Abstract

Assisted reproduction is presumed to increase monozygotic twin rates, with the possible contribution of laboratory and medical interventions. Monozygotic dichorionic gestations are supposed to originate from the splitting of an embryo during the first four days of development, before blastocyst formation. Single embryo transfers could result in dichorionic pregnancies, currently explained by embryo splitting as described in the worldwide used medical textbooks, or concomitant conception. However, such splitting has never been observed in human in vitro fertilization, and downregulated frozen cycles could also produce multiple gestations. Several models of the possible origins of dichorionicity have been suggested. However, some possible underlying mechanisms observed from assisted reproduction seem to have been overlooked. In this review, we aimed to document the current knowledge, criticize the accepted dogma, and propose new insights into the origin of zygosity and chorionicity.

Keywords: Multifetal gestations, Zygosity, Chorionicity, In vitro fertilization, Inner cell mass, Trophectoderm

Introduction

The overall twin birth rate in the USA in 2017 was 3.3% [1]. In assisted reproduction, the multiple pregnancy rate following single embryo transfer (SET) is 1.7% [2]. Classical twin studies have indicated that monozygotic (MZ) twins arise from a single fertilized egg and that they inherit identical genetic material [3]. Among liveborn MZ twins, 70–75% share one placenta with monochorionic (MC) diamniotic (DA) membranes, whereas 25–30% have entirely separate placentas and membranes [4]. The number of chorions and amniotic sacs is used to define the timing of MZ twinning (MZT). In this model, separate placentas indicate MZ dichorionic (DC) twinning, which is formed 0–3 days post-fertilization [5], prior to the formation of two distinct cell lines, inner cell mass (ICM) and trophectoderm (TE). These mechanisms are well accepted that they have been included in textbooks of medical education, embryology, and obstetrics that are used worldwide [6, 7].

While chorionicity can be determined with nearly 100% accuracy, zygosity can be predicted in only 55–65% of twin pregnancies by correlating the chorion type with the sex of the twins [8]. This is because same-sex DC twin gestations can either be MZ or dizygotic (DZ). Placental examination often cannot determine zygosity [9] and DNA fingerprinting, which is the gold standard for zygosity determination, is too expensive for routine practice. Monochorionicity has been considered to be diagnostic of monozygosity, wherein all monochorionic pairs are assumed to be monozygotic and are never genotyped unless grossly discordant for something more- or- less as compelling as sex. New and cost-effective methods have been proposed as alternative approaches for zygosity determination [8, 10, 11] but they were not widely implemented in routine practice. In clinical practice, the conventional classification remains widely used, as follows: monochorionicity confirms monozygosity, opposite-sex twins confirm dizygosity, and the zygosity of same sex DC twins remains uncertain until postnatal evaluation.

Current hypotheses

Humans and the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) are the only mammals that regularly produce MZ gestations [12]. Currently, four hypotheses could explain the mechanism of MZT via zygotic splitting: the cell repulsion hypothesis [13], the existence of codominant axes [14], depressed calcium levels in the early embryo [15], and the blastomere herniation hypothesis [4, 16]. Given that human blastomeres are totipotent and that artificially isolated blastomeres of four-cell stage human embryos have been demonstrated to develop in vitro into blastocysts with TE and ICM [17], the zygotic splitting model has been considered to be a specific mechanism of MZT.

The incidence of MZT is higher in pregnancies conceived after assisted reproduction than that in pregnancies via natural conception [18] even in the early years of extended culture to blastocyst stage, which is supposed to be one of the leading causes [19–23]. The proposed mechanisms as to how assisted reproduction contributes to MZT are controversial. According to early studies, assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) could potentially produce laboratory-related risks (e.g. creation of breaks in the zona pellucida (ZP)) or medical risks (e.g. aging of egg, delay in fertilization, or ovulatory drug-related hardening of the ZP) that contribute to the physical separation of an embryo into two entities [4]. Familial MZT could also be associated with inherited abnormality of the ZP or with some other mechanism, leading to the inability of the cells to adhere to one another [24]. Recently, blastocyst-stage embryo transfer [20, 25, 26] and artificial assisted hatching (AHA) have been reported to increase MZT rates in assisted reproduction [27, 28]. Younger women with high embryo quality were found to be more prone to MZT [29–32]. Whether patient age is an indirect factor remains debatable; moreover, hereditary factors influence the high incidence of MZT in fertility clinic patients, and a good ovarian function promotes the occurrence of MZT [33]. Blastocyst transfer is a significant risk factor for MZ DC twinning in fresh cycles. Interestingly, maternal age has been shown to play a more critical role in frozen cycles [34].

According to new findings, involving one of the largest patient cohorts on the effect of embryo biopsy, requiring blastocyst culture, ZP manipulation, and embryo cryopreservation, which are the most suspected techniques in assisted reproduction inducing MZT, the former claim seems to be broken. The incidence of MZT was not found to be different in embryo transfers with or without embryo biopsy [35]. Furthermore, maternal age, intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), AHA, and blastocyst transfer were not related to MZT [36]. Indeed, clustering of MZ twin pregnancies was observed across six-month intervals. A high-risk interval indicates that the high MZT rates in those periods cannot be explained by the risk factors commonly reported in the literature [37]. Atypical hatching of blastocysts and frozen embryo replacements leading to multiple pregnancies have been reported [38–40] and encountered by embryologists. However, DC pregnancies after SET have also been reported [41, 42]. The incidence of DC twinning after SET was found to be 0.31% in a pioneer study [43].

These occurrences of DC pregnancies as a result of SET have raised several questions [44]. Given that the accepted model implies that single blastocyst transfers can only give rise to MC gestations, concomitant spontaneous pregnancy stands as the most likely mechanism of DC gestations after a SET, although genetic evidence is lacking, especially for same-sex DC twins [45]. A recent report from the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART) shows that the rates for sex discordant pregnancies were similar in fresh and frozen embryo transfers in SET cycles. Cycles resulting in sex discordant pregnancies were more common in non-suppressed patients. Patients who had undergone bilateral tubal ligation had no sex discordant pregnancies supporting the occurrence of concomitant spontaneous pregnancies [2]. The same report also mentions that the findings do not support embryo manipulation (ICSI and AHA) or blastocyst transfer as risk factors for MZ pregnancies, and embryo splitting remains controversial. Unless genetic analysis of the offspring is performed, the answer remains unclear. Case reports showing DZ twins after SETs support the hypothesis involving spontaneous conception [46–51], but its relative contribution remains unknown.

Detailed examination of the comprehensive data published by Konno et al. reveals that DC gestations were much more relevant in controlled ovarian stimulation and assisted reproduction cycles than naturally conceived twins [52]. Apart from chorionicity, data on sex discordancy show that approximately 18% of twins that arose from SETs were DZ when Weinberg’s differential rule was applied [2]. However, 70% of twins that arose via SETs were DC [52], and DZT accounted for less than a third of the gestations, whereas 52% of the remaining DC gestations after SET were MZ.

The debate is not new. One of the most definitive studies on whether MZ twins share identical genetic information revealed that most MZ twin pairs are not identical; there may be significant discordance in terms of birth weight, genetic disease, and congenital abnormalities [53]. In the said study, postzygotic events were considered to lead to the formation of two or more cell clones in the ICM and the early stimulation of MZT events in the embryos. Furthermore, given that MZ twins share a common placenta, they are supposed to share the same pre-primordial germ cell mutations. However, only 50% of twin pairs share a mutation [54] under the observed rate of MZ pregnancies (70–75%), consistent with the MZT rates reported [2, 52].

Another mechanism underlying the formation of MZ DC twins explains that as has been documented in experimental mammals that the decay of the secondary oocyte may involve the movement of the second meiotic spindle back to the center of the cell, followed by a symmetrical division yielding two fertilizable daughter cells [55, 56], note that dichorionicity requires two shells of “outside” cells to differentiate within the morula, to divide and to enclose subsets of the inner cells into separate domains, each to form its surrounding trophoblast layer, for further development as DC twins; however, such a phenomenon is contradictory to the classical theory. The two fertilizable daughter cell theory is later described as the first zygotic division, wherein twin zygotes are generated instead of two blastomeres [57]. The same work also implied that chorionicity and amnionicity would not depend on embryo splitting but a fusion of membranes. Another splitting hypothesis similar to the twin zygote theory also claims that splitting occurs at the postzygotic two-cell stage, with each cell forming a distinct individual. If twin blastocysts together hatch from the ZP, DC DA twins will arise. If the two TEs fuse before hatching and the ICMs are separated within the shared TE, MC DA twins will arise. If the ICMs are fused and eventually separated, MC MA twins will arise [58]. Consecutive publications criticized the twin zygote theory. The formation of twin zygotes rather than sister blastomeres does not constitute a barrier to the aggregation and the consequent formation of a common blastocyst. This occurs very readily between the cleavage stage embryos, in zygotes of different genotypes, and even of different species [59, 60]. Other processes supporting the cellular axis hypothesis are patterning and polarization [61]. Here, either disruption or duplication events in the formation of these parameters could prevent or contribute to a twinning event. However, there appears to be no direct evidence supporting this concept. Novel changes in the X chromosome and the presence of candidate variants across autosomes might also be responsible for MZT [62]. It remains unclear however as to how much chromosomal aberrations contribute to twinning rates.

To date, there are four hypotheses explaining the formation of MZ DC twins, as follows:

Embryo splitting during the first three days of development

Two fertilizable daughter cells arise from one oocyte

Concomitant spontaneous conception, which is actually DZT, and

Cellular polarization defects.

Our recommendations

As demonstrated, monochorionicity does not guarantee monozygosity [63–67], and MZ twins do not always have identical genetic constitutions [54, 68, 69] and even phenotypes [70]. Moreover, SETs can lead to MZ DC twins [41, 42, 45, 52, 71, 72].

To date, the four hypotheses seem unprovable. Although millions of oocytes and embryos have been observed in assisted reproduction, except artificially created embryos, there has not been even one report showing two embryos developing from one embryo with two distinct TEs, or one oocyte yielding two fertilizable cells, despite the introduction of advanced micromanipulation techniques (e.g., polar body, blastomere, and TE biopsies; artificial oocyte activation; ZP drilling; AHA; and defragmentation). Moreover, squeezing of ICM during incomplete hatching in vitro as the most accepted hypothesis that would explain embryo splitting, which could only be demonstrated in mice [73] has been shown not to increase MZ twinning rates in human assisted reproduction [74]. Artificially created twin embryos from either the early (2 to 5 blastomeres) or late (6 to 10 blastomeres) cleavage stage have been shown to yield poor ICM quality and developmental delay. The culture of those embryos beyond Day 6 was unsuccessful and none of the embryos gave rise to human embryonic stem cell lines under standardized culture protocols, despite the observation of distinguishable ICM-like structures [75]. These findings suggest that the developmental clock of the human embryo will impose various limitations if embryo splitting took place at an early stage.

Since it has been proven that SETs could give rise to MZ DC twins, spontaneous conception also falls short of explaining the mechanisms underlying the formation of MZ DC twins. It has also been reported that downregulated, controlled frozen embryo replacement cycles (excluding the possibility of concomitant spontaneous pregnancy) could produce MZ twins [76].

Here, we hypothesize two mechanisms for two different situations to explain the origin of MZ DC gestations: assisted reproduction, and natural conception.

In assisted reproduction, there appears to be an underestimated phenomenon, ICM splitting, which is rare but has been demonstrated [77, 78], especially with the help of advanced time-lapse imaging technology [79]. Given that the classical hypothesis of embryo splitting was not observed and was not proven to occur within the first three days, the initiation of both MZ MC and MZ DC twins should involve a common precursor, which can be a blastocyst with two ICMs (Figs. 1, 2). Therefore, the chorionic differentiation should occur within the uterus in vivo, which cannot be observed in vitro, during the implantation process, or at a later time. The MZ DC twinning process is more likely to result from an embryo with dual ICMs, allowing the implantation of two embryos that share either one or two chorions, but that did not involve embryo splitting. Besides, the grade and looseness of the ICM, particularly blastocysts that contain decompacting ICMs, have also been shown to lead to the development of MC DA twins [80], probably with similar ICM splitting vulnerability. The development of MZ DCT may also be due to unobservable dual ICM during embryo evaluation. According to our model, chorionicity might be characterized by a series of events during implantation leading to the development of one or two chorions or possibly even the development of chorion via the splitting of the epithelial epiblast a few days later. As demonstrated in primates, the first syncytiotrophoblast cells, which are the pioneer cells penetrating uterine endometrium, are initially formed near the ICM [81]: Moreover, in vitro studies have shown that the invasion of human syncytiotrophoblast into the endometrial epithelial cells occurs in multiple regions [82]: both phenomena could be the events underlying the origin of MZ MC and MZ DC twins. Although current literature and our recommendation might not be sufficient to reject the former hypotheses, this novel process may lead to MZ MC and MZ DC twins in assisted reproduction and natural conception. However, our hypothesis remains to be proven unless demonstrating the formation of DCT after the transfer of a blastocyst with two ICMs. Retrospective scrutiny of the digital time-lapse recordings of DC gestations resulting from SETs could help to prove our hypothesis.

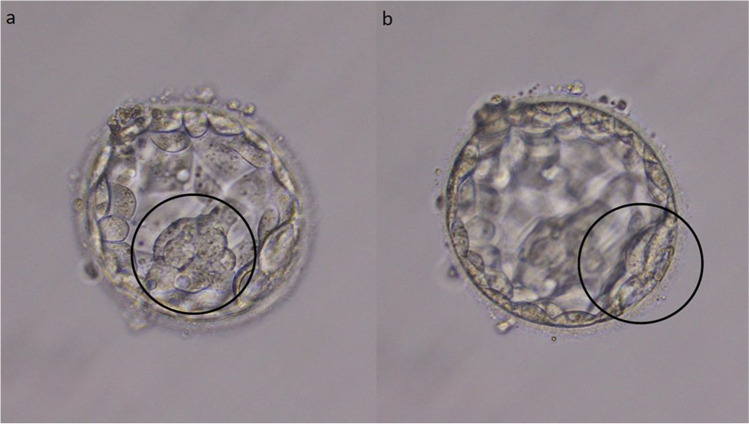

Fig. 1.

Two thin, loose, and decompacted possible ICMs within the same embryo (a, b). The transfer of this embryo did not result in a viable pregnancy

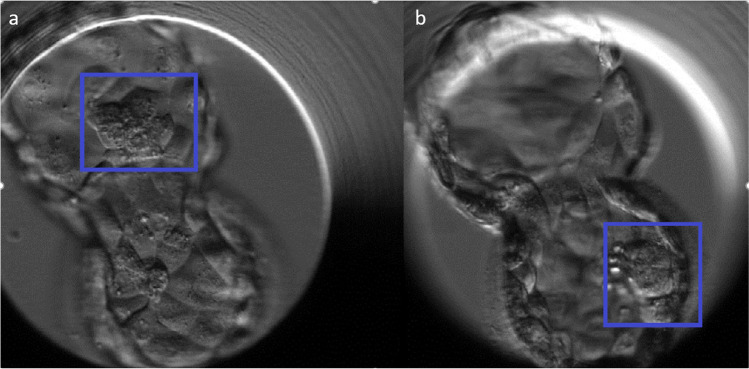

Fig. 2.

Time-lapse imaging of two ICMs within the same embryo (a, b), which resulted in a MC triamniotic gestation *Reprinted from “Time-lapse imaging of inner cell mass splitting with monochorionic triamniotic triplets after elective single embryo transfer: a case report”, Vol 38/Issue 4, K. Sutherland, J. Leitch, H. Lyall, and B. J. Woodward, Pages 491–496,

Copyright 2019, with permission from Elsevier (5,095,301,230,968).

The mechanism of the production of multiple ICMs has never been studied before. However, there appear to be some clues from basic science which could potentially uncover the black box. Due to ethical difficulties surrounding human embryo experimentation, the majority of the studies on early embryo development have been performed on animal models, particularly in mice. However, the pre and peri-implantation of human and mouse embryos are not identical; the timing of zygotic genomic activation is much later in human embryos, at the eight-cell stage [83]. In addition, the timing of the expression of key transcription factors for TE and ICM differentiation does not occur until the late blastocyst stage in the human embryo [84] which is quite later than in mice [85, 86]. Consistently, isolated TE and ICMs from human early blastocysts were found to regenerate both TE and ICM cells [87] which does not occur in mice [88]. Both the segregation of TE and ICM and also cellular plasticity are different in humans than in mice. In mice, blastomeres of 32-cell embryos appear to lose their plasticity, developing only into ICM or TE, depending on the positioning of the cells, e.g., inner, or outer region, respectively [88]. By contrast, the fate of human blastomeres can remain plastic until relatively advanced stages of development, which has been shown after isolation and reaggregation of human outer cells can reconstitute an embryo able to cavitate and form an ICM [87]. This plasticity might be one explanation of the generation of multiple ICMs in human blastocysts.

Another overlooked phenomenon when explaining zygosity and chorionicity arises from the lack of information on zygosity determination in same-sex twins, as mentioned earlier. As zygosity was not determined in nearly all same-sex MZ DC twins, then the conjoined oocytes within the same ZP, separated by a thinner ZP plate [89, 90] (Fig. 3a) which are retrieved from binovular follicles could explain some of the MZ DC cases, especially in natural conception, as conjoined oocytes are rarely inseminated by ICSI in assisted reproduction. Accordingly, some same-sex MZ twins might actually be DZ twins, in contrast with the classical hypothesis [91]. The human ovary may contain binovular or polyovular follicles at birth, but this phenomenon is unusual later in life [92]. It has been reported that 15 out of 631 oocyte recoveries (2.4%) involve conjoined oocytes [93]. Their incidence may increase due to ovarian stimulation. Selective fertilization of a single mature oocyte in a binovular ZP via ICSI can lead to competent embryo development (Fig. 3b). It can prevent undesired consequences that may result when two oocytes are fertilized in the course of conventional in vitro fertilization [94–97], as well as in natural conception, where both conjoined oocytes can be fertilized separately. In the case of two mature conjoined oocytes, they can be separately injected and transferred after the separation of two blastocysts by LASER shots. This approach has been shown to result in a DZ twin delivery [90]. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that MC twins could be dizygous [98], supporting our hypothesis that at least some of the MZ DC twins might have arisen from conjoined oocytes (true DZ twins) both fertilized and implanted, allowing for the development of two separate chorions.

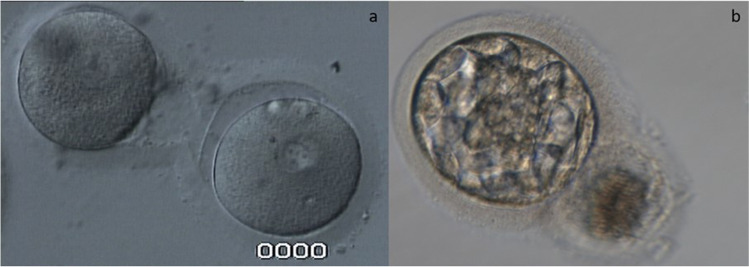

Fig. 3.

Conjoined oocytes within the same ZP (a). A high-grade blastocyst developed from one of the conjoined oocytes (b)

Conclusion and future perspectives

Spontaneous concomitant conception in assisted reproduction represents only one-third of DCT events, wherein two-thirds of DC twins arise via MZT. SETs can result in MZ DC gestations. Several models have been proposed to explain chorionicity and zygosity. However, the early embryo splitting, and two fertilizable daughter cell models remain myths. Moreover, physical ICM splitting during incomplete hatching does not seem to contribute to MZ DCT formation. To the best of our knowledge, implantation of a blastocyst with two ICMs appears to be an explanation for MZ DC gestations, as visualized in human in vitro fertilization experience. However, it must be considered that caution should be taken to avoid multiple gestations while transferring such embryos. In natural conception, conjoined oocytes might represent the origin of some of the DC gestations, which were actually DZ. The current information on twinning should be re-discussed in light of the human in vitro fertilization data, and new editions of widely used medical and biological textbooks should be updated. Moreover, future molecular studies are warranted to prove these concepts.

Acknowledgements

Figure 2 is reprinted from “Time-lapse imaging of inner cell mass splitting with monochorionic triamniotic triplets after elective single embryo transfer: a case report”, Vol 38/Issue 4, K. Sutherland, J. Leitch, H. Lyall, and B. J. Woodward, Pages 491–496, Copyright 2019, with permission from Elsevier (5,095,301,230,968).

We would like to thank Halil Ruso and Süreyya Melil for providing the images for Fig. 3.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Enver Kerem Dirican and Safak Olgan are contributed equally this work as principal investigators

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Enver Kerem Dirican, Email: keremdirican@gmail.com.

Safak Olgan, Email: safakolgan@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Jha P, Morgan TA, Kennedy A. US evaluation of twin pregnancies: importance of chorionicity and amnionicity. Radiographics. 2019;39(7):2146–2166. doi: 10.1148/rg.2019190042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vega M, et al. Not all twins are monozygotic after elective single embryo transfer: analysis of 32,600 elective single embryo transfer cycles as reported to the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. Fertil Steril. 2018;109(1):118–122. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boomsma D, Busjahn A, Peltonen L. Classical twin studies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3(11):872–882. doi: 10.1038/nrg932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall JG. Twinning. Lancet. 2003;362(9385):735–743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14237-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corner GW. The observed embryology of human single-ovum twins and other multiple births. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1955;70(5):933–951. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(55)90001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham F, et al. Williams obstetrics (24e). New York: McGraw-Hill; 2014.

- 7.Gilbert S. Developmental biology (10e). Sunderland MA: Sinauer Associates Inc.; 2014.

- 8.Tong S, Vollenhoven B, Meagher S. Determining zygosity in early pregnancy by ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;23(1):36–37. doi: 10.1002/uog.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scardo JA, Ellings JM, Newman RB. Prospective determination of chorionicity, amnionicity, and zygosity in twin gestations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173(5):1376–1380. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90619-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng J, et al. Effective noninvasive zygosity determination by maternal plasma target region sequencing. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e65050. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zou Z, et al. Unusual twinning: additional findings during prenatal diagnosis of twin zygosity by single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array. Prenat Diagn. 2018;38(6):428–434. doi: 10.1002/pd.5255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blickstein I, Keith LG. On the possible cause of monozygotic twinning: lessons from the 9-banded armadillo and from assisted reproduction. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2007;10(2):394–399. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.2.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall JG. Twins and twinning. Am J Med Genet. 1996;61(3):202–204. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960122)61:3<202::AID-AJMG2>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baldwin VJ. Pathology of multiple pregnancy. Springer; 1994. Anomalous development of twins; pp. 169–197. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steinman G, Valderrama E. Mechanisms of twinning. III. Placentation, calcium reduction and modified compaction. J Reprod Med. 2001;46(11):995–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blickstein I. Estimation of iatrogenic monozygotic twinning rate following assisted reproduction: pitfalls and caveats. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(2):365–368. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van de Velde H, et al. The four blastomeres of a 4-cell stage human embryo are able to develop individually into blastocysts with inner cell mass and trophectoderm. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(8):1742–1747. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.da Costa AA, et al. Monozygotic twins and transfer at the blastocyst stage after ICSI. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(2):333–336. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milki AA, et al. Incidence of monozygotic twinning with blastocyst transfer compared to cleavage-stage transfer. Fertil Steril. 2003;79(3):503–506. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04754-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanter JR, et al. Trends and correlates of monozygotic twinning after single embryo transfer. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):111–117. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ding J, et al. The effect of blastocyst transfer on newborn sex ratio and monozygotic twinning rate: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2018;37(3):292–303. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2018.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mateizel I, et al. Do ARTs affect the incidence of monozygotic twinning? Hum Reprod. 2016;31(11):2435–2441. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hviid KVR, et al. Determinants of monozygotic twinning in ART: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2018;24(4):468–483. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmy006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Healey SC, et al. Height discordance in monozygotic females is not attributable to discordant inactivation of X-linked stature determining genes. Twin Res. 2001;4(1):19–24. doi: 10.1375/1369052012100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hattori H, et al. The risk of secondary sex ratio imbalance and increased monozygotic twinning after blastocyst transfer: data from the Japan Environment and Children's Study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2019;17(1):27. doi: 10.1186/s12958-019-0471-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Busnelli A, et al. Risk factors for monozygotic twinning after in vitro fertilization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2019;111(2):302–317. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McLaughlin JE, et al. Does assisted hatching affect live birth in fresh, first cycle in vitro fertilization in good and poor prognosis patients? J Assist Reprod Genet. 2019;36(12):2425–2433. doi: 10.1007/s10815-019-01619-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ikemoto Y, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of zygotic splitting after 937 848 single embryo transfer cycles. Hum Reprod. 2018;33(11):1984–1991. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Franasiak JM, et al. Blastocyst transfer is not associated with increased rates of monozygotic twins when controlling for embryo cohort quality. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(1):95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knopman JM, et al. What makes them split? Identifying risk factors that lead to monozygotic twins after in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(1):82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu X, Shi J. Maternal age is associated with embryo splitting after single embryo transfer: a retrospective cohort study. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021;38(1):79–83. doi: 10.1007/s10815-020-01988-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu S, et al. High grade trophectoderm is associated with monozygotic twinning in frozen-thawed single blastocyst transfer. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2021;304:271–277. doi: 10.1007/s00404-020-05928-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sobek A, Jr, et al. High incidence of monozygotic twinning after assisted reproduction is related to genetic information, but not to assisted reproduction technology itself. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(3):756–760. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.12.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song B, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of monochorionic diamniotic twinning after assisted reproduction: a six-year experience base on a large cohort of pregnancies. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0186813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kamath MS, Antonisamy B, Sunkara SK. Zygotic splitting following embryo biopsy: a cohort study of 207 697 single-embryo transfers following IVF treatment. BJOG. 2020;127(5):562–569. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu D, et al. Monozygotic twinning after in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection treatment is not related to advanced maternal age, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, assisted hatching, or blastocyst transfer. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;53(3):324–329. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vaughan DA, et al. Clustering of monozygotic twinning in IVF. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016;33(1):19–26. doi: 10.1007/s10815-015-0616-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Behr B, Milki AA. Visualization of atypical hatching of a human blastocyst in vitro forming two identical embryos. Fertil Steril. 2003;80(6):1502–1503. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shibuya Y, Kyono K. A successful birth of healthy monozygotic dichorionic diamniotic (DD) twins of the same gender following a single vitrified-warmed blastocyst transfer. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2012;29(3):255–257. doi: 10.1007/s10815-011-9707-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kyono K. The precise timing of embryo splitting for monozygotic dichorionic diamniotic twins: when does embryo splitting for monozygotic dichorionic diamniotic twins occur? Evidence for splitting at the morula/blastocyst stage from studies of in vitro fertilization. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2013;16(4):827–832. doi: 10.1017/thg.2013.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li H, Shen T, Sun X. Monozygotic dichorionic-diamniotic pregnancies following single frozen-thawed blastocyst transfer: a retrospective case series. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):768. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-03450-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sundaram V, Ribeiro S, Noel M. Multi-chorionic pregnancies following single embryo transfer at the blastocyst stage: a case series and review of the literature. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;35(12):2109–2117. doi: 10.1007/s10815-018-1329-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawachiya S, et al. Incidence of dichorionic diamniotic twins after single blastocyst transfer. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:S68. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kyono K, et al. When is the actual splitting time of the embryo to develop a monozygotic dichorionic diamniotic (DD) twins following a single embryo transfer? Fertil Steril. 2011;96(3):S275. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tocino A, et al. Monozygotic twinning after assisted reproductive technologies: a case report of asymmetric development and incidence during 19 years in an international group of in vitro fertilization clinics. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(5):1185–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kallen CB. Fraternal twins after elective single-embryo transfers: a lesson in never saying "never". Fertil Steril. 2018;109(1):63. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van der Hoorn ML, et al. Dizygotic twin pregnancy after transfer of one embryo. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(2):805.e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Osianlis T, et al. Incidence and zygosity of twin births following transfers using a single fresh or frozen embryo. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(7):1438–1443. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takehara I, et al. Dizygotic twin pregnancy after single embryo transfer: a case report and review of the literature. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2014;31(4):443–446. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-0170-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sugawara N, et al. Sex-discordant twins despite single embryo transfer: a report of two cases. Reprod Med Biol. 2010;9(3):169–172. doi: 10.1007/s12522-010-0048-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bettio D, et al. 45, X product of conception after preimplantation genetic diagnosis and euploid embryo transfer: evidence of a spontaneous conception confirmed by DNA fingerprinting. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2016;14(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s12958-016-0190-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Konno H, et al. The incidence of dichorionic diamniotic twin pregnancy after single blastocyst embryo transfer and zygosity: 8 years of single-center experience. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2020;23(1):51–54. doi: 10.1017/thg.2020.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Machin GA. Some causes of genotypic and phenotypic discordance in monozygotic twin pairs. Am J Med Genet. 1996;61(3):216–228. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960122)61:3<216::AID-AJMG5>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jonsson H, et al. Differences between germline genomes of monozygotic twins. Nat Genet. 2021;53(1):27–34. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-00755-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boklage CE. Traces of embryogenesis are the same in monozygotic and dizygotic twins: not compatible with double ovulation. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(6):1255–1266. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boklage CE. The organization of the oocyte and embryogenesis in twinning and fusion malformations. Acta Genet Med Gemellol (Roma) 1987;36(3):421–431. doi: 10.1017/s000156600000619x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Herranz G. The timing of monozygotic twinning: a criticism of the common model. Zygote. 2015;23(1):27–40. doi: 10.1017/S0967199413000257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McNamara HC, et al. A review of the mechanisms and evidence for typical and atypical twinning. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(2):172–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.10.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gardner RL. The timing of monozygotic twinning: a pro-life challenge to conventional scientific wisdom. Reprod Biomed Online. 2014;28(3):276–278. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Denker HW. Comment on G. Herranz: The timing of monozygotic twinning: a criticism of the common model. Zygote (2013) Zygote. 2015;23(2):312–4. doi: 10.1017/S0967199413000579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scott L. The origin of monozygotic twinning. Reprod Biomed Online. 2002;5(3):276–284. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61833-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu S, et al. Four-generation pedigree of monozygotic female twins reveals genetic factors in twinning process by whole-genome sequencing. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2018;21(5):361–368. doi: 10.1017/thg.2018.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vázquez Rodríguez S, et al. Sex-discordant monochorionic dizygotic twins: a case report. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;38(2):279–281. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2017.1340934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Uysal N, et al. Fetal sex discordance in a monochorionic twin pregnancy following intracytoplasmic sperm injection: a case report of chimerism and review of the literature. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2018;44(3):576–582. doi: 10.1111/jog.13514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rodriguez-Buritica D, et al. Sex-discordant monochorionic twins with blood and tissue chimerism. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167a(4):872–7. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee HJ, et al. Monochorionic dizygotic twins with discordant sex and confined blood chimerism. Eur J Pediatr. 2014;173(9):1249–1252. doi: 10.1007/s00431-014-2312-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Souter VL, et al. A report of dizygous monochorionic twins. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(2):154–158. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Turrina S, et al. Monozygotic twins: identical or distinguishable for science and law? Med Sci Law. 2021;61(1_suppl):62–66. doi: 10.1177/0025802420922335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rolf B, Krawczak M. The germlines of male monozygotic (MZ) twins: very similar, but not identical. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2021;50:102408. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2020.102408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Barnes-Davis ME, Cortezzo DE. Two cases of atypical twinning: phenotypically discordant monozygotic and conjoined twins. Clin Case Rep. 2019;7(5):920–925. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yamashita S, et al. Analysis of 122 triplet and one quadruplet pregnancies after single embryo transfer in Japan. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;40(3):374–380. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2019.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dziadosz M, Evans MI. Re-thinking elective single embryo transfer: increased risk of monochorionic twinning - a systematic review. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2017;42(2):81–91. doi: 10.1159/000464286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yan Z, et al. Eight-shaped hatching increases the risk of inner cell mass splitting in extended mouse embryo culture. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12):e0145172–e0145172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gu YF, et al. Inner cell mass incarceration in 8-shaped blastocysts does not increase monozygotic twinning in preimplantation genetic diagnosis and screening patients. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0190776. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Noli L, et al. Developmental clock compromises human twin model created by embryo splitting. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(12):2774–2784. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bos-Mikich A. Monozygotic twinning in the IVF era: is it time to change existing concepts? J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;35(12):2119–2120. doi: 10.1007/s10815-018-1364-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Noli L, et al. Discordant growth of monozygotic twins starts at the blastocyst stage: a case study. Stem cell reports. 2015;5(6):946–953. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sills ES, Tucker MJ, Palermo GD. Assisted reproductive technologies and monozygous twins: implications for future study and clinical practice. Twin Res. 2000;3(4):217–223. doi: 10.1375/136905200320565184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sutherland K, et al. Time-lapse imaging of inner cell mass splitting with monochorionic triamniotic triplets after elective single embryo transfer: a case report. Reprod Biomed Online. 2019;38(4):491–496. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2018.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Otsuki J, et al. Grade and looseness of the inner cell mass may lead to the development of monochorionic diamniotic twins. Fertil Steril. 2016;106(3):640–644. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Carson DD, et al. Embryo implantation. Dev Biol. 2000;223(2):217–237. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ruane PT, et al. Trophectoderm differentiation to invasive syncytiotrophoblast is induced by endometrial epithelial cells during human embryo implantation. bioRxiv. Preprint. 2020. 10.1101/2020.10.02.323659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Rossant J, Tam PPL. New insights into early human development: lessons for stem cell derivation and differentiation. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;20(1):18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Niakan KK, Eggan K. Analysis of human embryos from zygote to blastocyst reveals distinct gene expression patterns relative to the mouse. Dev Biol. 2013;375(1):54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ralston A, Rossant J. Cdx2 acts downstream of cell polarization to cell-autonomously promote trophectoderm fate in the early mouse embryo. Dev Biol. 2008;313(2):614–629. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Palmieri SL, et al. Oct-4 transcription factor is differentially expressed in the mouse embryo during establishment of the first two extraembryonic cell lineages involved in implantation. Dev Biol. 1994;166(1):259–267. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.De Paepe C, et al. Human trophectoderm cells are not yet committed. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(3):740–749. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Suwińska A, et al. Blastomeres of the mouse embryo lose totipotency after the fifth cleavage division: expression of Cdx2 and Oct4 and developmental potential of inner and outer blastomeres of 16- and 32-cell embryos. Dev Biol. 2008;322(1):133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cummins L, Koch J, Kilani S. Live birth resulting from a conjoined oocyte confirmed as euploid using array CGH: a case report. Reprod Biomed Online. 2016;32(1):62–65. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2015.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Magdi Y. Dizygotic twin from conjoined oocytes: a case report. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020;37(6):1367–1370. doi: 10.1007/s10815-020-01772-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rosenbusch B, Hancke K. Conjoined human oocytes observed during assisted reproduction: description of three cases and review of the literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2012;53(1):189–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Papadaki L. Binovular follicles in the adult human ovary. Fertil Steril. 1978;29(3):342–350. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)43164-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ron-El R, et al. Binovular human ovarian follicles associated with in vitro fertilization: incidence and outcome. Fertil Steril. 1990;54(5):869–872. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)53948-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Safran A, et al. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection allows fertilization and development of a chromosomally balanced embryo from a binovular zona pellucida. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(9):2575–2578. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.9.2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Vicdan K, et al. Fertilization and development of a blastocyst-stage embryo after selective intracytoplasmic sperm injection of a mature oocyte from a binovular zona pellucida: a case report. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1999;16(7):355–357. doi: 10.1023/A:1020537812619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Turkalj B, Kotanidis L, Nikolettos N. Binovular complexes after ovarian stimulation. A report of four cases Hippokratia. 2013;17(2):169–170. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yano K, et al. Repeated collection of conjoined oocytes from a patient with polycystic ovary syndrome, resulting in one successful live birth from frozen thawed blastocyst transfer: a case report. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017;34(11):1547–1552. doi: 10.1007/s10815-017-1012-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kanda T, Ogawa M, Sato K. Confined blood chimerism in monochorionic dizygotic twins conceived spontaneously. AJP Rep. 2013;3(1):33–36. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1331377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.