Abstract

Introduction

There are few published empirical data on the effects of COVID‐19 on mental health, and until now, there is no large international study.

Material and methods

During the COVID-19 pandemic, an online questionnaire gathered data from 55,589 participants from 40 countries (64.85% females aged 35.80 ± 13.61; 34.05% males aged 34.90±13.29 and 1.10% other aged 31.64±13.15). Distress and probable depression were identified with the use of a previously developed cut-off and algorithm respectively.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated. Chi-square tests, multiple forward stepwise linear regression analyses and Factorial Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) tested relations among variables.

Results

Probable depression was detected in 17.80% and distress in 16.71%. A significant percentage reported a deterioration in mental state, family dynamics and everyday lifestyle. Persons with a history of mental disorders had higher rates of current depression (31.82% vs. 13.07%). At least half of participants were accepting (at least to a moderate degree) a non-bizarre conspiracy. The highest Relative Risk (RR) to develop depression was associated with history of Bipolar disorder and self-harm/attempts (RR = 5.88). Suicidality was not increased in persons without a history of any mental disorder. Based on these results a model was developed.

Conclusions

The final model revealed multiple vulnerabilities and an interplay leading from simple anxiety to probable depression and suicidality through distress. This could be of practical utility since many of these factors are modifiable. Future research and interventions should specifically focus on them.

Keywords: COVID-19, Depression, Suicidality, Mental health, Conspiracy theories, Mental disorders, Psychiatry, Anxiety

1. Introduction

While the COVID-19 pandemic started as an epidemic of an infectious agent, it soon gained a wider content and included all effects on all aspects of human life by this condition, even the overwhelming burst of information of questionable reliability and validity (‘infodemic’) (Asmundson and Taylor, 2021). The abuse of the terms ‘trauma’ and ‘PTSD’ is such an example. In this frame, mental health has gained a central position as an area which is expected to be affected by the pandemic because of its threatening nature as well as because of the profound impact on everyday life of people. Especially concerning the later, it has been suggested that lockdowns triggered feelings of loneliness, irritableness, restlessness, and nervousness in the general population (Saladino et al., 2020),

The overall opinion was that there could be long-lasting psychological scars and emotional wounds and this should be taken into consideration along with the fact that specifically depression is expected to be one of the top debilitating medical conditions and with the highest socioeconomic burden. There are many reports in the literature suggesting that the COVID‐19 outbreak triggered feelings of fear, worry, and stress, as responses to an extreme threat for the community and the individual with the general picture suggesting that more than 40% of the general population might experience high levels of anxiety or distress (Fullana et al., 2020; Fullana and Littarelli, 2021; Gonda and Tarazi, 2021; Vinkers et al., 2020). The issue of increased suicidality as a consequence of extreme stress and depression has been raised again (Courtet and Olie, 2021; Pompili, 2021). In addition, changes to social behavior, as well as working conditions, daily habits and routine have imposed secondary stress. Especially the expectation of an upcoming economic crisis and possible unemployment were stressful factors. The vast majority of studies reported a ‘tsunami’-scale impact on mental health. It is highly possible that this could be an exaggeration (Shevlin et al., 2021). Higher levels of anxiety, stress and depressive feelings have been reported, but it seems that this depends on the temporal situation and the specific events; response is by no means homogenous (Fancourt et al., 2021; Shevlin et al., 2021; Wong et al., 2020) (Mortier et al., 2021; Racine et al., 2021; Taquet et al., 2021). It is important to note that negative reports do exist, and they come from the study of carefully selected representative samples (van der Velden et al., 2020). Another important observation is that the population as a whole seemed to adjust rather well to the new situation and successfully cope with challenges at least in the middle term (Fancourt et al., 2021). Interestingly, some authors reported that negative affect decreased rather than increased during lockdowns (Foa et al., 2021; Recchi et al., 2020), Conspiracy theories and maladaptive behaviors were also prevalent, compromising the public defense against the outbreak.

At the end of the day, although are several empirical data papers, their methodology varies, it is very difficult to make comparisons among countries and it is also difficult to arrive at universally valid conclusions. Additionally, the literature is full of opinion papers, viewpoints, perspectives, guidelines and narrations of activities to cope with the pandemic. These borrow from previous experience with different pandemics and utilize common sense, but, as a result, they often obscure rather than clarify the landscape. The role of the mass and social media has been discussed but remains poorly understood in empirical terms.

An early meta-analysis reported high rates of anxiety (25%) and depression (28%) in the general population (Ren et al., 2020) while a second one reported that 29.6% of people experienced stress, 31.9% anxiety and 33.7% depression (Salari et al., 2020). Not only do we need more reliable and valid data, but we also need to identify risk and protective factors so as to be able to recommend measures that will eventually improve public health by preventing the adverse impact on mental health and simultaneously improve health-related behaviors.

The aim of the current study was to investigate the rates of distress, probable depression and suicidality and their changes in the adult population aged 18–69 internationally, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Secondary aims were to investigate their relations with several personal, interpersonal/social and lifestyle variables. The aim also included the investigation of the spreading of conspiracy theories concerning the COVID-19 outbreak and their relationship with mental health.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Method

The protocol used, is available in the webappendix; each question was given an ID code; these ID codes were used throughout the results for increased accuracy.

According to a previously developed method, (Fountoulakis et al., 2001, 2021, 2012) the cut-off score 23/24 for the CES-D and a derived algorithm were used to identify cases of probable depression. This algorithm utilized the weighted scores of selected CES-D items in order to arrive at the diagnosis of depression, and has already been validated. Cases identified by only either method, were considered cases of distress (false positive cases in terms of depression), while cases identified by both the cut-off and the algorithm were considered as probable depression. The STAI-S (Spielberger, 2005) and the RASS (Fountoulakis et al., 2012) were used to assess anxiety and suicidality respectively.

The data were collected online and anonymously from April 2020 through March 2021, covering periods of full implementation of lockdowns as well as of relaxations of measures in countries around the world. Announcements and advertisements were done in the social media and through news sites, but no other organized effort had been undertaken. The first page included a declaration of consent which everybody accepted by continuing with the participation.

Approval was initially given by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece and locally concerning each participating country.

2.2. Material

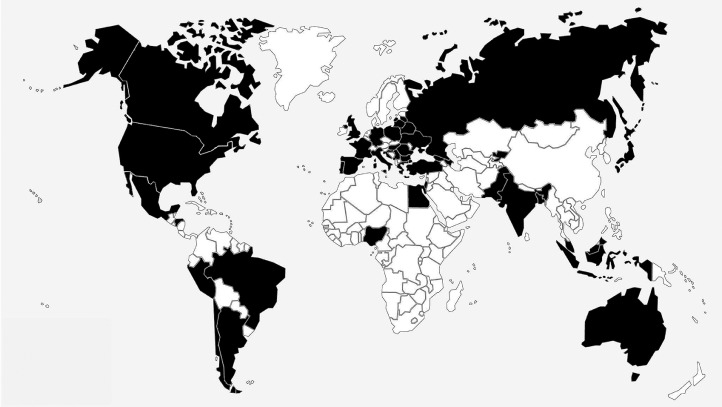

The study sample included data from 40 countries (Fig. 1 ) concerning 55,589 responses (64.85% females; 34.05% males; 1.10% other) to the online questionnaire. The contribution of each country and the gender and age composition are shown in Table 1 . Details concerning various sociodemographic variables (marital status, education, work etc. are shown in the webappendix, in webTables 1–9).

Fig. 1.

Map of the 40 participating countries.

Table 1.

List of participating countries by sex, with number of subjects and mean age.

| Males |

Females |

Non-binary gender |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Age |

Age |

Age |

||||||||||||

| Country | N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | N | % |

| Argentina | 439 | 20.14 | 44.53 | 14.39 | 1725 | 79.13 | 40.60 | 14.49 | 16 | 0.73 | 37.44 | 17.29 | 2180 | 3.92 |

| Australia | 21 | 30.43 | 33.67 | 8.05 | 48 | 69.57 | 32.63 | 7.89 | 0.00 | 69 | 0.12 | |||

| Azerbaijan | 70 | 19.89 | 36.20 | 10.33 | 280 | 79.55 | 37.71 | 11.46 | 2 | 0.57 | 26.00 | 0.00 | 352 | 0.63 |

| Bangladesh | 1681 | 55.42 | 24.09 | 5.24 | 1333 | 43.95 | 23.98 | 5.48 | 19 | 0.63 | 27.42 | 8.88 | 3033 | 5.46 |

| Belarus | 200 | 18.30 | 38.62 | 12.46 | 893 | 81.70 | 39.15 | 11.11 | 0.00 | 1093 | 1.97 | |||

| Brazil | 86 | 40.19 | 31.36 | 13.06 | 127 | 59.35 | 28.80 | 9.97 | 1 | 0.47 | 31.00 | 214 | 0.38 | |

| Bulgaria | 202 | 26.47 | 558 | 73.13 | 3 | 0.39 | 763 | 1.37 | ||||||

| Canada | 142 | 27.73 | 42.24 | 15.49 | 367 | 71.68 | 42.57 | 14.00 | 3 | 0.59 | 46.33 | 17.79 | 512 | 0.92 |

| Chile | 86 | 26.71 | 40.76 | 15.43 | 234 | 72.67 | 39.57 | 15.08 | 2 | 0.62 | 42.50 | 16.26 | 322 | 0.58 |

| Croatia | 1041 | 35.91 | 41.73 | 11.70 | 1835 | 63.30 | 42.32 | 11.84 | 23 | 0.79 | 44.26 | 13.75 | 2899 | 5.22 |

| Egypt | 24 | 14.55 | 37.38 | 14.18 | 141 | 85.45 | 39.66 | 11.82 | 0.00 | 165 | 0.30 | |||

| France | 64 | 24.33 | 38.98 | 14.70 | 197 | 74.90 | 37.89 | 15.53 | 2 | 0.76 | 27.50 | 10.61 | 263 | 0.47 |

| Georgia | 48 | 11.59 | 30.77 | 6.82 | 364 | 87.92 | 32.06 | 9.04 | 2 | 0.48 | 33.50 | 6.36 | 414 | 0.74 |

| Germany | 15 | 25.00 | 48.93 | 18.58 | 45 | 75.00 | 34.87 | 13.98 | 0.00 | 60 | 0.11 | |||

| Greece | 624 | 18.26 | 36.55 | 10.58 | 2772 | 81.10 | 34.00 | 9.87 | 22 | 0.64 | 29.59 | 6.68 | 3418 | 6.15 |

| Honduras | 74 | 33.48 | 28.19 | 7.17 | 147 | 66.52 | 32.05 | 11.09 | 0.00 | 221 | 0.40 | |||

| Hungary | 146 | 19.13 | 44.60 | 11.95 | 617 | 80.87 | 41.36 | 11.95 | 0.00 | 763 | 1.37 | |||

| India | 3044 | 61.01 | 33.51 | 8.94 | 1917 | 38.42 | 31.59 | 11.97 | 28 | 0.56 | 28.36 | 7.86 | 4989 | 8.97 |

| Indonesia | 909 | 27.68 | 33.64 | 12.06 | 2358 | 71.80 | 30.49 | 11.42 | 17 | 0.52 | 28.00 | 11.62 | 3284 | 5.91 |

| Israel | 28 | 19.44 | 48.79 | 18.24 | 116 | 80.56 | 38.97 | 13.56 | 0.00 | 144 | 0.26 | |||

| Italy | 257 | 26.22 | 43.10 | 16.17 | 717 | 73.16 | 41.22 | 14.17 | 6 | 0.61 | 42.17 | 21.14 | 980 | 1.76 |

| Japan | 182 | 70.00 | 45.31 | 11.61 | 78 | 30.00 | 41.71 | 11.10 | 0.00 | 260 | 0.47 | |||

| Kyrgyz Republic | 614 | 27.76 | 36.38 | 14.16 | 1561 | 70.57 | 38.87 | 14.58 | 37 | 1.67 | 33.57 | 12.60 | 2212 | 3.98 |

| Latvia | 1036 | 39.72 | 48.18 | 12.38 | 1570 | 60.20 | 45.26 | 14.64 | 2 | 0.08 | 48.00 | 18.38 | 2608 | 4.69 |

| Lithuania | 271 | 21.54 | 39.34 | 13.62 | 983 | 78.14 | 40.16 | 12.75 | 4 | 0.32 | 40.75 | 12.89 | 1258 | 2.26 |

| Malaysia | 311 | 32.29 | 41.95 | 12.08 | 578 | 60.02 | 39.24 | 11.71 | 74 | 7.68 | 39.03 | 12.66 | 963 | 1.73 |

| Mexico | 447 | 25.03 | 36.84 | 16.13 | 1332 | 74.58 | 38.18 | 14.74 | 7 | 0.39 | 22.86 | 4.78 | 1786 | 3.21 |

| Nigeria | 752 | 65.22 | 30.30 | 7.46 | 397 | 34.43 | 25.83 | 7.55 | 4 | 0.35 | 31.75 | 7.97 | 1153 | 2.07 |

| Pakistan | 575 | 28.24 | 25.46 | 6.35 | 1445 | 70.97 | 23.45 | 4.42 | 16 | 0.79 | 24.75 | 10.93 | 2036 | 3.66 |

| Peru | 56 | 36.13 | 43.80 | 15.80 | 99 | 63.87 | 38.72 | 14.03 | 0.00 | 155 | 0.28 | |||

| Poland | 286 | 18.58 | 33.46 | 11.54 | 1239 | 80.51 | 33.65 | 11.24 | 14 | 0.91 | 31.21 | 14.67 | 1539 | 2.77 |

| Portugal | 16 | 18.82 | 43.31 | 18.22 | 68 | 80.00 | 42.34 | 13.77 | 1 | 1.18 | 38.00 | 85 | 0.15 | |

| Romania | 293 | 20.22 | 47.54 | 14.45 | 1144 | 78.95 | 46.77 | 14.21 | 12 | 0.83 | 51.58 | 15.45 | 1449 | 2.61 |

| Russia | 3825 | 38.50 | 30.34 | 12.03 | 5847 | 58.85 | 31.74 | 12.25 | 264 | 2.66 | 27.64 | 10.87 | 9936 | 17.87 |

| Serbia | 152 | 25.08 | 39.16 | 11.94 | 453 | 74.75 | 41.84 | 11.77 | 1 | 0.17 | 58.00 | 606 | 1.09 | |

| Spain | 330 | 31.82 | 51.49 | 14.85 | 703 | 67.79 | 48.52 | 13.53 | 4 | 0.39 | 50.00 | 13.11 | 1037 | 1.87 |

| Turkey | 95 | 27.38 | 25.03 | 6.26 | 249 | 71.76 | 25.05 | 7.36 | 3 | 0.86 | 21.33 | 0.58 | 347 | 0.62 |

| Ukraine | 306 | 21.07 | 38.42 | 15.38 | 1132 | 77.96 | 39.09 | 13.13 | 14 | 0.96 | 35.93 | 17.88 | 1452 | 2.61 |

| UK | 55 | 34.38 | 43.53 | 11.12 | 105 | 65.63 | 44.56 | 11.95 | 0.00 | 160 | 0.29 | |||

| USA | 124 | 30.32 | 37.50 | 15.47 | 273 | 66.75 | 37.78 | 14.51 | 12 | 2.93 | 28.00 | 9.78 | 409 | 0.74 |

| TOTAL | 18,927 | 34.05 | 34.90 | 13.29 | 36,047 | 64.85 | 35.80 | 13.61 | 615 | 1.11 | 31.64 | 13.15 | 55,589 | 100.00 |

The study population was self-selected. It was not possible to apply post-stratification on the sample as it was done in a previous study (Fountoulakis et al., 2021), because this would mean that we would utilize a similar methodology across much different countries and the population data needed were not available for all.

2.3. Statistical analysis

-

•

Chi-square tests were used for the comparison of frequencies when categorical variables were present and for the post hoc analysis of the results a Bonferroni-corrected method of pair-wise comparisons was utilized (MacDonald and Gardner, 2016).

-

•

Factorial Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to test for the main effect as well as the interaction among grouping variables concerning continuous variable. The scheffe test was used as the post-hoc test.

-

•

Multiple forward stepwise linear regression analysis (MFSLRA) was performed to investigate which variables could function as predictors contribute to the development of others (e.g. depression).

2.4. Results

2.4.1. Demographics

The study sample included data from 40 countries (Table 1). In total responses were gathered from 55,589 participants, aged 35.45±13.51 years old; 36,047 females (64.84%; aged 35.80±13.61) and 18,927 males (34.05%; aged 34.90±13.29), while 615 declared ‘non-binary gender’ (1.11%; aged 31.64±13.15). One third of the study sample was living in the country's capital and an additional almost one fifth in a city of more than one million inhabitants. Half were married or living with someone while 10.41% were living alone. Half had no children at all and approximately 75% had bachelor's degree or higher. In terms of employment, 23.54% were civil servants, 37.06% were working in the private sector, 18.35% were college or university students while the rest were retired or were not working for a variety of reasons; of these 33.86% did not work during lockdowns. The detailed composition of the study sample in terms of country by gender by age are shown in web Table 1, while the composition in terms or residency, marital status, household size, children, education and occupation are shown in the webTables 2–7 of the appendix.

2.4.2. History of health

Moderate or bad somatic health was reported by 17.79% and presence of a chronic medical somatic condition was reported by 20.43%. Detailed results are shown in webTables 8 and 9. Being either relatives or caretakers of vulnerable persons was reported by 44.41% (web Table 10).

In terms of mental health history and self-harm, 7.85% had a prior history of an anxiety disorder, 12.57% of depression, 1.16% of Bipolar disorder, 0.97% of psychosis and 2.70% of other mental disorder. Any mental disorder history was present in 25.25%. At least once, 21.44% had hurt themselves in the past and 10.59% had attempted at least once in the past. The detailed rates by sex and country are shown in webTable 11.

2.4.3. Family

In terms of family status, 43.95% were married, 48.53% had at least one child and only 10.41% were living alone. The responses suggested an increased need for communication with family members in 38.08%, an increased need for emotional support in 26.22%, fewer conflicts in 34.81% and increased conflicts within families for 37.71%, an improvement of the quality of relationships in 23.95%, while in most cases (61.62%) there was a maintenance of basic daily routine (webTable 12). During lockdowns 33.86% did not work, while 48.43% expected their economic situation to worsen because of the COVID-19 outbreak (webTable 13).

2.4.4. Present mental health

Concerning mental health, 47.41% reported an increase in anxiety, and 40.28% reported an increase in depressive feelings. Suicidal thoughts were increased in 10.83%. Overall, current probable depression was present in 20.49% of females, 12.36% of males and 27.64% of those registered as ‘non-binary gender’, with an unweighted average 17.80% for the whole study sample. Additionally, distress was present in 17.41%, 15.17%, 23.09% and 16.71% respectively. In aggregate, one third of the study sample manifested significant distress or probable depression. Persons with history of mental disorders had higher rates of current depression (31.82% vs. 13.07%, chi-square test = 2520.61; df=1; p<0.0001) (webTables 14, 15, 18 and 19). The rates were identical, no mater whether the history concerned a psychotic or non-psychotic disorder. Of the 20.49% in females with depression half were new cases (without any past history of mental disorder) while this was true for two thirds of the 12.36% of males.

The mean scale scores were 43.58±13.08 for the STAI-S, 20.56±9.21 for the CES-D, and 93.27±152.81 for the Intention subscale of the RASS. The complete results by sex and country are shown in webTable 17.

From the total sample, 4.80% reported that they often thought much or very much about committing suicide if they had the chance. Males and females had similar rates (4.96% vs. 4.48%) but those self-identified as ‘non-binary gender’ had much higher rates (19.18%). In subjects with a history of psychotic disorder or self-harm/attempt the rate was 15.39% while in those with history of non-psychotic disorder it was 8.41%. In persons free of any mental disorder or self-harm/attempt history the rate was as low as 1.14%. This means that the RR for the manifestation of at least moderate suicidal thoughts was equal to 13.5 for psychotic history and 7.37 for non-psychotic history. In those identified as ‘non-binary gender’ sex, the RR was equal to 4.28.

2.4.5. Lifestyle changes

There were lifestyle changes concerning physical activity, exercise, appetite and eating, sex and sleep and the respective rates are shown in webTable 20. The chances were both towards an improvement and towards a deterioration. The ‘excess’ reported here corresponds to the difference between these rates of deterioration minus improvement. In summary, in 45.05% the overall physical activity has been reduced, approximately an excess of 14% reported an increased appetite and was eating more than before, an excess of 10% more were eating in an unhealthy way and 13.21% put more than 2 kgs of body weight. Internet and social media use were increased in 62.38% and 54.35% respectively but new habits emerged only in 22.11%. A decrease in smoking and alcohol use was reported (an excess of 20% more were smoking and drinking less) while an excess of 30% reported reduction in the use of illegal substances. The frequency of intercourse and satisfaction were inadequate for approximately an excess of 20%. In approximately 19.18% religious or spiritual inquires increased at least ‘much’.

2.4.6. Beliefs in conspiracy theories

On average at least half of cases accepted at least a moderate degree some non-bizarre conspiracy including the deliberate release of the virus as a bio-weapon to deliberately create a global crisis. In detail the responses by sex and country are shown in webTable 21.

2.4.7. Modeling of mental health changes during the pandemic

The presence of any mental health history acted as a risk factor for the development of current probable depression with all chi-square tests being significant at p < 0.001 (see webappendix part 3.2.1 in Statistical analysis). Interestingly a history of self-harm or suicidality emerged as a risk factor even for persons without reporting mental health history. In persons with only history of self-harm or suicidality, 23.44% developed probable depression. The combination of both self-harm and suicidal attempts history with specific mental health history revealed that subjects without any such history at all had the lowest rate or current depression (10.73%), while the presence of previous self-harm/attempts increased the risk in subjects with past anxiety (36.94%), depression (50.19%), Bipolar disorder (63.11%), psychoses (48.58%) and other mental disorder (41.23%). The highest relative risk (RR) was calculated for the combined presence of history of Bipolar disorder and self-harm/attempt (RR=5.88). All RR values are shown in Table 2 . After taking into consideration that the annual incidence of depression is 0.3% (Liu et al., 2020), the calculated risk because of the pandemic for the general population to develop depression is RR>40.

Table 2.

Relative Risk (RR) to develop depression vs. participants with no mental health history and no history of self-harm or suicidal acts.

| When alone |

When history of self-harm/attempt is also present |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| History | % | RR | % | RR |

| No previous history at all | 10.73 | 1.00 | 1.0 | |

| Any mental disorder | 31.81 | 2.96 | ||

| Anxiety | 25.93 | 2.42 | 36.94 | 3.44 |

| Depression | 35.31 | 3.29 | 50.19 | 4.68 |

| Bipolar disorder | 47.98 | 4.47 | 63.11 | 5.88 |

| Psychosis | 37.59 | 3.50 | 48.58 | 4.53 |

| Other | 23.61 | 2.20 | 41.23 | 3.44 |

| Only history of self-harm/attempt | 23.44 | 2.18 | ||

The presence of a chronic somatic condition acted as a significant but weak risk factor for the development of depression (Chi-square = 87.533.72, df = 2, p < 0.001; Bonferroni corrected Post-hoc tests suggested the two groups differed in the presence of depression (p < 0.001) but not distress (p > 0.05). In terms of rates, 20.78% of those with a chronic somatic condition manifested depression vs. 17.03% of those without (RR=1.22).

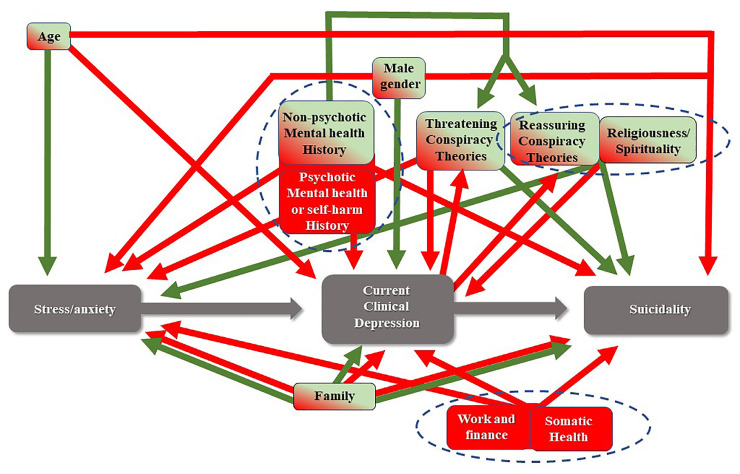

The results of the MFSLRA suggested that a significant number of variables acted either as risk or as protective factors (Table 3 , Fig. 2 ). These factors explained 16.4% of change in anxiety, 13.5% of change in depressive affect, 4.7% of change in suicidal thoughts and 23.9% of the development of distress or depression. The individual contribution of each predictor separately was very small (many b coefficients were very close to zero).

Table 3.

Results of four separate Multiple Forward Stepwise Linear Regression Analysis (MFSLRA) with change in anxiety (F21), change in depressive affect (G21), change in suicidal thoughts (O11) and the development of distress or depression as dependent variables. The predictors are shown in the left column.

|

Change in anxiety (F21)R²= 0.164; F(30,45,821)=301.42 p<<0.0001; SE of est: 0.819 |

Change in depressive affect (G21)R²= 0.135; F(25,45,826)=286.45 p<<0.0001; SE of est: 0.840 |

Development of distress or depressionR²= 0.239; F(31,45,816)=464.99 p<<0.0001; SE of est: 0.673 |

Change in suicidal thoughts (O11)R²= 0.047; F(31,45,820)=72.429 p<<0.0001; SE of est: 0.784 |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | T | p | b | SE | t | p | b | SE | t | p | b | SE | t | p | |

| Intercept | −0.75 | 0.03 | −24.60 | <0.0001 | −0.81 | 0.03 | −26.37 | <0.0001 | 0.81 | 0.02 | 32.30 | <0.0001 | 0.46 | 0.03 | 15.93 | <0.0001 |

| Demographics | ||||||||||||||||

| Sex (A1)- ‘non-binary gender’ was not included | 0.04 | 0.01 | 4.57 | <0.0001 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −2.03 | 0.0426 | −0.09 | 0.01 | −13.25 | <0.0001 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 3.79 | 0.0002 |

| Age (A2) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 6.91 | <0.0001 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −13.14 | <0.0001 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −7.87 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Number of persons in household (A5) | 0.01 | 0.00 | 3.98 | 0.0001 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 4.61 | <0.0001 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −4.66 | <0.0001 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −4.07 | <0.0001 |

| Education level (A7) | −0.04 | 0.00 | −8.37 | <0.0001 | −0.02 | 0.00 | −4.02 | 0.0001 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −2.34 | 0.0193 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 3.68 | 0.0002 |

| Work and finance | ||||||||||||||||

| Continue to work during lockdown (A11) | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.01 | 0.0447 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −2.95 | 0.0032 | ||||||||

| Change in economic situation (E7) | 0.10 | 0.00 | 28.56 | <0.0001 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 26.90 | <0.0001 | −0.03 | 0.00 | −9.93 | <0.0001 | −0.02 | 0.00 | −7.14 | <0.0001 |

| Health | ||||||||||||||||

| Condition of general health (B1) | 0.13 | 0.00 | 33.51 | <0.0001 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 28.83 | <0.0001 | −0.11 | 0.00 | −34.88 | <0.0001 | −0.04 | 0.00 | −11.26 | <0.0001 |

| Presence of a chronic medical condition (B2) | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.60 | 0.0093 | ||||||||||||

| Family/social | ||||||||||||||||

| Being a carer of a person belonging to a vulnerable group (B4) | −0.02 | 0.01 | −2.29 | 0.0220 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −2.16 | 0.0312 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 4.74 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Conflicts within family (E3) | −0.04 | 0.00 | −10.35 | <0.0001 | −0.06 | 0.00 | −13.24 | <0.0001 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 20.83 | <0.0001 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 13.71 | <0.0001 |

| Change in quality of relationships within family (E4) | 0.15 | 0.01 | 29.11 | <0.0001 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 31.80 | <0.0001 | −0.04 | 0.00 | −8.62 | <0.0001 | −0.08 | 0.01 | −15.42 | <0.0001 |

| Keeping a basic routine during lockdown (E5) | 0.11 | 0.00 | 25.54 | <0.0001 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 24.14 | <0.0001 | −0.11 | 0.00 | −29.75 | <0.0001 | −0.04 | 0.00 | −10.45 | <0.0001 |

| Changes in religiousness/spirituality (P1) | 0.01 | 0.00 | 2.76 | 0.0057 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 8.02 | <0.0001 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 13.01 | <0.0001 | −0.03 | 0.00 | −6.95 | <0.0001 |

| Mental health history | ||||||||||||||||

| History of anxiety (B5) | −0.29 | 0.06 | −4.69 | <0.0001 | −0.51 | 0.06 | −8.14 | <0.0001 | 1.79 | 0.05 | 35.24 | <0.0001 | 0.61 | 0.06 | 10.25 | <0.0001 |

| History of depression (B5) | −0.26 | 0.06 | −4.35 | <0.0001 | −0.49 | 0.06 | −7.99 | <0.0001 | 1.91 | 0.05 | 38.97 | <0.0001 | 0.58 | 0.06 | 10.20 | <0.0001 |

| History of Psychosis (B5) | −0.25 | 0.07 | −3.54 | 0.0004 | −0.36 | 0.07 | −4.96 | <0.0001 | 1.85 | 0.06 | 31.32 | <0.0001 | 0.51 | 0.07 | 7.48 | <0.0001 |

| History of Bipolar disorder (B5) | −0.27 | 0.07 | −3.94 | 0.0001 | −0.47 | 0.07 | −6.82 | <0.0001 | 1.94 | 0.06 | 34.85 | <0.0001 | 0.62 | 0.06 | 9.52 | <0.0001 |

| History of other mental disorder (B5) | −0.29 | 0.06 | −4.56 | <0.0001 | −0.48 | 0.07 | −7.31 | <0.0001 | 1.75 | 0.05 | 33.34 | <0.0001 | 0.61 | 0.06 | 10.01 | <0.0001 |

| History only self-harm/attempt (combination of B5, O12 and O13) | −0.02 | 0.01 | −3.02 | 0.0025 | −0.04 | 0.01 | −6.36 | <0.0001 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 31.49 | <0.0001 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 9.25 | <0.0001 |

| The effect of the pandemic | ||||||||||||||||

| Fears of getting COVID-19 (C1) | −0.09 | 0.00 | −20.77 | <0.0001 | −0.06 | 0.00 | −12.45 | <0.0001 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 16.01 | <0.0001 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 4.41 | <0.0001 |

| Fears that a member of the family will get COVID-19 and die (C3) | −0.06 | 0.00 | −16.35 | <0.0001 | −0.04 | 0.00 | −10.06 | <0.0001 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 17.27 | <0.0001 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −4.08 | <0.0001 |

| Time spent outside of house during lockdown (D1) | 0.02 | 0.00 | 7.55 | <0.0001 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 4.76 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Currently locked up in the house (D2) | −0.02 | 0.00 | −5.65 | <0.0001 | −0.04 | 0.00 | −8.44 | <0.0001 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 7.64 | <0.0001 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 4.11 | <0.0001 |

| Satisfaction by availability of information (D4) | 0.05 | 0.00 | 12.27 | <0.0001 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 9.86 | <0.0001 | −0.02 | 0.00 | −7.12 | <0.0001 | −0.05 | 0.00 | −13.78 | <0.0001 |

| Beliefs in conspiracy theories | ||||||||||||||||

| The vaccine was ready before the virus broke out and they conceal it (J1) | 0.02 | 0.00 | 5.55 | <0.0001 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 5.49 | <0.0001 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 5.47 | <0.0001 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −3.46 | 0.0005 |

| COVID-19 was created in a laboratory as a biochemical weapon (J2) | −0.01 | 0.00 | −2.17 | 0.0300 | −0.02 | 0.00 | −3.69 | 0.0002 | ||||||||

| COVID-19 is the result of 5 G technology antenna (J3) | −0.01 | 0.00 | −2.87 | 0.0041 | −0.03 | 0.00 | −5.16 | <0.0001 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 7.75 | <0.0001 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 2.74 | 0.0062 |

| COVID-19 appeared accidentally from human contact with animals (J4) | −0.02 | 0.00 | −7.21 | <0.0001 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 7.82 | <0.0001 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −3.71 | 0.0002 | ||||

| COVID-19 has much lower mortality rate but there is terror-inducing propaganda (J5) | 0.01 | 0.00 | 3.02 | 0.0026 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 3.47 | 0.0005 | −0.02 | 0.00 | −6.22 | <0.0001 | ||||

| COVID-19 is a creation of the world's powerful leaders to create a global economic crisis (J6) | −0.01 | 0.00 | −2.24 | 0.0251 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −2.35 | 0.0186 | ||||||||

| COVID-19 is a sign of divine power to destroy our planet (J7) | 0.02 | 0.00 | 5.20 | <0.0001 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 5.48 | <0.0001 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 4.71 | <0.0001 | ||||

Fig. 2.

The developed multiple vulnerabilities model representing the mechanism through which the COVID-19 outbreak in combination a great number of factors could lead to depression through stress, and eventually to suicidality. A number of variables act as risk factors (red) or as protective factors (green), while some of them change direction of action depending on the phase (green/red). Three core clusters emerge (delineated with the doted lines).

If we consider a more or less linear continuum from fear to anxiety to depressive emotions to probable depression and eventually to suicidality, the model which can be derived suggests there is a core of variables (Fig. 2) which exert a stable either adverse or protective effect throughout the course of the development of mental state.

Factorial ANOVA was significant for sex (Wilks=0.989, F = 39.85, df=16, error df=111,000, p<0.0001) and type of work (Wilks=0.990, F = 7.22, df=80, error df=352,000, p<0.0001) as well as for their interaction (Wilks=0.990, F = 3.40, df=160, error df=415,000, p<0.0001) concerning the scores of STAI-S, CES-D and RASS. The Scheffe post-hoc tests (at p<0.05) revealed that most groups defined by sex and occupation differed from each other in a complex and difficult to explain matrix.

Conspiracy theories manifest a complex behavior with some of them exerting a protective effect at certain phases (Fig. 2). The mean scores of responses to questions pertaining to different conspiracy beliefs by history of any mental disorder and current probable depression are shown in Table 4 . Factorial ANOVA suggested that sex, history of any mental disorder and current probable depression as well as some but not all their interaction (after correction for multiple testing) were significant factors concerning the belief in conspiracy theories (Table 5 ). The results of post-hoc tests are shown in webTable 25. They suggest that females were significantly more likely to believe in conspiracy theories than males. This is also true for those with current probable depression. Interestingly, those with history of non-psychotic disorder (anxiety, depression, other) were less likely to believe in conspiracy theories in comparison to those without, while the opposite was true concerning psychotic history (bipolar disorder, psychosis) as well as history of self-harm and suicidal attempts. These findings were consistent across disorders and conspiracy theories.

Table 4.

Means of responses (from −2 to +2) to all conspiracy theories by current clinical depresson and history of any mental disorder.

|

Reassuring conspiracy theories |

Threatening conspiracy theories |

No believing in conspiracy theories |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Clinical depression | History Of any Mental dis |

J1 |

J5 |

J7 |

J2 |

J3 |

J6 |

J4 |

|||||||

| mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | ||

| No | Yes | 0.82 | 1.13 | 1.37 | 1.30 | 0.49 | 0.96 | 1.16 | 1.24 | 0.46 | 0.91 | 1.12 | 1.26 | 1.88 | 1.24 |

| No | No | 0.97 | 1.15 | 1.48 | 1.28 | 0.62 | 1.03 | 1.35 | 1.25 | 0.59 | 0.98 | 1.30 | 1.27 | 1.69 | 1.21 |

| Yes | Yes | 1.09 | 1.28 | 1.52 | 1.33 | 0.68 | 1.12 | 1.40 | 1.34 | 0.65 | 1.09 | 1.33 | 1.33 | 1.90 | 1.25 |

| Yes | No | 1.23 | 1.24 | 1.59 | 1.28 | 0.96 | 1.23 | 1.57 | 1.29 | 0.89 | 1.17 | 1.53 | 1.31 | 1.78 | 1.22 |

| All Grps | 0.98 | 1.17 | 1.48 | 1.29 | 0.64 | 1.05 | 1.34 | 1.26 | 0.60 | 1.01 | 1.29 | 1.28 | 1.75 | 1.22 | |

Table 5.

Factorial ANOVA results, with sex, history of any mental disorder and current probable depression as factors. All factors are significant as well as some their interaction (after correction for multiple testing) concerning the belief in conspiracy theories.

| Effect | Wilks' | F | effect df | Error df | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.988 | 91.7 | 7 | 54,956 | <0.0001 |

| History of any mental disorder | 0.994 | 44.2 | 7 | 54,956 | <0.0001 |

| Probable depression (currently) | 0.985 | 122.3 | 7 | 54,956 | <0.0001 |

| Sex by History of any mental disorder | 1 | 2.2 | 7 | 54,956 | 0.030 |

| Sex by Probable depression (currently) | 0.998 | 16.4 | 7 | 54,956 | <0.0001 |

| Probable depression (currently) by History of any mental disorder | 0.999 | 8.7 | 7 | 54,956 | <0.0001 |

| Sex by Probable depression (currently) by History of any mental disorder | 1 | 2.6 | 7 | 54,956 | 0.010 |

The investigation of the interaction of current depression with history of non-psychotic mental disorder suggested that current depression acted as a risk factor and history acted as a protective. On the contrary there was no interaction between current depression and history of psychosis or self-harm/attempt.

3. Discussion

This large international study in convenience sample of 55,589 participants from 40 countries detected probable depression in 20.49% of females, 12.36% of males and 27.64% of those registered as ‘non-binary gender’ (average 17.80%). Distress was present in 17.41%, 15.17%, 23.09% and 16.71% respectively. A significant percentage reported a deterioration in mental state, family dynamics and everyday lifestyle. Persons with history of mental disorders had higher rates of current probable depression (31.82% vs. 13.07%) and there was no difference on the basis of whether the history concerned a psychotic or a non-psychotic disorder. Believing in conspiracy theories was widespread with at least half of cases accepting at least to a moderate degree some non-bizarre conspiracy. History of any mental health disorder or self-harm or suicidality was a risk factor for the development of current probable depression. Person without any such history had the lowest rate or current depression (10.73%), while the highest rate was for the coexistence of history of Bipolar disorder and self-harm/attempts (63.11%; RR=5.88). The rate of probable depression was 20.78% of those with a chronic somatic condition vs. 17.03% of those without (RR=1.22). The RR for the manifestation of at least moderate suicidal thoughts was equal to 13.5 for psychotic history and 7.37 for non-psychotic history. In those identified as ‘non-binary gender’ sex, the RR was equal to 4.28. For those without any mental health history, the rate of suicidal thoughts was exactly what would be expected from the general population (Fountoulakis et al., 2012).

The model developed suggested that a significant number of variables acted either as risk or as protective factors, explaining 23.9% of the development of distress or probable depression, but their individual contribution was very small. Conspiracy theories manifested a complex behavior with some of them exerting a protective effect at certain phases. Females were significantly more likely to believe in conspiracy theories and also this was true for those with current probable depression. Those with history of non-psychotic disorder (anxiety, depression, other) were less likely to believe in conspiracy theories, while the opposite was true for psychotic history (bipolar disorder, psychosis) as well as history of self-harm and suicidal attempts. These findings were consistent across disorders and theories. Current probable depression acted as a risk factor and past history acted as a protective for the development of such beliefs. On the contrary there was no interaction between current depression and history of psychosis or self-harm/attempt.

The overall levels of probable depression were lower than the rates reported in the literature, probably because of the stringent criteria of the algorithm in the current study. Other studies reported that more than two-thirds of the population experienced at least severe distress (Busch et al., 2021; Dominguez-Salas et al., 2020; Gualano et al., 2020; Knolle et al., 2021; Ozdin and Bayrak Ozdin, 2020b; Petzold et al., 2020; Verma and Mishra, 2020), a rate which is double in comparison to our findings. On the other hand other studies showed similar results (Cenat et al., 2021; Daly et al., 2021; Lei et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Prati, 2021; Wang et al., 2020a), and also concerning the role of self-determined sex (Duarte and Pereira, 2021; Fu et al., 2020; Garcia-Fernandez et al., 2021; Gualano et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020; Solomou and Constantinidou, 2020). High levels of suicidality have been reported previously (Caballero-Dominguez et al., 2020). Furthermore, our findings are in perfect accord with a recently published meta-analysis (Cenat et al., 2021). The large heterogeneity among countries probably reflects different phases of the pandemic in each country during the data collection. Rates of depression and mental health deterioration in general are probably higher in those that actually suffered from COVID-19 (Deng et al., 2021).

An important observation is that while the rate of probable depression was much higher in persons with a history of a mental disorder (31.82% vs. 13.07%) the proportion of depressed persons without such a history is much higher than expected, taking under consideration that the annual incidence of depression is 0.3% (Liu et al., 2020). This might mean that the pandemic posed a RR>40 on the general population to develop depression.

The multivariate analysis of the data allowed the current paper to propose a staged model concerning the effect of the pandemic on mental health (Figure 2). This model assumes that stress and anxiety develop first, then depression follows and eventually suicidality appears. These constitute distinct stages, and progress from earlier to later stages is not mandatory. It occurs only in a minority of the population. However, it is unlikely that a later stage appears without the previous emergence of an earlier stage.

According to the model proposed, with the onset of the pandemic, its psychological impact and the development of severe anxiety and distress were determined by several sociodemographic and interpersonal variables including age, fears specific to the pandemic, the quality of relationships within family, keeping a basic daily routine, change in economic situation, history of any mental disorder and being afraid that him/herself or a family member will get COVID-19 and die. Similar findings concerning the effects of these factors has been reported in the literature (Elbogen et al., 2021; Elhai et al., 2021; Gambin et al., 2021; Garre-Olmo et al., 2021; Huang and Zhao, 2020a, Huang and Zhao, 2020b; Li et al., 2020; Ozdin and Bayrak Ozdin, 2020b; Rossi et al., 2021; Solomou and Constantinidou, 2020; Wang et al., 2020a), but until now their detailed contribution had not been identified and no comprehensive model had been developed.

As the stressful condition persisted and anxiety developed into distress and dysphoric depressive-like states, greater age emerged as a protective factor. Interestingly at the next stage, when probable depression emerges, greater age may become a risk factor, while religious/spirituality exerts a mostly protective effect. This is in accord with an interpretation of burning out of the ‘based-on-reason and experience’ psychological coping resources, and as a result despair due to prolonged stress appears. When this happens, ‘coping mechanisms not based on reason’ may take over.

At pandemic onset we might not had imagined the important role and the impact of conspiracy theories, which are largely social media driven. They are currently widely accepted as being important since the literature strongly supports their relationship with anxiety and depression (Chen et al., 2020; De Coninck et al., 2021). What is interesting is that the results of the current study suggest that the COVID-19 related conspiracy theories could be classified as being either ‘threatening’ or ‘reassuring’ and these two groups exert different effects at different phases and periods. At the early phase, ‘threatening’ conspiracy theories cause anxiety and distress while the ‘reassuring’, which include an element of denial or religiousness, exert a protective effect and act as a coping-like mechanism. However, all of them act as risk factors for the development of probable depression, which implies that the coping function of some of them might backfire if initially unsuccessful. Interestingly, all of them seem to be protective factors against the development of suicidality (except for religious content), probably by gaining the role of a coping mechanism which, however, might reflect different underlying processes.

Current probable depression and past history of mental disorders are both critical factors related to believing in conspiracy theories. Our results could mean that the critical factor which increases belief is the presence of current probable depression, while the past history acts at a second level. As correlation does not imply causation, conspiracy theories could be either the cause of depression, a copying mechanism against depression or a marker of maladaptive psychological patterns of cognitive appraisal. After taking into consideration the complete model, and especially the relationship to past mental health history, the authors propose that the beliefs in conspiracy theories are a copying mechanism against stress. The finding of the relationship between current depression and believing in conspiracies is in accord with the literature (De Coninck et al., 2021; Freyler et al., 2019; Tomljenovic et al., 2020), but the finding of the differential effect of non-psychotic vs. psychotic history is difficult to explain, mainly concerning the protective effect of non-psychotic history. One explanation could be found in the theory concerning ‘Depressive Realism’ (Alloy et al., 1981; Alloy and Abramson, 1979, 1988; Beck et al., 1987; Lobitz and Post, 1979; Nelson and Craighead, 1977) which suggests that depressive persons are more able than others to realistically interpret the world, however this higher ability leads to pessimism. Previous reports on the role of temperament support such an interpretation (Moccia et al., 2020)

The restriction of time outside the house because of the lockdown is clearly a risk factor, and it interacts with history of mental disorder for the deterioration of mental state. This is in accord with the literature (Di Blasi et al., 2021; Rossi et al., 2021). At the most extreme end, when the emergence of suicidal thinking is possible, the family environment and family responsibilities and care act either as risk or protective factors, depending on their quality, while religiosity/spirituality and all beliefs in conspiracy theories act as protective factors, except for one which includes religious content. These results are in accord with the reports in the literature (Arslan and Yildirim, 2021; Huang and Zhao, 2020a, Huang and Zhao, 2020b; Jovancevic and Milicevic, 2020; Li et al., 2020; Ozdin and Bayrak Ozdin, 2020a; Wang et al., 2020a).

The high rates of believing in conspiracy theories are in accord with findings from various countries (Ahmed et al., 2020; Leibovitz et al., 2021; Salali and Uysal, 2020; Uscinski et al., 2020) and are a worrying manifestation. Conspiracy beliefs – especially those regarding science, medicine, and health-related topics – are widespread (Oliver and Wood, 2014), are widely distributed in the social media (Ahmed et al., 2020; Banerjee and Meena, 2021) and they challenge the capacity of the average person to distill and assess the content (Desta and Mulugeta, 2020; Duplaga, 2020). They exert a well-documented adverse effect on health behaviors, especially vaccination (Allington et al., 2020, 2021; Bertin et al., 2020; Biddlestone et al., 2020; Bogart et al., 2010; Freeman et al., 2020; Gu et al., 2021; Jolley and Douglas, 2014; Lazarevic et al., 2021; Marinthe et al., 2020; Romer and Jamieson, 2020; Salali and Uysal, 2020; Sallam et al., 2020; Soveri et al., 2021; Teovanovic et al., 2020). There seems to be some relationship of believing in bizarre conspiracy theories and psychotic tendencies or history of psychotic disorders (Jolley and Paterson, 2020).

A difficult to answer question is how many of the cases detected by questionnaires and sophisticated algorithms correspond to real probable depression. The underlying neurobiology is opaque and maybe much diagnosed depression might simply be an extreme form of a normal adjustment reaction (He et al., 2021). However there is no better way to psychometrically achieve higher validity and the algorithm we utilized is the best available method. The impressive increase in new cases of depression which was found in our sample, is in accord with the literature (Robillard et al., 2021). Half of females with depression were new cases while this was true for two thirds of depressed males. However a large part of depressions emerged from a previous mental health history and this suggests that almost beyond doubt true probable depression at least doubled and that maybe relapses expected to occur in the next 15–20 years occurred earlier.

Concerning those without a previous history of mental disorder, it is expected that much of the adverse effects on mental health will rapidly attenuate with the lifting of lockdown restrictions and the end of the pandemic (Daly and Robinson, 2021) but enduring effects will impact some vulnerable populations. So far studies investigating the long-term outcome and the long-term impact of the pandemic on mental health display equivocal findings (Bendau et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020b). Especially sociability and the sense of belonging could be important factors determining mental health and health-related behaviors (Biddlestone et al., 2020), and these factors seem to correspond to specific vulnerabilities seen especially in western cultures.

4. Conclusion

The current paper reports higher than expected rates of probable depression, distress and suicidal thoughts among the general population during the pandemic, with a high prevalence of beliefs in conspiracy theories. For the development of depression, general health status, previous mental health history, self-harm and suicidal attempts, family responsibility, economic change, and age acted as risk factors while keeping daily routine, religiousness/spirituality and belief in conspiracy theories were acting mostly as protective factors. These findings, although they should be closely monitored in a longitudinal way, support previous suggestions by other authors concerning the need for a proactive intervention to protect mental health of the general population but more specifically of vulnerable groups (Fiorillo and Gorwood, 2020; Sani et al., 2020)

5. Strengths and limitations

The strengths of the current paper include the large number of persons who filled the questionnaire and the large bulk of information obtained, as well as the detailed way of post-stratification of the study sample.

The major limitation was that the data were obtained anonymously online through self-selection of the responders. Additionally, the assessment included only the cross-sectional application of self-report scales, although the advanced algorithm used for the diagnosis of probable depression corrected the problem to a certain degree. However, what is included under the umbrella of ‘probable depression’ in the stressful times of the pandemic remains a matter of debate. Also, the lack of baseline data concerning the mental health of a similar study sample before the pandemic is also a problem.

Funding

None.

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally to the paper.

KNF and DS conceived and designed the study. The other authors participated formulating the final protocol, designing and supervising the data collection and creating the final dataset. KNF and DS did the data analysis and wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors participated in interpreting the data and developing further stages and the final version of the paper.

Conflict of Interest

None pertaining to the current paper.

Acknowledgement

None

References

- Ahmed W., Vidal-Alaball J., Downing J., Lopez Segui F. COVID-19 and the 5G Conspiracy theory: social network analysis of twitter data. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22:e19458. doi: 10.2196/19458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allington D., Duffy B., Wessely S., Dhavan N., Rubin J. Health-protective behaviour, social media usage and conspiracy belief during the COVID-19 public health emergency. Psychol. Med. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1017/S003329172000224X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allington D., McAndrew S., Moxham-Hall V., Duffy B. Coronavirus conspiracy suspicions, general vaccine attitudes, trust and coronavirus information source as predictors of vaccine hesitancy among UK residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Med. 2021:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721001434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy, L., Abramson, L., Viscusi, D.J.J.o.P., Psychology, S., 1981. Induced mood and the illusion of control. 41, 1129–1140.

- Alloy L.B., Abramson L.Y. Judgment of contingency in depressed and nondepressed students: sadder but wiser? J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1979;108:441–485. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.108.4.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy L.B., Abramson L.Y. The Guilford Press; New York, NY, US: 1988. Depressive Realism: Four Theoretical Perspectives, Cognitive processes in Depression; pp. 223–265. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan G., Yildirim M. Meaning-based coping and spirituality during the COVID-19 pandemic: mediating effects on subjective well-being. Front. Psychol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmundson G.J.G., Taylor S. Garbage in, garbage out: the tenuous state of research on PTSD in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and infodemic. J. Anxiety Disord. 2021;78 doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee D., Meena K.S. COVID-19 as an "Infodemic" in public health: critical role of the social media. Front. Public Health. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.610623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Beck A.T., Brown G., Steer R.A., Eidelson J.I., Riskind J.H. Differentiating anxiety and depression: a test of the cognitive content-specificity hypothesis. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1987;96:179–183. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.96.3.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendau A., Plag J., Kunas S., Wyka S., Strohle A., Petzold M.B. Longitudinal changes in anxiety and psychological distress, and associated risk and protective factors during the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. Brain Behav. 2021;11:e01964. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertin P., Nera K., Delouvee S. Conspiracy beliefs, rejection of vaccination, and support for hydroxychloroquine: a conceptual replication-extension in the COVID-19 pandemic context. Front. Psychol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.565128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biddlestone M., Green R., Douglas K.M. Cultural orientation, power, belief in conspiracy theories, and intentions to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2020;59:663–673. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart L.M., Wagner G., Galvan F.H., Banks D. Conspiracy beliefs about HIV are related to antiretroviral treatment nonadherence among african american men with HIV. J. Acquir. Immune. Defic Syndr. 2010;53:648–655. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c57dbc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch I.M., Moretti F., Mazzi M., Wu A.W., Rimondini M. What we have learned from two decades of epidemics and pandemics: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychological burden of frontline healthcare workers. Psychother. Psychosom. 2021;90:178–190. doi: 10.1159/000513733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero-Dominguez C.C., Jimenez-Villamizar M.P., Campo-Arias A. Suicide risk during the lockdown due to coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Colombia. Death Stud. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2020.1784312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenat J.M., Blais-Rochette C., Kokou-Kpolou C.K., Noorishad P.G., Mukunzi J.N., McIntee S.E., Dalexis R.D., Goulet M.A., Labelle P.R. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Zhang S.X., Jahanshahi A.A., Alvarez-Risco A., Dai H., Li J., Ibarra V.G. Belief in a COVID-19 conspiracy theory as a predictor of mental health and well-being of health care workers in ecuador: cross-sectional survey study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6:e20737. doi: 10.2196/20737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtet P., Olie E. Suicide in the COVID-19 pandemic: what we learnt and great expectations. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;50:118–120. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly M., Robinson E. Anxiety reported by US adults in 2019 and during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic: population-based evidence from two nationally representative samples. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;286:296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly M., Sutin A.R., Robinson E. Depression reported by US adults in 2017-2018 and March and April 2020. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;278:131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Coninck D., Frissen T., Matthijs K., d'Haenens L., Lits G., Champagne-Poirier O., Carignan M.E., David M.D., Pignard-Cheynel N., Salerno S., Genereux M. Beliefs in conspiracy theories and misinformation about COVID-19: comparative perspectives on the role of anxiety, depression and exposure to and trust in information sources. Front. Psychol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng J., Zhou F., Hou W., Silver Z., Wong C.Y., Chang O., Huang E., Zuo Q.K. The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances in COVID-19 patients: a meta-analysis. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2021;1486:90–111. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desta T.T., Mulugeta T. Living with COVID-19-triggered pseudoscience and conspiracies. Int. J. Public Health. 2020;65:713–714. doi: 10.1007/s00038-020-01412-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Blasi M., Gullo S., Mancinelli E., Freda M.F., Esposito G., Gelo O.C.G., Lagetto G., Giordano C., Mazzeschi C., Pazzagli C., Salcuni S., Lo Coco G. Psychological distress associated with the COVID-19 lockdown: a two-wave network analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;284:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Salas S., Gomez-Salgado J., Andres-Villas M., Diaz-Milanes D., Romero-Martin M., Ruiz-Frutos C. Psycho-emotional approach to the psychological distress related to the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: a cross-sectional observational study. Healthcare (Basel) 2020;8 doi: 10.3390/healthcare8030190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte M., Pereira H. The Impact of COVID-19 on depressive symptoms through the lens of sexual orientation. Brain Sci. 2021:11. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11040523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duplaga M. The determinants of conspiracy beliefs related to the COVID-19 pandemic in a nationally representative sample of internet users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17217818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbogen E.B., Lanier M., Blakey S.M., Wagner H.R., Tsai J. Suicidal ideation and thoughts of self-harm during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of COVID-19-related stress, social isolation, and financial strain. Depress Anxiety. 2021 doi: 10.1002/da.23162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhai J.D., Yang H., McKay D., Asmundson G.J.G., Montag C. Modeling anxiety and fear of COVID-19 using machine learning in a sample of Chinese adults: associations with psychopathology, sociodemographic, and exposure variables. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2021;34:130–144. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2021.1878158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt D., Steptoe A., Bu F. Trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms during enforced isolation due to COVID-19 in England: a longitudinal observational study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:141–149. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30482-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorillo A., Gorwood P. The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and implications for clinical practice. Eur Psychiatry. 2020;63:e32. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa R., Gilbert S., Fabian M.O. COVID-19 and subjective well-being: separating the effects of lockdowns from the pandemic. Lancet. 2021 (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Fountoulakis K., Iacovides A., Kleanthous S., Samolis S., Kaprinis S.G., Sitzoglou K., St Kaprinis G., Bech P. Reliability, validity and psychometric properties of the Greek translation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) Scale. BMC Psychiatry. 2001;1:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fountoulakis K.N., Apostolidou M.K., Atsiova M.B., Filippidou A.K., Florou A.K., Gousiou D.S., Katsara A.R., Mantzari S.N., Padouva-Markoulaki M., Papatriantafyllou E.I., Sacharidi P.I., Tonia A.I., Tsagalidou E.G., Zymara V.P., Prezerakos P.E., Koupidis S.A., Fountoulakis N.K., Chrousos G.P. Self-reported changes in anxiety, depression and suicidality during the COVID-19 lockdown in Greece. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;279:624–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fountoulakis K.N., Pantoula E., Siamouli M., Moutou K., Gonda X., Rihmer Z., Iacovides A., Akiskal H. Development of the risk assessment suicidality scale (RASS): a population-based study. J Affect. Disord. 2012;138:449–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman D., Loe B.S., Chadwick A., Vaccari C., Waite F., Rosebrock L., Jenner L., Petit A., Lewandowsky S., Vanderslott S., Innocenti S., Larkin M., Giubilini A., Yu L.M., McShane H., Pollard A.J., Lambe S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: the Oxford coronavirus explanations, attitudes, and narratives survey (Oceans) II. Psychol. Med. 2020:1–15. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720005188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyler A., Simor P., Szemerszky R., Szabolcs Z., Koteles F. Modern health worries in patients with affective disorders. A pilot study. Ideggyogy. Sz. 2019;72:337–341. doi: 10.18071/isz.72.0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu W., Wang C., Zou L., Guo Y., Lu Z., Yan S., Mao J. Psychological health, sleep quality, and coping styles to stress facing the COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Transl. Psychiatry. 2020;10:225. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-00913-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullana M.A., Hidalgo-Mazzei D., Vieta E., Radua J. Coping behaviors associated with decreased anxiety and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;275:80–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullana M.A., Littarelli S.A. COVID-19, anxiety, and anxiety-related disorders. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;51:87–89. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambin M., Sekowski M., Wozniak-Prus M., Wnuk A., Oleksy T., Cudo A., Hansen K., Huflejt-Lukasik M., Kubicka K., Lys A.E., Gorgol J., Holas P., Kmita G., Lojek E., Maison D. Generalized anxiety and depressive symptoms in various age groups during the COVID-19 lockdown in Poland. Specific predictors and differences in symptoms severity. Compr. Psychiatry. 2021;105 doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Fernandez L., Romero-Ferreiro V., Padilla S., David Lopez-Roldan P., Monzo-Garcia M., Rodriguez-Jimenez R. Gender differences in emotional response to the COVID-19 outbreak in Spain. Brain Behav. 2021;11:e01934. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garre-Olmo J., Turro-Garriga O., Marti-Lluch R., Zacarias-Pons L., Alves-Cabratosa L., Serrano-Sarbosa D., Vilalta-Franch J., Ramos R., Girona Healthy Region Study, G. Changes in lifestyle resulting from confinement due to COVID-19 and depressive symptomatology: a cross-sectional a population-based study. Compr. Psychiatry. 2021;104 doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonda X., Tarazi F.I. Well-being, resilience and post-traumatic growth in the era of Covid-19 pandemic. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.08.266. S0924-0977X(0921)00742-00742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu F., Wu Y., Hu X., Guo J., Yang X., Zhao X. The role of conspiracy theories in the spread of COVID-19 across the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18 doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gualano M.R., Lo Moro G., Voglino G., Bert F., Siliquini R. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on mental health and sleep disturbances in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17134779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L., Wei D., Yang F., Zhang J., Cheng W., Feng J., Yang W., Zhuang K., Chen Q., Ren Z., Li Y., Wang X., Mao Y., Chen Z., Liao M., Cui H., Li C., He Q., Lei X., Feng T., Chen H., Xie P., Rolls E.T., Su L., Li L., Qiu J. Functional connectome prediction of anxiety related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2021 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20070979. appiajp202020070979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Zhao N. Chinese mental health burden during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020;51 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Zhao N. Mental health burden for the public affected by the COVID-19 outbreak in China: who will be the high-risk group? Psychol. Health Med. 2020:1–12. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1754438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolley D., Douglas K.M. The effects of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories on vaccination intentions. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e89177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolley D., Paterson J.L. Pylons ablaze: examining the role of 5G COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and support for violence. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2020;59:628–640. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovancevic A., Milicevic N. Optimism-pessimism, conspiracy theories and general trust as factors contributing to COVID-19 related behavior - A cross-cultural study. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2020;167 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knolle F., Ronan L., Murray G.K. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a comparison between Germany and the UK. BMC Psychol. 2021;9:60. doi: 10.1186/s40359-021-00565-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarevic L.B., Puric D., Teovanovic P., Lukic P., Zupan Z., Knezevic G. What drives us to be (ir)responsible for our health during the COVID-19 pandemic? The role of personality, thinking styles, and conspiracy mentality. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2021;176 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei L., Huang X., Zhang S., Yang J., Yang L., Xu M. Comparison of prevalence and associated factors of anxiety and depression among people affected by versus people unaffected by quarantine during the COVID-19 epidemic in Southwestern China. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020;26 doi: 10.12659/MSM.924609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibovitz T., Shamblaw A.L., Rumas R., Best M.W. COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs: relations with anxiety, quality of life, and schemas. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2021;175 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Yang Z., Qiu H., Wang Y., Jian L., Ji J., Li K. Anxiety and depression among general population in China at the peak of the COVID-19 epidemic. World Psychiatry. 2020;19:249–250. doi: 10.1002/wps.20758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., He H., Yang J., Feng X., Zhao F., Lyu J. Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: findings from the Global Burden of Disease study. J. Psychiatr Res. 2020;126:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobitz W.C., Post R.D. Parameters of self-reinforcement and depression. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1979;88:33–41. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.88.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald P.L., Gardner R.C. Type I error rate comparisons of post hoc procedures for I j Chi-Square tables. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2016;60:735–754. [Google Scholar]

- Marinthe G., Brown G., Delouvee S., Jolley D. Looking out for myself: exploring the relationship between conspiracy mentality, perceived personal risk, and COVID-19 prevention measures. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020;25:957–980. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moccia L., Janiri D., Pepe M., Dattoli L., Molinaro M., De Martin V., Chieffo D., Janiri L., Fiorillo A., Sani G., Di Nicola, M. Affective temperament, attachment style, and the psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak: an early report on the Italian general population. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;87:75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortier, P., Vilagut, G., Ferrer, M., Serra, C., Molina, J.D., Lopez-Fresnena, N., Puig, T., Pelayo-Teran, J.M., Pijoan, J.I., Emparanza, J.I., Espuga, M., Plana, N., Gonzalez-Pinto, A., Orti-Lucas, R.M., de Salazar, A.M., Rius, C., Aragones, E., Del Cura-Gonzalez, I., Aragon-Pena, A., Campos, M., Parellada, M., Perez-Zapata, A., Forjaz, M.J., Sanz, F., Haro, J.M., Vieta, E., Perez-Sola, V., Kessler, R.C., Bruffaerts, R., Alonso, J., Group, M.W., 2021. Thirty-day suicidal thoughts and behaviors among hospital workers during the first wave of the Spain COVID-19 outbreak. Depress Anxiety38, 528–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nelson R.E., Craighead W.E. Selective recall of positive and negative feedback, self-control behaviors, and depression. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1977;86:379–388. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.86.4.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver J.E., Wood T. Medical conspiracy theories and health behaviors in the United States. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014;174:817–818. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozdin S., Bayrak Ozdin S. Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkish society: the importance of gender. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020927051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozdin S., Bayrak Ozdin S. Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkish society: the importance of gender. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2020;66:504–511. doi: 10.1177/0020764020927051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petzold M.B., Bendau A., Plag J., Pyrkosch L., Mascarell Maricic L., Betzler F., Rogoll J., Grosse J., Strohle A. Risk, resilience, psychological distress, and anxiety at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. Brain Behav. 2020:e01745. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompili M. Can we expect a rise in suicide rates after the Covid-19 pandemic outbreak? Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;52:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prati G. Mental health and its psychosocial predictors during national quarantine in Italy against the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Anxiety Stress Coping. 2021;34:145–156. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2020.1861253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine N., Hetherington E., McArthur B.A., McDonald S., Edwards S., Tough S., Madigan S. Maternal depressive and anxiety symptoms before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: a longitudinal analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:405–415. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00074-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recchi E., Ferragina E., Helmeid E., Pauly S., Safi M., Sauger N., Schradie J. The “Eye of the Hurricane” paradox: an unexpected and unequal rise of well-being during the COVID-19 lockdown in France. Res. Soc. Stratif Mobil. 2020;68 doi: 10.1016/j.rssm.2020.100508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X., Huang W., Pan H., Huang T., Wang X., Ma Y. Mental health during the COVID-19 outbreak in China: a meta-analysis. Psychiatr Q. 2020:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s11126-020-09796-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robillard R., Daros A.R., Phillips J.L., Porteous M., Saad M., Pennestri M.H., Kendzerska T., Edwards J.D., Solomonova E., Bhatla R., Godbout R., Kaminsky Z., Boafo A., Quilty L.C. Emerging new psychiatric symptoms and the worsening of pre-existing mental disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic: a Canadian multisite study: nouveaux symptomes psychiatriques emergents et deterioration des troubles mentaux preexistants durant la pandemie de la COVID-19: une etude canadienne multisite. Can. J. Psychiatry. 2021 doi: 10.1177/0706743720986786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romer D., Jamieson K.H. Conspiracy theories as barriers to controlling the spread of COVID-19 in the U.S. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020;263 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi R., Jannini T.B., Socci V., Pacitti F., Lorenzo G.D. Stressful life events and resilience during the COVID-19 lockdown measures in italy: association with mental health outcomes and age. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.635832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saladino V., Algeri D., Auriemma V. The psychological and social impact of COVID-19. New Perspect. Well-Being. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salali G.D., Uysal M.S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is associated with beliefs on the origin of the novel coronavirus in the UK and Turkey. Psychol. Med. 2020:1–3. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720004067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salari N., Hosseinian-Far A., Jalali R., Vaisi-Raygani A., Rasoulpoor S., Mohammadi M., Rasoulpoor S., Khaledi-Paveh B. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Health. 2020;16:57. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallam M., Dababseh D., Yaseen A., Al-Haidar A., Taim D., Eid H., Ababneh N.A., Bakri F.G., Mahafzah A. COVID-19 misinformation: mere harmless delusions or much more? A knowledge and attitude cross-sectional study among the general public residing in Jordan. PLoS ONE. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sani G., Janiri D., Di Nicola M., Janiri L., Ferretti S., Chieffo D. Mental health during and after the COVID-19 emergency in Italy. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020;74:372. doi: 10.1111/pcn.13004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevlin M., Butter S., McBride O., Murphy J., Gibson-Miller J., Hartman T.K., Levita L., Mason L., Martinez A.P., McKay R., Stocks T.V.A., Bennett K., Hyland P., Bentall R.P. Refuting the myth of a 'tsunami' of mental ill-health in populations affected by COVID-19: evidence that response to the pandemic is heterogeneous, not homogeneous. Psychol. Med. 2021:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721001665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L., Lu Z.A., Que J.Y., Huang X.L., Liu L., Ran M.S., Gong Y.M., Yuan K., Yan W., Sun Y.K., Shi J., Bao Y.P., Lu L. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with mental health symptoms among the general population in china during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14053. -e2014053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomou I., Constantinidou F. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety and depression symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic and compliance with precautionary measures: age and sex matter. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17144924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soveri A., Karlsson L.C., Antfolk J., Lindfelt M., Lewandowsky S. Unwillingness to engage in behaviors that protect against COVID-19: the role of conspiracy beliefs, trust, and endorsement of complementary and alternative medicine. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:684. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10643-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C.D. Mind Garden; Redwood City California: 2005. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory For Adults. [Google Scholar]

- Taquet M., Geddes J.R., Husain M., Luciano S., Harrison P.J. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:416–427. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00084-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teovanovic P., Lukic P., Zupan Z., Lazic A., Ninkovic M., Zezelj I. Irrational beliefs differentially predict adherence to guidelines and pseudoscientific practices during the COVID-19 pandemic. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/acp.3770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomljenovic H., Bubic A., Erceg N. It just doesn't feel right - the relevance of emotions and intuition for parental vaccine conspiracy beliefs and vaccination uptake. Psychol. Health. 2020;35:538–554. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2019.1673894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uscinski J., Enders A., Klofstad C., Seelig M., Funchion J., Everett C., Wuchty S., Premaratne K., Murthi M. Why do people believe COVID-19 conspiracy theories? The Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review. 2020;1 doi: 10.37016/mr-2020-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Velden P.G., Contino C., Das M., van Loon P., Bosmans M.W.G. Anxiety and depression symptoms, and lack of emotional support among the general population before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. A prospective national study on prevalence and risk factors. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;277:540–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma S., Mishra A. Depression, anxiety, and stress and socio-demographic correlates among general Indian public during COVID-19. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2020;66:756–762. doi: 10.1177/0020764020934508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinkers C.H., van Amelsvoort T., Bisson J.I., Branchi I., Cryan J.F., Domschke K., Howes O.D., Manchia M., Pinto L., de Quervain D., Schmidt M.V., van der Wee N.J.A. Stress resilience during the coronavirus pandemic. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;35:12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., Ho C.S., Ho R.C. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., McIntyre R.S., Choo F.N., Tran B., Ho R., Sharma V.K., Ho C. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;87:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]