Abstract

Osteoarticular Tuberculosis (TB) of the Sacroiliac (SI) joint is an uncommon site affected by Mycobacterium Tuberculosis infection. The SI joint is involved in approximately 5–10% of all cases of TB. Diagnosis of SI joint TB can be delayed in early stages due to its varied and hidden presentation and probability of being confused with other spinal diseases. Delay in diagnosis can lead to chronic pain, joint destruction, and a natural progression to symptomatic bony ankylosis. A focused clinical examination, complementary imaging, microbiological and histopathological confirmation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis can direct a targeted therapy. Anti-Tubercular Therapy (ATT) regime remains a cornerstone in the overall management of SI joint TB. Early diagnosis allows conservative or non-operative management. Surgical interventions like abscess drainage, debridement, and arthrodesis with or without bone grafting may be required to achieve an excellent functional outcome.

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Tuberculosis, Osteoarticular, Sacroiliac joint, Diagnosis, Treatment

1. Introduction

Predominantly a respiratory illness, osteoarticular Tuberculosis (TB) accounts for 1–5% of all tubercular infections, principally affecting the spine and weight-bearing joints of the lower limb.1 The Sacro-iliac joint (SIJ) being a deep-seated joint; is an uncommon site to be affected by TB with an reported incidence of approximately 5–10% of all cases of skeletal TB.1,2 It is a common cause of misdiagnosis, being treated as chronic low back pain or sciatica before a definitive diagnosis is made.3 Tuberculosis is still an essential cause of subacute or chronic sacroiliitis in low middle-income countries. SIJ TB should be diligently distinguished from other known causes of chronic sacroiliitis which have rheumatic, degenerative, non-degenerative aetiologies such as Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE), Ankylosing Spondyloarthritis, Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Gout, Brucellosis and Osteoarthritis.4, 5, 6 Though pyogenic sacroiliitis is most common form of infectious sacroiliitis, SIJ TB due to Drug-resistant TB is an increasing public health threat with the rise in Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infections, population migration and advent of immunosuppressants.7,8 Consequently, it is essential to make early and correct diagnosis to prevent long term morbidity due to SIJ TB.

In this review, we consider the varied clinical presentation of SIJ TB, highlight the findings of complementary imaging modalities undertaken to assess this condition and evaluate current concepts in the management of this disease.

Search Strategy: We carried out a comprehensive review of the available English literature using suitable keywords such as ‘Mycobacterium tuberculosis’ ‘osteoarticular’, ‘sacroiliac joint’ in all age groups on the search engine of PubMed, Google scholar and Scopus between 1988 and 2017. Case reports and articles with less than four patients have been excluded for the review and analysis (Table 1). Relevant articles were chosen to write this narrative review. (2,3, 9-16).

Table 1.

Series of previously reported cases of tubercular sacroilitis in English literature.

| Author year | Cases | Gender | Age (in years) | Kim Classification types | Duration from initial symptoms to final diagnosis | Clinical Presentation | Treatment | Follow-up | Fusion | Additional features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J Pouchot 19882 | 11 | 25–69 yrs (40.90) | 7 M 4 F |

1 wk to 13 mo. | All U/L, RT 5 LT 6 MC buttock pain on the affected side. Radicular pain in the lower back 7 cases Tc 99 Scan uptake (10 cases) |

Pathology or bacteriology diagnosis only in 9 cases Arthrodesis in one case. 12–18 mo ATD |

Excellent out come in all | Healed in all | Pul Tb 4 cases, Tb spine 2 cases. |

|

| Osman AA and Govinder S 19953 | 14 | - | - | - | - | Low back pain buttock pain 11 patient demineralization, hazineness and erosion 3 patients erosion with sclerosis |

2 patient abscess drainage 1 arthrodesis 18 Month ATD in all |

18 months to 4.5 year 10 patients asymptomatic; 4 patients mild discomfort remained |

- | Concomitant chest and spine TB |

| Kim et al. 19989 |

16 | 11-65 (32 yrs) | 3 M 13 F |

15–36 mo (8 mo) | Kim types Type 1: 2 Cases Type 2:1 cases Type 3:6 cases Type 4:7 cases |

One case B/L All patient buttock & LBP radicular pain(8 Cases), abscess 8 cases, sinus 2 cases |

Diagnosis confirmed only in 12 patients on pathology. Curettage or curettage and Arthrodesis if instability ATD 18 MO Autologous BG (6 cases) |

2–3.7 yr (avg 2.5 yr) | Bony fusion achieved in 6 patients (18-26 mo); No recurrences |

Active Pul Tb in 5 cases, Tb spine 4 cases. Complication one patient has draining sinus healed with sinus excision |

| Mohammed Benchakroun 200410 | 4 | Mean age 42 | 3 M 1 F |

Mean 14 mo | All Aprin Stage 3 sacroiliitis | 1 case B/L, 2 cases LT, 1 RT Case 1 LBP, buttock pain after prolonged sitting, wt loss Case 2: sciatica and LBP gradual limp, wt loss Case 3: LBP and sciatica Case 4: LBP upon exertion 18 mo, difficult walking |

Surgical biopsy in all ATD in all Case 1, 3, 4 only 6 mo |

Case 2 excellent 1 year later | Pos family history in case 2 Mild pain upon exertion was the only residual symptom |

|

| R J S Ramlakan 200711 | 15 | 15–60 yrs (mean: 27 yrs) | 13 F 2 M |

Range: 11 wk–39 wk (Mean: 18 wk). | 14 U/L, 1 B/L, Persistent LBP and difficult walking Loss of weight appetite and night sweats Bone scans (Tc 99): increased uptake X rays: jsw, joint margins sclerosis and periarticular osteopaenia CT scan: JSW, margins sclerosis, sequestra |

AFB: 9 cases open biopsy and Joint curettage Through PA Patients mobilised on crutches and ATD for 18 mo. |

3–10 years (mean: 5 years). | Bony healing radiologically evident at 2 yr | kk | |

| Ahmed et al. 201312 | 5 | 42.5 | M | fistula left side |

Debridement and fusion Posterior Bone graft and screws Rifampicin? isoniazid |

25 mo Outcome: good |

Pulmonary tuberculosis, epididymitis | |||

| 42.4 | F | Fistula Left, history of Multiple curettage operations before 6 months | Debridement and sequestrectomy, Posterior graft: None Rifampicin ? isoniazid (12 Mo) |

Lost follow up; out come not available | Spondylodiscitis L5–S1 | |||||

| 56 | M | Fistula right Multiple operations in SIJ | Debridement Posterior/posteriorb None GRAFT Rifampicin ? isoniazid 6Mo |

6 Mo; outcome: Poor | Psoas abscess | |||||

| 61.4 | F | Back pain Right Seven operations in SIJ before 30 years |

Debridement Posterior None Ciprofloxacin (4 Mo), ethambutol ? rifampicin ? isoniazid ? pyrazinamide (6 Mo) | 86 Mo; Excellent out come | ||||||

| 52.8 | M | Bilateral Local pain | Debridement and fusion Posterior Bone graft Nitrofurantoin ? rifampicin ? isoniazid (6 Mo) | 9 Mo; Poor out come | Spondylodiscitis L5–S1, psoas abscess, sacral decubitus ulcer | |||||

| Gao 201113 | 15 | 17–64 yrs; mean 33.8 | 7 M 8F |

4–23 mo, mean (10.7 mo) Classified according to Kim Types |

Group A: 5 cases Group B 10 cases |

All U/L; RT 11 LT side Buttock pain and/or LBP, sciatica 4 cases, palpable mass or visible cutaneous fistulas 10 cases |

5 cases Group A Chemotherapy only Group B 10 cases Chemo and joint and sinus debridement surgery. |

30–87 mo (mean, 54 mo) | History of Corticosteroids use. pulmonary TB (two active and three old), old spine Tb in two and epididymis TB in one case | |

| PRAKESH J 201414 | 35 | 22–55 yr (mean: 27 yR) | 21 M 14F |

7 weeks–22 weeks (mean: 10 weeks) | Kim type 6 type 1, 8 type 2, 7 type 3, 2 type 4 |

3 case B/L; 32U/L Persistent low back pain and difficulty with walking |

ATD in all; surgical debridement in 9 patients | 2 years (range 2–6 years | 60% of patients bony ankylosis | 13 patients history of TB contact 4 patients MDR TB; Past history PULTB 9, Potts spine 2, abdominal Koch's 3; incomplete DOTS 3; 4 tuberculosis in other region |

| LUO 201515 | 12 | 32.8 yr (range, 21–63 yr) | 5 M 7F |

12.41 ± 4.36 months (range, 9–24 months) | 1 case B/L, 11 cases U/L; persistent buttock or low back pain, a chronic sinus tract, and difficulty walking n all patients. | NPWT for an average of 18.33 ± 6.97 days (range, 14–35 days) with ATD | 37.1 months | Bony fusion in 5 patients, and fibrous ankylosis in 7; healed in all | Recurrent TB of SIJ in one; Active TB in 2; Spine TB in 2; Intestinal TB in1 2 patients MDR TB |

|

| Zhu et al. 201716 | 17 | 8 M 9 F |

18 to 57 Avg: 30.5 |

7 type II cases, 4 type III cases and 6 type IV cases | 16.2 wk, Range: 6 wk to 15 mo | All cases U/L MC presentation LBP and buttock pain, difficulty walking unable to ear weight (4 Cases), Sciatica (5 cases) palpable inguinal mass (2 cases) |

11 type A: POWFD, BG and JF; 4 type B: anterior abscess curettage before POWFD and JF; 2 type C: POWFD, JF and one-stage posterior lumbar focal lesion clearance, interbody fusion and IF. |

Avg. follow-up 36 mo Range: (26–45 mo) |

Bone fusion early on CT at 3 mo PO. All patients had solid joint fusion within 12 mo No complications or recurrence occurred. |

Pul TB in 4 cases |

Abbreviations: M: male; F: female; Yr: Year: Mo month; wk week: MC: most common; U/L: Unilateral; B/L bilateral; Avg. Average; PD posterior decompression; PO: postoperatively; CT scan: Computed Tomography scan; USG MRI, POWFD: posterior open-window focal debridement; Pul TB: Pulmonary Tuberculosis; BG: bone graft; JF: joint fusion; IF: internal fixation; Pa: posterior approach; SIJ: sacroiliac joint; JSw: Joint space widening; LBP: low back pain; Pos: positive; RT: Right; Left: LT; NPWT: negative pressure wound therapy; DOTS.

2. Anatomic correlation, route, site, and spread of SIJ TB infection

The articular part of sacroiliac joint is composed of hyaline cartilage; lined by synovial membrane and therefore it's prone to tuberculous infection like any other synovial joint. In an early stage, pathologic changes are mostly constrained to the synovium and articular cartilage. In the late stage of the disease, the infection can spread to surrounding regions and track along anatomic planes. A proximity to the lumbar spine and the deep-seated nature of the SIJ leads an unsuspecting clinician to initially treat SIJ TB as a spinal pathology. The commonest mode of inoculation of the SIJ is by hematogenous dissemination from a primary focus of infection usually the lungs. The hematogenous inoculation of the SI joint can happen through the pelvic and paravertebral venous plexus of Batson.17,18 Contiguous spread is usually from the lumbar spine, along with the psoas muscle.19 Unlike ankylosis spondylitis, SIJ TB is usually unilateral. However, in about 6% of instances, bilateral affection can be seen,20 leading to diagnostic dilemma and misdiagnosis.14 The simultaneous involvement of SI joint and pubic symphysis leads to subluxation, disruption of the SI joint on the same side with vertical migration of the left hemipelvis upward. Due to gravity and anatomical features of the SI joint, it may present as an abscess in the gluteal region or as distant ‘sinuses or ‘fistulae’. Gao et al. found 60% of their patients with SIJ TB had other sites affected, such as the lung, epididymis, lumbar, and greater trochanter region.13

3. Clinical features of SIJ TB

3.1. Clinical presentation

The onset is usually insidious. Pain may be dull and continuous and can awake the patient at night, and they find it difficult to bear weight on the affected side; many have difficulty walking and prolonged sitting. The SIJ TB may also be asymptomatic and detected incidentally as a part of multifocal disease.21 Irritation of nerve roots by the disease process and iliopsoas muscle abscess can cause leg pain in the sciatic nerve distribution, presenting as sciatica.22,23

3.2. Clinical assessment

There is often an antalgic gait, with local tenderness over the affected SI joint. Various stress and distraction tests for diagnosing pathology of SI are positive. The sensitivity and specificity of these tests in diagnosing the SI joint pathology varies from 85% to 94% and 78-79%, respectively.24,25

3.3. Clinical diagnosis

The diagnosis of SIJ TB is often delayed due to nonspecific symptoms. The pain may be poorly localized and point towards a pathology at the spine, hip, and other sacral areas.26 SIJ TB sacroiliitis may be mistaken for other causes of low back pain, such as disc diseases, spondylosis, spondyloarthropathies, pyogenic infections, sacroiliac joint dysfunction. Constitutional symptoms such as fatigue, weight loss, and anorexia may also be present.14,15

4. Investigations

-

A)Laboratory Investigations: The gold standard for diagnosing SI joint TB is by identification on culture and histopathological confirmation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacilli.

-

a.Complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-Reactive Protein (CRP) are non-specific tests for diagnosing SI joint TB.

-

b.A definitive diagnosis of SI joint TB requires confirmation with a microbiological identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacilli and/or histopathological sample of involved tissue. As the SI joint is deeply placed, a Computed tomography (CT)-guided, Ultrasound (US) guided biopsy or open biopsy from the joint or synovial membrane can be undertaken for diagnosis. Pouchot et al. used needle biopsy to obtain tissue and noted a success rate of 81.8%.2 However, an open biopsy may be needed when the aspirate yields no growth.14

-

c.Open Biopsy: A high yield can be obtained from an open biopsy, resulting in faster bone healing.15 Kim et al. reported that a pathologic diagnosis could be made only in 75% of their cases.15 Ramlakan and Govender yielded a pathologic diagnosis of Tuberculosis in 88% of patients using open biopsy through posterior approach.11

-

d.Microbiological examination includes identification of acid-fast bacillus (AFB) and mycobacterial culture on Lowenstein-Jensen (LJ) culture medium. However, the yield and culture growth is variable. Ramlakan and Govender were able to culture in 52% cases, whereas Luo et al. in 50% and Prakash et al. in 8% cases only.11,14,15

-

e.Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in synovial tissue or curette material allows amplification of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome and increasingly being used for diagnosis.7

- f.

-

a.

-

B)Imaging modalities for SIJ TB

-

a.Plain Radiographs: Plain Radiographs in the initial stages may reveal haziness or loss of articular margins but later, as the disease progresses, joint widening, irregularity of articular surfaces and subchondral erosion is seen. (Fig. 1). If the disease process is halted (by treatment), narrowing of the joint space and marginal sclerosis is visible. However, if the disease progresses further, the erosive margins become distinct, and cavitation develops. Kim et al. have suggested a clinico-radiological classification of SIJ TB to guide treatment.9

-

b.Computed Tomography (CT) - CT demonstrates joint space widening, sequestrate and calcification more clearly than radiographs. Bony destruction, sclerosis and cavitation of the sacrum and fusion of the joint are better seen on CT.

-

c.Ultrasound (US): US helps to locate the intrapelvic abscess and psoas abscess associated with SIJ TB and may guide diagnostic aspiration.28

-

d.Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)- MRI has been shown to be more sensitive than CT in early diagnosis and has superior ability to evaluate the integrity of the SIJ cartilage.29 In the early stages of the disease, capsular distention is evident. Peri articular bone-marrow edema in the sacrum or ilium or both and soft tissue edema, joint space enlargement, joint effusion, small intraosseous abscesses, cold abscesses, destruction of iliac and sacral bones and sinus tracts are seen easily on MRI and these point towards infective pathology (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).30 Contrast MRI with Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted imaging shows typical peripheral rim enhancement of TB cold abscesses with central necrosis. It is difficult to differentiate pyogenic sacroiliitis from tuberculous sacroiliitis on MRI however features such as pre-existing osteomyelitis in ilium, wide joint space points towards the diagnosis of TB. Further, TB sacroiliitis will have thin, enhancing rim in comparison to the thick and irregular enhancing rim of pyogenic abscess.31 MRI findings of periarticular muscle edema, thick capsulitis, extracapsular fluid collections and large bone erosion reliably differentiate infectious sacroiliitis from unilateral sacroiliitis associated with spondyloarthritis. The presence of iliac-dominant bone marrow edema and joint space enhancement supports the diagnosis of spondyloarthritis.32

-

e.Isotope bone scanning (IBS): IBS is a helpful tool for diagnosis of sacroiliitis when the diagnosis is not clear with other modalities. Technetium-99 m methylene diphosphonate (Tc-99 m MDP) bone scintigraphy shows intense tracer uptake however can be non-specific. To increase specificity, newer scintigraphic techniques have been investigated. Single photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography (SPECT/CT) demonstrates a widened right SI joint with increased uptake. FDG Positron Emission Tomography (FDG-PET Scan) may be more sensitive, especially at early stages of inflammation due to physiological basis of the technique and improve diagnostic accuracy.21,33

-

a.

-

C)Clinico-Radiological classification for SIJ TB

- i)

- ii)

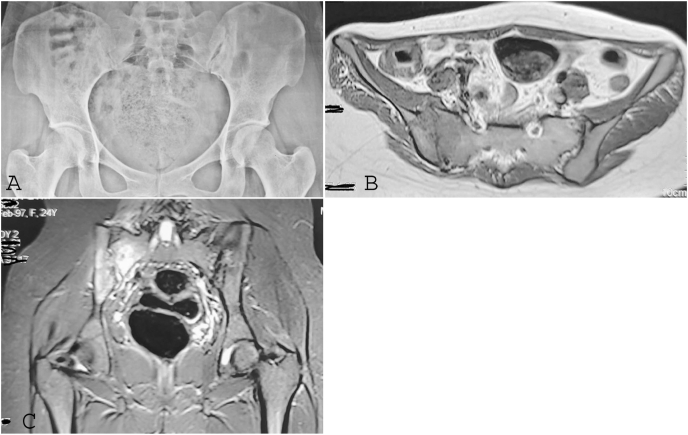

Fig. 1.

a: AP radiograph (a) showing osteopenia and loss of indistinct right SIJ Fig. 1b and c: Axial T1(b) and STIR coronal (c) showing right infective sacroiliitis.

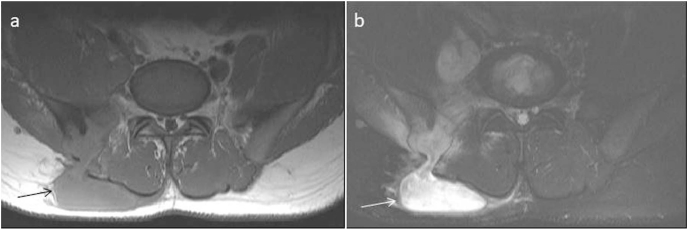

Fig. 2.

Coronal T2FS (a,b) and axial T1(c) showing right infective sacroiliitis with large collection (white arrow).

Fig. 3.

Axial T1(a) and T2FS(b) showing right infective sacroiliitis with large collection.

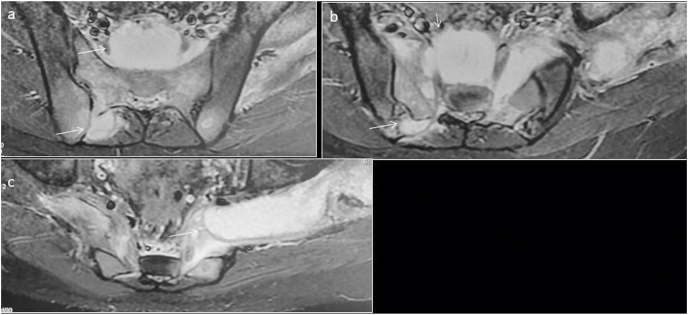

Fig. 4.

Axial T2FS (a,b,c) showing bilateral infective sacroiliitis with large presacral, posterior collection(arrows) tracking into the left sciatic notch.

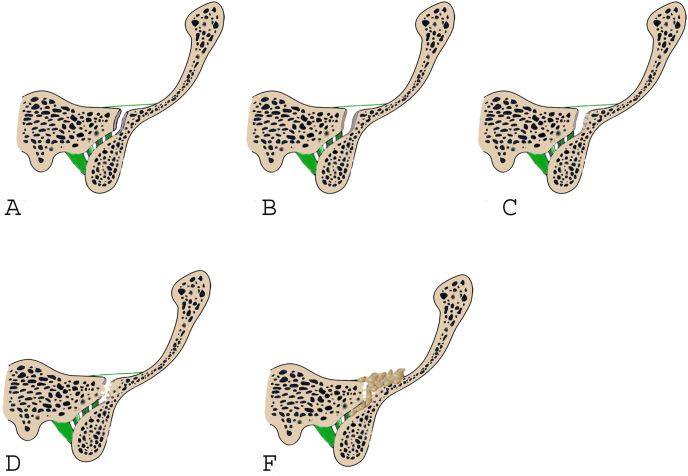

Fig. 5.

Graphical representation showing Kim classification normal SI joint (A); Joint space widening and Blurred joint margin Type 1 (B); Erosions Type 2 (C); Severe joint destruction with cyst formation and marginal sclerosis Type 3 (D); SI joint lesion with abscess or with involvement of vertebra Type 4 (F).

Fig. 6.

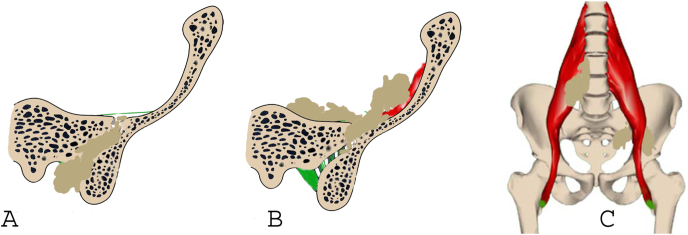

Graphical representation of Zhu et al. Severe joint destruction, with or without a posterior abscess of SI joint, Type A (Kim type 2) (A); Severe joint destruction with an anterior abscess of sacroiliac joint, with or without a posterior abscess, Type B (Kim type 3) (B); Severe joint destruction with spinal tuberculosis, Type C (Kim type 4) (C).

5. Treatment strategies in the management of SI joint tuberculosis

The main objectives of treatment of SIJ TB are immediate relief of the symptoms, prevention of development of complications and extermination of the infection. The mainstay of conservative treatment is an appropriate Anti- tubercular therapy (ATT) regime. Additional non-operative and operative management can be undertaken depending on the stage of the disease.

5.1. Non-operative management-

Early detection of SIJ TB disease with conservative treatment can result in complete remission and minimal long-term disability.34 Adjustment of the dosages of immunosuppressant's, bed rest, immobilization in cast or braces corset, vitamin D supplementation along with ATT are commonly used supportive measures. Prakash J advised all patients on complete bed rest for initial 3 months. After pain subsided, crutch assisted mobilisation was allowed with lumbosacral corset till healing of disease.13 According to the Kim et al, patients in the classification Type 1 and Type 2 can be treated with ATT alone whilst those in Type 3 and Type 4 group probably need surgery along with ATT.9 Only 33.3% of patient in Gao et al study were treated with standard ATT alone.13 The optimum duration of ATT is unclear and ranges from 9 months to 24 months in various studies. However despite this variation in duration of treatment the overall results remains good.35

5.2. Operative management options and clinical outcomes in literature

Operative procedure may be required in refractory cases, recrudescence, and where diagnostic dilemma exists. Kim et al recommend abscesses should be drained surgically to avoid recurrences.9 Other indication of surgery can be persistence or progression of an abscess despite ATT to prevent spread of the disease and fistula formation.1

-

5.2.1.

Surgical therapy includes debridement of infected joint material, drainage of abscesses, decompression, joint curettage, arthrodesis with or without bone grafts and spinal stabilization in cases of concomitant spinal TB.

-

5.2.2.

Shi opined that the surgical approach should be chosen according to the location and size of abscess and the direction of fistula for SIJ TB. He indicated anterior approach for abscess in iliac fossa or with fistula in buttock; Posterior approach for cases with or without abscess and/or fistula of buttock and combined approach for the cases with large abscess and/or fistula both at iliac fossa and buttock region.36

-

5.2.3.

About 75% of patients in Kim et al study were treated by surgical methods along with ATT. Authors suggest that surgery eradicates pus, granulation and necrotic tissue. They believe surgery improves the effectiveness of ATT by increasing blood flow to surgical site and reduces overall treatment period.9

-

5.2.4.

In about 46.6% of patients in Gao et al. series, debridement and arthrodesis was undertaken. The indication of arthrodesis was an unstable SI Joint due to extensive joint destruction. An additional iliac bone flap was pedicled with gluteus maximus to fill large tuberculous cavity and induce bony fusion.13

-

5.2.5.

Zhu et al have proposed a surgical approach method to treat SIJ TB based on their classification16 (Fig. 5). They suggested that the surgical approach should be chosen according to the location and size of abscess and the direction of fistula. Type A patients were approached with posterior open-window focal debridement, autologous bone graft and joint fusion. They believe, posterior approach offers appropriate exposure of SI joint without risk of injury to neurovascular structures. Type B patients were treated first with anterior abscess curettage in supine then posterior open-window focal debridement and joint fusion in prone position. Further the Type C patients were operated with posterior open-window focal debridement, joint fusion and one-stage posterior lumbar focal lesion clearance, interbody fusion and internal fixation.

-

5.2.6.

Use of Bone grafting: While Zhu et al used bone graft in all patients to achieve union, others have not routinely used it after joint curettage and debridement.9,11,13,16

-

5.2.7.

Use of OsteoSet:Li et al successfully treated SIJ TB by using bone graft interbody fusion along with rifampicin loaded OsteoSet after joint debridement. Bone union was observed at 10.5 months on average in about 90% patients.37

-

5.2.8.

Minimally Invasive surgery: A minimally invasive retroperitoneoscopic technique has been used by Chandrasekhar et al in 2 patients of anterior sacroiliac joint tuberculosis. This technique helps to avoid sacral nerve roots injury and posterior cortex break with an advantage of providing early patient mobilization.38

-

5.2.9.

Role of Negative Pressure Wound Therapy (NPWT):Luo et al. have successfully used NPWT therapy in all patients to treat chronic sinuses in SIJ TB. They concluded that the use of NPWT can decrease the mycobacterial load by removing pus, necrotic tissue and promote the proliferation of granulation tissue in the sinus tract.15

-

5.2.10.

Role of Immobilization after surgery: Immobilization by bed rest and/or spica cast/orthosis/lumbosacral brace is recommended for patients with severe pain or after operative management by some authors.13,14

6. Monitoring response to therapy

Clinical response is evaluated by resolution of the clinical symptoms and signs after commencement of ATT or after the surgery. A painless SI joint with full functional recovery, appearance of sclerosis of the joint margin or bony or solid fibrous fusion of the joint is indicative of healed disease. Inflammatory markers such as C - reactive protein (CRP) and ESR are nonspecific but have a role in evaluation of response to therapy. Zhu et al. suggest ESR usually returns to normal level, 3 months after start of treatment in most patients. However, despite appropriate therapy, radiological findings may take time to resolve and sometimes even progression may be observed.22 The onset of bone union can be variable.13 Bone union may be seen as early as 3 months after surgery on CT, however, can take up to 6-24 months after initial diagnosis and treatment.9,11,15 Extended follow-up of these patients after completion of treatment is recommended to recognize early recurrence and long-term outcome of therapy.

7. Prognostic factors in the outcome of SIJ TB

A delayed diagnosis, presence of multiple abscesses, instability of SI joint, concomitant involvement of lumbar spine, presence of sinus tracts, residual abscesses after surgery are poor prognostic factors and can affect clinical outcome.9,14,16

8. Conclusion

SIJ TB is an uncommon site for Mycobacterium Tuberculosis infection. . Diagnosis of SI joint TB is often delayed in early stages due to its indolent nature and is commonly confused with other spinal conditions. A high index of suspicion especially in patients from endemic TB regions should initiate early investigations and complementary imaging to confirm diagnosis. Once diagnosis of SIJ TB is established, appropriate and timely introduction of ATT regime with surgical intervention in patients not responding to conservative therapy will allow good functional outcome.

Author statements

VKJ, KPI involved in Conceptualization, literature search, manuscript writing and editing. VKJ, KPI in literature search, methodology, data curation, manuscript review, and editing. RV, RB supervised overall submission and approved the final draft. All authors read and agreed the final draft submitted.

Funding statement

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Statement of ethics

The current submitted article is not a clinical study and does not involve any patients.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Contributor Information

Vijay Kumar Jain, Email: drvijayortho@gmail.com.

Karthikeyan P. Iyengar, Email: kartikp31@hotmail.com.

Rajesh Botchu, Email: drbrajesh@yahoo.com.

Raju Vaishya, Email: raju.vaishya@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Papadopoulos ECh, Papagelopoulos P.J., Savvidou O.D., Falagas M.E., Sapkas G.S., Fragkiadakis E.G. Tuberculous sacroiliitis. Orthopedics. 2003 Jun;26(6):653–657. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20030601-18. quiz 658-9. PMID: 12817734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pouchot J., Vinceneux P., Barge J., et al. Tuberculosis of the sacroiliac joint: clinical features, outcome, and evaluation of closed needle biopsy in 11 consecutive cases. Am J Med. 1988 Mar;84(3 Pt 2):622–628. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osman A.A., Govender S. Septic sacroiliitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995 Apr;(313):214–219. PMID: 7641483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammoudeh M., Khanjar I. Skeletal tuberculosis mimicking seronegative spondyloarthropathy. Rheumatol Int. 2004 Jan;24(1):50–52. doi: 10.1007/s00296-003-0334-z. Epub 2003 May 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baronio M., Sadia H., Paolacci S., et al. Etiopathogenesis of sacroiliitis: implications for assessment and management. Kor J Pain. 2020 Oct 1;33(4):294–304. doi: 10.3344/kjp.2020.33.4.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Augé B., Toussirot E., Wendling D. Tuberculous rheumatism presenting as spondyloarthropathy. J Rheumatol. 1999 Oct;26(10):2288–2289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu T.J., Chiang W.F., Wu S.T., Lin S.H. Tuberculous sacroiliitis in a renal transplant recipient: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2013 Sep;45(7):2798–2800. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agashe V.M., Rodrigues C., Soman R., et al. Diagnosis and management of osteoarticular tuberculosis: a drastic change in mind set needed-it is not enough to simply diagnose TB. Indian J Orthop. 2020 Jul 25;54(Suppl 1):60–70. doi: 10.1007/s43465-020-00202-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim N.H., Lee H.M., Yoo J.D., Suh J.S. Sacroiliac joint tuberculosis. Classification and treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999 Jan;(358):215–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benchakroun M., El Bardouni A., Zaddoug O., et al. Tuberculous sacroiliitis. Four cases. Joint Bone Spine. 2004 Mar;71(2):150–153. doi: 10.1016/S1297-319X(03)00153-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramlakan R.J., Govender S. Sacroiliac joint tuberculosis. Int Orthop. 2007 Feb;31(1):121–124. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0132-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed H., Siam A.E., Gouda-Mohamed G.M., Boehm H. Surgical treatment of sacroiliac joint infection. J Orthop Traumatol. 2013 Jun;14(2):121–129. doi: 10.1007/s10195-013-0233-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao F., Kong X.H., Tong X.Y., et al. Tuberculous sacroiliitis: a study of the diagnosis, therapy and medium-term results of 15 cases. J Int Med Res. 2011;39(1):321–335. doi: 10.1177/147323001103900135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prakash J. Sacroiliac tuberculosis - a neglected differential in refractory low back pain - our series of 35 patients. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2014 Sep;5(3):146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo X., Tang X., Ma Y., Zhang Y., Fang S. The efficacy of negative pressure wound therapy in treating sacroiliac joint tuberculosis with a chronic sinus tract: a case series. J Orthop Surg Res. 2015 Aug 6;10:120. doi: 10.1186/s13018-015-0250-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu G., Jiang L.Y., Yi Z., et al. Sacroiliac joint tuberculosis: surgical management by posterior open-window focal debridement and joint fusion. BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2017 Nov 29;18(1):504. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1866-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raman R., Dinopoulos H., Giannoudis P.V. Management of pyogenic sacroiliitis: an update. Curr Orthop. 2004;18:321. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garg R.K., Somvanshi D.S. Spinal tuberculosis: a review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34(5):440–454. doi: 10.1179/2045772311Y.0000000023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kramer L., Geib V., Evison J., Altpeter E., Basedow J., Brügger J. Tuberculous sacroiliitis with secondary psoas abscess in an older patient: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2018 Aug 18;12(1):237. doi: 10.1186/s13256-018-1754-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seddon H.J., Strange F.G. Sacroiliac tuberculosis. Br J Surg. 1940;28:193–221. https://epos.myesr.org/poster/esr/ecr2020/C-08321/Results#poster [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albano D., Treglia G., Desenzani P., Bertagna F. Incidental unilateral tuberculous sacroiliitis detected by 18F-FDG PET/CT in a patient with abdominal tuberculosis. Asia Ocean J Nucl Med Biol. 2017;5(2):144–147. doi: 10.22038/aojnmb.2017.8634. Spring. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shields D.W., Robinson P.G. Iliopsoas abscess masquerading as 'sciatica. BMJ Case Rep. 2012 Dec 20;2012 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-007419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen W.S. Chronic sciatica caused by tuberculous sacroiliitis. A case report. Spine. 1995 May 15;20(10):1194–1196. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199505150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laslett M., Aprill C.N., McDonald B., Young S.B. Diagnosis of sacroiliac joint pain: validity of individual provocation tests and composites of tests. Man Ther. 2005 Aug;10(3):207–218. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Wurff P., Buijs E.J., Groen G.J. A multitest regimen of pain provocation tests as an aid to reduce unnecessary minimally invasive sacroiliac joint procedures. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006 Jan;87(1):10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mekhail N., Saweris Y., Sue Mehanny D., Makarova N., Guirguis M., Costandi S. Diagnosis of sacroiliac joint pain: predictive value of three diagnostic clinical tests. Pain Pract. 2020 Sep 23 doi: 10.1111/papr.12950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Unuvar G.K., Kilic A.U., Doganay M. Current therapeutic strategy in osteoarticular brucellosis. North Clin Istanb. 2019 Oct 24;6(4):415–420. doi: 10.14744/nci.2019.05658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bouajina E., Harzallah L., Hachfi W., et al. Sacro-iliites tuberculeuses: à propos de 22 cas [Tuberculous sacro-iliitis: a series of twenty-two cases] Rev Med Interne. 2005 Sep;26(9):690–694. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphey M.D., Wetzel L.H., Bramble J.M., et al. Sacroiliitis: MR imaging findings. Radiology. 1991;180:239–244. doi: 10.1148/radiology.180.1.2052702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akar S., Satoğlu İ.S., Mete B.D., Tosun Ö. Tuberculous sacroiliitis: a cause of bone marrow edema in magnetic resonance imaging. Eur J Rheumatol. 2016 Jun;3(2):93–94. doi: 10.5152/eurjrheum.2015.0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calle E., González L.A., Muñoz C.H., Jaramillo D., Vanegas A., Vásquez G. Tuberculous sacroiliitis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus: a case report and literature review. Lupus. 2018 Jul;27(8):1378–1382. doi: 10.1177/0961203318762594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang Y., Hong S.H., Kim J.Y., et al. Unilateral sacroiliitis: differential diagnosis between infectious sacroiliitis and spondyloarthritis based on MRI findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015 Nov;205(5):1048–1055. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.14217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ozmen O., Gokcek A., Tatci E., Biner I., Akkalyouncu B. Integration of PET/CT in current diagnostic and response evaluation methods in patients with Tuberculosis. Nucl Med Mol Imag. 2014;48(1):75–78. doi: 10.1007/s13139-013-0236-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar S., Jain V.K. Sternoclavicular joint Tuberculosis: a series of conservatively managed sixteen cases. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2020 Jul;11(Suppl 4):S557–S567. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2020.04.026. Epub 2020 May 1. Erratum in: J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2020 Nov-Dec;11(6):1169-1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tuli S.M. 4TH d. Jaypee brothers' publishers private limited; New Delhi: 2010. Tuberculosis of the Skeletal System (Bones, Joints, Spine, and Bursal Sheaths) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi S.S. [Comparison among the surgical approaches to Tuberculosis of sacroiliac joint] Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 1993 Nov;31(11):660–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li S., Zhang H., Zhao D., Liu F., Wang S., Zhao F. [Treating sacroiliac joint tuberculosis with rifampicin-loaded OsteoSet] Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2015 Apr;29(4):406–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chandrashekar S., Kirouchenane A., Thanakumar J.A. An initial report on a new technique: retroperitoneoscopy for the diagnosis of anterior sacroiliac joint pathology. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008 Dec;21(8):585–588. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e31815c6d32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]