition separately. In the no-question condition, there was no significant difference between mean TERPs for noncanonical (M = 0.06, SE = 0.01) versus canonical (M = 0.06, SE = 0.01) sentences, t(36) = −0.71, p = .48. In the question condition, mean TERPs for noncanonical sentences (M = 0.11, SE = 0.02) were significantly larger than those for canonical sentences (M = 0.05, SE = 0.01), t(39) = −4.42, p = .00.

Discussion

It is important that pupillometric tasks ensure the participants focus their attention on critical aspects of the stimuli under study while minimizing task components that may elicit confounding pupillometric responses. The purpose of this study was to determine whether the anticipation of comprehension questions influenced task engagement (indexed via tonic pupillary responses) and cognitive effort (indexed via TERPs) in a syntactic processing task in individuals without aphasia. Pupil diameter was monitored as participants processed canonical (syntactically easy) and noncanonical (syntactically difficult) sentences in two experimental conditions: one in which they were simply required to listen to the sentences (no-question condition) and one in which they were required to answer yes/no comprehension questions that occurred randomly following 20% of sentences (question condition). Our results are intended to offer an evidence base for future experimental design and to enable a clearer interpretation of results of future pupillometric studies involving PWA.

Research Question 1

Research Question 1 addressed the influence of condition (no-question, question) on the participants' overall level of arousal or task engagement, as indicated by tonic pupillary responses. As hypothesized, there was no difference in the average tonic pupil diameters of participants between the question versus no-question conditions. Tonic pupil measurements have been used as indices of on-task thinking and overall level of arousal. Large tonic pupil measurements are indicators of external information not being processed correctly (Konishi et al., 2017), decreased task utility (Gilzenrat et al., 2010), and decreased attention toward a task (Smallwood et al., 2012). Small tonic pupil measurements have been interpreted as indicators of increased off-topic thoughts (Konishi et al., 2017), as has increased variability in baseline measures (Unsworth & Robison, 2016). In this study, there was no significant difference in either the magnitude or the variability of tonic pupil measures between the no-question and question conditions. This suggests that overall levels of arousal, alertness, and attention toward the task were similar between the conditions.

Research Question 2

Research Question 2 addressed whether condition (no-question, question) and canonicity (canonical, noncanonical) changed the participants' cognitive effort in syntactic processing. We hypothesized that canonicity would influence cognitive effort (e.g., larger TERPs for noncanonical sentences) in both conditions but that the magnitude of the influence may differ between the two. Our hypotheses were partially supported.

No-Question Condition

During the no-question condition, there was no significant effect of canonicity (e.g., pupillometric syntactic difficulty effect); that is, there were no differences in TERPs elicited by noncanonical (difficult) versus canonical (easy) sentences. We hypothesized that this condition might reduce the magnitude of the syntactic difficulty effect; however, it completely eliminated it. It is possible that, without comprehension questions holding participants accountable for attending to the comprehension task, they simply did not pay attention to the stimuli. Two pieces of evidence suggest this interpretation is unlikely. First, there were no differences in tonic pupillary responses between the conditions, as discussed above, indicating similar levels of general attentiveness between the two conditions. Second, pupil responses are only synchronized with stimuli when participants are attending to the task (Kang et al., 2014). In the no-question condition, positive TERPs were elicited by the stimuli, although there was no difference in TERPs elicited by easy and difficult sentences. Positive TERPs indicate that pupils were dilated in the postsentence time window, compared to pupil dilation prior to the onset of the sentence (e.g., baseline pupil diameter). Therefore, pupillary responses were synchronized with stimuli. Together, these results indicate that participants were paying attention to the stimuli in both conditions. A lack of an effect of canonicity in the no-question condition was not due, at least entirely, to off-task thinking, mind-wandering, or misdirected attention.

It may be that the participants were engaged in good-enough processing during the no-question condition (Ferreira et al., 2002; Ferreira & Patson, 2007). While they attended to the stimuli (indexed by positive TERPs), there was no differential level of effort associated with canonicity. Without comprehension questions or another overt behavioral task, participants were not held accountable for forming complete syntactic representations. This may have led to shallow parsing of the sentences. According to the online cognitive equilibrium hypothesis (Karimi & Ferreira, 2016), a shallow initial parse of a sentence will not be overturned unless there is a compelling reason to do so. The participants may have been simply listening to sentences, with no reason to critically examine their interpretations.

Question Condition

In contrast, the influence of canonicity on TERPs was significant in the question condition, suggesting that the anticipation of a comprehension question led participants to allocate effort differentially based on syntactic complexity: Noncanonical sentences elicited greater TERPs (e.g., more effort) than canonical ones. It is important to recall that pupillometric analysis in the no-question condition did not include pupillary data from question trials in which participants heard a question and produced a response. Therefore, it was the anticipation, or expectation, of the question that induced increased cognitive effort for syntactically difficult, noncanonical sentences rather than the overt performance of a response. Canonicity was the only linguistic aspect that differed between canonical and noncanonical sentences, and questions were designed to probe the agent of the sentence. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the anticipation of comprehension questions induced an enhanced focus onto syntactic processing. Regardless of the posited underlying mechanism, noncanonical sentences require more cognitive resources to process. In pupillometric studies, this leads to a syntactic difficulty effect: greater TERPs for noncanonical sentences compared to canonical sentences. We obtained these results only when participants were held accountable for indicating accurate comprehension.

It appears, therefore, that comprehension questions may be necessary to elicit a pupillometric syntactic difficulty effect. However, the anticipation of a question was sufficient to induce the effect. That is, an overt behavioral response (e.g., answering a comprehension question) was not necessary; pupillometric syntactic difficulty effects were present in trials in which a question was not asked. A similar finding has been evidenced in previous pupillometric studies. Brown et al. (1999) had participants complete two versions of the Stroop color-naming task. In one version, participants were asked to name the colors out loud; in the other, they were asked to name them covertly (e.g., silently, to themselves). Pupillometric responses were the same for both tasks: Incongruous stimuli elicited greater TERPs than incongruous stimuli. Einhäuser et al. (2010) observed a time-locking of the pupillometric response with decisions in a digit selection task, even in the conditions in which the overt behavioral response came after the cognitive response of choosing the digit.

Clinical Implications

Pupillometric measures of cognitive effort may be an invaluable resource in terms of identifying inter- and intraindividual cognitive differences that characterize PWA. The presence of occasional question trials appeared to elicit deeper syntactic processing in people without aphasia, as reflected in larger TERPs for more difficult sentences. The finding that the anticipation of a comprehension question is sufficient to induce changes in cognitive effort associated with syntactic processing difficulty is auspicious when considering the potential for studies of cognitive effort in sentence processing in PWA. The finding that participants need not be posed a question following each and every sentence, along with the finding that they need not overtly indicate their answer, reduces the potential confounding effect of an overt motor act on pupillometric responses in individuals who may have concomitant motor impairments. The same effect cannot be assumed for PWA; therefore, we plan to replicate the current study within a population of PWA.

Limitations and Future Directions

A relatively small number of exemplars represented each sentence type, due to the need for control of myriad psycholinguistic factors and the necessity of splitting the set of sentences into two conditions. This precluded a robust analysis of sentence-specific results. Relatedly, we intentionally combined a variety of sentence types into canonical and noncanonical grouped variables, which might be considered a limitation. This was done to increase the generalizability of results to canonicity in general, rather than any specific sentence type, and to develop a sentence bank with which to explore the sensitivity of specific sentence types in future studies with PWA. Exploratory analyses were conducted on TERPs elicited by individual sentence pairs. Results must be interpreted with extreme caution, as there were only five exemplars of each sentence type per condition. Still, the pattern of results was generally consistent: Noncanonical sentences elicited greater TERPs than canonical ones. Unsurprisingly, pairwise comparisons indicated a linear increase in TERPs with sentence length. This is in line with robust work indicating that the amount of cognitive material to be processed at one time will increase cognitive effort as reflected by TERPs (Kahneman & Beatty, 1966; Unsworth & Robison, 2015; Wahn et al., 2016). At the same time, results indicate that even the shortest sentences (unergative/unaccusative) have the potential to elicit a syntactic difficulty effect. Syntax and sentence length may, therefore, have independent influences on effort. This is a topic worthy of future study.

An additional potential limitation is our choice to focus on pupillometric data in the postsentence period; it is possible that the syntactic difficulty effect occurred in other time windows. We did examine other time windows during the exploratory analysis of our data. Specifically, we examined a whole-trial time window (e.g., calculating mean TERP using all pupil data points from the onset of the sentence to the offset of the trial), a verb-oriented time window (e.g., calculating mean TERP using pupil data points from the onset of the verb plus 1,500 ms), and a sentence time window (e.g., calculating mean TERP using all pupil data points from the onset to the offset of the sentence). Analyses in the whole-trial and verb-oriented time windows produced the same pattern of results as the postsentence time window, with effects largely driven by the pupillary responses immediately upon the offset of the sentence (e.g., in the postsentence time window). Analyses in the sentence-oriented time window also led to the same general pattern of results, albeit with smaller effect sizes.

Another limitation is that the intentional choice to consistently present the no-question condition prior to the question condition may have resulted in order effects that were unstudied. Additionally, the intentional limitation of the number of question trials—to minimize the potential for overt responses influencing TERPs—restricted comparisons of TERPs and accuracy on a trial-by-trial level. In the future, such analyses may enrich our understanding of group differences in tonic LC-NE activation; this, in turn, would help elucidate a potential relationship between LC-NE activation and the severity and type of aphasia.

Conclusions

The ability to capture the complexities of cognitive processing makes pupillometry a promising tool for enhancing our understanding of the relationship between cognition and language in people with and without cognitive–linguistic impairments. The interpretation of pupillometric responses can be complex. It is important that the experimental tasks be designed to heighten the participants' attention to critical aspects of the stimuli under study while minimizing task components that may elicit confounding pupillometric responses. Pupillometric syntactic difficulty effects appear to be influenced by a combination of experimental manipulations: the stimuli, the direction of attention toward certain aspects of the stimuli, and the expectation of comprehension questions. All three aspects are important to consider, independently and in combination.

Results from the current study suggest that, in the context of pupillometric studies of syntactic processing, balance may be achieved by asking occasional comprehension questions. When no questions were asked, the participants attended to the task (indicated by results of tonic pupillary responses) but did not appear to engage actively in syntactic processing. Asking intermittent questions held participants accountable for indicating accurate comprehension, enhancing their focus of attention to syntactic processing. Importantly, potential confounding influences of extraneous cognitive and motor tasks on cognitive effort were reduced by not having participants answer a question following every sentence and not including data from question trials in pupillometric analyses. These results will enable an improved experimental design and a clearer interpretation of pupillometric responses when examining cognitive effort involved in syntactic processing in people with and without aphasia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by an Ohio University PhD Fellowship, a College of Health Sciences and Professions Graduate Student Research Grant, and an Ohio University Student Enhancement Award, awarded to Laura Roche Chapman, as well as by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant R43DC010079, a grant from the Virginia Commonwealth Research Commercialization Fund, and a grant from Epstein Teicher Philanthropies, awarded to Brooke Hallowell.

Heartfelt thanks are extended to the following for their invaluable support during various stages of this project: all of our participants, Dixon Cleveland, Pete Norloff, Kenneth Dobo, Anne Fischer, An Dinh, Mohammad Haghighi, Yu Zhang, Perri Waisner, Chao-Yang Lee, Francois Brajot, James Montgomery, and Anne Fischer.

Funding Statement

This study was supported in part by an Ohio University PhD Fellowship, a College of Health Sciences and Professions Graduate Student Research Grant, and an Ohio University Student Enhancement Award, awarded to Laura Roche Chapman, as well as by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant R43DC010079, a grant from the Virginia Commonwealth Research Commercialization Fund, and a grant from Epstein Teicher Philanthropies, awarded to Brooke Hallowell.

References

- Alnæs, D. , Sneve, M. H. , Espeseth, T. , Endestad, T. , van de Pavert, S. H. , & Laeng, B. (2014). Pupil size signals mental effort deployed during multiple object tracking and predicts brain activity in the dorsal attention network and the locus coeruleus. Journal of Vision, 14(4), 1. https://doi.org/10.1167/14.4.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayasse, N. D. , & Wingfield, A. (2018). A tipping point in listening effort: Effects of linguistic complexity and age-related hearing loss on sentence comprehension. Trends in Hearing, 22, 2331216518790907. https://doi.org/10.1177/2331216518790907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahlmann, J. , Rodriguez-Fornells, A. , Rotte, M. , & Munte, T. F. (2007). An fMRI study of canonical and noncanonical word order in German. Human Brain Mapping, 28(10), 940–949.n. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastiaanse, R. , Edwards, S. , & Rispens, J. (2002). Verb and Sentence Test (VAST). Thames Valley Test Company. [Google Scholar]

- Beatty, J. , & Lucero-Wagoner, B. (2000). The pupillary system. In Cacioppo J. T., Tassinary L. G., & Berntson G. G. (Eds.), Handbook of psychophysiology (2nd ed., pp. 142–162). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Nun, Y. (1986). The use of pupillometry in the study of on-line verbal processing: Evidence for depths of processing. Brain and Language, 28(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/0093-934X(86)90086-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird, H. , Franklin, S. , & Howard, D. (2001). Age of acquisition and imageability ratings for a large set of words, including verbs and function words. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 33(1), 73–79. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03195349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G. G. , Kindermann, S. S. , Siegle, G. J. , Granholm, E. , Wong, E. C. , & Buxton, R. B. (1999). Brain activation and pupil response during covert performance of the Stroop Color Word task. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 5(4), 308–319. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617799544020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brysbaert, M. , & New, B. (2009). Moving beyond Kučera and Francis: A critical evaluation of current word frequency norms and the introduction of a new and improved word frequency measure for American English. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 977–990. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, K. L. , Samu, D. , Davis, S. W. , Geerligs, L. , Mustafa, A. , & Tyler, L. K. (2016). Robust resilience of the frontotemporal syntax system to aging. The Journal of Neuroscience, 36(19), 5214–5227. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4561-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan, D. , DeDe, G. , & Michaud, J. (2006). Task-independent and task-specific syntactic deficits in aphasic comprehension. Aphasiology, 20(9), 893–920. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030600739273 [Google Scholar]

- Caplan, D. , Waters, G. , DeDe, G. , Michaud, J. , & Reddy, A. (2007). A study of syntactic processing in aphasia I: Behavioral (psycholinguistic) aspects. Brain and Language, 101(2), 103–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandl.2006.06.225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, L. R. , & Hallowell, B. (2015). A novel pupillometric method for indexing word difficulty in individuals with and without aphasia. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 58(5), 1508–1520. https://doi.org/10.1044/2015_JSLHR-L-14-0287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, L. R. , & Hallowell, B. (2016, May). Indexing cognitive effort: Effects of linguistic difficulty and stimulus modality [Conference session] . Clinical Aphasiology Conference, Charlottesville, VA, United States. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, L. R. , & Hallowell, B. (2019, June). Real-time tracking of cognitive effort during sentence processing in aphasia: Pupillometric evidence [Conference session] . Clinical Aphasiology Conference, Whitefish, MT, United States. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, D. G. (2011). Sentence comprehension in aphasia. Language and Linguistics Compass, 5(10), 718–730. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-818X.2011.00309.x [Google Scholar]

- Dinh, A. , & Hallowell, B. (2015, November). A comparison of fixation duration and pupillometric measures as indices of cognitive effort during linguistic processing [Poster presentation] . Annual Convention of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Denver, CO, United States. [Google Scholar]

- Einhäuser, W. , Koch, C. , & Carter, O. L. (2010). Pupil dilation betrays the timing of decisions. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 4, 18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2010.00018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, F. , Bailey, K. G. D. , & Ferraro, V. (2002). Good-enough representations in language comprehension. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11(1), 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00158 [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, F. , & Patson, N. D. (2007). The “good enough” approach to language comprehension. Language and Linguistics Compass, 1(1–2), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-818X.2007.00007.x [Google Scholar]

- Foroughi, C. K. , Sibley, C. , & Coyne, J. T. (2017). Pupil size as a measure of within-task learning. Psychophysiology, 54(10), 1436–1443. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.12896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilzenrat, M. S. , Nieuwenhuis, S. , Jepma, M. , & Cohen, J. D. (2010). Pupil diameter tracks changes in control state predicted by the adaptive gain theory of locus coeruleus function. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 10(2), 252–269. https://doi.org/10.3758/CABN.10.2.252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haghighi, M. H. , & Hallowell, B. (2015, November). Pupillometric indices of sentence processing effort: Interaction of information structure and syntactic structure [Poster presentation] . Annual Convention of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Denver, CO, United States. [Google Scholar]

- Haghighi, M. H. , & Hallowell, B. (2017). Real-time tracking of cognitive effort associated with memory limitations during sentence processing [Poster presentation] . Annual Convention of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Los Angeles, CA, United States. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.24826.39363

- Haghighi, M. H. , & Hallowell, B. (2019, June). Cognitive effort allocation during short-term memory retention in post-stroke aphasia [Conference session] . Clinical Aphasiology Conference, Whitefish, MT, United States. [Google Scholar]

- Hallowell, B. (2008). Strategic design of protocols to evaluate vision in research on aphasia and related disorders. Aphasiology, 22(6), 600–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030701429113 [Google Scholar]

- Hallowell, B. , Wertz, R. T. , & Kruse, H. (2002). Using eye movement responses to index auditory comprehension: An adaptation of the Revised Token Test. Aphasiology, 16(4–6), 587–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030244000121 [Google Scholar]

- Hess, E. H. , & Polt, J. M. (1964). Pupil size in relation to mental activity during simple problem-solving. Science, 143(3611), 1190–1192. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.143.3611.1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyönä, J. , Tommola, J. , & Alaja, A.-M. (1995). Pupil dilation as a measure of processing load in simultaneous interpretation and other language tasks. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A: Human Experimental Psychology, 48A(3), 598–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/14640749508401407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyvärinen, L. , Näsänen, R. , & Laurinen, P. (1980). New visual acuity test for pre-school children. Acta Ophthalmologica, 58(4), 507–511. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-3768.1980.tb08291.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova, M. V. , & Hallowell, B. (2012). Validity of an eye-tracking method to index working memory in people with and without aphasia. Aphasiology, 26(3–4), 556–578. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2011.618219 [Google Scholar]

- Just, M. A. , & Carpenter, P. A. (1993). The intensity dimension of thought: Pupillometric indices of sentence processing. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 47(2), 310–339. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0078820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D. (1973). Attention and effort. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D. , & Beatty, J. (1966). Pupil diameter and load on memory. Science, 154(3756), 1583–1585. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.154.3756.1583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang, O. E. , Huffer, K. E. , & Wheatley, T. P. (2014). Pupil dilation dynamics track attention to high-level information. PLOS ONE, 9(8), Article e102463. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0102463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, H. , & Ferreira, F. (2016). Good-enough linguistic representations and online cognitive equilibrium in language processing. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 69(5), 1013–1040. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2015.1053951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E. S. , Suleman, S. , & Hopper, T. (2018). Cognitive effort during a short-term memory (STM) task in individuals with aphasia. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 48, 190–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroling.2017.12.007 [Google Scholar]

- Konishi, M. , Brown, K. , Battaglini, L. , & Smallwood, J. (2017). When attention wanders: Pupillometric signatures of fluctuations in external attention. Cognition, 168, 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2017.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laeng, B. , Waterloo, K. , Johnsen, S. H. , Bakke, S. J. , Låg, T. , Simonsen, S. S. , & Høgsæt, J. (2007). The eyes remember it: Oculography and pupillometry during recollection in three amnesic patients. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 19(11), 1888–1904. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2007.19.11.1888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Technologies LC. (2009). The Eyegaze analysis system—User's manual. Eyegaze, Inc.

- Loewenfeld, I. E. , & Lowenstein, O. (1993). The pupil: Anatomy, physiology, and clinical applications. Wayne State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil, M. R. , Hula, W. D. , & Sung, J. E. (2011). The role of memory and attention in aphasic language performance. In Guendouzi J., Loncke F., & Williams M. J. (Eds.), The handbook of psycholinguistic and cognitive processes: Perspectives in communication disorders (pp. 551–577). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, A. M. , Mack, J. E. , & Thompson, C. K. (2012). Tracking passive sentence comprehension in agrammatic aphasia. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 25(1), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroling.2011.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, J. W. , & Evans, J. L. (2009). Complex sentence comprehension and working memory in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 52(2), 269–288. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2008/07-0116) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moresi, S. , Adam, J. J. , Rijcken, J. , Van Gerven, P. W. M. , Kuipers, H. , & Jolles, J. (2008). Pupil dilation in response preparation. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 67(2), 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2007.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P. R. , O'Connell, R. G. , O'Sullivan, M. , Robertson, I. H. , & Balsters, J. H. (2014). Pupil diameter covaries with BOLD activity in human locus coeruleus. Human Brain Mapping, 35(8), 4140–4154. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.22466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P. R. , Robertson, I. H. , Balsters, J. H. , & O'Connell, R. G. (2011). Pupillometry and P3 index the locus coeruleus–noradrenergic arousal function in humans. Psychophysiology, 48(11), 1532–1543. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01226.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray, L. L. (2012). Attention and other cognitive deficits in aphasia: Presence and relation to language and communication measures. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 21(2), S51–S64. https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2012/11-0067) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray, L. L. (2017). Focusing attention on executive functioning in aphasia. Aphasiology, 31(7), 721–724. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2017.1299854 [Google Scholar]

- Nasreddine, Z. S. , Phillips, N. A. , Bédirian, V. , Charbonneau, S. , Whitehead, V. , Collin, I. , Cummings, J. L. , & Chertkow, H. (2005). The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53(4), 695–699. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norloff, P. , & Cleveland, D. (2017). Pupillometric Program for the Eyetracking Comprehension Assessment System. LC Technologies. [Google Scholar]

- Piquado, T. , Isaacowitz, D. , & Wingfield, A. (2010). Pupillometry as a measure of cognitive effort in younger and older adults. Psychophysiology, 47(3), 560–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00947.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkowski, J. , Majczynski, H. , Clayton, E. , & Aston-Jones, G. (2004). Activation of monkey locus coeruleus neurons varies with difficulty and performance in a target detection task. Journal of Neurophysiology, 92(1), 361–371. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00673.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhard, G. , Lachnit, H. , & König, S. (2007). Effects of stimulus probability on pupillary dilation and reaction time in categorization. Psychophysiology, 44(3), 469–475. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00512.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richer, F. , & Beatty, J. (1985). Pupillary dilations in movement preparation and execution. Psychophysiology, 22(2), 204–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1985.tb01587.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richer, F. , Silverman, C. , & Beatty, J. (1983). Response selection and initiation in speeded reactions: A pupillometric analysis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 9(3), 360–370. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-1523.9.3.360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salis, C. , & Edwards, S. (2009). Tests of syntactic comprehension in aphasia: An investigation of task effects. Aphasiology, 23(10), 1215–1230. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030802380165 [Google Scholar]

- Samuels, E. R. , & Szabadi, E. (2008). Functional neuroanatomy of the noradrenergic locus coeruleus: Its roles in the regulation of arousal and autonomic function part II: Physiological and pharmacological manipulations and pathological alterations of locus coeruleus activity in humans. Current Neuropharmacology, 6(3), 254–285. https://doi.org/10.2174/157015908785777193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg, C. W. (2017). Hypoconnectivity of resting-state networks in persons with aphasia compared with healthy age-matched adults. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11, 91. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluroff, M. (1982). Pupil responses to grammatical complexity of sentences. Brain and Language, 17(1), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/0093-934X(82)90010-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- School of Psychology, The University of Western Australia. (2015). MRC Psycholinguistic Database (Dict Utility Interface). http://websites.psychology.uwa.edu.au/school/MRCDatabase/uwa_mrc.htm

- Shtyrov, Y. (2010). Automaticity and attentional control in spoken language processing: Neurophysiological evidence. The Mental Lexicon, 5(2), 255–276. https://doi.org/10.1075/ml.5.2.06sht [Google Scholar]

- Sirois, S. , & Brisson, J. (2014). Pupillometry. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 5(6), 679–692. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smallwood, J. , Brown, K. S. , Baird, B. , Mrazek, M. D. , Franklin, M. S. , & Schooler, J. W. (2012). Insulation for daydreams: A role for tonic norepinephrine in the facilitation of internally guided thought. PLOS ONE, 7(4), Article e33706. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0033706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanners, R. F. , Headley, D. B. , & Clark, W. R. (1972). The pupillary response to sentences: Influences of listening set and deep structure. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11(2), 257–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(72)80086-0 [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauer, S. R. , Siegle, G. J. , Condray, R. , & Pless, M. (2004). Sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation of pupillary dilation during sustained processing. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 52(1), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2003.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, C. K. , & Shapiro, L. P. (2005). Treating agrammatic aphasia within a linguistic framework: Treatment of Underlying Forms. Aphasiology, 19(10–11), 1021–1036. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030544000227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traxler, M. J. , Morris, R. K. , & Seely, R. E. (2002). Processing subject and object relative clauses: Evidence from eye movements. Journal of Memory and Language, 47(1), 69–90. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmla.2001.2836 [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth, N. , & Robison, M. K. (2015). Individual differences in the allocation of attention to items in working memory: Evidence from pupillometry. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 22, 757–765. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-014-0747-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth, N. , & Robison, M. K. (2016). Pupillary correlates of lapses of sustained attention. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 16(4), 601–615. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-016-0417-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth, N. , & Robison, M. K. (2017). The importance of arousal for variation in working memory capacity and attention control: A latent variable pupillometry study. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 43(12), 1962–1987. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0000421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usher, M. , Cohen, J. D. , Servan-Schreiber, D. , Rajkowski, J. , & Aston-Jones, G. (1999). The role of locus coeruleus in the regulation of cognitive performance. Science, 283(5401), 549–554. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.283.5401.549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verney, S. P. , Granholm, E. , & Dionisio, D. P. (2001). Pupillary responses and processing resources on the visual backward masking task. Psychophysiology, 38(1), 76–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-8986.3810076 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villard, S. , & Kiran, S. (2015). Between-session intra-individual variability in sustained, selective, and integrational non-linguistic attention in aphasia. Neuropsychologia, 66, 204–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.11.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villard, S. , & Kiran, S. (2016). To what extent does attention underlie language in aphasia? Aphasiology, 31(10), 1226–1245. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2016.1242711 [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, A. E. , Nagels, L. , Toffanin, P. , Opie, J. M. , & Başkent, D. (2019). Individual variations in effort: Assessing pupillometry for the hearing impaired. Trends in Hearing, 23, 2331216519845596. https://doi.org/10.1177/2331216519845596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahn, B. , Ferris, D. P. , Hairston, W. D. , & König, P. (2016). Pupil sizes scale with attentional load and task experience in a Multiple Object Tracking task. PLOS ONE, 11(12), e0168087. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0168087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, H. H. , & Fergadiotis, G. (2012). Conceptualising and measuring working memory and its relationship to aphasia. Aphasiology, 26(3–4), 258–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2011.604304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, P. , & Kahneman, D. (1971). Evidence for alternative strategies of sentence retention. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 23(2), 197–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/14640747108400240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.