Abstract

We find that prothymosin alpha (PTα) selectively enhances transcriptional activation by the estrogen receptor (ER) but not transcriptional activity of other nuclear hormone receptors. This selectivity for ER is explained by PTα interaction not with ER, but with a 37-kDa protein denoted REA, for repressor of estrogen receptor activity, a protein that we have previously shown binds to ER, blocking coactivator binding to ER. We isolated PTα, known to be a chromatin-remodeling protein associated with cell proliferation, using REA as bait in a yeast two-hybrid screen with a cDNA library from MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. PTα increases the magnitude of ERα transcriptional activity three- to fourfold. It shows lesser enhancement of ERβ transcriptional activity and has no influence on the transcriptional activity of other nuclear hormone receptors (progesterone receptor, glucocorticoid receptor, thyroid hormone receptor, or retinoic acid receptor) or on the basal activity of ERs. In contrast, the steroid receptor coactivator SRC-1 increases transcriptional activity of all of these receptors. Cotransfection of PTα or SRC-1 with increasing amounts of REA, as well as competitive glutathione S-transferase pulldown and mammalian two-hybrid studies, show that REA competes with PTα (or SRC-1) for regulation of ER transcriptional activity and suppresses the ER stimulation by PTα or SRC-1, indicating that REA can function as an anticoactivator in cells. Our data support a model in which PTα, which does not interact with ER, selectively enhances the transcriptional activity of the ER but not that of other nuclear receptors by recruiting the repressive REA protein away from ER, thereby allowing effective coactivation of ER with SRC-1 or other coregulators. The ability of PTα to directly interact in vitro and in vivo with REA, a selective coregulator of the ER, thereby enabling the interaction of ER with coactivators, appears to explain its ability to selectively enhance ER transcriptional activity. These findings highlight a new role for PTα as a coregulator activity-modulating protein that confers receptor specificity. Proteins such as PTα represent an additional regulatory component that defines a novel paradigm enabling receptor-selective enhancement of transcriptional activity by coactivators.

Nuclear hormone receptors encompass the steroid/thyroid/retinoid receptor superfamily and are ligand-inducible transcription factors. These receptors modulate the transcription of specific genes by interacting with hormone response elements located near the target gene promoter (17, 21, 35). The estrogen receptor (ER), a member of the steroid receptor family, mediates the stimulatory effects of estrogens and the inhibitory effects of antiestrogens in breast cancer and other estrogen target cells. ER-regulated genes are involved in many biological processes, including cell growth and differentiation, morphogenesis, and programmed cell death (15, 16). The gene transcriptional activity by nuclear hormone receptors is enhanced or repressed by their interaction with regulatory factors which function positively (coactivator) or negatively (corepressor) as intermediates between the receptor and the RNA polymerase II transcription complex (2, 25, 33, 44). Recently, coregulators have been shown to have different modes of action in mediating their transcriptional effects. These proteins exist as a part of large, multicomponent complexes that can be recruited by nuclear hormone receptors and function, in part, as chromatin-remodeling factors (2, 29, 44).

We recently reported on an ER-selective coregulator, denoted REA for repressor of estrogen receptor activity, that interacts only with ER among the nuclear hormone receptors and represses the activity of the estrogen-occupied ER and potentiates the inhibitory activity of antiestrogens (27). To understand better the mechanism by which REA works, we used REA as a bait in a yeast two-hybrid screen with a cDNA library from MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. In this way, as we show in this paper, we identified the nuclear protein prothymosin alpha (PTα) as the 12.5-kDa protein with which REA interacts. This protein is widely distributed in human tissues and is known to be a chromatin-remodeling protein associated with cell proliferation (1, 6, 10, 14, 22, 38, 43). Intriguingly, we find that PTα selectively enhances the transcriptional activity of the ER but not that of other nuclear hormone receptors. We present data supporting a model to explain the receptor-selective transcription-enhancing ability of PTα, in which PTα recruits the repressive protein REA away from ER, thereby allowing coactivator binding and enhanced transcriptional activity by the ER.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and materials.

Cell culture media were purchased from Gibco (Grand Island, N.Y.). Calf serum was from Hyclone Laboratories (Logan, Utah), and fetal calf serum was from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, Mo.). Custom oligonucleotides were purchased from Gibco.

Plasmids.

pBD-GAL4-REA was constructed by subcloning the EcoRI-XbaI blunt insert into pBD-GAL4 (Stratagene) by EcoRI and SmaI digestion. pCMV-PTα was constructed by releasing the PTα cDNA from pAD-GAL4-PTα by EcoRI-XhoI digestion and inserting into EcoRI and SalI-digested pCMV5. pBD-GAL4-PTα and pGEX-4T-1-PTα were constructed by subcloning the EcoRI and XhoI PTα generated from PCR using specific primers (forward, 5′-GTG AAT TCT GCC CCA CCA TGT C-3′; reverse, 5′-GCC TCG AGC TCA GTC ATC CTC GTC GGT-3′) into the EcoRI and XhoI sites of pBD-GAL4 (Stratagene) and pGEX-4T-1 (Amersham-Pharmacia). Reactions with constructed forward and reverse PCR primers were performed using VENT DNA polymerase from New England Biolabs. PTα was subcloned into pBK (Stratagene) by digestion with EcoRI and XbaI of pCMV5-PTα. pM-PTα was constructed by releasing the insert from pBK-PTα with EcoRI and XbaI and subcloning into the pM vector that contains the Gal4 DNA binding domain (Clontech). pM-ERDEF was subcloned into the pM vector with EcoRI and MluI using the PCR product of the DEF domain of ERα (amino acids 263 to 595) obtained with specific primers (forward, 5′-GGA ATT CAG AAT GTT GAA ACA CAA GCG C-3′; reverse, 5′-CGT ACG ACG CGT GAC TGT GGC AGG AAA CCC TCT GCC-3′). pVP16-SRC-1NRD was subcloned into the pVP16 vector (Clontech) by releasing the nuclear receptor domain (NRD) (amino acids 629 to 831) from pET15-SRC-1NRD, kindly provided by John Katzenellenbogen (University of Illinois, Urbana) by NdeI (blunt) and XhoI digestion and inserting into SmaI- and SalI-digested pVP16. The p53 cDNA in the pM vector and pG5-CAT (which contains five Gal4 DNA response elements) were from Clontech. The antisense REA was subcloned into pCMV5 vector with EcoRI and XbaI blunt insert. All cloning was verified by sequencing. pBK-REA, pBK-REA(1–174), pBK-REA(1–199), pBK-REA(1–260), pBK-REA(19–299), and pBK-REA(65–299) were subcloned into pBK by EcoRI and XbaI as described previously (26). The pCMV5 expression vectors for the human ERα, human ERβ (530 residues), human progesterone receptor (PR) pCMV5-PRb, human glucocorticoid receptor (GR) pRSV-GR, and pCMV-REA have been described (26). The expression vector, pBK-CMV-SRC-1 (28), was kindly provided by Ming Tsai and Bert O'Malley (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Tex.). The reporter vector, pGAL4-SV40-Luc, was kindly provided by Mitchell Lazar (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia). The estrogen response element (ERE)-containing reporters (ERE)2-TATA-CAT, (ERE)2-pS2-CAT, and (PRE)2-TK-CAT have been described previously (30, 31). The TGF-β3-CAT reporter has been described (46) and was kindly provided by Na Yang (Eli Lilly Co., Indianapolis, Ind.). Plasmid pCMVβ (Clontech) was used as a β-galactosidase internal control for transfection efficiency, and all chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) activity or luciferase measurements were corrected for β-galactosidase activity (18, 31).

cDNA library construction.

cDNA was prepared from MCF-7 cells and ligated into the HybriZAP vector (Stratagene) to generate a primary lambda library as described (26). This library was amplified and converted by in vivo excision to a pAD-GAL4 phagemid library. The average insert size in the phagemid library is 1.4 kb.

Yeast two-hybrid screening.

Yeast strain YRG2 (Stratagene) containing pBD-GAL-REA was transformed with the human MCF-7 cDNA library in pAD-GAL4 and plated on medium lacking histidine and supplemented with 3-amino-triazole (Sigma) to decrease histidine background. HIS3+ colonies were measured for β-galactosidase activity using the filter lift assay (42). HIS3+ colonies exhibiting high β-galactosidase activity (LacZ+ colonies) were further characterized. To recover library plasmids, total DNA from HIS3+ LacZ+ colonies was isolated and used to transform Escherichia coli XLI-Blu MRF′ (Stratagene). To ensure that the correct cDNAs were identified, library plasmids isolated were transformed into YRG2 containing pBD-GAL-REA and plated into medium lacking histidine and supplemented with 3-amino-triazole. β-Galactosidase activity was determined from HIS3+ colonies using both the filter lift assay and liquid assay (42).

Cell culture and transfection.

MCF-7 human breast cancer cells, Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, and MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells were maintained in cell culture and transfected by the CaPO4 coprecipitation method (27, 31) or lipofectin method (3) as previously described (24). CHO cells were plated at 1.8 × 105 per 60-mm plate and transfected 48 h later with 2 μg of (ERE)2-TATA-CAT or 2 μg of (PRE)2-TK-CAT, 0.4 μg of pCMVβ and with receptor expression plasmid, either 5 ng of pCMV5-ERα, 10 ng of pCMV5-ERβ, 250 ng of pRSV-GR, or 50 ng of pCMV5-PRb, and carrier DNA to 8 μg of total DNA per plate. MDA-MB-231 cells in 24-well plates were transfected with the ERE-containing reporter construct [(ERE)2-pS2-CAT and 5 ng of CMV5-ERα expression vector or 2 μg of TGF-β3-CAT and 0.2 μg of CMV-ERα], 0.4 μg of pCMVβ (β-galactosidase internal control plasmid), and carrier DNA. For the mammalian two-hybrid assays, CHO cells in 24-well plates were transfected with 0.2 μg of pM-ER, 0.2 μg of pVP16-SRC-1, 1 μg of pG5-CAT, 0.2 μg of pCMVβ, and carrier DNA. At 8 h after transfection, cells were treated with hormone or control vehicle. Cells were harvested 24 h after hormone treatment, and cell extracts were prepared. β-Galactosidase activity, which was measured to normalize for transfection efficiency, and CAT activity were assayed as described (31).

Northern blot analysis.

Gel-purified REA and 36B4 cDNAs were random- primer labeled using the Redi-Prime II DNA-labeling kit from Amersham. Hybridization of RNA from 231 breast cancer cells was performed in Expresshyb hybridization solution (Clontech) at 65°C for 18 h. Signal intensity was quantified by phosphorimager analysis and normalized using 36B4 RNA as the internal control.

In vitro translation.

In vitro translation of REA, ERα, SRC-1, and PTα was performed (18) using the Promega TNT kit.

In vitro protein interaction assays.

The full-length PTα cDNA was inserted into the pGEX-4T-1 expression vector (Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.). Glutathione S-transferase (GST)–PTα, GST-REA, and GST-ERα were individually expressed in the BL21(DE3) strain of Escherichia coli (Novagen, Madison, Wis.), and each was purified to homogeneity by glutathione-agarose affinity chromatography. GST, GST-PTα, GST-REA, or GST-ERα was bound to glutathione-agarose and equilibrated with 1× GBB (20 mM Tris [pH 7.6], 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.2% NP-40, and protease inhibitors [4.0 μg of aprotinin, 2.0 μg of leupeptin, and 1.0 μg of pepstatin A per ml plus 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF)]). Various amounts of [35S]methionine-labeled proteins or radioinert proteins, as indicated in each figure legend, were incubated with the immobilized GST fusion proteins in 100 μl of 1× GBB for 1 h at 4°C. The beads were washed three times with 1× GBB (0.5 ml) and twice with 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0) (0.5 ml) buffer. Bound proteins were eluted with 10 mM reduced glutathione in 50 mM Tris buffer. Eluted proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and visualized by autoradiography. Images were quantitated using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.).

Western analysis and immunoprecipitation assays.

The 231 and MCF-7 cells were harvested from 100-mm dishes and resuspended in 100 μl of lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, and 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], containing: 0.2 mM PMSF plus 5.0 μg of aprotinin, 2.0 μg of leupeptin, and 1.0 μg of pepstatin A per ml). Whole-cell extracts were obtained by subjecting cells to three rounds of freezing on dry ice and thawing at 37°C followed by centrifugation at 15,000 × g to remove cell debris. Approximately 200 μg of total cell extract was loaded on an SDS–15% polyacrylamide gel. Electrophoresis and Western blotting were done according to standard methods (41). Nitrocellulose blots were probed with the human PTα primary antibody (ImmunDiagnostik, Bensheim, Germany) at 2.0 μg/ml and then incubated with goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) at 1 μg/ml and detected with the ECL Plus Western blotting detection reagents (Amersham-Pharmacia). For immunoprecipitation, 231 and MCF-7 cell lysates (200 μg of total cell extract) were precleared by incubating overnight at 4°C with rabbit serum (Sigma), followed by 30 min of incubation with protein A-Sepharose (Zymed) and centrifugation at 10,000 × g to pellet the Sepharose (19). The supernatants were incubated with polyclonal PTα antibody (2.5 μg/ml) and 5 μl of either radiolabeled in vitro-translated ERα or REA for 1 h at 4°C. After incubation with protein A-Sepharose for 1 h at 4°C and centrifugation at 10,000 × g, the pellets were washed twice with wash buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl [pH 9], 0.5 M LiCl, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% NP-40) and twice with wash buffer containing 30% sucrose. The pellets were resuspended in SDS gel loading buffer, boiled at 100°C, and analyzed by electrophoresis on SDS–10% polyacrylamide gels under denaturing conditions. For coimmunoprecipitation of endogenous proteins, electrophoresis and Western blotting were done as above, and the blot was probed with the human REA antibody at 2.0 μg/ml and then incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG at 1 μg/ml and detected as above.

RESULTS

REA interacts with PTα in the yeast two-hybrid system.

To investigate the mechanism by which the ER-selective coregulator REA works, we used REA in a yeast two-hybrid screening analysis to identify REA-interacting proteins. Full-length REA was cloned into a GAL4 DNA binding domain yeast expression vector (pGAL4-DBD REA), and this was used as bait to screen an MCF-7 cell cDNA library. The cDNA library from MCF-7 breast cancer cells was constructed and introduced as a translational fusion with the GAL4 transactivating domain [GAL(AD)-cDNA] into the YRG2 yeast strain as previously described (26).

REA-interacting clones were identified by their ability to activate reporter constructs containing the UASGAL4 when cotransformed with GAL(DBD)-REA, and these were then isolated from HIS+ clones or clones that showed increased transcription from the lacZ reporter gene (lacZ+). In this way, we isolated a 1.1-kb clone that was sequenced and compared to the gene databank using the BLAST search program. This clone contained an open reading frame of 330 bp (109 amino acids) and showed 100% identity to PTα. Subsequent two-hybrid screenings with full-length PTα as bait pulled out REA from our MCF-7 cDNA library, confirming that this interaction was reproducible.

PTα enhances ER transcriptional activity but not the transcriptional activity of other nuclear hormone receptors.

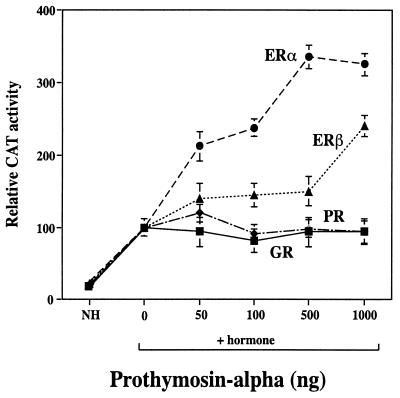

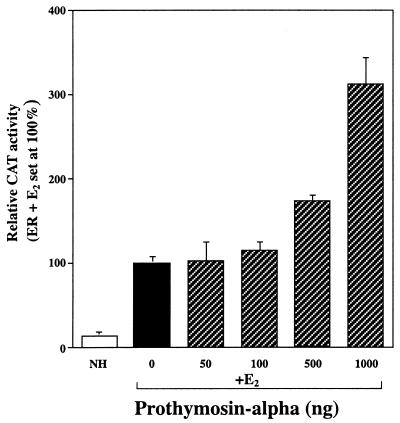

Transfection of PTα (Fig. 1) increased the transactivation activity of ER in mammalian cells, ERα more so than ERβ. In contrast to the stimulatory effect of PTα on ER, PTα had little or no effect on transcriptional activity of the PR or GR (Fig. 1) or the thyroid hormone receptor or retinoic acid receptor (data not shown). The ability of PTα to increase transcriptional activity by the ER was observed with reporter gene constructs containing both consensus estrogen response elements (Fig. 1) and response elements quite different from consensus elements, as in the transforming growth factor beta 3 (TGF-β3) promoter (Fig. 2) and was observed in several cell types (Fig. 1 and 2 and data not presented).

FIG. 1.

PTα increases transcriptional activity of ERs but has little stimulatory effect on PR or GR. The indicated nuclear receptor was transfected into CHO cells along with empty expression plasmid or with the indicated amounts of PTα expression plasmid and the appropriate hormone-responsive reporter gene construct (2ERE-TATA-CAT for ER and 2PRE-tk-CAT for PR or GR). Cells were treated with control vehicle and no hormone (NH) or with 10−8 M estradiol (for ER), 10−8 M R5020 (for PR), or 10−8 M dexamethasone (for GR), as appropriate. Cells transfected with the plasmids and no hormone showed no difference in reporter gene activity in the presence or absence of PTα. At 24 h after hormone treatment, CAT activity, corrected for differences in transfection efficiency with an internal control β-galactosidase reference standard, was determined. CAT activity of cells treated with hormone but receiving no added PTα (zero PTα) is set at 100. Values represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments.

FIG. 2.

PTα increases the transcriptional activity of the ER on the TGF-β3 promoter-reporter gene construct containing a nonconsensus estrogen-responsive region. ER-negative 231 breast cancer cells were transfected with ERα and the TGF-β3-CAT reporter in the presence and absence of estradiol (E2) (10−8M) and control 0.1% ethanol vehicle (NH) or with increasing amounts of PTα expression vector and estradiol treatment. CAT activity was determined. ER plus estradiol activity in the absence of added PTα was set at 100%. Values are the mean ± SD of three determinations.

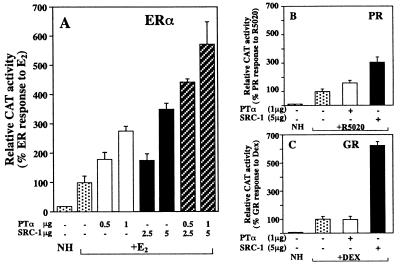

We next compared the stimulatory activity of PTα and the steroid receptor coactivator SRC-1 (28) with several steroid hormone receptors (Fig. 3). SRC-1 enhanced the transcriptional activity of ER, PR, and GR, as expected, while PTα had only a slight effect on transcriptional activity of PR and no effect on transcriptional activity of GR. On ER, PTα or SRC-1 increased activity three- to fourfold, and the effects of PTα and SRC-1 appeared to be additive.

FIG. 3.

PTα stimulates transcriptional activity of the ER while SRC-1 stimulates transcriptional activity of ER, PR, and GR. Transfections were performed in CHO cells with ER (A), PR (B), or GR (C) and the appropriate reporter gene construct in the presence or absence of added PTα and/or SRC-1 expression plasmid. Relative CAT activity, normalized for β-galactosidase internal transfection efficiency control, was determined and is expressed relative to the hormone response of the receptor with ligand but no added PTα or SRC-1, being set in all cases at 100%. NH, no hormone added.

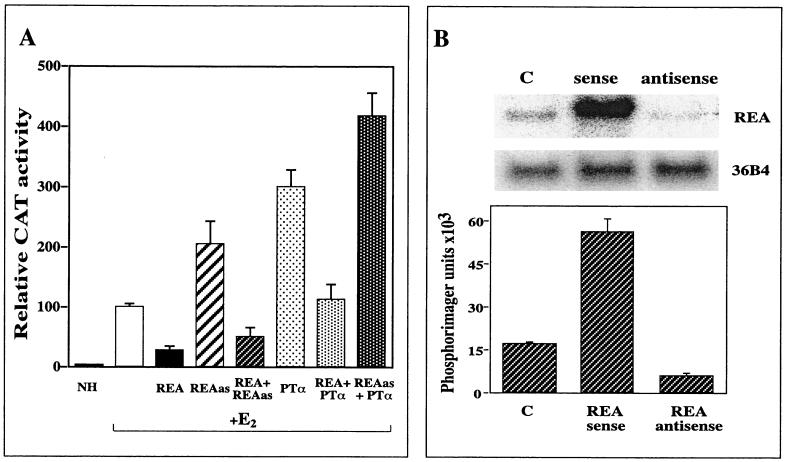

REA suppresses the stimulatory effect of PTα on transcriptional activity of the ER.

As shown in Fig. 4, REA markedly suppressed the activity of the estradiol-occupied ER, and transfection of an expression vector encoding antisense REA enhanced the transcriptional response to the estradiol-ER complex, suggesting that endogenous cell REA normally suppresses the transcriptional activity of the ER. In addition, Fig. 4 shows that the increased transcriptional activity of the ER stimulated by PTα is suppressed by REA, while PTα in combination with antisense REA further stimulates the activity of the hormone-occupied ER. In keeping with this, Fig. 4B shows that transfection with antisense REA reduced endogenous REA mRNA levels below one-third of the control, while transfection with sense REA increased REA mRNA levels about threefold. These observations suggest that PTα and REA (which directly interact in GST pulldown experiments; see below) are both important factors in modulating the activity of the ER. Thus, binding up and neutralizing the inhibitory activity of REA, as observed with PTα, and eliminating REA through the use of antisense REA allowed the greatest magnitude of response to estradiol.

FIG. 4.

Effect of REA, antisense REA, and PTα on the transcriptional response of the estrogen-occupied ER. (A) Transfections were carried out in 231 cells with ERα expression plasmid and with the (ERE)2-pS2-CAT and internal control β-galactosidase reporters, in the presence and absence of expression plasmids encoding REA, antisense REA (REAas), and PTα as indicated. NH, no hormone. CAT activity is reported relative to the response to estradiol (E2) in the presence of ERα alone, which is set at 100%. (B) Northern blot analysis was performed after transfection of either pCMV-REA or pCMV-REA antisense to monitor the level of REA mRNA. Values represent the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. C, control empty vector transfected.

PTα interacts with REA but not with ER in GST pulldown assays.

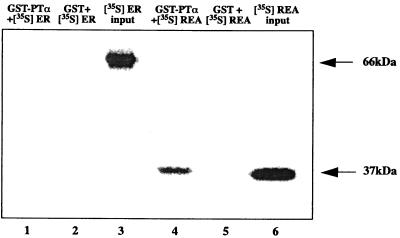

The ability of PTα and REA or ER to directly interact was examined in vitro using a protein-protein interaction assay in which the affinity matrix was a GST fusion protein with PTα bound to glutathione agarose (Fig. 5). In vitro-transcribed and translated [35S]REA was retained by the GST-PTα, whereas REA was not retained on the GST column alone. In contrast to the observed interaction between REA and PTα, in vitro-transcribed and translated [35S]ERα did not interact with the GST-PTα fusion protein or with GST alone.

FIG. 5.

GST pulldown assays demonstrating that PTα binds to REA but not ER. GST fusion protein with PTα was incubated with [35S]REA or [35S]ER made by in vitro transcription-translation. The interaction of radiolabeled REA or radiolabeled ER with GST alone was also monitored and found to be negative. Lanes 3 and 6 show the input (20%) radiolabeled ER and radiolabeled REA, respectively. Arrows indicate the positions of REA (37 kDa) and ER (66 kDa).

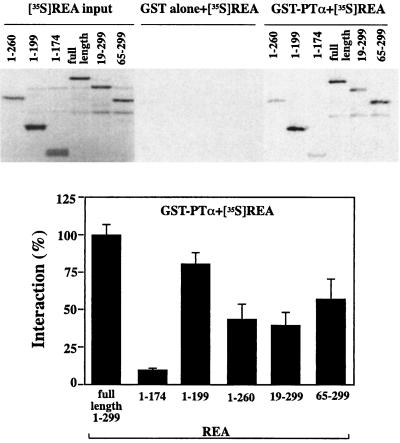

To identify the regions of REA involved in the interaction with PTα, we did additional GST pulldown assays with full-length PTα and various N- and C-terminally truncated REA proteins (Fig. 6). The data suggest that the strength of interaction is determined by more than one domain of REA. The N-terminal residues 1 to 174 REA interacted very poorly, while the presence of additional sequence (1 to 199 or 1 to 260) resulted in improved interaction. Interestingly, however, residues 1 to 199 showed greater interaction than residues 1 to 260, indicating that amino acids 175 to 199 and 200 to 260 might harbor domains positively and negatively affecting interaction with PTα. The deletion of amino acids 1 to 18 or 1 to 64 from the full-length REA impaired the interaction with PTα, suggesting that both N- and C-terminal portions of REA may collaborate in promoting optimal interaction with PTα. It is of interest that the C-terminal half of REA is the portion most crucial for interaction with the ER (26).

FIG. 6.

Mapping the regions of REA that interact with PTα. GST pulldown assays were performed using GST fused to full-length PTα or GST alone, incubated with radiolabeled full-length REA or REAs truncated to contain the indicated residues. Upper panel shows an SDS gel from a representative experiment. The lower panel summarizes data (mean ± SD) from three separate experiments. Each value was determined from the pulldown signal normalized to input for each REA. Interaction of full-length [35S]REA with GST-PTα has been calculated in the same way and is set at 100%.

PTα does not show intrinsic transcription activation activity when tethered to the GAL4 DNA binding domain.

The ability of PTα or p53 (as a positive control) to stimulate the transcription of a GAL4-responsive reporter, GAL4-SV40-Luc, was tested in transiently transfected 231 breast cancer cells. The data (not shown) indicated that PTα, when tethered to the GAL4 DNA binding domain, did not stimulate transcriptional activity, while the tumor suppressor transcription factor p53 did so very effectively. Thus, we further examined the interactions between REA and PTα and the coactivator SRC-1 in order to understand the mechanism by which PTα enhanced ER transactivational ability.

Investigation of the interactions among ER, PTα, REA, and SRC-1.

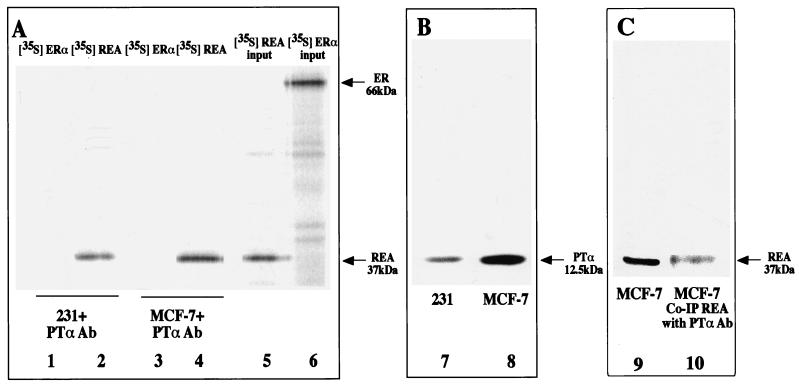

In addition to directly interacting in GST pulldown assays, PTα and REA were found to interact in cell extracts where REA was coimmunoprecipitated with PTα using PTα-specific polyclonal antibody (Fig. 7). Incubation of MCF-7 or 231 human breast cancer cell extracts containing endogenous PTα with radiolabeled in vitro-transcribed and translated [35S]REA or [35S]ERα showed that REA was immunoprecipitated along with PTα from cell extracts, whereas ERα did not coimmunoprecipitate with PTα (Fig. 7A, lanes 1 to 6). Figure 7B (lanes 7 and 8) indicates that the PTα polyclonal antibody selectively detects PTα (a 12.5-kDa protein) in cell extracts from 231 and MCF-7 cells. In a separate experiment (not shown), [35S]REA was not immunoprecipitated by PTα antibody in the absence of cell extract, indicating that there is no cross-reactivity of the PTα antibody with REA. In Fig. 7C, we show that endogenous REA (from MCF-7 breast cancer cells) is immunoprecipitated with PTα antibody. About one-third of the cellular REA is coimmunoprecipitated with PTα antibody and is then detectable on the Western blot with REA antibody (Fig. 7C, lanes 9 and 10). No endogenous ERα from MCF-7 cells was immunoprecipitated with PTα antibody (data not shown). These findings support the in vitro GST pulldown assays indicating interaction between PTα and REA but no interaction between PTα and ER.

FIG. 7.

REA but not ER is coimmunoprecipitated along with endogenous PTα present in 231 and MCF-7 breast cancer cells using PTα polyclonal antibody. (A and B) Extracts were prepared from 231 and MCF-7 breast cancer cells and incubated with [35S]REA or [35S]ERα prepared by in vitro transcription-translation. (A) Lanes 1 to 4, addition of PTα antibody (Ab) resulted in immunoprecipitation of [35S]REA but not [35S]ERα. Lanes 5 and 6, input (20%) radiolabeled REA and ER, respectively. (B) Lanes 7 and 8, polyclonal antibody to PTα is selective for PTα (12.5 kDa), as this is the only protein detected in cell extracts from 231 and MCF-7 cells. (C) MCF-7 cell extract was separated on an SDS gel, and endogenous REA was detected with specific antibody to REA (lane 9). In lane 10, REA is shown to be coimmunoprecipitated (Co-IP) with PTα. An equal amount of MCF-7 cell extract was incubated with PTα antibody (Ab), and the immunoprecipitate was then analyzed by Western blot using antibody to REA.

GST pulldown competition assays (Fig. 8) showed that ERα binds to GST-REA in the presence of estradiol and that increasing the amount of radioinert PTα prevents radiolabeled ER from binding to REA, implying that REA binding to ER and to PTα is mutually competitive.

FIG. 8.

GST pulldown competition assay shows that ERα binds to GST-REA in the presence of estradiol and that increasing PTα reduces radiolabeled ER binding to REA, implying that PTα binds to REA and prevents ER from binding to REA. GST-REA was incubated with [35S]ERα in the presence of estradiol (E) and increasing amounts (1:1, 1:2, and 1:3, ER/PTα) with radioinert PTα made by in vitro transcription and translation. Data are shown from one of three experiments, each of which gave similar results. Autoradiographic data for [35S]ER are shown across the top and quantitated in the bar graph below.

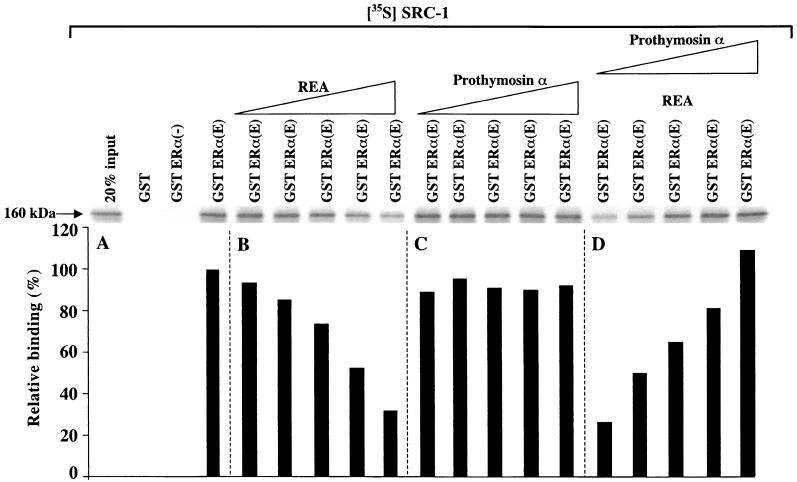

Since our previous work on REA (26) indicated functional competition between REA and the steroid receptor coactivator SRC-1 for regulation of transcriptional activity of the ER, we performed GST pulldown assays with GST-ERα and radiolabeled SRC-1 in the absence and presence of increasing amounts of radioinert REA or PTα. As shown in Fig. 9A, [35S]SRC-1 interacts well with GST-ERα in the presence of estradiol, while essentially no interaction is observed in the absence of estradiol. Interestingly, REA competitively reduces the binding of SRC-1 to the ER (Fig. 9B), while increasing levels of PTα have no effect on the interaction of radiolabeled SRC-1 with the ER (Fig. 9C). Also, as shown in Fig. 9D, the interaction of SRC-1 with ER in the presence of a fixed amount of radioinert REA, which suppresses radiolabeled SRC-1 interaction with ERα to a 20% level, can be increasingly reversed in the presence of increasing concentrations of radioinert PTα. These findings indicate that REA and SRC-1 mutually compete for binding to ERα, while PTα does not compete with SRC-1 for binding to the ER. Rather, as Fig. 9D indicates, PTα can recruit REA away from ERα, thereby allowing increased binding of SRC-1 to the ER. These data suggest a model for the mutual competition of REA and SRC-1 for binding to the ER and its modulation by PTα (see Discussion).

FIG. 9.

GST pulldown assays with GST-ERα and radiolabeled SRC-1 alone (A) or in the presence of increasing amounts of radioinert REA (B) or PTα (C) indicate that REA and SRC-1 mutually compete for binding to ERα, while PTα does not compete with SRC-1 for binding to the ER; PTα can recruit REA away from ER, allowing increased binding of SRC-1 to ER (D). (A) In vitro-translated, [35S]methionine-labeled SRC-1 (160 kDa) was incubated with the hormone-binding domain of ERα (residues 282 to 595) fused to GST (GST-ERα) (lanes 3 and 4) in the presence of 0.1% ethanol control vehicle (−) or 10−6 M estradiol (E) or with GST alone (lane 2). (B and C) In vitro-translated, [35S]methionine-labeled SRC-1 was incubated with GST-ERα in the presence of 10−6 M estradiol (E) and in the presence of increasing amounts (1:1, 1:2, 1:3, 1:4, and 1:5) of in vitro-translated radioinert REA (B, lanes 5 to 9) or in vitro-translated, radioinert PTα (C, lanes 10 to 14). (D) GST-ERα was incubated with radiolabeled SRC-1 in the presence of a fixed amount (1:5) of in vitro-translated, radioinert REA and increasing amounts (1:1, 1:2, 1:3, 1:4, and 1:5) of in vitro-translated radioinert PTα (lanes 15 to 19). (D) PTα can bind and sequester REA away from ERα, thereby allowing increasing amounts of radiolabeled SRC-1 to bind to the GST-ERα. A representative experiment is shown. The autogradiographic data for [35S]SRC-1 (160 kDa) are shown across the top, with the data quantitated in the bar graph below. Similar results were obtained in two repeat experiments.

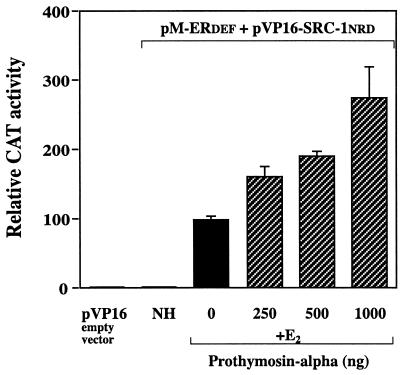

PTα increases the interaction of SRC-1 with ER.

Using a mammalian two-hybrid interaction assay with ER (domains D, E, and F, amino acids 263 to 595) and the nuclear receptor domain of SRC-1 (amino acids 629 to 831), increasing concentrations of PTα were found to enable a greater interaction between ER and SRC-1 and did so in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 10). This suggests that at high cellular levels of PTα, REA will be sequestered away from ER, allowing more SRC-1 to bind to ER, followed by increased transcriptional activation.

FIG. 10.

Mammalian two-hybrid assay showing that PTα increases the interaction of SRC-1 with ER. Transfection of pM-ERDEF, pVP16-SRC-1NRD, and pG5-CAT in the absence and presence of increasing amounts of pCMV-PTα was performed in CHO cells. Relative CAT activity, normalized for the β-galactosidase internal control, was determined and is expressed relative to the response of the receptor and SRC-1 with estradiol (E2) but no added PTα, which is set at 100%. NH, no hormone added; pVP16 empty vector was used as a control.

DISCUSSION

The studies presented in this work indicate that PTα acts to selectively enhance ER transcriptional activity by an intriguing mechanism, by modulating the mutually competitive binding of REA and SRC-1 to ER. In earlier studies, we showed that REA is a selective repressor of ER transcriptional activity, although it did not have intrinsic repressive activity when tethered to the heterologous GAL4 DNA binding domain (26). To help us understand the mechanism by which REA suppresses the activity of the ER, we used REA as a bait in a yeast two-hybrid screening to identify REA-interacting proteins. PTα was found reproducibly to interact with REA both in the yeast two-hybrid assay and in GST pulldown assays and coimmunoprecipitation assays in mammalian cells.

PTα is a known protein that has an identified function in chromatin remodeling by modulating the interaction of histone H1 with chromatin (6, 10, 14, 40). In addition to preferentially binding histone H1, PTα also displays high affinity for histones H3 and H4 (6). It has also been suggested to stimulate the phosphorylation of transcription factors such as E2F, although this is controversial (7). PTα is a small, 109-amino-acid protein that is rich in acidic (aspartic acid and glutamic acid) residues such as are also found in the yeast transcription-regulating proteins GAL4 and GCN4 (13), the viral protein VP16, and the N terminus of the GR (11, 12). Interestingly, PTα is a c-myc target gene (5), and its level is associated with the proliferative state, being highest at the S/G2 phase of the cell cycle (38). Its level is also higher in malignant breast tumors than in benign breast lesions or in adjacent normal breast tissue (4, 36), and it may be a prognostic factor in breast cancer, as there is an association between PTα level and increased risk of death from breast cancer. There is also evidence that PTα binds to tRNAs (20), that PTα contains phosphorylated residues, including acylphosphates (phosphoglutamic acid), and that the activity of PTα may involve turnover of its acylphosphates (34, 39) and may fuel an energy-requiring step in the production or processing of RNA (32).

Our studies have elucidated a new role for PTα. We have found that increasing cellular levels of PTα by transfection increased the transcriptional activity of the ER, whereas PTα had little or no effect on transcriptional activity of other nuclear hormone receptors, such as the PR and GR. The selective stimulatory activity of PTα on the ER contrasts with the more general ability of the steroid receptor coactivator SRC-1 to enhance transcriptional activity of all the nuclear receptors.

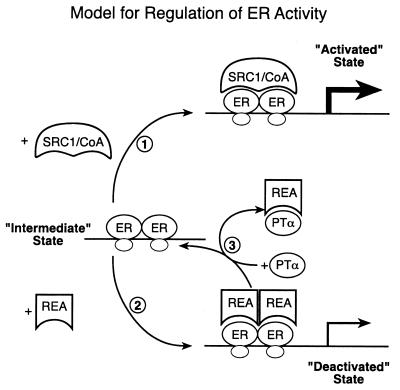

It is of note that PTα binds to REA but not to ER. The binding of REA to ER and to PTα is mutually competitive, as is the binding of REA and SRC-1 to ER. The fact that PTα has no intrinsic transcriptional activation function yet selectively enhances ER transcription, together with the mutually competitive binding results noted above, can be rationalized by a simple model, shown in Fig. 11. In this model, ER is shown to interact either with SRC-1 (or related p160 coactivators) or with REA, as we have previously shown (26). Thus, the selective effect of REA in repressing estrogen action results from its selective inhibition of coactivator binding to ER.

FIG. 11.

Model showing that REA and SRC-1 compete for binding to the ER and that PTα recruits REA away from ER, antagonizing the repressive activity of REA and enabling PTα to enhance ER transactivation activity. REA blocks coactivator SRC-1 binding and PTα acts in competition with REA to regulate transcriptional effectiveness, interfering with REA binding to ER. Therefore, by acting as an inhibitor of an anticoactivator (REA), PTα acts to enhance transcriptional activity of the liganded ER.

REA binding to ER is also mutually competitive with its binding to PTα, whereas PTα binds to neither ER nor SRC-1. Thus, as cellular levels of PTα increase, this protein will increasingly bind up REA and sequester it away from ER. This would allow ER to bind to SRC-1 and result in enhanced transcription. The fact that PTα selectively activates ER transcription is the result, at least in part, of the selectivity of REA binding to ER. Since REA does not bind to other nuclear receptors or repress their transcriptional effectiveness (29), its binding to PTα would be of no consequence to the activity of these receptors. The repressor of ER activity, REA, thus functions as an anticoactivator; PTα, by blocking the binding of REA to ER, is able to selectively enhance ER transcriptional activity and thus functions as an anticoactivator inhibitor. This is schematically illustrated in Fig. 11. While we know the stoichiometry of SRC-1 binding to ER (1 molecule of SRC-1 per ER dimer [9]), we do not yet know the stoichiometry of REA-ER interaction or the stoichiometry of REA-PTα interaction. From the sizes of these proteins, we have arbitrarily drawn these as 2 REA molecules per ER dimer and 1 REA to 1 PTα molecule in Fig. 11. Future studies will seek to define this aspect more precisely.

It is known that the activity of nuclear hormone receptors is markedly modulated by coactivators and corepressors (2, 25, 33, 43). Hence, the relative levels of these coregulators are thought to be important determinants of hormonal effectiveness in different tissues. It is well known that the activity of estrogens can be quite different in various target cells (15–17, 23, 37). This may in part be explained by differing levels of coactivators and corepressors. Our studies reveal additional dimensions to this aspect of the regulation of receptor activity, as we have identified two other proteins, REA and PTα, that can modulate the magnitude of ER transcriptional activity. Neither of these proteins has intrinsic activation or repression functions, yet they have important effects on ER activity. They act by either interfering with (REA) or enabling (PTα) the interaction of ER with coactivators such as SRC-1.

The finding that expression of antisense REA elicits higher ER transcriptional activity provides strong evidence that REA, at levels endogenously present in cells, functions to moderate the activity of ER. Since we have shown that PTα counters the repressive activity of REA, we would expect that cellular changes that increase PTα and/or decrease REA would enhance estrogen action, whereas changes that decrease PTα and/or increase REA would reduce estrogen action. In this regard, it is interesting to note that PTα levels are increased in rapidly proliferating cells (1, 6, 10, 22, 38, 43) and in response to estrogen treatment of ER-containing breast cancer cells (P. Martini, K. Ekena, R. Delage-Mourroux, M. Montano, W. Harrington, and B. S. Katzenellenbogen, Abstr. 81st Annu. Meet. Endocrine Soc. 1999, abstr. OR1-2, p. 63, 1999) and neuroblastoma cells (8). Thus, PTα has the potential of magnifying the effectiveness of estrogen in stimulating transcriptional activity in rapidly proliferating cells by enhancing ER-coactivator interactions.

Changes in the levels of PTα, REA, and coactivators such as SRC-1 as a function of cell cycle and proliferative state or during development could modulate the ER transcriptional activity associated with these changing cellular states. Additional studies addressing the regulation of expression of these genes will be important in understanding further how activity of the ER is influenced not only by ligands, but also by the tripartite interactions of receptor (17) with these coregulators and activity-modulating proteins.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grants from the NIH (CA18119, CA60514, and 5T32 CA09067) and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation and a postdoctoral fellowship from the Susan G. Komen Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bustelo X R, Otero A, Gomez-Marquez J, Freire M. Expression of the rat prothymosin alpha gene during T-lymphocyte proliferation and liver regeneration. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:1443–1447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen J D, Li H. Coactivation and corepression in transcriptional regulation by steroid/nuclear hormone receptors. Crit Rev Eukaroyt Gene Expression. 1998;8:169–190. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v8.i2.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng P-W. Receptor ligand-facilitated gene transfer: enhancement of liposome-mediated gene transfer and expression by transferrin. Human Gene Ther. 1996;7:275–282. doi: 10.1089/hum.1996.7.3-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costopoulou D, Leondiadis L, Czarnecki J, Ferderigos N, Ithakissios D S, Livaniou E, Evangelatos G P. Direct ELISA method for the specific determination of prothymosin alpha in human specimens. J Immunoassay. 1998;19:295–316. doi: 10.1080/01971529808005487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desbarats L, Gaubatz S, Eilers M. Discrimination between different E-box-binding proteins at an endogenous target gene of c-myc. Genes Dev. 1996;10:447–460. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diaz-Jullien C, Perez-Estevez A, Covelo G, Freire M. Prothymosin alpha binds histones in vitro and shows activity in nucleosome assembly assay. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1296:219–227. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(96)00072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enkemann S A, Pavur K S, Ryazanov A G, Berger S L. Does prothymosin alpha affect the phosphorylation of elongation factor 2? J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18644–18650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garnier M, Di Lorenzo D, Albertini A, Maggi A. Identification of estrogen-responsive genes in neuroblastoma SK-ER3 cells. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4591–4599. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-12-04591.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gee A C, Carlson K E, Martini P G, Katzenellenbogen B S, Katzenellenbogen J A. Coactivator peptides have a differential stabilizing effect on the binding of estrogens and antiestrogens with the estrogen receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:1912–1923. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.11.0373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomez-Marquez J, Rodriguez P. Prothymosin α is a chromatin-remodeling protein in mammalian cells. Biochem J. 1998;333:1–3. doi: 10.1042/bj3330001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hahn S. Structure(?) and function of acidic transcription activators. Cell. 1993;72:481–483. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90064-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hollenberg S M, Evans R M. Multiple and cooperative trans-activation domains of the human glucocorticoid receptor. Cell. 1988;55:899–906. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hope I A, Struhl K. Functional dissection of a eukaryotic transcriptional activator protein, GCN4 of yeast. Cell. 1986;46:885–894. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karetsou Z, Sandaltzopoulos R, Frangou-Lazaridis M, Lai C Y, Tsolas O, Becker P B, Papamarcaki T. Prothymosin alpha modulates the interaction of histone H1 with chromatin. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:3111–3118. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.13.3111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katzenellenbogen B S. Estrogen receptors: bioactivities and interactions with cell signaling pathways. Biol Reprod. 1996;54:287–293. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod54.2.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katzenellenbogen B S, Montano M M, Ekena K, Herman M E, McInerney E M. Antiestrogens: mechanisms of action and resistance in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1997;44:23–38. doi: 10.1023/a:1005835428423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katzenellenbogen J A, O'Malley B W, Katzenellenbogen B S. Tripartite steroid hormone receptor pharmacology: interaction with multiple effector sites as a basis for the cell- and promoter-specific action of these hormones. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:119–131. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.2.8825552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lazennec G, Ediger T R, Petz L N, Nardulli A M, Katzenellenbogen B S. Mechanistic aspects of estrogen receptor activation probed with constitutively active estrogen receptors: correlations with DNA and coregulator interactions and receptor conformational changes. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:1375–1386. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.9.9983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LeGoff P, Montano M M, Schodin D J, Katzenellenbogen B S. Phosphorylation of the human estrogen receptor: identification of hormone-regulated sites and examination of their influence on transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4458–4466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lukashev D E, Chichkova N V, Vartapetian A B. Multiple tRNA attachment sites in prothymosin alpha. FEBS Lett. 1999;451:118–124. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00580-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mangelsdorf D J, Thummel C, Beato M, Herrlich P, Schutz G, Umesono K, Blumberg B, Kastner P, Mark M, Chambon P, Evans R M. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83:835–839. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manrow R E, Sburlati A R, Hanover J A, Berger S L. Nuclear targeting of prothymosin alpha. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:3916–3924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDonnell D P. The molecular pharmacology of SERMs. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 1999;10:301–311. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(99)00177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McInerney E M, Weis K E, Sun J, Mosselman S, Katzenellenbogen B S. Transcription activation by the human estrogen receptor subtype β (ERβ) studied with ERβ and ERα receptor chimeras. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4513–4522. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.11.6298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKenna N J, Lanz R B, O'Malley B W. Nuclear receptor coregulators: cellular and molecular biology. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:321–344. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montano M M, Ekena K, Delage-Mourroux R, Chang W, Martini P, Katzenellenbogen B S. An estrogen receptor-selective coregulator that potentiates the effectiveness of antiestrogens and represses the activity of estrogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6947–6952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montano M M, Katzenellenbogen B S. The quinone reductase gene: a unique estrogen receptor-regulated gene that is activated by antiestrogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2581–2586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Onate S A, Tsai S Y, Tsai M J, O'Malley B W. Sequence and characterization of a coactivator for the steroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science. 1995;270:1354–1357. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rachez C, Lemon B D, Suldan Z, Bromleigh V, Gamble M, Naar A M, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Freedman L P. Ligand-dependent transcription activation by nuclear receptors requires the DRIP complex. Nature. 1999;398:824–828. doi: 10.1038/19783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reese J C, Katzenellenbogen B S. Examination of the DNA binding abilities of estrogen receptor in whole cells: implications for hormone-independent transactivation and the action of the pure antiestrogen ICI164,384. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:4531–4538. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.10.4531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schodin D J, Zhuang Y, Shapiro D J, Katzenellenbogen B S. Analysis of mechanisms that determine dominant negative estrogen receptor effectiveness. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:31163–31171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tao L, Wang R H, Enkemann S A, Trumbore M W, Berger S L. Metabolic regulation of protein-bound glutamyl phosphates: insights into the function of prothymosin alpha. J Cell Physiol. 1999;178:154–163. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199902)178:2<154::AID-JCP4>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torchia J, Glass C, Rosenfeld M G. Co-activators and co-repressors in the integration of transcriptional responses. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:373–383. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trumbore M W, Wang R H, Enkemann S A, Berger S L. Prothymosin alpha in vivo contains phosphorylated glutamic acid residues. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26394–26404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsai M-J, O'Malley B W. Molecular mechanisms of action of steroid/thyroid receptor superfamily members. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:451–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.002315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsitsilonis O E, Bekris E, Voutsas I F, Baxevanis C N, Markopoulos C, Papadopoulou S A, Kontzoglou K, Stoeva S, Gogas J, Voelter W, Papamichail M. The prognostic value of alpha-thymosins in breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 1998;18:1501–1508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tzukerman M T, Esty A, Santiso-Mere D, Danielian P, Parker M G, Stein R B, Pike J W, McDonnell D P. Human estrogen receptor transactivational capacity is determined by both cellular and promoter context and mediated by two functionally distinct intramolecular regions. Mol Endocrinol. 1994;8:21–30. doi: 10.1210/mend.8.1.8152428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vareli K, Tsolas O, Frangou-Lazaridis M. Regulation of prothymosin alpha during the cell cycle. Eur J Biochem. 1996;238:799–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0799w.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang R H, Tao L, Trumbore M W, Berger S L. Turnover of the acyl phosphates of human and murine prothymosin alpha in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26405–26412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolffe A P, Hayes J J. Chromatin disruption and modification. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:711–720. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.3.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wrenn C K, Katzenellenbogen B S. Cross-linking of estrogen receptor to chromatin in intact MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1990;4:1647–1654. doi: 10.1210/mend-4-11-1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wrenn C K, Katzenellenbogen B S. Structure-function analysis of the hormone binding domain of the human estrogen receptor by region-specific mutagenesis and phenotypic screening in yeast. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24089–24098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu C L, Shiau A L, Lin C S. Prothymosin alpha promotes cell proliferation in NIH3T3 cells. Life Sci. 1997;61:2091–2101. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00882-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu L, Glass C K, Rosenfeld M G. Coactivator and corepressor complexes in nuclear receptor function. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:140–147. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(99)80021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang N N, Venugopalan M, Hardikar S, Glasebrook A. Identification of an estrogen response element activated by metabolites of 17-β-estradiol and raloxifene. Science. 1996;273:1222–1225. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5279.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]