Vaccination is currently the strongest weapon in our fight against the COVID-19 pandemic. Understanding vaccine safety and immunogenicity is paramount to facilitate vaccine policies. SARS-CoV-2 might persist in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases for prolonged periods, and this persistence could lead to new virus variants.1 A third dose of COVID-19 vaccine is being administered by a few countries (eg, Israel and the USA) to their high-risk populations. This third dose will add to vaccine supply chain constraints the world is already facing. As of early October, 2021, approximately half the population of India had received at least one dose of a vaccine.2 Public health policies backed by scientific evidence are urgently needed to mitigate the dearth of vaccines.

There have been reports that a single dose of mRNA vaccine in people with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection induces an immune response similar to those who have received two doses of vaccine and no history of such infection.3, 4, 5, 6 Similar data have been put forward for the vector-borne vaccine ChAdOx1.7 We are not aware of such reports in patients with AIRD. We tested whether this hypothesis held true for AIRD patients on immunosuppressants.

We have been following up patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases who have had COVID-19 and those who have received COVID-19 vaccines who are registered with our centre (Centre for Arthritism and Rheumatism Excellence, Kochi, India). Serum and plasma samples from these patients were stored for research, with the patients' written informed consent.

We identified 30 consecutive patients who had documented SARS-CoV-2 infection in the past 12 months (August, 2020, to July, 2021), and had received one dose of the ChAdOx1 vaccine (infection plus vaccine). For comparison, we selected three more groups by manual matching for age, sex, and disease. These people were documented to have had COVID-19 in the past 6 months (February, 2021, to August, 2021), but had not received any vaccine (infection); received a single dose of the ChAdOx1 vaccine only; and completed two doses of ChAdOx1 vaccination as per prevalent national guidelines. In the last two groups, patients were queried about any past symptoms suggestive of COVID-19, and they were excluded from the vaccine-only groups if they reported any such symptoms. To avoid confounding due to different vaccines,8 we included only patients who had received the ChAdOx1 vaccine.

Serum was collected for all patients 4–6 weeks after infection and after vaccination, and stored at −80°C until processing. We quantified antibodies to the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 using the Elecsys assay (Roche, Switzerland), and viral neutralisation was assessed by SARS-CoV-2 sVNT Kit (GenScriptm, Piscataway, NJ, USA). If the inhibition was 30% or greater, neutralisation capacity was classified as positive.

The normality of data was confirmed by the Shapiro-Wilk test. Proportions was compared by the Fisher Exact test and antibody titres by independent sample t test after log transformation. A p value of less than 0·05 was considered significant. For multiple comparisons, p values were adjusted with Benjamin Hochberg corrections. All analyses and graphical representations were done using R, version 3.4.

Of the 120 patients in the four groups, the mean age was 55·8 years (SD 8·4) and 106 (88%) were female. Baseline characteristics, including drugs used, were similar across the four groups with 30 patients each (appendix p 1). In the infection plus vaccine group, the mean time between SARS-CoV-2 infection and the dose of COVID-19 vaccine was 120·9 days (SD 128·3), mirroring the Indian Government recommendation to vaccinate at least 3 months after COVID-19 infection. 23 (77%) of 30 had mild disease, five (17%) had moderate disease, and two (7%) had severe disease as per WHO classification.

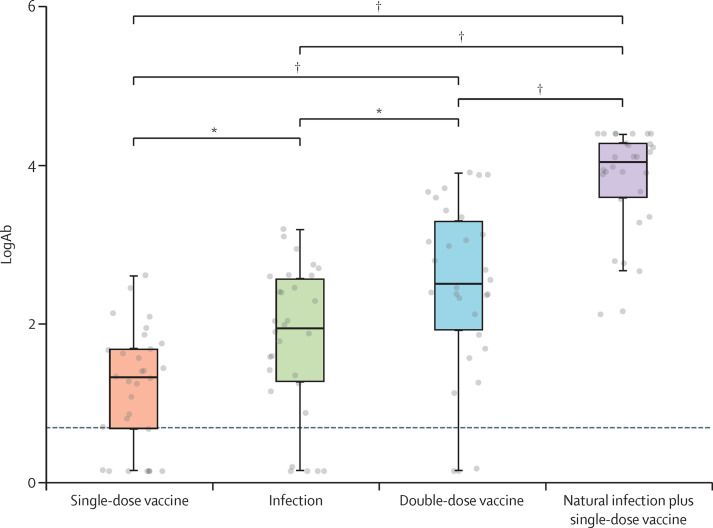

The infection plus vaccine group had the highest antibody titre compared with all other groups (p<0·0001; figure ). The antibody titres, seroconversion rates, and neutralisation percentages in the four groups are summarised in the appendix (p 2). There was 100% seroconversion in the infection plus vaccine group, compared with 90% in the double dose vaccine group (p<0·0001). The infection plus vaccine group also had higher neutralisation capacity (87% of individuals with at least 30% neutralisation) compared with the double dose vaccine group (60%; p=0·039). The neutralisation assay showed a moderate correlation (Pearson R 0·35; p<0·001) with antibody titres (appendix p 4). Neutralisation activity of more than 30% was associated with higher antibody titres (p<0·0001). A receiver operator curve analysis revealed that antibody titres above 212 IU predicted more than 30% neutralisation with a sensitivity of 81·5% and a specificity of 83·6% (appendix p 4).

Figure.

Log-transformed total antibodies titres against the Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 in four groups of patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases

With one dose of vaccine, post COVID-19 without vaccine, with two doses of vaccines, and with one dose of vaccine post COVID-19. *p<0·05. †p<0·001.

We had previously shown that patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases form anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies during COVID-19, equivalent to those in healthy controls.9 The current data show that this can be augmented with a single dose of vaccine. A major concern was whether a natural infection would produce specific neutralising antibodies. We have shown that antibodies produced with a single vaccine dose post infection have good neutralising capability in vitro.

There have been multiple reports in small cohorts about the effectiveness of a single dose of an RNA-based vaccine in patients who previously had COVID-19.3, 5, 6, 7 Based on these data, the concept of hybrid immunity induction is being explored in the context of vaccination post-natural infection.10 Individuals with previous exposure to SARS-CoV-2 demonstrated strong humoral and antigen-specific responses to the first vaccine dose, but muted responses to the second dose.6 A second dose might also induce some amount of tolerance after such a high immune response. With a worldwide shortage of vaccines, especially in low-income and middle-income countries, this strategy provides an alternative to conserve vaccines, at least in the short term. Earlier studies, however, had been carried out in health-care workers or healthy individuals; thus, our main concern was whether this strategy would work for patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases.

The major limitations of our work are that we have not looked at T-cell immunogenicity and that the study was not powered to look at the effects of immunosuppressants or disease activity. The neutralisation assay did not include responses to variants such as B.1.167.2. Another limitation was the small number of participants.

Thus, in this group of patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases who have previously had COVID-19, a single dose of vaccine provided a higher humoral response than did two doses of vaccine in infection-naive patients. This concept of hybrid immunity needs to be recognised and used in planning vaccination policies.

SA had received honorarium as speaker from Pfizer, Dr Reddy's, Cipla, and Novartis unrelated to this Comment. All other authors declare no competing interests. Data will made be available by PS and AP on reasonable request. PS and AP had direct access to the data and confirm its validity. Patients and the lay public were not directly involved in the planning of the study. All procedures performed in this study was conducted after acquiring ethics approval from Sree Sudheendra Medical mission (IEC/2021/35). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Choi B, Choudhary MC, Regan J, et al. Persistence and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in an immunocompromised host. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2291–2293. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2031364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India. Home. https://www.mohfw.gov.in/

- 3.Ebinger JE, Fert-Bober J, Printsev I, et al. Antibody responses to the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine in individuals previously infected with SARS-CoV-2. Nat Med. 2021;27:981–984. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01325-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeewandara C, Kamaladasa A, Pushpakumara PD, et al. Immune responses to a single dose of the AZD1222/Covishield vaccine in health care workers. Nat Commun. 2021;12 doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24579-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abu Jabal K, Ben-Amram H, Beiruti K, et al. Impact of age, ethnicity, sex and prior infection status on immunogenicity following a single dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine: real-world evidence from healthcare workers, Israel, December 2020 to January 2021. Euro Surveill. 2021;26 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.6.2100096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krammer F, Srivastava K, Alshammary H, et al. Antibody responses in seropositive persons after a single dose of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1372–1374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2101667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sasikala M, Shashidhar J, Deepika G, et al. Immunological memory and neutralizing activity to a single dose of COVID-19 vaccine in previously infected individuals. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;108:183–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shenoy P, Ahmed S, Paul A, et al. Inactivated vaccines may not provide adequate protection in immunosuppressed patients with rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221496. published online Oct 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shenoy P, Ahmed S, Shanoj KC, et al. Antibody responses after documented COVID-19 disease in patients with autoimmune rheumatic disease. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40:4665–4670. doi: 10.1007/s10067-021-05801-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crotty S. Hybrid immunity. Science. 2021;372:1392–1393. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.