Abstract

Background:

The effectiveness of implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) on reducing mortality has not been well studied in patients with long QT syndrome (LQTS).

Objectives:

We aimed to assess the survival benefits of ICDs in the overall LQTS population and in subgroups defined by ICD indications.

Methods:

We included 3,035 patients (597 with ICD) from the Rochester LQTS Registry with a QTc ≥470 ms or confirmed LQTS mutation. Using multivariable Cox proportional hazards models, we estimated the risk of all-cause mortality, all-cause mortality before age 50 years, and sudden cardiac death (SCD) as a function of time-dependent ICD therapy. Indication subgroups examined included: 1) patients with non-fatal cardiac arrest; 2) with syncope while on beta-blockers; and 3) with a QTc ≥ 500ms and syncope while off beta-blockers.

Results:

During 118,837 person-years follow-up, 389 patients died (137 before age 50; 116 experienced SCD). In the entire population, ICD patients had a lower risk of death (HR=0.54, 95%CI: 0.34 – 0.86), death before age 50 (HR=0.29 [0.14 – 0.61]), and SCD (HR=0.22 [0.09 – 0.55]) than non-ICD patients. ICD patients also had a lower risk of mortality among the three indication subgroups (HR=0.14 [0.06 – 0.34], 0.27 [0.10 – 0.72], and 0.42 [0.19 – 0.96], respectively).

Conclusions:

ICD therapy was associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality, all-cause mortality before age 50, and SCD in the LQTS population, and a lower risk of all-cause mortality in indication subgroups. This study provides evidence supporting ICD implantation in high-risk LQTS patients.

Keywords: long QT syndrome, implantable cardioverter defibrillator, sudden cardiac death, mortality, genotype, mutation

Condensed abstract:

Survival benefit of ICD therapy for LQTS patients remains unclear. Based on data from the Rochester LQTS Registry, time-varying ICD was associated with lower risk of death, death before age 50, and SCD in LQTS patients, and lower risk of post-indication death in the following indication subgroups: 1) nonfatal cardiac arrest; 2) syncope while on beta-blockers; and 3) syncope while off beta-blockers and a QTc ≥ 500ms. This study provides evidence for guideline recommendations of ICDs in patients with the first two indications. Further, it suggests that the third group may also benefit from ICD therapy.

Congenital long QT syndrome (LQTS) is a genetic channelopathy that predisposes patients to ventricular tachyarrhythmias and sudden cardiac death (SCD) (1). It is a leading cause of SCD in young subjects without a structural heart disease (2). Implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD) were first used in heart failure patients with left ventricular dysfunction to prevent SCD, with their survival benefit established by several clinical trials (3–4), Since then, ICD therapy has also been used in LQTS patients (5–6). However, its effect on reducing SCD and all-cause mortality has not been well studied in the LQTS population.

In the present study, we evaluated the effectiveness of ICD therapy for reducing the risk of all-cause mortality, all-cause mortality before age 50 years, and SCD in LQTS patients using data from the Rochester LQTS Registry. Furthermore, we also examined the effectiveness of ICD therapy for reducing all-cause mortality in each of the two indication subgroups as defined by current practice guidelines (7–8): 1) patients with nonfatal cardiac arrest (NFCA, Class I indication), 2) patients with syncope occurring while on beta-blockers (Class IIa indication). A third subgroup, patients with significant QTc prolongation (i.e., ≥ 500 ms) and syncope while off beta-blockers, was also examined. For this group, ICD implantation lacks clear recommendations, and many patients and physicians asked the question whether with such QTc prolongation it is necessary to implant an ICD.

METHODS

Study population

The study population included LQTS patients in the Rochester LQTS Registry, which is the US portion of the International LQTS Registry established in 1979 (9). The registry includes both retrospective (i.e., before enrollment) and prospective (i.e., after enrollment) follow-up and data collection. Participants in the Registry are LQTS patients and their family members enrolled across the United States. Patients included in the present study were enrolled before December 21, 2016. To evaluate the effectiveness of ICDs, we included participants with a QTc ≥ 470ms or those who were genotype positive. Patients whose follow-up time from birth was less than 1 year (including those who died prior to 1 year of age) or had missing QTc were excluded, resulting in 3,035 patients in the final analyses. Among the 3,035 patients, 597 had a history of ICD implantation. To estimate the risk of inappropriate ICD shocks and ICD complications, we included 282 of the 597 ICD patients who also were enrolled in the parallel LQTS-ICD registry. The LQTS-ICD registry was established in 2000 and included LQTS patients with an implanted ICD. All participants provided written informed consent, and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Rochester Medical Center.

Registry data collection and follow-up

At enrollment to the Rochester LQTS registry, a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) was obtained for all patients included in this study and read centrally by the study physicians at the University of Rochester Medical Center. QTc was calculated using Bazett’s formula. For probands, QTc was measured from the first ECG received and read by the reading center showing a qualifying QTc of >440ms. For family members, QTc was measured from the earliest ECG available. Genetic testing results reported by laboratories or patients’ physicians were also documented. At enrollment, each patient completed a questionnaire that collected data on demographic information, contact information of the patient’s physician, medical history including cardiac events (pre-syncope, syncope, and NFCA), family history of LQTS and SCD, medication use, other LQTS-related therapy including ICD therapy, and comorbidities. Patients were followed annually using mailed questionnaires to obtain updates on the above information. When an arrhythmic event or surgical procedure (e.g., ICD implantation) was reported by the patient, the patient’s physician was contacted to verify the information. For probands, annual follow-up with patients’ physicians was routinely performed. Since 2001, the registry has conducted separate annual surveys for cardiovascular comorbidities for participants who reached their 40s and consented to participate. This annual survey collected detailed comorbidity information including coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes, hypertension, and subjective heart failure symptoms. A detailed definition of each comorbidity examined in the study was included in supplemental materials.

A patient was considered as “on ICD therapy” if the patient had an ICD implanted and the device was active. Appropriate ICD shocks were defined as shocks delivered for ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation. The type of arrhythmia that triggered a shock and the appropriateness of the shock were adjudicated by an event committee, based on all information available including reports from the patient’s electrophysiologist and device interrogations.

The primary endpoint for the study was all-cause mortality. Secondary endpoints included all-cause mortality before age 50 (to minimize the effect of comorbidities contributing to mortality at older age) and SCD. Mortality was assessed by contact with relatives of the deceased and available medical documentation. SCD was defined as death abrupt in onset without evident cause if witnessed or death that was not explained by any other cause if it occurred in a non-witnessed setting such as sleep (1,5). SCDs were adjudicated by LQTS investigators based on a description of the circumstances around the time of death and medical records when available.

ICD-related complications were only available for ICD patients who were enrolled in the LQTS-ICD registry (n=282). The registry performed bi-annual follow-up for physicians and annual follow-up for patients. Only ICD complications that required lead-related or generator-related surgical procedures were collected. Complications examined by the present study included lead fracture/dislodgment, ICD-related infections, and generator malfunction.

Statistical analysis

ICD and mortality endpoints: all patients

Comparisons of clinical characteristics between patients ever vs. never received an ICD were performed using Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables and Chi-square test for categorical variables. We used time-dependent Cox models to estimate the risk of all-cause mortality associated with ICD therapy. Person-time at risk was calculated from age 1 year until death or last registry contact (i.e., time-dependent age [minus 1] was used as the timescale and thus was nonparametrically controlled). ICD therapy was analyzed as a time-dependent variable, allowing its value to change between 0 (off ICD) and 1 (on ICD) over time. The model was stratified by sex, decade of birth (selection of cut-offs was described in supplements), and genotype (seven strata as shown in Table 1), and further parametrically adjusted for QTc and time-dependent covariates including beta-blocker use, evolving history of cardiac events (a composite event of NFCA, syncope, or appropriate ICD shocks occurring while on or off beta-blockers; see supplements for details), family history of SCD/NFCA, and comorbidities including coronary heart disease, heart failure, cancer, diabetes, hypertension, and stroke. Two sensitivity analyses were performed: 1) additionally adjust for time-dependent sodium channel blockers, pacemakers, and left cardiac sympathetic denervation; 2) use enrollment as the time origin and time on study as the time scale in Cox models.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Long QT Syndrome Patients with and without an ICD.

| Overall | Non-ICD | ICD* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-value | ||||

| Clinical Characteristics | (N=3,035) | (N=2,438) | (N=597) | |

| Male | 1,213 (40.0) | 1,028 (42.2) | 185 (31.0) | <.001 |

| Age at enrollment† | 24 (11 – 44) | 24 (10 – 45) | 24 (14 – 38) | 0.949 |

| Mean QTc, ms | 480 (460 – 510) | 480 (460 – 500) | 500 (470 – 540) | <.001 |

| QTc ms | <.001 | |||

| <470 (genotype positive) | 793 (26.1) | 687 (28.2) | 106 (17.8) | |

| 470 – <500 | 1,143 (37.7) | 954 (39.1) | 189 (31.7) | |

| 500 – <550 | 726 (23.9) | 551 (22.6) | 175 (29.3) | |

| ≥550 | 373 (12.3) | 246 (10.1) | 127 (21.3) | |

| Genotype | <.001§ | |||

| Total genotyped | 1813 (59.7) | 1398 (57.3) | 415 (69.5) | |

| LQT1 (single mutation)‡ | 752 (41.5) | 645 (46.1) | 107 (25.8) | |

| LQT2 (single mutation)‡ | 724 (39.9) | 527 (37.7) | 197 (47.5) | |

| LQT3 (single mutation)‡ | 211 (11.6) | 133 (9.5) | 78 (18.8) | |

| Others (single mutation)‡ | 49 (2.7) | 34 (2.4) | 15 (3.6) | |

| Multiple mutations‡ | 77 (4.2) | 59 (4.2) | 18 (4.3) | |

| Negative for mutation tested | 192 (6.3) | 170 (7.0) | 22 (3.7) | |

| Not tested/Unknown | 1030 (33.9) | 870 (35.7) | 160 (26.8) | |

| Before ICD implantation ¶ | ||||

| Cardiac events | <.001 | |||

| No event | 1,713 (56.4) | 1,580 (64.8) | 133 (22.3) | |

| Syncope while off beta-blockers | 752 (24.8) | 561 (23.0) | 191 (32.0) | |

| Syncope while on beta-blockers | 342 (11.3) | 199 (8.2) | 143 (24.0) | |

| Non-fatal cardiac arrest | 228 (7.5) | 98 (4.0) | 130 (21.8) | |

| Pacemaker | 243 (8.0) | 129 (5.3) | 114 (19.1) | <.001 |

| At any time during follow-up | ||||

| Beta-blockers | 2051 (67.6) | 1494 (61.3) | 557 (93.3) | <.001 |

| Sodium channel blockers | 128 (4.2) | 59 (2.4) | 69 (11.6) | <.001 |

| Left cardiac sympathetic denervation | 53 (1.7) | 32 (1.3) | 21 (3.5) | <.001 |

Data are mean ± SD or N (%). P values are for comparisons between ICD and non-ICD patients. P values only serve as additional descriptive statistics and should be interpreted with caution, since the two groups were defined based on ICD status evolution over entire follow-up (i.e., looking ahead of time).

Person-years on ICD was 5,486, which was 4.6 % of the total follow-up time (118,837 person-years) of the study population.

For those who died before enrollment, age at enrollment was the same as age at death.

Percentages were computed using the total number of genotyped patients as denominators.

P value compared the genotype distribution between the ICD and non-ICD group among genotyped patients only.

For the non-ICD group, data shown are cardiac events and pacemaker implantation at any time during follow-up (ever vs. never). NFCA, syncope on beta-blockers, and syncope off beta-blockers were mutually exclusive groups. If a patient experienced multiple cardiac events prior to ICD implantation, he/she was classified in the group with the highest presumed risk (NFCA>syncope on beta-blockers >syncope off beta-blockers).

The risks of the two secondary endpoints associated with time-dependent ICD therapy were estimated in a similar way. For all-cause mortality before age 50, follow-up started from age 1 and was censored at the last registry contact or the date of a subject’s 50th birthday, whichever occurred first. For SCD, follow-up started from age 1 and was censored at the last registry contact or date of death due to reasons other than SCD, whichever occurred first. For these two secondary endpoints, comorbidities were not included in the Cox models.

ICD and mortality endpoints: indication subgroups

To estimate the risk of all-cause mortality (primary endpoint) associated with ICD therapy by indication subgroups, we identified three groups of patients based on history of indication events: 1) patients with a history of NFCA prior to ICD implant, 2) patients with a history of syncope while on beta-blockers prior to ICD implant, and 3) patients with a history of syncope while off beta-blockers prior to ICD implant and with a QTc ≥ 500 ms. If a patient experienced multiple indication events, the patient could be included in multiple indication subgroups depending on the temporality of these events. If the patient experienced a higher-risk event (presumed risk: NFCA>syncope on beta-blockers>syncope off beta-blockers) first and a lower-risk event later, then he/she was only included in the higher risk indication subgroup. If the patient experienced a lower-risk event first and a higher-risk event later, then he/she was included in both indication subgroups.

A Cox model including time-dependent ICD therapy was fit separately for each of the three indication subgroups. In each subgroup, follow-up started from the time of the indication event and was censored at the last registry contact. Given that patients in the same indication subgroup all experienced the same cardiac event when follow-up started (i.e. the most important confounder has been controlled), and given the limited number of events in these subgroup analyses, the models were adjusted only for age, calendar year of the indication event, and comorbidities, and stratified by sex. In sensitivity analyses, we censored follow-up at the time when a subject developed a higher-risk cardiac event (i.e., censoring follow-up at the time when a subject developed NFCA for the indication subgroup of syncope on beta-blockers; censoring follow-up at the time when a subject developed syncope on beta-blockers or NFCA for the indication subgroup of syncope off beta-blockers and a QTc ≥ 500 ms).

For all analyses using Cox models, robust sandwich estimates of standard errors were used to account for potential dependence due to family membership. Proportional hazards assumptions were tested via interactions of each covariate with log(time), and models were extended to include these interactions if statistically significant (e.g., evolving history of cardiac events). There was insufficient evidence of non-proportional hazards for time-dependent ICD therapy in all models.

Risk of inappropriate ICD shocks and ICD complications

The risks of inappropriate ICD shocks and major ICD complications (lead dysfunction, ICD-related infections, and generator dysfunction) were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier estimator, with follow-up starting from the date of the first ICD implantation. Separately, the rates of inappropriate ICD shocks and each type of ICD complications were calculated as the number of events (recurrent events were also counted) per 100 person-years on ICD. All analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS institute Inc., Cary, NC) with p<0.05 used to define statistical significance.

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of ICD patients and non-ICD patients

During a median follow-up of 36.3 years since age 1 (range: 0.02 [1 week] – 106 years; total person-years: 118,837), 597 patients received an ICD (person-years on ICD: 5,486). The median age at ICD implantation was 28 years (interquartile range: 17 – 43 years). Only 29 patients ever had ICD explanted or deactivated after initial implantation. Clinical characteristics of all patients and by patients who ever received an ICD (ICD group) versus patients who never received an ICD (non-ICD group) during follow-up is shown in Table 1. The majority of genotyped patients had a single mutation on LQT1, LQT2, or LQT3 (93.1% of all genotyped patients, 55.7% of all patients). The ICD group generally had a higher LQTS risk profile than the non-ICD group, as reflected by a longer median QTc (500 ms vs. 480 ms), a higher proportion of females (69.0% vs. 57.8%), and a higher proportion of patients with NFCA or syncope during ICD treatment naïve time (77.7% vs. 35.2%). The ICD group also had a higher proportion of patients who ever developed coronary artery disease (6.9% vs. 3.6%), congestive heart failure (5.2% vs.2.6%), or stroke (2.8% vs 1.6%) during follow-up (Supplemental Table S1).

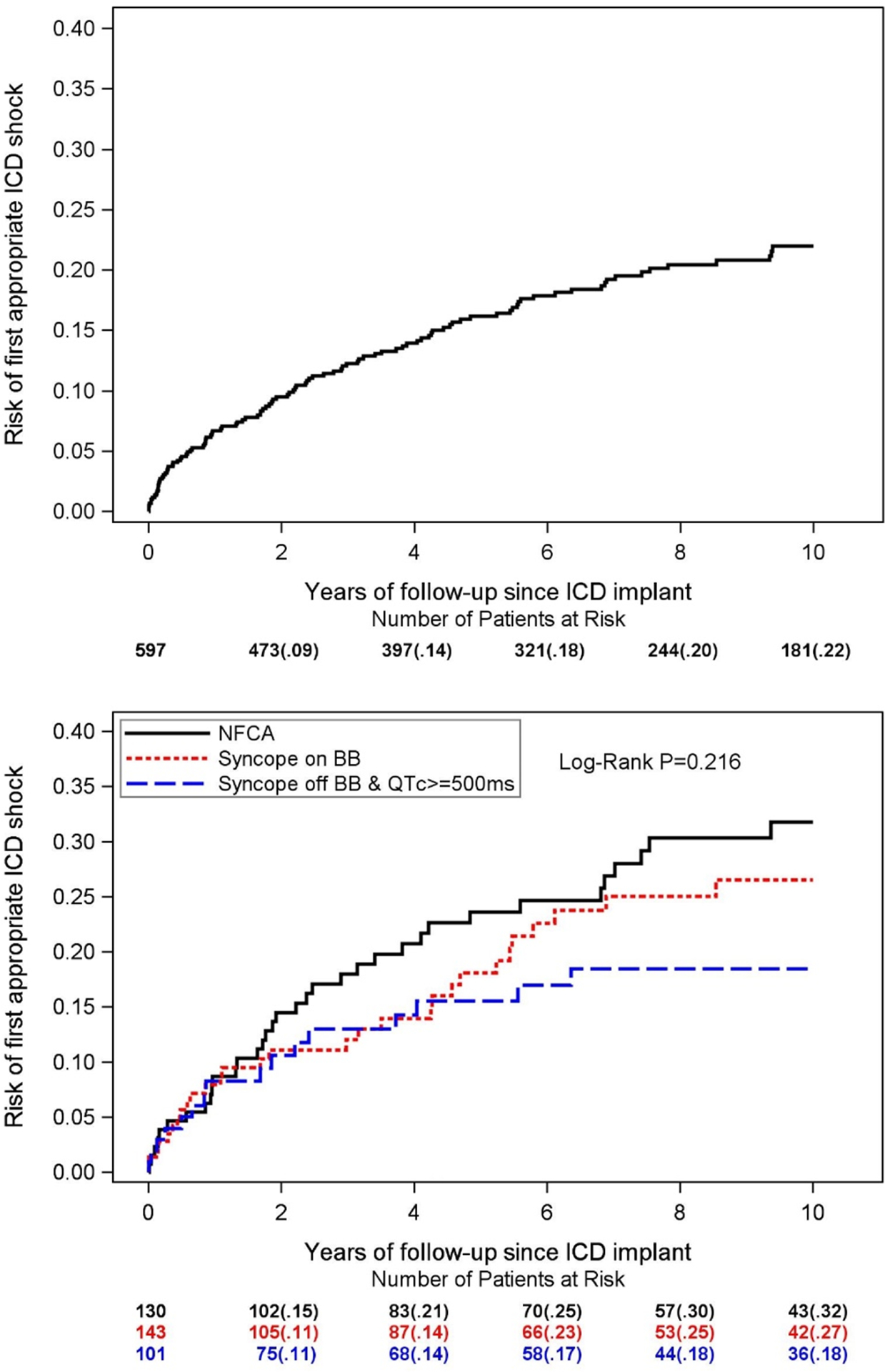

Of the 597 patients in the ICD group, 115 experienced at least one appropriate ICD shock, and 86 experienced the shock while on beta-blockers. The 10-year risk of first life-threatening arrhythmia as assessed by the Kaplan-Meier estimator of appropriate ICD shocks was 22% (Figure 1, top panel). There were 374 ICD patients experienced at least one indication event prior to ICD implantation, and there were no significant differences in the distribution of Kaplan-Meier curves of appropriate ICD shocks between the three indication subgroups defined at the time of ICD implantation (Figure 1, bottom panel).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier curve for the risk of first appropriate ICD shock.

Top panel: among all 597 ICD patients; Bottom panel: by indication event (NFCA, syncope while on beta blockers, and syncope while off beta blockers with a QTc ≥ 500ms) at the time of ICD implantation. As suggested by the log-rank p value, there were no statistically significant differences in the distribution of curves between the three indication subgroups. ICD: implantable cardioverter defibrillator; NFCA: non-fatal cardiac arrest; BB: beta blockers.

Risk of mortality endpoints associated with time-dependent ICD therapy

During a follow-up of 118,837 person-years from age one, 389 patients died (23 died while on ICD). Of the 389 patients, 137 died prior to age 50 years, and 116 experienced SCD. The crude rates of all-cause mortality, all-cause mortality prior to age 50 years, and SCD were 0.33, 0.14, and 0.10 per 100 person-years, respectively. Cause of death for the 23 patients who died while on ICD is shown in Supplemental Table S2.

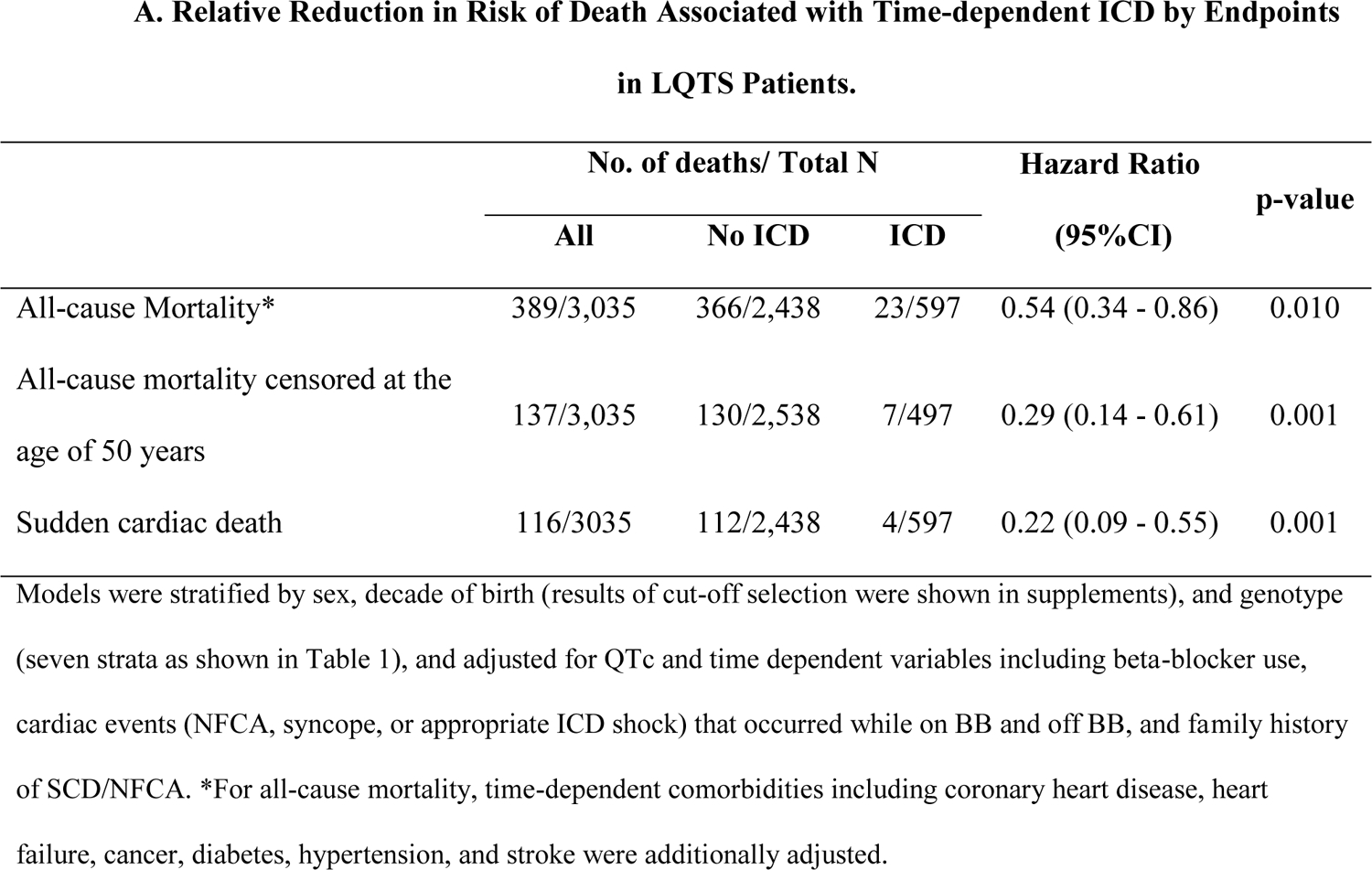

Among the entire population, patients with an ICD had a 46% lower risk of death (HR=0.54, 95% CI: 0.34 – 0.86, p=0.010), a 71% lower risk of death before age 50 (HR=0.29, 95% CI: 0.14 – 0.61, p=0.001), and a 78% lower risk of SCD (HR=0.22, 95% CI: 0.09 – 0.55, p=0.001) compared to patients without an ICD after age 1 (Central Illustration, part A), accounting for sex, decade of birth, genotype, QTc, beta-blocker use, cardiac events, family history of SCD/NFCA, and comorbidities (for the all-cause mortality endpoint only). Further adjustment for time-dependent sodium channel blocker, pacemaker, and left cardiac sympathetic denervation gave essentially the same results (HR=0.54 [95% CI: 0.34 – 0.87] for all-cause mortality; HR=0.28 [95% CI: 0.13 – 0.60] for all-cause mortality before age 50; HR=0.21 [95% CI: 0.08–0.52] for SCD). Results were not substantially changed when using enrollment as the time origin (Supplemental Table S3)

Central Illustration. Reduction in Mortality with ICD in LQTS Patients.

A. Relative Reduction in Risk of Death Associated with Time-dependent ICD by Endpoints in LQTS Patients. B. Relative reduction in post-indication all-cause mortality associated with time-dependent ICD. Indication subgroups examined included 1) patients with a history of NFCA, 2) patients with syncope occurring while on BB, and 3) patients with syncope occurring while off BB with a QTc ≥ 500ms. In all three subgroups, ICD was significantly associated with a lower risk of post-indication all-cause mortality. ICD: implantable cardioverter defibrillator; NFCA: non-fatal cardiac arrest; BB: beta-blockers.

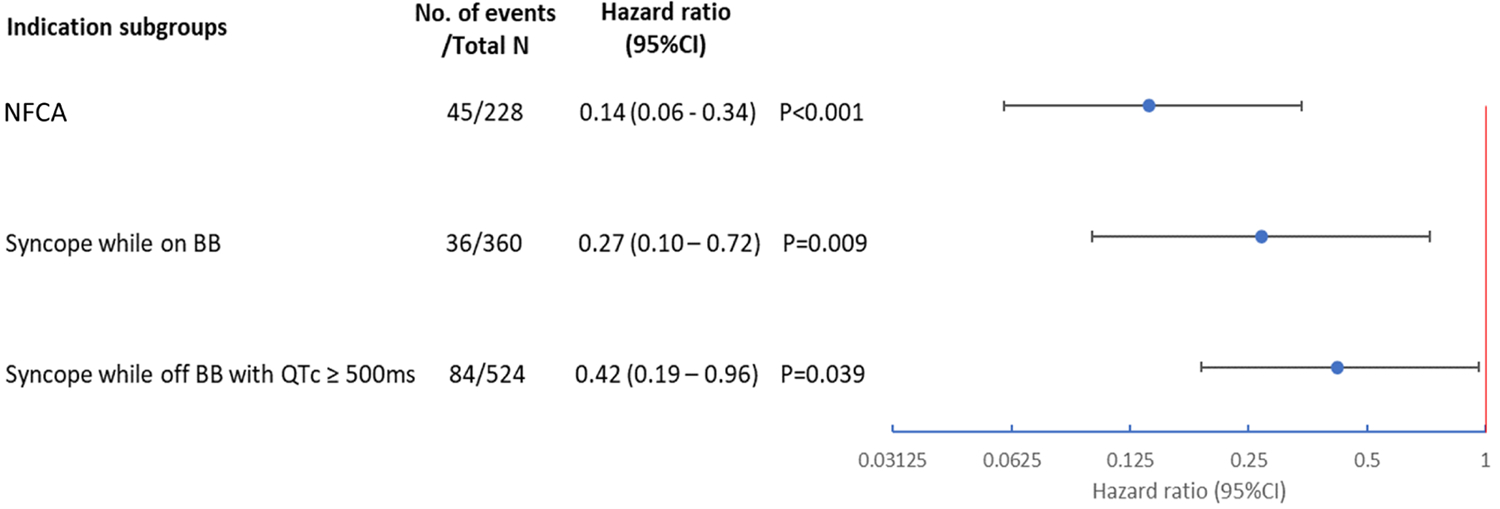

Results of analyses of subgroups by an ICD indication are shown in Central Illustration, part B. Compared to non-ICD patients, ICD patients had an 86% (HR=0.14, 95% CI: 0.06 – 0.34, p<0.001), 73% (HR=0.27, 95% CI: 0.10 – 0.72, p=0.009), and 58% (HR=0.42, 95% CI: 0.19 – 0.96, p=0.039) lower risk of post-indication all-cause mortality, among those with a history of NFCA, syncope occurring while on beta-blockers, and syncope occurring while off beta-blockers with a QTc ≥ 500ms, respectively. Among the 228 patients in the subgroup of NFCA, 6 died within a week, and 13 died within a month after the NFCA event. None of them ever received an ICD. Results were similar when using 1 month after NFCA (HR=0.12, 95% CI: 0.04–0.37) as time origin in analyses.

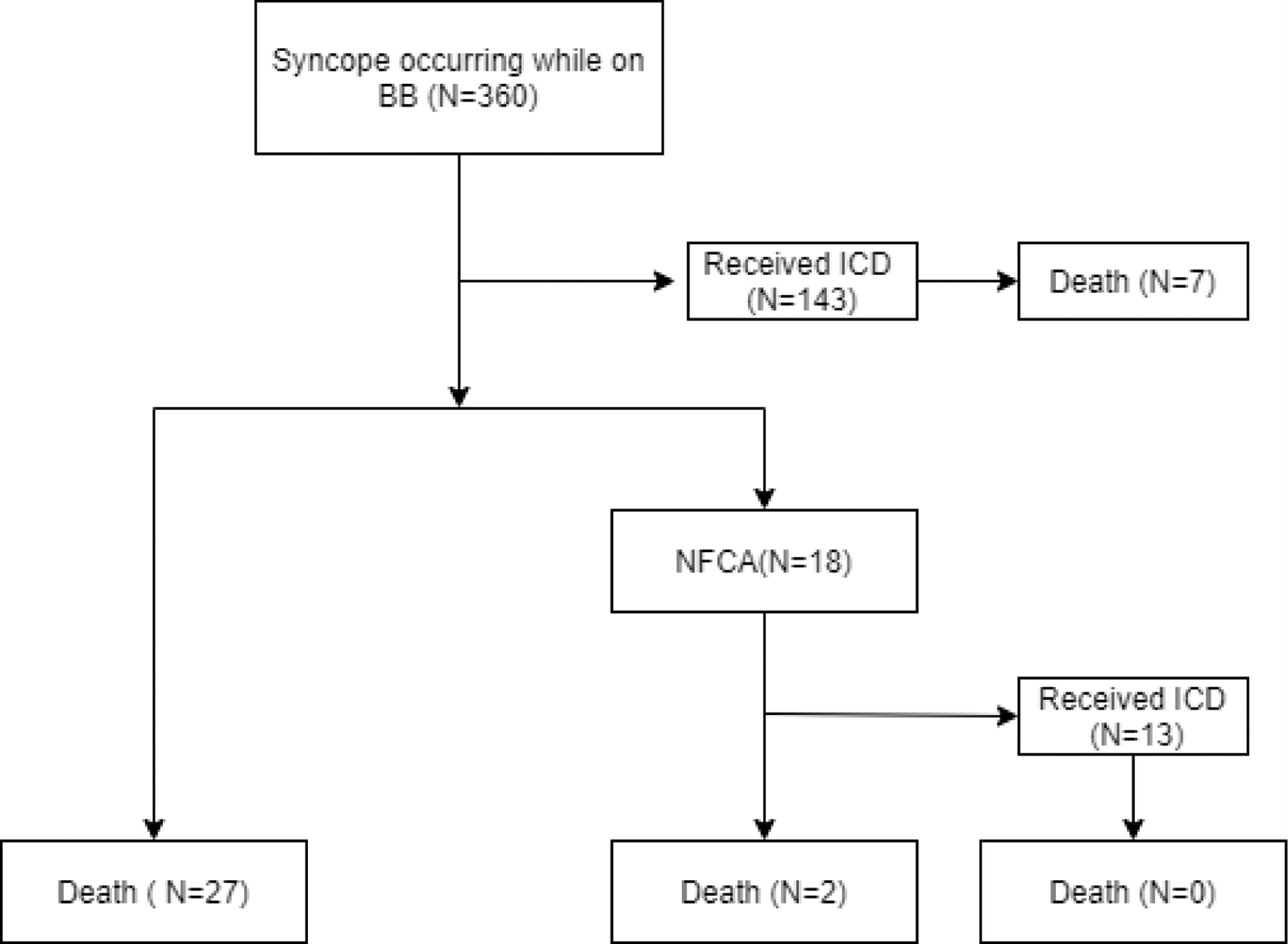

After censoring follow-up at the time of a higher-risk event, the HR for the subgroup of syncope while on beta-blockers attenuated slightly (from 0.27 to 0.36, Supplemental Table S4) but was still statistically significant (p=0.037). The HR for the subgroup of syncope while off beta-blockers with a QTc ≥ 500ms was essentially unchanged (from 0.42 to 0.41), although it was no longer statistically significant (p=0.157). To account for subsequent beta-blocker use in this subgroup, we performed another sensitivity analysis with additional adjustment for time-dependent beta-blocker treatment and observed a similar HR (0.47, 95% CI: 0.21 – 1.08), although statistical significance was only borderline (P=0.075). Descriptions of disease evolution for the two syncope subgroups are provided in Figure 2 and 3.

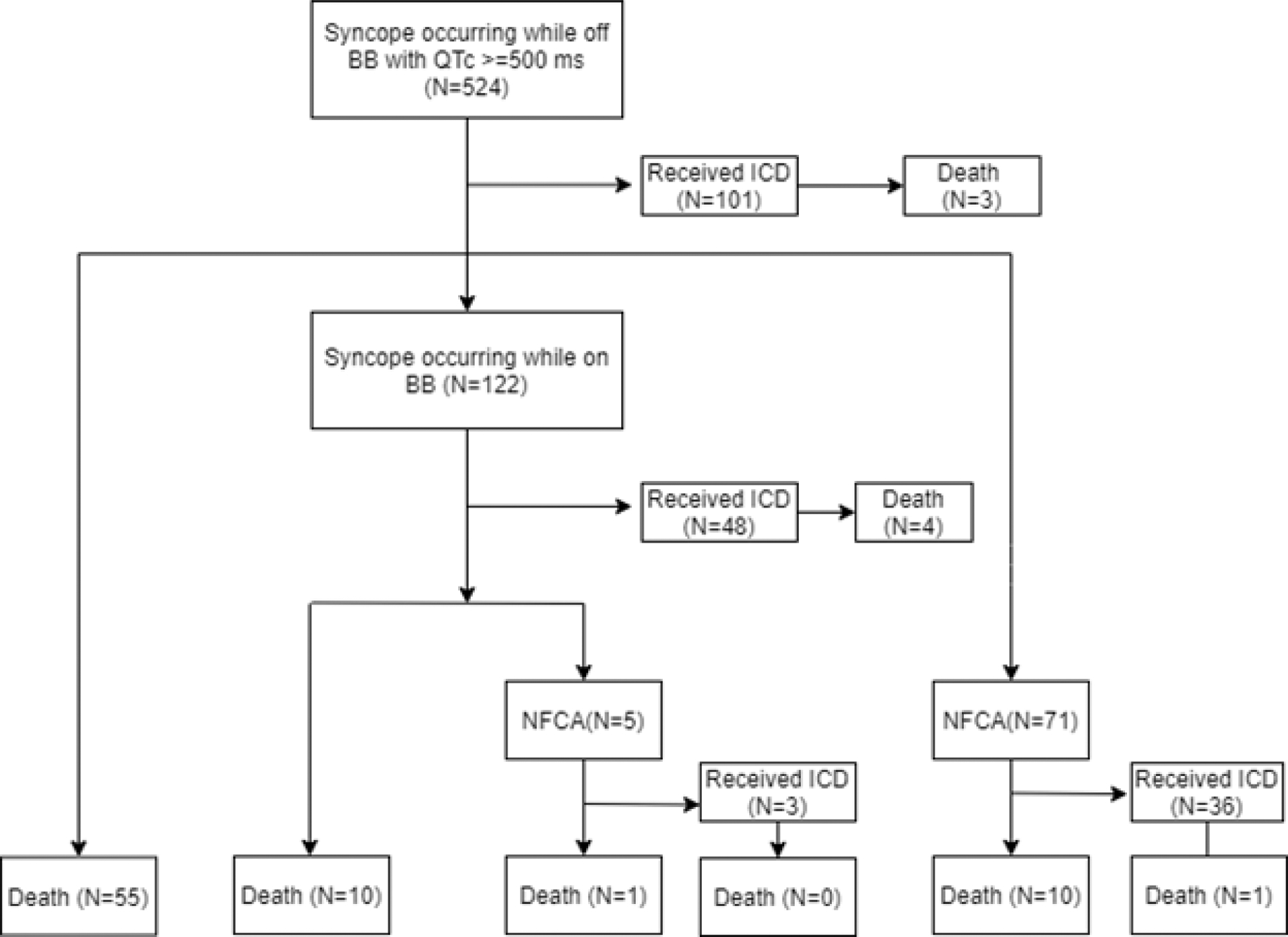

Figure 2. Evolution of patients with syncope occurring while on beta-blockers.

Among the 360 patients with a history of syncope occurring while on beta-blockers, 143 received an ICD before further developing NFCA and 7 of the 143 ICD patients died while on ICD. Among the rest of 217 patients who did not receive an ICD before further developing NFCA, 27 died and 18 later developed NFCA. BB: beta blockers; ICD: implantable cardioverter defibrillator; NFCA: non-fatal cardiac arrest.

Figure 3. Evolution of patients with syncope off beta-blockers and QTc ≥ 500ms.

Among the 524 patients with a history of syncope occurring while off beta-blockers and QTc ≥ 500ms, 101 received an ICD before further developing a higher-risk indication event and 3 of the 101 ICD patients died while on ICD. Among the rest of 423 patients who did not receive an ICD before further developing a higher-risk indication event, 55 died, 122 later developed syncope occurring while on beta-blockers, and 71 later developed NFCA. BB: beta blockers; ICD: implantable cardioverter defibrillator; NFCA: non-fatal cardiac arrest.

Risk and incidence rate of inappropriate ICD shocks and other ICD complications

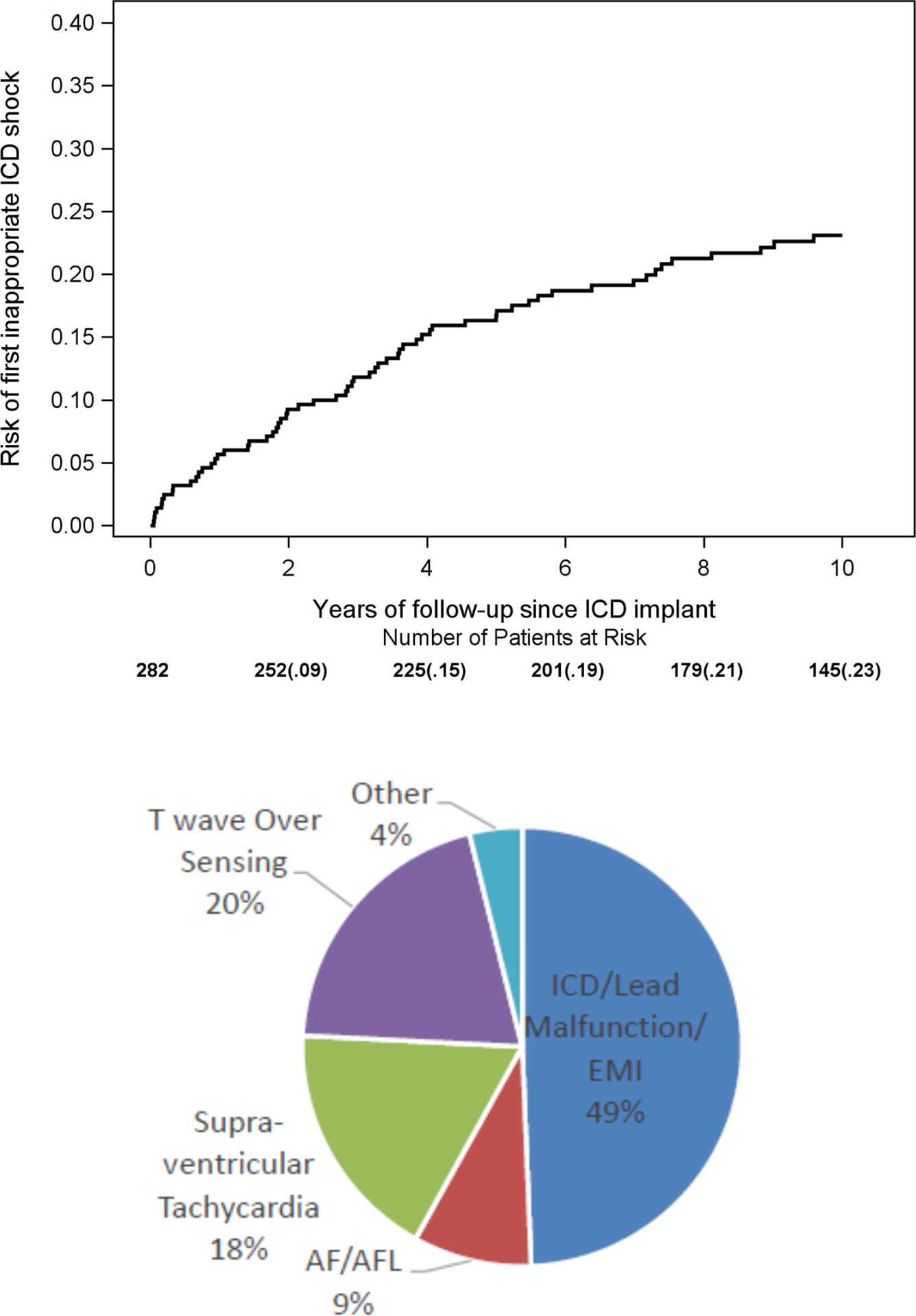

We included 282 of the 597 ICD patients who were also in the LQTS-ICD registry for this analysis. Included ICD patients generally had a higher LQTS risk profile compared to excluded ICD patients (Supplemental Table S5). The 10-year risk of inappropriate ICD shocks was 23% (Figure 4, top panel). To compare, we also estimated the 10-year risk of appropriate ICD shocks in the same population, and it was also 23% (Supplemental Figure S1), similar to the risk in the entire ICD population (22%, Figure 1).

Figure 4. Risk and reasons for inappropriate ICD shocks.

Top panel: Kaplan-Meier curve for the risk of first inappropriate ICD shock; Bottom panel: reasons for all 310 inappropriate ICD shocks during follow-up. We included 282 of the 597 ICD patients who were also in the LQTS-ICD registry for this analysis. ICD: implantable cardioverter defibrillator; EMI: electromagnetic interference; AF: atrial fibrillation; AFL: atrial flutter.

During a total follow-up of 3,697 person-years on ICD therapy, the rate (95%CI) of inappropriate ICD shocks when counting only the first shock per day was 3.1 (2.6 – 3.7), inappropriate ICD shocks when counting all shocks was 8.4 (7.5 – 9.4), appropriate shocks when counting only the first shock per day was 5.5 (4.8 – 6.3), and appropriate shocks when counting all shocks was 19.8 (18.4 – 21.3) per 100 person-years (Table 2). The most common mechanism for inappropriate shocks was generate/lead malfunction or electromagnetic interference (49%), followed by T wave over sensing (20%) and supra-ventricular tachycardia (18%), with atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter (9%) and others (4%) being the least common mechanisms (Figure 4, bottom panel).

Table 2.

Incidence Rate of ICD events among 282 LQTS Patients Enrolled in the LQTS-ICD Registry.

| Events | Number of events | Number of patients | Percentage of patients with event | Incidence rate (95%CI) (No. of events per 100 person-years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appropriate ICD shocks | 24.1 | |||

| Only count the first shock per day | 204 | 68 | 5.5 (4.8 – 6.3) | |

| Count all shocks | 731 | 68 | 19.8 (18.4 – 21.3) | |

| ICD complications | ||||

| Inappropriate ICD shocks | 24.8 | |||

| Only count the first shock per day | 114 | 70 | 3.1 (2.6 – 3.7) | |

| Count all shocks | 310 | 70 | 8.4 (7.5 – 9.4) | |

| Lead fracture/dislodgement | 27 | 22 | 7.8 | 0.7 (0.5 – 1.1) |

| ICD-related Infection | 5 | 5 | 1.8 | 0.1 (0.1 – 0.3) |

| Generator dysfunction | 13 | 12 | 4.3 | 0.4 (0.2 – 0.6) |

Total follow-up was 3,697 person-years.

The Kaplan-Meier 10-year risks of lead fracture/dislodgement, ICD-related infections, and generator dysfunction that required surgical procedures were 7%, 2%, and 4%, respectively (Supplemental Figure S2). The rates of the above three complications were 0.7 (0.5 – 1.1), 0.1(0.1 – 0.3), and 0.4 (0.2 – 0.6) per 100 person-years, respectively.

We explored the risk of mortality associated with time-varying inappropriate ICD shocks in 282 ICD patients and did not observe a statistically significant association (HR=0.89, 95%CI: 0.28 – 2.80).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study that estimated the risk of mortality endpoints associated with time-dependent ICD therapy (allowed patients to go on and off ICDs over time) in the LQTS population. We found that ICD therapy was associated with a decreased risk of all-cause mortality, all-cause mortality before age 50, and SCD in the entire LQTS population. Furthermore, we also observed a decreased risk of all-cause mortality associated with ICD therapy in both patients with a history of NFCA, and patients with a history of syncope while on beta-blockers. This study provides population-based evidence on the survival benefit of ICD therapy in LQTS patients.

To date, only one study examined the effectiveness of ICD therapy for reducing mortality in the LQTS population. In this 2003 study, we included patients with a history of cardiac arrest or recurrent syncope while on beta-blockers, and observed a higher overall survival estimated by the Kaplan-Meier estimator in ICD patients compared to non-ICD patients (log rank p=0.070) (5). However, this study was subject to immortal time bias due to inappropriate exclusion of the pre-ICD follow-up period in the ICD group, which may have led to an overestimate of the survival benefit of ICD therapy (10). To improve the study design, we currently analyzed ICD as a time-dependent variable, which minimized immortal time bias and provided a more accurate classification of the at-risk time by ICD status. Furthermore, our current study had longer follow-up with a larger number of deaths (N=389 vs. 27) and more rigorous control for confounding compared to the previous study. In the analyses of all LQTS patients, after adjusting for major LQTS prognostic factors, medications (including beta-blockers), decade of births, and comorbidities (for the all-cause mortality endpoint only), having an ICD was associated with more than 70% risk reduction for all-cause mortality before age 50 (HR=0.29, 95% CI: 0.14–0.61) and SCD (HR=0.22, 95% CI: 0.09–0.55) compared to not having an ICD. The risk reduction associated with ICD therapy for all-cause mortality was 46% (HR=0.54, 95% CI: 0.34–0.86). These findings support ICD therapy as an effective treatment for LQTS patients.

In the analyses of indication subgroups, we further separated patients with NFCA and patients with syncope while on beta-blockers. In each of the two subgroups, we observed a statistically significantly lower risk of all-cause mortality in ICD patients compared to non-ICD patients (HR=0.14, 95%CI: 0.06 – 0.34; and HR=0.27, 95%CI: 0.10 – 0.72; respectively). Based on current practice guidelines, ICD implantation is recommended in LQTS patients with a history of NFCA (Class I indication) and should be considered in patients with a history of syncope and/or ventricular tachycardia while on beta-blockers (Class IIa indication) (7–8). However, given the lack of evidence from comparative effectiveness studies, these guideline recommendations were primarily based on expert opinions and risk stratification studies (11–16). Our study was the first to compare the risk of mortality between ICD and non-ICD patients in these two indication subgroups separately, thus providing direct evidence supporting these recommendations.

Another subgroup of clinical interest is patients with syncope while off beta-blockers and a significant QTc prolongation (≥ 500ms). Based on current practice guidelines, this group of patients should be treated with beta-blockers first (7,8). Treatment intensification to ICD therapy is controversial. Our study showed a 58% (95% CI: 4% – 81%) risk reduction of all-cause mortality associated with having an ICD in this subgroup. The magnitude of this risk reduction remained similar (59%, Supplemental Table S3) even after we censored follow-up at the time of a higher-risk event (i.e., NFCA or syncope while on beta-blockers) later. However, statistical significance was lost after the censoring (P=0.157), likely due to the reduced number of deaths after the censoring (from 84 to 58). Further adjustment for time-dependent beta-blocker use did not attenuate the association to close to null. Rather, we still observed a trend toward a 53% risk reduction (HR=0.47, 95%CI: 0.21 – 1.08, P=0.075), suggesting that the protective effect of ICD therapy was likely independent of beta-blocker treatment. Furthermore, without ICD intervention, this group of patients had a 4.3% 5-year risk of developing NFCA or death while on beta-blockers prior to age 50 (Supplemental Figure 3). Given that the risk of disease progression despite beta-blocker treatment was not negligible, these patients may benefit from early ICD therapy.

Besides benefits, risk of adverse events is another important aspect to consider during the clinical decision-making process of ICD implantation, which has not been well studied in the LQTS population (6,17–19). In the 282 patients enrolled in both the LQTS Registry and LQTS-ICD Registry, risks of major ICD complications requiring lead- or generator-related surgical procedures were generally low (a 10-year risk of 7%, 2%, and 4% for lead fracture/dislodgement, infection, and generator dysfunction, respectively). Only 6 patients experienced recurrent major complications. Regarding ICD shocks, we observed a 23% 10-year risk of a first inappropriate ICD shock, which was the same as that of first appropriate ICD shocks (i.e. 23%). However, rates of inappropriate shocks, counting the first shock per day and counting all shocks, were both lower than those of appropriate shocks (3.1 vs. 5.5 and 8.4 vs. 19.8 per 100 person-years, respectively). These findings suggest that overall ICD therapy delivered more appropriate shocks than inappropriate shocks. They also suggest that focusing only on the first shock could lead to an incomplete understanding of the benefit and risk of ICD therapy in terms of shocks.

On the other hand, a 23% 10-year risk of first inappropriate ICD shocks was not negligible. A further investigation of mechanisms for inappropriate ICD shocks showed that lead malfunction, T-wave over-sensing, and supraventricular tachycardia were common mechanisms in our LQTS population. These findings of mechanisms were generally consistent with other LQTS studies, but they were different from studies of heart failure patients (6,17–22). In heart failure patients, atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter was more common and T-wave over-sensing was less common (19–21). Inappropriate ICD shocks can be reduced by improving ICD programming (21,23). However, current practice guidelines of optimal ICD programming were established primarily based on data of heart failure patients (23), which may not be completely applicable to LQTS patients given the difference in ECG features (e.g. T wave morphology) and mechanisms of inappropriate ICD shocks between the two populations. Therefore, more studies are needed to investigate optimal arrhythmia detection algorithms (to reduced T wave over-sensing) and ICD programming specifically for LQTS patients to reduce potential negative consequences of inappropriate ICD shocks (e.g. myocardium injury, pain, reduced quality of life, etc.) in this patient population.

Several limitations of our study should be considered when interpreting our findings. First, we included retrospective data collection period (i.e. before enrollment) in our follow-up to maximize the number of mortality endpoints. The quality of data collected during the retrospective period may not be as good as the prospective period. Nevertheless, the accuracy of ICD-related operations (documented in medical records) and mortality assessment was unlikely affected by retrospective recall, and sensitivity analysis of the entire population using enrollment as time zero gave similar results Second, for the subgroup with a QTc ≥ 500ms who developed syncope while off beta-blockers, the protective association of ICD with all-cause mortality lost statistical significance after censoring follow-up at the time of a higher-risk event. Therefore, we were not able to conclude that ICD therapy was protective for these patients before they further developed a higher-risk event, although the findings did support a long-term protective effect of ICDs for these patients. Third, our study did not have sufficient power to examine the effect of ICDs in subgroups defined by genotype or other detailed genetic information. Finally, the observational design cannot exclude residual confounding. However, we adjusted for a wide range of LQTS prognostic factors and LQTS treatments, and results were robust.

Conclusions

ICD therapy was associated with a decreased risk of all-cause mortality, all-cause mortality before age 50, and SCD in the LQTS population. ICD therapy was also associated with a decreased risk of long-term post-indication all-cause mortality in each of the three studied subgroups: 1) patients with a history of NFCA, 2) patients with a history of syncope while on beta-blockers, and 3) patients with a history of syncope while off beta blockers and a QTc ≥ 500ms.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspectives.

Competency in Patient Care and Procedural Skills:

Patients with long-QT syndrome (LQTS) who develop non-fatal cardiac arrest or syncope while taking β-adrenergic antagonist medication may benefit from implantation of an automatic defibrillator (ICD).

Translational Outlook:

More research is needed to establish optimal ICD programming parameters for patients with LQTS, and to verify the survival benefit and optimal timing of ICD therapy in patients with significant QT prolongation (i.e., QTc ≥ 500ms) who develop syncope off β-blocker medication.

Funding:

The study was performed with support from National Institutes of Health grants (No. HL-33843, HL-51618 and HL-123483).

Disclosures:

Dr. Zareba reports research grant support from Biotronik and LivaNova and consulting honoraria for Medtronic. The remaining authors have no disclosures.

List of Abbreviations

- ICD

Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator

- LQTS

Long QT syndrome

- SCD

sudden cardiac death

- NFCA

non-fatal cardiac arrest

- HR

hazard ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- BB

beta-blockers

- EMI

electromagnetic interference

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- AFL

atrial flutter

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Goldenberg I, Zareba W, Moss AJ. Long QT Syndrome. Curr Probl Cardiol 2008;33:629–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Semsarian C, Ingles J, Wilde AA. Sudden cardiac death in the young: the molecular autopsy and a practical approach to surviving relatives. Eur Heart J 2015;36:1290–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ et al. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2002;346:877–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB et al. Amiodarone or an Implantable Cardioverter–Defibrillator for Congestive Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 2005;352:225–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zareba W, Moss AJ, Daubert JP, Hall WJ, Robinson JL, Andrews M. Implantable cardioverter defibrillator in high-risk long QT syndrome patients. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2003;14:337–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwartz PJ, Spazzolini C, Priori SG et al. Who are the long-QT syndrome patients who receive an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator and what happens to them?: data from the European Long-QT Syndrome Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator (LQTS ICD) Registry. Circulation 2010;122:1272–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Priori SG, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: The Task Force for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2015;36:2793–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ et al. 2017. AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Oct 2;72(14):e91–e220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moss AJ, Schwartz PJ. 25th anniversary of the International Long-QT Syndrome Registry: an ongoing quest to uncover the secrets of long-QT syndrome. Circulation 2005;111:1199–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suissa S Immortal Time Bias in Pharmacoepidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 2007;167:492–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldenberg I, Moss AJ, Peterson DR et al. Risk factors for aborted cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death in children with the congenital long-QT syndrome. Circulation 2008;117:2184–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jons C, Moss AJ, Goldenberg I et al. Risk of fatal arrhythmic events in long QT syndrome patients after syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:783–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sauer AJ, Moss AJ, McNitt S et al. Long QT syndrome in adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:329–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Priori SG, Schwartz PJ, Napolitano C et al. Risk stratification in the long-QT syndrome. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1866–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ et al. Effectiveness and limitations of beta-blocker therapy in congenital long-QT syndrome. Circulation 2000;101:616–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spazzolini C, Mullally J, Moss AJ et al. Clinical implications for patients with long QT syndrome who experience a cardiac event during infancy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:832–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horner JM, Kinoshita M, Webster TL, Haglund CM, Friedman PA, Ackerman MJ. Implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy for congenital long QT syndrome: a single-center experience. Heart Rhythm 2010;7:1616–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biton Y, Rosero S, Moss AJ et al. Primary prevention with the implantable cardioverter-defibrillator in high-risk long-QT syndrome patients. Europace 2019;21:339–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borne RT, Varosy PD, Masoudi FA. Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator Shocks: Epidemiology, Outcomes, and Therapeutic Approaches. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:859–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daubert JP, Zareba W, Cannom DS et al. Inappropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shocks in MADIT II: frequency, mechanisms, predictors, and survival impact. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:1357–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moss AJ, Schuger C, Beck CA et al. Reduction in inappropriate therapy and mortality through ICD programming. N Engl J Med 2012;367:2275–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mönnig G, Köbe J, Löher A et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy in patients with congenital long-QT syndrome: a long-term follow-up. Heart Rhythm 2005;2:497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilkoff BL, Fauchier L, Stiles MK et al. 2015 HRS/EHRA/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus statement on optimal implantable cardioverter-defibrillator programming and testing. J Arrhythm 2016;32:1–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.