Abstract

Gic2p is a Cdc42p effector which functions during cytoskeletal organization at bud emergence and in response to pheromones, but it is not understood how Gic2p interacts with the actin cytoskeleton. Here we show that Gic2p displayed multiple genetic interactions with Bni1p, Bud6p (Aip3p), and Spa2p, suggesting that Gic2p may regulate their function in vivo. In support of this idea, Gic2p cofractionated with Bud6p and Spa2p and interacted with Bud6p by coimmunoprecipitation and two-hybrid analysis. Importantly, localization of Bni1p and Bud6p to the incipient bud site was dependent on active Cdc42p and the Gic proteins but did not require an intact actin cytoskeleton. We identified a conserved domain in Gic2p which was necessary for its polarization function but dispensable for binding to Cdc42p-GTP and its localization to the site of polarization. Expression of a mutant Gic2p harboring a single-amino-acid substitution in this domain (Gic2pW23A) interfered with polarized growth in a dominant-negative manner and prevented recruitment of Bni1p and Bud6p to the incipient bud site. We propose that at bud emergence, Gic2p functions as an adaptor which may link activated Cdc42p to components involved in actin organization and polarized growth, including Bni1p, Spa2p, and Bud6p.

The development of both unicellular and multicellular organisms requires cells to respond to intracellular and extracellular cues which direct growth and division. These signals regulate the actin cytoskeleton, which is required for maintenance of cell shape and polarity, cell motility, intracellular trafficking, cytokinesis, and phagocytosis (16). Members of the Rho family of GTPases, including Rho, Rac, and Cdc42, have emerged as key regulators that control cell adhesion, the establishment of cell polarity, and the organization and dynamics of the actin cytoskeleton. These biological responses are mediated through their interaction with multiple target proteins, but little is known about how they regulate the actin cytoskeleton.

The budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae undergoes polarized cell growth at several stages of its life cycle (4, 27, 42, 43). During mating, pheromones activate a signal transduction cascade leading to polarization and projection formation (29). During vegetative growth, cells in early G1 grow isotropically and insert new cell wall material all over their surface until they reach a critical size, at which time activation of the G1 cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdc28p-Clnp) initiates cytoskeletal polarization and bud emergence (34). Polarized cell growth is a complex process that requires the polarized organisation of the actin cytoskeleton and the coordinated function of many polarity proteins and signal transduction cascades. The actin cytoskeleton appears as two distinct structures: cortical actin patches are concentrated at sites of polarized growth, and actin cables run parallel to the polarity axis (7). Cortical actin patches, although highly mobile, are thought to be filamentous actin wrapped around invaginations of the plasma membrane (37). A polarized actin cytoskeleton directs secretory vesicles containing cell wall and plasma membrane components to growth sites, resulting in polarized growth.

Activation of Cdc42p by its exchange factor Cdc24p is required to organize the actin cytoskeleton towards the incipient bud site or towards the pheromone-secreting partner during mating. Cytoskeletal polarization also requires Bem1p, a protein with two SH3 domains which is thought to function as an adaptor for Cdc42p and Cdc24p (41). In the absence of Cdc42p function, cells fail to grow in a polarized manner and instead increase in size isotropically (1). Several effectors of Cdc42p have been identified, including the PAK-like kinases Ste20p, Cla4p, and Skm1p and Gic1p and Gic2p (23). None of these proteins alone can account for the effect of Cdc42p on polarized growth, suggesting that these targets cooperate to polarize the actin cytoskeleton. The interaction occurs through a characteristic CRIB motif (Cdc42-Rac-interactive binding), which is found in many Cdc42p effectors and has been conserved from yeasts to humans (9). Cla4p, Ste20p, Gic1p, and Gic2p localize to sites of polarized growth in a Cdc42p-dependent manner (8, 10, 18, 30, 40); this localization requires a functional CRIB domain, suggesting that Cdc42p targets these proteins to the site of polarization. Cells lacking both STE20 and CLA4 are defective for actin nucleation (11), most likely because they fail to phosphorylate Myo3p and Myo5p (31). Cells deleted for both Gic proteins exhibit severe polarization defects at bud emergence and in response to pheromones (8, 10), but their sequences do not provide any clues to their function.

A group of proteins including Bni1p, Bud6p, Pea2p, and Spa2p are involved in a wide variety of responses which require dynamic organization of the actin cytoskeleton (43, 46). Cells deleted for any of these proteins are viable but show defects at bud emergence and in response to pheromones, pseudohyphal growth, and correct bud site selection in diploid cells (52). In addition, they contribute to anchor the mitotic spindle to the cell cortex (32, 36). Because these components localize to the incipient bud site in the G1 phase of the cell cycle, they may act early in establishing and/or maintaining cell polarity. Bni1p, Bud6p, and Spa2p interact with each other in two-hybrid and coimmunoprecipitation assays and cofractionate on glycerol gradients as a large complex termed the 12S polarisome (46). However, it remains to be determined whether they indeed function together in a single multisubunit complex in vivo. Bni1p is a member of the evolutionarily conserved formin family (51), which participates in a wide range of actin-mediated processes affecting cell polarity and shape in many organisms. Bni1p interacts through distinct domains with the actin-associated proteins profilin and Bud6p (12, 19). Profilin is a known regulator of actin polymerization; it is able to sequester actin monomers and stimulates exchange of the nucleotide bound to actin (45, 49). Profilin also binds to proline-rich sequences of human VASP and murine Mena, which both promote actin assembly. Thus, Bni1p, Bud6p, Pea2p, and Spa2p are involved in targeting, maintaining, and remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton during dynamic growth periods at various phases of polarized growth. However, it is not understood how they are regulated by different signals and how they localize to sites of polarized growth. Bni1p has been shown to interact with multiple Rho-GTPases (51), which, together with Spa2p, may be involved in localizing or maintaining Bni1p at sites of polarization (13).

In this study we have investigated the role of the Gic proteins in polarized morphogenesis. We found that GIC2 exhibits multiple genetic interactions with BNI1, SPA2, and BUD6. Interestingly, Cdc42p and the Gic proteins are required to localize Bni1p and Bud6p to the incipient bud site in the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Gic2p cofractionates with Bud6p and Spa2p and interacts with Bud6p by coimmunoprecipitation and two-hybrid assays. Taken together, our results suggest that the Gic proteins may function as adaptors which link activated Cdc42p to components involved in assembly of the actin cytoskeleton at sites of polarized growth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and genetic experiments.

The yeast strains are described in Table 1. The genotypes of the yeast strains are as follows: W303, ade2-1 trp1-1 can1-100 leu2-3,112 his3-11,15 ura3 GAL+ psi+ ssd1-d2; S288C, ade2-101 ura3-52 lys2-801 trp1-Δ1 his3Δ200 leu2-Δ; and A364a, trp1-289 leu2-3,112 his3-11,15 ura3-52 GAL+, unless noted otherwise. Standard yeast growth conditions and genetic manipulations were used as described (15). Yeast transformations were performed by the lithium acetate procedure (20). Strains deleted for GIC2 marked with LEU2 were constructed using plasmid pMJ83 digested with HindIII and NotI. The unmarked deletion of GIC2 was obtained after plating the gic2::HISG-URA3 deletion strain (21) on plates containing 5-fluoroorotic acid. Pheromone response and mating assays were performed as described (50).

TABLE 1.

Strains

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Background | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| MJ494 | bnr1::URA3 | W303 | C. Boone |

| MJ492 | spa2::URA3 | W303 | C. Boone |

| MJ493 | bud6::URA3 | W303 | C. Boone |

| MJ491 | bni1::URA3 | W303 | C. Boone |

| MJ83 | gic2::LEU2 | W303 | M. Jaquenoud |

| MJ567 | gic2::LEU2 spa2::URA3 | W303 | This study |

| MJ560 | gic2::LEU2 bud6::URA3 | W303 | This study |

| MJ804 | gic2::Δbni1::URA3 | W303 | This study |

| MJ595 | gic2::LEU2 bud6::URA3 cdc34-2 | W303 | This study |

| MJ592 | gic2::LEU2 bud6::URA3 cdc4-1 | W303 | This study |

| MJ261 | gic2::LEU2 cdc4-1 | W303 | M. Jaquenoud |

| MJ391 | cdc42-1 | W303 | I. Herskowitz |

| MOSY0124 | cdc42-27 | W303 | D. Lew |

| YMP483 | cdc24-5 | W303 | J. Chenevert |

| MJ717 | gic1::HISG gic2::LEU2 | W303 | This study |

| MJ398 | gic1::URA3 gic2::HISG URA3 | W303 | M. Jaquenoud |

| MJ275 | his3::GAL CDC42G12VHIS3 | W303 | M. Peter |

| MJ631 | his3::GAL GIC2W23AHIS3 gic2::LEU2 | W303 | This study |

| MJ756 | sec18-1 | S288C | R. Hagenauer-Tsapis |

| YMG258 | cln1::HISG cln2Δ cln3::leu2::HISG YipLac204 MET CLN2 | W303 | M.-P. Gulli |

DNA manipulations.

Plasmids and oligonucleotides are described in Table 2 (38, 47). Standard procedures were used for recombinant DNA manipulations (2, 44). PCRs were performed with the Expand polymerase kit as recommended by the manufacturer (Boehringer Mannheim). Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Genset (Paris, France). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the method developed earlier (28), and the correct sequence of the mutants was confirmed by sequencing.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids and oligonucleotides

| Plasmid or oligonucleotide | Relevant characterics or sequence (5′→3′) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| MJ172 | GIC2 TRP1 CEN | M. Jaquenoud |

| MJ62 | GAL GIC2 TRP1 CEN | M. Jaquenoud |

| MJ720 | GIC2 GFP TRP1 CEN | This study |

| MJ383 | GAL GIC2 GFP TRP1 CEN | This study |

| MJ708 | GIC21–208GFP TRP1 CEN | This study |

| MJ384 | GAL GIC2crib−GFP TRP1 CEN | This study |

| MJ411 | GAL GIC2W23AGFP TRP1 CEN | This study |

| MJ402 | GIC2W23ATRP1 CEN | This study |

| MJ403 | GIC2Y34ATRP1 CEN | This study |

| MJ404 | GIC2P73ATRP1 CEN | This study |

| MJ486 | GAL GIC2W23A/crib−GFP TRP1 CEN | This study |

| P1874 | GAL HA BUD6 URA3 CEN | C. Boone |

| P2226 | ADH BNI1 GFP URA3 CEN | C. Boone |

| ACB 462 | ADH BEM1 GFP TRP1 CEN | A.-C. Butty |

| pDAb204 | ACT1 BUD6 GFP URA3 CEN | D. Amberg |

| pDAb259 | ACT1 BUD61–409GFP URA3 CEN | D. Amberg |

| MJ508 | BD BUD6 pEG202 | C. Boone |

| pHJ22 | BD BUD61–409pEG202 | D. Amberg |

| MJ509 | BD PEA2 pEG202 | C. Boone |

| MJ368 | BD CDC42C188SpEG202 | C. Boone |

| NP156 | GAL RHO1Q68LLEU2 CEN | N. Perrinjaquet |

| MJ42 | AD GIC2 pJG4-5 | M. Jaquenoud |

| MJ177 | AD GIC2crib−pJG4-5 | M. Jaquenoud |

| MJ478 | AD GIC2W23ApJG4-5 | This study |

| MJ791 | AD GIC2W23A/crib−pJG4-5 | This study |

| PYS50 | ADH CDC24 GFP TRP1 CEN | Y. Shimada |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| OTP356 | GCATTGCGGCCGCTTATAATTTTGGCGTTCAGCAAGCGCGCGG | |

| OTP409 | ACTGGAATTCAATATGACTAGTGCAAGTATTACC | |

| OTP491 | GGTTTGCAGGAATTCGAGCTGG | |

| OTP499 | ATGGAATTCACTCGAGAGAGGAGGCAACTCAA | |

| OTP500 | GCTGAAAAACTCGCAGGCCTGCAGGCCCAGC | |

| OTP502 | AACATTGAGTTGGCGCCACTTTCACCAAATTC | |

| OTP725 | CGAACGGAATTCTGATAGTCTTGATGTCTTAT |

Antibodies and Western blots.

Standard procedures were used for yeast cell extract preparation and immunoblotting (8, 17). Polyclonal anti-Gic2p and anti-Spa2p antibodies have been described previously (8, 48); polyclonal antibodies against green fluorescent protein (GFP) were kindly provided by P. Silver. Monoclonal antibodies specific for actin or the hemagglutinin (HA) epitope (HA11) were purchased from Boehringer Mannheim or Berkeley antibody company, respectively, and used as recommended by the manufacturer. 9E10 and monoclonal anti-GFP antibodies were obtained from the Swiss Institute for Experimental Cancer Research antibody facility.

Coimmunoprecipitation experiments.

Wild-type cells (K699) expressing either HA-Bud6p and Gic2p-GFP or GFP-Bud6p and HA-Gic2p were grown in selective medium to mid-log phase at 30°C, pelleted, and lysed in lysis buffer as described previously (6). Then 8 mg of soluble proteins were incubated for 2 h at 4°C with HA11- or B23-GFP antibodies; immunocomplexes were collected with 40 μl of protein G-Sepharose (Pharmacia) and washed six times with ice-cold lysis buffer. The pellet was transferred to a new tube to prevent unspecific binding and resuspended in 70 μl of sample buffer. Precipitated proteins were immunoblotted with HA11 or GFP antibodies to control for the presence of HA-Bud6p and GFP-Bud6p, respectively, and polyclonal antibodies against GFP or monoclonal HA11 antibodies to detect the presence of coimmunoprecipitated Gic2p-GFP or HA-Gic2p, respectively.

Gel filtration.

Wild-type cells (K699) harboring plasmids encoding HA-BUD6 (P1874) and GIC2 (MJ62) were grown at 30°C to mid-log phase in selective medium containing raffinose (2% final concentration), and expression of Gic2p and HA-Bud6p was induced for 3 h by the addition of galactose (2% final concentration). The cells were pelleted and lysed as described previously (6). The extract was first centrifuged at 4°C for 10 minutes at 10,000 × g followed by 10 min at 100,000 × g in a TFT80.2 rotor (S100). Approximately 800 μg of the soluble S100 supernatant was loaded on a Superose 6PC 3.2/30 column compatible with the SMART system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotechnology GMBH). Aliquots (50 μl) were collected, concentrated, and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and immunoblotting. Standard molecular size markers included chymotrypsin (25 kDa), bovine serum albumin (67 kDa), catalase (239 kDa), and tyroglobuline (669 kDa) were run separately to control the fractionation.

Determination of the half-lives of Gic2p and two-hybrid assays.

The half-lives of wild-type and mutant forms of Gic2p were determined as described previously (21). Two-hybrid assays were carried out as described (8). Two-hybrid plasmids for PEA2, BNI1, and full-length BUD6 were kindly provided by C. Boone (12); the two-hybrid plasmid expressing Bud6p1–409 was obtained from D. Amberg (22).

Cell cycle synchronization and experiments with latrunculin A.

G0-G1 release experiments with latrunculin A (LatA) were carried out essentially as described by Ayscough and coworkers (3). Briefly, cells were plated on selective medium, grown for at least 2 days at 30°C (25°C for temperature-sensitive strains), and resuspended in 10 ml of 50% YPD containing 1 M sorbitol. Cells were centrifuged for 2 min at 1,200 rpm without braking to enrich small cells in the supernatant. Small cells were then collected by centrifugation and resuspended in selective medium (time zero) warmed to the appropriate temperature (30°C for wild-type cells unless noted otherwise, and 37°C for temperature-sensitive strains). Where indicated LatA (final concentration, 20 μg/ml; stock solution, 10 μg/μl in dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) or, as a control, DMSO was added, and the cells were observed at different time points by GFP and phase-contrast microscopy. Staining with rhodamine-phalloidin controlled depolarization of the actin cytoskeleton by LatA.

G1 arrest of cln1,2,3Δ pMETCLN2 (YMG258) cells was achieved by repressing CLN2 for 3 h in selective medium supplemented with 2 mM methionine (21). After two quick washes, cells were divided: one half was released by inducing Cln2p expression in medium lacking methionine, while the other half was held in arrest by resuspending cells in medium containing 2 mM methionine. The cells were observed after 3 h by GFP and phase-contrast microscopy. Where indicated, LatA (200 μM final concentration in DMSO) or, as a control, DMSO was added.

Microscopy and morphological examination.

Yeast actin was visualized with rhodamine-phalloidin (Molecular Probes, Inc., Leiden, The Netherlands). Briefly, cells were fixed with formaldehyde (3.7% final concentration) for 60 min, washed, stained for 20 min on ice with rhodamine-phalloidin (diluted 1:5 in methanol), washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline, and viewed on a Zeiss Axiophot fluorescence microscope. At least 200 cells were counted for the morphological analysis. Proteins tagged with GFP were visualized on a Zeiss Axiophot fluorescence microscope using a Chroma GFPII filter (excitation, 440 to 470 nm), photographed with a Photometrics CCD camera, and analyzed with Photoshop 4.0 software (Adobe). Where indicated, photographs are shown as overlays of phase contrast and fluorescence images.

RESULTS

Genetic interactions between GIC2 and BNI1, BUD6, and SPA2.

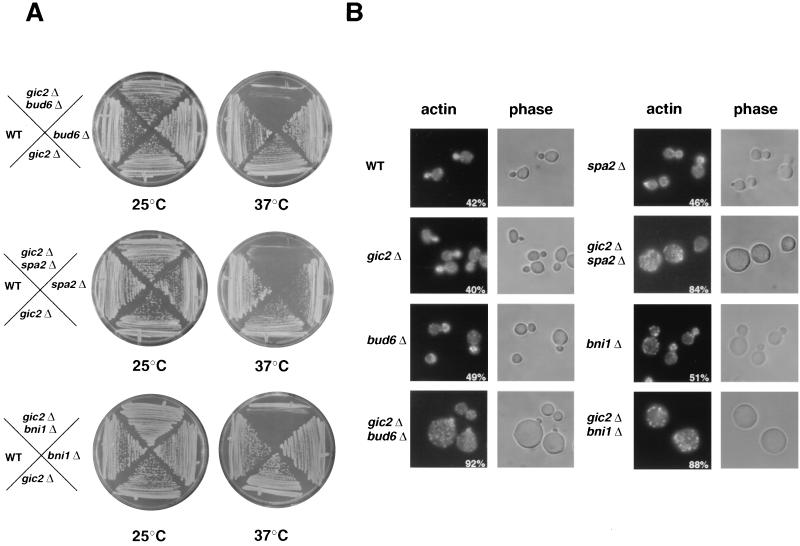

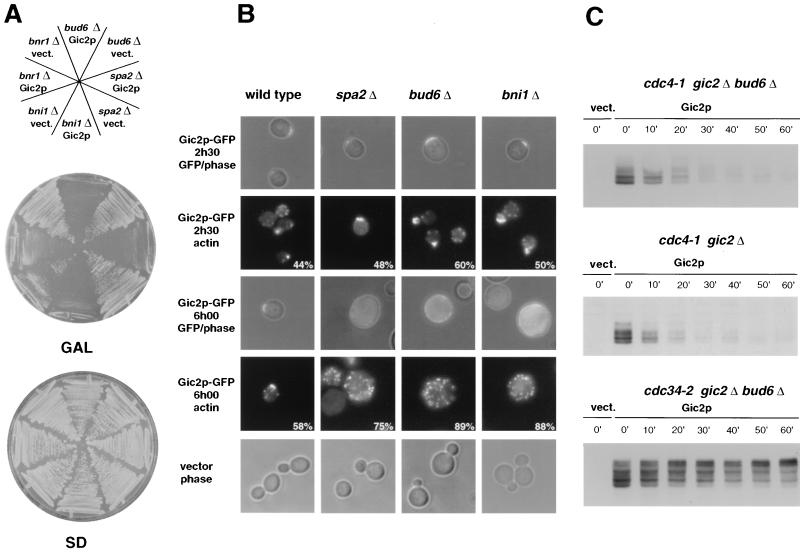

To address the function of Gic2p in cytoskeletal polarization, we examined genetic interactions between GIC2 and known components involved in the organization of the actin cytoskeleton. Interestingly, gic2Δ cells deleted for BNI1, BUD6, or SPA2 exhibited a synthetic phenotype, and the double mutants were unable to grow at 37°C, while all single mutants grew efficiently (Fig. 1A). Conversely, overexpression of Gic2p was lethal in bni1Δ, spa2Δ, or bud6Δ cells, whereas bnr1Δ cells grew slowly (Fig. 2A). Thus, cells defective for the function of either Bni1p, Bud6p, or Spa2p are sensitive to altered Gic2p levels. Morphological examination showed that gic2Δ bni1Δ, gic2Δ spa2Δ, and gic2Δ bud6Δ double mutants (Fig. 1B), as well as bni1Δ, bud6Δ, or spa2Δ cells overexpressing Gic2p (Fig. 2B), accumulated as large unbudded cells with a perturbed actin cytoskeleton, suggesting that the cells fail to polarize growth towards a single site on the cortex. Most of the cells contained a single nucleus with a G2 DNA content (data not shown), indicating that the nuclear cycle was arrested by the morphogenesis checkpoint after DNA replication (33). Overexpressed Gic2p-GFP was initially able to localize correctly to the incipient bud site in spa2Δ, bud6Δ, and spa2Δ cells (Fig. 2B), but the cells failed to maintain Gic2p at these sites in the absence of bud emergence. The half-life of Gic2p in cdc4-1 bud6Δ cells was comparable to its half-life in cdc4-1 cells (Fig. 2C), excluding the possibility that overexpression of Gic2p is toxic because of an involvement of Bud6p in its ubiquitin-dependent degradation. When shifted to the restrictive temperature, cdc4-1 cells arrest prior to DNA replication in a cell cycle phase where Gic2p is very unstable (half-life of less than 10 min) (21). Consistent with these findings, Bud6p was not required for hyperphosphorylation of Gic2p (Fig. 2C, bottom panel), which is a prerequisite to target Gic2p for ubiquitination by SCFGrr1 (21). Thus, Bud6p is not required to degrade Gic2p, implying that overexpression of Gic2p prevents bud emergence in these mutants by a novel mechanism.

FIG. 1.

GIC2 displays synthetic interactions with BUD6, SPA2, and BNI1. Cells lacking GIC2 (MJ83) were crossed to cells deleted for BUD6 (MJ493), SPA2 (MJ492), or BNI1 (MJ491), and the resulting haploid single or double mutants were analyzed in rich medium (YPD) at either 25°C (left plates) or 37°C (right plates). Note that gic2Δ cells lacking BNI1, BUD6, or SPA2 are unable to form colonies at 37°C (panel A), and arrest as large unbudded cells with an unpolarized actin cytoskeleton (panel B). The numbers indicate the percentage of cells which accumulated with an unpolarized actin cytoskeleton 3 h after the temperature shift to 37°C. At least 200 cells were counted for each strain. Actin staining was performed with rhodamine-phalloidin (left panels); phase-contrast images of the same cells are shown (right panels). All panels are printed at the same magnification. WT, wild type.

FIG. 2.

Overexpression of Gic2p is lethal in cells lacking BUD6, SPA2, and BNI1. (A) Cells with the indicated genotypes (upper panel) were transformed with a control vector (vect.) or a plasmid overexpressing Gic2p from the inducible GAL promoter (Gic2p) and tested for their ability to grow at 30°C on selective medium containing galactose (GAL; Gic2p expressed) or glucose (SD; Gic2p not expressed). Note that overexpression of Gic2p is toxic in strains defective for BUD6, SPA2, or BNI1. (B) The phenotype of cells transformed with an empty vector (bottom row) or a plasmid overexpressing Gic2p-GFP (upper rows) from the GAL promoter was analyzed 2.5 h (upper two rows) or 6 h (middle two rows) after induction of Gic2p-GFP by the addition of galactose. The pictures show overlays of GFP fluorescence with phase contrast (GFP/phase) or actin staining using rhodamine-phalloidin (actin). The numbers indicate the percentage of cells which accumulated with an unpolarized actin cytoskeleton; at least 200 cells were counted for each transformant. The following cells are shown (from left to right): wild-type (K699); spa2Δ (MJ492); bud6Δ (MJ493); and bni1Δ (MJ491). (C) Degradation of Gic2p is not dependent on Bud6p. Cells harboring a plasmid coding for GIC2 from the inducible GAL promoter were grown in raffinose, and expression was induced by the addition of galactose for 3 h at 37°C. Glucose was then added to repress the GAL promoter, and samples were taken every 10 min as indicated and immunoblotted for the presence of Gic2p. The following strains were analyzed: cdc4-1 gic2Δ bud6Δ (MJ592); cdc4-1 gic2Δ (MJ261); and cdc34-2 gic2Δ bud6Δ (MJ595). Note that Bud6p is not required for either phosphorylation or degradation of Gic2p.

Localization of Gic2p, Bni1p, and Bud6p at bud emergence required Cdc42p but was mostly independent of actin and an intact secretion pathway.

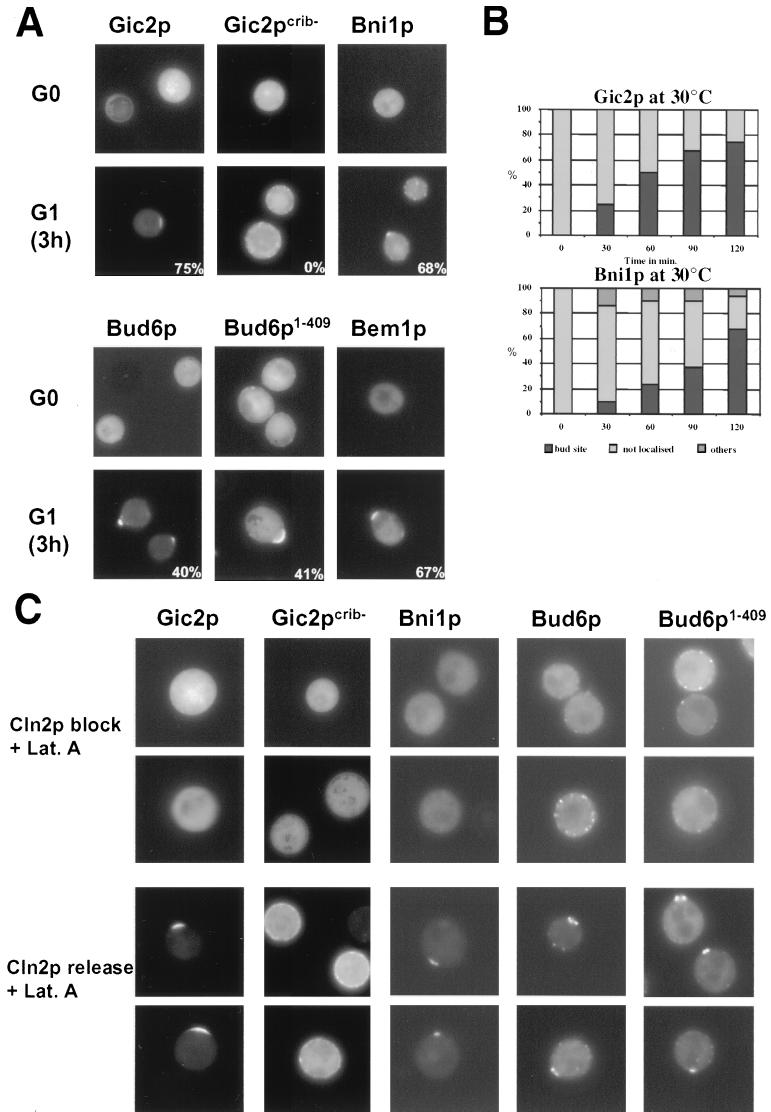

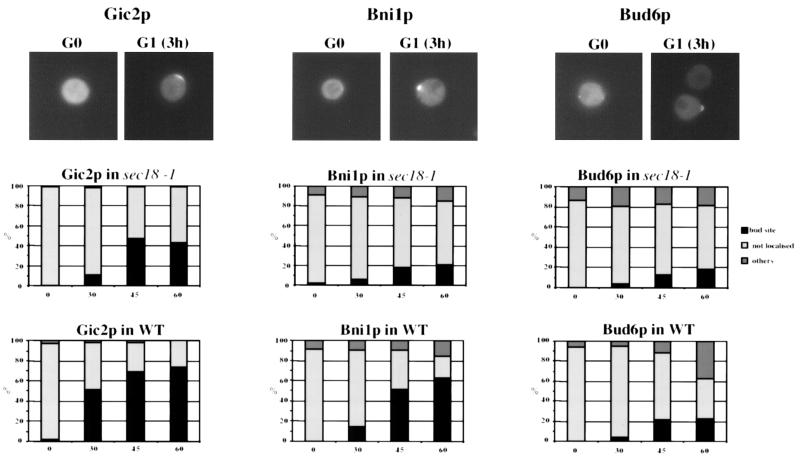

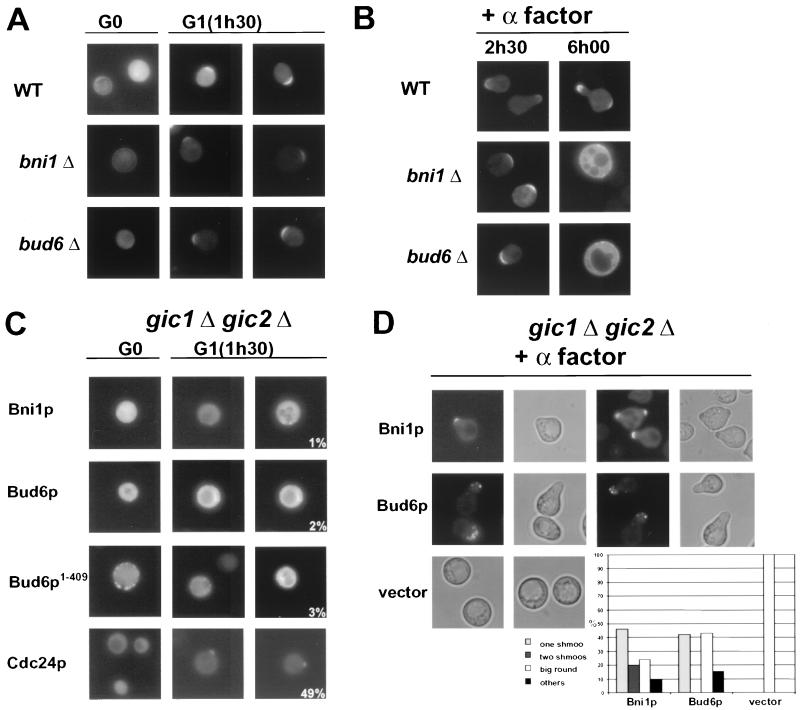

To determine whether localization of Gic2p, Bni1p, or Bud6p to the incipient bud site requires an intact actin cytoskeleton, we adapted a protocol established by Ayscough and coworkers (3). Briefly, cells were released into the cell cycle from a block in G0 in the presence and absence of the actin-depolymerizing drug LatA and the localization of Gic2p, Bni1p, and Bud6p was followed by GFP fluorescence microscopy. As shown in Fig. 3A, approximately 70% of wild-type cells were able to localize Gic2p, Bni1p, and Bem1p to the presumptive bud site in the presence of LatA. Interestingly, Gic2p localized slightly but reproducibly before Bni1p (Fig. 3B), indicating that Gic2p may precede Bni1p at the cell cortex. Full-length Bud6p and its amino-terminal domain (Bud6p1–409) were also able to localize asymmetrically, but the efficiency was reduced in the presence of LatA (40% of the cells correctly localized Bud6p to the incipient bud site in the presence of LatA) (3). Supporting these results, Bni1p, Bud6p, Bud6p1–409, and Gic2p were distributed throughout the cytoplasm in cells arrested at start by depletion of the G1 cyclins (Fig. 3C, upper panels; Cln2p block). However, these proteins efficiently localized to the incipient bud site after reexpression of Cln2p, even if bud emergence was prevented by the addition of LatA (Fig. 3C, lower panel; Cln2p release). Asymmetric localization of Gic2p required an intact CRIB domain (Fig. 3A and C, compare Gic2p and Gic2pcrib−), suggesting that its binding to activated Cdc42p is necessary for polarization. Taken together, these results demonstrate that at bud emergence, recruitment of Bni1p, Bud6p, and Gic2p to the cell cortex is not solely dependent on an intact actin cytoskeleton but requires activation of the Cdc28p-Clnp kinase.

FIG. 3.

Localization of Gic2p, Bud6p, and Bni1p at bud emergence is independent of an intact actin cytoskeleton but requires Cdc28p-Clnp kinase. (A) Wild-type cells (K699) were released at 30°C from their block in G0 in the presence of LatA, and the localization of the indicated GFP fusion proteins was analyzed by GFP microscopy at time zero (G0, upper rows) and at bud emergence after 3 h (G1; lower rows). Gic2pcrib−, which is unable to bind Cdc42p (8), was included as a control. The numbers indicate the percentage of cells that localized the indicated GFP fusion protein to the incipient bud site; at least 200 cells were analyzed for each strain. (B) The results were quantified (right panels) and plotted as time after release (in minutes) versus percent Gic2p (upper panel) or Bni1p (lower panel) localized to the incipient bud site (solid column), distributed throughout the cytoplasm (not localized; light grey bars) or bud neck localization (others; dark grey bars); at least 200 cells were counted for each time point. Note that Gic2p localizes slightly before Bni1p. (C) cln1,2,3Δ pMETCLN2 (YMG258) cells expressing the indicated GFP fusion proteins from the ADH promoter were arrested in G1 by repression of Cln2p in medium containing methionine. Cells were quickly washed and divided: one half was resuspended in medium containing methionine to repress Cln2p (Cln2p block, upper two rows), the other half was suspended in medium without methionine to induce Cln2p (Cln2p release, lower two rows). Both samples contained LatA to prevent polarization of the actin cytoskeleton. Localization of the GFP-tagged proteins was analyzed after 3 h by fluorescence microscopy. Note that Cdc28p-Cln2p induces polarized localization of Gic2p, Bni1p, Bud6p, and Bud6p1–409 in the absence of an assembled actin cytoskeleton.

Recently, an intact secretion pathway has been implicated in localizing Bud6p to the cell cortex (22). To test whether polarized secretion is required to localize Gic2p, Bni1p, and Bud6p to the incipient bud site, we assayed their localization in sec18-1 mutants (39). Wild-type or sec18-1 cells were released from the G0 block at 37°C to inhibit secretion, and the localization of the GFP-tagged proteins was analyzed as described above. Although Gic2p, Bni1p, and Bud6p localized less efficiently in sec18-1 than in wild-type cells, a significant portion was able to assemble at the incipient bud site in the absence of a functional secretion pathway (Fig. 4). Thus, at least at bud emergence, these proteins are likely to assemble at the cell cortex by binding to a cortical marker.

FIG. 4.

Localization of Gic2p, Bud6p, and Bni1p at bud emergence is mostly independent of an intact secretion pathway. Wild-type (WT; S288C) and sec18-1 (MJ756) cells were released from their block in G0 (time zero), shifted to 37°C, and analyzed for the localization of Gic2p (left panels), Bni1p (middle panels), and Bud6p (right panels) by GFP microscopy after the times indicated (in minutes). The results were quantified and plotted as described in the legend to Fig. 3B. At least 200 cells were counted for each time point.

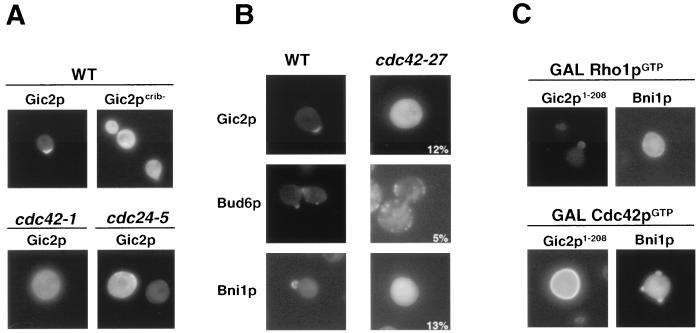

Gic2p interacts with Cdc42p through an amino-terminal CRIB motif, and a Gic2p mutant protein unable to interact with Cdc42p-GTP (Gic2pcrib−) is nonfunctional and distributed throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 5A) (8). Supporting these results, Gic2p was also cytoplasmic in mutants defective for Cdc24p or Cdc42p function (Fig. 5A). Likewise, Gic2p, Bni1p, and Bud6p failed to localize in cdc42-27 mutant cells (Fig. 5B), suggesting that Cdc42p is required to localize these proteins to the presumptive bud site. Conversely, overexpression of Cdc42p-G12V (GAL Cdc42pGTP) but not Rho1p-Q86L (GAL Rho1pGTP) in wild-type cells was able to uniformly recruit Gic2p1–208 to the plasma membrane (Fig. 5C), while Bni1p was found at the incipient bud site under the same conditions. The use of Gic2p1–208 was necessary to prevent degradation of Gic2p, which is induced by Cdc42p-GTP (21). Overexpression of Rho1p-GTP was only weakly able to recruit Bni1p to the plasma membrane (Fig. 5C), and in most of the cells (over 70%) Bni1p was uniformly distributed throughout the cytoplasm.

FIG. 5.

Localization of Gic2p, Bud6p, and Bni1p to the incipient bud site is dependent on Cdc42p-GTP. (A) Localization of Gic2p is dependent on the presence of Cdc42pGTP. The localization of Gic2p-GFP and Gic2pcrib−-GFP was analyzed in wild-type (K699), cdc42-1 (MJ391), and cdc24-5 (YMP483) cells grown at 25°C in selective medium after a shift to the restrictive temperature (37°C) for 2 h. (B) The localization of GFP-tagged Gic2p (upper panel), Bud6p (middle panel), and Bni1p (lower panel) at bud emergence was analyzed by GFP microscopy in wild-type (K699) and cdc42-27 (MOSY0124) cells grown in selective medium at 25°C and shifted to 37°C for 2 h. The numbers indicate the percentage of cells that localized Gic2p-GFP to the incipient bud site; at least 200 cells were analyzed for each strain. (C) The localization of Gic2p1–208-GFP (left panels) and Bni1p-GFP (right panels) was determined by GFP microscopy in cells overexpressing Cdc42p-G12V (Cdc42pGTP; lower panels) or Rho1p-Q86L (Rho1pGTP; upper panels). Note that Cdc42pGTP is able to uniformly recruit Gic2p but not Bni1p to the plasma membrane.

The localization of Bni1p and Bud6p to the incipient bud site is dependent on the Gic proteins.

Gic2p was efficiently localized to the presumptive bud site in bud6Δ and bni1Δ cells released from the G0 block in the presence of LatA (Fig. 6A). In addition, Gic2p was initially found at the site of polarization in bni1Δ and bud6Δ cells exposed to α-factor, although the cells are defective in forming mating projections (Fig. 6B). Thus, Bni1p and Bud6p are not required to localize Gic2p to the site of polarization, suggesting that they may function independently or downstream of Gic2p. In contrast, Bni1p and both full-length and the amino-terminal domain of Bud6p (Bud6p1–409) failed to localize to the presumptive bud site in gic1Δ gic2Δ cells (Fig. 6C), while Cdc24p and Bem1p (data not shown) localized efficiently. Quantitation of these results revealed that over 90% (n = 375) of the gic1Δ gic2Δ cells were unable to localize Bni1p, Bud6p, or Bud6p1–409 at bud emergence, while Cdc24p and Bem1p were found at the incipient bud site in approximately 50% (n = 210) of the cells. Thus, these results imply that the Gic proteins may be involved in recruiting or stabilizing Bni1p and Bud6p at the incipient bud site. However, in the few gic1Δ gic2Δ cells which were able to form a bud, Bni1p or Bud6p was localized efficiently to bud tips and later to the mother bud neck, demonstrating that Gic1p and Gic2p are not the only components capable of localizing them to sites of polarized growth. Finally, overexpression of Bni1p or Bud6p was able to partially restore the shmoo defect of gic1Δ gic2Δ cells (Fig. 6D), and many cells polarized towards multiple sites (inset). Bnip and Bud6p localized to shmoo tips under these conditions, suggesting that increased levels of Bni1p or Bud6p are able to bypass the need for the Gic proteins in response to pheromones. Taken together, these results suggest that the Gic proteins function upstream of Bni1p and Bud6p and may be involved in their recruitment to the incipient bud site in response to activated Cdc42p.

FIG. 6.

Localization of Bni1p, Bud6p, and Bud6p1–409 at bud emergence is dependent on the Gic proteins. (A and B) The localization of Gic2p at bud emergence (A) and in response to pheromones (B) is independent of BUD6 and BNI1. Wild-type (WT; upper panels; K699), bni1Δ (middle panels; MJ491), and bud6Δ (bottom panels; MJ493) cells were released from the block in G0 as described in the legend to Fig. 4A or treated with α-factor for the times indicated (B), and the localization of Gic2p-GFP was analyzed by GFP microscopy. (C) The localization of Bni1p (upper panels), Bud6p, Bud6p1–409 (middle panels), and Cdc24p (bottom panels) at bud emergence was analyzed after G0 release in gic1Δ gic2Δ cells (MJ717) at 37°C. The numbers indicate the percentage of cells that localized the indicated GFP fusion protein to the incipient bud site; at least 200 cells were analyzed for each strain. Note that in contrast to Cdc24p, the localization of Bni1p and Bud6p at bud emergence requires the Gic proteins. (D) Overexpression of Bni1p (upper panels) and Bud6p (middle panels) suppresses the shmoo defect of gic1Δ gic2Δ cells (MJ717). The localization of Bud6p-GFP and Bni1p-GFP was determined by GFP microscopy (left panels). The ability of these cells to form mating projections was quantified (inset); bars represent the percentage of total cells with the indicated morphology. At least 200 cells were counted for each experiment. Note that overexpression of Bni1p triggers formation of multiple mating projections (shaded bar).

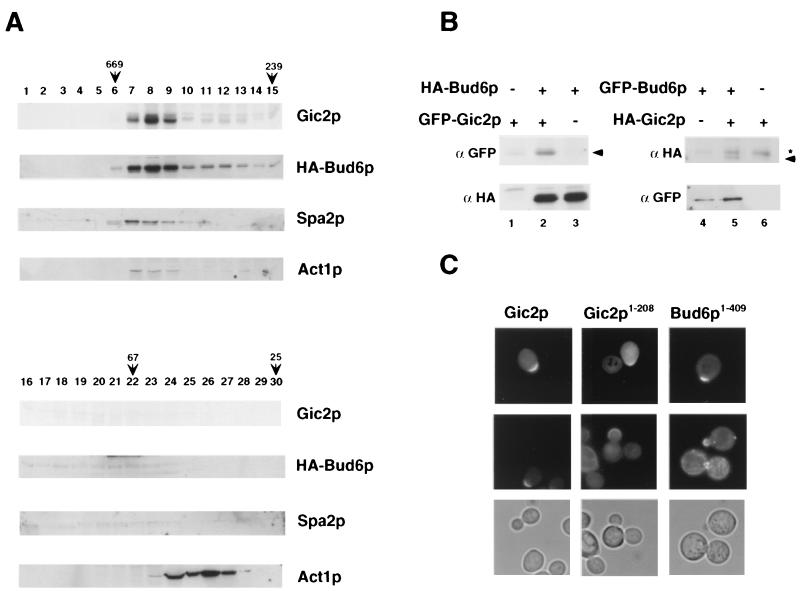

Gic2p may associate with Bud6p at bud emergence.

To examine whether Gic2p associates with Bud6p and Spa2p, we analyzed the distribution of Gic2p-containing complexes by gel filtration (Fig. 7A) and sucrose gradients (data not shown). The majority of Gic2p was recovered in a single peak of approximately 600 kDa. A small fraction of actin was part of this complex, but it was mainly found in complexes of about 40 kDa (bottom panel). Interestingly, the distribution of Gic2p overlapped that of Bud6p and Spa2p (middle panels), suggesting that Gic2p may be a component of a common complex (46). Indeed, a fraction of Gic2p coimmunoprecipitated with Bud6p (Fig. 7B), and Bud6p and Pea2p also interacted with Gic2p in a two-hybrid assay (Table 3). Because Gic2p is only expressed in the G1 phase of the cell cycle, it is expected that not all of Bud6p will be in a complex with Gic2p. The interaction between Gic2p and Bud6p was mediated by the amino-terminal domain of Gic2p and required an intact CRIB domain (Table 3), while conversely, Gic2p interacted with the amino-terminal domain of Bud6p (Table 3). In contrast, Bni1p, Pea2p, and Spa2p bind to the carboxy-terminal domain of Bud6p (C. Boone, personal communication), indicating that their binding site is separable from Gic2p. Importantly, the amino-terminal domains of both Gic2p and Bud6p fused to GFP were sufficient to localize to the incipient bud site (Fig. 7C) (22), implying that the signals for correct localization are present within these domains. Taken together, these results indicate that at bud emergence Gic2p may associate with a large complex by interacting with the amino-terminal domain of Bud6p, which is necessary and sufficient to localize to the incipient bud site in vivo (22).

FIG. 7.

Gic2p cofractionates with Bud6p and Spa2p and coimmunoprecipitates with a fraction of Bud6p. (A) Total cell extracts were separated by gel filtration and analyzed by immunoblotting for Gic2p, HA-Bud6p, Spa2p, and actin as indicated. Fraction numbers are shown above; the positions of the molecular size markers detailed in the text are indicated by arrows. (B) HA-Bud6p was immunoprecipitated with HA11 antibodies (lanes 1 to 3), and the precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting for the presence of bound Gic2p-GFP (αGFP; upper left panel) or HA-Bud6p (αHA; lower left panel). A small amount of Gic2p precipitated nonspecifically (lane 1). In addition, GFP-Bud6p was immunoprecipitated with GFP antibodies (lanes 4 to 6) and blotted for the presence of HA-Gic2p (upper right panel) or GFP-Bud6p (lower right panel). The arrowhead marks the position of GFP- and HA-Gic2p (left and right, respectively); the asterisk points to an unspecific protein recognized by the HA11 antibody. (C) The amino-terminal domains of Gic2p (Gic2p1–208; middle panels) and Bud6p (Bud6p1–409; right panels) fused to GFP are sufficient for localizing the proteins to the incipient bud site. Note that full-length Gic2p (left panels) but not Gic2p1–208 is degraded after bud emergence.

TABLE 3.

Two-hybrid analysisa

| DNA-binding domain | Activation domain | β-Galactosidase activity (mean Miller units ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Bud6p | Gic2p | 134 ± 15 |

| Gic2p1–208 | 101 ± 2 | |

| Gic2pW23A | 19 ± 4 | |

| Gic2pcrib− | 21 ± 2 | |

| Vector | 9 ± 2 | |

| Bud6p1–409 | Gic2p | 383 ± 41 |

| Gic2p1–208 | 191 ± 36 | |

| Gic2pW23A | 19 ± 2 | |

| Gic2pcrib− | 9 ± 1 | |

| Vector | 15 ± 1 | |

| Vector | Gic2p | 15 ± 1 |

| Gic2p1–208 | 6 ± 1 | |

| Gic2pW23A | 12 ± 1 | |

| Gic2pcrib− | 1 ± 0 | |

| Pea2p | Gic2p | 187 ± 8 |

| Gic2pW23A | 25 ± 4 | |

| Vector | 17 ± 1 | |

| Cdc42pC188S | Gic2p | 3,912 ± 148 |

| Gic2pW23A | 3,847 ± 199 | |

| Gic2pcrib− | 20 ± 3 | |

| Gic2pW23A/crib− | 21 ± 9 | |

| Vector | 30 ± 0 |

Wild-type and various mutants of Gic2p fused to an activation domain were tested by two-hybrid analysis for their ability to interact with Cdc42p, Pea2p, and Bud6p fused to a DNA-binding domain. Expression of the β-galactosidase reporter was quantified and is shown as Miller units with standard deviations averaged from three independent colonies.

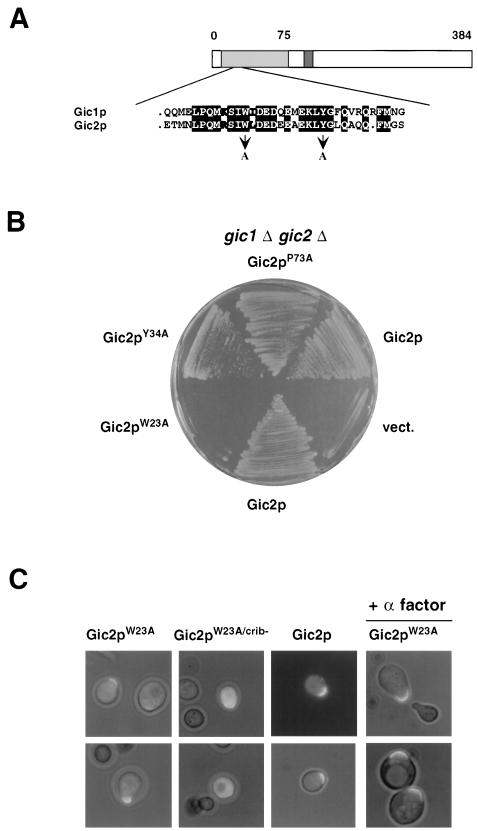

Conserved amino-terminal domain of Gic2p required for its polarization function.

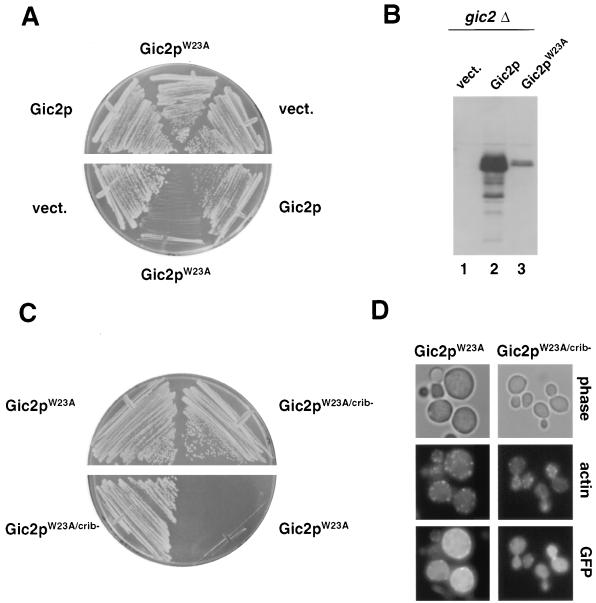

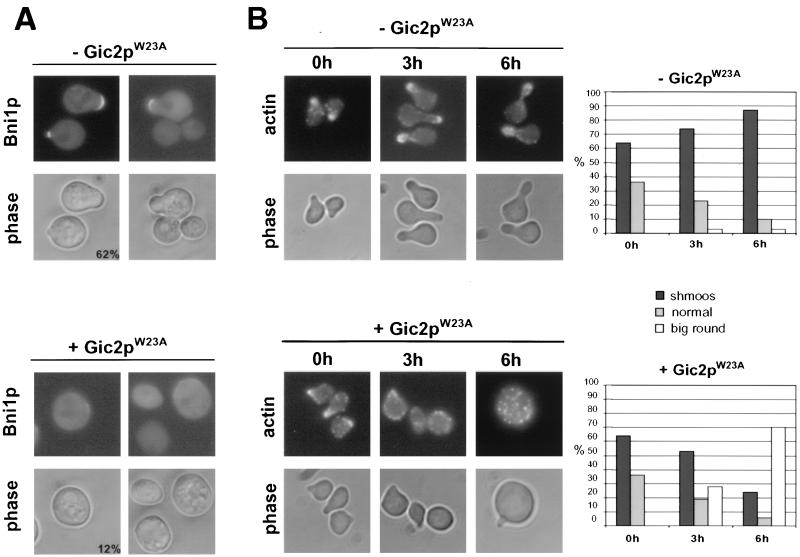

Besides the CRIB domain, the amino terminus of Gic2p contains a 50-amino-acid stretch which has 65% sequence identity with Gic1p (Fig. 8A). To test whether this domain may be involved in the polarization function of Gic2p, we mutated several conserved amino acids in this motif (panel A) and expressed the mutated proteins in gic1Δ gic2Δ cells (panel B). Gic2pW23A mutant protein failed to restore growth of gic1Δ gic2Δ cells at 37°C, indicating that this domain is essential for Gic2p function. Gic2pW23A interacted efficiently with Cdc42p (Table 3), and the protein was localized to the presumptive bud or shmoo site in a CRIB-dependent manner (Fig. 8C), suggesting that it is defective for functionally interacting with downstream targets. Gic2pW23A prevented bud emergence in a dominant-negative manner: wild-type cells expressing Gic2pW23A from the inducible GAL promoter were unable to form colonies on plates containing galactose (Fig. 9A), although the protein was expressed at lower levels than wild-type Gic2p (panel B). Gic2pW23A was still rapidly degraded (data not shown), excluding the possibility that Gic2pW23A interfered with bud emergence because of a defect in its ubiquitin-mediated degradation. Cells expressing Gic2pW23A arrested with a single nucleus (data not shown), large unbudded morphology, and an unpolarized actin cytoskeleton (Fig. 9D). Gic2pW23A was also able to prevent shmoo formation in response to pheromones (Fig. 10A), suggesting that Gic2pW23A interferes with cytoskeletal polarization. Consistent with a role in blocking Cdc42p function, cells expressing Gic2pW23A in combination with a nonfunctional CRIB domain (Gic2pW23A/crib−) were able to grow efficiently (Fig. 9C). Interestingly, Bni1p-GFP and Bud6p-GFP failed to localize to the cell cortex in pheromone-treated cells expressing Gic2pW23A (Fig. 10A and data not shown), although Gic2pW23A was properly localized to the site of polarisation (Fig. 8C and data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that Gic2pW23A may prevent bud emergence by blocking access of downstream components to activated Cdc42p. Indeed, Gic2pW23A was defective in interacting with Bud6p and Pea2p in a two-hybrid assay (Table 3), indicating that Gic2pW23A may prevent recruitment of these components to the site of polarization. Gic2pW23A was also able to interfere with polarized growth after a fully polarized actin cytoskeleton had already been established (Fig. 10B). In these experiments, expression of Gic2pW23A was induced by the addition of galactose at time zero to cells which were already fully polarized by pheromones, and the morphology and polarization state were examined after 3 and 6 hours. Clearly, cells expressing Gic2pW23A lost their actin polarization and instead incorporated new cell wall material all over their surface. We conclude from these results that Gic2pW23A is able to interfere with the actin cytoskeleton in already polarized cells, implying that activated Cdc42p is required not only to establish but also to maintain cellular polarization.

FIG. 8.

Analysis of a Gic2p mutant (Gic2pW23A) defective for cytoskeletal polarization. (A) Schematic representation of the Gic2p. Dark grey bar, CRIB domain; shaded bar, domain with high degree of conservation between Gic1p and Gic2p. The alignment highlights a conserved domain between Gic1p and Gic2p; the mutated amino acids are indicated below. Identical amino acids are shown with black boxes; similar amino acids are shaded. Note that the amino-terminal domain (amino acids 1 to 208) of Gic2p is sufficient for its actin polarization function in vivo (21). (B) gic1Δ gic2Δ cells (MJ398) harboring an empty control vector (vect.) or a centromeric plasmid expressing either wild-type (Gic2p) or the indicated mutant Gic2 proteins from the endogenous promoter were grown for 3 days on selective medium at 37°C. Note that Gic2pW23A is unable to restore growth. (C) Localization of GFP fused to wild-type Gic2p, Gic2pW23A, or Gic2pW23A/crib expressed in wild-type cells (K699) from the inducible GAL promoter. The photographs were taken 150 min after addition of galactose and show GFP fluorescence overlaid with phase contrast images. Where indicated, α-factor was added for 3 h (+α-factor). Note that Gic2pW23A localizes to the incipient bud site or the shmoo tip in a CRIB-dependent manner.

FIG. 9.

Gic2pW23A interferes with cellular polarization in a dominant-negative manner. (A) Wild-type cells (K699) cells were transformed with a control plasmid (vect.) or plasmids expressing wild-type Gic2p or Gic2pW23A from the inducible GAL promoter. Cells were grown for 3 days at 30°C on selective medium containing glucose (upper half; GAL promoter off) or galactose (lower half; GAL promoter on). (B) The expression of wild-type Gic2p (lane 2) and Gic2pW23A (lane 3) was determined in gic2Δ cells by immunoblotting with polyclonal Gic2p antibodies. Lane 1 (vect.) confirms the specificity of the Gic2p antibodies. (C) The dominant phenotype of Gic2pW23A is dependent on its ability to interact with Cdc42p. Wild-type cells (K699) were transformed with plasmids expressing from the inducible GAL promoter Gic2pW23A or Gic2pW23A/crib−, which is defective for its interaction with Cdc42p (Table 3). Cells were grown for 3 days at 30°C on selective medium containing glucose (upper half; GAL promoter off) or galactose (lower half; GAL promoter on). (D) Cells expressing GFP fusions to Gic2pW23A or Gic2pW23A/crib− from the inducible GAL promoter were grown at 30°C to exponential phase in selective medium containing raffinose, at which time galactose was added for 6 h. Cells were stained with rhodamine-phalloidin to visualize the actin cytoskeleton (middle row); the lower row shows GFP fluorescence. Note that cells expressing Gic2pW23A arrest with a large unbudded morphology and an unpolarized actin cytoskeleton.

FIG. 10.

Expression of Gic2pW23A prevents localization of Bni1p and perturbs mating projections. (A) gic2Δ cells expressing Gic2pW23A from the inducible GAL promoter (MJ631) and harboring a plasmid encoding BNI1-GFP were grown at 30°C in selective medium containing raffinose until early log phase, at which time expression of Gic2pW23A was induced by the addition of galactose (lower rows, +Gic2pW23A); as a control, glucose was added to half of the culture to repress expression of Gic2pW23A (upper rows, − Gic2pW23A). After 1 h, α-factor was added, and cells were analyzed 2 h later by GFP fluorescence and phase microscopy. The numbers indicate the percentage of cells that were able to form mating projections; at least 200 cells were analyzed for each strain. Note that Gic2pW23A interferes with shmoo formation and prevents asymmetric localization of GFP-Bni1p. Upper panels, GFP fluorescence; lower panels, phase contrast. (B) gic2Δ cells expressing Gic2pW23A from the inducible GAL promoter (MJ631) were grown at 30°C in selective medium containing raffinose to mid-log phase, at which time actin polarization was triggered by the addition of α-factor. After 2 h, the culture was divided (time zero); in one half, expression of Gic2pW23A was induced by the addition of galactose (lower rows, + Gic2pW23A), and in the other half Gic2pW23A was repressed by the addition of glucose (upper rows, − Gic2pW23A). After 3 (middle column) or 6 h (right column), the polarization state of the cells was examined by actin staining with rhodamine-phalloidin (actin, upper rows) or phase contrast microscopy (phase, lower rows). The results were quantified (right panels) and plotted as time (in hours) after addition of glucose (upper graph, − Gic2pW23A) or galactose (lower graph, + Gic2pW23A) versus percentage of cells with the indicated morphology. At least 200 cells were counted for each time point. Note that expression of Gic2pW23A is able to perturb the cell polarity of existing mating projections.

DISCUSSION

Gic2p and the Bni1p, Bud6p, Spa2, and Pea2p group of proteins may function in both common and distinct pathways.

GIC2 showed multiple genetic interactions with BUD6, BNI1, and SPA2, which indicates that these proteins function in both common and distinct pathways. In particular, overexpression of Gic2p was toxic in bni1Δ, spa2Δ, and bud6Δ cells, and conversely, deletion of BNI1, SPA2, or BUD6 was lethal in gic2Δ cells at elevated temperatures. In both situations cells were unable to polarize their cytoskeleton at bud emergence, similar to overexpression of a stable Gic2p in wild-type cells (21). We speculate that deletion of Gic2p in these mutants may prevent formation of polarization sites, while overexpression of Gic2p may uniformly activate polarization all over their cell cortex. In the absence of Bud6p, Bni1p, or Spa2p, actin polarization may be delayed or altered, enabling Gic2p to establish additional polarization sites at the cell cortex. Alternatively, these components may play both positive and negative roles during actin polarization, similar to mitogen-activated protein kinases that repress transcription in the absence of an activating signal (35). In this hypothetical scenario, Bni1p, Bud6p, and Spa2p may prevent the use of sites at the cell cortex which are not normally available but could be developed with an excess amount of Gic2p. Finally, we cannot exclude that overexpressed Gic2p may interfere with components of the secretion pathway, thereby targeting secretion not just to the polarization site but instead all over the cell cortex.

The synthetic interactions between gic2Δ and bni1Δ, bud6Δ, and spa2Δ cells indicate that these proteins may function in parallel pathways. Indeed, bni1Δ, bud6Δ, and spa2Δ mutants exhibit bud site selection defects which are not observed in gic1Δ gic2Δ cells (5). Likewise, either GIC1 or GIC2 is needed for polarized growth at elevated temperatures, while cells lacking Bni1p, Bud6p, or Spa2p are viable, implying that the Gic proteins may have additional targets. However, the synthetic interactions do not exclude that the Gic proteins may also function upstream of Bni1p, Bud6p, or Spa2p in a common pathway. In particular, additive phenotypes are often observed with proteins that function in large complexes, where deletion of one component may only partially inactivate the complex. For example, bud6Δ spa2Δ double mutant cells are temperature sensitive (46), although the two proteins function, at least in part, in a common complex. In addition, Gic2p shares some of its functions with Gic1p (8, 10), and likewise, Bni1p has overlapping roles with Bnr1p (19). Thus, only cells deleted for both components may unravel the full phenotype, although the two proteins function in the same pathway. Consistent with this notion, cells lacking both GIC genes and bni1Δ, bud6Δ, and spa2Δ cells share multiple actin abnormalities, including defects in spindle positioning and polar bud growth, and they fail to form pseudohyphae or mating projections (5, 8, 10, 32, 36). Interestingly, overexpression of Bni1p or Bud6p suppressed the shmoo defect of gic1Δ gic2Δ cells, indicating that the Gic proteins may function upstream of or in parallel to Bni1p and Bud6p. However, it is important to note that Gic2p is rapidly degraded shortly after bud emergence (21), suggesting that the role of the Gic proteins may be restricted to the G1 phase of the cell cycle.

Gic2p associates with a large complex containing Bud6p.

Available evidence suggests that at bud emergence Gic2p may be part of a large complex containing Bud6p, Bni1p, Pea2p, and Spa2p. Gic2p cofractionated with Bud6p and Spa2p, and Bud6p and Pea2p were able to interact with Gic2p in a two-hybrid assay. A fraction of Bud6p was also able to coimmunoprecipitate with Gic2p; because Gic2p is only present on G1, it is expected that only substochiometric amounts of Bud6p are associated with Gic2p. In addition, binding of Bud6p was dependent on an intact CRIB domain, suggesting that Cdc42p may regulate their interaction. A similar mechanism activates the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein, where binding of Cdc42p was shown to relieve intramolecular inhibition by unmasking a binding domain for the Arp2/3 complex (25). Bud6p interacts with the amino terminus of Gic2p, which is both necessary and sufficient for its polarization function in vivo (21). The amino terminus contains several motifs which are conserved between Gic1p and Gic2p (8, 10); W23 lies within one of these motifs and was required for the polarization function of Gic2p but not for binding of Cdc42p or its localization to the incipient bud site. Interestingly, Gic2pW23A failed to interact with Bud6p and Pea2p in a two-hybrid assay, suggesting that this domain may be required for their binding. Expression of Gic2pW23A interfered with cellular polarization in a dominant-negative manner; the phenotype of the arrested cells strongly resembles that of cdc42 or cdc24 mutant cells (24), although the cells were able to activate Cdc42p. Similarly, a fusion protein between the CRIB domain and GFP (GFP-crib) was able to localize to the incipient bud site but subsequently blocked bud emergence (M.-P. Gulli and M. Peter, unpublished results). Taken together, these results suggest that Gic2pW23A may sequester active Cdc42p at the cell cortex and possibly blocks downstream functions of Cdc42p-GTP by preventing recruitment or activation of components involved in actin organization, including Bni1p and Bud6p.

Gic2p may be involved in recruiting Bud6p and Bni1p to activated Cdc42p at bud emergence.

Several lines of evidence suggest that Gic2p may regulate the recruitment of Bud6p and Bni1p to the cell cortex at bud emergence. First, Gic2p, Bni1p, and Bud6p all colocalize to the incipient bud site and at tips of mating projections, and this localization depends on functional Cdc42p. Second, gic1Δ gic2Δ cells failed to localize Bni1p and Bud6p to the site of polarization, whereas bni1Δ and bud6Δ cells localized Gic2p efficiently. Finally, Gic2pW23A, which is defective for its interaction with Bud6p and Pea2p, interfered with recruitment of Bni1p and Bud6p to activated Cdc42p in vivo. Because the Gic proteins are not required to activate Cdc42p (8; Gulli and Peter, unpublished results), we suggest that they may be involved in targeting a complex containing Bud6p, Spa2p, Pea2p, and Bni1p to the incipient bud site. This initial recruitment appears to be independent of a polarized actin cytoskeleton or an intact secretory pathway, because it occurs in the presence of LatA and in sec18-1 mutant cells shifted to the restrictive temperature. We thus propose that Gic2p may function as an adaptor which links activated Cdc42p to Bud6p, Bni1p, Pea2p, and Spa2p, thereby localizing this complex to the site of polarization. However, there are at least two important considerations for this model. First, Gic2p is rapidly degraded shortly after bud emergence and is absent during later stages of the cell cycle (21), implying that Gic2p is not required to maintain these components at bud tips or to localize them to the mother bud neck. Second, GIC-independent mechanisms must exist, because the Gic proteins are only essential for their localization to the bud site at elevated temperature. Bni1p interacts with several Rho-GTPases, including Cdc42p (12, 19, 26), and the Rho1p interaction domain is necessary for its subcellular localization in vivo (13). In addition, the localization of Bni1p requires Spa2p (13), while localization of Bud6p is at least partially dependent on an intact secretion pathway (22). We thus propose that after degradation of the Gic proteins, Bni1p and Bud6p may remain at bud tips by directly interacting with Rho-GTPases or by targeted delivery through the secretory pathway. Interestingly, Msb3p and Msb4p were recently shown to functionally replace the Gic-proteins predominantly in diploid cells (5), and indeed, GIC2 was repressed by increased ploidy (14). Importantly, gic1Δ gic2Δ msb3Δ msb4Δ cells are inviable, while overexpression of Msb3p or Msb4p restores growth to gic1Δ gic2Δ cells at elevated temperature (5). Thus, Msb3p and Msb4p may be responsible for localizing Bni1p, Spa2p, Pea2p, and Bud6p to the incipient bud site in the absence of the GIC proteins. However, while together these proteins are essential for viability, at least cells deleted singly for Bni1p, Bud6p, Pea2p, or Spa2p are viable, implying that these components may not be the only targets recruited to the incipient bud site by the Gic1 and Gic2 and perhaps the Msb3 and Msb4 proteins.

At present, no mammalian homologs of the Gic proteins have been identified, although at least Bni1p and Bud6p have remained conserved through evolution (4). For example, a homolog of Bud6p has recently been found in Schizosaccaromyces pombe, and this protein is able to correctly localize to polarization sites when expressed in budding yeast (22). In addition, proteins with similar sequence organization and significant sequence homology to Bni1p are involved in linking Rho-GTPases to the actin cytoskeleton in other fungi, nematodes, flies, and mammals (51). It remains to be determined how these components are targeted to activated Cdc42p in higher eukaryotes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Charlie Boone, Danny Lew, Michael Snyder, David Amberg, Anne-Christine Butty, Pamela Silver, Rosine Hagenauer-Tsapis, and Mike Tyers for kind gifts of strains, plasmids, and antibodies and Miranda Sanders and Phil Crews (UCSC) for the synthesis of LatA; work in their laboratory is supported by the NIH. We are grateful to members of the laboratory for helpful discussions, Audrey Petit for help with the SMART system, Nathalie Perrinjaquet for excellent technical assistance, and Bruno Amati and Richard Iggo for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Swiss Cancer League, and a Helmut Horten Incentive Award.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams A E, Johnson D I, Longnecker R M, Sloat B F, Pringle J R. CDC42 and CDC43, two additional genes involved in budding and the establishment of cell polarity in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:131–142. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.1.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Greene Publishing Associates and Wiley-Interscience; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayscough K R, Stryker J, Pokala N, Sanders M, Crews P, Drubin D G. High rates of actin filament turnover in budding yeast and roles for actin in establishment and maintenance of cell polarity revealed using the actin inhibitor latrunculin-A. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:399–416. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.2.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bähler J, Peter M. Cell polarity in yeast. In: Drubin D G, editor. Frontiers in molecular biology: cell polarity. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 21–77. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bi E, Chiavetta J B, Chen H, Chen G C, Chan C S, Pringle J R. Identification of novel, evolutionarily conserved Cdc42p-interacting proteins and of redundant pathways linking Cdc24p and Cdc42p to actin polarization in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:773–793. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.2.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blondel M, Alepuz P M, Huang L S, Shaham S, Ammerer G, Peter M. Nuclear export of Far1p in response to pheromones requires the export receptor Msn5p/Ste21p. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2284–2300. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.17.2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Botstein D, Amberg D, Mulholland J, Huffaker T, Adams A, Drubin D, Stearns T. The yeast cytoskeleton. In: Jones E W, Pringle J R, Broach J R, editors. The molecular and cellular biology of the yeast Saccharomyces—cell cycle and cell biology. Vol. 3. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1995. pp. 1–90. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown J L, Jaquenoud M, Gulli M P, Chant J, Peter M. Novel Cdc42-binding proteins Gic1 and Gic2 control cell polarity in yeast. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2972–2982. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.22.2972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burbelo P D, Drechsel D, Hall A. A conserved binding motif defines numerous candidate target proteins for both Cdc42 and Rac GTPases. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29071–29074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen G C, Kim Y J, Chan C S. The Cdc42 GTPase-associated proteins Gic1 and Gic2 are required for polarized cell growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2958–2971. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.22.2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eby J J, Holly S P, van Drogen F, Grishin A V, Peter M, Drubin D G, Blumer K J. Actin cytoskeleton organization regulated by the PAK family of protein kinases. Curr Biol. 1998;8:967–970. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)00398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evangelista M, Blundell K, Longtine M S, Chow C J, Adames N, Pringle J R, Peter M, Boone C. Bni1p, a yeast formin linking Cdc42p and the actin cytoskeleton during polarized morphogenesis. Science. 1997;276:118–122. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujiwara T, Tanaka K, Mino A, Kikyo M, Takahashi K, Shimizu K, Takai Y. Rho1p-Bni1p-Spa2p interactions: implication in localization of Bni1p at the bud site and regulation of the actin cytoskeleton in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1221–1233. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.5.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galitski T, Saldanha A J, Styles C A, Lander E S, Fink G R. Ploidy regulation of gene expression. Science. 1999;285:251–254. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guthrie C, Fink G R. Guide to yeast genetics and molecular biology. Methods in enzymology. Vol. 194. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall A. Rho GTPases and the actin cytoskeleton. Science. 1998;279:509–514. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holly S P, Blumer K. PAK-family kinases regulate cell and actin polarization throughout the cell cycle of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:845–856. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.4.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imamura H, Tanaka K, Hihara T, Umikawa M, Kamei T, Takahashi K, Sasaki T, Takai Y. Bni1p and Bnr1p: downstream targets of the Rho family small G-proteins which interact with profilin and regulate actin cytoskeleton in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1997;16:2745–2755. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ito H, Fukuda Y, Murata K, Kimura A. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:163–168. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.163-168.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaquenoud M, Gulli M P, Peter K, Peter M. The Cdc42p effector Gic2p is targeted for ubiquitin-dependent degradation by the SCFGrr1 complex. EMBO J. 1998;17:5360–5373. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin H, Amberg D C. The secretory pathway mediates localization of the cell polarity regulator Aip3p/Bud6p. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:647–661. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.2.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson D I. Cdc42: an essential Rho-type GTPase controlling eukaryotic cell polarity. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:54–105. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.1.54-105.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson D I, Pringle J R. Molecular characterization of CDC42, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene involved in the development of cell polarity. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:143–52. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.1.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim A S, Kakalis L T, Adbdul-Manan N, Liu G A, Rosen M K. Autoinhibition and activation mechanisms of the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein. Nature. 2000;404:151–158. doi: 10.1038/35004513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kohno H, Tanaka K, Mino A, Umikawa M, Imamura H, Fujiwara T, Fujita Y, Hotta K, Qadota H, Watanabe T, Ohya Y, Takai Y. Bnip1 implicated in cytoskeletal control is a putative target of Rho1p small GTP binding protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1996;15:6060–6068. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kron S J, Gow N A. Budding yeast morphogenesis: signalling, cytoskeleton and cell cycle. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:845–855. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kunkel T A, Roberts J D, Zakour R A. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:367–382. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leberer E, Thomas D Y, Whiteway M. Pheromone signalling and polarized morphogenesis in yeast. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leberer E, Wu C L, Leeuw T, Fourestlieuvin A, Segall J E, Thomas D Y. Functional characterization of the Cdc42p binding domain of yeast Ste20p protein kinase. EMBO J. 1997;16:83–97. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lechler T, Shevchenko A, Li R. Direct involvement of yeast type I myosins in Cdc42-dependent actin polymerization. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:363–373. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.2.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee L, Klee S K, Evangelista M, Boone C, Pellman D. Control of mitotic spindle position by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae formin Bni1p. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:947–961. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.5.947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lew D J, Reed S I. A cell cycle checkpoint monitors cell morphogenesis in budding yeast. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:739–749. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.3.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lew D J, Reed S I. Cell cycle control of morphogenesis in budding yeast. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1995;5:17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(95)90048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Madhani H D, Fink G R. The riddle of MAP kinase signaling specificity. Trends Genet. 1998;14:151–155. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01425-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller R K, Matheos D, Rose M D. The cortical localization of the microtubule orientation protein, Kar9p, is dependent upon actin and proteins required for polarization. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:963–975. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.5.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mulholland J, Preuss D, Moon A, Wong A, Drubin D, Botstein D. Ultrastructure of the yeast actin cytoskeleton and its association with the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:381–391. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.2.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mumberg D, Muller R, Funk M. Yeast vectors for the controlled expression of heterologous proteins in different genetic backgrounds. Gene. 1995;156:119–122. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Novick P, Field C, Schekman R. Identification of 23 complementation groups required for post-translational events in the yeast secretory pathway. Cell. 1980;21:205–215. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peter M, Neiman A M, Park H O, vanLohuizen M, Herskowitz I. Functional analysis of the interaction between the small GTP binding protein Cdc42 and the Ste20 protein kinase in yeast. EMBO J. 1996;15:7046–7059. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peterson J, Zheng Y, Bender L, Myers A, Cerione R, Bender A. Interactions between the bud emergence proteins Bem1p and Bem2p and Rho-type GTPases in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:1395–1406. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.5.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pringle J R, Bi E, Harkins H A, Zahner J E, De Virgilio C, Chant J, Corrado K, Fares H. Establishment of cell polarity in yeast. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1995;60:729–744. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1995.060.01.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pruyne D, Bretscher A. Polarization of cell growth in yeast. I. Establishment and maintenance of polarity states. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:365–375. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schluter K, Jockusch B M, Rothkegel M. Profilins as regulators of actin dynamics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1359:97–109. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(97)00100-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sheu Y J, Santos B, Fortin N, Costigan C, Snyder M. Spa2p interacts with cell polarity proteins and signalling components involved in yeast cell morphogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4053–4069. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.4053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sikorski R S, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Snyder M. The SPA2 protein of yeast localizes to sites of cell growth. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:1419–1429. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.4.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Theriot J A, Mitchison T J. The three faces of profilin. Cell. 1993;75:835–838. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90527-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Valtz N, Peter M. Functional analysis of FAR1 in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1997;283:350–365. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)83029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wasserman S. FH proteins as cytoskeletal organizers. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:111–115. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(97)01217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zahner J E, Harkins H A, Pringle J R. Genetic analysis of the bipolar pattern of bud site selection in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1857–1870. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]