Abstract

Introduction

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) on biologic therapy may lose response to anti-tumor necrosis factor agents (anti-TNFs) due to the development of anti-drug antibodies (ADAs). A history of anti-TNF ADA increases the risk of developing ADA to subsequent anti-TNFs; however, it is not known whether ADA to anti-TNFs increases the risk of ADA development to vedolizumab (VDZ) or ustekinumab (UST). We aimed to investigate whether prior history of ADA to anti-TNF increases the risk of ADA to VDZ and UST.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients at a tertiary care IBD center over the course of four years who had previous anti-TNF drug and ADA level data during maintenance treatment and subsequent VDZ or UST drug and antibody levels, all collected as standard of care. The primary outcome was the rate of ADA development to VDZ and UST in patients with and without prior anti-TNF immunogenicity. Descriptive statistics summarized the data and univariate tested associations.

Results

Of the 152 IBD patients analyzed, 41 (27%) had a history of previous anti-TNF ADA with 22 (53.7%) having simultaneously undetectable anti-TNF drug levels. There was no significant difference in the rates of ustekinumab and vedolizumab ADA development between patients with prior ADA and patients without prior ADA (1/41 [2.7%] vs 1/111 [0.9%]; p = 0.54). There was also no difference in concomitant immunomodulator use with ustekinumab or vedolizumab initiation in patients with or without prior ADA (13/41 [31.7%] vs 31/111 [27.9%], p = 0.84). Neither patient who developed ADA to VDZ or UST was on concomitant immunomodulator at drug initiation, and both patients had detectable drug levels at the time of antibody detection.

Conclusions

We observed that prior immunogenicity to anti-TNF agents does not confer an increased risk of immunogenicity to ustekinumab or vedolizumab. Our data support the use of vedolizumab or ustekinumab as monotherapy for the treatment of IBD.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s disease, Ulcerative colitis, Immunogenicity, Ustekinumab, Vedolizumab

Introduction

Monoclonal antibodies directed against tumor necrosis factor alpha (anti-TNF) remain a mainstay of treatment for patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). While anti-TNF agents are effective treatment modalities for many patients, approximately 30% of patients show primary non-response (PNR) to anti-TNF agents during induction therapy, and an additional 30–50% of patients will show secondary loss of response (SLR) during maintenance [1]. The formation of anti-drug antibodies (ADA) against anti-TNF agents plays a major role in both PNR and SLR.

Circulating ADA may bind to anti-TNF agents and result in rapid clearance of the drug [2, 3]. Rates of immunogenicity against anti-TNF agents are significant, with some observational studies reporting rates as high as 65% patients receiving infliximab (IFX) and 38% in patients receiving adalimumab [1]. A recent study by Yanai et al. showed that nearly 40% of IBD patients with immunogenicity toward an initial anti-TNF agent will develop immunogenicity toward subsequent anti-TNFs [4].

Vedolizumab (VDZ) and ustekinumab (UST) are two monoclonal antibodies with novel mechanisms that have also been shown to be effective in the treatment of IBD [5–8]. Unlike anti-TNFs, currently published data suggest that concomitant immunomodulator therapy with VDZ or UST does not improve clinical outcomes or pharmacokinetics. A retrospective cohort study by Hu et al. showed that concomitant immunomodulator therapy with VDZ or UST did not improve rates of clinical or endoscopic response at one year compared to monotherapy [9]. Additionally, subgroup analyses from the pivotal trials of these agents failed to show a clinical benefit from concomitant immunomodulator therapy [5–9]. Studies have also shown that unlike anti-TNFs, concomitant immunomodulator therapy with VDZ and UST does not increase trough levels compared to monotherapy [10, 11].

The rates of ADA development to VDZ (ATV) and UST (ATU) reported in their respective landmark trials are significantly lower than those of anti-TNF agents. The rates of ATU formation seen in the UNITI and UNIFI trials were 2.3% and 4.6% at 52 weeks, while the reported rates of ATV formation at 52 weeks in the GEMINI trials were 4.1% and 3.7%, respectively [5–8]. However, it is still plausible that immunogenicity may play a role in PNR and SLR to these agents. To our knowledge, there are no currently published data exploring whether prior immunogenicity to anti-TNF is associated with an increase in ATV and ATU development. We sought to investigate whether a history of immunogenicity toward anti-TNF agents is associated with an increased risk of subsequent immunogenicity to VDZ or UST.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of all pediatric and adult IBD patients at a single tertiary referral center who had anti-TNF drug and ADA levels with subsequent VDZ or UST drug and ADA levels checked during maintenance as part of standard care. All drug and ADA levels were run using a homogenous mobility shift assay (Prometheus Biosciences, San Diego, CA) [14]. We collected demographic data including age, gender, race, IBD subtype, age at diagnosis, disease location, disease behavior, number of previous anti-TNF agents used, and concomitant immunomodulator use at VDZ or UST initiation. We defined “immunogenicity” as any detectable level of ATV or ATU.

The primary outcome was the frequency of immunogenicity to VDZ or UST. We compared the proportion of patients with immunogenicity to VDZ or UST stratified by prior anti-TNF immunogenicity status. Secondary outcomes assessed included the percentage of patients who had undetectable VDZ or UST levels at the time of ATV or ATU detection. Descriptive statistics were performed using proportions and medians [interquartile range, (IQR)], and comparisons between groups were done using Fisher’s exact tests.

Results

Of the 152 patients who met our prespecified study criteria, the median age was 24.5 [22] years and the median disease duration was 6 [9] years (Table 1). Over half (55%) of patients had Crohn’s disease, and the median number of prior anti-TNF agents was 1 [1]. There were 41 patients (27%) with detectable anti-TNF ADA of whom 22 (53.7%) had undetectable anti-TNF drug levels. The median anti-TNF drug level was 9.8 μg/mL [17.2], and median anti-TNF ADA level was 10.9 U/mL [39]. The median time on drug prior to VDZ and UST drug and ADA level assessment was 11 [11] and 7 [9] months, respectively.

Table 1.

Cohort demographics, stratified by previous anti-TNF exposure

| Category | All (N = 152) | No prior immunogenicity (N = 111) | Prior anti-TNF immunogenicity (N = 41) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crohn’s disease, N (%) | 84 (55.2) | 60 (54.1) | 24 (58.5) |

| Male, N (%) | 75 (49.3) | 57 (51.4) | 18 (43.9) |

| Caucasian, N (%) | 131 (86.2) | 98 (88.3) | |

| Age, median years (IQR) | 24.5 (22) | 24 (22) | 26 (15) |

| Disease duration, median years (IQR) | 6 (9) | 5 (9) | 8 (6) |

| Disease behavior | |||

| Non-penetrating/non-stricturing (B1), N (%) | 47 (56) | 33 (55) | 14 (58.3) |

| Stricturing (B2), N (%) | 17 (20.2) | 11 (18.3) | 6 (25) |

| Penetrating (B3), N (%) | 13 (15.5) | 10 (16.7) | 3 (12.5) |

| Stricturing/penetrating (B2, B3), N (%) | 7 (8.3) | 6 (10) | 1 (4.2) |

| Disease location (CD) | |||

| Ileal ( L1), N (%) | 13 (15.5) | 11 (18.4) | 2 (8.3) |

| Colonic (L2), N (%) | 21 (23.8) | 15 (25) | 6 (25) |

| Ileocolonic (L3), N (%) | 45 (53.6) | 32 (53.3) | 13 (54.2) |

| Upper tract (L4), N (%) | 34 (40.5) | 20 (33.3) | 14 (58.3) |

| Disease location (UC) | |||

| Proctitis (E1), N (%) | 5 (9.1) | 2 (4.8) | 3 (23.1) |

| Left-sided (E2), N (%) | 16 (29.1) | 14 (33.3) | 2 (15.4) |

| Pancolitis, N (%) | 34 (61.8) | 26 (61.9) | 8 (61.5) |

| IBDU, N (%) | 13 (8.6) | 9 (8.1) | 4 (9.8) |

| Perianal involvement, N (%) | 26 (31) | 19 (31.7) | 7 (29.2) |

| Concomitant immunomodulator with VDZ/UST, N (%)* | 44 (28.9) | 31 (27.9) | 13 (31.7) |

| Number of prior anti-TNFs, median (IQR) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Anti-TNF ADA Level (U/mL), median (IQR) | – | – | 10.9 (39) |

| *p = 0.84 | – | – | – |

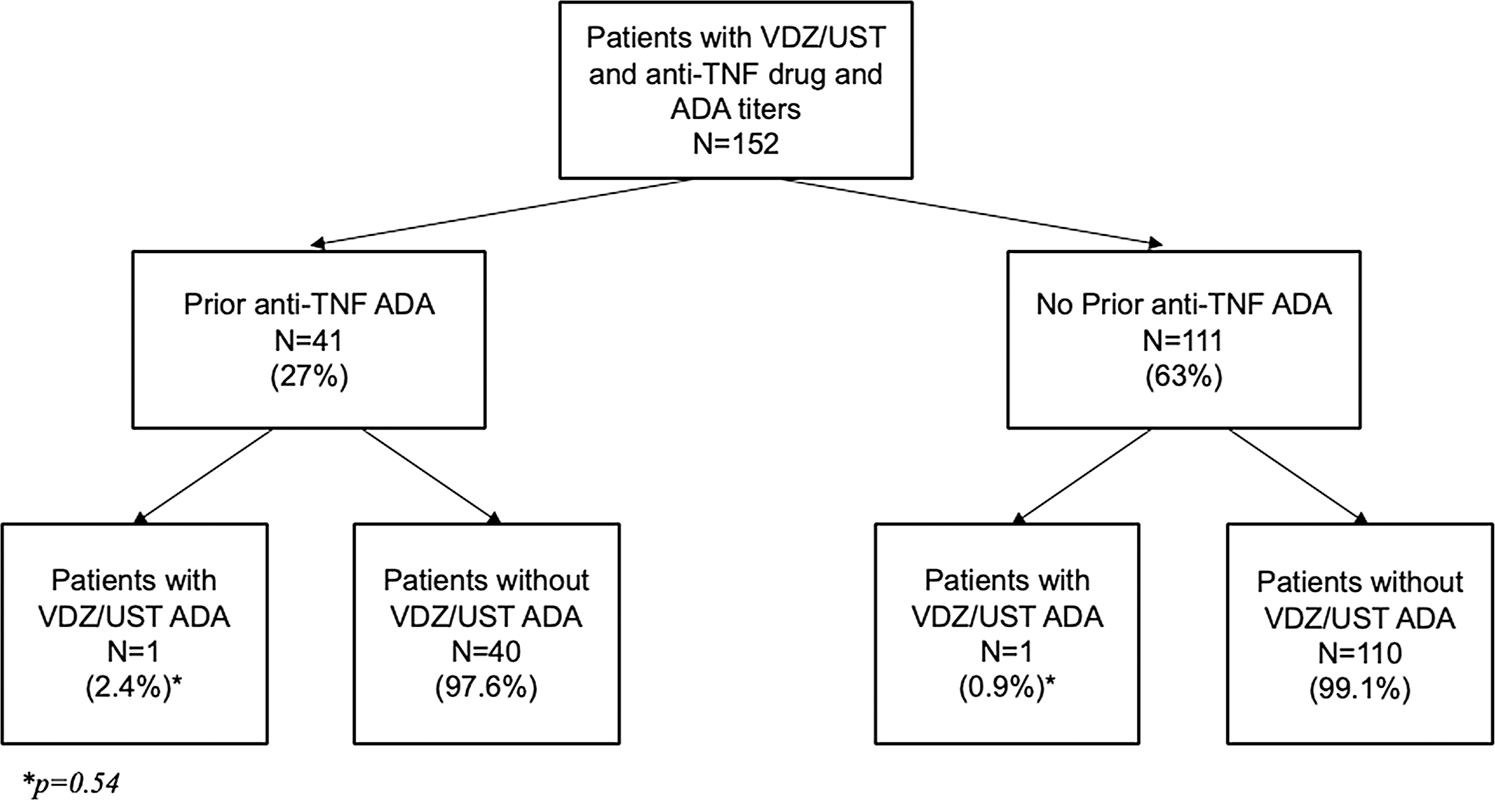

There were no significant differences in the rates of ATV or ATU formation among patients with and without a history of anti-TNF immunogenicity (1/41 [2.7%] vs 1/111 [0.9%]; p = 0.54) (Fig. 1). Forty-four (29.1%) patients were on concomitant immunomodulator therapy during VDZ or UST induction, and 24 (54.5%) of these patients were on concomitant immunomodulator therapy at the time levels were checked. There was no significant difference in concomitant immunomodulator use at time VDZ or UST initiation in patients with and without prior anti-TNF immunogenicity (13/41 [31.7%] vs 31/111 [27.9%], p = 0.84). There were no significant differences in the mean concentrations of VDZ (18.1 μg/mL vs 17.7 μg/mL, p = 0.89) or UST (9.4 μg/mL vs 8.1 μg/mL, p = 0.72) in patients on concomitant immunomodulator therapy compared to those on monotherapy.

Fig. 1.

Proportion of patients with prior anti-TNF anti-drug antibodies (ADA) with ADA against vedolizumab or ustekinumab

One patient with prior anti-TNF immunogenicity developed ATV, and one patient without prior anti-TNF immunogenicity developed ATU. Both patients had detectable drug levels at the time of ATV and ATU detection. The patient who developed ATV had a drug level of 33.8 μg/mL with an ATV level of 7.1 U/mL, while the patient who developed ATU had a drug level of 7.3 μg/mL with an ATU level of 2.3 U/mL. Neither patient was on concomitant immunomodulator therapy at the time of ADA detection.

Both patients with detectable antibodies exhibited SLR at the time of antibody detection despite having detectable drug levels. The patient who developed ATV had moderate clinical symptoms based on physician assessment at the time of ATV detection and VDZ was subsequently discontinued. The patient who developed ATU was in clinical remission at the time of ADA detection, but had persistently elevated inflammatory markers and endoscopic disease on subsequent assessment. The patient was continued on UST with dose escalation to every four weeks. Repeat drug levels and ATU nine months after ATU detection showed no detectable ATU with detectable drug levels.

Discussion

In our retrospective cohort study of 152 IBD patients, we observed that patients with a prior history of immunogenicity to anti-TNF agents are not at an increased risk of subsequent immunogenicity to VDZ or UST compared to patients without a prior history of anti-TNF immunogenicity. Previous studies have shown as many as 40% of patients who develop immunogenicity to an initial anti-TNF agent will go on to develop immunogenicity to subsequent anti-TNFs [4, 13]. However, our study suggests that this increased risk of subsequent immunogenicity may not apply to other classes of biologic agents.

Our data also provide additional support that concomitant immunomodulator use with initiation of VDZ or UST may be of limited value. Several studies have demonstrated greater efficacy and lower rates of immunogenicity in patients treated with combination IFX and azathioprine compared to IFX or azathioprine monotherapy [14, 15]. Hu et al. showed that unlike with anti-TNF agents, concomitant immunomodulator therapy with VDZ or UST does not result in improved rates of clinical or endoscopic response compared to VDZ or UST monotherapy [9]. Our study provides additional information that concomitant immunomodulator therapy neither reduces the rates of immunogenicity to VDZ or UST, nor significantly affects mean drug concentration compared to monotherapy.

The clinical significance of detectable ADA in patients with detectable drug levels is unclear; however, both patients did exhibit evidence of SLR at the time of ADA detection. The implication of detectable ATV and ATU in the presence of detectable drug levels is not entirely clear, but prior studies investigating this same issue in IFX suggest that this may be associated with greater risk of SLR [16]. An expert consensus on therapeutic drug monitoring by Papamichael et al. concluded that there is currently insufficient evidence to recommend a “high” ADA titer for non-IFX biologics [16]. Future studies should be aimed at investigating whether the presence of ATV and ATU is associated with PNR and SLR, as well as clinically meaningful titers of these antibodies.

Our study has several strengths. We utilized a large tertiary care center population with all drug and ADA levels measured using the homogenous mobility shift assays capable of detecting ADA in the presence of detectable VDZ or UST [12]. The rates of immunogenicity to anti-TNFs, VDZ, and UST seen in our study are also consistent with those reported in landmark trials [5–8]. Our study also has several limitations. First, our study is retrospective in design, which inherently increases the risk of selection bias. Second, our analysis was limited by the sample size and low event rate of ATV and ATU development over our prespecified timeframe. The low number of events precluded multivariable analysis, and subsequent studies with larger cohorts are necessary to confirm our findings. Finally, our study population was comprised of a largely Caucasian population, which may limit the generalizability to other ethnic groups.

In conclusion, our study provides initial data that prior history of anti-TNF immunogenicity does not confer an increased risk of immunogenicity against VDZ or UST in patients with IBD. These data support the use of VDZ and UST as monotherapy in the treatment of IBD.

Funding

This project was not funded.

Conflict of interest Nicholas Costable declares no conflicts of interests. Zachary Borman declares no conflicts of interests. Jiayi Ji declares no conflicts of interest. Marla Dubinsky is a consultant and research support for Prometheus Biosciences, Janssen, Abbvie. Ryan Ungaro is an advisory board member or consultant for Eli Lilly, Janssen, Pfizer, and Takeda and research support from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Pfizer. RCU is funded by a NIH K23 Career Development Award (K23KD111995–01A1).

Footnotes

Human participants Our study involves the use of previously acquired medical information from human subjects. Our study protocol, including study design and methods of data collection, was approved by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Institutional Review Board (IRB), and our manuscript contains no patient identifiers. As our study was retrospective in nature, formal consent from participants was deemed impractical and as such was not required for IRB approval.

Reference

- 1.Vermeire Séverine, et al. “Immunogenicity of biologics in inflammatory bowel disease.” Therapeutic advances in gastroenterology. 11 (2018): 1756283X17750355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vincent Fabien B., et al. “Antidrug antibodies (ADAb) to tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-specific neutralising agents in chronic inflammatory diseases: a real issue, a clinical perspective.” Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 72.2 (2013): 165–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van der Laken CJ et al. Imaging and serum analysis of immune complex formation of radiolabelled infliximab and anti-infliximab in responders and non-responders to therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases 2007;66:253–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yanai Henit, et al. “INCREASED RISK OF ANTI-DRUG ANTIBODIES TO A SECOND ANTI TNF IN PATIENTS WHO DEVELOPED ANTIBODIES TO THE FIRST ANTI TNF.” JOURNAL OF CROHNS & COLITIS. Vol. 14. GREAT CLARENDON ST, OXFORD OX2 6DP, ENGLAND: OXFORD UNIV PRESS, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sands Bruce E., et al. “Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis.” New England Journal of Medicine 381.13 (2019): 1201–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feagan Brian G., et al. “Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease.” New England Journal of Medicine 375.20 (2016): 1946–1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feagan Brian G., et al. “Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis.” New England Journal of Medicine 369.8 (2013): 699–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandborn William J., et al. “Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease.” New England Journal of Medicine. 369.8 (2013): 711–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu Anne, et al. “Combination therapy does not improve rate of clinical or endoscopic remission in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases treated with vedolizumab or ustekinumab.” Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ungaro Ryan C., et al. “Higher trough vedolizumab concentrations during maintenance therapy are associated with corticosteroid-free remission in inflammatory bowel disease.” Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis. 13.8 (2019): 963–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adedokun Omoniyi J., et al. “Ustekinumab pharmacokinetics and exposure response in a phase 3 randomized trial of patients with ulcerative colitis.” Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 18.10 (2020): 2244–2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Shui-Long, et al. “Development and validation of a homogeneous mobility shift assay for the measurement of infliximab and antibodies-to-infliximab levels in patient serum.” Journal of immunological methods. 382.1–2 (2012): 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frederiksen Madeline Therese, et al. “Antibodies against infliximab are associated with de novo development of antibodies to adalimumab and therapeutic failure in infliximab-to-adalimumab switchers with IBD.” Inflammatory bowel disease. 20.10 (2014): 1714–1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colombel Jean Frédéric, et al. “Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease.” New England Journal of Medicine. 362.15 (2010): 1383–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panaccione Remo, et al. “Combination therapy with infliximab and azathioprine is superior to monotherapy with either agent in ulcerative colitis.” Gastroenterology. 146.2 (2014): 392–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papamichael Konstantinos, et al. “Appropriate therapeutic drug monitoring of biologic agents for patients with inflammatory bowel diseases.” Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 17.9 (2019): 1655–1668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]