Summary

Background

Successful and sustainable models for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) delivery in public health systems in Africa are needed. We aimed to evaluate the implementation of PrEP delivery integrated in public HIV care clinics in Kenya.

Methods

As part of Kenya's national PrEP roll-out, we conducted a stepped-wedge cluster-randomised pragmatic trial to catalyse scale-up of PrEP delivery integrated in 25 public HIV care clinics. We selected high-volume clinics in these regions (ie, those with a high number of people living with HIV enrolled in HIV care and treatment). Clinics (each representing a cluster) were stratified by region and randomly assigned to the order in which clinic staff would receive PrEP training and ongoing technical support using numbered opaque balls picked from a bag. There was no masking. PrEP provision was done by clinic staff without additional financial support. Data were abstracted from records of individuals initiating PrEP. The primary outcome was the number of people initiating PrEP per clinic per month comparing intervention to control periods. Other outcomes included PrEP continuation, adherence, and incident HIV infections. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03052010.

Findings

After the baseline period, which started in January, 2017, every month two to six HIV care clinics crossed over from control to intervention, until August, 2017, when all clinics were implementing the intervention. Of 4898 individuals initiating PrEP (27 during the control period and 4871 during the intervention period), 2640 (54%) were women, the median age was 31 years (IQR 25–39), and 4092 (84%) reported having a partner living with HIV. The mean monthly number of PrEP initiations per clinic was 0·1 (SD 0·5) before the intervention and 7·5 (2·7) after intervention introduction (rate ratio 23·7, 95% CI 14·2–39·5, p<0·0001). PrEP continuation was 57% at 1 month, 44% at 3 months, and 34% at 6 months, and 12% of those who missed a refill returned later for PrEP re-initiation. Tenofovir diphosphate was detected in 68 (96%) of 71 blood samples collected from a randomly selected subset of participants. Six HIV infections were observed over 2531 person-years of observation (incidence 0·24 cases per 100 person-years), three of which occurred at the first visit after PrEP initiation.

Interpretation

We observed high uptake, reasonable continuation with high adherence, frequent PrEP restarts, and low HIV incidence. Integration of PrEP services within public HIV care clinics in Africa is feasible.

Funding

National Institute of Mental Health and Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Introduction

Of the estimated 1·7 million new HIV infections in 2019, 60% occurred in the African region.1 Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) against HIV has the potential to reduce HIV incidence among populations at risk of HIV if it can be delivered with sufficient coverage.2 In 2015, WHO recommended using daily oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), in combination with emtricitabine (FTC/TDF), as a safe and effective oral PrEP for persons at risk of HIV infection globally.3 Many African countries have now developed policies that incorporate PrEP in their HIV prevention strategies.4

There are extensive data from high-income countries describing diverse settings in which PrEP services are offered, including in clinics treating sexually transmitted infections, community-based organisations, commercial pharmacies, and through primary care and specialty providers.5, 6 In contrast, data describing PrEP scale-up models in low-income and middle-income countries are scarce. In many African countries, public HIV care and treatment programmes have been very successful at scaling up antiretroviral therapy (ART) over the past 15 years and are an attractive choice for integration of PrEP delivery.7, 8 HIV care clinics in Africa routinely provide HIV prevention services including HIV testing services and condom distribution to uninfected partners of persons living with HIV, thus providing a ready PrEP-eligible population.7, 9 In addition, health-care providers in these clinics are conversant with prescribing and counselling on antiretroviral medication use, and the clinics have an established commodity management system for ART and HIV test kits.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Daily pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine is a highly effective HIV prevention intervention. Delivery of PrEP at scale to people at substantial risk of HIV infection is necessary in order to attain maximal public health impact. Successful models of PrEP delivery have been described in high-income countries; however, there are few data that describe sustainable approaches for delivery of PrEP for HIV prevention for low-income and middle-income settings.

Added value of this study

We conducted a real-world PrEP implementation programme in which PrEP services were integrated into public HIV care clinics in Kenya. We demonstrate that, by improving the capacity of health providers in those care clinics to offer PrEP services through training and technical support, PrEP uptake increased more than 20-fold and was sustained. With existing personnel and infrastructure, the high-volume HIV care clinics efficiently reached partners of persons living with HIV and other populations at HIV risk. PrEP users had reasonable continuation rates and objective evidence of high adherence. Restarting PrEP was common.

Implications of all the available evidence

We demonstrate that provision of PrEP services integrated in public HIV care clinics in Africa is feasible. Our findings inform Kenya's national scale-up of PrEP and other countries in the African region that are considering implementation of national PrEP programmes.

In 2017, Kenya launched a national commitment to PrEP as part of the HIV combination prevention strategy, focusing on holistic integration of PrEP service delivery within the public health system.10 Data from clinical trials and demonstration projects of PrEP conducted in Kenya proved critical for regulatory approval and normative guidance formation related to PrEP, and thus the country was well positioned to advance PrEP services early in Africa.11, 12 To provide real-world evidence of PrEP implementation in public HIV clinics in Kenya, and within Kenya's national PrEP programme, we did an implementation trial of PrEP service delivery in 25 HIV care clinics.

Methods

Study design and setting

The Partners Scale-Up Project is a prospective pragmatic evaluation of the implementation of PrEP delivery integrated in 25 public HIV care clinics.13 For this evaluation, we applied a stepped-wedge cluster-randomised trial design, with each clinic as a cluster, taking into account a staggered approach because the intervention could not be implemented simultaneously in all clinics. The intervention consisted of PrEP training for health-care workers and provision of ongoing PrEP technical assistance to HIV clinics. The first month of the study constituted a baseline period, during which no intervention activities were implemented at any health facility. Subsequently at monthly intervals, two to six HIV care clinics crossed over from control to intervention.

Kenya has a generalised HIV epidemic with 4·9% of the adult population living with HIV and an estimated 36 000 new infections annually.14 The majority of people living with HIV in the country receive care and treatment services from public HIV care clinics. At these clinics, clients are encouraged to bring their partners for HIV testing, therefore providing a population that would benefit from PrEP should they test HIV negative.15 Staffing at the clinics typically includes clinical officers, nurses, pharmaceutical technologists, laboratory technicians, data clerks, HIV testing service providers, and lay health workers. In consultation with the Kenyan National AIDS and STI Control Program (NASCOP) and county-level health officials, we identified 24 high-volume public health HIV care clinics in western (former Nyanza province) and central (including former Central and Nairobi provinces) regions, areas with medium-to-high HIV incidence.16 We selected high-volume clinics in these regions (ie, those with a high number of people living with HIV enrolled for HIV care and treatment). All 24 identified clinics were invited and agreed to participate in the project, and one of the clinics later added on a satellite clinic.

This programme implementation evaluation protocol was approved by the scientific and ethics review unit of the Kenya Medical Research Institute, Nairobi (SERU/CCR/0048/3328, SERU/CMR/0040/3338) and the University of Washington Human Subjects Division, Seattle, USA (STUDY00002183) enabling analysis of de-identified and delinked programmatic data. Thus, individual consent was not required. People who participated in random blood draws for detection of tenofovir diphosphate provided written informed consent. An independent data monitoring committee reviewed data from the project, including project execution, PrEP user risks, and factors that might impact implementation. The committee held open session meetings approximately every 6 months (appendix p 17).

Randomisation and masking

Clinics (each representing a cluster in the design) were stratified by region and then randomly assigned to the order in which they would start receiving the intervention. The randomisation process was conducted at two stakeholder events (one in the western region and another in central region) attended by county health officials, facility management, and study leadership. A representative from the health facility picked out an opaque ball from a bag. The balls, prepared by the study coordinator, contained numbers 1 to 12 representing the position of the clinic in the order of project implementation. There was no masking for this study.

Procedures

Health-care providers, likely to come into contact with persons at risk of HIV and hence eligible for PrEP or likely to be involved in provision of PrEP services at the facility were selected to be trained. The selection was done by the facility management. They received 2-day hotel-based interactive PrEP training using a curriculum developed by the Kenya Ministry of Health in collaboration with implementing partners, including the study team.17 534 (75%) of the 716 trained providers were nurses, clinical officers, or HIV counsellors.18 The training topics included introduction to PrEP, risk assessment and indications for PrEP, procedures at initiation and follow-up visits, and documentation of visits. The training had didactic sessions, discussions of case studies, role plays, and practical exercises. Pre-training and post-training assessments were done to assess PrEP knowledge.

Health-care providers began providing PrEP services including demand creation, risk assessment, prescribing, counselling, and retention activities within a month after training. Services were provided by Ministry of Health staff including clinical officers, nurses, and HIV counsellors already stationed at these clinics. No additional staffing or financial support was provided to the clinics; thus, services were provided without altering the existing infrastructure. All PrEP medication and HIV test kits were provided by the Kenya Ministry of Health.

Project staff who had previously developed expertise in PrEP research and clinical delivery served as technical advisers, mentoring health-care providers in participating clinics in PrEP delivery following the standardised PrEP training. Technical advisers were nurses and clinical officers employed by the study, and they also led the training of health-care providers. Each technical adviser provided support for up to four clinics. Technical assistance activities involved supporting providers to do demand creation activities by modelling health talks at facility waiting bays, and real-time consultation (eg, when providers needed clarity on determination of eligibility and how to complete various Ministry of Health clinical, pharmacy, or monitoring and evaluation tools). They also identified and addressed training gaps, and they facilitated continuous medical education and on-job-training sessions. They visited clinics at least twice a month in the first year and monthly or less frequently thereafter as facilities became comfortable with PrEP delivery. Observations made during technical assistance visits were detailed in structured reports. Technical advisers met weekly as a group to discuss observations made across facilities and best practices were shared across clinics.

Kenya normative guidelines recommend PrEP for HIV-uninfected individuals who report multiple sex partners, a history of a recent sexually transmitted infection, no or inconsistent condom use, engagement in transactional sex, recurrent use of post-exposure prophylaxis, recreational drug use, or having partners living with HIV who are not virally suppressed. In 2017, Kenya committed that PrEP would be available at public health facilities nationwide.

PrEP services were provided according to Kenya Ministry of Health guidelines.19 Those guidelines recommend behavioural risk assessments and clinical review before issuing PrEP prescriptions. Screening for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among people seeking PrEP services was syndromic according to Kenyan Ministry of Health standard of care guidelines. Although serum creatinine testing at baseline is recommended, the guidelines advise that lack of testing should not delay PrEP initiation. Creatinine testing at the facilities was either available at a fee or, if not available, clients were referred to other facilities for testing, also at a fee. PrEP users were advised to attend clinical visits one month after initiation and quarterly thereafter while PrEP need was ongoing; at those visits, medication side-effects and adherence via self-report were determined. PrEP was to be discontinued for individuals testing HIV seropositive.

At most clinics, providers elected to contact participants with missed appointments via telephone (similar to standard practice for people living with HIV receiving ART) and issue new appointments if there was interest in continuing PrEP services. Health-care providers documented when PrEP users were not expected to return for refill visits—eg, when PrEP users reported they no longer wanted PrEP. Individuals who failed to attend a visit and could not be contacted were considered discontinued and not expected to attend the next scheduled visit.

To measure adherence, whole-blood samples were obtained from individuals returning for PrEP refill visits at randomly selected clinics on a random subset of days in a month. The blood was transported to centralised project sites where dried blood spots were prepared. Intracellular tenofovir diphosphate concentrations were determined from the dried blood spots using validated liquid chromatography-tandem spectrometry.20, 21 Additionally, for each person initiating PrEP we determined the number of PrEP pills they received during the first 6 months after PrEP start.

Kenya Ministry of Health standard clinic encounter form records of individuals receiving PrEP services were abstracted by trained project staff onto a central database using the SurveyCTO platform. Records included demographic information, behaviour risk assessment evaluation, medical assessment and syndromic STI evaluation, laboratory test requests and results, details of PrEP dispensing, and adherence assessment (appendix p S20). We abstracted data for all people aged 18 years and older initiating PrEP in the facilities over the duration of the study.

Outcomes

The primary outcome for this evaluation was the number of people initiating PrEP per clinic per month compared between the intervention and the control periods. Other pre-specified secondary outcomes were the number of people continuing to use PrEP, adherence to PrEP, incident HIV infections, and fidelity to core components of PrEP delivery.

Statistical analysis

For the primary outcome, the number of people initiating PrEP per clinic per month, PrEP initiation was defined as documentation of having received a PrEP prescription in facility records. Visit dates and windows (the period between 15 days before the expected visit date to 15 days before the next expected visit date) were determined for all persons initiating PrEP based on the initiation date. For the secondary outcomes, PrEP continuation was defined as the proportion of people initiating PrEP who had a documented PrEP refill within the visit window. To determine the extent of programme implementation fidelity, we reported the proportion of visits in which core components of PrEP delivery were completed. These included HIV risk assessment, HIV testing and acute HIV infection assessment before PrEP initiation, baseline serum creatinine testing and STI screening, and PrEP prescription and dispensing. The objective measure of adherence was intracellular tenofovir diphosphate concentrations in dried blood spots obtained from individuals returning for PrEP refill visits at randomly selected clinics on a random subset of days in a month.

We estimated power for the primary endpoint of PrEP initiations. Using 24 clinics with a baseline period, two-to-four clinics implementing at each step, and 50 at-risk HIV-uninfected persons initiating PrEP per clinic every 6 months (4800 individuals in total) we would have more than 90% power to detect a minimum 10% absolute difference in the number of at-risk HIV-uninfected individuals initiating PrEP after implementing the intervention with a two-sided α of 0·05. A coefficient of variation of 0·1 was selected for this study design. We observed an adjusted intracluster correlation coefficient of 0·074.

Descriptive analyses of demographic, HIV risk, and fertility characteristics of people initiating PrEP were performed. For those reporting sex partners living with HIV, HIV risk was summarised on the basis of an empiric risk score developed to quantify HIV risk among HIV serodiscordant couples.22 Characteristics assessed to calculate the score included age of the HIV uninfected partner, number of children within the partnership, circumcision status of HIV uninfected men, whether the couple was cohabiting, and having unprotected sex in the month preceding the start of PrEP. In previous studies of HIV serodiscordant couples a score of 3 or higher was associated with an HIV incidence greater than 3% per year.22 We conducted a cluster-level analysis to determine change in number of people initiating PrEP per clinic per month between intervention and control periods using a negative binomial mixed effects model with log link. The model also included step, clinic volume, and region as fixed effects, and a random effect for each clinic. To determine whether number of monthly PrEP initiations per clinic changed over time after intervention implementation, we conducted an analysis restricted to the intervention period using a negative binomial mixed effects model with log link. The model included duration since start of PrEP implementation in years as the primary exposure, region, clinic volume, and calendar time as fixed effects, and a random effect for each clinic.

We present proportions of all people initiating PrEP and of those expected to return for refill visits who had PrEP refills at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after PrEP initiation. We determined the proportion of randomly obtained dried blood spots that have tenofovir diphosphate detected and the proportion of all initiation visits in which core components of PrEP service delivery were completed.

To calculate HIV incidence, we divided the number of new HIV infections by the accrued person-time of follow-up. Participants were censored either in December, 2019 (for those continuing PrEP use at the end of the project), at last clinic visit, or at seroconversion. To estimate the potential impact of PrEP availability on incident HIV, we compared the number of observed new HIV infections with an expected HIV incidence estimated using a simulated counterfactual model with data from the placebo group of the Partners PrEP Study,11 a clinical trial done in HIV serodiscordant couples in Kenya and Uganda. Comparisons were limited to individuals reporting a sex partner known to be living with HIV and to follow-up within the first year of starting PrEP. The comparison limited to serodiscordant partnerships potentially reduces temporal trends in HIV transmission risk in communities, as the principal risk of HIV is from within the partnership.12 We constructed 10 000 bootstrap samples of 4092 couples each with a distribution of sex and HIV risk scores to match the population in the Partners Scale-Up Project.22 The number of HIV seroconversions was predicted for each bootstrap sample and the counterfactual population incidence determined as the mean number of HIV seroconversions across the 10 000 samples. The 95% CI was the number of seroconversions from the 250th and 9750th datasets after sorting by number of seroconversions. HIV incidence for the counterfactual population was computed by dividing the mean number of seroconversions by the mean follow-up time from 10 000 bootstrap samples. The incidence rate ratio was computed by comparing observed HIV incidence in this study with the computed counterfactual estimate and the 95% CI was calculated using a Poisson distribution. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted, with follow-up limited to 6 months after starting PrEP.

Analyses were done using the R software 3.5.2 and Stata version 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Role of the funding source

The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the manuscript.

Results

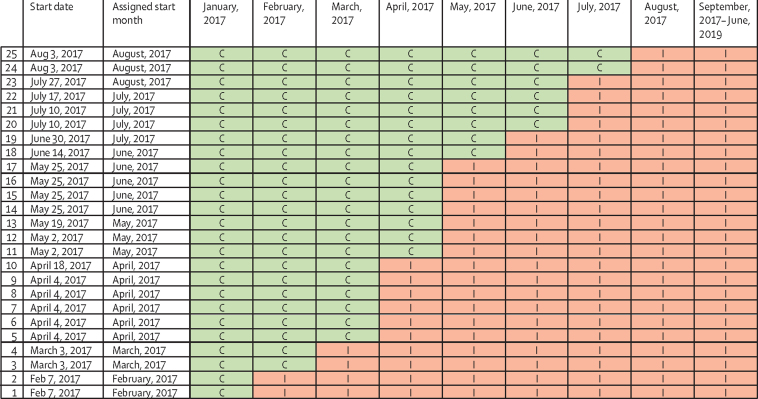

The baseline period started in January, 2017, during which no intervention activities were implemented at any health facility (figure 1). Subsequently at monthly intervals, beginning Feb 7, 2017, two to six HIV care clinics crossed over from control to intervention. By August, 2017, all clinics were implementing the intervention and follow-up continued until Dec 6, 2019.

Figure 1.

Order of implementation across clinics

C=control period. I=implementation period.

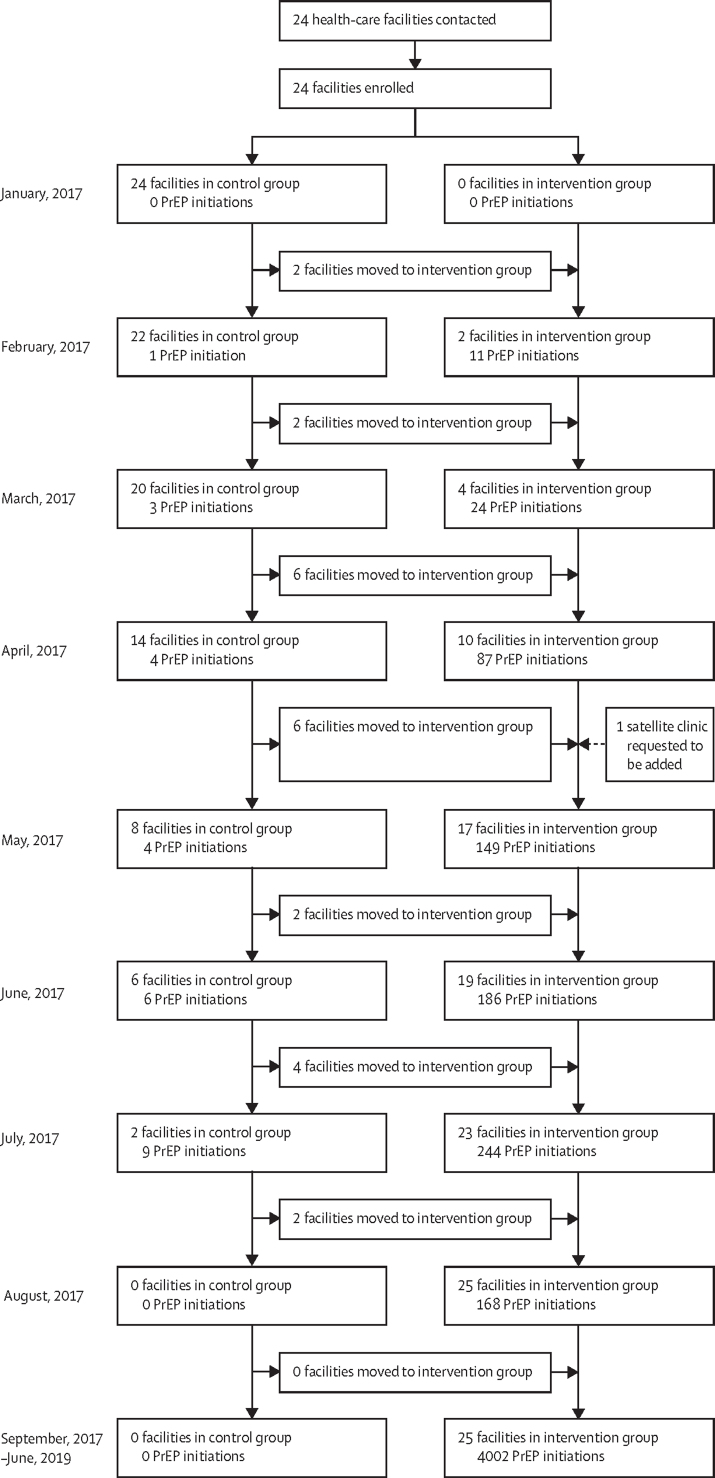

4898 people initiated PrEP in the 25 public HIV clinics between Jan 10, 2017 and June 7, 2019: 27 during the control period and 4871 in the period after intervention (figure 2). The mean monthly number of PrEP initiations per clinic was 0·1 initiations (SD 0·5) before intervention implementation and 7·5 initiations (2·7) after implementation (rate ratio [RR] 23·7, 95% CI 14·2–39·5, p <0·0001). PrEP initiations were relatively stable: each additional year after intervention implementation was associated with a 5% relative reduction (RR 0·95 (95% CI 0·80–1·13, p=0·5) in the number of people initiating PrEP per clinic per month—a change that was not significant.

Figure 2.

Trial profile

PrEP=pre-exposure prophylaxis.

The median age of those initiating PrEP was 31 years (IQR 25–39), and 2640 (54%) of people starting PrEP were women (table). The majority (4092 [84%]) reported having a sex partner living with HIV and they had known their HIV serodiscordant status for a median 1 year (IQR 0·2–4·5) before starting PrEP. 2845 (70%) of 4092 of those in serodiscordant partnerships had a risk score of 3 and above, associated with an anticipated HIV incidence greater than 3%. Besides having a partner living with HIV, individuals initiating PrEP reported other HIV risk behaviour that made them eligible for PrEP initiation, including inconsistent or no condom use (2817 [58%] participants), not knowing the HIV status of their partners (789 [16%] participants), and having sex with multiple partners (565 [12%] participants).

Table.

Baseline demographic characteristics and HIV risk behaviour of individuals initiating PrEP and predictors of having at least one refill visit in the first 3 months

| All participants initiating PrEP (n=4898) | Participants with at least one visit within 3 months of PrEP start (n=3028) | OR (95%CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Men | 2257 (46%) | 1355/2257 (60%) | 1 (ref) | |

| Women | 2640 (54%) | 1672/2640 (63%) | 1·15 (1·03–1·29) | |

| Age, years | ||||

| 18–24 | 969 (20%) | 526/969 (54%) | 1 (ref) | |

| 25–34 | 2118 (43%) | 1304/2118 (62%) | 1·35 (1·16–1·57) | |

| ≥35 | 1811 (37%) | 1198/1811 (66%) | 1·65 (1·40–1·93) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 347 (7%) | 137/347 (39%) | 1 (ref) | |

| Married or cohabitating | 4466 (91%) | 2843/4466 (64%) | 2·67 (2·15–3·35) | |

| Widowed or separated | 85 (2%) | 48/85 (56%) | 1·99 (1·23–3·21) | |

| Reported HIV risk behaviour | ||||

| Has HIV positive partner | 4092 (84%) | 2676/4092 (65%) | 2·44 (2·09–2·84) | |

| Inconsistent or no condom use | 2817 (58%) | 1741/2817 (62%) | 1·00 (0·89–1·12) | |

| Unknown status of sex partner | 789 (16%) | 379/789 (48%) | 0·51 (0·44–0·59) | |

| Multiple partners | 565 (12%) | 267/565 (47%) | 0·51 (0·43–0·61) | |

| Recurrent sex under the influence of alcohol | 111 (2%) | 54/111 (49%) | 0·58 (0·40–0·84) | |

| Engaging in transactional sex | 67 (1%) | 26/67 (39%) | 0·38 (0·24–0·63) | |

| Recurrent PEP use | 55 (1%) | 31/55 (56%) | 0·80 (0·47–1·36) | |

| Recent sexually transmitted infection | 44 (1%) | 27/44 (61%) | 0·98 (0·53–1·80) | |

| Ongoing intimate-partner or gender-based violence | 35 (1%) | 17/35 (49%) | 0·58 (0·30–1·12) | |

| Injection drug use | 5 (<1%) | 5/5 (100%) | .. | |

| Not circumcised (men only)* | 385/1965 (20%) | 237/385 (62%) | 0·99 (0·82–1·20) | |

| Characteristics of HIV serodiscordant couples (n=4092) | ||||

| Number of children with partner* | ||||

| 0 | 888/2502 (35%) | 618/888 (70%) | 1 (ref) | |

| 1–2 | 957/2502 (38%) | 653/957 (68%) | 0·94 (0·77–1·14) | |

| 3 or more | 657/2502 (26%) | 469/657 (71%) | 1·09 (0·87–1·36) | |

| Time known to be discordant | ||||

| <1 year | 1093/2468 (44%) | 743/1093 (68%) | 1 (ref) | |

| 1–3 years | 613/2468 (25%) | 432/613 (70%) | 1·12 (0·91–1·39) | |

| >3 years | 760/2468 (31%) | 538/760 (71%) | 1·14 (0·93–1·40) | |

| HIV risk score† | ||||

| 0–2 | 1247/4092 (31%) | 785/1247 (63%) | 1 (ref) | |

| ≥3 | 2845/4092 (70%) | 1891/2845 (67%) | 1·17 (1·02–1·34) | |

| Pregnancy and fertility (n=2640 women) | ||||

| Pregnant* | 167/1486 (11%) | 114/167 (68%) | 1·26 (0·90–1·78) | |

| Breastfeeding* | 262/1687 (16%) | 163/262 (62%) | 0·89 (0·68–1·17) | |

| Using contraception* | 968/1820 (53%) | 633/968 (65%) | 0·90 (0·74–1·09) | |

| Fertility desires* | ||||

| No fertility desires | 648/1510 (43%) | 400/648 (62%) | 1 (ref) | |

| Immediate | 318/1510 (21%) | 241/318 (76%) | 1·94 (1·44–2·62) | |

| Future | 479/1510 (32%) | 309/479 (65%) | 1·13 (0·88–1·44) | |

| Don't know | 65/1510 (4%) | 40/65 (62%) | 0·99 (0·59–1·68) | |

Data are n (%) or n/N (%), unless otherwise specified. PEP=post-exposure prophylaxis. PrEP=pre-exposure prophylaxis.

There are missing data for various variables as follows: male circumcision 292 (13%), number of children with partner 1590 (39%), time known to be HIV discordant 1624 (40%), pregnancy 1154 (44%), breastfeeding 771 (31%), contraception 820 (31%), and fertility desires 1130 (43%).

HIV risk score was calculated from the following characteristics: age of the HIV uninfected partner, number of children within the partnership, circumcision status of HIV uninfected men, whether the couple was cohabiting, and having unprotected sex in the month before starting PrEP.

Among the women with available data, 167 (11%) of 1486 were pregnant and 262 (16%) of 1687 were breastfeeding a child at the time of PrEP initiation. Among women with available data, 53% (968 of 1820) reported using contraception and 21% (318 of 1510) had immediate desire for fertility.

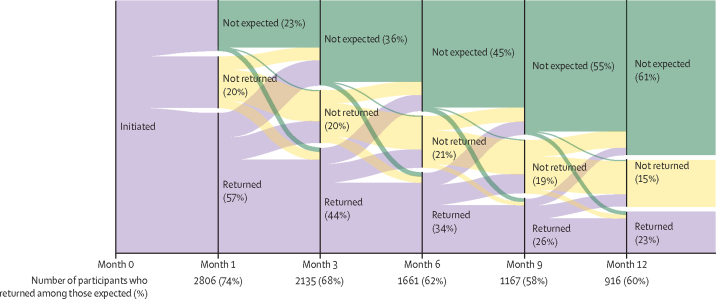

Of the 4898 people who initiated PrEP, 2806 (57%), 2135 (44%), 1661 (34%), and 916 (23%) returned for refill visits at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months after PrEP initiation, respectively. However, the documentation stating that individuals were no longer expected to return for PrEP was often missing. Overall, there were 4025 reasons documented for which PrEP users were not expected to attend PrEP refill visits. Unsuccessful attempts to contact PrEP users made up the majority of documented reasons (3388 [84%]). Among those successfully contacted, reasons why PrEP users were not expected to attend PrEP refill visits included reduced HIV risk (358 [56%] of 639) due to HIV positive partner viral suppression, decision to use condoms consistently, realisation of conception (and subsequent consistent condom use), relocation away from clinic area (161 [25%]), experience of side-effects (33 [5%]), and other reasons including pill burden and being busy (88 [14%]).

Excluding individuals known to have discontinued PrEP (number varied with each visit), the proportion expected to return for visits was 77% at month 1 (3789 of 4898 participants), 64% at month 3 (3136 of 4898 participants), 54% at month 6 (2671 of 4895 participants), and 39% at month 12 (1529 of 3967 participants). Of those expected, 74% (2806 of 3789), 68% (2135 of 3136), 62% (1661 of 2671), and 60% (916 of 1529) attended their refill visits at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after PrEP initiation. At all quarterly visits, 12% of participants who had failed to attend the previous refill visit returned for PrEP medication (ie, effectively restarting PrEP; figure 3). The median time to PrEP restart was 90 days (IQR 62–150).

Figure 3.

PrEP continuation

The figure shows the proportion of PrEP users returning (purple), not returning (yellow), and not expected (green) for PrEP refill visits, by month. It also shows individuals with missed previous visits returning for PrEP refills. PrEP=pre-exposure prophylaxis.

A total of 3028 individuals (62% of those starting PrEP) had at least one refill visit within the first 3 months of PrEP initiation. Women (odds ratio 1·15, 95% CI 1·03–1·29), individuals older than 24 years (1·48, 1·28–1·70), those married or cohabitating (2·67, 2·15–3·35), those who were widowed or separated (1·99, 1·23–3·21), those reporting a partner living with HIV (2·44, 2·09–2·84), and women with immediate fertility desires (1·94, 1·44–2·62) had increased odds of having at least one refill visit in the 3 months after PrEP initiation. In addition, among individuals having a sex partner living with HIV, those with an HIV risk score of 3 or greater had greater odds of having a visit within 3 months of PrEP initiation (1·17, 95% CI 1·02–1·34; table).

Over the course of the study, participants self-reported good adherence to PrEP at 70% (95% CI 69–71) of follow-up visits. 71 dried blood spots were collected and tested. The median duration of PrEP use at sampling time was 1 month (range 1–4). Tenofovir diphosphate was detectable in 68 (96%) samples and the median tenofovir diphosphate concentration was 515 fmol per punch (IQR 348–693), similar to 560 fmol per punch, which is the estimate for at least four doses per week on average at approximately 1 month, taken from a directly observed dosing study in the USA.21 Mean detectable tenofovir diphosphate concentrations were similar (p>0·05) by sex, age, and desire to conceive (data not shown). The median medication possession for oral PrEP in the first 6 months among all individuals initiating PrEP was 50% (95% CI 17–98).

A total of 2531 person-years of follow-up were accrued with a mean follow-up of 6·3 months (SD 8·1). Six individuals (five women and one man) initiating PrEP tested HIV positive during the project period, translating to an HIV incidence of 0·24 cases per 100 person-years. All seroconversions occurred within the first year and three of these individuals tested HIV positive at the first visit after PrEP initiation. For people reporting sex partners living with HIV, HIV incidence during the first year of PrEP use was 0·42 cases per 100 person-years (six events in 1423 person-years). This incidence represents a 90% reduction (95% CI 76–95) compared with a predicted incidence of 4·05 cases per 100 person-years (95% CI 3·4–4·7), which would be expected for HIV serodiscordant partners with similar sex and risk characteristics in the absence of PrEP and ART. Sensitivity analyses comparing predicted with observed HIV incidence at 6 months of PrEP use did not yield substantially different results (predicted incidence 3·79 cases per 100 person-years [95% CI 2·7–5·0] vs observed incidence 0·65 cases per 100 person-years [0·24–1·43]).

At PrEP initiation, HIV risk assessment was documented for all individuals. HIV testing was documented to have been done at 99·8% of initiation visits, acute HIV assessment at 99·5% of initiation visits, and PrEP dispensing at 99·5% of initiation visits. Assessment of sexually transmitted infections was done at 87% of visits. Over the entire project period, 138 (3%) of all 4898 participants had a creatinine test result recorded: 61 at baseline and 77 during PrEP follow-up.

Discussion

In this large-scale evaluation of PrEP delivery in Kenya, we observed sustained high monthly uptake of PrEP, demonstrating that public HIV care clinics are a feasible delivery setting for integrating PrEP services. The clinics, which attend to hundreds of people living with HIV every month, comfortably added an average of seven PrEP initiations per month per clinic, with high fidelity and utilising their existing infrastructure and workforce. It is interesting to note that although the majority of individuals initiating PrEP in these clinics reported having a sex partner known to have HIV, almost one in five did not, suggesting that other at-risk populations might find public HIV care clinics an acceptable venue for receiving PrEP services. There was high adherence among those who continued to take PrEP, with almost all tested samples having evidence of use of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate with emtricitabine.

We observed that individuals discontinued PrEP use over time, and for many individuals PrEP use might have been aligned to HIV risk, a concept described as prevention-effective adherence.23 People with HIV risk scores associated with increased risk of HIV infection at baseline were more likely to continue using PrEP for greater than 3 months. Additionally, among those who provided reasons for discontinuation, over 50% were related to perception of reduced HIV risk, including viral suppression of their partners living with HIV who had initiated ART or decisions to use condoms consistently. Use of PrEP is not expected to be lifelong and individuals are encouraged to discontinue when they are no longer at risk.24 For HIV serodiscordant couples, use of PrEP in a time-limited fashion before and for the first months of ART (ie, as a bridge to viral suppression) is recommended by evidence-supportive normative guidance.12

Notably, about 12% of people who had failed to attend a refill visit showed up for a refill at the next visit, suggesting that individuals continued to think about and assess their HIV risk and resumed PrEP when they needed to. Similar reports of PrEP restarts were reported in other PrEP settings.25 Since most people will not inform health providers of their intent to discontinue PrEP, a receptive attitude by providers in HIV care clinics to individuals who have previously discontinued PrEP use or have had missed refill visits will probably encourage PrEP restarts, as has been observed in HIV treatment programmes.26, 27 In addition, clinics should strive to address barriers that might keep clients from returning for services such as long waiting times that would be a deterrent for those with busy schedules.28

There was high fidelity in implementation of the PrEP programme in public health facilities; specifically, we observed almost universal HIV testing, acute HIV assessment, and behavioural risk evaluation before PrEP initiation. Kenya national PrEP guidelines recommend creatinine testing at baseline but permit PrEP initiation and continuation if the test is not available for individuals without risk factors for renal disease.19 Most people initiating PrEP in the facilities did not have creatinine testing at baseline; however, they were relatively young and therefore less likely to have pre-existing conditions that predispose to renal compromise. Our findings demonstrate the feasibility of implementing a PrEP programme in public health facilities where laboratory testing might not be readily available and accessible.

As PrEP is a biomedical intervention, increasing the capacity of health-care providers working in public HIV clinics, including nurses, clinical officers, and HIV counsellors to offer PrEP services is critical. Training health providers and providing technical support during implementation was associated with increased PrEP service delivery in participating clinics. To achieve rapid scale-up of PrEP services in the country it is crucial that efficient, cost-effective training modalities and innovative means of providing technical assistance are employed. These will ensure that health providers in public health facilities acquire knowledge about PrEP and feel confident in their ability to offer services.18, 29

There are strengths to this study. First, we conducted the study in 25 high-volume public HIV care clinics distributed in various geographical areas within central and western Kenya, increasing the generalisability of our findings. Second, use of the stepped-wedge study design enabled us to rigorously evaluate the impact of our intervention within the national programmatic scale-up of PrEP. There are also several limitations to our study. First, for many of the people who did not continue to use PrEP, their clinic documentation did not demonstrate a reason for discontinuation and their HIV status after discontinuation could not be determined. Second, our analysis used programmatic data abstracted from client records, which often has problems of completeness.30 Third, this study was conducted in high-volume HIV care clinics and might not be generalisable to smaller HIV clinics or to clinics without ART programmes. Finally, we used a counterfactual simulation model to compare HIV incidence in this project with the incidence anticipated in the absence of PrEP and ART and, like all non-contemporaneous comparisons, this counterfactual could be subject to bias. Of note, although secular changes in HIV transmission risk might have occurred, the main HIV transmission risk stems from within the HIV serodiscordant partnership, mitigating some risk of bias in this approach.

In this study of PrEP delivery integrated in public HIV care clinics in Kenya, PrEP uptake was high, continuation was reasonable, and those who continued to attend clinics had high adherence and low rates of HIV acquisition. Integration of PrEP in public health facilities is feasible and can be done with high fidelity when health providers are trained and receive technical support related to PrEP service delivery. Evidence from this work will inform other countries in the region that are considering implementation of national PrEP programmes.

Data sharing

The study protocol, statistical plan, and data from the Partners Scale-Up Project are available by contacting the International Clinical Research Center at the University of Washington (icrc@uw.edu).

Declaration of interests

JMB reports personal fees from Gilead Sciences, outside the submitted work. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health of the US National Institutes of Health (grant R01MH095507) and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (grant OPP10556051). We thank the members of the independent data monitoring committee for their expertise and guidance: Churchill Alumasa, Jared Mecha, Vernon Mochache, Irene Mukui, Carol Ngunu, and Jeremy Penner.

Contributors

JMB conceptualised and designed the study and obtained funding. JO and EW were involved in data collection. EMI, KKM, and SP had access to and verified the underlying data. EMI, KKM, DD, SP, and JMB analysed and interpreted the data. EMI wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors were involved in further development, review, and approval of the manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS . Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; Geneva, Switzerland: 2020. UNAIDS data 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fonner VA, Dalglish SL, Kennedy CE, et al. Effectiveness and safety of oral HIV preexposure prophylaxis for all populations. AIDS. 2016;30:1973–1983. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2015. Guidelines on when to start antiretroviral therapy and on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irungu EM, Baeten JM. PrEP rollout in Africa: status and opportunity. Nat Med. 2020;26:655–664. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0872-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayer KH, Chan PA, R Patel R, Flash CA, Krakower DS. Evolving models and ongoing challenges for HIV preexposure prophylaxis implementation in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77:119–127. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sullivan PS, Siegler AJ. Getting pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to the people: opportunities, challenges and emerging models of PrEP implementation. Sex Health. 2018;15:522–527. doi: 10.1071/SH18103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Malley G, Barnabee G, Mugwanya K. Scaling-up PrEP delivery in sub-saharan Africa: what can we learn from the scale-up of ART? Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2019;16:141–150. doi: 10.1007/s11904-019-00437-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Venter WD. What does preexposure prophylaxis mean for treatment; what does treatment mean for preexposure prophylaxis? Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2016;11:35–40. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mugo NR, Ngure K, Kiragu M, Irungu E, Kilonzo N. The preexposure prophylaxis revolution; from clinical trials to programmatic implementation. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2016;11:80–86. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP) NASCOP; Nairobi, Kenya: 2017. Framework for the implementation of pre-exposure prophylaxis of HIV in Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baeten JM, Heffron R, Kidoguchi L, et al. Integrated Delivery of Antiretroviral Treatment and Pre-exposure Prophylaxis to HIV-1-Serodiscordant Couples: A Prospective Implementation Study in Kenya and Uganda. PLoS Med. 2016;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mugwanya KK, Irungu E, Bukusi E, et al. Scale up of PrEP integrated in public health HIV care clinics: a protocol for a stepped-wedge cluster-randomized rollout in Kenya. Implement Sci. 2018;13:118. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0809-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP) NASCOP; Nairobi: 2020. Preliminary KENPHIA 2018 Report. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Odoyo JB, Morton JF, Ngure K, et al. Integrating PrEP into HIV care clinics could improve partner testing services and reinforce mutual support among couples: provider views from a PrEP implementation project in Kenya. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22(suppl 3) doi: 10.1002/jia2.25303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National AIDS Control Council . Ministry of Health; Kenya: 2018. Kenya HIV Estimates Report 2018. Nairobi. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masyuko S, Mukui I, Njathi O, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis rollout in a national public sector program: the Kenyan case study. Sex Health. 2018;15:578–586. doi: 10.1071/SH18090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Irungu EM, Ngure K, Mugwanya K, et al. Training health care providers to provide PrEP for HIV serodiscordant couples attending public health facilities in Kenya. Glob Public Health. 2019;14:1524–1534. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2019.1588908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ministry of Health. National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP) NASCOP; Nairobi, Kenya: 2018. Guidelines on Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infections in Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng JH, Rower C, McAllister K, et al. Application of an intracellular assay for determination of tenofovir-diphosphate and emtricitabine-triphosphate from erythrocytes using dried blood spots. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2016;122:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2016.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson PL, Liu AY, Castillo-Mancilla JR, et al. Intracellular tenofovir-diphosphate and emtricitabine-triphosphate in dried blood spots following directly observed therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;62:e01710–e01717. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01710-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kahle EM, Hughes JP, Lingappa JR, et al. An empiric risk scoring tool for identifying high-risk heterosexual HIV-1-serodiscordant couples for targeted HIV-1 prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62:339–347. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827e622d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haberer JE, Bangsberg DR, Baeten JM, et al. Defining success with HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: a prevention-effective adherence paradigm. AIDS. 2015;29:1277–1285. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2017. Implementation tool for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) of HIV infection. Module 1: Clinical. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koss CA, Charlebois ED, Ayieko J, et al. Uptake, engagement, and adherence to pre-exposure prophylaxis offered after population HIV testing in rural Kenya and Uganda: 72-week interim analysis of observational data from the SEARCH study. Lancet HIV. 2020;7:e249–e261. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30433-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krakower D, Mayer KH. Engaging healthcare providers to implement HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012;7:593–599. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3283590446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zanolini A, Sikombe K, Sikazwe I, et al. Understanding preferences for HIV care and treatment in Zambia: evidence from a discrete choice experiment among patients who have been lost to follow-up. PLoS Med. 2018;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ongolly FK, Dolla A, Ngure K, et al. “I just decided to stop”: understanding PrEP discontinuation among individuals initiating PrEP in HIV care centers in Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;87:e150–e158. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krakower D, Ware N, Mitty JA, Maloney K, Mayer KH. HIV providers' perceived barriers and facilitators to implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis in care settings: a qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:1712–1721. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0839-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagenaar BH, Sherr K, Fernandes Q, Wagenaar AC. Using routine health information systems for well-designed health evaluations in low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31:129–135. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czv029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The study protocol, statistical plan, and data from the Partners Scale-Up Project are available by contacting the International Clinical Research Center at the University of Washington (icrc@uw.edu).