Abstract

Objectives

We aimed to identify the concerns, current implementation status and correct usage, and factors inhibiting implementation and correct use of a COVID-19 contact tracing application among the ordinary citizens in Japan.

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study based on an internet survey completed by 2013 participants who were selected among registrants of an Internet research company between September 8 and 13, 2020.

Methods

Participants completed an online survey that included thoughts and concerns about the application, status of use, and questions about whether the application was being used correctly. We performed multiple logistic regression analysis to clarify the association between the use of the app and sociodemographic factors and user concerns.

Results

Of the 2013 respondents, 429 (21.3%) participants reported using this application, but only 60.8% of them used it correctly. The percentage of those having some concerns about the application ranged from 45.9% to 75.5%, with the highest percentage being ‘doubts about effectiveness of apps for preventing spread of infection’. Multiple logistic regression analysis revealed, the main concerns inhibiting application use were insufficient knowledge of how to use it, privacy concerns, doubts about the effectiveness of the app, and concerns about battery consumption and communication costs. Additionally, the prevalence of the application was lower for lower-income individuals.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that income may create inequalities in the efficacy and effectiveness of COVID-19 contact tracing applications. Awareness activity strategies to dispel such concerns and support low-income individuals may be needed.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pandemic, Personal protective measures, Contact tracing application, Public health

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Many citizens have numerous concerns about COVID-19 contact tracing apps.

-

•

Some concerns about COVID-19 contact tracing apps hinder the implementation of apps.

-

•

The prevalence of the application was lower for people with lower income.

-

•

Income may create inequalities in the efficacy and effectiveness of the apps.

-

•

Only 60.8% of COVID-19 contact tracing app users used it correctly.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is a public health threat [1]. Contact tracing is a fundamental public health intervention to control and contain severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic [2,3].

Contact tracing applications (apps) for smartphones have been attracting attention as a new method for COVID-19 contract tracing [4,5]. Conventional contact tracing methods use patient interviews and contact verification to check the social encounters of infected individuals [6]. Despite this being a stringent method, contact tracing may be insufficient in situations where infected individuals are uncooperative or unable to avail themselves for an interview for whatever reasons, such as severe health conditions. Additionally, it is generally laborious and requires a lot of time [7]. COVID-19 contact tracing apps could automate the process of tracking people’s movements and notify potentially infected people at the earliest possible stage [8]. Although there has been much debate concerning the utility of these apps, they have been introduced globally [[9], [10], [11]]. For contact tracing apps to work effectively, it must be used by a large number of the population, but a survey conducted by a private-sector company revealed that as of July 2020, the use rate for these apps was around 20% even in countries with the highest rates, and only about 9% on average [10]. To promote and increase the utilization of COVID-19 contact tracing applications, additional activities are essential. However, to do this, it is necessary to first identify the underlying factors that might determine the public’s decision-making to use or avoid these apps [2]. Further, Bluetooth-based apps rely on the user to activate the Bluetooth feature for it to function properly, yet it is unclear whether individuals possess such knowledge to use apps correctly.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to identify the concerns, current implementation status and correct usage, and factors inhibiting implementation and correct use of a COVID-19 contact tracing application among the Japanese people.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

This was a cross-sectional study utilizing data obtained from the first and sixth waves of a longitudinal survey that was initially conducted to clarify the implementation of personal protective measures by the general Japanese population during the COVID-19 pandemic [12]. This longitudinal survey was started on February 25, 2020, and follow-up surveys were conducted approximately every six weeks. Each wave survey mainly included only questionnaires on the implementation and thoughts of personal protective measures, and no interventions were provided to participants. The questionnaire for the follow-up survey was changed slightly for each survey, because over time, various new information, scientific findings, and social issues related to COVID-19 became available. The socio-demographic factors and the contact tracing app were only surveyed in the first wave and sixth wave, respectively. The study participants were recruited from those registered with a Japanese online research service company, MyVoice Communication, Inc., which had approximately 1.12 million registered participants as of January 2020. In the first wave of the longitudinal survey completed on February 25, 2020, we collected data from 2400 men and women aged 20–79 years (sampling by sex and 10-year age groups; 12 groups, n = 200 in each group) who were living across seven prefectures in the Tokyo metropolitan area. The online research service company randomly chose potential respondents from the registered participants. A total of 8156 registrants were invited by email to participate in the survey. The questionnaires were placed on a secured website and potential respondents received a specific URL in their invitation email. When the number of participants who voluntarily responded to the questionnaire reached 200 in each group, no more responses were accepted from that group. Data were obtained from 2400 participants in the first wave of the survey. In the sixth wave of the survey, the online research company contacted these 2400 participants by email to participate in a survey on September 8, 2020. Similar to the first wave, the questionnaires were placed on a secured website and potential respondents responded to the questionnaire by accessing the specified URL in their email. Participation was voluntary. The response cut-off date was September 13, 2020. Reward points valued at 50 yen were provided as incentives for participation (approximately 0.5 US dollars [USD] as of September 2020).

2.2. Assessment of use of a COVID-19 contact tracing application

In this study, we evaluated the usage of the COVID-19 Contact Confirming Application (COCOA), a COVID-19 contact tracing application developed by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and introduced on June 19, 2020 for use by citizens [11]. COCOA uses Bluetooth like many other COVID-19 contact tracing applications [8]. COCOA does not require registration of any personal information and does not record any personal information. It can be used with just a simple initial setup, such as accepting the user policy [11]. The application will record anonymous contact information from the opposite smartphone when one COCOA-installed smartphone comes in close proximity (within 1 m) with another COCOA-installed smartphone for 15 min or more. If COVID-19 is diagnosed in one of the smartphone owners, a notification is sent via the Internet to the recorded contact persons in the app with whom the smartphone owner has been in contact. Although the health center and government do not know who received the notification, if a person who received the notification contacts a local health center it is possible to get tested for COVID-19 if the health center decides that it is necessary.

Participants responded “yes” or “no” to whether they owned a smartphone and whether they used the COCOA. Those who were using the COCOA were then asked “yes/no” questions about their smartphone setup for installing this app: 1) initializing the application, 2) keeping the smartphone turned on at all times, 3) always carrying the smartphone, and 4) keeping the Bluetooth function activated at all times. Appendix 1 shows the actual questions and response options translated from Japanese to English.

2.3. Assessment of concerns for contact tracing applications

Regarding concerns for contact tracing applications, the question item was developed based on concerns from the general population which were listed on the website of the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare as frequently asked questions about this application [13]. All participants rated their concerns for the following items regarding the COCOA on a 4-point bipolar scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree): 1) insufficient knowledge of how to use the application, 2) concerns about privacy, 3) security concerns, 4) doubts about the effectiveness of apps for preventing spread of infection, 5) would feel troubled if found to be in contact with an infected person, and 6) concerns about smartphone battery consumption and communication costs (Appendix 1). For the current study, a response of 3 or 4 was defined as “having concern” about that matter.

2.4. Assessment of sociodemographic factors and trust in the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

In the first wave of the survey, participants provided their sex, age, smoking status (smokers/non-smokers), underlying diseases (heart disease, respiratory disease, kidney disease, diabetes, and hypertension) (yes/no), marital status (not married/married), employment status (working/not working), and residential area (metropolitan area [Tokyo, Kanagawa, Saitama, or Chiba]/nonmetropolitan area [Ibaraki, Tochigi, or Gunma]). The online research company provided categorized data on the following: living arrangement (with others/alone), educational attainment (university graduate or above/below), and annual personal income (less than 2 million yen [approximately 19,000 USD], 2-<4 million yen [19,000 -< 38,000], 4–6 million yen [38,000 -< 57,000], 6 million yen or more [57,000-]). In the sixth wave of the survey, participants indicated their level of trust in the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare ‘s COVID-19 strategy using a 7-point bipolar scale (1 = very low trust, 7 = very high trust, see Appendix 1). This question was adapted from the behavioral insights research for COVID-19 questionnaire published by the World Health Organization regional office in Europe [14]. In the current study, a response of 1–3, 4, 5–7, was defined as having low, middle, and high level of trust in the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, respectively.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The purpose of this study was to clarify the concern, implementation, and correct usage of a COVID-19 contact tracing application among Japanese citizens and factors inhibiting implementation and correct use of the application. We defined participants who responded that they were using the COCOA as ‘COVID-19 contact tracing application users’. Participant characteristics, level of trust in the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, and concerns regarding the contact tracing app were compared using a chi-square test between COVID-19 contact tracing application users and non-users. Regarding correct usage of the COVID-19 contact tracing application, we clarified the percentage of app users who were partially using the correct method and those who were using the correct method fully. ‘Correct app users’ were defined as those fully implementing the correct method of use.

To clarify the association between the use of the app and sociodemographic factors and user concerns, a multiple logistic regression analysis was performed. Only participants who had a smartphone were included in the logistic regression analysis. The dependent variable was set as a dichotomous variable coded as “1” if participants were COVID-19 contact tracing app users, and “0” if not. The independent variables included sex, age (20–29/30-39/40–49/50-59/60–69/70-79 years), smoking status (smokers/non-smokers), underlying diseases (yes/no), marital status (married/not married), employment status (working/not working), residential area (metropolitan area/nonmetropolitan area), living arrangement (with others/alone), educational attainment (university graduate or above/below), annual personal income level (<19,000 USD/19,000–38,000/38,000–57,000/≥57,000), trust level in the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare ‘s COVID-19 strategy (low/middle/high), insufficient knowledge of how to use the application (yes/no), concerns about privacy (yes/no), security concerns (yes/no), doubts about the effectiveness of apps in preventing spread of infection (yes/no), would feel troubled if found to be in contact with an infected person (yes/no), and concerns about battery consumption and communication costs (yes/no).

Furthermore, another multiple logistic regression analysis was conducted to clarify the association between the correct use of the app and sociodemographic factors. Only participants who were COVID-19 contact tracing application users were included in this logistic regression analysis. The dependent variable was set as a dichotomous variable coded as “1” if they were persons fully implementing the correct method of use, and “0” if not. The independent variables included sex, age, smoking, underlying diseases, marital status, employment status, residential area, living arrangement, educational attainment, and annual personal income level. For sensitivity analysis, these two multiple logistic regression analyses were also performed using forward stepwise selection.

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26 (IBM Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Two-tailed p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Initially, the online research company reached out to 2352 participants, after excluding participants who were not registered with the company at the time of the sixth wave of the survey (n = 48). A total of 2085 participants responded to the questionnaire. Sixty-one respondents were excluded due to missing data, and 11 were excluded for responding that they used the COCOA despite not owning a smartphone, resulting in a final participant count of 2013. There were 1682 smartphone users (83.6%) and 429 COVID-19 contact tracing application users which accounted for 25.5% of smartphone users (n = 1682), and 21.3% of all participants (n = 2013) (Table 1, Appendix 2). In a univariate analysis, the percentage of app users was significantly higher in men, employed, living in a metropolitan area, possessing high educational attainment, high annual personal income level, and high level of trust in the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. App users were also significantly less likely to have concerns about using contact tracing applications.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics, concerns regarding the COVID-19 contact tracing application, and level of trust in the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare among participants who owned a smartphone (n = 1682).

| Total |

COVID-19 contact tracing application users∗ |

COVID-19 contact tracing application non-users |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 1682 |

N = 429 (25.5%) |

N = 1253 (74.5%) |

||||

| n | n (%) | n (%) | p-valuea | |||

| Sex (men) | 811 | 232 | 28.6 | 579 | 71.4 | 0.005 |

| Age | ||||||

| 20–29 years | 231 | 54 | 23.4 | 177 | 76.6 | 0.571 |

| 30–39 years | 292 | 74 | 25.3 | 218 | 74.7 | |

| 40–49 years | 303 | 82 | 27.1 | 221 | 72.9 | |

| 50–59 years | 310 | 69 | 22.3 | 241 | 77.7 | |

| 60–69 years | 297 | 83 | 27.9 | 214 | 72.1 | |

| 70–79 years | 249 | 67 | 26.9 | 182 | 73.1 | |

| Smoking (smokers) | 252 | 59 | 23.4 | 193 | 76.6 | 0.408 |

| Underlying diseasesb (yes) | 424 | 108 | 25.5 | 316 | 74.5 | 0.985 |

| Marital status (married) | 1020 | 276 | 27.1 | 744 | 72.9 | 0.070 |

| Employment status (working) | 1118 | 313 | 28.0 | 805 | 72.0 | 0.001 |

| Residential area (metropolitan areac) | 1533 | 403 | 26.3 | 1130 | 73.7 | 0.018 |

| Living arrangement (with others) | 1364 | 341 | 25.0 | 1023 | 75.0 | 0.325 |

| Educational attainment (university graduate or above) | 912 | 261 | 28.6 | 651 | 71.4 | 0.001 |

| Annual personal income | ||||||

| <2 million yen [approximately 19,000 USD] | 702 | 146 | 20.8 | 556 | 79.2 | <0.001 |

| 2-<4 million yen [19,000 -< 38,000] | 430 | 101 | 23.5 | 329 | 76.5 | |

| 4-<6 million yen [38,000 -< 57,000] | 274 | 81 | 29.6 | 193 | 70.4 | |

| ≥6 million yen or more [57,000-] | 276 | 101 | 36.6 | 175 | 63.4 | |

| Trust in the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s strategy for COVID-19d | ||||||

| Low | 434 | 93 | 21.4 | 341 | 78.6 | 0.039 |

| Middle | 613 | 156 | 25.4 | 457 | 74.6 | |

| High | 635 | 180 | 28.3 | 455 | 71.7 | |

| Concerns about COVID-19 contact tracing applicatione | ||||||

| Insufficient knowledge of how to use the application (Yes) | 703 | 74 | 10.5 | 629 | 89.5 | <0.001 |

| Concerns about privacy (Yes) | 1056 | 152 | 14.4 | 904 | 85.6 | <0.001 |

| Security concerns (Yes) | 1097 | 168 | 15.3 | 929 | 84.7 | <0.001 |

| Doubt about the effectiveness of apps for preventing spread of infection (Yes) | 1275 | 248 | 19.5 | 1027 | 80.5 | <0.001 |

| Would feel troubled if found to be in contact with an infected person (Yes) | 855 | 185 | 21.6 | 670 | 78.4 | <0.001 |

| Concerns about smartphone battery consumption and communication costs (Yes) | 829 | 140 | 16.9 | 689 | 83.1 | <0.001 |

∗Participants who responded they are using the Japanese COVID-19 contact tracing application (COCOA).

p-value was calculated using chi-square test.

Underlying diseases included heart disease, respiratory disease, kidney disease, diabetes, and hypertension.

Metropolitan area included Tokyo, Kanagawa, Saitama, and Chiba prefectures.

Participants responded using a 7-point scale to show the level of trust they had in the government’s strategy for COVID-19 (1 = very low trust, 7 = very high trust). When a participant responded with 1–3, 4, or 5–7 on the scale, level of trust in the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare was defined as low, moderate, or high, respectively.

Answers were assessed on a 4-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree). A response of 3 or 4 was defined as “having concern” about that matter.

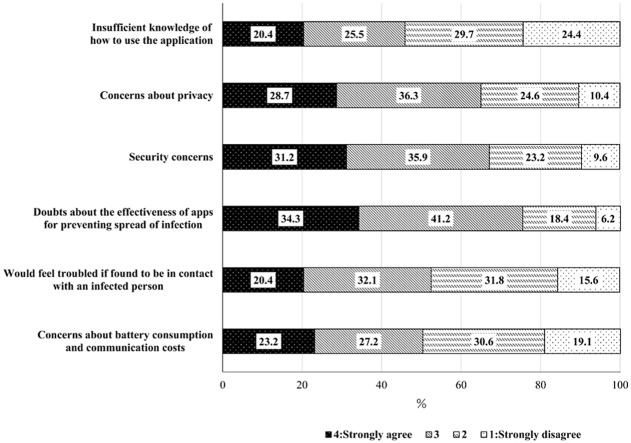

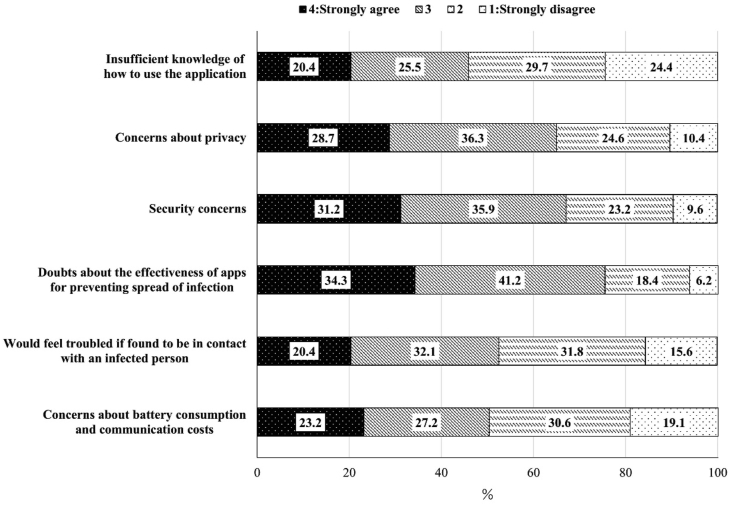

Fig. 1 shows participants’ concerns about the COVID-19 contact tracing application. Participants’ concern for each item ranged from 45.9% to 75.5%, with the highest percentage for ‘doubts about the effectiveness of apps for preventing spread of infection’.

Fig. 1.

Participants’ concerns regarding the COVID-19 contact tracing applicationFor

the current study, a response of 3 or 4 was defined as “having concern” about that matter.

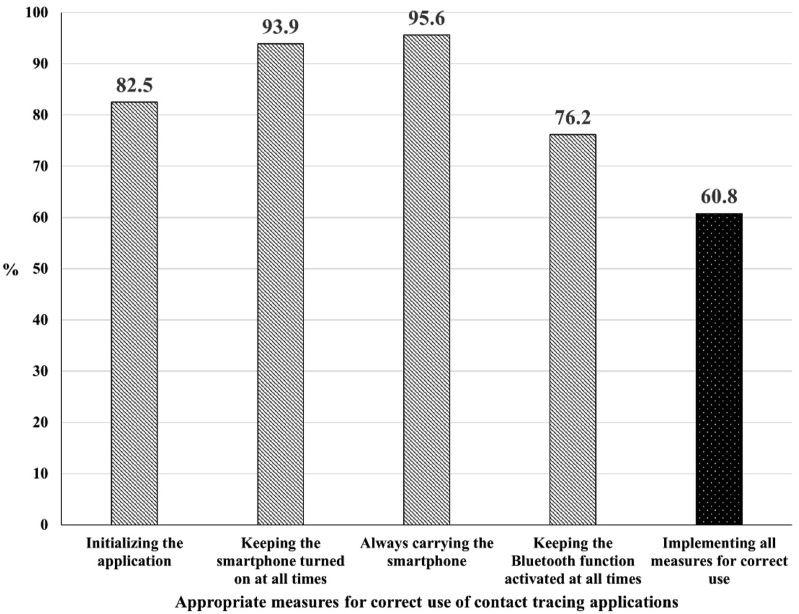

Fig. 2 shows the compliance rates for each measure of correctly using the contact tracing application among COVID-19 contact tracing application users (n = 429). The compliance rates ranged from 76.2% to 95.6%. The number of persons fully implementing the correct method of use was 261, which accounted for 60.8% of all app users (n = 429).

Fig. 2.

The correct usage of the contact tracing application among COVID-19 contact tracing application users (n = 429).

The percentage of contact tracing applications users who answered “Yes” for correct use is shown.

Table 2 shows the association between using the contact tracing application and socio demographic factors and opinions among the participants who had a smartphone (n = 1682). According to results of the multiple logistic regression analysis, working (Odds ratio [OR]: 1.46, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] 1.02–2.08), and would feel troubled if found to be in contact with an infected person (OR: 1.62, 95% CI: 1.22–2.14) were significant factors associated with those who used the application, while being in the age 50–59 range (OR: 0.52, 95% CI: 0.32–0.85), low annual personal income level (<2 million yen; OR:0.54, 95%CI: 0.34–0.87, 2-<4 million yen; OR: 0.55, 95%CI: 0.36–0.84), insufficient knowledge of how to use the application (OR: 0.32, 95% CI: 0.24–0.44), concerns about privacy (OR: 0.40, 95% CI: 0.26–0.60), doubts about the effectiveness of apps for preventing spread of infection (OR: 0.52, 95% CI: 0.39–0.69), and concerns about battery consumption and communication costs (OR: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.47–0.80) were significant factors for not using the application. The results of the sensitivity analysis also indicated that low income was a significant factor for not using the application (Appendix 3, Table A).

Table 2.

The association between using the COVID-19 contact tracing application and sociodemographic factors and opinions among participants who owned a smartphone (n = 1682).

| n | Odds ratioa (95% confidence interval) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic factor | ||

| Sex: | ||

| Men | 811 | Ref.f |

| Women | 871 | 1.09 (0.80–1.49) |

| Age: | ||

| 20–29 years | 231 | 0.79 (0.46–1.37) |

| 30–39 years | 292 | 0.80 (0.49–1.32) |

| 40–49 years | 303 | 0.71 (0.44–1.17) |

| 50–59 years | 310 | 0.52 (0.32–0.85)∗ |

| 60–69 years | 297 | 0.94 (0.60–1.46) |

| 70–79 years | 249 | Ref. |

| Smoking: | ||

| Smokers | 252 | 0.87 (0.60–1.25) |

| Non-smokers | 1430 | Ref. |

| Underlying diseasesb: | ||

| Yes | 424 | 0.92 (0.67–1.26) |

| No | 1258 | Ref. |

| Marital status (married) | ||

| Married | 1020 | 1.31 (0.92–1.87) |

| Not married | 662 | Ref. |

| Employment status: | ||

| Working | 1118 | 1.46 (1.02–2.08)∗ |

| Not working | 564 | Ref. |

| Residential area: | ||

| Metropolitan areac | 1533 | 1.53 (0.94–2.49) |

| Nonmetropolitan area | 149 | Ref. |

| Living arrangement: | ||

| With others | 1364 | 0.81 (0.55–1.21) |

| Alone | 318 | Ref. |

| Educational attainment: | ||

| University graduate level or above | 912 | 1.04 (0.79–1.36) |

| Below University graduate level | 770 | Ref. |

| Annual personal income | ||

| <2 million yen [approximately 19,000 USD] | 702 | 0.54 (0.34–0.87)∗ |

| 2-<4 million yen [19,000 -< 38,000] | 430 | 0.55 (0.36–0.84)∗ |

| 4-<6 million yen [38,000 -< 57,000] | 274 | 0.70 (0.46–1.06) |

| ≥6 million yen [57,000-] | 276 | Ref. |

| Trust in theMinistry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s strategy for COVID-19d | ||

| Low | 434 | Ref. |

| Middle | 613 | 1.07 (0.77–1.49) |

| High | 635 | 1.14 (0.82–1.58) |

| Concerns about COVID-19 contact tracing application e | ||

| Insufficient knowledge of how to use the application | ||

| Yes | 703 | 0.32 (0.24–0.44)∗ |

| No | 979 | Ref. |

| Concerns about privacy | ||

| Yes | 1056 | 0.40 (0.26–0.60)∗ |

| No | 626 | Ref. |

| Security concerns | ||

| Yes | 1097 | 0.86 (0.56–1.32) |

| No | 585 | Ref. |

| Doubt about the effectiveness of apps for preventing spread of infection | ||

| Yes | 1275 | 0.52 (0.39–0.69)∗ |

| No | 407 | Ref. |

| Would feel troubled if found to be in contact with an infected person | ||

| Yes | 855 | 1.62 (1.22–2.14)∗ |

| No | 827 | Ref. |

| Concerns about smartphone battery consumption and communication costs | ||

| Yes | 829 | 0.61 (0.47–0.80)∗ |

| No | 853 | Ref. |

∗p-value: <0.05.

Odds ratios were calculated and adjusted for all individual variables.

Underlying diseases included heart disease, respiratory disease, kidney disease, diabetes, and hypertension.

Metropolitan area included Tokyo, Kanagawa, Saitama, and Chiba prefecture.

Participants responded using a 7-point scale to show the level of trust they had in the government’s strategy for COVID-19 (1 = very low trust, 7 = very high trust). When a participant responded with 1–3, 4, or 5–7 on the scale, level of trust in the Ministry of Health was defined as low, moderate, or high, respectively.

Answers were assessed on a 4-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree). A response of 3 or 4 was defined as “having concern” about that matter.

Reference.

Table 3 shows the association between correct use of the contact tracing application and sociodemographic factors. Being in the age 60–69 range (OR: 2.57, 95% CI: 1.24–5.32), and having a high educational attainment (OR: 1.75, 95% CI: 1.11–2.75) were significant factors for those who used the app correctly. The results of the sensitivity analysis also indicated that having high educational attainment were significant factors for those who used the app correctly (Appendix 3, Table B).

Table 3.

Association between correct usage of the contact tracing application and sociodemographic factors among COVID-19 contact tracing application users (n = 429).

| n | Odds ratioa (95% confidence interval) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex: | ||

| Men | 232 | Ref.d |

| Women | 197 | 0.74 (0.44–1.25) |

| Age: | ||

| 20–29 years | 54 | 0.73 (0.30–1.74) |

| 30–39 years | 74 | 2.14 (0.96–4.79) |

| 40–49 years | 82 | 1.52 (0.70–3.29) |

| 50–59 years | 69 | 1.39 (0.63–3.06) |

| 60–69 years | 83 | 2.57 (1.24–5.32)∗ |

| 70–79 years | 67 | Ref. |

| Smoking: | ||

| Smokers | 59 | 1.02 (0.54–1.92) |

| Non-smokers | 370 | Ref. |

| Underlying diseasesb: | ||

| Yes | 108 | 0.85 (0.50–1.43) |

| No | 321 | Ref. |

| Marital status: | ||

| Married | 276 | 1.73 (0.96–3.13) |

| Not married | 153 | Ref. |

| Employment status: | ||

| Working | 313 | 0.96 (0.54–1.70) |

| Not working | 116 | Ref. |

| Residential area: | ||

| Metropolitan areac | 403 | 0.81 (0.33–1.98) |

| Nonmetropolitan area | 26 | Ref. |

| Living arrangement: | ||

| With others | 341 | 0.83 (0.43–1.63) |

| Alone | 88 | Ref. |

| Educational attainment: | ||

| University graduate level or above | 261 | 1.75 (1.11–2.75)∗ |

| Below university graduate level | 168 | Ref. |

| Annual personal income | ||

| <2 million yen [approximately 19,000 USD] | 146 | 0.57 (0.26–1.25) |

| 2-<4 million yen [19,000 -< 38,000] | 101 | 0.67 (0.33–1.36) |

| 4-<6 million yen [38,000 -< 57,000] | 81 | 0.76 (0.37–1.52) |

| 6 million yen or more [57,000-] | 101 | Ref. |

∗p-value: <0.05.

Odds ratios were calculated and adjusted for all individual variables.

Underlying diseases included heart disease, respiratory disease, kidney disease, diabetes, and hypertension.

Metropolitan area included Tokyo, Kanagawa, Saitama, and Chiba prefecture.

Reference.

4. Discussion

We set out to determine the concerns, implementation, and correct usage status of a COVID-19 contact tracing application among Japanese citizens and factors inhibiting implementation and correct use of the application. The percent of COVID-19 contact tracing application users in this study was 21.3%, and only 60.8% of app users used the application correctly. The percentage of those having some concerns about the COCOA ranged from 45.9% to 75.5%, with the highest percentage being ‘doubts about effectiveness of apps for preventing spread of infection’. Being in the age 50–59 range, not working, having a high annual personal income level, insufficient knowledge of how to use the application, concerns about privacy, doubts about the effectiveness of apps for preventing spread of infection, and concerns about smartphone battery consumption and communication costs were factors inhibiting the application. Additionally, the percentage of application users was found to be lower at lower income levels. Results from the current study indicated that there are various concerns about COVID-19 contact tracing applications among citizens, which inhibit them from using the app. In addition, some sociodemographic factors, such as low income, may hinder the accessibility of this application.

A survey of several private companies reported that the use of COVID-19 contact tracing apps in July 2020 was approximately 20% in countries with a high usage, and the average use was about 9% [10,15]. These values represent the number of downloads for the app divided by the population aged 14 years or older in each country. Regarding the COCOA, the Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare reported a total of approximately 16.39 million downloads as of September 8, 2020 [16], when this study was conducted. If we divide this by the Japanese population aged 14 years and above (112,025,000) [17], the rate is approximately 14.6%. The app use rate in this study was 21.3%, which was higher than expected. One reason for this may be that the smartphone ownership rate (83.6%) of participants in this study was higher than that of the average Japanese population (64.7%) [18]. This may be for a number of reasons, 1) the number of young participants in this study was higher than in the average Japanese population [19], and 2) since this study was an online survey, it is possible that a number of people were familiar with the Internet and smartphones. However, even though the percentage of app users in this study was higher than what has been generally reported in Japan, the prevalence of app users in this study was still merely 21.3%. Although it is yet to be determined exactly how much participation of the population is required for the COVID-19 contact tracing application to be sufficient enough in preventing the spread of infection [20], further promotion may be needed for a wider adoption of the app. In the current study, low income levels and unemployment were factors associated with incorrect use of the app. Therefore, it may be effective to provide education targeting these populations during a pandemic when time and resources may be limited.

Results also indicated that there were other various concerns about the COVID-19 contact tracing application among citizens. Among these concerns, insufficient knowledge of how to use the application, concerns about privacy, doubt about the effectiveness of apps for preventing spread of infection, and concerns about smartphone battery consumption and communication costs were factors associated with not using the app. It is documented on the website of the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare that the COCOA does not collect any private or personal information, and has low battery consumption as well as communication costs [11]. However, the current study revealed that many participants were concerned about these points. To increase the popularity of the COVID-19 contact tracing application, it may be important for the government to give a more extensive explanation for these concerns regarding the software.

In order for the COVID-19 contact tracing application to be used effectively, not only is it important to install it, but it is very important for one to use it correctly. However, only 60.8% of users were using the application correctly, and was particularly low among those with low educational attainment. While promoting the use of the app, it is crucial to raise awareness not only about installing the app but also on how to correctly use it.

Although there is concern that elderly people may not use the COVID-19 contact tracing application [21], the study found little association between age, the use of the application, and correct usage. However, since this study was an online survey, the participants may have been composed of people who already had some interest in technology compared with the general population. In particular, the difference between the elderly in our study and those within the general population may be large. Therefore, further studies are needed to clarify the association between age and use of COVID-19 contact tracing applications, since these results may be influenced by selection bias. On the other hand, low income level was a factor that inhibited the use of the application. According to the multiple logistic regression analysis regarding correct usage of the application, the point estimation of odds ratio was lower for people with lower income, although this was not statistically significant. The rise in health inequalities due to the COVID-19 pandemic has become an increasing concern [22]. Oronce et al. reported that in the U.S., states with higher income inequality experienced a higher number of deaths due to COVID-19 [23]. Furthermore, we also recently reported that the mental health of the Japanese people deteriorated from the early to the community transmission phases of COVID-19, and the degree of deterioration was more remarkable among those with low income [24]. The results of this study suggest that income may lead to inequality not only in health outcomes but also in the efficacy and effectiveness of COVID-19 contact tracing applications. Activities for promoting the use of COVID-19 contact tracing applications should include support that target low income populations, in addition to raising general public awareness of COVID-19 contact tracing applications.

There are some limitations that should be considered in our study. First, participants were recruited among people registered at a single online research company and very little is known about online communities and the characteristics of people involved [25]. According to the latest White Paper issued by the Japanese government in 2019 [18], the percentage of those who use the Internet regularly were approximately 95% for people in their 20s–50s, and 76.6% and 51.0% for those in their 60s and 70s, respectively. In addition, it has been reported that individuals who use the Internet regularly tend to have a higher income compared to non-users [18]. Therefore, participants in this study may be more educated or have a higher income than the average Japanese population. Additionally, when comparing the composition of age and sex for study participants to the latest population estimates reported by the Japanese government [19], there were more people in their 20s and fewer in their 40s in this study. Further, this study excluded 387 individuals from among 2400 participants in the first wave of the survey. Many of the excluded participants were in their 20s, had no underlying diseases, were not married, or lived in nonmetropolitan areas (data not shown). Considering these facts, the results of this study, such as percentages of COVID-19 contact tracing application users, should be interpreted with caution, as they may have been affected by selection bias, and may be overestimated. Second, this study was a self-reported evaluation, and these results may be affected by recall bias [26]. There may be a discrepancy between people’s perception of the correct use of the COCOA and the actual usage. Third, question items, such as concerns for contact tracing applications, were not validated. Finally, the results may not be applicable to other population groups as the prevalence and association may vary greatly due to different cultural, ethnic, and geographical backgrounds, when compared with those reported in the present survey. Despite these limitations, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to clarify actual concerns, implementation, and correct usage of a COVID-19 contact tracing application among Japanese citizens and factors inhibiting implementation and correct use of the application.

In conclusion, despite the availability of COVID-19 contact tracing applications, many citizens have numerous concerns about the usage of such applications, which hinder the spread of the application. Our study has also revealed that some COVID-19 application users do not use it correctly, and that differences in income may create inequalities in the accessibility and effectiveness of COVID-19 contact tracing applications. Therefore, awareness activities and strategies to dispel these concerns and offer support for low income individuals are necessary to make contact tracing applications accessible for any individual.

Funding

None.

Competing interests

None declared.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author contribution

MM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing-Original Draft, Visualization. IN: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-Review & Editing. RS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-Review & Editing. TN: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-Review & Editing. TH: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-Review & Editing. TT: Methodology, Resources, Writing-Review & Editing. YO: Methodology, Resources, Writing-Review & Editing. NF: Methodology, Resources, Writing-Review & Editing. HK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Writing-Review & Editing. SA: Methodology, Writing-Review & Editing. TK: Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing. HW: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-Review & Editing. SI: Conceptualization, Methodology. Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing-Original Draft, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tokyo Medical University, Tokyo, Japan (No: T2019-0234). Informed consent was obtained from all the respondents.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the participants who enrolled in this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhip.2021.100125.

Contributor Information

Masaki Machida, Email: machida@tokyo-med.ac.jp.

Itaru Nakamura, Email: task300@tokyo-med.ac.jp.

Reiko Saito, Email: jasmine@med.niigata-u.ac.jp.

Tomoki Nakaya, Email: tomoki.nakaya.c8@tohoku.ac.jp.

Tomoya Hanibuchi, Email: info@hanibuchi.com.

Tomoko Takamiya, Email: takamiya@tokyo-med.ac.jp.

Yuko Odagiri, Email: odagiri@tokyo-med.ac.jp.

Noritoshi Fukushima, Email: fukufuku@tokyo-med.ac.jp.

Hiroyuki Kikuchi, Email: kikuchih@tokyo-med.ac.jp.

Shiho Amagasa, Email: amagasa@tokyo-med.ac.jp.

Takako Kojima, Email: tkojima@tokyo-med.ac.jp.

Hidehiro Watanabe, Email: hw-nabe4@tokyo-med.ac.jp.

Shigeru Inoue, Email: inoue@tokyo-med.ac.jp.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.World Health Organization . 2020. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ivers L.C., Weitzner D.J. Can digital contact tracing make up for lost time? Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e417–e418. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30160-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keeling M.J., Hollingsworth T.D., Read J.M. Efficacy of contact tracing for the containment of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2020;74:861–866. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-214051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferretti L., Wymant C., Kendall M., Zhao L., Nurtay A., Abeler-Dorner L., et al. Quantifying SARS-CoV-2 transmission suggests epidemic control with digital contact tracing. Science. 2020;368:eabb6936. doi: 10.1126/science.abb6936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robert Hinch W.P., Nurtay Anel, Kendall Michelle, Wymant Chris, Hall Matthew. 2020. Effective Configurations of a Digital Contact Tracing App: A Report to NHSX.https://cdn.theconversation.com/static_files/files/1009/Report_-_Effective_App_Configurations.pdf?1587531217 [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization Contact tracing. 2017. https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/contact-tracing

- 7.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Contact tracing for COVID-19: current evidence, options for scale-up and an assessment of resources needed. 2020. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/COVID-19-Contract-tracing-scale-up.pdf

- 8.Zastrow M. Coronavirus contact-tracing apps: can they slow the spread of COVID-19? Nature. 2020 May 19 doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaughan A. The problems with contact-tracing apps. New Sci. 2020;246:9. doi: 10.1016/S0262-4079(20)30787-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.SensorTower . 2020. COVID-19 Contact Tracing Apps Reach 9% Adoption in Most Populous Countries.https://sensortower.com/blog/contact-tracing-app-adoption [Google Scholar]

- 11.Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare . 2020. Request to Install the COVID-19 Contact-Confirming Application.https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10900000/000647649.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12.Machida M., Nakamura I., Saito R., Nakaya T., Hanibuchi T., Takamiya T., et al. Adoption of personal protective measures by ordinary citizens during the COVID-19 outbreak in Japan. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;94:139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Contact tracing application Frequently Asked Questions. 2020. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/covid19_qa_kanrenkigyou_00009.html

- 14.World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe . 2020. Survey Tool and Guidance: Behavioural Insights on COVID-19.https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/publications/2020/survey-tool-and-guidance-behavioural-insights-on-covid-19 29 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Statista Adoption of government endorsed COVID-19 contact tracing apps in selected countries as of July 2020. 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1134669/share-populations-adopted-covid-contact-tracing-apps-countries/

- 16.Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare . 2020. COVID-19 Contact-Confirming Application.https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/cocoa_00138.html [Google Scholar]

- 17.Statistics Bureau of Japan Population Estimates October 1,2019 [in Japanese] 2019. https://www.stat.go.jp/data/jinsui/2019np/index.html

- 18.Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Japan White Paper on Information and Communications in Japan 2019. https://www.soumu.go.jp/johotsusintokei/whitepaper/eng/WP2019/2019-index.html

- 19.Statistics Bureau of Japan . 2020. Population Estimates by Age and Sex – February 1,2020 (Final Estimates)https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&toukei=00200524&tstat=000000090001&cycle=1&year=20200&month=23070907&tclass1=000001011678&result_back=1;%202020 July 1. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Science . 2020. COVID-19 Contact Tracing Apps Are Coming to a Phone Near You. How Will We Know whether They Work?https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/05/countries-around-world-are-rolling-out-contact-tracing-apps-contain-coronavirus-how [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rizzo E. COVID-19 contact tracing apps: the ’elderly paradox. Publ. Health. 2020;185:127. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.06.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bambra C., Riordan R., Ford J., Matthews F. The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2020;74:964–968. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-214401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oronce C.I.A., Scannell C.A., Kawachi I., Tsugawa Y. Association between state-level income inequality and COVID-19 cases and mortality in the USA. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020;35:2791–2793. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05971-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kikuchi H., Machida M., Nakamura I., Saito R., Odagiri Y., Kojima T., et al. Changes in psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: a longitudinal study. J. Epidemiol. 2020 doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20200271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright K.B. Researching internet-based populations: advantages and disadvantages of online survey research, online questionnaire authoring software packages, and web survey services. J. Computer-Mediated Commun. 2017;10:JCMC1034. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2005.tb00259.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coughlin S.S. Recall bias in epidemiologic studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1990;43:87–91. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.