Abstract

Although transcriptome alteration is an essential driver of carcinogenesis, the effects of chromosomal structural alterations on the cancer transcriptome are not yet fully understood. Short-read transcript sequencing has prevented researchers from directly exploring full-length transcripts, forcing them to focus on individual splice sites. Here, we develop a pipeline for Multi-Sample long-read Transcriptome Assembly (MuSTA), which enables construction of a transcriptome from long-read sequence data. Using the constructed transcriptome as a reference, we analyze RNA extracted from 22 clinical breast cancer specimens. We identify a comprehensive set of subtype-specific and differentially used isoforms, which extended our knowledge of isoform regulation to unannotated isoforms including a short form TNS3. We also find that the exon–intron structure of fusion transcripts depends on their genomic context, and we identify double-hop fusion transcripts that are transcribed from complex structural rearrangements. For example, a double-hop fusion results in aberrant expression of an endogenous retroviral gene, ERVFRD-1, which is normally expressed exclusively in placenta and is thought to protect fetus from maternal rejection; expression is elevated in several TCGA samples with ERVFRD-1 fusions. Our analyses provide direct evidence that full-length transcript sequencing of clinical samples can add to our understanding of cancer biology and genomics in general.

Subject terms: Breast cancer, Cancer genomics, RNA sequencing

Namba et al develop a new pipeline called MuSTA to enable the efficient assembly of transcriptome from long-read sequencing data of breast cancer samples. This method enables the authors to discover subtype-specific isoforms, find that fusion transcript structures depend on their genomic context and identify a double-hop fusion that results in aberrant expression of an endogenous retroviral gene.

Introduction

The transcriptome is an important determinant of cellular phenotype1, and changes in the transcriptome are major drivers of oncogenesis and DNA alteration2. In some cases, aberrant splicing regulation is recurrent3 and considered as a driver independent of somatic mutations4. Some genes have cancer-specific splicing isoforms that underlie phenomena related to cancer proliferation, e.g., PKM2 in the Warburg effect5, long non-coding RNA PNUTS in the epithelial–mesenchymal transition6, and BRAF exons 3–9 in chemo-resistance7. Because aberrant splicing is one of the hallmarks of cancer, understanding this phenomenon is indispensable for a better understanding of tumorigenesis.

Several groups recently conducted comprehensive studies of cancer-specific alternative splicing2,8–10 and showed that RNA alteration affects cancer genes in a manner that complements DNA alteration2. However, all of these studies depended on RNA-seq technology, which produces relatively short reads and requires imputation to generate full-length transcripts. Consequently, these analyses were limited to individual splice site abnormalities and could neither directly nor efficiently target consequent transcripts. It is especially difficult to quantify gene expression at the transcript level, and annotation lists based on incomplete sets of isoforms have low estimation accuracy11. Transcript expression exhibits a cell type-specific pattern12, and far more isoforms exist than are registered in the reference annotation13. Therefore, unless we use a complete catalog of transcripts in target cells, it is difficult to correctly evaluate transcript usage.

Complex structural variations (SVs) have been reported in a wide range of cancer types2, but because the scale of SVs is far longer than the length of RNA-seq read fragments, only limited aspects of RNA-seq have been captured through previous analyses. Specifically, in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), a distinct subtype of breast cancer, the genome is heavily affected by SVs due to a deficiency in homologous recombination14–16. However, the characteristics of transcripts derived from genomic regions affected by complex SVs remain to be analyzed.

In this study, we used single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing technology17 to sequence breast cancer clinical specimens in order to directly and comprehensively investigate transcript regulation. SMRT sequencing can obtain far longer reads (≥20 kbp) than short-read sequencing, making it possible to read full-length transcripts without fragmentation (IsoSeq protocol)18. Several groups have used this approach to capture high-resolution transcriptomes of eukaryotes19–21 including human13, many of which revealed transcriptome diversity and previously undescribed transcript regulation22–24. However, this sequencing method has been applied to only a few individual samples. Furthermore, few studies have used it for cancer, especially for clinical cancer specimens25,26. In this study, we constructed a cohort-wide breast cancer transcriptome from directly sequenced transcripts and characterized its complexity and subtype-specific regulation; hundreds of thousands of the isoforms we identified were previously unannotated. We also detected a functional unannotated isoform of TNS3 that was differentially regulated among subtypes. Furthermore, we examined relationships between the exon–intron structure of fusion transcripts and their genomic contexts, and found functional double-hop fusion transcripts transcribed from three distinct genomic regions involved in complex structural alterations. Our findings show that transcript-targeted analyses can directly capture a catalog of cancer isoforms originating from complex structural alterations.

Results

Cohort-wide transcriptome enables more accurate inference of transcript usage

We constructed a cohort-wide transcriptome by merging long-read sequencing of 22 clinical breast cancer specimens. Because long-read consensus sequences are sometimes redundant and distinguished only by sequencing errors, we combined them by focusing on their genomic structures (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1). The transcriptome subsequently went through SQANTI27 filtering, and potential artifact transcripts were removed by a random forest algorithm. We also obtained a number of uniquely associated full-length non-chimeric (FLNC) reads (hereafter referred to as PBcount) in each sample; PBcount serves as a complementary measure of isoform expression. We named this procedure Multi-Sample long-read Transcriptome Assembly (MuSTA) and evaluated its performance using simulation (Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). We also compared the MuSTA-derived transcriptome with the GENCODE reference transcriptome using differential transcript usage (DTU) as the evaluation index, and showed that the former was robust and outperformed the latter in the presence of unannotated isoforms (Fig. 1b–d). DTU is analogous to differential gene expression (DGE), which tells us the variability in the proportion of isoforms at the transcript level. Although current inference methodologies perform poorly in DTU, our results indicated that this might be due to inaccurate annotation at the transcript level, suggesting that direct sequencing of full-length transcriptome could help overcome this limitation and enable us to evaluate transcript usage, even for unannotated isoforms. Comparison of MuSTA with two other pipelines, ToFU18 and FLAIR28, confirmed that MuSTA can accurately construct transcriptomes with less redundancy (Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Figs. 3–6).

Fig. 1. A cohort-wide transcriptome enables more accurate inference of transcript usage.

a Schematic view of the MuSTA workflow. A detailed scheme is depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1. b, c We conducted a simulation based on the full-spliced match (FSM) and novel-in-catalog (NIC) isoforms in the breast cancer data set. As originally described in ref. 27, FSM isoforms are isoforms for which the splice junctions completely match known isoforms, whereas NIC isoforms contain at least one novel splicing junctions but consist of known splicing donors and acceptors. We permutated the log-averaged expression of FSM isoforms and NIC isoforms separately, and randomly set differential gene expression (DGE) and differential transcript usage (DTU). We tested five conditions of NIC ratio against all DTU isoforms (0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 1). Even with a value of 0 (i.e., all DTU transcripts were FSM), we observed higher precision (b) and compatible recall (c) for DTU inference with the MuSTA-derived annotation in comparison with GENCODE. As the NIC rate increased, the MuSTA-derived annotation increasingly outperformed GENCODE, and also exhibited stable precision and recall. The dots represent means, and the error bars represent the standard error of three independent simulations. d Venn diagram of DTU isoforms for a representative simulation with a NIC rate of 0.25. Exp expression, TP true positive, FP false positive, FN false negative.

Cohort-wide transcriptome of 22 breast cancer clinical specimens

We sequenced RNA samples from eight estrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancer and fourteen TNBC clinical specimens, obtaining a total of 6.15 million consensus reads (median 263,378 reads per sample, Supplementary Fig. 7); these were combined into 818,620 non-redundant isoforms. There were 344,504 isoforms that passed SQANTI (hereafter, MuSTA-transcriptome), including 263,711 (76.5%) unannotated isoforms. The median length of the isoforms was 2,936 nt (interquartile range was 2,196). Among them, 344,429 isoforms were mapped to autosomes or chromosome X; of those, 288,674 (83.8%) had multiple exons. The number of isoforms that passed SQANTI in each sample was between 29,246 and 58,756 (median 39,313) (Supplementary Data 1).

We identified 3,081 unannotated multi-exonic genes. Most were detected only in one sample each, but 41 were detected in multiple samples. Ten genes were unannotated in GENCODE v28, which we used throughout this paper, but newly annotated in GENCODE v34. Furthermore, the MuSTA transcriptome contained 17 translated but unannotated open reading frames (uORFs) identified in ref. 29; the authors of that study conducted a CRISPR-based screening to systematically identify ORFs. These results suggested that the MuSTA transcriptome successfully captured isoforms that were actually present but unannotated. In addition, because SQANTI does not acknowledge genomic variants, transcripts with splice sites created by mutation might be deleted as artifacts. Because we could find only seven such isoforms across all the samples, we considered this problem as having a limited effect (Supplementary Data 2).

We observed strong heterogeneity of detected transcripts between samples even within the same subtype, with more than half of the isoforms detected only in one sample (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, the number of detected isoforms decreased as the number of samples sharing the isoforms increased (up to 19 samples), indicating that the majority of isoforms were not ubiquitous. Conversely, when the number of samples sharing the isoforms exceeded 19, the number of isoforms increased (Fig. 2a), suggesting that these isoforms are ubiquitous and essential house-keeping transcripts. Next, to determine whether we had used a sufficient number of samples, we increased the number of analyzed samples one by one and applied MuSTA (Fig. 2b). Although the graph did not reach a plateau, we detected a consistent number of isoforms in more than 80% of samples, indicating that we were able to successfully detect most essential transcripts. However, a larger cohort will be required for the thorough investigation of transcriptome heterogeneity. These data indicated a biphasic distribution of isoforms, with strong heterogeneity of minor isoforms and ubiquitous essential transcripts.

Fig. 2. Isoform distribution detected by MuSTA.

a A histogram of the number of isoforms as a function of the number of samples that generated the isoforms. b The number of detected isoforms when incrementing sample numbers one by one and performing MuSTA. c The number of isoforms for each SQANTI category, which represents the similarity to reference transcripts. FSM full-splice match, ISM incomplete-splice match, NIC novel in catalog, NNIC novel not in catalog. d A heatmap representing the distribution of the number of isoforms from ER-positive and triple-negative subtypes. The groups of isoforms indicated by light blue, blue, purple, and black rectangles were defined as common, ER-specific, TN-specific, and unique, respectively. e The distribution of isoforms according to their categories defined in d. f The number of isoforms restricted to unannotated SQANTI categories. Colored bars represent isoforms predicted to have protein-coding potential. g Bar plot representing the number of subtype-specific isoforms. P-values for the difference in the ratio of protein-coding isoforms are shown (two-sided Fisher’s exact test, Benjamini–Hochberg corrected). h The distribution of maximum transcript per million (TPM) for subtype-specific isoforms. The x axis is shown on a logarithmic scale. i The origins of novel protein sequences predicted to be transcribed from unannotated transcripts. AS alternative splicing, CDS coding sequence, IR intron retention.

We further investigated this heterogeneity with the aid of SQANTI, which classifies isoforms into nine categories by comparison with reference gene annotation: full-splice match (FSM), incomplete-splice match (ISM), novel in catalog (NIC), novel not in catalog (NNIC), genic, genic intron, antisense, intergenic, and fusion. The FSM and ISM categories only contained known splicing junctions. NNIC consisted of isoforms with novel splicing donors or acceptors. NIC isoforms were most abundant, and the pairing of splicing donors and acceptors was much more diverse than what we could find in GENCODE. The second most abundant category was NNIC. Although 80% of those NNIC were detected in only one sample, a certain number of isoforms were recurrently detected. A total of 2765 isoforms were found in all samples; most of these were classified as FSM. On the contrary, almost all isoforms that were classified as genic intron, antisense, intergenic, and fusion were detected only in one sample (Fig. 2c).

Alternatively, we classified the isoforms into four categories from a different point of view: those found in more than half of the samples in both subtypes were defined as “common”; those detected in only one sample were defined as “unique”; isoforms were defined as “subtype-specific” if they were found in only one subtype and the number of detected samples was significantly different between subtypes (P < 0.05) in the two-tailed Fisher’s exact test (i.e., more than three samples in ER-positive breast cancer, and more than seven samples in TNBC); and “other” (Fig. 2d). Although the number of unique isoforms varied according to the total number of isoforms in each sample, there was little variation in the number of common isoforms (Fig. 2e). In each sample, 100–200 isoforms were classified as subtype-specific (Supplementary Data 1).

Repetitive elements in unannotated isoforms

We investigated the repetitive elements in the unannotated isoforms, especially in the intergenic transcripts (Supplementary Notes 3–5 and Supplementary Figs. 8–11). In brief, we took advantage of long-read lengths to successfully map reads containing repetitive sequences using long-read aligners. We detected a substantial proportion of long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs), long terminal repeats (LTRs), and short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs) in intergenic transcripts (Supplementary Figs. 8–10). Intergenic genes were co-expressed with their neighbor genes regardless of the contents of repetitive sequences (Supplementary Fig. 11), suggesting that genes originating from repetitive sequences are also involved in cis-regulation by local genome architecture. We also identified 154 intergenic genes predicted to encode proteins longer than 50 aa, of which 86 were predicted to localize in the nucleus (Supplementary Note 4).

Unannotated isoforms as a rich resource of cancer-specific neo-junctions

We also evaluated the protein-coding potential of unannotated isoforms (Fig. 2f). NIC isoforms included large numbers of predicted protein-coding isoforms, but surprisingly, the NNIC isoforms had the largest proportion of isoforms with protein-coding potential. This may be explained by the fact that the NIC isoforms included unspliced (or intron retention) isoforms, which might contain premature stop codons. The protein-coding potential was higher in TN-specific isoforms than ER-specific isoforms in the NNIC and intergenic categories (Fig. 2g). The caveat is that the TN-specific isoforms tended to be expressed at higher levels, as the larger number of TNBC samples resulted in more stringent criteria for subtype specificity (Fig. 2h), potentially confounding the protein-coding potential of the subtype-specific isoforms.

We noticed that a substantial fraction of predicted protein sequences encoded by unannotated isoforms were not registered in databases (Fig. 2i). These isoforms were 2.15 times more abundant in NNIC than in NIC, despite the smaller number of isoforms with protein-coding potential in NNIC. The NNIC transcripts, by definition, had at least one novel splice junction, and therefore tended to encode novel protein sequences. Importantly, 4.1% of these peptide sequences were derived from “neo-junctions”, which were reported as tumor-specific splice junctions in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) cohort; these sequences are thought to bind MHC-I and act as neo-antigens10.

Thus, we identified a large number of potential protein-coding sequences that had not been previously recorded, including a substantial number of alternative splicing events that may produce neo-antigens.

Subtype-specific isoforms reflect relationships between cancer genes and subtypes

We hypothesized that subtype-specific isoforms encode key molecules involved in cellular pathways specific to the corresponding subtypes. To address this, we selected the top 100 subtype-specific isoforms with the highest fold change in transcripts per million (TPM) (Fig. 3a). Isoforms from key oncogenes in the ER-positive subtype, such as the ESR1 and PGR isoforms, were present in the top 100 isoforms. Figure 3a shows NIC isoforms from subtype-specific genes, including an AGR3 isoform in ER-positive breast cancer30 and a GABRP isoform in TNBC31. Among the NNIC isoforms, KLK5 is a tumor suppressor gene (TSG)32 and LOXL4 is involved in breast cancer metastasis33; moreover, four isoforms of these genes were among the top 100 subtype-specific isoforms. It is likely that the number of subtype-specific isoforms reflected the association of genes with the respective subtypes. In reality, ESR1 had the largest number of subtype-specific isoforms in ER-positive breast cancer (Fig. 3b). GABRP had the largest number of subtype-specific isoforms in TNBC, and other oncogenes such as BCL11A and PABPC1 also had many TNBC-specific isoforms. The results of this analysis may lead to the identification of novel oncogenes associated with breast cancer. For example, 17 isoforms of unknown origin (novel genes) were among the top 100 isoforms, and these warrant further investigation.

Fig. 3. Subtype-specific isoforms reflect relationships between cancer genes and subtypes.

a The top 100 subtype-specific isoforms with the highest fold changes in transcript per million (TPM). Log-transformed PBcount data in each sample are indicated in the heatmap. Subtype and BRCAness are annotated for samples (top), and isoform classification by SQANTI and log2 TPM fold change are annotated for isoforms (right). Absolute values of log2 fold change greater than 10 were truncated. b, c Circular plots indicating the number of isoforms according to isoform categories defined in Fig. 2d and differential transcript usage (DTU). b ER-specific. c TN-specific. Gene symbols of oncogenes are colored in blue. The three numbers below each gene symbol indicate the numbers of specific (left), non-unique (center), and all (right) isoforms.

To validate the existence of isoforms detected in MuSTA, we focused on SOX9-AS1, a long non-coding RNA on the antisense strand of the transcription factor gene SOX9. In our data, two isoforms were expressed strongly in TNBC (Fig. 3a), and 42 isoforms including four TNBC-specific isoforms were detected (Fig. 3b). We also detected readthrough transcripts spanning SOX9-AS1 and its adjacent gene, AC005152.3. Using nested PCR, we validated the existence of these isoforms (Supplementary Fig. 12).

Differential transcript usage analysis with MuSTA-transcriptome captured previously reported isoform switching

As another approach to capture subtype-related isoforms, we conducted DTU tests with the transcriptome obtained by MuSTA, assuming that those genes have functional relevance to breast cancer biology. We detected 465 DTU genes (FDR < 0.01), including 46 cancer-related genes and 10 genes specifically related to breast cancer, including ESR1 and BCL11A (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Figs. 13a–c).

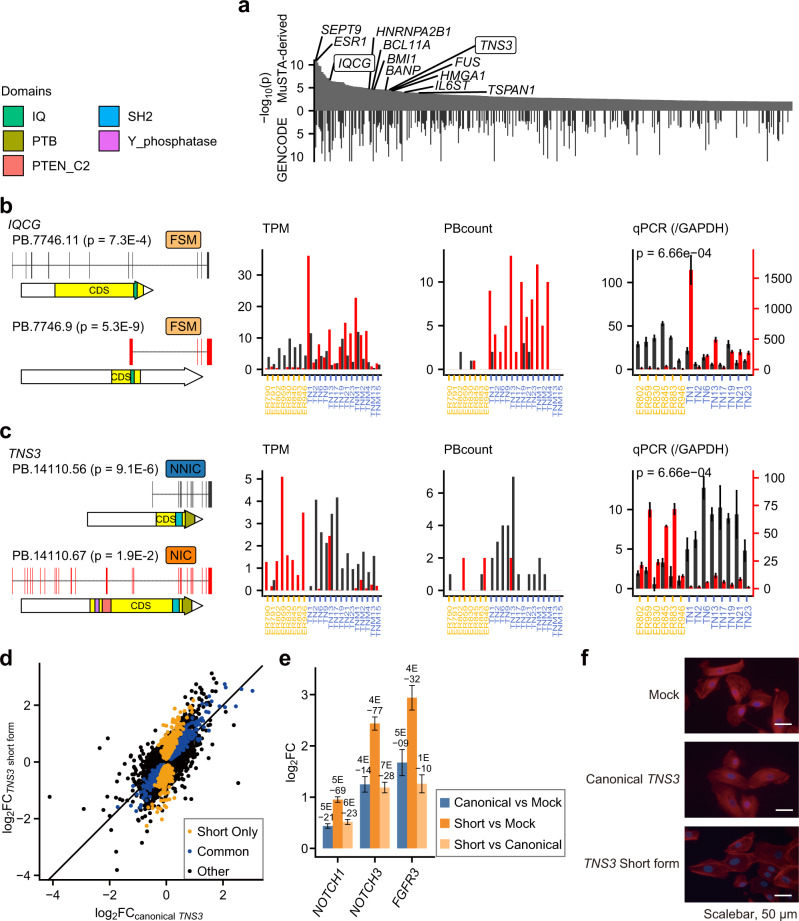

Fig. 4. Differential transcript usage in the MuSTA transcriptome.

a −Log10 P-value of differential transcript usage (DTU) inference in isoforms with P < 0.01 when using the MuSTA transcriptome. P-values were corrected in a stage-wise manner described in ref. 56. −log10 P-values for GENCODE annotation are shown for isoforms that are annotated in GENCODE. We sorted genes in the ascending order of DTU P-values corresponding to the MuSTA transcriptome. The gene symbols with the smallest P-values are labeled according to whether they are oncogenes or TSGs. Two genes were validated by qRT-PCR, and are labeled with boxes. b, c qRT-PCR validation of IQCG (b) and TNS3 (c). Shown are SQANTI classifications, transcript structures, predicted protein domains of two DTU isoforms with the smallest P-values, and expression of DTU isoforms. Three types of expression data are shown [transcript per million (TPM) aligned to the MuSTA transcriptome, PBcount, and relative qPCR expression against GAPDH]. Relative qPCR expression has two y-axes along with DTU isoforms, because qPCR was conducted separately for each isoform. Error bars in the qPCR graphs indicate the standard deviation of three replicates. P-values for relative expression of DTU isoforms were calculated by a two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test. d Log2 fold changes of gene expression in TNS3-expressing MCF10A cells against MCF10A cells transduced with mock vector. The definitions of “short only” and “common” genes are visualized in Supplementary Fig. 14d. e Log2 fold changes of NOTCH1, NOTCH3, and FGFR3 expression between MCF10A cells expressing TNS3 short form, canonical TNS3, and mock vector. Error bars represent the standard error. f MCF10A cells, into which viral vectors were introduced, were stained with Alexa Fluor 594-labeled phalloidin to visualize actin organization. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258.

Among DTU genes, MED24 has canonical and short isoforms; the former is expressed ubiquitously, whereas expression of the latter is specific to a highly metastatic mouse breast cancer cell line (4T1)34. We confirmed the ubiquitous expression of the canonical isoform and found that the short isoform was selectively suppressed in TNBC (Supplementary Fig. 14a), but we failed to replicate this finding by PCR. However, the isoform expression in mouse was validated by PCR in the original article. The differences in our PCR results might be due to the difficulty of designing PCR primers for MED24, as all of the exons of MED24 short isoform are present in the long isoform. Given that the 4T1 cell line is a triple-negative cell line, escape from the regulation of short-form MED24 might be associated with metastasis.

Another DTU gene, TPD52, which has a short isoform encoding PrLZ, is a biomarker of prostate cancer and has an anti-apoptotic function35,36. This isoform exhibits androgen-dependent expression in prostate cancer37. We observed expression of the short isoform specific to ER-positive cancers through our analysis (Supplementary Fig. 14b).

IQCG intronic TSS induces the overexpression of exons 9–12, and Bjørklund et al. pointed out that deregulated expression in this region might be oncogenic38. Using MuSTA and an additional RT-qPCR experiment, we confirmed that PB.7746.9 (matched to ENST00000478903.5) was overrepresented relative to other isoforms in TNBC, and that this matched the reported intronic-start transcript (Fig. 4b). Based on these findings, we conclude that MuSTA successfully captured known isoform-switching events.

Next, we conducted Gene Ontology and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis for the DGE and DTU genes (Supplementary Fig. 13d, e). In DGE genes, pathways related to peptidase processing, ectodermal development, and the cell cycle were enriched. Curiously, eight out of the top ten biological processes enriched in DTU genes were associated with molecular binding. mRNA metabolic process, cell division, and RNA processing were among the molecular functions enriched in DTU genes. The two significantly enriched KEGG pathways were the spliceosome and the cell cycle. Therefore, isoform switching is implicated in the regulation of the cell cycle and RNA processing. Notably, although DTU genes (and in particular, DTU isoforms) were not identical between the MuSTA and GENCODE transcriptomes, these findings remained true (Supplementary Fig. 13f, g).

The short form of TNS3 has a different function from canonical TNS3

Given the recapitulation of known isoform switching by MuSTA, we focused on a DTU event of TNS3 (Tensin3), which included an unannotated short NNIC isoform (PB.14110.56) (Fig. 4c). Tensin3, a protein with an SH2 domain and a C2 domain, contributes to cell migration, anchorage-independent growth, and metastasis in several types of cancer, including breast cancer39–41. Although the functional differences in TNS3 isoforms have not been extensively studied, several single-nucleotide polymorphisms in 7p12.3 have been reported as pleiotropic cancer susceptibility loci42 and coincide with splicing quantitative trait loci (sQTLs) of TNS343, suggesting that alternative transcription of TNS3 plays an important role in cancer.

The TNS3 short form had an unannotated first exon whose genomic sequence is conserved among vertebrates. In addition, this first exon was associated with peaks of chromatin modifications associated with promoter or enhancer elements in TNBC cell lines and normal breast epithelial cells, whereas these peaks were not observed in ER-positive cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 14c). These findings support the existence of the unannotated isoform and suggest that it is under epigenetic control.

To investigate the function of the TNS3 short form, we conducted RNA-seq and analyzed the gene expression profiles of MCF10A immortalized mammary epithelial cells into which viral vectors expressing canonical TNS3 or the TNS3 short form had been introduced. DGE analysis revealed that the TNS3 short form had an impact on gene expression similar to that of canonical TNS3, but with larger effect sizes (Fig. 4d, e and Supplementary Data 3). In addition, more genes (881) were affected specifically by the TNS3 short form (Supplementary Fig. 14d). Gene Ontology analysis suggested that TNS3 altered several features related to cellular adhesion, and that the TNS3 short form had a larger impact than canonical TNS3 (Supplementary Fig. 14e, f). “Regulation of extracellular matrix” was one of the gene ontologies enriched in cells expressing short-form TNS3, suggesting its association with metastasis. The formation of actin filament stress fibers was indeed enhanced in cells expressing the TNS3 short form (Fig. 4f). We also found that expression of NOTCH1, NOTCH3, and FGFR3, important drivers of TNBC, was higher in MCF10A cells expressing the TNS3 short form (Fig. 4e). Together, these data showed that the TNS3 short form has a function distinct from that of canonical TNS3, and may drive tumor initiation or progression. We also noticed that expression of the TNS3 short form, but not that of canonical TNS3, in MCF10A cells was induced by TGFβ (Supplementary Fig. 14e). These observations strongly indicated that isoform switching of TNS3 has important functional implication for cancer cell phenotype, although further investigation is required to delineate the functional significance and mechanistic basis.

Next, we verified the expression of the TNS3 short form in TCGA by calculating percent-spliced-in (PSI) of its first intron. We confirmed that PSI was higher in basal breast cancer than luminal A or luminal B breast cancer; surprisingly, high PSI was also observed in a broad range of cancer types, specifically in glioblastoma multiforme, brain lower-grade glioma, and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (Supplementary Fig. 15). To examine the association of the TNS3 short form with prognosis, we conducted regression analyses under Cox proportional hazards models (Supplementary Data 4 and “Methods” section). Higher PSI was associated with significantly worse prognosis for OS, DSS, and DFI in kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted FDR < 0.05) and for OS and DSS in stomach adenocarcinoma. Nominal significance (unadjusted P < 0.05) was observed for OS of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; DSS of lung adenocarcinoma; DFI of lung squamous cell carcinoma; and PFI of glioblastoma multiforme, stomach adenocarcinoma, bladder urothelial carcinoma, and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. On the other hand, the association was not significant for breast cancer. This might be because the effect of TNS3 was canceled out by the dependence of the TNS3 isoform switch on the breast cancer subtype. Therefore, we restricted the analysis to the basal subtype and observed a hazard ratio greater than one, although it was not significant, probably due to the small sample size (n = 148). Overall, these data indicated that the TNS3 short isoform was associated with poor prognosis in a wide range of cancer types, although confirmation of this association will require additional investigation in a larger cohort.

Structure of fusion transcripts reflects the genomic context

Although short-read sequencing makes it possible to detect the breakpoints of structural variation with high sensitivity and accuracy, long-read sequencing enables us to see the structure of resultant transcripts accurately to an extent that could not be achieved with short-read sequencing.

Of the chimeric IsoSeq cluster reads found in nine TNBC samples, we identified 402 reads with corresponding breakpoints in whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data (Supplementary Fig. 16a). When the transcript fragments 5′ and 3′ of the fusion points were multi-exonic, almost all were mapped to genic regions. By contrast, when they were mono-exonic, more than half were mapped onto non-genic regions (intergenic, genic intron, or antisense regions) (Fig. 5a, b). Almost all transcript fragments containing TSSs were mapped to genic regions, versus only half of the downstream fragments, suggesting that transcriptional initiation has a stringent requirement for a known TSS.

Fig. 5. Transcript structure of fusion transcripts.

a Schematic of gene fragments. b Distribution of the number of exons per gene fragments according to their genomic regions and order in fusion transcripts. c Bar plots showing the number of fusion-specific splicing junctions for each order of gene fragments in fusion transcripts. d Motif of fusion-specific splicing junctions. Note that the first two intronic bases were intentionally chosen. e A heatmap with axes representing exon–intron structures at both edges of fusion points. Colors and numbers indicate the proportions of confirmed canonical splice sites at fusion points. “Non-genic” means that the corresponding gene fragments were mapped to an intergenic, genic intron, or antisense regions. “Intronic/downstream” means that a fusion point is on an intron or downstream of genes. “Alt-exonic” means an alternative exon, and “cons-exonic” means a constitutive exon.

Next, in order to characterize the aberrant transcription caused by chromosomal rearrangement, we examined fusion-specific splicing junctions. We defined fusion-specific splicing junctions as splicing junctions that exist on neither GENCODE transcripts nor non-chimeric MuSTA isoforms. Most of them were located 3′ of the fusion points (Fig. 5c). A total of 49 (68%) fusion-specific splice junctions were found in non-genic regions, whereas others were detected in genic regions. The motif of fusion-specific splicing junctions was similar to that of ordinary canonical junctions (Fig. 5d), with the caveat that the first two intronic bases were intentionally chosen because we removed chimeric reads with non-canonical junctions (other than GT-AG, GC-AG, and AT-AC) that were not detected in the GENCODE or MuSTA transcriptome.

Next, we examined the genomic DNA sequences of fusion points in association with the fusion-specific splice junction. When we sorted reads according to genomic contexts of fusion points (Fig. 5e), the 5′ ends of fusion points were found mostly within introns or downstream of the genes to which the fusion transcript fragments were assigned. When both sides of genomic DNA fusion points were located at introns or downstream of genes, transcribed and spliced sequences matched the canonical splicing motif in all cases (75/75), indicating that novel exons or splice junctions concordant with splicing rules were indeed generated in association with chromosomal rearrangements. In addition, there were a few reads that matched the splicing motif even when the 5′ ends or 3′ ends of the fusion points were on constitutive exons. Thus, it is reasonable to speculate that the exon–intron structures in these reads changed based on structural context.

Double-hop fusion transcripts originated from complex genomic structural variations

The concordance of splicing rules in fusion transcripts raised further questions. Do complex structural variations (SV) produce transcripts that undergo splicing regulation? Are they functional, possibly even acting as oncogenic drivers? In recent years, long-read genomic sequencing has been used to identify complex SVs that were impossible to detect with next-generation sequencing44,45; however, these questions are yet to be answered. Of the chimeric IsoSeq reads, we have identified five non-redundant reads that were mapped to three regions and had breakpoints that were detected in WGS data (Fig. 6a, b and Supplementary Figs. 16b, c, Supplementary Data 5). We have confirmed the fusion transcripts of HIST1H2AG–NonGenic–ERVFRD-1, OGG1–NonGenic–NonGenic, and SLC12A2–NonGenic–SLC12A2 by Sanger sequencing of PCR amplicons. Note that two fusion reads, HIST1H2AG–NonGenic–ERVFRD-1 and SMIM13–NonGenic–NonGenic, were transcribed from the sense and antisense strands of the same rearranged locus, although we could not PCR-amplify the latter fusion transcript. Very recently, the Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes consortium found several bridged fusion transcripts that mapped to two genomic regions connected by a non-transcribed genomic fragment2. However, the double-hop fusions we found had internal genomic regions of thousands of base pairs, and some fusions were even spliced in these regions (Fig. 6a). This type of fusion transcripts cannot be found without long-read transcriptome sequencing.

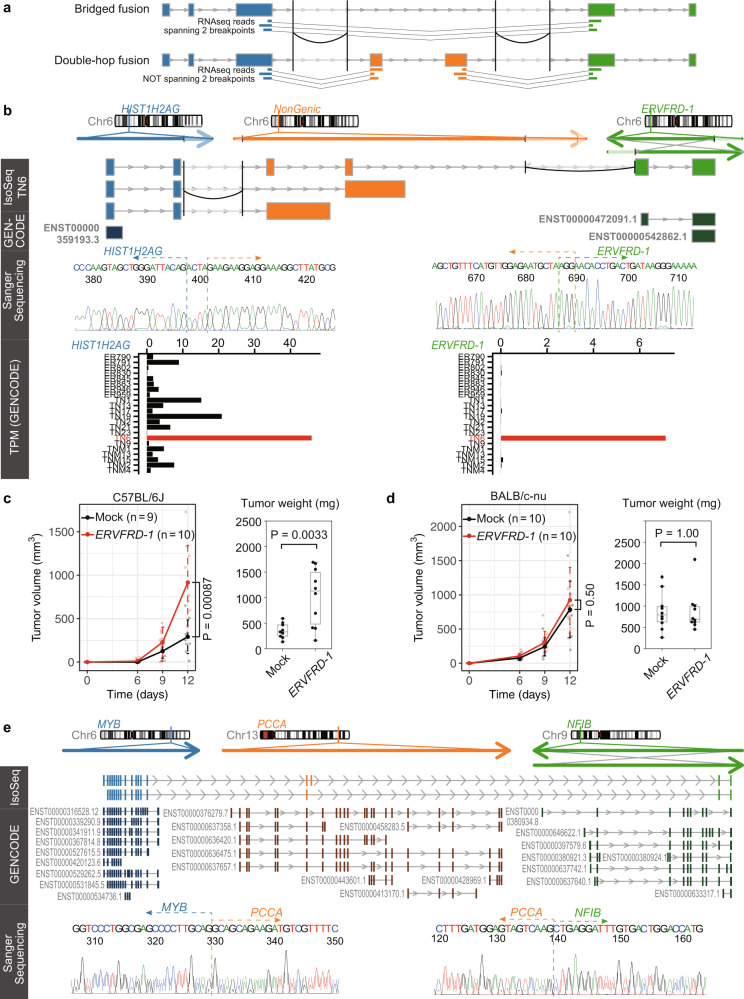

Fig. 6. Double-hop fusion.

a Schematic image of difference between bridged fusion transcript and double-hop fusion transcript. b Structure of double-hop fusion transcripts from HIST1H2AG–NonGenic–ERVFRD-1. The genomic axes represent three original genomic regions; below them are chimeric IsoSeq cluster reads. Curves correspond to structural variants detected with whole-genome sequencing data. The category “GENCODE” shows annotated transcripts. Outside regions of structural variants are shaded. To ensure visibility, exon–intron structures do not necessarily reflect accurate length. TPM denotes transcript per million. c, d Growth of MC38 tumor cells expressing ERVFRD-1 in C57BL/6J mice (c) and in BALBc/nu-nu mice (d). Error bars represent standard error. e Structure of double-hop fusion transcripts from MYB–PCCA–NFIB. Representative transcripts are shown for the GENCODE transcriptome.

Because HIST1H2AG–NonGenic–ERVFRD-1 contains the full CDS of ERVFRD-1, full-length ERVFRD-1 protein might be translated from the fusion transcript. ERVFRD-1 was specifically expressed in samples carrying the fusion transcript. Expression of ERVFRD-1 is generally suppressed across all tissues, except in the placenta43. Furthermore, considering the chromatin modification status, it is quite possible that this double-hop fusion transcript utilized the cis-regulatory region of HIST1H2AG observed in one normal breast epithelial cell line and two breast cancer cell lines (Supplementary Figs. 17a–c), suggesting the existence of a mechanism similar to enhancer hijacking46. The most important difference between this case and enhancer hijacking is that the promoter and enhancer region of HIST1H2AG was located 50 kb upstream of ERVFRD-1 even in a rearranged chromosome, and HIST1H2AG–NonGenic–ERVFRD-1 used the region by forming the readthrough transcript that spanned two breakpoints.

We also noticed that ERVFRD-1 was highly expressed in four samples from TCGA that carry ERVFRD-1 fusions (ABHD12–ERVFRD-1, ELOVL2–ERVFRD-1, NEDD9–ERVFRD-1, and NOL7–ERVFRD-1, respectively, according to FusionGBD47) (Supplementary Fig. 17d). Because ERVFRD-1 inhibits antitumor immunity in an allogeneic mouse tumor model48, we measured the growth of tumor cells expressing ERVFRD-1 in a syngeneic mouse model using MC38 murine colon cancer cells derived from a C57BL/6J mouse. MC38 cells expressing ERVFRD-1 generated larger tumors in C57BL/6J mice than control MC38 cells infected with empty vector (Fig. 6c). By contrast, MC38 cells expressing ERVFRD-1 and control MC38 cells formed tumors of similar sizes in BALBc/nu-nu mice (Fig. 6d). Similar results were obtained using the murine mammary carcinoma cell line EMT6, although the results were marginally significant (Supplementary Fig. 18). These results indicated that ERVFRD-1 promoted tumor growth by inhibiting the antitumor immune response of the host mice, and that enhanced expression of ERVFRD-1 in human cancer cells might contribute to the growth of tumors as well.

The identification of functional double-hop fusion genes prompted us to search for other examples. In a literature search, we noticed that adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) occasionally carries cryptic MYB–NFIB fusion genes in which an intervening sequence is inserted between the MYB and NFIB transcript fragments, although the genomic configurations of the cryptic fusion genes were not determined49. Coincidentally, we identified double-hop fusion gene MYB–PCCA–NFIB among ACC tumors, which we are now investigating in another project independent of this study. To confirm the existence of the fusion gene, the entire coding sequence of the fusion gene was amplified by PCR. By cloning the PCR amplicons, we identified two variants of the fusion genes (Fig. 6e). One of them (the lower variant in the figure) was an in-frame fusion, suggesting that it was a driver fusion event. Although we did not determine the genomic configuration of the fusion gene, it was very likely that the fusion gene was transcribed from three parts of the rearranged genome, as there were at least two splicing variants corresponding to the PCCA transcript, and one of the variants was spliced within the PCCA locus. Thus, we identified another example of a double-hop fusion gene.

Discussion

Here, we have described the diversity and heterogeneity of breast cancer transcripts at both the inter-subtype and intra-subtype levels. The transcriptome we determined allowed us to conduct comprehensive analyses of subtype specificity and DTU using isoforms expressed in target sample groups. These analyses recapitulated known transcript-level regulation of cancer-related genes and also revealed an unannotated isoform of TNS3 as a novel driver of breast cancer.

TNS3 is known for its contribution to metastasis; its SH2 and C2 domains promote cell migration and metastasis by binding other molecules in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signal transduction pathway39–41. Epidermal growth factors simultaneously regulate TNS3 and TNS4, also known as C-terminal tensin-like protein (CTEN), to promote mammary cell migration41. Although further investigation is required to obtain mechanistic insights, it is clear that the protein encoded by the TNS3 short form lacks the N-terminal C2 domain and a structure similar to that of CTEN, which might result in functional differences between the TNS3 short form and canonical TNS3.

Furthermore, we used the full-length sequencing capability of IsoSeq to reveal several features of the exon–intron structures of fusion transcripts and fusion-specific splice sites. In addition, we detected double-hop fusion transcripts. Double-hop fusions can be detected by RNA-seq if their central exons are small enough. A few studies have reported sporadic cases50–52. Our discovery and PCR validation of multiple double-hop fusions that underwent canonical splicing establishes the concept of double-hop fusions and indicates that they are prevalent in cancer. The putative driver fusion (MYB–PCCA–NFIB) and the enhancer hijacking-like mechanism (HIST1H2AG–NonGenic–ERVFRD-1) shed new light on the role of complex SVs and splicing in cancer transcriptomics. We believe that further research will reveal unknown functions of double-hop fusions, giving us insights into new mechanisms of tumorigenesis.

To summarize, full-length transcript sequencing in multiple samples provides a transcript-level analysis that complements conventional RNA-seq approaches, enabling us to focus on isoforms from target cells and apply pre-existing analytical methods such as clustering, DGE, DTU, and Gene Ontology analysis. In addition to long-read RNA sequencing data, MuSTA requires reference genomic sequence and transcriptome data as mandatory inputs; these are available for human and several other species. There are two major long-read sequencing techniques, SMRT sequencing from Pacific Biosciences and nanopore sequencing from Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT). Although we used SMRT sequencing reads in this paper, MuSTA could theoretically be applied to ONT reads as well.

Our methods have the potential for a variety of uses. In light of the emerging evidence that gene isoforms are responsible for cancer survival53 and drug response54, elucidating cancer profiles at the isoform level might provide further druggable targets or previously undiscovered biomarkers. In future work, we will investigate cancer-specific isoforms as sources of neo-antigens. Beyond cancer, there is increasing evidence that variant-induced splice alteration leads to a wide range of diseases such as autoimmune and neurological disorders. With a larger cohort, it might be possible to perform QTL analysis at the isoform level; we predict that such an approach would have a more direct impact on the study of gene functions than sQTLs.

Our analysis had several limitations. First, the most important limitation was the lack of sufficient sample numbers to detect isoforms expressed at low levels. Also, because it is difficult to efficiently amplify long (>6 kb) transcripts, long transcripts might be only partially read. Currently, technologies for long-read sequencing are developing rapidly. For example, according to Pacific Biosciences, the newly developed Sequel II generates at least 8-fold more data and far longer raw reads than the conventional Sequel, (https://www.pacb.com/blog/award-winning-sequel-ii-system). The advance of SMRT sequencing will improve the comprehensiveness of isoform detection, and transcript-level expression analysis can be expected to increase in accuracy. Second, although we mainly targeted the isoforms shared across several samples, each sample contained a substantial number of unique isoforms that deserve further evaluation. These isoforms may reflect sample-specific states including somatic mutation and epigenetic alteration55, or may simply be the result of aberrant splicing coupled with an elevation of gene expression. Third, our procedure was not fully annotation-free because we used SQANTI filtering, although this approach provides a cohort-wide transcriptome that contains a large number of unannotated isoforms.

Despite these limitations, our findings revealed functional unannotated isoforms that contribute to carcinogenesis. In this report, we have shown that cohort-wide full-length transcriptome sequencing is a unique and useful tool, unveiling complex aspects of gene regulation in the cancer transcriptome that could not be directly evaluated by short-read RNA-seq. Hence, we believe that the approach described here will play an essential role in advancing cancer biology.

Methods

Tumor samples

Surgically resected breast tumors were obtained from patients treated at the Yamaguchi University and Mie University Hospital. The patients gave informed consent prior to their participation in the study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Cancer Center Research Institute (#2015-202).

Reference genome and annotation files

We used hg38 as the reference genome and the GENCODE version 28 comprehensive gene annotation as the annotation file, unless otherwise noted. We focused on isoforms mapped to autosome or chromosome X after we applied our pipeline.

Definition of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes (TSGs)

We defined oncogenes as those identified in at least one of three curated oncogene databases: Cancer Gene Census57 (version 90), ONGene58, and OncoKB59 (version 1.23). Because ONGene collected only oncogenes, we used the other two repositories for TSGs.

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS)

WGS was conducted as described previously15. The original data are publicly available (https://humandbs.biosciencedbc.jp/en/hum0094-v3#WGS). In this study, we re-analyzed the data as follows. We detected mutations and structural variants (SV) in two ways and combined them together. First, as shown in our previous research15, we used in-house pipeline for analysis. Because we worked with hg19 for our pipeline, the results were transferred to hg38 using the liftover tool. Next, to detect short structural variants (SVs), we used Genomon60, an analytic pipeline for next-generation sequencing data, which carries out mapping using STAR61, annotation, and additional functions including detection of SVs for DNA and intron retention for RNA.

RNA-seq

Transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) was conducted as reported previously15. The original data are publicly available (https://humandbs.biosciencedbc.jp/en/hum0094-v3#RNA-seq). RNA-seq was performed with 100 bp paired-end reads using the NEBNext Ultra Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). In this study, we re-analyzed the data as follows. RNA-seq reads were mapped to the hg38 reference assembly, and expression data were calculated as transcripts per million (TPM) in two ways: by the quasi-mapping-based mode of Salmon62 and the STAR-RSEM protocol61,63. The Salmon index was used with the ‘–keepDuplicates’ option, and Salmon quant was performed with ‘-l A –gcBias –seqBias –validateMappings’ options. RSEM was performed with the following commands:

rsem-prepare-reference –gtf –star

rsem-calculate-expression –star –paired-end <short-1.fastq><short-2.fastq>

We detected splice junctions and intron retention using Genomon, which ran STAR internally for mapping to the reference genome.

For the Annotation file, we used GENCODE version 28 or a set of transcripts retrieved from our SMRT analysis pipeline.

BRCAness

We defined the triple-negative breast cancers with defective homologous recombination (BRCAness) based on profiles of structural variations, mutational signatures, germline mutational status of BRCA1, expression of BRCA1 and RAD51C, and promoter methylation of BRCA1 and RAD51C as described previously15.

SMRT sequencing

Long-read sequencing was performed using the Pacific Biosciences Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing technology with SMRT cell chemistry (SMRTbell Template Prep Kit 1.0, Sequel Binding Kit 2.0, Sequel Sequencing Kit 2.0, all from Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA). Full-length cDNA libraries were constructed from 1 µg of total RNA using the SMARTer cDNA synthesis kit (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan), utilizing the switching mechanism at the 5′ end of RNA template (SMART) technology coupled with PCR amplification. PCR amplification was performed with PrimeSTAR GXL DNA Polymerase (Takara Bio). The sequencing templates used for SMRT sequencing on the Sequel platform (SMRTbell) were constructed from 1 µg of PCR products. After DNA damage and end repair, the SMRTbell adapters were ligated onto the PCR amplicons, followed by purification with 0.6 volumes of Agencourt AMPure PB (Pacific Biosciences) with 10-minute incubation on a vortex mixer. Primer annealing and DNA polymerase binding were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, sequencing primers were annealed to the template at a final concentration of 0.833 nM by denaturing the primer at 80 °C for 2 min and cooling to 4 °C before incubation with the library at 20 °C for 30 min. Distributions of SMRTbell size are presented in Supplementary Fig. 7.

This library underwent sequential DNA replication, with DNA polymerase detachment as replication limitation, and was analyzed by IsoSeq2 pipeline using SMRTlink18 with the following settings: maximum dropped fraction, 0.8; maximum subread length, 15,000; minimum subread length, 50; minimum number of passes, 1; minimum predicted accuracy, 0.8; minimum read score, 0.65; minimum SNR, 3.75; minimum Z score, −9999; minimum quiver, 0.99; trim QVs 3′, 30; trim QVs 5′, 100; minimum sequence length, 200; polish CCS, false; emit individual QVs, false; and required polyA, true. In IsoSeq, consensus reads “Read of Insert (RoI)” were obtained. RoIs with both cDNA primers and poly(A) were defined as full-length (FL) reads, and others were defined as non–full-length reads. IsoSeq clustered these reads into isoform sequences using an algorithm called ICE. “Polished” reads from the algorithm (IsoSeq2 output files polished_hq.fastq and polished_lq.fastq) were subjected to further analyses. Note that those reads do not necessarily represent non-redundant isoforms due to the characteristics of ICE and natural 5′ degradation of RNA.

Hybrid error correction

We used LoRDEC64 for hybrid error correction of IsoSeq reads with RNA-seq data. LoRDEC was executed with following commands:

lordec-build-SR-graph -T 3 -2 <RNA-seq_interleaved.fastq>-k 19 -s 3 -g

lordec-correct -T 8 -i <Isoseq_reads.fastq>-k 19 -s 3 -2 <RNA-seq_interleaved.fastq>-o <corrected_Isoseq.fastq>

Mapping of corrected IsoSeq reads

Next, IsoSeq reads were mapped to the hg38 reference assembly by Minimap265 using two similar commands to retrieve results as both SAM and PAF formats under the same conditions:

minimap2 -ax splice -uf -C5 –secondary=no <GRCh38.mmi><corrected_Isoseq.fastq>

minimap2 -cx splice -uf -C5 –cs –secondary=no <GRCh38.mmi><corrected_Isoseq.fastq>

We filtered IsoSeq reads with mapping quality greater than 50.

Intra-/inter-sample collapsing IsoSeq reads

Intra-sample integration of mapped IsoSeq reads, followed by inter-sample integration, was performed using our R code. For multi-exon transcripts, we merged IsoSeq reads with the same splice junctions. The most upstream TSS and the most downstream TTS of original transcripts of merged isoforms were defined as the TSS and TTS of the merged isoforms, respectively, with all the original TSS and TTS information linked and retained. We combined 5´ truncated multi-exon isoforms with longer and compatible isoforms for each sample separately (meaning, we treated them as fragments of longer transcripts.) On the other hand, in order to detect correct exon–intron structures from transcripts expressed in target cells, we considered those truncated transcripts as independent transcripts of longer transcripts from other samples unless they shared all splice junctions. For single-exon transcripts, we consolidated reads with other single-exon transcripts if the genomic range of the former overlapped with the latter read. We did not combine single-exon transcripts with longer multi-exon transcripts. Both intra-sample and inter-sample integrations were performed according to this procedure.

We considered that an isoform was detected in a particular sample only when there were non-truncated IsoSeq reads in the sample (i.e., multi-exon IsoSeq reads of which all splice junctions matched, or mono-exon IsoSeq reads with genomic range within the integrated isoform).

Isoform count was defined as the sum of IsoSeq read FL counts that were linked to a specific isoform but not to any other isoforms; we referred to this value as PBcount.

Classification and filtering with SQANTI

We classified and filtered curated isoforms with SQANTI27. For classification, we used the genomic range of isoforms in GTF format, TPM of RNA-seq yielded by Salmon, and the number of FL reads summed in the last section. SQANTI uses random forest to determine whether an isoform is an artifact. As in the primary setting, isoforms with all splicing junctions matching those in annotated transcripts (full-splice match) were set as true positives in the training data; true negatives were defined as those transcripts with at least one novel and non-canonical splicing junction. We used isoforms that passed the SQANTI filter as our full-length transcript library for downstream analyses.

Chimeric reads

Chimeric reads are mapped onto more than two genomic regions; however, because long reads yield a certain amount of sequencing error, there might be an uncertainty of several bp about the fusion sites. Therefore, when we found only one position with canonical splice junctions, as long as it was within the uncertainty range of the fusion sites, we selected the position as a fusion point. For reads with splice junctions as fusion points, we set an additional requirement that they have genomic breakpoints within 100,000 bp of the fusion points. For reads that were not confirmed, assuming that they had breakpoints on exonic regions, we set the requirement that there be genomic breakpoints within 100 bp of the fusion points. Of the three-piece fusion transcripts with two fusion points, we selected those with one linked to a genomic breakpoint, and the other one unlinked. Following that, we used blastn to manually search for possible genomic breakpoints that correspond with unlinked fusion points66.

A simulator for long-read RNA sequencing

Although multiple long-read genomic sequence generators have been developed for simulation67–69, none were designed for cDNA sequencing. Therefore, we created a simulator for long-read RNA sequencing, simlady (SIMulator for Long-read transcriptome Analysis with RNA DecaY model). In contrast to long-read genomic sequencing, in which reads are generated from the distribution of read length, reads are generated from template transcripts in long-read RNA sequencing. The lengths of generated reads could be different from the original template transcripts; we have focused on RNA 5′ degradation and sequencing error as the main reason for this. RNA decay is a major reason why transcript start sites (TSS) of IsoSeq reads can be inaccurate70. On the other hand, for the positions of transcript termination sites, it has been reported that there are only a few amounts of error24. RNA decay was fitted by gamma distribution. The ‘pelgam’ function implemented in ‘lmom’ R package was used for fitting. A public dataset that uses MCF-7 cell lines for IsoSeq (https://github.com/PacificBiosciences/DevNet/wiki/IsoSeq-Human-MCF7-Transcriptome) is often used in simulator evaluation68; we also used this dataset for evaluation. Universal Human Reference (brain, liver, and heart) IsoSeq data (https://github.com/PacificBiosciences/DevNet/wiki/Sequel-II-System-Data-Release:-Universal-Human-Reference-(UHR)-Iso-Seq), another public dataset, was used for validation. We investigated how much the TSS of FLNC reads were shortened according to the nearest upstream TSS in GENCODE. Using the gamma distribution, the shortened length matched well below 10,000 bp (Supplementary Figs. 2a–d). This distribution was extremely heavy-tailed, and barely matched the fitted curve above 10,000 bp. One possible explanation for this is that because the GENCODE TSS annotation was imperfect, there were FLNC reads that incorrectly linked to distant reference TSSs. As of sequence error model, we used the SimLoRD68 model. SimLoRD inserts errors in order not to change the read length, but the read length changes actively according to the error inserted. Because SMRT sequencing data has a transcript length–dependent distribution, each read is sampled according to the probability derived from fold change and transcript length in order to reconstitute this distribution.

Simulations with different settings

We generated two groups of short-read and long-read RNA-seq data from the GENCODE annotation, with the following parameters: number of samples per group, 8; fold change for DTU, 4; short-read length, 100 bp; short-read depth, 50,000,000 reads; and number of FLNC reads, 250,000. We changed these values one by one to investigate the effect on DTU inference (Supplementary Fig. 2). In detail, we defined the relative expression of all isoforms as 1 except for a randomly selected 10% of genes, for which we randomly selected 2 isoforms for DTU and assigned the pre-defined fold change value to one isoform in the first group and the other isoform in the second group. The ‘simulate_experiment_countmat’ function in the polyester R package71 was used for simulating short-read RNA-seq data; subsequently, the reads were shuffled because the reads were written out for each transcript. To simulate FLNC reads without specifying read length distribution, we used simlady, which generated reads under the log-normal distribution inherited from SimLoRD68. The FLNC reads were then processed to cluster reads by ‘isoseq3 cluster’ with the ‘–singletons’ option. Although IsoSeq3 discards singletons, we determined the number of FLNC read suitable for IsoSeq2, which additionally uses non-full-length reads and tolerates clusters with only one FLNC read. Therefore, we combined singletons with clustered reads and used them as input for MuSTA.

Simulations based on the breast cancer dataset

We generated two groups of short-read and long-read RNA-seq data from the FSM and NIC isoforms in the MuSTA-derived transcriptome generated from 22 breast cancer specimens. The number of samples per group was 8 (short-read) and 14 (long-read), as in the original data. We permutated the log-averaged expression of FSM isoforms and NIC isoforms separately. We randomly assigned DGE for 25% of all genes, and DTU for 10% of all genes so that 4% of genes would be assigned as both DGE and DTU. These values were approximately the same as the original breast cancer data at an FDR threshold of 0.05. The expression fold change between groups was set to 4 for all isoforms of DGE genes, such that the log-averaged expression remained the same. As for DTU genes, we shuffled all genes and tried to select two DTU isoforms for which one isoform had higher expression in the first group and the other had higher expression in the second group. That is, we selected two isoforms with the highest expression randomly from the following so that the NIC rate against all DTU isoforms reached the pre-defined value: (i) two FSM isoforms, (ii) one FSM isoform and one NIC isoform, or (iii) two NIC isoforms. Again, we set the expression fold change between groups to 4 for DTU isoforms so that the log-averaged expression remained the same. Short-read and long-read RNA-seq reads were simulated as described above, with the exception that the length distributions of polished reads in breast cancer data were permuted and used for the FLNC read-length distribution.

Differential gene expression

Differential gene expression was investigated with DESeq272 as described in ref. 73. Isoform expression data obtained using Salmon were imported into R and summarized at the gene level using tximport74.

Differential transcript usage

A comparison of state-of-the-art methods by Soneson et al.11 revealed that DEXSeq75 was most accurate. Therefore, we chose DEXSeq as the inference engine for differential transcript usage as described previously73. In brief, each isoform was treated as an exon, and a log-likelihood ratio test was performed under the setting with “~ sample + exon + subtype * exon” as the full model and “~ sample + exon” as the null model. To combine short-read RNA-seq data and full-length PBcount data, we concatenated both datasets and set “~ sample + exon + subtype * exon + data type * exon” as the full model and “~ sample + exon + data type * exon” as the null model. Note that this setting treated RNA-seq data and PBcount data derived from the same sample as biological replicates, whereas DEXSeq does not have a proper method for combining two technically replicated datasets with large batch effects, and we did observe a substantial difference between RNA-seq data and PBcount data. Although this could lead to an artificial increase in power, we obtained more conservative results from the concatenated data than from RNA-seq data in simulations (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Gene-level and transcript-level false discovery rates were calculated with stageR56.

Prefiltering of transcriptome

For pre-alignment prefiltering, we only retained those isoforms that had the first or second largest number of PBcount per gene in at least one sample and had PBcount ≥ 5 in all samples. Among these isoforms, up to 10 were chosen in descending order of PBcount. To avoid mis-mapping of RNA-seq, for each gene with no selected isoforms, we also retained one isoform with the largest PBcount. We defined the selected isoforms as “major” isoforms. For post-alignment prefiltering, we used the DRIMSeq76 filter and removed transcripts if their relative expression compared to the total expression of the related genes was lower than 0.1.

Overlap between MuSTA-transcriptome and unannotated open reading frames

The list of high-confidence translated open reading frames identified in human induced pluripotent stem cells and human foreskin fibroblast was obtained from ref. 29. We lifted the positions from Hg19 to Hg38, and retained those that were uniquely lifted. We counted the number of open reading frames whose genomic ranges did not overlap with any GENCODE genes and were completely covered by MuSTA-transcriptome.

Alternative splicing

We explored alternative splicing events of exon skipping/inclusion, alternative 5′, alternative 3′, mutually exclusive exons, and intron retention using the ‘generateEvents’ function of SUPPA277. Next, we used the ‘performPCA’ function implemented in psichomics78 for principle component analysis of splicing events as described in the vignettes of the psichomics software (https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/vignettes/psichomics/inst/doc/CLI_tutorial.html).

Domain prediction

We used HMMER79 to detect domains collected in Pfam80 (version 32.0) with the following command: - hmmscan –domtblout –noali -E 0.1 –domE 0.01 Pfam-A.hmm.

Quantitative PCR and sequencing of fusion points

RNA was extracted from cells using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). Total cellular RNA was converted into cDNA by reverse transcription (SuperScript IV VILO Master Mix; Thermo Fisher) using random primers. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using Power SYBR Green qPCR SuperMix-UDG with ROX (Thermo Fisher) on an Applied Biosystems PRISM 7900 Sequence Detection System. PCR conditions were as follows: 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 60 s. Complementary DNAs for fusion points were amplified by reverse-transcription PCR (RT-PCR) from RNA samples and subjected to Sanger sequencing. Primer sequences used in this study were as follows: IQCG-9-chr3-197892650-S: TGTGCTAAGTCACTGGCCTTTGTG; IQCG-9-chr3-197912810-AS: TGAGAACTTCTGATTCCCAGCCCT; IQCG-11-chr3-197892723-S: ATTTCTCCATCCAGAACTCCAGCC; IQCG-11-chr3-197914024-AS: GCTAACCTCAAGGACCAACTGCAA; TNS3-56-chr7-47304877-S: GAAGCAAAAGCCTGCTGAAAGGAG; TNS3-56-chr7-47328056-AS: AGCCCAAGGAGTTCCCTCTGTCT; TNS3-67-chr7-47304877-S: GAAGCAAAAGCCTGCTGAAAGGAG; TNS3-67-chr7-47344975-AS: GAGTCCATGTGTTCAACTCCAGCA; OGG1-Novel-Novel-S: AGAGGTGGCTCAGAAATTCCAAGG; OGG1-Novel-Novel-AS: CTTCCTTTCCCAGGCTCTTACCAA; SLC12A2_novel_SLC12A2-S: TTGGGGTATGGAGAGGAGCGTAAT; SLC12A2_novel_SLC12A2-AS: TGGCCACATTCCTATGATGAGC; HIST1H2AG_novel_ERVFRD-1-S: TGGAGTACAATGGTGTGATCTCGG; HIST1H2AG_novel_ERVFRD-1-AS: GTTCAGCCCTTGACTTGGGGTTTT.

Chromatin modifications in breast normal/cancer cell lines

ChIP-seq of chromatin modifications for MCF-7, MDA-MB-468, and MCF-10A were carried out by Franco HL et al.55, and subsequently collected, mapped to hg19, and peak-called using ChIP-Atlas81. We used the mapped data and the peak data with a threshold of q < 10−5 and lifted them to hg38.

Cell lines

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells and the murine mammary carcinoma cell line EMT6 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)-F12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (both from Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The human mammary gland epithelial cell line MCF10A was obtained from ATCC and maintained in DMEM-F12 supplemented with 5% (vol/vol) horse serum (Biowest, Nuaillé, France), recombinant human epidermal growth factor (20 ng/mL) (Peprotech, Cranbury, NJ, USA), bovine insulin (10 μg/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), hydrocortisone (0.5 μg/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich), and cholera toxin (100 ng/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich). MC38 (mouse colon carcinoma) cell line was obtained from Kerafast (Boston, MA, USA) and maintained in DMEM (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) supplemented with 10% FBS (Life Technologies). All cell lines were authenticated by the providers using karyotype, isoenzmes, and/or microsatellite profiling (short tandem repeat or simple sequence length polymorphism). Cultured cells were tested for mycoplasma contamination using the MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza).

Gene transduction

The coding sequences of genes were amplified by RT-PCR and inserted into the retroviral vector pMXs-ires-bsr. All cDNAs were verified by Sanger sequencing. To produce infectious viral particles, HEK293T cells were co-transfected with the indicated plasmids along with the packaging plasmids (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan).

In vivo mouse studies

Female C57BL/6J, BALB/c, and BALB/c-nu/nu mice (5–7 weeks of age) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories Japan (Yokohama, Japan) and used at 6–9 weeks of age. MC38 cells or EMT6 cells (1 × 106 cells) infected with retroviral vector expressing ERVFRD-1 or mock vector were subcutaneously inoculated into the flanks of the mice, and tumor size was monitored every 3 days. Tumor diameter was measured using calipers, and tumor volume was determined by calculating the volume of an ellipsoid using the following formula: length × width2 × 0.5. All mouse experiments were approved by the Animals Committee for Animal Experimentation of the National Cancer Center Japan. All experiments met the United States Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Statistics and reproducibility

Differential gene expression (DGE) was inferred using the Wald test under a negative binomial distribution implemented in DESeq272. Differential transcript usage (DTU) was calculated by the log-likelihood ratio test implemented in DEXSeq75. Enrichment of gene ontologies was calculated by the hypergeometric test. Student’s t-test was used for testing the difference of tumor weight in mouse models. To test the association between percent-spliced-in of TNS3 and prognosis, regression analyses under Cox proportional hazards models were performed for four indicators, overall survival (OS), disease-specific survival (DSS), disease-free interval (DFI), and progression-free interval (PFI)82, with race, sex, age at diagnosis, subtype, and TNS3 expression (Z-score normalized) as covariates. For DGE and DTU in breast cancer data, a two-tailed P < 0.01 was considered statistically significant, based on our observations in the simulation studies. For DGE in TNS3-expressing MCF10A cells, genes with two-tailed P < 0.1 were used for the subsequent hypergeometric test. Otherwise, a two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. In situations involving multiple tests, the false discovery rate was calculated using the Benjamini and Hochberg method, except that stage-wise correction was applied for DTU with StageR56.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms Miki Tamura, Ms Kaori Sugaya, Dr. Manabu Soda, and Dr. Yoshihiro Yamashita for technical assistance. We are grateful to all patients and families who contributed to this study. Computation time was provided by the Supercomputer System, Human Genome Center, the Institute of Medical Science, the University of Tokyo. This study was supported by grants from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (JP17am0001001 to H.M.; JP15cm0106085 to S.H.; JP19cm0106502 to M.K.), a grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) (16K07143 and 21H02772 to M.K.), and a grant from the UBE Industries Foundation (to M.K.).

Author contributions

S.N. developed the MuSTA pipeline and conducted experiments and data analysis. M.K. conducted experiments and supervised the study. K. Kobayashi provided clinical specimens and conducted experiments. N.M., T.O., S.H., and M.A. provided clinical specimens. K. Kawase, Y. Tanaka, S.I., F.K., S. Kawashima, and Y. Togashi prepared sequencing libraries and conducted experiments. T.U. and S. Kojima processed and analyzed sequenced data. S.N. and M.K. wrote the manuscript with comments from Y.S. and H.M.

Data availability

The raw sequencing data have been deposited in the Japanese Genotype-Phenotype Archive (https://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/jga/index-e.html) under accession number JGAS000095. The data set ID for the whole-genome sequence and RNA-seq is JGAD000095, and the dataset ID for Iso-seq is JGAD000457. Supplementary Data (the annotation of the MuSTA-derived transcriptome generated from 22 breast cancer specimens, the annotation of the novel predicted proteins, and the correlations of gene expression between intergenic genes and their neighbor genes) are available at Figshare83. TCGA data were obtained via cBioPortal (https://www.cbioportal.org/).

Code availability

MuSTA and simlady are freely available at https://github.com/shinichinamba/MuSTA and https://github.com/shinichinamba/simlady, respectively, under the MIT License. The other bioinformatic tools used in this study are freely available and listed below: Genomon60 (version 2.6.0), STAR61 (version 2.5.2a), RSEM63 (version 1.3.1), Salmon62 (version 0.12.0), SMRTlink18 (version 5.1.0.26412), LoRDEC64 (version 0.9), Minimap265 (version 2.12-r847-dirty), SQANTI27 (version 1.2), DRIMSeq76 (version 1.10.1), DESeq272 (version 1.22.2), DEXSeq75 (version 1.28.3), tximport74 (version 1.10.1), stageR56 (version 1.4.0), HMMER79 (version 3.1b2), SUPPA277 (version 2.3), psichomics78 (version 1.8.2), and BLAST66 (version 2.9.0+).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Communications Biology thanks Sanjeev Shukla, Ana Teresa Maia and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Bishoy Faltas and Christina Karlsson Rosenthal.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-021-02833-4.

References

- 1.Kim J, Eberwine J. RNA: state memory and mediator of cellular phenotype. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calabrese C, et al. Genomic basis for rna alterations in cancer. Nature. 2020;578:129–136. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1970-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danan-Gotthold M, et al. Identification of recurrent regulated alternative splicing events across human solid tumors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:5130–5144. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Climente-González H, Porta-Pardo E, Godzik A, Eyras E. The functional impact of alternative splicing in cancer. Cell Rep. 2017;20:2215–2226. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biswas K, et al. Intragenic DNA methylation and BORIS-mediated cancer-specific splicing contribute to the Warburg effect. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:11440–11445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1708447114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grelet S, et al. A regulated PNUTS mRNA to lncRNA splice switch mediates EMT and tumour progression. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017;19:1105–1115. doi: 10.1038/ncb3595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salton M, et al. Inhibition of vemurafenib-resistant melanoma by interference with pre-mRNA splicing. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7103. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang K, et al. The Cancer Genome Atlas Pan-Cancer analysis project. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1113–1120. doi: 10.1038/ng.2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shiraishi Y, et al. A comprehensive characterization of cis-acting splicing-associated variants in human cancer. Genome Res. 2018;28:1111–1125. doi: 10.1101/gr.231951.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farver C, et al. Comprehensive analysis of alternative splicing across tumors from 8,705 patients. Cancer Cell. 2018;34:211–224.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soneson, C., Matthes, K. L., Nowicka, M., Law, C. W. & Robinson, M. D. Isoform prefiltering improves performance of count-based methods for analysis of differential transcript usage. Genome Biol.17, 12 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Dueck H, et al. Deep sequencing reveals cell-type-specific patterns of single-cell transcriptome variation. Genome Biol. 2015;16:122. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0683-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tilgner H, Grubert F, Sharon D, Snyder MP. Defining a personal, allele-specific, and single-molecule long-read transcriptome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:9869–9874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400447111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS. Triple-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:1938–1948. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawazu M, et al. Integrative analysis of genomic alterations in triple-negative breast cancer in association with homologous recombination deficiency. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:1–23. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polak P, et al. A mutational signature reveals alterations underlying deficient homologous recombination repair in breast cancer. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:1476–1486. doi: 10.1038/ng.3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rhoads A, Au KF. PacBio sequencing and its applications. Genomics Proteom. Bioinformatics. 2015;13:278–289. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon SP, et al. Widespread polycistronic transcripts in fungi revealed by single-molecule mRNA sequencing. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0132628. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdel-Ghany SE, et al. A survey of the sorghum transcriptome using single-molecule long reads. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11706. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang B, et al. Unveiling the complexity of the maize transcriptome by single-molecule long-read sequencing. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:1–13. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sadler KC, et al. High resolution annotation of zebrafish transcriptome using long-read sequencing. Genome Res. 2018;28:1415–1425. doi: 10.1101/gr.223586.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tilgner H, et al. Comprehensive transcriptome analysis using synthetic long read sequencing reveals molecular co-association of distant splicing events. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:736–742. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gupta I, et al. Single-cell isoform RNA sequencing characterizes isoforms in thousands of cerebellar cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018;36:1197–1202. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anvar SY, et al. Full-length mRNA sequencing uncovers a widespread coupling between transcription initiation and mRNA processing. Genome Biol. 2018;19:1–18. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1418-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jing, Y. et al. Hybrid sequencing-based personal full-length transcriptomic analysis implicates proteostatic stress in metastatic ovarian cancer. Oncogene38, 3047–3060, 10.1038/s41388-018-0644-y (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Chen H, et al. Long‐read RNA sequencing identifies alternative splice variants in hepatocellular carcinoma and tumor‐specific isoforms. Hepatology. 2019;70:1011–1025. doi: 10.1002/hep.30500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]