Abstract

Background:

Istradefylline is a selective adenosine A2A receptor antagonist for the treatment of patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) experiencing OFF episodes while on levodopa/decarboxylase inhibitor.

Objective:

This pooled analysis of eight randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 2b/3 studies evaluated the efficacy and safety of istradefylline.

Methods:

Istradefylline was evaluated in PD patients receiving levodopa with carbidopa/benserazide and experiencing motor fluctuations. Eight 12- or 16-week trials were conducted (n = 3,245); four of these studies were the basis for istradefylline’s FDA approval. Change in OFF time as assessed in patient-completed 24-h PD diaries at Week 12 was the primary endpoint. All studies were designed with common methodology, thereby permitting pooling of data. Pooled analysis results from once-daily oral istradefylline (20 and 40 mg/day) and placebo were evaluated using a mixed-model repeated-measures approach including study as a factor.

Results:

Among 2,719 patients (placebo, n = 992; 20 mg/day, n = 848; 40 mg/day, n = 879), OFF hours/day were reduced at Week 12 at istradefylline dosages of 20 mg/day (least-squares mean difference [LSMD] from placebo in reduction from baseline [95%CI], –0.38 h [–0.61, –0.15]) and 40 mg/day (–0.45 h [–0.68, –0.22], p < 0.0001); ON time without troublesome dyskinesia (ON-WoTD) significantly increased. Similar results were found in the four-study pool (OFF hours/day, 20 mg/day, –0.75 h [–1.10, –0.40]; 40 mg/day, –0.82 h [–1.17, –0.47]). Istradefylline was generally well-tolerated; the average study completion rate among istradefylline-treated patients across all studies was 89.2%. Dyskinesia was the most frequent adverse event (placebo, 9.6%; 20 mg/day, 16.1%; 40 mg/day, 17.7%).

Conclusion:

In this pooled analysis, istradefylline significantly improved OFF time and ON-WoTD relative to placebo and was well-tolerated.

Keywords: Adenosine 2A receptor antagonist, istradefylline, Parkinson’s disease, treatment

INTRODUCTION

Levodopa is the cornerstone of treatment for patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) and generally provides good symptom relief; however, the duration of efficacy (ON time) commonly becomes shorter and increasingly variable over time. In addition, patients experience delays in the onset of benefit. Consequently, many patients start experiencing daily periods during which symptoms return and levodopa does not adequately control symptoms (OFF time) [1]. Current adjunctive, dopaminergic therapies, such as dopamine agonists (DAs) and COMT and MAO-B inhibitors, reduce but do not fully eliminate motor fluctuations. Furthermore, adjunctive dopaminergic therapies may be accompanied by dose-limiting adverse events (AEs), including dyskinesia, drowsiness, nausea, orthostatic hypotension, hallucinations, peripheral edema, and impulse control disorders [2, 3].

Istradefylline is a nondopaminergic medication that is adjunctive treatment to levodopa in combination with an aromatic amino acid decarboxylase inhibitor in adult patients with PD experiencing OFF episodes [4–6]. A selective adenosine A2A receptor antagonist, istradefylline has a xanthine chemical structure and does not interact with dopamine receptors or alter dopamine metabolism; it has low or very weak affinity for other receptors, transporters, and ion channels, such as serotonin and acetylcholine receptors as well as other adenosine receptor subtypes [7].

Most treatments for patients with PD help counter the reduction in striatal dopaminergic stimulation that is central to the disease process. Istradefylline, by contrast, targets adenosine A2A receptors, which are highly localized in parts of the basal ganglia, including the caudate nucleus, putamen, and nucleus accumbens [8–12].

In PD, istradefylline is thought to act via the indirect striatal output pathway of the basal ganglia, which suppresses movement. This pathway, which is excessively activated in PD because of loss of dopamine D2 receptor-mediated inhibitory effect, is known to be regulated by the A2A receptor-mediated excitatory mechanism [10]. Istradefylline blocks adenosine A2A receptors in the striatum and globus pallidus external segment, reducing the excessive output of the indirect pathway that occurs in PD. Consequently, the imbalance between the indirect and direct pathways of the basal ganglia is reduced [6].

Istradefylline has been evaluated in multiple phase 2 and 3 studies [13–19]. In levodopa-treated adults with PD experiencing motor fluctuations, studies have demonstrated that istradefylline was generally well-tolerated, reduced OFF time, and increased ON time without troublesome dyskinesia relative to placebo [13, 15–18]. Previous meta-analyses have suggested that, compared to placebo, istradefylline reduces OFF time and motor symptoms, whereas rates of dyskinesia may increase with treatment [20, 21].

Here, we present individual and pooled analyses of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials in which istradefylline or placebo was added onto stable therapy with levodopa with or without other anti-Parkinson medications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

Eight 12- or 16-week phase 2b/3 randomized clinical trials were conducted in North America, Japan, or internationally (NCT00199394, NCT00199407, NCT00199420, NCT00455507, NCT00456586, NCT00456794, NCT00955526, NCT01968031; Supplementary File 1,Supplementary Table 1). All study sites had local or central Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, and research was carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki as currently amended. Six of these studies have been published previously in peer-reviewed literature [13–18]. In total, 3,245 patients were randomized to receive once-daily oral doses of placebo or istradefylline (10, 20, 40, or 60 mg) or multiple daily doses of entacapone (200 mg/dose). Entacapone and istradefylline 10 and 60 mg were evaluated in one study each; istradefylline at 20 mg (6002-US-006, 6002-US-013, 6002-0608, 6002-009, 6002-US-018, and 6002-014) and 40 mg (6002-US-005, 6002-0608, 6002-009, 6002-US-018, 6002-EU-007, 6002-014) per dose [13, 14] were evaluated in six studies each ( Supplementary File 1, Supplementary Table 1). Only the placebo and 20 and 40 mg istradefylline treatment groups were selected to be pooled in the present analysis and to be compared with placebo, as the 20 and 40 mg doses are the doses approved for use in clinical practice (Supplementary File 1, Supplementary Figure 1).

Data from all eight randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were pooled for efficacy and safety analyses. A second analysis was performed in which data were pooled from the four studies that were selected by the regulatory authority in the United States for istradefylline’s approval. This analysis is presented to enable readers to better interpret and understand the US product label; these four studies represent the trials that met their primary endpoints by the pre-specified analysis method [4]. All studies were specifically designed to have common methodology ( Supplementary File 1, Supplementary Table 2), thus permitting pooling of all 8 studies.

Patients

Eligible patients were ≥30 years old (≥20 years old in 6002-0608 [17] and 6002-009 [18]) and were diagnosed with idiopathic PD based on the United Kingdom Parkinson’s Disease Society (UKPDS) Brain Bank Diagnostic Criteria with a Modified Hoehn and Yahr stage of 2 to 4 in the OFF state (ON state in 6002-014).

Patients received levodopa in combination with carbidopa or benserazide for ≥1 year prior to study entry, were on a stable levodopa regimen for ≥4 weeks prior to randomization, and were experiencing end-of-dose wearing-off with an average of at least 2 (Studies 6002-US-005, 6002-US-006, 6002-0608, 6002-009, and 6002-014) [13, 16–18] or 3 h OFF time/day (Studies 6002-US-013, 6002-US-018, and 6002-EU-007) [14, 15] at baseline (see Supplementary File 1, Supplementary Table 2). Levodopa dosages could be reduced if patients experienced levodopa-related AEs (6002-US-018, 6002-0608, and 6002-009), AEs (6002-US-005, 6002-US-006, and 6002-US-013), or dopamine-related AEs (6002-EU-007) but could not be increased above baseline. Dose changes were not permitted in 6002-014. Patients continued concomitant treatment with other approved anti-Parkinson medications at stable dosages.

Primary endpoints and analysis sets for study endpoints

OFF and ON time recorded in patient-completed 24-h PD diaries provided the primary and secondary change-from-baseline endpoints [22]. The presence of pre-existing dyskinesia was determined using diary records from the week preceding the baseline visit. Change from baseline to Week 12 or End-of-Study in daily OFF time was the primary endpoint of all studies and was reported as either percentage of awake time (%OFF) or hours/day (hours OFF; Supplementary File 1, Supplementary Table 1). In studies where the primary endpoint was recorded as a percentage, data were expressed as hours/day for pooling. Istradefylline had no placebo-adjusted effect on hours asleep/day. Therefore, interconversion of OFF time between percentage of awake time and hours/day permits assessment of statistically significant differences between groups.

ON time was recorded in diaries as occurring with or without dyskinesia. ON time with dyskinesia was reported as non-troublesome (did not interfere with function or cause meaningful discomfort) or troublesome (interfered with function or caused meaningful discomfort) [22]. The sum of ON time without dyskinesia plus ON time with non-troublesome dyskinesia provided the derived variable of ON time without troublesome dyskinesia. Overall, the following parameters were evaluated: total ON time, ON time without dyskinesia, ON time with troublesome dyskinesia, and ON time without troublesome dyskinesia.

Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) Part II and III scores in the ON state were recorded in all trials. The Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 20.0 was used to classify all AEs reported during the study by System Organ Class and preferred term.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were summarized by number of patients, mean, standard deviation (SD), median, minimum, and maximum values. Categorical variables were summarized by number and percentage of patients in each category.

In the pooled analysis, the primary efficacy endpoint was evaluated using a mixed-effect model for repeated measures (MMRM) approach with baseline value as a covariate; fixed-effect terms in the model for study, pooled study center, treatment group, week, and treatment-by-week interaction; and an unstructured covariance matrix. Using this model, the differences in change from baseline to Week 12 for the primary and key secondary efficacy endpoints between each istradefylline treatment group and placebo were estimated based on least-squares (LS) mean difference, with corresponding 95%confidence intervals (CIs) and p values. The LS mean and corresponding 95%CI for the change from baseline to Week 12 for 20 mg, 40 mg and placebo were also estimated from the MMRM. Incidences of treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) were summarized by preferred term (MedDRA version 20.0) using the number and percentage of patients reporting an event.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics and demographics

There were 3245 patients in the eight studies evaluated, including patients who received 10 mg/day istradefylline (n = 149), 60 mg/day istradefylline (n = 155), and entacapone (n = 146). To evaluate approved dosages of istradefylline vs placebo, the pooled population (N = 2719) comprised those patients in the placebo (n = 992), istradefylline 20 mg/day (n = 848), and istradefylline 40 mg/day (n = 879) treatment groups ( Supplementary File 1, Supplementary Table 1).

Demographic variables were balanced among treatment groups within each study. Table 1 shows the similarities across studies in intent-to-treat (ITT) populations. Results from the two previously unpublished trials (6002-EU-007 and 6002-014) are shown in Supplementary Files 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and demographicsa

| Characteristic | Study No. 6002- | |||||||

| US-005 | US-006 | US-013 | 0608 | 009 | US-018 | EU-007 | 6002-014 | |

| Age (y), n | 195 | 395 | 225 | 357 | 366 | 584 | 455 | 592 |

| Mean (SD) | 63 (9) | 64 (10) | 63 (10) | 65 (8) | 66 (9) | 63 (9) | 62 (9) | 64 (8) |

| [range] | [38–87] | [36–87] | [36–87] | [37–84] | [33–84] | [35–85] | [34–87] | [41–87] |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||||

| Male | 117 (60) | 264 (67) | 150 (67) | 150 (42) | 162 (44) | 389 (67) | 278 (61) | 363 (61) |

| BMI (kg/m2), n | 195 | 394 | 225 | 357 | 366 | 582 | 455 | 592 |

| Mean (SD) | 26.7 (5.2) | 26.3 (4.5) | 27.0 (5.2) | 21.9 (3.4) | 22.3 (3.5) | 28.1 (5.4) | 25.3 (4.3) | 27.2 (4.9) |

| [range] | [17.8–57.2] | [15.9–45.4] | [17.2–44.9] | [13.8–32.5] | [14.2–40.0] | [15.7–54.4] | [14.4–45.2] | [16.3–46.5] |

| Total OFF time, (hours/day)b, n | 195 | 395 | 225 | 357 | 366 | 584 | 455 | 592 |

| Mean (SD) | 6.3 (2.6) | 5.9 (2.5) | 6.6 (2.5) | 6.6 (2.7) | 6.3 (2.6) | 6.7 (2.1) | 6.4 (2.2) | 5.4 (2.0) |

| [range] | [0.0–14.5] | [0.8–14.8] | [2.5–17.8] | [2.0–17.0] | [1.9–14.2] | [2.0–16.3] | [2.0–14.0] | [1.0–14.3] |

| Total daily dose of levodopa at study entry (mg), n | 195 | 390 | 224 | 357 | 366 | 584 | 454 | 592 |

| Median | 700 | 700 | 700 | 400 | 400 | 750 | 600 | 750 |

| [range] | [150–4800] | [75–2200] | [150–2100] | [300–1500] | [300–1200] | [25–3000] | [105–2000] | [300–3150] |

| UPDRS Part III scorec in the ON state, n | 182 | 388 | 219 | 357 | 366 | 558 | 444 | 592 |

| Mean (SD) | 17.8 (11.1) | 17.0 (9.4) | 23.4 (11.2) | 20.9 (10.3) | 21.2 (11.1) | 22.1 (11.4) | 27.5 (11.8) | 22.7 (11.5) |

| Time since PD diagnosis, y, n | 195 | 395 | 225 | 357 | 366 | 584 | 454 | –d |

| Mean (SD) | 9.9 (5.0) | 9.5 (5.0) | 9.4 (5.1) | 8.2 (4.3) | 7.7 (4.4) | 8.9 (4.8) | 8.3 (4.4) | |

| Time since initiation of levodopa, y, ne | –d | –d | 255 | –d | –d | 584 | 452 | 591 |

| Mean (SD) | 8.1 (5.1) | 7.5 (4.8) | 7.2 (4.2) | 8.7 (4.4) | ||||

| Time since onset of motor complications, ne | 195 | 395 | 225 | 357 | 366 | 582 | 453 | 587 |

| Mean (SD) | 4.1 (3.5) | 4.5 (3.9) | 3.8 (3.5) | 3.3 (2.8) | 3.3 (3.1) | 3.6 (3.4) | 3.1 (2.8) | 6.0 (4.3) |

| Anti-Parkinson medication used at baseline and throughout studyf | ||||||||

| Concomitant anti-Parkinson medications, n (%) | 195 (100.0) | 395 (100.0) | 225 (100.0) | 357 (100.0) | 366 (100.0) | 584 (100.0) | 455 (100.0) | 592 (100.0) |

| DOPA and DOPA derivatives | 195 (100.0) | 395 (100.0) | 225 (100.0) | 357 (100.0) | 366 (100.0) | 584 (100.0) | 455 (100.0) | 592 (100.0) |

| DAs | 150 (76.9) | 301 (76.2) | 171 (76.0) | 330 (92.4) | 318 (86.9) | 430 (73.6) | 226 (49.7) | 463 (78.2) |

| COMT inhibitors | 80 (41.0) | 172 (43.5) | 101 (44.9) | 53 (14.8) | 183 (50.0) | 278 (47.6) | 0 g | 227 (38.3) |

| MAO-B inhibitors | 33 (16.9) | 63 (15.9) | 26 (11.6) | 186 (52.1) | 184 (50.3) | 76 (13.0) | 38 (8.4) | 220 (37.2) |

| Adamantane derivatives | 55 (28.2) | 110 (27.8) | 70 (31.1) | 127 (35.6) | 134 (36.6) | 151 (25.9) | 134 (29.5) | 194 (32.8) |

| Anticholinergics | 9 (4.6) | 18 (4.6) | 21 (9.3) | 64 (17.9) | 50 (13.7) | 24 (4.1) | 84 (18.5) | 27 (4.6) |

| Otherh | 3 (1.5) | 6 (1.5) | 0 | 89 (24.9) | 122 (33.3) | 27 (4.6) | 10 (2.2) | 10 (1.7) |

aITT population, total for all treatment groups in the study, including placebo; bObserved case; cUPDRS Part III score = sum of UPDRS questions 18 to 31 (motor examination); dNot collected; eCalculated relative to screening visit date; fPatients shown as receiving DA, COMT inhibitor, or MAO-B inhibitor may have also been receiving other categories of PD medications; gEntacapone was an active comparator in this study; therefore, concomitant COMT inhibitors were not allowed, per protocol; hPrimarily includes domperidone, droxidopa, promethazine, and zonisamide for Studies 6002-0608 and 6002-009; BMI, body mass index; COMT, catechol-O-methyltransferase; DA, dopamine agonist; ITT, intent-to-treat; MAO-B, monoamine oxidase B; PD, Parkinson’s disease; SD, standard deviation; UPDRS, Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale.

Patient disposition

Of patients randomized in the eight studies, 87.8%to 90.1%completed the 12- or 16-week treatment periods. The most frequent reason for premature discontinuation was AEs (placebo, 1.7%to 7.6%; 20 mg/day, 3.7%to 9.4%, and 40 mg/day, 4.8%to 10.6%), followed by withdrawn consent (placebo, 1.3%to 5.9%; 20 mg/day, 0 to 4.9%; 40 mg/day, 0 to 3.2%; Supplementary File 1, Supplementary Table 3).

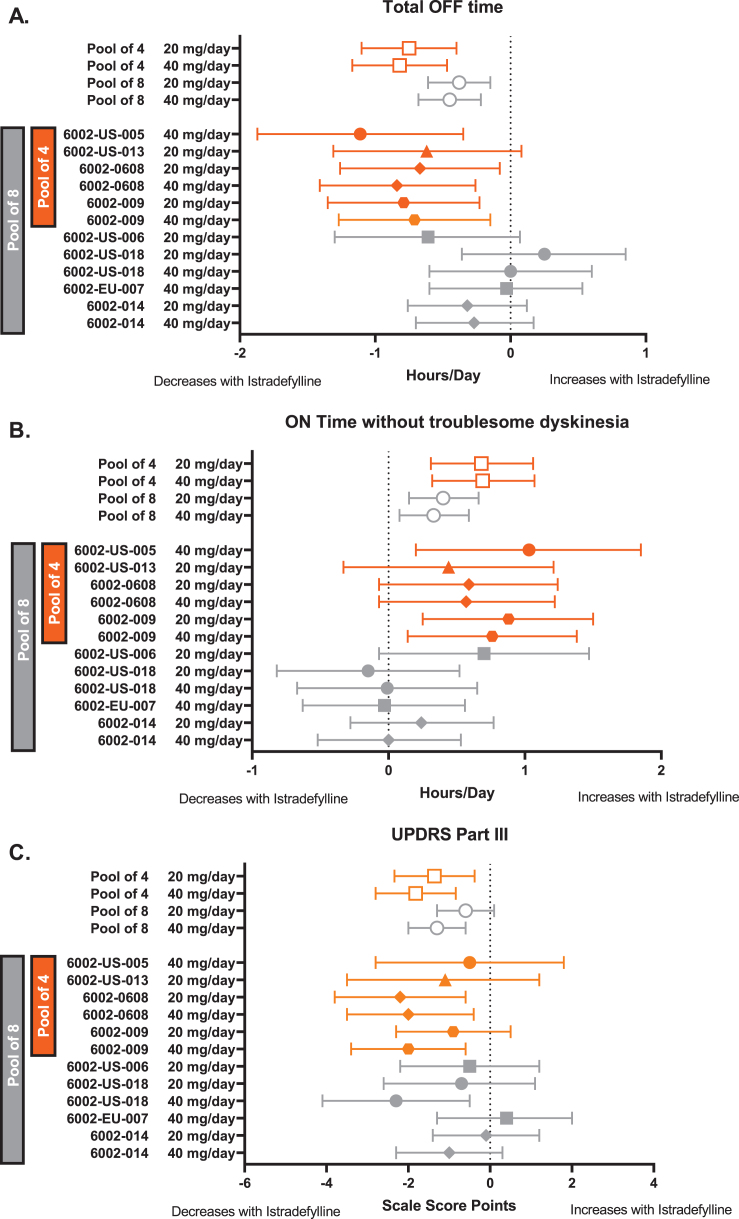

Efficacy outcomes: eight-study pool

In the pooled analysis of eight studies, istradefylline reduced mean OFF hours/day at Week 12 relative to placebo at 20 mg/day (LS mean difference from placebo [95%CI], –0.38 h [–0.61, –0.15], p = 0.0011) and 40 mg/day (–0.45 h [–0.68, –0.22], p < 0.0001; Fig. 1A). Total hours/day ON without troublesome dyskinesia significantly increased with istradefylline at 20 mg/day (0.40 h [0.15, 0.66], p = 0.0021) and 40 mg/day (0.33 h [0.08, 0.59], p = 0.0098) compared with placebo (Fig. 1B) The placebo-adjusted effect of istradefylline on the increase in ON time without troublesome dyskinesia was comparable to the decrease in OFF time, and there was no significant difference between istradefylline and placebo in total hours/day of ON time with troublesome dyskinesia in the 20 mg/day (0.08 h [–0.06, 0.21]) and 40 mg/day (0.13 h [0.00, 0.26]) groups (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Forest plot of 8 randomized trials (MMRM) showing LS mean difference from placebo in the change from baseline to Week 12 in (A) OFF hours/day, (B) hours/day ON without troublesome dyskinesia, and (C) UPDRS Part III ON. The symbol on each horizontal line is the LS mean difference from placebo in the change from baseline for the istradefylline dosage shown at left. The horizontal line is the 95%CI. The 4 studies in orange were included in the US label for istradefylline. For panels A and C, negative values indicate improvement; for panel B, positive values indicate improvement. Open symbols = pooled results; filled symbols = individual study results. CI, confidence interval; MMRM, mixed-model repeated measures; UPDRS Part III, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, Part III (motor function).

Table 2.

Efficacy endpoints for the 8- and 4-study pools

| Efficacy endpoint | LS mean difference from placebo in the change from baseline (95%CI) | |

| Istradefylline 20 mg/day | Istradefylline 40 mg/day | |

| Total OFF time (hours/day) | ||

| 8-study pool | –0.38 (–0.61, –0.15) | –0.45 (–0.68, –0.22) |

| 4-study pool | –0.75 (–1.10, –0.40) | –0.82 (–1.17, –0.47) |

| ON time without troublesome dyskinesia (hours/day) | ||

| 8-study pool | 0.40 (0.15, 0.66) | 0.33 (0.08, 0.59) |

| 4-study pool | 0.68 (0.31, 1.06) | 0.69 (0.32, 1.07) |

| Total ON time (hours/day) | ||

| 8-study pool | 0.48 (0.24, 0.71) | 0.45 (0.22, 0.69) |

| 4-study pool | 0.81 (0.46, 1.16) | 0.84 (0.49, 1.20) |

| ON time without dyskinesia (hours/day) | ||

| 8-study pool | 0.15 (–0.13, 0.44) | 0.07 (–0.22, 0.35) |

| 4-study pool | 0.50 (0.10, 0.90) | 0.53 (0.13, 0.94) |

| ON time with troublesome dyskinesia (hours/day) | ||

| 8-study pool | 0.08 (–0.06, 0.21) | 0.13 (0.00, 0.26) |

| 4-study pool | 0.13 (–0.07, 0.32) | 0.15 (–0.05, 0.34) |

| UPDRS Part II ON (score) | ||

| 8-study pool | 0.1 (–0.2, 0.4) | –0.2 (–0.5, 0.1) |

| 4-study pool | 0.19 (–0.19, 0.56) | –0.24 (–0.61, 0.14) |

| UPDRS Part III ON (score) | ||

| 8-study pool | –0.6 (–1.3, 0.1) | –1.3 (–2.0, –0.6) |

| 4-study pool | –1.36 (–2.34, –0.38) | –1.82 (–2.80, –0.84) |

CI, confidence interval; LS, least-squares; UPDRS, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale.

There was a consistent trend toward improvement in UPDRS Part III (ON) scores with istradefylline at both 20 mg/day (–0.6 points [–1.3, 0.1]) and 40 mg/day (–1.3 points [–2.0, –0.6]) relative to placebo (Fig. 1C). Pooled results for all diary endpoints and for UPDRS Parts II and III scores are shown in Table 2.

Safety outcomes

In the pooled safety analysis of all eight studies, the average completion rate was 89.2%across all istradefylline doses and 89.8%for the pooled placebo group. The incidence of TEAEs was generally similar across the three groups (placebo, 65%; 20 mg/day, 71%; 40 mg/day, 70%), and the most frequent AE was dyskinesia (9.6%, 16.1%, and 17.7%, respectively; Table 3), which was mostly mild or moderate in severity and led to discontinuation from study for 0.7%, 0.8%, and 1.5%of patients in the placebo, 20 mg/day and 40 mg/day groups. Dyskinesia was more frequently reported as an AE in istradefylline- and placebo-treated patients with pre-existing dyskinesia noted in baseline diaries (placebo, 14.1%; 20 mg/day, 24.7%; 40 mg/day, 25.9%) compared with patients without pre-existing dyskinesia (placebo, 3.5%; 20 mg/day, 4.4%; 40 mg/day, 8.4%).

Table 3.

Frequency of TEAEs occurring in ≥5%of patients receiving istradefylline 20 or 40 mg/day in the safety population

| Adverse event, n (%) | Placebo | Istradefylline | |

| 20 mg/day | 40 mg/day | ||

| 8-study pool, n | 1010 | 869 | 896 |

| Any TEAE | 661 (65.4) | 614 (70.7) | 628 (70.1) |

| Dyskinesia | 97 (9.6) | 140 (16.1) | 159 (17.7) |

| Nausea | 46 (4.6) | 52 (6.0) | 54 (6.0) |

| Fall | 50 (5.0) | 35 (4.0) | 45 (5.0) |

| Dizziness | 42 (4.2) | 44 (5.1) | 44 (4.9) |

| Constipation | 33 (3.3) | 50 (5.8) | 48 (5.4) |

| Insomnia | 42 (4.2) | 31 (3.6) | 48 (5.4) |

| 4-study pool, n | 426 | 356 | 378 |

| Any TEAE | 278 (65.3) | 241 (67.7) | 263 (69.6) |

| Dyskinesia | 32 (7.5) | 52 (14.6) | 63 (16.7) |

| Nausea | 20 (4.7) | 15 (4.2) | 24 (6.3) |

| Dizziness | 16 (3.8) | 11 (3.1) | 21 (5.6) |

| Constipation | 12 (2.8) | 19 (5.3) | 21 (5.6) |

| Insomnia | 15 (3.5) | 2 (0.6) | 21 (5.6) |

| Viral upper respiratory tract infection | 20 (4.7) | 22 (6.2) | 20 (5.3) |

TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

In istradefylline-treated patients, there was little or no increase in the incidence of AEs commonly observed in patients with PD during treatment with levodopa and other dopaminergic anti-Parkinson medications (nausea and vomiting, hallucinations, impulse control disorders, orthostatic hypotension, somnolence/sleepiness) ( Supplementary File 1, Supplementary Table 4). No clinically meaningful changes in laboratory parameters, vital signs, or ECG parameters were observed.

Efficacy and safety outcomes: four-study pool

In the pooled analysis of four studies, the LS mean difference from placebo in the change from baseline in total OFF hours/day at Week 12 was –0.75 h (95%CI, –1.10, –0.40) for istradefylline 20 mg/day and –0.82 h (–1.17, –0.47) for 40 mg/day (Fig. 1A). The change from baseline in total hours/day ON without troublesome dyskinesia at Week 12 increased with both the 20 mg/day (LS mean difference from placebo [95%CI], 0.68 h [0.31, 1.06]) and 40 mg/day (0.69 h [0.32, 1.07]) dosages of istradefylline compared with placebo (Fig. 1B). The placebo-adjusted effect of istradefylline on the increase from baseline in ON time without troublesome dyskinesia was comparable to the decrease in daily OFF time.

At Week 12, UPDRS Part III (ON) scores in the 4-study pool demonstrated a significant improvement at both 20 mg/day (–1.36 points [–2.34, –0.38]; p = 0.006) and 40 mg/day (–1.82 points [–2.80, –0.84]; p < 0.001) istradefylline relative to placebo (Fig. 1C).

In the pooled analysis of 4 studies, the most frequent AEs were dyskinesia (placebo, 7.5%; 20 mg/day, 14.6%; 40 mg/day, 16.7%), nausea (4.7%, 4.2%, 6.3%), and dizziness (3.8%, 3.1%, 5.6%; Table 3). Dyskinesia led to study discontinuation in no placebo-treated patients, 1.1%of patients treated at 20 mg/day, and 1.3%treated at 40 mg/day. Rates of AEs of special interest in the 4-study pool are shown in Supplementary File 1, Supplementary Table 4.

DISCUSSION

In this pooled analysis from 8 clinical trials of patients with PD receiving levodopa and other concomitant anti-Parkinson medications, istradefylline 20 and 40 mg/day significantly decreased OFF time and increased ON time without troublesome dyskinesia relative to placebo. UPDRS Part III (ON) also demonstrated a trend toward improvement. We believe the value of this report derives from the fact that 1) the 8-study pool reflects the full clinical development experience of istradefylline when evaluated as adjunctive treatment for patients with OFF time in phase 2b/3 double-blind clinical trials, including two previously unpublished studies, and 2) we provide a pooled analysis of the four studies that were selected by the US FDA in order to enable readers to better interpret and understand the data that underlies istradefylline’s US product label. Importantly, these analyses demonstrated consistent effects of istradefylline. All randomized patients received levodopa, and 95%were receiving additional anti-Parkinson medication. Therefore, all results were obtained in addition to a background of levodopa/decarboxylase inhibitor with or without other anti-Parkinson medications.

In the 8-study pooled analysis, the magnitude of the reduction in OFF time (20 mg/day, –0.38 h; 40 mg/day, –0.45 h) was similar to the increase in ON without troublesome dyskinesia (20 mg/day, 0.40 h; 40 mg/day, 0.33 h). The directionality and size of the effect of treatment were mostly consistent among the studies (Fig. 1). These findings indicate that istradefylline causes reciprocal changes in OFF time and ON time without troublesome dyskinesia, suggesting that the reduced OFF time is transformed to ON without troublesome dyskinesia. Dyskinesia was observed as an AE in 16.1%(20 mg) and 17.7%(40 mg) of istradefylline-treated patients compared with 9.6%of placebo-treated patients in the 8-study pool. As reported in a post-marketing surveillance study of 476 patients with PD receiving istradefylline, patients with pre-existing dyskinesia had a higher frequency of dyskinesia relative to those without baseline dyskinesia (10.6%vs 1.7%, respectively) [23]. These findings are consistent with the present report, which demonstrated that dyskinesia as an AE was reported more frequently among patients with dyskinesia at baseline. Although the majority of patients did not report dyskinesia, it is possible that dyskinesia arose in part because the increased amount of ON time observed in istradefylline-treated patients increased the time during which this AE could occur.

These efficacy findings are consistent with a recent pooled analysis of two of the studies included in this analysis that were conducted in Japan—this analysis found that istradefylline was associated with reduced OFF time and increased ON time without troublesome dyskinesia [24]. Additionally, a previous meta-analysis of 6 of the 8 trials presented here found that, relative to placebo, OFF time and motor symptoms improved with istradefylline, whereas dyskinesia occurred more frequently [20]; these findings are consistent with the present analysis, which encompasses a larger and more diverse patient population and includes two previously unpublished studies that did not demonstrate statistically significant differences in endpoints. In the present analysis, if dyskinesia became problematic, the levodopa dose could be reduced. However, in a proof-of-concept study, istradefylline added to a low-dose IV levodopa infusion potentiated the antiparkinsonian response and caused less dyskinesia compared with that induced by an optimal-dose IV levodopa infusion alone [25]. This strategy of lowering the levodopa dose and adding istradefylline has not yet been tested in patients with PD and dyskinesia on oral levodopa but remains of interest for future trials.

For new drug applications, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration requires “substantial evidence” of drug safety and efficacy and interprets this as needing at least two adequate and well-controlled phase 3 trials with convincing evidence of effectiveness [26]. For the US approval of istradefylline, four clinical trials were included in the label to support its safety and efficacy. In these trials, istradefylline doses of 20 mg/day (6002-US-013, –0.62 h; 6002-0608, –0.67 h; 6002-009, –0.67 h) and 40 mg/day (6002-US-005, –1.11 h; 6002-0608, –0.84; 6002-0609, –0.71 h) significantly reduced OFF time compared with placebo. The magnitude of the OFF time reduction in the 4-study pool was somewhat greater than the reduction observed in the more comprehensive 8-study pool, which would be expected given that these 4 trials were selected based on their positive results in the primary analysis. ON time without troublesome dyskinesia and UPDRS scores also showed a somewhat larger magnitude of change in the 4-study pool.

Experience with adenosine A2A antagonists suggests variability in outcome across trials, probably owing to issues of study conduct. In a phase 2 trial of preladenant, 5 mg BID reduced OFF time compared with placebo by 1.0 h (p = 0.0486) and 10 mg BID by 1.2 h (p = 0.019) [27]. However, in two phase 3 trials, preladenant failed to significantly reduce OFF time compared with placebo. Notably, rasagiline was included as an active control in one of the phase 3 studies, and it also failed to significantly reduce OFF time compared with placebo [28]. Although methodologic issues that could have accounted for these results were identified, further development of preladenant was discontinued.

In clinical trials of the adenosine A2A receptor antagonist tozadenant, reduction in daily OFF time relative to placebo was variable, ranging from –1.2 h in the initial phase 2b study to –0.83 in the phase 3 trial, the latter of which is comparable to the present findings [29, 30]. However, clinical development of tozadenant was prematurely terminated due to agranulocytosis and 7 cases of sepsis, with 5 of 7 ending in death [31]. The present analysis found that rates of neutropenia, including agranulocytosis, in istradefylline-treated patients were low in both the 8- (20 mg/day, 0.5%; 40 mg/day, 0.8%) and 4-study (20 mg/day, 0.3%; 40 mg/day, 0.5%) pools ( Supplementary File 1, Supplementary Table 4).

The magnitude of reduction in OFF time with istradefylline (20 or 40 mg/day) in the current pooled analysis is generally in the range reported in a Cochrane review of efficacy and safety of adjunctive treatments to levodopa therapy in PD patients with motor complications [2]. Safinamide 50 mg and 100 mg reduced daily OFF time in two studies, with an LS mean difference from placebo of –0.5 to –1.0 h [32]. Opicapone 50 mg reduced daily OFF time by –0.9 h (LS mean difference from placebo) in 2 registration studies [33]. In the 4-study pool reported here, istradefylline 20 mg/day and 40 mg/day reduced daily OFF time, with an LS mean difference from placebo ranging from –0.6 to –1.1 h.

The purpose of our analyses was to provide a transparent overview of the eight phase 2b/3, placebo-controlled studies of istradefylline as an adjunct to levodopa, including two that were previously unpublished, as well as the subset of four trials that were used by the FDA as the basis for istradefylline’s approval. A strength of our analysis is the large patient population evaluated and the inclusion of multiple, similarly designed studies, which facilitated pooling. Another strength of this analysis is that patients could be on multiple anti-PD medications, which enabled the study population to reflect treatment patterns likely observed in real-world clinical practice. A potential weakness of our analysis is that minor differences in study design, such as location, number of diary entries, and the guidance around adjusting dopaminergic therapies during treatment, led to some heterogeneity between trials that could have affected results of individual studies and complicated interpretation of this pooled analysis. Additionally, pooling of data can inherently lead to over-powering, where positive outcomes (efficacy endpoints) may appear stronger than in the original, individual studies.

This post hoc, pooled analysis demonstrated that istradefylline (20 and 40 mg/day) significantly improved OFF time and ON time without troublesome dyskinesia in patients with PD treated with levodopa and other concomitant anti-Parkinson medications. Motor function (UPDRS Part III ON) also showed a trend toward improvement. These improvements in PD symptoms occurred when istradefylline was administered in addition to a variety of other anti-Parkinson medications, yet there was little to no increase in AEs typically associated with dopaminergic therapies. As many patients with PD continue experiencing motor fluctuations despite available dopaminergic therapies, additional options are needed to provide symptom relief. The findings of this analysis indicate that targeting the adenosine A2A receptor in the indirect pathway of the basal ganglia facilitates an improvement in OFF time and PD symptoms in patients on dopamine-targeting therapies. This inclusive analysis of eight randomized, placebo-controlled trials affords clinicians an overview of istradefylline’s efficacy, safety, and tolerability. Istradefylline was generally well-tolerated and provided a clinical benefit in patients with PD who continued to experience motor fluctuations.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors and investigators would like to thank the patients and caregivers who participated in these studies. They would also like to thank Phyllis Salzman, PhD (Kyowa Kirin Pharmaceutical Development) and Keizo Toyama (Kyowa Kirin Co., Ltd.,) for their contributions to the summarization of results. Meghan Sullivan, PhD, and Anthony DiLauro, PhD, of MedVal Scientific Information Services, LLC, provided medical writing and editorial assistance, which were funded by Kyowa Kirin, Inc. This manuscript was prepared according to the International Society for Medical Publication Professionals’ “Good Publication Practice for Communicating Company-Sponsored Medical Research: GPP3.”

Development of this manuscript was funded by Kyowa Kirin, Inc. Kyowa Kirin Pharmaceutical Development, Inc., consulted with advisors and study investigators on the design of these studies, provided financial and material support for these studies, and, with the assistance of study investigators, monitored the conduct of these studies, collected data from the investigative centers, and analyzed the data.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JPD-212672.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

RAH: The USF Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders Center receives financial support from the Parkinson Foundation as a Center of Excellence. Research Funding/Investigator: AbbVie, Axovant, Biogen, Bukwang, Cavion, Centogene, Cerevance, Cerevel, Cynapsus, Enterin, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Genentech, Global Kinetics Corporation, Impax, Intec Pharma, Integrative Research Laboratories, Jazz, Michael J Fox Foundation, Neuraly, Neurocrine, NeuroDerm, Northwestern University, Parkinson’s Foundation, Pfizer, Pharma Two B, Revance, and Sanofi; Advisor/Consultant: AbbVie, Academy for Continued Healthcare Learning, Acadia, Acorda, Adamas, Affiris, Alliance for Aging Research, AlphaSights, Amneal, ApoPharma, Aptis Partners, Aranca, Axial Biotherapeutics, Axovant Sciences, Bain Capital, Baron, Britannia, Cadent, Capital, CereSpir, Clearview Healthcare Partners, CNS Ratings, Compass Group, Decision Resources Group (DRG), Defined Health, Deallus Consulting, Denali, DOB Health, Enterin, Evercore, Extera Partners, GE Healthcare, Gerson Lehrman Group (GLG), Global Kinetics, Guidepoint Global, Health and Wellness Partners, HealthLogiX, Heptares, Huron Consulting Group, Impax Laboratories, Impel NeuroPharma, Inhibikase, Intec Pharma, International Stem Cell, IntraMed Educational Group, IQVIA, Jazz, Kaiser, Kashiv, Kyowa Kirin Pharmaceutical Development, L.E.K. Consulting, Lundbeck, Lundbeck A/S, MEDACorp, MEDIQ, Medscape, Medtronic, Michael J. Fox Foundation, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Movement Disorder Society, Neuro Challenge Foundation for Parkinson’s, Neurocea, Neurocrine Biosciences, NeuroDerm, Northwestern University, Orbes, Orbes Medical Group, Orion, Parkinson Study Group, Parkinson’s Foundation, Partners Healthcare, Penn Technology Partnership, Pennside Partners, Perception OpCo, Precision Effect, Phase Five Communications, Prescott Medical Group, Prilenia, Projects in Knowledge, Regenera, SAI MedPartners, Schlesinger Associates, Scion NeuroStim, Seagrove Partners, Seelos, Slingshot Insights, Sun Pharma, Sunovion, Teva, The Lockwood Group, US WorldMeds, WebMD, and Windrose Consulting Group; Honoraria: AbbVie, Academy for Continued Healthcare Learning, Acadia, Acorda, Adamas, Affiris, Alliance for Aging Research, AlphaSights, Amneal, ApoPharma, Aptis Partners, Aranca, Axial Biotherapeutics, Axovant Sciences, Bain Capital, Baron, Britannia, Cadent, Capital, CereSpir, Clearview Healthcare Partners, CNS Ratings, Compass Group, Decision Resources Group (DRG), Defined Health, Deallus Consulting, Denali, DOB Health LLC, Enterin, Evercore, Extera Partners, GE Healthcare, Gerson Lehrman Group (GLG), Global Kinetics, Guidepoint Global, Health and Wellness Partners, HealthLogiX, Heptares, Huron Consulting Group, Impax Laboratories, Impel NeuroPharma, Inhibikase, Intec Pharma, International Stem Cell, IntraMed Educational Group, IQVIA, Jazz, Kaiser, Kashiv, Kyowa Kirin Pharmaceutical Development, L.E.K. Consulting, Lundbeck, Lundbeck A/S, MEDACorp, MEDIQ, Medscape, Medtronic, Michael J. Fox Foundation, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Movement Disorder Society, Neuro Challenge Foundation for Parkinson’s, Neurocea, Neurocrine Biosciences, NeuroDerm, Northwestern University, Orbes, Orbes Medical Group, Orion, Parkinson Study Group, Parkinson’s Foundation, Partners Healthcare, Penn Technology Partnership, Pennside Partners, Perception OpCo, Precision Effect, Phase Five Communications, Prescott Medical Group, Prilenia, Projects in Knowledge, Regenera, SAI MedPartners, Schlesinger Associates, Scion NeuroStim, Seagrove Partners, Seelos, Slingshot Insights, Sun Pharma, Sunovion, Teva, The Lockwood Group, US WorldMeds, WebMD, and Windrose Consulting Group; Speakers Bureau: Acorda, Adamas, Amneal, Kyowa Kirin Pharmaceutical Development, Neurocrine Biosciences and US WorldMeds; Equity Ownership, Axial Biotherapeutics and Inhibikase.

NH: Research Funding/Investigator: AbbVie GK, Asahi Kasei, Astellas, Boston Scientific, Dai-Nippon Sumitomo, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, FP Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Medtronic, Mitsubishi Tanabe, MiZ, Nihon Medi-physics, Nihon Pharmaceutical, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, OHARA, Ono Pharmaceutical, Otsuka, and Takeda; Subcontracting (Trial Cases): Biogen Japan, Hisamitsu, and Meiji Seika; Contract Research: Biogen Japan and Mitsubishi Tanabe; Advisor/Consultant: Dai-Nippon Sumitomo; Advisory Boards: Dai-Nippon Sumitomo, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Otsuka, Sanofi KK, and Takeda; Honoraria: AbbVie GK, Alexion, Boston Scientific, Dai-Nippon Sumitomo, Daiichi Sankyo, FP Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Lundbeck Japan, Medtronic, MSD KK, Mylan, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, and Takeda.

HF: Research Funding/Investigator: Acorda, Alkahest, Amneal, Biogen, Michael J. Fox Foundation, Movement Disorders Society, NIH/NINDS, Parkinson Study Group, and Sunovion; Honoraria: Bial Neurology, Biopas, Boston University, Cerevel, Cleveland Clinic, CNS Ratings, Covance, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, New York University, Parkinson Study Group, Partners Healthcare System, Revance, Sun Pharma, and Sunovion Research and Development Trust; Royalties From Book Authorship/Editorial Work: Demos Publishing and Springer Publishing. Dr. Fernandez receives compensation from Elsevier as Editor-in-Chief of Parkinsonism and Related Disorders. Dr. Fernandez is contracted by Teva as a co-principal investigator in global studies of deutetrabenazine for tardive dyskinesia.

SHI: Research Funding/Investigator: AbbVie, Acadia, Acorda, Adamas, Axovant, Biogen, Eli Lilly, Enterin, GE Healthcare, Global Kinetics, Impax Laboratories, Intec Pharma, Kyowa, Lundbeck, Michael J. Fox Foundation, NeuroDerm, Parkinson Study Group, Pharma Two B, Roche, Sanofi, Sunovion, UCB, and US WorldMeds; Advisor/Consultant: AbbVie, Acadia, Acorda, Adamas, Allergan, Britannia, Enterin, GE Healthcare, Global Kinetics, Impax Laboratories, Kyowa, Lundbeck, Neurocrine, NeuroDerm, Roche, Sunovion, Teva, and US WorldMeds; Advisory Boards: Acadia, Acorda, Adamas, Lundbeck, NeuroDerm, Parkinson Study Group, Pharma Two B, Roche, Sanofi, Sunovion, Teva, UCB, and US WorldMeds; Speakers Bureau: AbbVie, Acadia, Acorda, Adamas, Allergan, GE Healthcare, Impax Laboratories, Lundbeck, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Teva, UCB, and US WorldMeds.

HM: Research Funding/Investigator: Astellas, Bayer Yakuhin, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Dai-Nippon Sumitomo, Kyowa Kirin, Janssen, Shionogi, and Teijin; Advisory Boards: Biogen, Eisai, FP Pharmaceutical, Kissei, Kyowa Kirin, Ono Pharmaceutical, and Takeda; Honoraria: AbbVie, Alnylam Japan, Dai-Nippon Sumitomo, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, FP Pharmaceutical, Insightec, Kyowa Kirin, Novartis, SRL, and Takeda.

OR: Research Funding/Investigator: Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR), CHU de Toulouse, European Commission (FP7, H2020), France-Parkinson, INSERM-DHOS Recherche Clinique Translationnelle, Michael J. Fox Foundation, Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique; Advisor/Consultant: AbbVie, Adamas, Acorda, Addex, Alzprotect, ApoPharma, AstraZeneca, Bial, Biogen, Britannia, Bukwang, Cerevel, Clevexel, IRLAB, Lilly, Lundbeck, Lupin, Merck, Mundipharma, NeurATRIS, Neuroderm, Novartis, ONO Pharma, Orion, Osmotica, Oxford Biomedica, Parexel, Pfizer, Prexton, Quintiles, Sanofi, Servier, Sunovion, Theranexus, Takeda, Teva, UCB, Watermark Research, XenoPort, XO, Zambon.

FS: Advisory Boards: BIAL, Biogen, Britannia, Chiesi Farmaceutici, Cynapsus, Impax Laboratories, Kyowa Kirin Pharmaceutical Development, Lundbeck A/S, NeuroDerm, Sunovion, UCB, and Zambon.

JL, AM, YN, RR: Employment, Kyowa Kirin.

PL: Advisor/Consultant: Abide, Acadia, Acorda, Biogen, Britannia, Bukwang, Cynapsus, Impax, Insightec, Intec Pharma, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Lundbeck, Luye, Neurocrine, NeuroDerm, Pfizer, ProStrakan, Roche, Sage, SynAgile, Teva, UCB, and US WorldMeds; Honoraria: Acadia, International Parkinson’s and Movement Disorders Society, Lundbeck, and US WorldMeds. Dr. LeWitt receives compensation from Elsevier as Editor-in-Chief of Clinical Neuropharmacology and is not compensated for participation on the editorial boards of Journal of Neural Neurodegeneration, and Journal of Parkinson’s Disease. He reports institutional research support (The Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders Program) from Acorda, Adamas, Biotie, Michael J. Fox Foundation, Neurocrine, Parkinson Study Group, Pharma Two B, Roche, and US WorldMeds

PRIOR PRESENTATIONS

Results reported here were presented as posters at the Parkinson Study Group Annual meeting (April 5–8th, 2019, Chandler, AZ), the 13th World Congress on Controversies in Neurology (April 4–7th, 2019, Madrid, Spain), the American Academy of Neurology Annual Meeting (May 4–10th, 2019, Philadelphia, PA), the World Parkinson’s Congress (June 4–7, 2019, Kyoto, Japan), and the International Association of Parkinsonism and Related Disorders Annual Meeting (June 16–19, 2019, Montreal, Canada).

REFERENCES

- [1]. Jankovic J (2005) Motor fluctuations and dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease: Clinical manifestations. Mov Disord 20, 11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Stowe R, Ives N, Clarke CE, Handley K, Furmston A, Deane K, van Hilten JJ, Wheatley K, Gray R (2011) Meta-analysis of the comparative efficacy and safety of adjuvant treatment to levodopa in later Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 26, 587–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Chou KL (2008) Adverse events from the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Neurol Clin 26, S65–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Nourianz™ (istradefylline) tablets, for oral use (prescribing information). Kyowa Kirin Inc. Bedminster, NJ. 2019. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/022075s000lbl.pdf. Accessed 27 August 2019. Accessed 27 Aug 2019.

- [5]. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (2013). Report on the deliberation results. Available at: https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000153870.pdf. Accessed 14 Feb 2019.

- [6]. Mori A, LeWitt P, Jenner P (2015) The story of istradefylline—the first approved A2A antagonist for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. In The Adenosinergic System: A Non-Dopaminergic Target in Parkinson’s Disease, Morelli M, Simola N,Wardas J, eds. Springer International Publishing, Basel, Switzerland, pp. 273–289. [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Saki M, Yamada K, Koshimura E, Sasaki K, Kanda T (2013) In vitro pharmacological profile of the A2A receptor antagonist istradefylline. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 386, 963–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Svenningsson P, Le Moine C, Aubert I, Burbaud P, Fredholm BB, Bloch B (1998) Cellular distribution of adenosine A2A receptor mRNA in the primate striatum. J Comp Neurol 399, 229–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Mishina M, Ishiwata K, Kimura Y, Naganawa M, Oda K, Kobayashi S, Katayama Y, Ishii K (2007) Evaluation of distribution of adenosine A2A receptors in normal human brain measured with [11C]TMSX PET. Synapse 61, 778–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Mori A (2014) Mode of action of adenosine A2A receptor antagonists as symptomatic treatment for Parkinson’s disease. Int Rev Neurobiol 119, 87–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Svenningsson P, Hall H, Sedvall G, Fredholm BB (1997) Distribution of adenosine receptors in the postmortem human brain: An extended autoradiographic study. Synapse 27, 322–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Mishina M, Ishiwata K, Naganawa M, Kimura Y, Kitamura S, Suzuki M, Hashimoto M, Ishibashi K, Oda K, Sakata M, Hamamoto M, Kobayashi S, Katayama Y, Ishii K (2011) Adenosine A2A receptors measured with [11C]TMSX PET in the striata of Parkinson’s disease patients. PLoS One 6, e17338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Stacy M, Silver D, Mendis T, Sutton J, Mori A, Chaikin P, Sussman NM (2008) A 12-week, placebo-controlled study (6002-US-006) of istradefylline in Parkinson disease. Neurology 70, 2233–2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Pourcher E, Fernandez HH, Stacy M, Mori A, Ballerini R, Chaikin P (2012) Istradefylline for Parkinson’s disease patients experiencing motor fluctuations: Results of the KW-6002-US-018 study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 18, 178–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Hauser RA, Shulman LM, Trugman JM, Roberts JW, Mori A, Ballerini R, Sussman NM, Istradefylline 6002-US-013 Study Group (2008) Study of istradefylline in patients with Parkinson’s disease on levodopa with motor fluctuations. Mov Disord 23, 2177–2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. LeWitt PA, Guttman M, Tetrud JW, Tuite PJ, Mori A, Chaikin P, Sussman NM, 6002-US-005 Study Group (2008) Adenosine A2A receptor antagonist istradefylline (KW-6002) reduces “off” time in Parkinson’s disease: A double-blind, randomized, multicenter clinical trial (6002-US-005). Ann Neurol 63, 295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Mizuno Y, Hasegawa K, Kondo T, Kuno S, Yamamoto M, Japanese Istradefylline Study Group (2010) Clinical efficacy of istradefylline (KW-6002) in Parkinson’s disease: A randomized, controlled study. Mov Disord 25, 1437–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Mizuno Y, Kondo T, Japanese Istradefylline Study Group (2013) Adenosine A2A receptor antagonist istradefylline reduces daily OFF time in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 28, 1138–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Isaacson S, Eggert K, Kumar R, Stocchi F, Mori A, Ohta E, Toyama K, Spence G, Clark G, Cantillon M (2017) Efficacy and safety of istradefylline in moderate to severe Parkinson’s disease: A phase 3, multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (i-step study) [abstract]. J Neurol Sci 381, 351–352. [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Sako W, Murakami N, Motohama K, Izumi Y, Kaji R (2017) The effect of istradefylline for Parkinson’s disease: A meta-analysis. Sci Rep 7, 18018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Chen W, Wang H, Wei H, Gu S, Wei H (2013) Istradefylline, an adenosine A2A receptor antagonist, for patients with Parkinson’s disease: A meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci 324, 21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Hauser RA, Friedlander J, Zesiewicz TA, Adler CH, Seeberger LC, O’Brien CF, Molho ES, Factor SA (2000) A home diary to assess functional status in patients with Parkinson’s disease with motor fluctuations and dyskinesia. Clin Neuropharmacol 23, 75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Takahashi M, Fujita M, Asai N, Saki M, Mori A (2018) Safety and effectiveness of istradefylline in patients with Parkinson’s disease: Interim analysis of a post-marketing surveillance study in Japan. Expert Opin Pharmacother 19, 1635–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Hattori N, Kitabayashi H, Kanda T, Nomura T, Toyama K, Mori A (2020) A pooled analysis from phase 2b and 3 studies in Japan of istradefylline in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 35, 1481–1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Bara-Jimenez W, Sherzai A, Dimitrova T, Favit A, Bibbiani F, Gillespie M, Morris MJ, Mouradian MM, Chase TN (2003) Adenosine A(2A) receptor antagonist treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 61, 293–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Van Norman GA (2016) Drugs, devices, and the FDA: Part 1: An overview of approval processes for drugs. JACC Basic Transl Sci 1, 170–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Hauser RA, Cantillon M, Pourcher E, Micheli F, Mok V, Onofrj M, Huyck S, Wolski K (2011) Preladenant in patients with Parkinson’s disease and motor fluctuations: A phase 2, double-blind, randomised trial. Lancet Neurol 10, 221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Hauser RA, Stocchi F, Rascol O, Huyck SB, Capece R, Ho TW, Sklar P, Lines C, Michelson D, Hewitt D (2015) Preladenant as an adjunctive therapy with levodopa in Parkinson disease: Two randomized clinical trials and lessons learned. JAMA Neurol 72, 1491–1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. Hauser RA, Olanow CW, Kieburtz KD, Pourcher E, Docu-Axelerad A, Lew M, Kozyolkin O, Neale A, Resburg C, Meya U, Kenney C, Bandak S (2014) Tozadenant (SYN115) in patients with Parkinson’s disease who have motor fluctuations on levodopa: A phase 2b, double-blind, randomised trial. Lancet Neurol 13, 767–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30]. Biotie Therapies Inc. (2019) Safety and efficacy study of tozadenant to treat end of dose wearing off in Parkinson’s patients (TOZ-PD). Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT02453386. Accessed 19 Mar 2020.

- [31]. Terry M (2017) Acorda takes a $363M hit as deaths lead to termination of Parkinson’s drug. Available at:. Accessed 9 Jul, 2020–https://www.biospace.com/article/unique-acorda-takes-a-363m-hit-as-deaths-lead-to-termination-of-parkinson-s-drug/.

- [32]. Xadago 50mg film-coated tablets (summary of product characteristics). Profile Pharma Limited. Chichester, England. 2019. Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/2159/. Accessed 11 May 2020.

- [33]. Ongentys 25mg hard capsules (summary of product characteristics). Bial - Portela & Ca. Trofa, Portugal. 2016. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/ongentys-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 13 Jan 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.