Abstract

Backgroud

The 155° Grammont reverse shoulder replacement has a long track record of success, but also a high radiographic notching rate. The increased distance between the scapular pillar and the humeral component theoretically decreases postoperative notching. The glenoid component can be shifted inferiorly relative to the glenoid; however, there also is some concern that shifting the glenoid component too far inferiorly (inferior glenoid component overhang > 3.5 mm) may compromise long-term stability of the glenoid component. This study was conducted to determine if clinical outcomes, scapular notching, and complications vary with more inferior placement of the glenoid component.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data was performed in order to compare radiographic outcomes (notching rate and signs of glenoid loosening or component disassembly) and clinical outcomes (range of motion, Constant score, subjective shoulder value, and complication rate) of all patients who underwent reverse shoulder replacement with the glenosphere positioned either flush with the inferior rim of the glenoid (flush group) or with at least 3.5 mm of inferior overhang (overhang group) at a minimum follow-up of 60 months. Ninety-seven patients ultimately met the inclusion criteria, with 41 patients with flush glenoid component and 56 patients with at least 3.5 mm of inferior overhang.

Results

Average follow-up was 97.8 months. The overhang group had a lower rate of radiographic notching (37% vs. 82.5%, p < 0.05), better clinical outcomes (improvement in Constant score: +40 vs. +32, p = 0.036), and higher subjective shoulder value (79 vs. 69, p = 0.026) than the flush group. No difference in complications between groups was found.

Conclusions

In this study, at least 3.5 mm of inferior glenosphere overhang relative to the inferior rim of the glenoid was associated with the lower notching rate without negative effect on the clinical outcomes in 155° Grammont-style reverse shoulder replacement. Therefore, no increase in complications should be expected when using this surgical technique.

Keywords: Shoulder, Arthroplasty, Range of motion, Scapular notching, Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty

Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) is a safe and effective treatment option for a wide assortment of shoulder pathologies. The Grammont design, with a neck-shaft angle of 155° and a medialized center of rotation, has a long track record in terms of both pain relief, as well as improved range of motion (ROM).1,2) Long-term follow-up has revealed issues, however, with scapular notching and progressively worsening clinical outcomes.3,4,5,6) In an attempt to reduce the notching rate, a variety of implant designs and surgical techniques have been employed. Nyffeler et al.7) placed a 29-mm baseplate precisely at the inferior rim with a 36-mm sphere, which allows an inferior glenoid component overhang (IGO) of 3.5 mm. In theory, by translating the inferior aspect of the glenoid component distally, there should be less impingement of the humeral component with the scapular pillar and, subsequently, less notching. This has been shown in computer and in vitro models,8,9) and more recently some clinical studies have also demonstrated decreased notching with inferior overhang,6,10,11,12,13,14) as well as improved clinical outcomes.15) However, there also is some concern that shifting the glenoid component too far inferiorly (IGO > 3.5 mm) may compromise long-term stability.16,17,18)

The primary goal of this study was to compare mid- to long-term clinical and radiological outcomes of RSA (notching rate and stability based on the presence of radiolucent lines) between patients with flush positioned glenospheres (i.e., the inferior border of the glenosphere at the level of the inferior glenoid rim) and those with an IGO over 3.5 mm. The secondary goal of this study was to evaluate perioperative and postoperative complication rates in both groups. Our hypothesis is that inferiorly overhung glenospheres greater than 3.5 mm would have a lower scapular notching rate, without negatively impacting the clinical outcomes or increasing the complication rates.

METHODS

Institutional Review Board approval of University Institute of Locomotion and Sports (No. 2015-01-RSA results) was granted for this cohort study, and all patients gave informed consent to participate. A retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data was performed.

Study Population

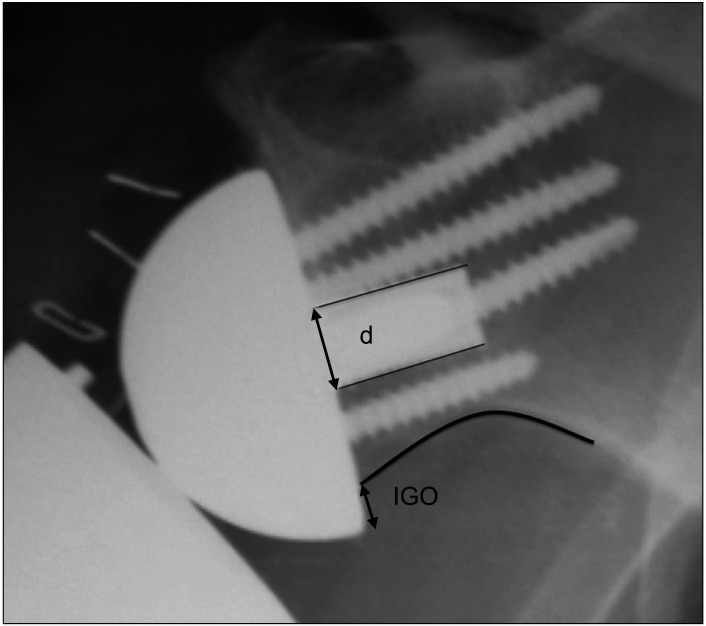

All patients who underwent RSA, performed by a single surgeon (GW) from 1995 through 2010, were eligible for the study. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) primary arthroplasty, (2) placement of the glenosphere in either a flush or an overhung position (IGO > 3.5 mm), (3) follow-up of at least 60 months, (4) full preoperative and postoperative assessment of ROM, Constant score, and subjective shoulder value (SSV), and (5) full set of radiographic images at last follow-up. The glenosphere position was confirmed by assessing the glenosphere relative to the glenoid on anterior-posterior (AP) radiographs taken immediately postoperatively. IGO depends on both the glenosphere type and diameter and the baseplate's positioning and diameter. The IGO was measured on AP radiographs taken immediately after surgery. We measured the distance between the inferior part of the glenoid bone and the inferior part of the glenosphere. Since the diameter of the post at the level of the baseplate is known (8.3 mm for the baseplate used in this study), we used it as a reference to ascertain the true IGO (Fig. 1) using the following formula: IGO×(8.3 / diameter of the post of the baseplate).

Fig. 1. Measurement of inferior glenoid component overhang (IGO) on an anteroposterior view X-ray. d: diameter of the post of the baseplate (8.3 mm).

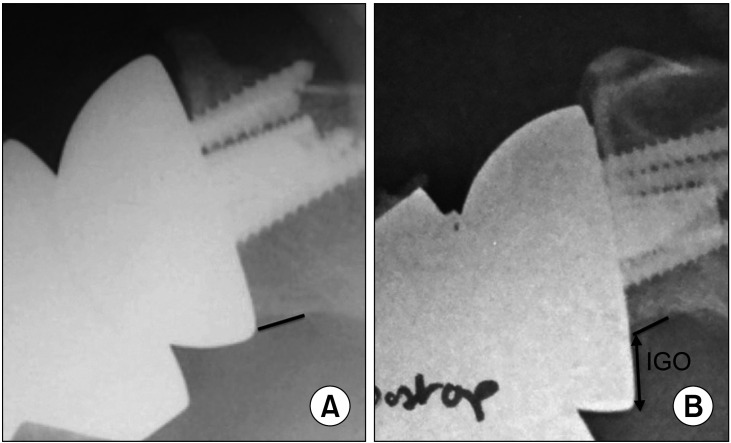

The flush group was composed of patients who presented with a flush glenosphere position defined by the alignment of the inferior border of the glenosphere with the inferior glenoid rim (IGO = 0 mm). The overhang group was composed of the patients who presented with an IGO of at least 3.5 mm (Fig. 2). All X-rays were performed using fluoroscopic guidance at our institution. Measurements were made using GeoGebra Classic software v.6 (Linz, Austria).

Fig. 2. Position of the glenoid component on anteroposterior views. (A) Flush positioning. (B) Overhang positioning (inferior glenoid component overhang [IGO], > 3.5 mm).

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) indications such as revision, fracture sequelae, or tumor, (2) all RSA in which the glenosphere was placed in positions other than flush or overhung (i.e., glenospheres that were higher or in which inferior overhang was between 0 and 3.5 mm), and (3) incomplete clinical and radiographic follow-up. Two patients in the overhang group and 1 patient in the flush group had good immediate postoperative images that confirmed positioning but did not have X-rays available at the last follow-up. These patients were included in the clinical outcome analysis but were excluded from the last radiographic analysis.

Surgical Technique

The senior author (GW) performed all operations. The same Grammont-type RSA implant was used in all cases (Aequalis Reversed II; Tornier, Edina, MN, USA). A deltopectoral approach was used; 2 cm of the pectoralis major tendon was released and the subscapularis tendon (if intact) was tenotomised at the anatomical neck. The humeral head was cut with 0° to 20° to match the natural retroversion. The inferior aspect of the glenoid was exposed fully and the glenoid baseplate was placed as inferiorly as possible. The glenoid base plate was placed in approximately 10° of inferior tilt. Either three or four screws were used for fixation, depending on the available glenoid bone stock and the surgeon's preference. A 36-mm diameter glenosphere or a 42-mm diameter glenosphere was inserted. A standard or eccentric glenosphere was then fixed to the baseplate provided by the manufacturer (Tornier). The choice between the 36-mm and 42-mm glenospheres and the eccentric or standard sphere was not randomized but based on the surgeon's preference. The humeral component was then placed in the standard fashion. In all cases, an attempt was made to repair the subscapularis tendon via transosseous sutures. A soft-tissue biceps tenodesis was also performed when the tendon was still present.

Assessment Criteria

The ROM and Constant score19) were measured preoperatively and at the last follow-up, while the SSV20) was determined at the last follow-up in the two groups. Scapular notching was graded according to the Sirveaux classification21) at the last follow-up on an AP view of the glenohumeral joint. We also assessed the radiographs for radiolucent lines around the post, screws, or behind the baseplate and for any other obvious signs of glenoid loosening or component disassembly. Perioperative (fractures) and postoperative complications (neurological complications, fractures, dislocations, infection, etc.) were also evaluated.

Statistical Analysis

Clinical outcomes were compared statistically using the paired Student t-test for quantitative data and chi-square test for qualitative data. Bivariate conditional logistic regression was used to assess scapular notching. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. All statistics were performed by a professional biostatistician from a company (HC) that specializes in medical statistical analysis.

RESULTS

A total of 105 patients ultimately met the inclusion criteria. Forty-one patients were included in the flush group. Sixty-one patients were originally selected for the overhang group, but five were excluded because of poor quality postoperative X-rays, resulting in 56 patients in the overhang group. One patient in the flush group and two patients in the overhang group did not have their radiographs available at the last follow-up. These patients were included in the clinical outcome analysis, but were excluded from the last radiographic analysis.

There were no significant differences in terms of preoperative demographics such as age, sex, and surgical indication (Table 1). The mean follow-up was 114 months in the flush group and 92 months in the overhang group (p = 0.002). No statistical difference was found between groups regarding preoperative ROM and Constant scores (Table 1) . Due to lack of data, BMI was not compared between the two groups. Six patients in the flush group and 2 in the overhang group did not have a preoperative computed tomography scan. For the other patients, analysis of preoperative fatty infiltration of the infraspinatus found 74% stage three or four in the overhang group versus 52% in the flush group (p = 0.03). In the flush group, the teres minor was normal in 82% versus 85% in the overhang group (p = 0.464).

Table 1. Demographics and Preoperative Data.

| Variable | Overhang group (n = 56) | Flush group (n = 41) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 74 (62 to 85) | 74 (55 to 85) | 0.924 | |

| Sex (female : male) | 41 : 15 (73 : 27) | 33 : 8 (80 : 20) | 0.405 | |

| Indication | 0.131 | |||

| Cuff tear arthropathy | 17 | 20 | ||

| Osteoarthritis | 19 | 8 | ||

| Massive cuff tear | 16 | 10 | ||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 3 | 0 | ||

| Instability arthroplasty | 1 | 3 | ||

| ROM | ||||

| aAF (°) | 85 (30 to 170) | 90 (20 to 180) | 0.817 | |

| aER1 (°) | 15 (–40 to 90) | 10 (–45 to 80) | 0.525 | |

| aIR1 | 4.5 (0 to 10) | 3.5 (0 to 12) | 0.041 | |

| Constant score | ||||

| Total | 31 (9 to 63) | 30 (9 to 55) | 0.773 | |

| Pain | 5 (0 to 15) | 4 (0 to 12) | 0.041 | |

| Activity | 7 (2 to 18) | 7 (2 to 13) | 0.813 | |

| Mobility | 16 (2 to 36) | 15 (0 to 40) | 0.975 | |

Values are presented as mean (range), number (%), or absolute number.

ROM: range of motion, aAF: active anterior flexion, aER1: active external rotation with elbow against the body, aIR1: internal rotation.

The clinical outcomes at the last follow-up are summarized in Table 2. While the results seemed better in the overhang group, the improvement in anterior flexion (+65° vs. +45°, p = 0.059) and rotation were not significantly better than that in the flush group. The improvement in functional outcome was higher in the overhang group (Constant score: +40 vs. +32, p = 0.036), especially in the activity subset of the Constant score (p = 0.009). The SSV was also higher in the overhang group than in the flush group (79 vs. 69, p = 0.026).

Table 2. Postoperative Range of Motion and Functional Outcomes.

| Variable | Overhang group | Flush group | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROM | ||||

| aAF (°) | +65 (–20 to +140) | +45 (–70 to +130) | 0.059 | |

| aER1 (°) | +10 (–80 to +70) | +5 (–60 to +50) | 0.149 | |

| aIR1 | +2 (–4 to +8) | +2 (–4 to +8) | 0.384 | |

| Constant score | ||||

| Total | +40 (–9 to +66) | +32 (–3 to +59) | 0.036* | |

| Pain | +8 (–2 to +14) | +8 (–2 to +14) | 0.895 | |

| Activity | +10 (–2 to +18) | +8 (–2 to +16) | 0.009* | |

| Mobility | +16 (0 to +32) | +13 (–12 to +30) | 0.101 | |

| Strength | +5 (–2 to +14) | +3 (–8 to +10) | 0.152 | |

| SSV | 79 | 69 | 0.026* | |

Values are presented as mean (range).

ROM: range of motion, aAF: active anterior flexion, aER1: active external rotation with elbow against the body, aIR1: internal rotation, SSV: subjective shoulder value.

*Statistically significant, p < 0.05.

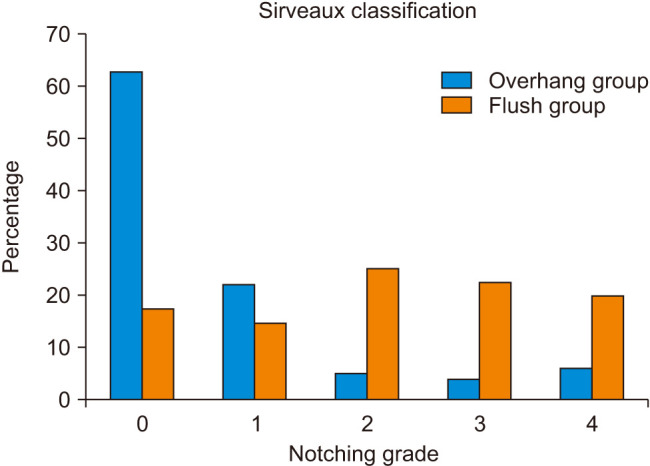

The analysis of immediate postoperative X-rays in the overhang group found a mean IGO of 8 mm (range, 4–16 mm). The incidence of notching at the last assessment is reported in Fig. 3. Scapular notching was found in 37% of cases in the overhang group versus 82.5% of cases in the flush group (p < 0.05). The severity of notching between the two groups was also significantly different (p < 0.05).

Fig. 3. Notching grade relative to the baseplate position (Sirveaux classification).23).

In the overhang group, there was no correlation between the IGO magnitude and both the rate (R2 = 0.008) and the severity of notching (R2 = 0.056) (Table 3). When analyzing for radiolucent lines (Table 4), we found no significant difference between the two groups as well.

Table 3. Notching Severity.

| Notching grade | Mean IGO (mm) | R 2 |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 8 | 0.056 |

| 1 | 8 | |

| 2 | 8 | |

| 3 | 6 | |

| 4 | 10 |

IGO: inferior glenosphere component overhang.

Table 4. Presence of Osteolysis and Radiolucent Lines.

| Variable | Overhang group | Flush group | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiolucent line | ||||

| Around screw | 1 (1.5) | 2 (3) | 0.32 | |

| Below baseplate | 5 (7.5) | 10 (15) | 0.61 | |

| Around post | 1 (1.5) | 2 (3) | 0.32 | |

Values are presented as number (%).

Complications occurred in 22% of cases in the flush group and in 18% of cases in the overhang group (Table 5). In the overhang group, 5 patients sustained perioperative fractures, including 3 greater tuberosity fractures, 1 glenoid fracture, and 1 coracoid fracture. Three patients had postoperative neurological complications including 1 cubital tunnel syndrome, 1 partial axillary nerve palsy, and 1 brachial plexus palsy. We identified only 1 scapular spine fracture, which presented 6 months after surgery. One patient suffered infection and underwent revision and reimplantation. In the flush group, 1 patient had perioperative glenoid fracture. There were 4 neurological complications, including 3 cases of cubital tunnel syndromes and 1 partial axillary nerve palsy. Three patients developed scapular spine fractures, of which 2 appeared before 6 months postoperatively and 1 after 6 months. There was 1 case of glenosphere dissociation from the baseplate and 1 case of dislocation. There were no infections. In the flush group, only 1 patient underwent revision surgery (for glenosphere dissociation). The dislocation was managed by closed reduction.

Table 5. Complications.

| Variable | Overhang glenosphere | Flush glenosphere |

|---|---|---|

| Perioperative fracture | 5 (9): 3 greater tuberosity fractures, 1 glenoid fracture, 1 coracoid fracture | 1 (2): glenoid fracture |

| Neurological complication | 3 (5): 1 axillary, 1 cubital nerve, 1 plexus | 4 (10): 3 cubital, 1 axillary |

| Spine or acromial fracture | 1 (2) | 3 (7) |

| Glenoid disassembly | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Dislocation | 0 | 0 |

| Infection | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Total | 10 (18) | 9 (22) |

Values are presented as number (%).

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study is that an IGO of at least 3.5 mm relative to the inferior rim of the glenoid was associated with a lower notching rate and severity, higher Constant score, and SSV without negatively affecting the complication rate in RSA.

RSA is an effective surgery with an expanding list of indications, but concerns remain about long-term clinical deterioration and scapular notching.1,2,3,4,5) Many factors have been associated with the development of scapular notching: prosthetic design,22) surgical approach,23,24) positioning of the glenosphere too superiorly and/or with superior tilt,5,21,22,25) preoperative diagnosis,23) and anatomical glenosphere variations with short neck lengths resulting in superior glenoid erosion.26) Posterior impingement—in which the physical contact occurs posteriorly as opposed to inferior to the glenoid—has gained recognition as a cause of notching.27) The clinical effects of scapular notching are still under debate, though some studies show worse clinical outcomes with increased notching.5,28) In addition, Roche et al.29) showed that scapular notching may affect glenoid fixation. Various strategies have thus been employed to decrease notching rates. Recent design innovations have attempted to reduce notching by lateralizing the humerus with 135° or 145° angled designs3,9) or by lateralizing the glenosphere component.30,31) These design options are promising, but their long-term outcomes are still to be observed. The original 155° Grammont implant remains a viable option with the longest clinical follow-up, thus we feel it is clinically relevant to determine the optimal glenosphere position with this design.

Several studies have demonstrated lower notching rates with inferiorly positioned glenospheres in the short-4,15,29) or mid-term follow-up evaluation.14) While notching tends to occur early in the postoperative period,4) there is a concern that it progresses over time. Our data provide the longest-term follow-up to date comparing flush and inferiorly offset glenospheres in the Grammont style RSA implant. Similarly, compared to previous authors, we showed a lower notching rate, which means this holds true for long-term results as well. The patients with an inferiorly translated glenosphere had a significantly lower rate of scapular notching (37%) than those with the glenosphere aligned with the inferior glenoid rim (82.5%). The notching observed in the overhang group was also more commonly stage I, whereas it was more severe in the flush group. So, having an IGO of at least 3.5 mm decreased significantly both the frequency and severity of notching.

As Laderman et al.,27) we believe that notching represents a spectrum of impingement, which begins on the inferior part of the scapular pillar and spreads to the posterior part of the pillar. Although our analysis of the IGO showed that an IGO greater than 3.5 mm was associated with a lower notching rate (p < 0.05), it should be noted that notching still occurred occasionally despite the inferiorly translated glenospheres. So, even though the fact that a glenoid component translated inferiorly decreases notching, this one parameter alone is not enough to prevent notching. In these cases, continued posterior impingement could explain the persistence of notching. To increase the distance between the humeral component and posterior part of scapula pillar effectively, lateralization of the glenoid component could be another option to help surgeons deal with posterior impingement. This requires additional studies.

Our findings related to clinical outcomes should be interpreted carefully while keeping in mind the difference in the notching rate between the two groups. Patients in whom the glenospheres were translated inferiorly to the glenoid rim position did not have inferior Constant scores and SSV scores as compared to the flush group. Li et al.10) reported similar findings regarding notching and IGO, but they did not demonstrate any difference in terms of ROM or clinical outcomes in patients with 147° design implants. Poon et al.11) similarly showed decreased notching with increased inferior offset, and no notching at all in patients with at least 3.5 mm of inferior overhang, but no differences in clinical outcomes. In contrast, De Biase et al.15) found improved clinical outcomes in the short term (2 years). Our data revealed that in addition to improved radiographic results, there are also better clinical results with the inferiorly translated glenospheres but these differences were not significant and could be explained by either the inferior overhang or the lower notching rate.3,4)

The complication rates did not differ significantly between the two cohorts. Lengthening of the arm is associated with scapular spine fractures as well as neurologic injury.32) Furthermore, several in vitro studies have suggested that lowering the glenosphere may compromise stability. Gutierrez et al.17) showed that a rocking horse effect could occur without support of the inferior glenosphere—as occurs with inferior eccentric positioning—which could lead to glenoid component loosening. Nigro et al.33) similarly mentioned the importance of the contact between the bone and glenoid component to prevent micromotion and subsequent loosening. In our study, the flush group had a higher complication rate although the difference was not statistically significant. Of note, glenoid loosening did not occur linically with the inferiorly translated glenospheres, despite the findings from previous in vitro studies.

Our study has several limitations, starting with those inherent to a retrospective design. Although the aim was to place the baseplate in 10° of inferior tilt and the glenospheres in their designated (flush or inferiorly translated glenospheres) positions, prosthesis implantation was based on subjective estimates during surgery as patient-specific instrumentation was not available at this point. However, we did assess the glenosphere positions on postoperative views to confirm appropriate placement as best as possible. Lastly, some differences in clinical outcomes are statistically significant, but may not meet the threshold of being clinically significant. Both the BMI and the fatty infiltration data were incomplete, thus did not allow a reliable comparison between our two groups. The other data were similar between groups (age, sex, and indication). Average follow-up was different between the two groups by 1 year. In the mid-term follow-up, we did not think that this difference could influence our clinical or radiological results. The strengths of our study are the long follow-up with pre- and postoperative clinical and radiographic data, as well as the relatively large number of patients compared with previous studies.

At least 3.5 mm of IGO relative to the inferior rim of the glenoid was associated with a lower notching rate without negatively affecting the clinical outcomes, when employing a 155° Grammont-style reverse shoulder replacement. Therefore, no increase in complications should be expected when using this surgical technique.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Hugo Caillou, senior consultant, biostatistician, Capionis, for the data analyses.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Boileau P, Watkinson DJ, Hatzidakis AM, Balg F. Grammont reverse prosthesis: design, rationale, and biomechanics. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(1 Suppl S):147S–161S. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bacle G, Nove-Josserand L, Garaud P, Walch G. Long-term outcomes of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a follow-up of a previous study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(6):454–461. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.00223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erickson BJ, Frank RM, Harris JD, Mall N, Romeo AA. The influence of humeral head inclination in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(6):988–993. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Werner CM, Steinmann PA, Gilbart M, Gerber C. Treatment of painful pseudoparesis due to irreparable rotator cuff dysfunction with the Delta III reverse-ball-and-socket total shoulder prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(7):1476–1486. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simovitch RW, Zumstein MA, Lohri E, Helmy N, Gerber C. Predictors of scapular notching in patients managed with the Delta III reverse total shoulder replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(3):588–600. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhee SM, Lee JD, Park YB, Yoo JC, Oh JH. Prognostic radiological factors affecting clinical outcomes of reverse shoulder arthroplasty in the Korean population. Clin Orthop Surg. 2019;11(1):112–119. doi: 10.4055/cios.2019.11.1.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nyffeler RW, Werner CM, Gerber C. Biomechanical relevance of glenoid component positioning in the reverse Delta III total shoulder prosthesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(5):524–528. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gutierrez S, Comiskey CA, 4th, Luo ZP, Pupello DR, Frankle MA. Range of impingement-free abduction and adduction deficit after reverse shoulder arthroplasty: hierarchy of surgical and implant-design-related factors. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(12):2606–2615. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merolla G, Walch G, Ascione F, et al. Grammont humeral design versus onlay curved-stem reverse shoulder arthroplasty: comparison of clinical and radiographic outcomes with minimum 2-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27(4):701–710. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2017.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X, Dines JS, Warren RF, Craig EV, Dines DM. Inferior glenosphere placement reduces scapular notching in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2015;38(2):e88–e93. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20150204-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poon PC, Chou J, Young SW, Astley T. A comparison of concentric and eccentric glenospheres in reverse shoulder arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(16):e138. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.00941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torrens C, Guirro P, Miquel J, Santana F. Influence of glenosphere size on the development of scapular notching: a prospective randomized study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(11):1735–1741. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Werner BS, Chaoui J, Walch G. Glenosphere design affects range of movement and risk of friction-type scapular impingement in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2018;100(9):1182–1186. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.100B9.BJJ-2018-0264.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collotte P, Erickson J, Vieira TD, Domos P, Walch G. Midterm clinical and radiologic results of reverse shoulder arthroplasty with an eccentric glenosphere. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020;29(5):976–981. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2019.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Biase CF, Ziveri G, Delcogliano M, et al. The use of an eccentric glenosphere compared with a concentric glenosphere in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: two-year minimum follow-up results. Int Orthop. 2013;37(10):1949–1955. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-1947-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chebli C, Huber P, Watling J, Bertelsen A, Bicknell RT, Matsen F., 3rd Factors affecting fixation of the glenoid component of a reverse total shoulder prothesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(2):323–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gutierrez S, Walker M, Willis M, Pupello DR, Frankle MA. Effects of tilt and glenosphere eccentricity on baseplate/bone interface forces in a computational model, validated by a mechanical model, of reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(5):732–739. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicholson GP, Strauss EJ, Sherman SL. Scapular notching: recognition and strategies to minimize clinical impact. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(9):2521–2530. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1720-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Constant CR, Murley AH. A clinical method of functional assessment of the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;(214):160–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilbart MK, Gerber C. Comparison of the subjective shoulder value and the Constant score. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(6):717–721. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.02.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sirveaux F, Favard L, Oudet D, Huquet D, Walch G, Mole D. Grammont inverted total shoulder arthroplasty in the treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis with massive rupture of the cuff: results of a multicentre study of 80 shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(3):388–395. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.86b3.14024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gutierrez S, Levy JC, Frankle MA, et al. Evaluation of abduction range of motion and avoidance of inferior scapular impingement in a reverse shoulder model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(4):608–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levigne C, Boileau P, Favard L, et al. Scapular notching in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(6):925–935. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedman RJ, Barcel DA, Eichinger JK. Scapular notching in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019;27(6):200–209. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-17-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nyffeler RW, Werner CM, Simmen BR, Gerber C. Analysis of a retrieved delta III total shoulder prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(8):1187–1191. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.86b8.15228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paisley KC, Kraeutler MJ, Lazarus MD, Ramsey ML, Williams GR, Smith MJ. Relationship of scapular neck length to scapular notching after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty by use of plain radiographs. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(6):882–887. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ladermann A, Gueorguiev B, Charbonnier C, et al. Scapular notching on kinematic simulated range of motion after reverse shoulder arthroplasty is not the result of impingement in adduction. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94(38):e1615. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheung E, Willis M, Walker M, Clark R, Frankle MA. Complications in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(7):439–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roche CP, Stroud NJ, Martin BL, et al. The impact of scapular notching on reverse shoulder glenoid fixation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(7):963–970. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boileau P, Moineau G, Roussanne Y, O'Shea K. Bony increased-offset reversed shoulder arthroplasty: minimizing scapular impingement while maximizing glenoid fixation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(9):2558–2567. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1775-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Athwal GS, MacDermid JC, Reddy KM, Marsh JP, Faber KJ, Drosdowech D. Does bony increased-offset reverse shoulder arthroplasty decrease scapular notching. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(3):468–473. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ladermann A, Williams MD, Melis B, Hoffmeyer P, Walch G. Objective evaluation of lengthening in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(4):588–595. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nigro PT, Gutierrez S, Frankle MA. Improving glenoid-side load sharing in a virtual reverse shoulder arthroplasty model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(7):954–962. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]