Abstract

This cohort study examines mortality data from Texas, a racially and ethnically diverse state, to better understand excess mortality among adults aged 25 to 44 years during early months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the United States, adults aged 25 to 44 years had the largest relative increase in all-cause mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, with disproportionate increases among Black, Hispanic, and Latino adults.1,2 In the first 6 months of the pandemic, the number of COVID-19–attributed deaths among people aged 25 to 44 years in regions with major outbreaks was similar to or exceeded the number to deaths from drug overdoses, which has been the usual leading cause of death in this age group in prior years.3 To better understand excess mortality among adults aged 25 to 44 years during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, we examined mortality data from Texas, a racially and ethnically diverse state.

Methods

Using records from the Texas Department of State Health Services, we obtained monthly mortality data (stratified by race and ethnicity [Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, and non-Hispanic White]) among adults aged 25 to 44 years residing in Texas for the 6 leading causes of death (2015-2020) and COVID-19 (March-December 2020).4 The 6 leading causes of death were accidents (excluding unintentional overdoses), malignant neoplasms, diseases of the heart, intentional self-harm, assault (homicide), and unintentional overdoses (see eAppendix in the Supplement for diagnosis codes). To estimate 2020 population data, we used Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data for 2015 through 2019 and autoregressive integrated moving averaging as previously reported.3 We calculated incident mortality rates and corresponding 95% CIs for cause-specific mortality. For each racial and ethnic group, the cause of death with the greatest incident rate was considered the leading cause, as well as any other cause whose 95% CI overlapped with the 95% CI of the leading cause. Statistical analyses were performed in R, version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). The Texas Department of State Health Services’ Center for Health Statistics, per institutional policy, exempted the study from institutional review board approval.

Results

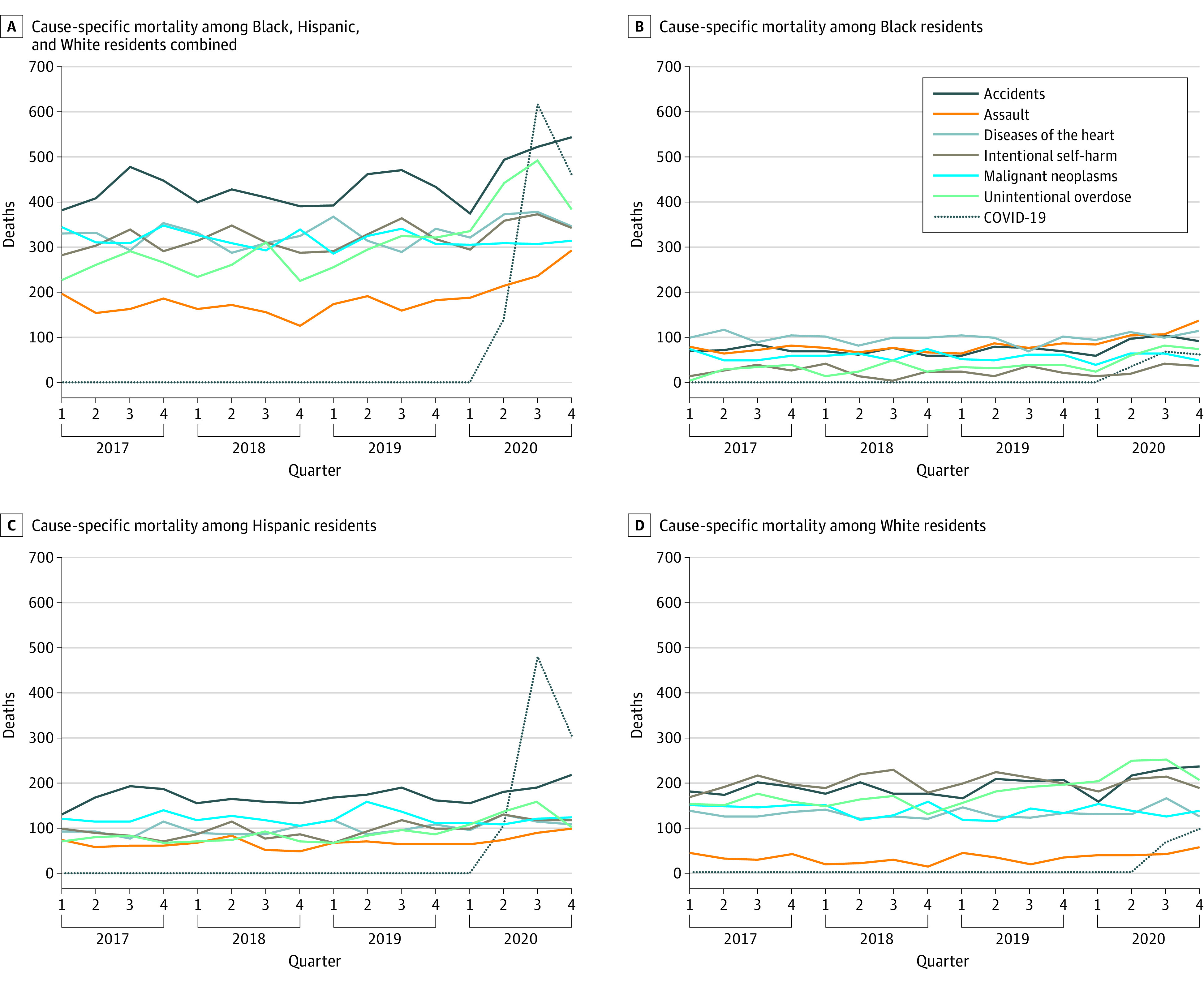

Among Black, Hispanic, and White persons aged 25 to 44 years residing in Texas during March through December 2020, COVID-19 was the leading cause of death during the third quarter of 2020 and the second leading cause during the fourth quarter (Figure, A and Table). During July, November, and December, COVID-19 was the numeric leading cause of death in this combined group (Table). The leading cause of death for March through December 2020 was accidents (Figure, A).

Figure. Cause-Specific Mortality Among Texas Residents Aged 25 to 44 Years, January 2017 Through December 2020.

The solid lines indicate raw cause-specific death counts for usual leading causes of death from January 2017 through December 2020. The dotted dark blue lines indicate raw COVID-19–attributed death counts from March through December 2020.

Table. All-Cause Deaths, Excess Deaths, and Disease-Specific Causes of Death in Texas Residents Aged 25 to 44 Years by Race and Ethnicity, March 1 to December 31, 2020.

| Category | No.a | Incidence rate (95% CI) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths among all races and ethnicitiesb | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | March-December | March-December |

| All ages | ||||||||||||

| All cause | 18 576 | 18 572 | 18 731 | 19 173 | 26 487 | 23 894 | 19 891 | 21 228 | 23 446 | 27 012 | 217 010 | 72.75 (72.45-73.06) |

| COVID-19 | 99 | 934 | 964 | 1435 | 6968 | 5146 | 2341 | 2868 | 5223 | 7556 | 33 534 | 11.24 (11.12-11.36) |

| Aged 25-44 y | ||||||||||||

| Observed | 1045 | 1097 | 1207 | 1272 | 1606 | 1475 | 1190 | 1214 | 1308 | 1401 | 12 815 | 15.35 (15.09-15.62) |

| Expected | 1136 | 911 | 1140 | 914 | 915 | 1146 | 919 | 920 | 1152 | 923 | 10 076 | 12.07 (11.84-12.31) |

| Excess | −91 | 186 | 67 | 358 | 691 | 329 | 271 | 294 | 156 | 478 | 2739 | 3.28 (3.16-3.41) |

| COVID-19 | 2 | 47 | 24 | 92 | 337 | 193 | 106 | 103 | 179 | 220 | 1303 | 1.56 (1.48-1.65) |

| Disease-specific cause, all races and ethnicities | ||||||||||||

| Accidents | 111 | 124 | 180 | 189 | 185 | 198 | 139 | 198 | 160 | 186 | 1670 | 2.00 (1.91-2.10) |

| Assaults | 58 | 75 | 74 | 66 | 94 | 85 | 57 | 90 | 114 | 88 | 801 | 0.96 (0.89-1.03) |

| Diseases of the heart | 119 | 116 | 136 | 121 | 131 | 135 | 112 | 118 | 104 | 124 | 1216 | 1.46 (1.38-1.54) |

| Intentional self-harm | 107 | 106 | 135 | 117 | 132 | 123 | 117 | 106 | 128 | 109 | 1180 | 1.41 (1.33-1.50) |

| Malignant neoplasms | 95 | 91 | 112 | 106 | 109 | 102 | 96 | 103 | 98 | 112 | 1024 | 1.23 (1.15-1.30) |

| Unintentional overdose | 130 | 138 | 154 | 150 | 165 | 175 | 151 | 117 | 124 | 143 | 1447 | 1.73 (1.65-1.83) |

| COVID-19 | 3 | 42 | 21 | 80 | 331 | 186 | 101 | 98 | 164 | 200 | 1226 | 1.47 (1.39-1.55) |

| Disease-specific cause, Black residents | ||||||||||||

| Accidents | 17 | 25 | 36 | 35 | 31 | 34 | 37 | 46 | 21 | 23 | 305 | 2.70 (2.40-3.02) |

| Assaults | 27 | 36 | 40 | 26 | 41 | 41 | 24 | 49 | 45 | 42 | 371 | 3.28 (2.95-3.63) |

| Diseases of the heart | 30 | 39 | 38 | 33 | 32 | 40 | 27 | 40 | 38 | 36 | 353 | 3.12 (2.80-3.46) |

| Intentional self-harm | 10 | 1 | 16 | 1 | 12 | 12 | 16 | 12 | 10 | 14 | 104 | 0.92 (0.75-1.11) |

| Malignant neoplasms | 13 | 17 | 23 | 22 | 22 | 18 | 22 | 17 | 16 | 16 | 186 | 1.64 (1.42-1.90) |

| Unintentional overdose | 13 | 18 | 19 | 21 | 22 | 31 | 27 | 17 | 30 | 27 | 225 | 1.99 (1.74-2.27) |

| COVID-19 | 1 | 16 | 1 | 14 | 43 | 12 | 10 | 13 | 16 | 34 | 160 | 1.41 (1.20-1.65) |

| Disease-specific cause, Hispanic residents | ||||||||||||

| Accidents | 45 | 44 | 64 | 74 | 68 | 83 | 38 | 66 | 73 | 79 | 634 | 1.84 (1.70-1.99) |

| Assaults | 20 | 24 | 23 | 28 | 35 | 22 | 32 | 24 | 45 | 30 | 283 | 0.82 (0.73-0.92) |

| Diseases of the heart | 34 | 34 | 55 | 43 | 45 | 36 | 33 | 42 | 32 | 34 | 388 | 1.13 (1.02-1.24) |

| Intentional self harm | 38 | 35 | 53 | 44 | 42 | 37 | 39 | 35 | 45 | 38 | 406 | 1.18 (1.07-1.30) |

| Malignant neoplasms | 35 | 33 | 42 | 35 | 40 | 40 | 41 | 42 | 41 | 43 | 392 | 1.14 (1.03-1.26) |

| Unintentional overdose | 44 | 41 | 43 | 52 | 65 | 53 | 42 | 35 | 33 | 35 | 443 | 1.29 (1.17-1.41) |

| COVID-19 | 1 | 25 | 19 | 65 | 258 | 156 | 69 | 69 | 112 | 122 | 896 | 2.60 (2.43-2.78) |

| Disease-specific cause, White residents | ||||||||||||

| Accidents | 49 | 55 | 80 | 80 | 86 | 81 | 64 | 86 | 66 | 84 | 731 | 2.30 (2.14-2.48) |

| Assaults | 11 | 15 | 11 | 12 | 18 | 22 | 1 | 17 | 24 | 16 | 147 | 0.46 (0.39-0.54) |

| Diseases of the heart | 55 | 43 | 43 | 45 | 54 | 59 | 52 | 36 | 34 | 54 | 475 | 1.50 (1.36-1.64) |

| Intentional self-harm | 59 | 70 | 66 | 72 | 78 | 74 | 62 | 59 | 73 | 57 | 670 | 2.11 (1.95-2.28) |

| Malignant neoplasms | 47 | 41 | 47 | 49 | 47 | 44 | 33 | 44 | 41 | 53 | 446 | 1.40 (1.28-1.54) |

| Unintentional overdose | 73 | 79 | 92 | 77 | 78 | 91 | 82 | 65 | 61 | 81 | 779 | 2.45 (2.28-2.63) |

| COVID-19 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 30 | 18 | 22 | 16 | 36 | 44 | 170 | 0.54 (0.46-0.62) |

Cells with 1 reported indicate that between 1 and 9 deaths were reported but the exact value was suppressed by the Texas Department of State Health Services.

Deaths for all races and ethnicities were obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics (https://data.cdc.gov/NCHS/Provisional-COVID-19-Deaths-by-Place-of-Death-and-/4va6-ph5s).

Among Black individuals aged 25 to 44 years, COVID-19 was the sixth leading cause of death from March through December 2020 (Figure, B), though in July COVID-19 was numerically the leading cause of death (Table). The leading causes of death were assault, diseases of the heart, and accidents (Figure, B and Table).

Among Hispanic individuals aged 25 to 44 years, COVID-19 was the leading cause of death from March through December 2020 (Figure, C and Table) and during the third and fourth quarters of 2020. During the third quarter, more COVID-19–attributed deaths were recorded among Hispanic individuals aged 25 to 44 years than for the next 2 most-common causes combined (accidents and unintentional overdoses).

Among White individuals aged 25 to 44 years, COVID-19 was the sixth leading cause from March through December 2020 (Figure, D). The leading causes of death were unintentional overdoses and accidents (Figure, D and Table).

Discussion

Results of this cohort study demonstrated that during March through December 2020, the first 10 months of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US, COVID-19 was the second leading cause of death among Black, Hispanic, and White residents of Texas aged 25 to 44 years, and the most common cause during the third quarter of 2020, with a markedly disproportionate increase in mortality among Hispanic residents. One possible explanation may be that Hispanic persons were more likely to be essential workers and, therefore, were less able to avoid exposure to SARS-CoV-2, which has previously been linked to socioeconomic factors.5,6 Another possible explanation is that Hispanic residents were less likely to have access to primary care and, therefore, more likely to experience unmanaged medical comorbidities associated with worse COVID-19 outcomes. Limitations of this study include the accuracy of data from death certificates and the preliminary nature of 2020 data. Nevertheless, these findings highlight the markedly disparate effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in different populations of young adults, particularly among Hispanic residents of Texas.

eAppendix.

References

- 1.Rossen LM, Branum AM, Ahmad FB, Sutton P, Anderson RN. Excess deaths associated with COVID-19, by age and race and ethnicity—United States, January 26–October 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(42):1522-1527. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6942e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simon P, Ho A, Shah MD, Shetgiri R. Trends in mortality from COVID-19 and other leading causes of death among Latino vs White individuals in Los Angeles County, 2011-2020. JAMA. 2021;326(10):973-974. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.11945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faust JS, Krumholz HM, Du C, et al. All-cause excess mortality and COVID-19–related mortality among US adults aged 25-44 years, March-July 2020. JAMA. 2021;325(8):785-787. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.24243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Center for Health Statistics. Weekly counts of deaths by jurisdiction and age. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Updated October 13, 2021. Accessed October 18, 2021. https://data.cdc.gov/NCHS/Weekly-Counts-of-Deaths-by-Jurisdiction-and-Age/y5bj-9g5w

- 5.Chen Y-H, Glymour MM, Catalano R, et al. Excess mortality in California during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, March to August 2020. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(5):705-707. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.7578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y-H, Glymour M, Riley A, et al. Excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic among Californians 18-65 years of age, by occupational sector and occupation: March through November 2020. PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0252454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix.