Abstract

Background

Receiving a breast cancer diagnosis can be a turning point with negative impacts on mental health, treatment and prognosis. This meta-analysis sought to determine the nature and prevalence of clinically significant psychological distress-related symptoms in the wake of a breast cancer diagnosis.

Methods

Ten databases were searched between March and August 2020. Thirty-nine quantitative studies were meta-analysed.

Results

The prevalence of clinically significant symptoms was 39% for non-specific distress (n = 13), 34% for anxiety (n = 19), 31% for post-traumatic stress (n = 7) and 20% for depression (n = 25). No studies reporting breast cancer patients’ well-being in our specific time frame were found.

Conclusion

Mental health can be impacted in at least four domains following a diagnosis of breast cancer and such effects are commonplace. This study outlines a clear need for mitigating the impacts on mental health brought about by breast cancer diagnosis. CRD42020203990.

Keywords: oncology, anxiety; depression; psychological distress; post-traumatic stress; well-being

Subject terms: Breast cancer, Human behaviour

Background

Among women, breast cancer is the most common type of cancer, with more than 2 million cases globally in 2018 [1]. Breast cancer can change the course of one’s life due, among other things, to the immense uncertainties brought about by the course of the disease, the treatment, the prognosis, as well as the profound changes to body image [2, 3]. As a consequence, patients could experience difficulties in many important areas, such as their social relationships [2, 3].

This life-changing experience induces significant psychological distress for many patients [4]. Poor mental health can be caused or exacerbated by the diagnosis itself [5, 6]. For many survivors from primary or recurrent breast cancer, receiving the actual cancer diagnosis was the most difficult moment of the whole process [2, 7]. In recent years, the remission rates have increased up to 96% in North America for primary breast cancer [8]. This increase in breast cancer survival also means, however, that some survivors live with enduring poor quality of life and psychological distress [8].

In spite of several publications on this topic, the nature and frequency of psychological symptoms experienced by breast cancer patients remain unclear. In oncology, psychological distress is broadly defined as a negative experience of a cognitive, behavioural, emotional, social, spiritual or psychological nature interfering with the ability to cope with cancer [3, 9]. Distress experienced by cancer patients can range from mild (i.e., common feelings of vulnerability) to disabling and can manifest in various ways [4]. Some studies have shown the increased risk of stress-related disorders immediately after the diagnosis of breast cancer, highlighting that diagnosis and treatment are two distinct distressing periods that ought to be each studied [10]. Although diagnosis-specific distress is distinct from distress pertaining to the overall cancer experience, many existing studies do not make the distinction between reactions to the acute post-diagnosis phase and more global responses to cancer [4].

Diagnosis-specific distress in breast cancer patients persists and has implications for outcomes, including treatment adherence [4]. Three reviews suggest that symptoms of anxiety in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients are pervasive and persistent regardless of the course of cancer treatment [11–13]. Another review suggests that >22% of women develop depressive symptoms following their diagnosis of breast cancer [12]. Depressive symptoms assessed after a cancer diagnosis are associated with a poor prognosis and a higher risk of mortality [14]. Furthermore, there is evidence that the life-threatening nature of a breast cancer diagnosis can elicit peritraumatic distress (i.e., emotional, behavioural and physiological responses that occur during and immediately after a highly stressful event) [15–17] and symptoms congruent with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in up to 32% of the women afflicted [18, 19]. Although these results are striking and require attention, they nonetheless highlight that the majority of patients experience subclinical distress symptoms and cope with the diagnosis and treatments relatively well [20]. Specifically, one study showed that despite the presence of distress symptoms, many patients reported higher levels of well-being following diagnosis compared to pre-diagnosis [20, 21]. The severity of anxiety, depressive and trauma-related symptoms can lead to poorer quality of life, whereas perceived well-being could improve mental health outcomes [20] particularly as patients transition from the diagnostic to the treatment phase [22, 23]. Relatedly, it is important to further understand the risk and protective factors that lead to clinical or subclinical diagnosis-specific distress. However, studies so far have rarely focused on the specific and important turning point of the diagnosis.

Although empirical studies and systematic reviews point to a variety of mental health problems and different levels of well-being following a diagnosis of breast cancer, a quantitative account of the nature and frequency of such mental health problems and levels of well-being is lacking. The previously cited studies do not distinguish the pre-treatment and treatment phases, mixing newly diagnosed women with those undergoing treatment. It is important to isolate the moment following the diagnosis and ending just before treatments in order to better understand its impact on breast cancer patient’s mental health and thus adapt the interventions according to the phases of the cancer experience. This meta-analysis fills that gap by determining the nature and prevalence of clinically significant diagnosis-specific distress symptoms before the treatment begins in breast cancer patients.

Methods

The meta-analysis protocol is registered on PROSPERO (CRD42020203990).

Data collection

Ten databases were searched for published and unpublished studies: CINAHL, Clinicaltrial.org, Cochrane Central, Google Scholar, PTSDpubs, ProQuest, PsycInfo, PubMed, Research Gate and Web of Science. Keywords were chosen with the help of an academic librarian. We searched for the keywords [distress* or stress* or anxiety or anxious* or depress* or PTSD or peritraumatic distress/reactions or well-being] AND [breast cancer or breast neoplasm* or mammary neoplasm*] AND [diagnosis* or announcement or pre-treatment*] in the databases with no year constraint.

Literature screening

Inclusion criteria were developed based on literature search and discussions with the two senior authors. In order to be included, a study needed to: (1) measure depressive, anxiety, non-specific distress, peritraumatic distress or post-traumatic stress symptoms or well-being; (2) measure the symptoms after the diagnosis but before the beginning of treatments; (3) report data specifically for breast cancer patients; (4) use of a valid self-report measure or a structured interview; (5) present the results as the proportion of study participants scoring above the clinical threshold or cut-off scores; and (6) be written in English or French.

Data extraction

Articles whose title and abstract matched the inclusion criteria were exported to the Rayyan website [24] and divided according to symptom dimensions. Studies measuring several dimensions were included in multiple categories. Two team members independently selected the articles for inclusion based on the abstract. The consensus was achieved in 93% of cases. Disagreements were resolved by a senior author weighing in. Information was extracted from the article using the PRISMA checklist [25], and the exclusion criteria were applied. If a study did not clearly report that the data were collected before the cancer treatment started (n = 5), the corresponding author was contacted and given 30 days to respond. Two papers were thus excluded for lack of such a response.

Quality assessment

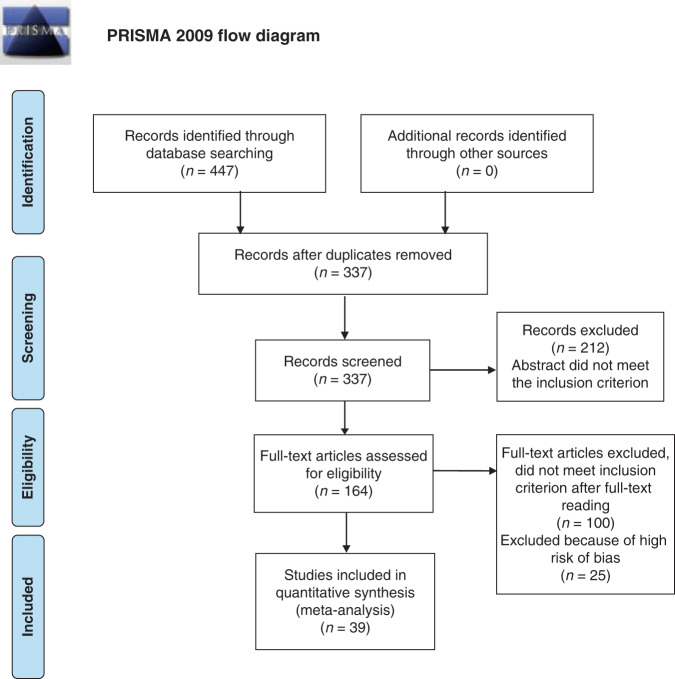

To assess the risk of bias, we used the tool from Hoy et al. [26] which evaluates the external and internal validity of studies but also the analysis bias. For each of the ten items, the evaluator chooses between a high, moderate or low bias rating [26]. Each study was evaluated by two independent raters. Disagreements (15%) were resolved by a senior author. Only papers with a low/moderate risk of bias were included in the final sample (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow diagram [63].

The figure shows the flow of information through the different phases our meta-analysis following PRISMA methodology [63].

Data analysis

A meta-analysis was performed using the RStudio statistical software. ‘Prevalence’ estimate of each symptom dimension was calculated by pooling the study-specific estimates using random-effect meta-analysis that accounted for heterogeneity among studies. The heterogeneity of the preliminary studies was evaluated and quantified with the I2 Cochrane test. The inverse variance method with the logit transformation was performed to stabilise the variance of each study’s proportion in order to get a better estimate of the summary proportion and its confidence interval (CI). Forest plots for the random-effect models were constructed. Linear regression tests of the funnel plot asymmetry as bias tests were conducted. We performed a sensitivity analysis to confirm the robustness of the results by conducting each meta-analysis multiple times, each time removing a different result (effect size) to see if the overall results remained similar. This was done to make sure that no effect size had too much influence on the resulting combined effect size. Finally, we conducted an exploratory meta-regression analysis using a mixed-effect model to examine if the time since diagnosis had an effect on the overall psychological symptom severity for all studies combined.

Results

Our final sample included 39 studies (see Fig. 1). The descriptive information is summarised in Table 1. As 19 studies reported more than one symptom dimension, they appear in more than one category. The definition of diagnosis varied between studies, such that distress symptoms were measured following the initial diagnosis of breast cancer (n = 15), following the pathological/clinical diagnosis (confirmed after surgery) (n = 12), or at an unspecified point (n = 12; see column “Diagnosis Definition” in Table 1). Linden et al. [27] was the only study reporting the prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms for women and men patients in breast cancer. However, we kept the study in our analyses since gender did not obscure the findings. For each symptom domain, the asymmetry linear regression tests and sensitivity analyses were nonsignificant, confirming that the analysis assumptions were satisfied.

Table 1.

Studies characteristics.

| Studies (n = 39) | Country | Target population sex (n total; mean age) | Symptom categories | Diagnosis definitiona | Instrument (cut-off scores or clinical threshold (CT)) | Time (mean days) of testing (post-diagnosis; pre-treatment) | Design | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andreu et al. [64] | Spain | Women (102; 50.5) | Distress | Pathological/clinical | BSI-18 (>63) | Not specified | Longitudinal | Moderate |

| Arnaboldi et al. [65] | Italy | Women (150; 47.0) |

Anxiety PTSD |

Announcement |

STAI (CT) IES (CT) |

30; not specified | Longitudinal | Low |

| Burgess et al. [66] | UK | Women (222; 48.4) |

Anxiety Depression |

Pathological |

SCID-anxiety (CT) CES-D (CT) |

Not specified | Cross-sectional | Low |

| Chang et al. [67] | USA | Women (110; 60.3) | Depression | Pathological/ clinical | BSI‐18 (> 60) | Not specified | Cross-sectional | Low |

| Cimprich [68] | USA | Women (74; 56.0) | Distress | Announcement | SDS (CT) | Not specified; 11 | Cross-sectional | Low |

| Cimprich & Ronis [69] | USA | Women (47; 64.0) | Distress | Pathological/ clinical | SDS (CT) | 16; 12 | Cross-sectional | Low |

| Cimprich et al. [70] | USA | Women (184; 54.6) | Distress | Announcement | POMS (CT) | Not specified; 18 | Cross-sectional | Low |

| Civilotti et al. [58] | Italy | Women (436; 57.2) |

Anxiety Depression Distress |

Announcement |

HADS-A (>8) HADS-D (>8) DT (CT) |

28; 14 | Cross-sectional | Low |

| Denieffe et al. [71] | Ireland | Women (94; 54.9) | Depression | Announcement | HADS-D (≥8) | 14; 10 | Prospective | Low |

| Farragher [72] | Ireland | Women (33; 51) |

Anxiety Depression |

Pathological/ clinical |

LSAA (>7) LSAD (>7) |

Not specified | Prospective | Low |

| Faye‐Schjøll & Schou-Bredal [73] | Norway | Women (367; 54.9) |

Anxiety Depression |

Pathological/ clinical |

HADS-A (≥8) HADS-D (≥8) |

Not specified | Longitudinal | Low |

| Galloway et al. [74] | USA | Women (60; 57.7b) |

Anxiety Depression |

Not specified |

STAI (CT) CES-D (CT) |

Not specified | Cross-sectional | Low |

| Gibbons et al. [75] | Ireland | Women (94; 57.2) |

Anxiety Depression Distress |

Announcement |

HADS-A (CT) HADS-D (CT) Cancer-related distress (CT) |

14; not specified | Cross-sectional | Low |

| Glinder & Compas [76] | USA | Women (76; 54.8) |

Depression Distress |

Pathological/ clinical |

SCL-90R-Depression (CT) SCL-90-R (CT) |

10; not specified | Prospective | Low |

| Hegel et al. [77] | USA | Women (236; 57.4) |

Anxiety Depression Distress PTSD |

Announcement |

PHQ-Anxiety (≥8) PHQ-9- Depression (>9) SCL-90R-Distress (>5) PC-PTSD (≥8) |

Not specified | Cross-sectional | Low |

| Hegel et al. [78] | USA | Women (345; 57.8) | Depression | Announcement | PHQ-9- Depression (≥7) | Not specified | Cross-sectional | Moderate |

| Henselmans et al. [79] | Netherlands | Women (171; 54.8) | Distress | Pathological/ clinical | GHQ-12 (≥2) | 12; not specified | Longitudinal | Low |

| Jones et al. [80] | USA | Women (6949; 62.7) | Depression | Not specified | CES-D (≥1.61) | Not specified | Cross-sectional | Low |

| Kaiser et al. [81] | Germany | Women (27; 53.2) |

Anxiety Depression |

Not specified |

HADS-A (CT) HADS-D (CT) |

Not specified | Cross-sectional | Low |

| Kant et al. [82] | Germany | Women (181; 53.0) | Distress | Pathological/clinical | GHQ-12 (≥11) | Not specified | Prospective | Low |

| Kennedy et al. [83] | UK | Women (42; 60.2) |

Anxiety Depression |

Not specified |

HADS-A (≥11) HADS-D (≥11) |

44.7; not specified | Prospective | Low |

| Kyranou et al. [28] | USA | Women (390; 54.9) |

Anxiety Depression |

Announcement |

STAI (Trait ≥31.8; State ≥32.2) CES-D (≥16) |

Not specified | Cross-sectional | Low |

| Lally et al. [84] | USA | Women (100; 54.2) |

Depression Distress PTSD |

Not specified |

CES-D (≥16) DT (≥4) IES (CT) |

Not specified | Experimental | Low |

| Lee et al. [85] | Korea | Women (111; 44.2) |

Anxiety Depression |

Not specified |

HADS-A (≥8) HADS-D (≥8) |

Not specified | Prospective | Low |

| Linden et al. [27] | Canada | Women and men (2250; 58.9) |

Anxiety Depression |

Not specified | 21-item Psychosocial Screen for Cancer assesses anxiety and depressive symptoms (≥11) | Not specified | Cross-sectional | Moderate |

| Mertz et al. [3] | Denmark | Women (41; 60.0) | Distress | Announcement | DT (≥7) | Not specified | Cross-sectional | Low |

| Miranda et al. [86] | Brazil | Women (20; 49.8) | Depression | Pathological/ clinical | BDI (CT) | Not specified | Cross-sectional | Moderate |

| Ng et al. [87] | Malaysia | Women (211; 55.0) | Distress | Pathological/ clinical | DT (CT) | Not specified | Cross-sectional | Low |

| Oh & Cho [88] | Korea | Women (50; 48.9) |

Anxiety Depression |

Not specified |

HADS-A (≥11) HADS-D (≥11) |

Not specified; 1–3 | Longitudinal | Low |

| Oliveri et al. [89] | Italy | Women (150; 49.0) | PTSD | Pathological/ clinical | PTSD (CT) | Not specified | Prospective | Low |

| Park et al. [90] | USA | Women (54; 35.2) |

Anxiety Depression |

Not specified |

HADS-A (≥11) HADS-D (≥11) |

33; not specified | Cross-sectional | Low |

| Primo et al. [31] | USA | Women (85; 54.8) | PTSD | Not specified | IES (CT) | 11.7; not specified | Prospective | Low |

| Ramalho et al. [91] | Portugal | Women (418; 56.7b) |

Anxiety Depression |

Announcement |

HADS-A (≥11) HADS-D (≥11) |

Not specified | Prospective | Low |

| Romeo et al. [92] | Italy | Women (147; 54.0) | Depression | Announcement | HADS-D (≥8) | Not specified | Longitudinal | Moderate |

| Stafford et al. [93] | Australia | Women (58.9) |

Anxiety Depression |

Announcement |

HADS-A (≥16) CES-D (≥11) |

Not specified | Cross-sectional | Low |

| Tjemsland et al. [32] | Norway | Women (106; 50.9b) | PTSD | Announcement | IES (≥19) | 14; not specified | Cross-sectional | Low |

| Villar et al. [29] | Spain | Women (339; 58.9) | Anxiety | Not specified | STAI (CT) | Not specified | Prospective | Low |

| Voigt et al. [94] | Germany | Women (166; 50.4) | PTSD | Announcement | SCID (CT) | Not specified | Prospective | Low |

| Watson et al. [95] | UK | Women (359; 55.8) |

Anxiety Depression |

Not specified |

HADS-A (≥10) HADS-D (≥8) |

28–84; not specified | Cross-sectional | Moderate |

USA United States of America, UK United Kingdom, PTSD post-traumatic stress disorder, STAI State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, SCID shortened version of the structured clinical interview, HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety/Depression subscale, LSAA/LSAD Leeds general Scales for the self-Assessment of Anxiety/Depression, BSI-18 The Brief Symptom Inventory 18 item, CES-D Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, SCL-90-R Symptom Checklist-90—Revised, PHQ-9 Patient Health Questionnaire 9‐Item, BDI Beck Depression Inventory, SDS The Symptom Distress Scale, POMS Profile of Mood States, DT Distress Thermometer, GHQ-12 General Health Questionnaire-12 items, PC-PTSD 4-item Primary Care PTSD Screen, IES Impact of Event Scale.

aAnnouncement is the diagnosis provided before surgery and pathological/clinical is the definitive diagnosis provided after surgery. All before the medical treatments began.

bMean age calculated by authors since the only percentage by age decade was available.

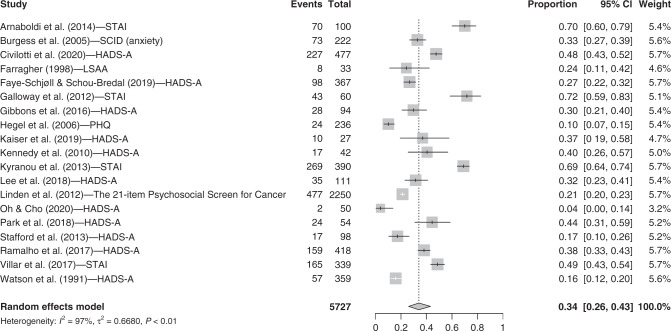

Anxiety symptoms

Nineteen studies were included in the anxiety category. The random-effect model showed that 34.0% (95% CI = [26.0, 43.1]; I2 = 97.1%) of breast cancer patients present clinically significant anxiety symptoms after their diagnosis but before beginning medical treatments (see Fig. 2). Two studies [28, 29] using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory provided the trait and state anxiety scores separately, whereas the majority of studies reported anxiety symptoms using the total score for this tool. To be consistent with the literature, we computed the mean number of clinical cases for the study and used this number in the meta-analysis.

Fig. 2. Forest plot for anxiety symptoms.

Instruments. STAI State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, SCID shortened version of the Structured Clinical Interview, HADS-A Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale- Anxiety subscale, LSAA Leeds General Scales for the Self-Assessment of Anxiety. Other terms. Events: n total of participants with severe anxiety symptoms; Total: n total.

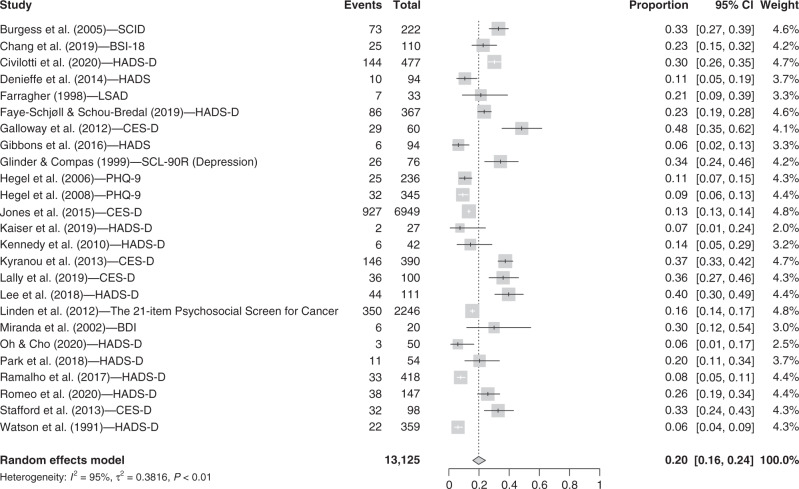

Depressive symptoms

We included 25 studies that reported the prevalence of depressive symptoms in our specified time frame. The random-effect model showed that 19.7% (95% CI = [15.9, 24.3]; I2 = 95.2%) of pre-treatment breast cancer patients present clinically significant depressive symptoms (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Forest plot for depressive symptoms.

Instruments. SCID shortened version of the Structured Clinical Interview, BSI-18 The Brief Symptom Inventory 18 item (depression subscale), HADS-D Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale- Depression subscale, LSAD Leeds general scales for the Self-Assessment of Depression, CES-D Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, SCL-90-R Symptom Checklist-90—Revised (depression subscale), PHQ-9 Patient Health Questionnaire 9‐Item Depression Module, BDI Beck Depression Inventory. Other terms. Events: n total of participants with severe depressive symptoms; Total: n total.

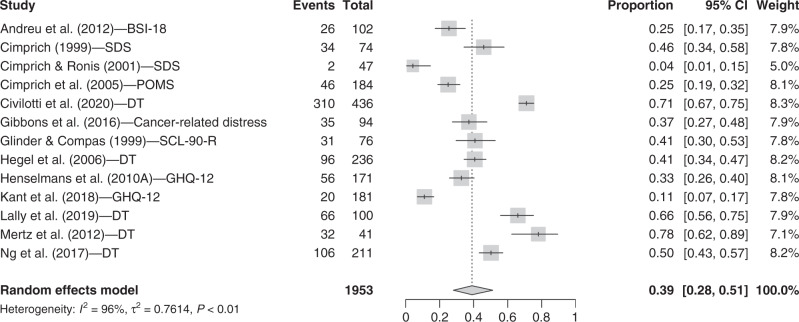

Non-specific distress symptoms

Thirteen studies were included in the non-specific distress category. The random-effect model showed that the prevalence of distress symptoms is 39.0% (95% CI = [28.1, 51.2]; I2 = 95.7%) for breast cancer patients who just received their diagnosis (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Forest plot for non-specific distress symptoms.

Instruments. BSI-18 The Brief Symptom Inventory 18 items (distress), SDS The Symptom Distress Scale, POMS Profile of Mood States, DT distress thermometer, SCL-90-R Symptom Checklist-90—Revised (distress), GHQ-12 General Health Questionnaire-12 items. Other terms. Events: n total of participants with severe non-specific distress symptoms; Total: n total.

Trauma-related symptoms

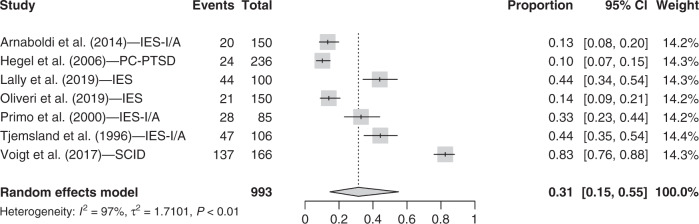

Seven studies were included in the PTSD symptom category. Three studies using the Impact of Event Scale to measure PTSD symptoms provided Intrusion and Avoidance scores separately [30–32], so we computed the mean number of clinical cases for the study and used that number in the meta-analysis. Results from the random-effect model showed that 31.4% (95% CI = [14.6, 55.0]; I2 = 97.3%) of pre-treatment breast cancer patients present clinically significant PTSD symptoms (see Fig. 5). We did not find any study that measured peritraumatic distress symptoms with respect to our inclusion criteria.

Fig. 5. Forest plot for PTSD symptoms.

Instruments. IES-I/A Impact of Event Scale Intrusion and Avoidance scores summed, PC-PTSD 4-item Primary Care PTSD Screen, IES Impact of Event Scale, SCID shortened version of the structured clinical interview. Other terms. Events: n total of participants with PTSD symptoms; Total: n total.

Well-being

Through our article search, seven papers met the inclusion criteria for well-being. However, following data extraction, most of them were either excluded or divided into the symptom categories “anxiety” or “depression,” based on the instrument used. Finally, no studies reporting breast cancer patients’ well-being (e.g., emotional, physical, social and functional well-being) in our specific time frame were found.

Meta-regression analysis

Thirteen studies (excluding the studies that did not disclose the time elapsed since diagnosis) were included in the latter analysis, the meta-regression. We did not find a significant association between time since breast cancer diagnosis and prevalence (P = 0.69).

Discussion

This meta-analysis indicates that high diagnosis-specific distress is manifested in a significant minority of breast cancer patients specifically during the window of time between the diagnosis and the onset of medical treatments and clearly delineates the nature of such symptoms.

Diagnosis-specific distress

The usual stress response to a cancer diagnosis is characterised by shock and denial [33]. Despite efforts to remain focused, patients may have difficulty processing information when faced with this unexpected event. The fact that we found a higher prevalence of non-specific distress (39%) after the diagnosis announcement could indicate that there is a phase during which patients are experiencing shock, distress, uncertainty, and existential and anticipatory anxiety in the face of this new information and its perceived threat. This finding is in line with a literature review that reported a 32.8% prevalence of distress symptoms in breast cancer patients, but some studies included patients who had already started treatment at the time of data collection [34]. Receiving a breast cancer diagnosis changes patients’ views of their future, as they suddenly must consider the possibility of losses, ‘unfinished business’, and death while managing the reactions of their loved ones [35]. These changes to life plans can be accompanied by high levels of distress for many patients [35]. A study that reported the trajectory of distress symptoms in women with breast cancer showed high levels of distress after diagnosis [36]. Psychological distress severity can either decrease over time during the treatment and remission phases [36] or increase continuously after diagnosis, negatively altering the immune system and treatment efficacy [37].

Following the initial shock, anxiety symptoms may develop [33], which can explain the high prevalence of both distress (39%) and anxiety (34%) symptoms in this study. Anxiety is expected in response to receiving a life-threatening diagnosis of cancer. Within 3 weeks following the diagnosis, it becomes easier to discriminate between patients who are having a transient, as opposed to enduring, anxious reaction to the diagnosis [38, 39]. Indeed, research suggests that some breast cancer patients see a decrease of anxiety symptoms as treatment unfolds, but for several others, the symptomatology endures or worsen [40]. Patients with severe anxiety experience many physical symptoms (e.g., vomiting, nausea) that compound cancer-related physical symptoms [39].

In the category of PTSD symptoms, a prevalence of 31% within our specific time frame was found. A recent meta-analysis reported a 9.6% prevalence of PTSD symptoms in breast cancer patients; in that study, participants were mixed, some undergoing treatment and others not [41]. The literature on the prevalence of PTSD symptoms in different cancer phases is rich but lacks consistency since such symptoms are often confused with adjustment reactions [42, 43]. One possible reason for this confusion is the fact that a cancer diagnosis is not always construed as a qualifying event for receiving a PTSD diagnosis according to DSM-5 criteria [43]. Further, the short amount of time between receiving the diagnosis and starting treatment may contribute to the difficulty of diagnosing PTSD during this initial phase, leading clinicians to overlook this diagnosis in favour of other entities, such as a more generic anxiety disorder or an adjustment disorder [43]. There is also a conceptual difficulty in understanding PTSD symptoms during the diagnostic phase in the illness—patients have received their cancer diagnosis, but technically are still undergoing the “trauma” [42]. The Peritraumatic Distress Inventory could be the more appropriate measure to administer while patients are still in the midst of their stressors. Unfortunately, we did not find any study examining the prevalence of peritraumatic distress that met our inclusion criteria. The existing literature suggests that peritraumatic distress is present before undergoing surgery, but this kind of study is clearly missing in oncology [44–46].

According to the Learned Helplessness model, depression often follows anxiety reactions [47]. This model could explain why in our specified time frame, the prevalence of depressive symptoms (19%) was the lowest compared to every other diagnostic-specific distress symptom, especially anxiety. Supporting this theory, trajectory studies show that depression symptoms increase over time and that their prevalence can reach 66.1% during the remission phase [11, 48]. This suggests that depressive symptoms take more time to develop following a breast cancer diagnosis than do distress and anxiety symptoms. Another meta-analysis found a prevalence (32%) seemingly at odds with ours, but that study included patients in the treatment phase [49]. Still, the fact that nearly one in five patients experience clinically severe depressive symptoms makes it a common mental condition among breast cancer patients [12, 13].

We did not find any study falling in the well-being category. First, by using the search term “well-being,” most studies found were actually relying on a broad definition of well-being and measured (the absence of) anxiety or depression. Some studies that examined more specific dimensions of well-being (e.g., optimism, life satisfaction, personal growth) could have been left undetected by the “well-being” search term. Second, because one of the inclusion criteria was to “present the results as the proportion of study participants scoring above the clinical threshold or cut-off scores”, scarce well-being studies could have been included since the vast majority of well-being scales do not have a clinical threshold. Moreover, well-being is assessed more often in the post-treatment/survivorship phase than in the time frame between diagnosis and treatments [50]. However, two promising studies were found using The Emotional Well-Being (EWB) Subscale of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General (FACT-G [51]) to measure patient well-being after receiving a cancer diagnosis but prior to treatments [52]. Sohl et al. [53] showed that well-being was lower prior to radiotherapy than after treatments in breast cancer patients. Positive aspects of well-being during the post-diagnosis phase should be investigated in future research.

Trajectory studies suggest that different symptoms emerge at different time points among cancer survivors according to the phase of the illness they are undergoing: screening, diagnosis, treatments, and remission. Even in a short time frame between diagnosis and treatments, our results support that the prevalence of diagnosis-specific distress symptoms varies according to the distress dimension. After diagnosis, distress symptoms are the most prevalent, closely followed by severe anxiety symptoms; severe depressive symptoms are relatively less common after the diagnosis. Further research is needed to understand the prevalence of PTSD symptoms in the post-diagnosis phase, as well as whether such symptoms are better characterised as peritraumatic distress [54].

Although our results target the psychological consequences associated with receiving the diagnosis of breast cancer per se, it is important to note that some patients experience stress prior to receiving their diagnosis [21]. The screening phase and the anxious anticipation related to possibly receiving a cancer diagnosis are not to be neglected and could also have an impact on the prevalence that we observed. It is also important to emphasise that our results show that the majority of breast cancer patients do not display clinically significant symptoms. The coping strategies and resilience of this group of patients should be recognised and further studied, as this could help develop helpful clinical interventions.

Clinical implications

Currently, in North America, screening for distress symptoms in cancer patients at all stages of the disease is part of the standard of care routine [4]. The high prevalence we found for diagnosis-specific distress symptoms suggests that clinicians should pay more attention to these symptoms as soon as patients receive their breast cancer diagnosis, even if their cancer treatments have not begun. Early screening and treatments for distress could facilitate adherence to breast cancer treatment protocols and increase the quality of life and the chances of survival [4]. This is aligned with our results and with the notion that psychosocial interventions are needed to prevent symptom worsening. A recent meta-analysis showed that cognitive-behavioural stress management interventions (e.g., relaxation training, stress reappraisal, training in interpersonal skills) can reduce stress, serum cortisol, anxiety, depression, avoidance, intrusive thoughts, and negative mood in breast cancer patients undergoing treatments [55]. Such care could be offered to breast cancer patients as an early intervention once the diagnosis is confirmed to reduce distress and prevent escalating symptoms.

Limitations

High heterogeneity

Our results have limitations related to the high heterogeneity found in each symptom category. The heterogeneity varied from 95 to 97%, and it may be accounted for by clinical and methodological factors [56]. Clinical heterogeneity occurs when there are significant differences between participants’ characteristics [56].

In that respect, sociodemographic variables, except for age, were heterogeneous from one study to another. Although we recognise that it is difficult to have a homogenous sample in oncology studies [57], it is important to address these differences to better interpret our results. Some included studies were conducted only on women who received a primary breast cancer diagnosis (e.g., refs. [3, 58]), and others on women diagnosed with either a primary or recurrent breast cancer (e.g., ref. [36]). However, according to Cohen [59], given their poorer prognosis, women with recurrent cancer present more distress symptoms than women with primary cancer, which could lead to greater variability in psychological distress outcomes following diagnosis. In our results, we did not find clear evidence that studies with mixed primary/recurrent samples had higher distress symptom prevalence. In addition, another influential variable was the different stages of breast cancer at the time of diagnosis in our sample: if the cancer is diagnosed at a more advanced stage, the prognosis will be proportionally poorer and the distress may be more severe [60]. In our meta-analysis, not all included studies reported these elements and those that did pool the prevalence for every type of breast cancer diagnosis together.

Second, methodological heterogeneity occurs when the design and protocol differ across studies [57]. The time since receiving a cancer diagnosis in our sample varied from 10 days to a few months. This could impact the severity of symptoms measured as, generally speaking, diagnosis-specific distress symptoms could fade or worsen with elapsed time since the diagnosis was announced [36]. However, we did not find an interaction between time since breast cancer diagnosis and any diagnostic-specific distress symptoms.

The presence of clinical and methodological heterogeneity in our sample shows that there is considerable variability between studies that measure the occurrence of psychological distress-related symptoms during the post-diagnosis and pre-treatment period. We argue that it is crucial to increase standardisation between studies, in conjunction with providing more information about the participants and methods.

Pre-diagnosis background

Another limitation was the studies’ specific methodological limitations that cannot be accounted for by the high heterogeneity. For example, it has been previously shown that not having a family member diagnosed with breast cancer can result in poorer psychological adjustment than having a family history of cancer [35]. The latter case brings about apprehension and mental preparation for that patient, unlike patients who receive a positive diagnosis without a family history. Having a prior mental health condition is also a risk factor for poorer adjustment to cancer [60]. We suggest that studies report these participants’ characteristics in their studies, to better document the symptoms they are measuring, which was not always the case in the studies we reviewed.

Methodology

We limited our data collection to papers written in French or in English. However, ten studies were not included on the basis that they were written in another language. There is a possibility that the inclusion of these studies could have changed our results.

Recommendation for future studies

The methodology is an important parameter impacting the capacity to replicate and compare results across studies. In our sample of studies, the lack of information regarding the time of measurement is a common omission. Future studies should report the time at which symptoms were measured along with the stage of cancer diagnosis and scheduled start of treatment. The methodology implemented by Civilotti et al. [58] serves as a good example.

Many studies did not differentiate between those newly diagnosed breast cancer patients who had and had not started medical treatments. Future studies should more clearly differentiate between those two groups since their symptom profile can be very different.

Psychological distress in cancer research appears to be measured using instruments that are derived from the DSM-5 diagnostic entities. However, these diagnostic entities present a certain degree of overlap. For example, items pertaining to insomnia and cognitive impairments (e.g., difficulty concentrating) can be found in instruments measuring anxiety, depression, distress, and PTSD [61]. Applying the framework suggested by the National Institute of Mental Health’s Research Domain Criteria [RDoC], which proposes to study domains of functioning cutting across diagnostic entities, could help identify the domains that are the most affected in breast cancer patients [61].

Finally, receiving a cancer diagnosis—a life-threatening illness—can be traumatic [17]. Oddly, we did not find any study that measured the presence of trauma-related symptoms in our specific time frame. Many patients develop PTSD symptoms upon learning that they have a cancer diagnosis, but there is much controversy about the proper way to measure these symptoms in the context of cancer [17]. One possible reason for the lack of clarity around cancer-related PTSD could be that previous studies attempted to measure PTSD symptoms too soon after the cancer diagnosis. An alternative would be to measure peritraumatic distress reactions first and PTSD later, as is typically the case in trauma research. Peritraumatic reactions index the subjective response to an event and can help determine whether the event was traumatic or not [16]. Peritraumatic distress symptoms is a robust predictor of who will develop PTSD and could be used for prognosis purposes in cancer research [62].

Receiving a cancer diagnosis can represent a turning point of high magnitude and can elicit psychological symptoms such as anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress and non-specific distress. This meta-analysis aimed to shed light on the nature and occurrence of psychological symptoms in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients who have not yet begun treatment. Our results revealed that such symptoms are clinically severe for approximately one-third of our sample, and develop soon after the diagnosis is announced. Given the implications of diagnosis-specific distress for treatment adherence and prognosis, it should be carefully assessed and addressed before breast cancer treatments begin.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the members of Dr Brunet’s lab (Research Laboratory on Psychological Trauma) and Dr. Marin’s lab (Stress, Trauma, Emotions, Anxiety and Memory [STEAM] lab) for their generous feedback. The authors are thanking Dr. Bernard Fortin, MD, for providing his expertise in oncology. Dr. Marie-France Marin is thanking the Fonds de Recherche en Santé du Québec for a salary award. Finally, the authors thank Connie Guo for linguistic revisions.

Author contributions

JF coordinated the study, carried out all the search and wrote most of the paper. ML assisted JF in all stages of the project, she also reviewed the table of results and wrote some sections of the paper. GE performed the statistical analyses and created the figures and helped with the revisions of the paper. Drs. M-FM and AB provided mentorship at all stages of the study and as the paper was being written and reviewed. Dr. MJC also provided mentorship and precious feedback, especially in the field of breast cancer and mental health. All authors have reviewed this version of the article and agreed to its publication.

Funding information

The authors did not receive funding to conduct the meta-analysis.

Data availability

Data are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This meta-analysis study did not thus involve human participants, human data or human tissue. No ethics approval or contentment to participate were not required.

Consent to publish

This manuscript does not contain any individual person’s data in any form, thus, consent for publication was not required.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41416-021-01542-3.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Sousa Barros AE, Conde CR, Lemos TMR, Kunz JA, da Silva Marques MDL. Feelings experienced by women when receiving the diagnosis of breast cancer. J Nurs UFPE line-Qualis B2. 2018;12:102–11. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mertz BG, Bistrup PE, Johansen C, Dalton SO, Deltour I, Kehlet H, et al. Psychological distress among women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16:439–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holland JC, Andersen B, Breitbart WS, Buchmann LO, Compas B, Deshields TL, et al. Distress management. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2013;11:190–209. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drageset S, Lindstrøm TC, Giske T, Underlid K. “The support I need”: Women’s experiences of social support after having received breast cancer diagnosis and awaiting surgery. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35:E39–E47. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31823634aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epping-Jordan JE, Compas BE, Osowiecki DM, Oppedisano G, Gerhardt C, Primo K, et al. Psychological adjustment in breast cancer: Processes of emotional distress. Health Psychol. 1999;18:315–26. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.4.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landmark BT, Wahl A. Living with newly diagnosed breast cancer: a qualitative study of 10 women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. J Adv Nurs. 2002;40:112–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bower JE. Behavioral symptoms in patients with breast cancer and survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:768–77. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ridner SH. Psychological distress: concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45:536–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang H, Brand JH, Fang F, Chiesa F, Johansson AL, Hall P, et al. Time‐dependent risk of depression, anxiety, and stress‐related disorders in patients with invasive and in situ breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:841–52. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim CC, Devi MK, Ang E. Anxiety in women with breast cancer undergoing treatment: a systematic review. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2011;9:215–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-1609.2011.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maass SW, Roorda C, Berendsen AJ, Verhaak PF, de Bock GH. The prevalence of long-term symptoms of depression and anxiety after breast cancer treatment: a systematic review. Maturitas. 2015;82:100–8. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, Halton M, Grassi L, Johansen C, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:160–74. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fann JR, Thomas-Rich AM, Katon WJ, Cowley D, Pepping M, McGregor BA, et al. Major depression after breast cancer: a review of epidemiology and treatment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:112–26. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Depression and cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1797–810. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brunet A, Weiss DS, Metzler TJ, Best SR, Neylan TC, Rogers C, et al. The peritraumatic distress inventory: a proposed measure of PTSD criterion A2. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1480–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kangas M, Henry JL, Bryant RA. Posttraumatic stress disorder following cancer: a conceptual and empirical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2002;22:499–524. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00118-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong M, Looney E, Michaels J, Palesh O, Koopman C. A preliminary study of peritraumatic dissociation, social support, and coping in relation to posttraumatic stress symptoms for a parent’s cancer. Psycho‐Oncol. 2006;15:1093–8. doi: 10.1002/pon.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leano A, Korman MB, Goldberg L, Ellis J. Are we missing PTSD in our patients with cancer? Part I. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2019;29:141–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnaboldi P, Riva S, Crico C, Pravettoni G. A systematic literature review exploring the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder and the role played by stress and traumatic stress in breast cancer diagnosis and trajectory. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press) 2017;9:473–85. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S111101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Costanzo ES, Ryff CD, Singer BH. Psychosocial adjustment among cancer survivors: findings from a national survey of health and well-being. Health Psychol. 2009;28:147–56. doi: 10.1037/a0013221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ivanauskienė R, Padaiga Ž, Šimoliūnienė R, Smailytė G, Domeikienė A. Well-being of newly diagnosed women with breast cancer: Which factors matter more? Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:519–26. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanson Frost M, Suman VJ, Rummans TA, Dose AM, Taylor M, Novotny P, et al. Physical, psychological and social well‐being of women with breast cancer: the influence of disease phase. Psycho‐Oncol. 2000;9:221–31. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200005/06)9:3<221::aid-pon456>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Welch V, Petticrew M, Petkovic J, Moher D, Waters E, White H, et al. Extending the PRISMA statement to equity-focused systematic reviews (PRISMA-E 2012): explanation and elaboration. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14:1–23. doi: 10.1186/s12939-015-0219-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, March L, Bain C, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:934–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linden W, Vodermaier A, MacKenzie R, Greig D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord. 2012;141:343–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kyranou M, Paul SM, Dunn LB, Puntillo K, Aouizerat BE, Abrams G, et al. Differences in depression, anxiety, and quality of life between women with and without breast pain prior to breast cancer surgery. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17:190–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Villar RR, Fernández SP, Garea CC, Pillado M, Barreiro VB, Martín CG. Quality of life and anxiety in women with breast cancer before and after treatment. Rev Lat-Am Enferm. 2017;25:1–13. doi: 10.1590/1518-8345.2258.2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arnaboldi P, Lucchiari C, Santoro L, Sangalli C, Luini A, Pravettoni G. PTSD symptoms as a consequence of breast cancer diagnosis: clinical implications. SpringerPlus. 2014;3:1–7. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Primo K, Compas BE, Oppedisano G, Howell DC, Epping-Jordan JE, Krag DN. Intrusive thoughts and avoidance in breast cancer: Individual differences and association with psychological distress. Psychol Health. 2000;14:1141–53. doi: 10.1080/08870440008407372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tjemsland L, Søreide JA, Malt UF. Traumatic distress symptoms in early breast cancer I: acute response to diagnosis. Psycho‐Oncol. 1996;5:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holland, JC, Rowland, JH. Handbook of psycho-oncology: psychological care of the patient with cancer. New York: Oxford University Press. 1989.

- 34.Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psycho‐Oncol. 2001;10:19–28. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<19::aid-pon501>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montgomery M, McCrone SH. Psychological distress associated with the diagnostic phase for suspected breast cancer: Systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66:2372–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lam WW, Bonanno GA, Mancini AD, Ho S, Chan M, Hung WK, et al. Trajectories of psychological distress among Chinese women diagnosed with breast cancer. Psycho‐Oncol. 2010;19:1044–51. doi: 10.1002/pon.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Witek-Janusek L, Gabram S, Mathews HL. Psychologic stress, reduced NK cell activity, and cytokine dysregulation in women experiencing diagnostic breast biopsy. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:22–35. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baqutayan SMS. The effect of anxiety on breast cancer patients. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34:119–23. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.101774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stark DPH, House A. Anxiety in cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:1261–7. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woodward V, Webb C. Women’s anxieties surrounding breast disorders: a systematic review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 2001;33:29–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu X, Wang J, Cofie R, Kaminga AC, Liu A. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder among breast cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Iran J Public Health. 2016;45:1533–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cordova MJ, Riba MB, Spiegel D. Post-traumatic stress disorder and cancer. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:330–8. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30014-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kangas M. DSM-5 trauma and stress-related disorders: implications for screening for cancer-related stress. Front Psychiatry. 2013;4:122. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shiban E, Lehmberg J, Hoffmann U, Thiel J, Probst T, Friedl M, et al. Peritraumatic distress fully mediates the relationship between posttraumatic stress symptoms preoperative and three months postoperative in patients undergoing spine surgery. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2018;9:1423824. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2018.1423824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Briere J, Dias CP, Semple RJ, Scott C, Bigras N, Godbout N. Acute stress symptoms in seriously injured patients: Precipitating versus cumulative trauma and the contribution of peritraumatic distress. J Trauma Stress. 2017;30:381–8. doi: 10.1002/jts.22200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cella DF, Cherin EA. Quality of life during and after cancer treatment. Compr Ther. 1988;14:69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Else-Quest NM, LoConte NK, Schiller JH, Hyde JS. Perceived stigma, self-blame, and adjustment among lung, breast and prostate cancer patients. Psychol Health. 2009;24:949–64. doi: 10.1080/08870440802074664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Avis NE, Levine BJ, Case LD, Naftalis EZ, Van Zee KJ. Trajectories of depressive symptoms following breast cancer diagnosis. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomark. 2015;24:1789–95. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pilevarzadeh M, Amirshahi M, Afsargharehbagh R, Rafiemanesh H, Hashemi SM, Balouchi A. Global prevalence of depression among breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;176:519–33. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05271-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mols F, Vingerhoets AJ, Coebergh JW, van de Poll-Franse LV. Quality of life among long-term breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2613–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brucker PS, Yost K, Cashy J, Webster K, Cella D. General population and cancer patient norms for the functional assessment of cancer therapy-general (FACT-G) Eval Health Prof. 2005;28:192–211. doi: 10.1177/0163278705275341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schnur JB, Montgomery GH, Hallquist MN, Goldfarb AB, Silverstein JH, Weltz CR, et al. Anticipatory psychological distress in women scheduled for diagnostic and curative breast cancer surgery. Int J Behav Med. 2008;15:21–8. doi: 10.1007/BF03003070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sohl SJ, Schnur JB, Sucala M, David D, Winkel G, Montgomery GH. Distress and emotional well-being in breast cancer patients prior to radiotherapy: an expectancy-based model. Psychol Health. 2012;27:347–61. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.569714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, Heinssen R, Pine DS, Quinn K, et al. Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:748–51. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tang M, Liu X, Wu Q, Shi Y. The effects of cognitive-behavioral stress management for breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cancer Nurs. 2020;43:222–37. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Song F, Sheldon TA, Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, Jones DR. Methods for exploring heterogeneity in meta-analysis. Ev Health Prof. 2001;24:126–51. doi: 10.1177/016327870102400203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Manne S, Kashy D, Albrecht T, Wong YN, Lederman Flamm A, Benson III AB, et al. Attitudinal barriers to participation in oncology clinical trials: factor analysis and correlates of barriers. Eur J Cancer Care. 2015;24:28–38. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Civilotti C, Maran DA, Santagata F, Varetto A, Stanizzo MR. The use of the Distress Thermometer and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale for screening of anxiety and depression in Italian women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:4997–5004. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05343-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cohen M. Coping and emotional distress in primary and recurrent breast cancer patients. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2002;9:245–51. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thomas BC, Pandey M, Ramdas K, Nair MK. Psychological distress in cancer patients: hypothesis of a distress model. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2002;11:179–85. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200204000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cuthbert BN, Insel TR. Toward the future of psychiatric diagnosis: the seven pillars of RDoC. BMC Med. 2013;11:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bovin MJ, Marx BP. The importance of the peritraumatic experience in defining traumatic stress. Psychol Bull. 2011;137:47. doi: 10.1037/a0021353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. & The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Andreu Y, Galdón MJ, Durá E, Martínez P, Pérez S, Murgui S. A longitudinal study of psychosocial distress in breast cancer: Prevalence and risk factors. Psychol Health. 2012;27:72–87. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2010.542814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arnaboldi P, Lucchiari C, Santoro L, Sangalli C, Luini A, Pravettoni G. PTSD symptoms as a consequence of breast cancer diagnosis: clinical implications. SpringerPlus. 2014;3:392. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Burgess C, Cornelius V, Love S, Graham J, Richards M, Ramirez A. Depression and anxiety in women with early breast cancer: five year observational cohort study. BMJ. 2005;330:702. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38343.670868.D3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chang HA, Barreto N, Davtyan A, Beier E, Cangin MA, Salman J, et al. Depression predicts longitudinal declines in social support among women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Psycho‐Oncol. 2019;28:635–42. doi: 10.1002/pon.5003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cimprich B. Pretreatment symptom distress in women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. 1999;22:185–94. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199906000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cimprich B, Ronis DL. Attention and symptom distress in women with and without breast cancer. Nurs Res. 2001;50:86–94. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200103000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cimprich B, So H, Ronis DL, Trask C. Pre‐treatment factors related to cognitive functioning in women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Psycho‐Oncol. 2005;14:70–8. doi: 10.1002/pon.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Denieffe S, Cowman S, Gooney M. Symptoms, clusters and quality of life prior to surgery for breast cancer. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23:2491–502. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Farragher B. Psychiatric morbidity following the diagnosis and treatment of early breast cancer. Ir J Med Sci. 1998;167:166–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02937931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Faye‐Schjøll HH, Schou-Bredal I. Pessimism predicts anxiety and depression in breast cancer survivors: a 5‐year follow‐up study. Psycho‐Oncol. 2019;28:1314–20. doi: 10.1002/pon.5084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Galloway SK, Baker M, Giglio P, Chin S, Madan A, Malcolm R, et al. Depression and anxiety symptoms relate to distinct components of pain experience among patients with breast cancer. Pain Res Treat. 2012;2012:851276. doi: 10.1155/2012/851276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gibbons A, Groarke A, Sweeney K. Predicting general and cancer-related distress in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:935–43. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2964-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Glinder JG, Compas BE. Self-blame attributions in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer: a prospective study of psychological adjustment. Health Psychol. 1999;18:475–81. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.5.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hegel MT, Moore CP, Collins ED, Kearing S, Gillock KL, Riggs RL, et al. Distress, psychiatric syndromes, and impairment of function in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Cancer. 2006;107:2924–31. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hegel MT, Collins ED, Kearing S, Gillock KL, Moore CP, Ahles TA. Sensitivity and specificity of the distress thermometer for depression in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients. Psycho‐Oncol. 2008;17:556–60. doi: 10.1002/pon.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Henselmans I, Helgeson VS, Seltman H, de Vries J, Sanderman R, Ranchor AV. Identification and prediction of distress trajectories in the first year after a breast cancer diagnosis. Health Psychol. 2010;29:160–8. doi: 10.1037/a0017806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jones SM, LaCroix AZ, Li W, Zaslavsky O, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Weitlauf J, et al. Depression and quality of life before and after breast cancer diagnosis in older women from the Women’s Health Initiative. J Cancer Surviv: Res Pr. 2015;9:620–9. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0438-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kaiser J, Dietrich J, Amiri M, Rüschel I, Akbaba H, Hantke N, et al. Cognitive performance and psychological distress in breast cancer patients at disease onset. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2584. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kant J, Czisch A, Schott S, Siewerdt-Werner D, Birkenfeld F, Keller M. Identifying and predicting distinct distress trajectories following a breast cancer diagnosis-from treatment into early survival. J Psychosom Res. 2018;115:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kennedy F, Harcourt D, Rumsey N, White P. The psychosocial impact of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS): a longitudinal prospective study. Breast. 2010;19:382–7. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lally RM, Bellavia G, Gallo S, Kupzyk K, Helgeson V, Brooks C, et al. Feasibility and acceptance of the caring guidance web‐based, distress self‐management, psychoeducational program initiated within 12 weeks of breast cancer diagnosis. Psycho‐Oncol. 2019;28:888–95. doi: 10.1002/pon.5038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee KM, Jung D, Hwang H, Son KL, Kim TY, Im SA, et al. Pre-treatment anxiety is associated with persistent chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in women treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Psychosom Res. 2018;108:14–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Miranda CRR, De Resende CN, Melo CFE, Costa AL, Friedman H. Depression before and after uterine cervix and breast cancer neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2002;12:773–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2002.01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ng CG, Mohamed S, Kaur K, Sulaiman AH, Zainal NZ, Taib NA, et al. Perceived distress and its association with depression and anxiety in breast cancer patients. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0172975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Oh PJ, Cho JR. Changes in fatigue, psychological distress, and quality of life after chemotherapy in women with breast cancer: a prospective study. Cancer Nurs. 2020;43:E54–E60. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Oliveri S, Arnaboldi P, Pizzoli SFM, Faccio F, Giudice AV, Sangalli C, et al. PTSD symptom clusters associated with short-and long-term adjustment in early diagnosed breast cancer patients. Ecancermedicalscience. 2019;13:917. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2019.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Park EM, Gelber S, Rosenberg SM, Seah DS, Schapira L, Come SE, et al. Anxiety and depression in young women with metastatic breast cancer: a cross-sectional study. Psychosom. 2018;59:251–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2018.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ramalho M, Fontes F, Ruano L, Pereira S, Lunet N. Cognitive impairment in the first year after breast cancer diagnosis: a prospective cohort study. Breast. 2017;32:173–8. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2017.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Romeo A, Di Tella M, Ghiggia A, Tesio V, Torta R, Castelli L. Posttraumatic growth in breast cancer survivors: are depressive symptoms really negative predictors? Psychol Trauma: Theory Res Pr Policy. 2020;12:244–50. doi: 10.1037/tra0000508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Stafford L, Judd F, Gibson P, Komiti A, Mann GB, Quinn M. Screening for depression and anxiety in women with breast and gynaecologic cancer: course and prevalence of morbidity over 12 months. Psycho‐Oncol. 2013;22:2071–8. doi: 10.1002/pon.3253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Voigt V, Neufeld F, Kaste J, Bühner M, Sckopke P, Wuerstlein R, et al. Clinically assessed posttraumatic stress in patients with breast cancer during the first year after diagnosis in the prospective, longitudinal, controlled COGNICARES study. Psycho‐Oncol. 2017;26:74–80. doi: 10.1002/pon.4102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Watson M, Greer S, Rowden L, Gorman C, Robertson B, Bliss JM, et al. Relationships between emotional control, adjustment to cancer and depression and anxiety in breast cancer patients. Psychol Med. 1991;21:51–7. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700014641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request to the corresponding author.