Abstract

Cooking interventions have been criticised for their weak designs and ‘kitchen sink’ approach to content development. Currently, there is no scientific guidance for the inclusion of specific skills in children’s cooking interventions. Therefore, a four step method was used to develop age-appropriate cooking skill recommendations based on relevant developmental motor skills. The steps include: 1) a critical review of academic and publicly available sources of children’s cooking skills recommendations; 2) cooking skill selection, deconstruction and mapping to relevant motor skills; 3) grouping the cooking skills by underlying motor skills for age appropriateness to generate evidence based recommendations; 4) establish face validity using a two-stage expert review, critique and refinement with a multidisciplinary international team. Seventeen available sources of cooking skills recommendations were identified, critiqued and deconstructed and cooking skills mapped to developmental motor skills. These new recommendations consist of 32 skills, across five age categories: 2–3 years, 3–5 years, 5–7 years, 7–9 years, and 9+ years. The proposed recommendations will strengthen programme design by providing guidance for content development targeted at the correct age groups and can act as a guide to parents when including their children in cooking activities at home.

Keywords: Cooking, Children, Motor skills, Education, Intervention, Design

1. Introduction

Childhood obesity has reached global epidemic rates and can have a detrimental impact on a child’s physical and mental wellbeing (Han et al., 2010; Sahoo et al., 2015). While treatment is essential for the management of the current situation, prevention strategies have been promoted and emphasised as an important method for restricting further increases and reducing the prevalence of childhood obesity (Pandita et al., 2016). In the World Health Organisations Report on Ending Childhood Obesity (World Health Organization, 2016), preventive strategies are strongly recommended, and one of the key recommendations is to ‘Make food preparation classes available to children, their parents and carers,’ (World Health Organization, 2016). Additionally, there is immense support from the scientific community for culinary education for children as a behavioural strategy in the prevention of childhood obesity due to its potential to influence dietary behaviours and/or food intake (Cunningham-Sabo & Lohse, 2013; Hoelscher et al., 2013; Lichtenstein and Ludwig, 2010; Nelson et al., 2013; Slater, 2013). Recent research supports the rationale for the inclusion of culinary education in multicomponent obesity prevention interventions, as learning cooking skills at younger ages has been associated with positive dietary outcomes in adulthood (Lavelle et al., 2016a) and cooking skills have been shown to track from adolescence to adulthood (Laska et al., 2012). In addition, preparing meals more frequently at home is associated with a normal BMI and body fat percentage (Mills et al., 2017).

However, criticisms relating to the associations between cooking and food skills with diet quality and health remain (McGowan et al., 2017; Reicks et al., 2014, 2018). These include the presence of relatively weak intervention design, specifically a general lack of control groups and limited underpinning of theory or pedagogical approach in both adult and child interventions (Hersch et al., 2014; McGowan et al., 2017; Reicks et al., 2014, 2018). Furthermore, Wolfson et al. (Wolfson et al., 2017) noted a ‘kitchen sink’ approach to designing cooking and broader food skills programmes, with little indication in the programme as to why and how the content and specific cooking tasks are chosen e.g. is chopping or cutting chosen because it has been linked to improved diet quality or is there a rationale behind the choice of skills. While some of these issues are being addressed through the development of models to help guide the planning and development of cooking programmes, e.g. the CookEd model (Asher et al., 2020), there remains a lack of guidance or rationale for specific skill and/or recipe selection in programmes. It has been previously argued that while there has been an over focus on manual skills in cooking programmes and those required for meal preparation and provision in the socio-cultural and physical food environment, e.g. cognitive, sensorial and organisational skills, have been ignored (Fordyce-Voorham, 2011; Vidgen & Gallegos, 2014). However, the importance of developing an initial grounding in basic manual skills to enable an understanding of more complex cognitive skills cannot be understated, especially for children. As children may not have the cognitive capacities to understand complex skills such as food resource management, and thus beginning with manual skills will help to develop an initial interest that will enable learning of the complex skills at a later stage. This argument is in line with Experiential Learning Theory, where learning is seen as an adaptive process involving the development of skills and knowledge which enables lifelong learning (Kolb, 1984). Thus a ‘hands on’ experiential learning approach, focusing on fun and engagement to encourage lifelong development and learning, including the learning of the more complex skills could be seen as best for children.

A clear understanding of a child’s development in terms of the biological, psychological and emotional changes that occur from birth to the end of adolescence, is key to ensuring that a child is able to achieve the targets set for them as milestones. From a physical perspective, fine motor skills are the use of small muscles involved in movements that require the functioning of the extremities to manipulate objects (Gallahue et al., 2012). Fine motor skills are a prominent feature of everyday life as they are involved in many activities such as using cutlery for eating and using knives in food preparation (Gallahue et al., 2012; Marr et al., 2003), with some cooking skills requiring gross motor skills such as arm movement in stirring. Recent research has shown that children may not be developing their fine motor skills at a normative rate (Gaul & Issartel, 2016), and also that normal weight children have higher levels of fine motor precision, manual dexterity and gross motor skills than children with obesity (Gentier et al., 2013; Okely et al., 2004; D’Hondt et al., 2011). Therefore, when planning food education programmes relating to children’s cooking skills, in the home, school and research interventions, considering children’s motor coordination is necessary. This also emphasises the need for careful planning in early ages obesity prevention interventions, to maximise the possibility of achieving success.

Furthermore, there is growing support for the return of compulsory Home Economics to the school curriculum as a means of teaching cooking and food skills to young people to enable healthy food choices (Lichtenstein and Ludwig, 2010; McCloat & Caraher, 2019). While there has been a reported need for an integrated and developmentally appropriate food education on schools’ curriculums (McCloat & Caraher, 2019), it has been highlighted that children are entering secondary school with limited basic food knowledge and skills, posing an additional burden on Home Economics teachers (Ronto et al., 2017). This suggests that children are no longer learning basic food or preparation skills in the home environment (Lavelle et al., 2019). A number of factors were identified as contributing to this decline including parental time scarcity, parental fear and uncertainty surrounding what tasks their children should be undertaking in the kitchen (Lavelle et al., 2019). This is leaving children unskilled when entering secondary school, potentially curtailing what is achievable in Home Economics classes (Ronto et al., 2017), where such classes exist, and also removing a facilitator for cooking in adulthood (Lavelle et al., 2016b).

Currently there are no evidence-based age-appropriate cooking skills recommendations for children that can be used as a guide for content development in programmes (both interventions and educational curricula) or for parents to use as a guide in the home environment. Therefore, this research aimed to develop age-appropriate cooking skills recommendations that are aligned with normal motor skill child development patterns.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

A four step process was followed to conduct this research. Firstly, a critical review was conducted of the sourced academic and publicly available literature on age-related cooking skills recommendations for children. In the second step the different cooking skills suggested in these recommendations were collated, deconstructed and mapped onto relevant motor skills. Thirdly, by grouping together different cooking skills underpinned by the related motor skills that were age-appropriate, evidence based age-appropriate cooking skills recommendations were developed. In the final step a two-stage expert review, critique and refinement with a multidisciplinary international team was undertaken to establish the face validity of the proposed recommendations.

2.2. Expert review panel

14 international experts from a range of disciplines related to child education, development and/or cooking who had an interest in the development of guidelines for children’s cooking were invited to take part in the review. The experts were identified through the research team’s networks, snowball sampling and were recruited through email. The response rate was 86%, with 12 of the original 14 experts approached taking part in the review. Nine experts were female and three were male, with experience ranging from 8 to 35 years in their respective fields. These experts were from the Republic of Ireland (5), United States (2), Australia (2), United Kingdom (1), France (1) and Canada (1). The range of disciplines included; Home Economics, cheffing and commercial cooking, cooking research, nutrition and food education, early years education and care, public health, anthropology and human movement science and motor control/development.

2.3. Step 1: critical review and deconstruction

A systematic approach to searching the literature was conducted which identified all peer-reviewed cooking skills recommendations for children. This literature search was conducted on the databases Web of Science, PubMed and PsycINFO in October 2018. For all databases, the following search terminology were used: children, cooking, cooking skills, and motor skills. Searches were not limited by year of publication or language. Articles were screened by title and abstract for relevance. Additionally, grey literature searches were undertaken to access publicly available sources of cooking recommendations for children. The search strategy used for database searches was repeated on the search engine Google to search for all published sources of cooking skills recommendations for children. In order to recover all publicly available children’s cooking skills recommendations, colloquial phrases such as ‘when should a child start cooking’ and ‘children’s cooking recommendation’ were used in searches on Google. These phrases were chosen as they are common ‘non-academic’ (lay person) phrases that would be used by parents for searching for these recommendations. A verification search was conducted using the same approaches as above, on Google Images, to ensure all relevant recommendations were found. A source was considered eligible if it consisted of a set of age ranges between 0 and 13 years, with each age range containing a list of cooking skills. The identified cooking skills recommendations were critiqued and the extracted data inserted into an excel spreadsheet. The data extracted included source of recommendation, type of website, underpinning evidence and expertise of the author (see Table 1), as well as the recommended cooking skills and suggested age ranges.

Table 1.

Publicly available children’s cooking recommendations.

| Source of Recommendation | Name of Source | Type of Source | Experience of author |

|---|---|---|---|

| BBC Good Food (n.d.) A guide to cookery skills by age (BBC Good Food, 2019) | BBC Good Food | Cooking and recipe-posting website from global food media brand of the same name. | No information |

| Sroufe, D. (2017) Cooking at Every Age, Why Kids Should Learn To Cook (Center for Nutrition Studies, 2019) | Nutrition Studies | Education website promoting plant-based diets. | Author of several weight loss and cookery books |

| Meyer, H. (2018) Cooking Skills Every Kid Should Learn by Age 10 (Eating Well, 2019) | Eating Well | Website for food magazine of the same name promoting healthy recipes. | No information |

| Taste of Home (n.d.) Cooking With Kids: A Guide to Kitchen Tasks for Every Age (Taste of Home, 2019) | Taste of Home | Website for food and lifestyle magazine of the same name. | No information |

| Jack, H. (2017) What age can children learn to cook? (Food Sorcery, 2019) | Food Sorcery | Blog of Cookery and Barista School of the same name. | Founder and director of the school |

| Fuentes, L. (n.d.) Teach Your Kids How To Cook By Age (MOMables, 2019) | MOMables | Online meal planning subscription service. | No information |

| The Kitchn (n.d.) How Young Kids Can Help in the Kitchen: A List of Activities by Age (The Kitchn, 2019) | The Kitchn | Online food and lifestyle magazine with articles posted daily consisting of recipes, cooking lessons, product reviews and kitchen design. | No information |

| A Healthier Michigan (2017) An Age-by-Age Guide to Cooking With Your Children (A Healthier Michigan, 2017) | A Healthier Michigan | A healthy lifestyle initiative based in Michigan sponsored by the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan. | No information |

| Seidenerg, C. (2018) How to start teaching your kids to cook: an age-appropriate guide (Oregon Live, 2019) | Oregon Live | Online website for the newspaper The Oregonian. | Co-founder of a nutrition-based education company. Member of Washington D.C. Children’s Hospital Board |

| The Kids Cook Monday (2019) Teaching Kids to Cook (The Kids Cook Monday, 2019) | The Kids Cook Monday | A project of The Monday Campaigns, a global movement encouraging families to improve various aspects of their lifestyles. This project promotes families cooking and eating together one day a week. | Certified nutritionist and cooking instructor. |

| Klemm, S. (2019) Teaching Kids to Cook (Eat Right, 2019) | Eat Right | Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, representing over 100,000 dietitians and other practitioners. | Registered Dietitian Nutritionist |

| Magee, E. (2008) Cooking With Your Children (WebMD, 2019) | Web MD | Online publisher of news and information on the topic of health and wellbeing. | Registered Dietitian and holds Masters in Public Health |

| Gough, K. (2017) Basic Cooking Skills for Kids at Every Age (Metroparent, 2019) | Metro Parent | Online publisher of family-focused publications, events and television segments | No information |

| Canada’s Food Guide (2014) Involving kids in planning and preparing meals (The official website of the government of Canada, 2019) | Canada’s Food Guide | Nutrition guide produced by Health Canada – the national public health department of the Canadian government. | No information |

| National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (n.d.) Getting Kids in the Kitchen, Maryland, USA: National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, 2019) | National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) | Publishes articles and conducts research, training, and education programmes to promote the prevention and treatment of heart, lung, and blood disorders. | No information |

| The Works Blog (2016) Life Skills for Kids: Cooking (The Works, 2019) | The Works | Blog of online shop selling family resources such as games, stationery, gifts and parental resources. | No information |

| Workman, K. (2018) When should kids start helping in the kitchen? Now is good (NewsOk, 2019) | News OK | Website of the newspaper The Oklahoman. | Author of family-orientated cookbooks |

2.4. Step 2: cooking skill selection and deconstruction

In this step, the frequency of appearance of a particular individual skill mentioned in the sourced literature was calculated by coding each cooking skill and then counting each time that cooking skill was mentioned. The refinement of skills was conducted through a process of combining similar skills and omission of skills such as those not considered a ‘cooking skill,’ e.g. ‘setting the table,’ skills that were not a singular skill e.g. ‘making a sandwich,’ or ones that were too food specific e.g. ‘cracking eggs.’ Additionally, cooking skills that appeared less than three times in sourced recommendations were omitted as these were not considered to be common skills required.

Following this, the selected individual cooking skill was deconstructed to determine the various underlying developmental skills that would be needed to complete each cooking skill. The underlying developmental skills that were mapped included fine motor skills, gross motor skills, numeracy, literacy, food hygiene and safety awareness. The outcome of these deconstructions were reviewed by a human movement scientist (JI) and a health researcher (FL) for accuracy.

2.5. Step 3: grouping and classification by motor skills

The cooking skills identified in the selection process were grouped together into motor skill categories, based on common fine motor skills that are required to complete each skill. Two researchers (COK, FL) independently classified the selected cooking skills into the motor skill categories. Both researchers were provided with identical lists of the selected cooking skills and descriptions of each motor skills groups. Any discrepancies were discussed until total agreement was reached on the placement of cooking skills into appropriate categories. The motor skills categories were assigned appropriate ages by mapping them to children’s fine motor skill development ages, i.e. the age at which the motor skills in each category should be developed, with additional aspects such as safety taken into consideration (Gerber et al., 2010; Payne & Isaacs, 2017; Rosenbloom & Horton, 1971). These age based motor skills categories formed the basis of the proposed novel age-appropriate cooking skills recommendations.

2.6. Step 4: two stage face validation through expert review

An expert panel was convened which consisted of five experts from the Republic of Ireland (ROI), France and the UK, who have between 10 and 35 years of experience in their respective fields. The invited experts were informed of the development process of the proposed recommendations from a deconstruction and mapping to developmental skills exercise. They were then independently asked whether they agreed or disagreed on the placement of the cooking skill in each of the age range recommendations and were provided the opportunity to explain their rationale further if they felt it was appropriate. Their evaluations were used to refine the proposed recommendations. Further experts from Australia, USA, Canada and ROI were invited for the second review. The purpose of the second critical review was to gather more global perspectives on the recommendations as the search criteria was not limited to a specific region, and thus increase the cross-cultural applicability of the recommendations. Furthermore, this review acted as a clarification for discrepancies on skill placement after the initial critical review. At this stage seven experts who had 8–30 years of experience took part. At the second review these experts followed a similar process to the first review panel. Their evaluation was used to further refine the recommendations which formed the final proposed age-appropriate recommendations.

3. Results

3.1. Publicly available sources

No relevant peer-reviewed publications were identified from the literature searches. The grey literature searching resulted in 17 publicly available children’s cooking recommendations as seen in Table 1. Of the 17 sources, ten had no author information. Three sources were created by authors from a culinary background, while the other four were created by individuals from a nutrition/medical background. No rationale for the age range appropriateness for each cooking skill was given for any of the publications.

3.2. Cooking skill selection and deconstruction

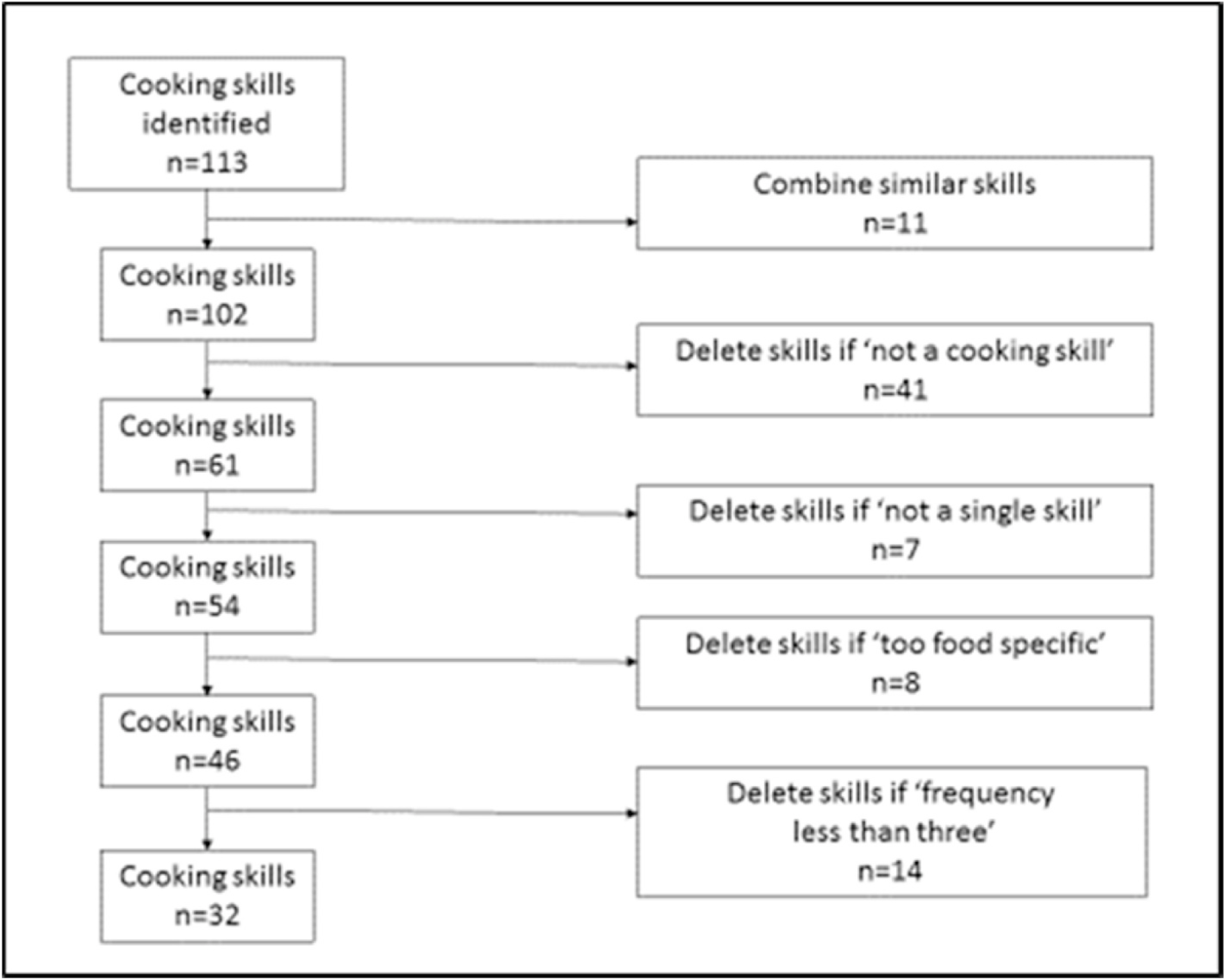

From the 17 available sources, 113 skills termed ‘cooking skills’ were identified. The process of skill selection from the publicly available online sources can be seen in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Results of the cooking skills identification and reasons for exclusion.

Through the selection process the 113 identified skills were reduced to 32 cooking skills, to be included in the proposed recommendations. These 32 cooking skills were deconstructed and mapped to developmental skills as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Deconstruction and mapping of 32 cooking skills to different developmental skills.

| Cooking Skill | Frequency of Appearance through Identified Sources | Deconstruction | Fine Motor Skills | Gross Motor Skills | Food Hygiene and Safety Awareness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Washing Fruit and Vegetables | 18 | Holding items in a palmar grasp and or a pinch between index and thumb under running water | Forming palmar grasp and pincer grasp | Requires strength and movement of arms as well as accuracy | No |

| Stirring and Mixing | 32 | Holding a spoon in closed fist (radial palmar grasp), moving hands and arms in a circle. Holding pot handle using radial palmar grasp or bowl with flat palm spread or raking grasp on bowl edge | Forming radial palmar grasp and engaging intralimb coordination between wrist, elbow and shoulder | Requires strength and movement of arms | No |

| Mashing | 10 | Holding masher or fork in a radial palmar grasp with force, moving hands and arms up and down | Forming radial palmar grasp and engaging intralimb coordination between wrist, elbow and shoulder | Requires strength and movement of arms | No |

| Sprinkling and Rubbing In | 6 | Moving finger tips, rubbing them together, forming pincer grasps between the thumb and each finger | Rubbing fingertips together, forming pincer grasps | Requires strength and movement of arms | No |

| Spooning | 12 | Holding a spoon in radial palmar grasp, keeping a steady hand and firm wrist, rotating wrist to pour ingredients into bowl | Forming radial palmar grasp and differentiating pronation and supunation | Movement of arms and wrist | No |

| Weighing and Measuringa | 15 | Holding a spoon in radial palmar grasp, or a container in an open radial palmar grasp rotating wrist to pour ingredients onto scales | Forming a radial palmar grasp or an open radial palmar grasp | Movement of arms and wrist | No |

| Cutting, Chopping and Slicing | 29 | Forming a firm grip around the knife using radial palmar grasp and lateral prehension, forming a claw around food when holding it | Forming radial palmar grasp with lateral prehension, forming a firm claw to grip food safely and engaging intralimb coordination between wrist, elbow and shoulder | Requires strength and movement of arms | Yes- knowledge of proper way to hold foods (claw) and knowing to be careful when using a sharp knife |

| Breading, Flouring and Dipping | 3 | Lifting up food with a tripod or quadrupod grasp and dipping it | Forming a tripod or quadrupod grasp | Requires strength and movement of arms | No |

| Kneading and Mixing with Hands | 10 | Making claws and moving fingertips with force, pulling and pushing the mixture whilst applying force, opening and closing hands into a palmar grasp | Forming claws and moving fingertips, moving hands open and closed, forming a palmar grasp | Requires strength and movement in arms | No |

| Tearing | 9 | Holding onto food with a palmar grasp and tearing with force | Forming palmar grasp, holding food in hands and pincer grasp | Requires strength and movement of arms | No |

| Using a Rolling Pin | 7 | Rolling a rolling pin with fingers and palms of hands, gripping the rolling pin with a flattened palm and raking grasp | Forming a raking grasp | Moving arms at the elbow, requiring strength and movement of arms | No |

| Using a Cookie Cutter | 6 | Holding cutters using a radial digital grasp and pressing down into dough | Forming a radial digital grasp and pincer grasp | Strength and movement required in arms | No |

| Spreading and Buttering | 9 | Holding knife with radial palmar grasp and lateral prehension with force, moving around the surface being buttered | Forming radial palmar grasp with lateral prehension | Strength and movement of the wrist and forearm | Yes – awareness of possible sharp edge |

| Picking and Podding | 18 | Using tripod grasp to pull apart ingredients | Forming a tripod grasp and quadrupod | Requires strength and movement of arms | No |

| Using Scissors | 5 | Holding scissors with a combination of a palmar radial grasp, raking grasp and open radial palmar grasp | Forming radial palmar grasp, raking grasp and open radial palmar grasp and bilateral coordination | Requires strength and movement of arms | Yes – knowing to be careful with sharp scissors, how to properly carry them |

| Using a Grater | 12 | Holding food with an open radial palmar grasp perpendicular to the grater held in a radial palmar grasp and rubbing the food up and down with force | Forming an open radial palmar grasp and radial palmar grasp | Movement and strength in arms required | Yes – awareness of sharp object, knowing to stop when coming close to the end of the food being grated |

| Greasing | 8 | Holding butter or margarine in digital pronate grasp or quadrupod grasp to spread it across the surface being greased and using finger tips to ensure the whole surface is reached | Forming digital pronate grasp, quadrupod grasp and movement of fingertips | Requires movement and strength of hands and arms | No |

| Peeling with Fingers | 5 | Holding the fruit with palmar grasp and using a digital pronate grasp and tripod grasp to peel skin off | Bending of fingers and finger tips and forming palmar grasp, digital pronate grasp and tripod grasp | Requires strength and movement of arms | No |

| Using a Peeler | 9 | Using a peeler to remove the skin/outer layer of an ingredient, holding it with a palmar grasp and the peeler with a radial palmar grasp or a digital pronate grasp | Holding food with palmar grasp and holding peeler with radial palmar grasp or digital pronate grasp and bilateral coordination | Movement and strength in arms required | Yes – awareness of sharp object |

| Using an Oven or Microwavea | 17 | Turning knobs on oven-top or microwave palmar supinate grasp or inferior pincer grasp, pressing buttons using pointer finger, rotating the wrist. Holding dishes and plates with various grips | Forming palmar supinate grasp or inferior pincer grasp | Ability to stand up and movement of wrist and arms | Yes – awareness of hot surfaces and food and need to use oven gloves |

| Using a Can Opener | 11 | Using a radial palmar grasp to hold onto arms of can opener and palmar supinate grasp to twist the dial of the can opener | Forming open radial palmar grasp and palmar supinate grasp | Strength and movement of arms required | Yes – being careful with sharp edge of can lid |

| Pouring from a Container | 15 | Holding the container or handle using an open radial palmar grasp and moving arm and wrist to pour the ingredient | Forming an open radial palmar grasp and holding onto the liquid ingredients | Some strength and movement of arms required | No |

| Crushing and Pounding | 4 | Holding a mallet, spoon or rolling pin with a radial palmar grasp or an open radial palmar grasp and beating the ingredient to crush or flatten it | Forming radial palmar grasp or open radial palmar grasp | Strength and movements of arms required | No |

| Rolling Mixtures into Balls | 5 | Scooping food up with fingers in raking grasp position and rolling it between palms | Forming raking grasp | Movement in arms required | Yes – working with raw ingredients requires knowledge to not put hands in mouth |

| Squeezing | 8 | Squeezing the fruit in a palmar grasp and using other hand to catch any seeds by cupping the underside of the fruit | Forming a palmar grasp and cupping position | Strength required to squeeze the fruit | No |

| Draining | 4 | Holding the can with an open radial palmar grasp and tipping it into a colander | Forming an open radial palmar grasp | Requires strength and movement of arms | No |

| Scraping Down a Bowl | 4 | Using a spatula, holding it with radial palmar grasp, to scrape batter from bowl, holding the bowl with flat palm spread or raking grasp on bowl edge. | Forming radial palmar grasp and raking grasp | Movement of wrists and arms required | No |

| Skewering | 5 | Holding the skewer using a palmar supinate grasp and the food with an inferior pincer grip, pushing the food onto the skewer | Forming palmar supinate grasp and inferior pincer grasp and pincer grasp | Strength and movement of arms required | Yes – awareness of sharp object |

| Brushing Oil on with a Pastry Brush | 5 | Holding brush with radial palmar grasp or digital pronate grasp, moving the wrist | Forming radial palmar grasp or digital pronate grasp | Moving the wrist and forearm | No |

| Using a Hand Mixer | 5 | Holding the hand mixer with a raking grasp or open radial palmar grasp and moving in circles | Forming a raking grasp or open radial palmar grasp | Strength and movement of arms required | No |

| Breaking Vegetables into Pieces | 3 | Holding the vegetable with a palmar grasp and breaking pieces off using a digital pronate grasp, rotating the wrist | Forming a palmar grasp and digital pronate grasp and bimanual coordination | Movement and strength required in arms, movement of wrist | No |

| Shaking Liquids in a Sealed Container | 3 | Holding container in an open radial palmar grasp and moving arms up and down at the elbow quickly | Forming an open radial palmar grasp | Strength and movement of arms required | No |

Skills that require either numeracy or literacy skills, numeracy required for scale reading, setting timers and temperatures

3.3. Categorisation into recommendations

Deconstruction and mapping of the 32 cooking skills revealed the necessity for four fine motor skills classifications or categories. These included crude hand movements, radial palmer grasp, dynamic quadrupod or tripod grasp and a combination of various grasps. The categorisation of the 32 cooking skills were conducted by two researchers (COK, FL) with an initial inter-rater reliability of 87.5%. All discrepancies were discussed until full agreement was reached and the final categorisation can be seen in Table 3. Each category was assigned an age range in accordance with age ranges of fine motor development; crude hand movements: 2–3 years old, radial palmar grasp: 3–5 years old, dynamic quadrupod or tripod grasp: 5–7 years old, combination of various grasps: 7–9 years old, and those cooking skills that included extra developmental skills such as safety considerations were assigned to a 9+ years old age range.

Table 3.

Fine motor skill classification of cooking skills.

| Motor Skill Category (Gerber et al., 2010; Payne & Isaacs, 2017; Rosenbloom & Horton, 1971) | Crude Hand Movements | Radial Palmar Grasp | Dynamic Quadrupod or Tripod Grasp | Combination of Various Grasps | Additional Skills |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Age Range (Years)

Cooking Skills |

2–3 | 3–5 | 5–7 | 7–9 | 9+ |

| Washing Fruit and Vegetables | Stirring and Mixing | Sprinkling and Rubbing In | Weighing and Measuringd | Stirring and Mixinga | |

| Kneading and Mixing with Hands | Mashing | Breading, Flouring and Dipping | Using a Graterb | Cutting, Chopping and Slicingb | |

| Tearing | Spooning | Picking and Podding | Using an Oven or Microwavead | Using Scissorsb | |

| Using a Rolling Pin | Cutting, Chopping and Slicing | Greasing | Using a Can Openerb | Using a Peeler | |

| Using a Cookie Cutter | Spreading and Buttering | Peeling with Fingers | Crushing and Pounding | Skewering | |

| Rolling Mixtures into Balls | Using Scissorsb | Skeweringb | Pouring from a Container | Weighing and Measuringd | |

| Squeezing | Using a Peelerb | Draining | Using an Oven or Microwavead | ||

| Breaking Vegetables into Pieces | Scraping Down a Bowl | Using a Hand Mixerc | Using a Can Openerb | ||

| Brushing Oil on with a Pastry Brush | Shaking Liquids in a Sealed Container | Using a Hand Mixerc |

The motor skills categorisation of cooking skills is sequential, i.e. older children have the motor skill capacity to accurately perform the skills of the younger children as well as the more complex skills aligned to their age range (Gerber et al., 2010; Payne & Isaacs, 2017; Rosenbloom & Horton, 1971). Superscript letters represent cooking skills that may need to be considered in an older age range due to additional developmental requirements:

safety risk, potential for burns

safety risk, sharp instruments or blades

safety risk, other

requirement of numeracy/literacy skills.

3.4. Face validation and refinement

As a result of the initial expert review, two skills, ‘Using a peeler’ and ‘Using a can opener’ were moved to the 9+ age range from 3 to 5 years and 7–9 years respectively due to the variability in the types of utensils required to perform the skill and the safety risks associated with performing the skills. One skill ‘Pouring from a container’ was moved to 5–7 years from 7 to 9 years range. The skill, ‘Scraping down a bowl,’ was removed due to its similarity with other included skills ‘Stirring and mixing’ and ‘Spooning’ and one skill ‘Sieving’ was re-added on the advice of experts, although it was mentioned less frequently in previous recommendations and thus removed at an earlier stage. An additional seven skills, ‘Kneading and mixing with hands,’ ‘Mashing,’ ‘Sprinkling and rubbing in,’ ‘Peeling with fingers,’ ‘Using a grater,’ ‘Using an Oven or microwave,’ and ‘Shaking liquids in a sealed contained,’ had inconsistent levels of agreement from the different experts. Therefore the study team kept these in their initial categories as determined by their motor skill classification.

Finally, a second international expert review resulted in three skills moved age range, ‘Crushing and Pounding’ and ‘Shaking liquids in a sealed container’ were moved from 7 to 9 years to the younger age range of 5–7 years old, ‘Squeezing’ was moved from 2 to 3 years to the 3–5 age range due to the dependency of the skill on the child’s strength. The other skills remained in their previously determined age ranges, with the understanding that the resulting outcome of performing the skill in certain age ranges may have an effect on the quality of the product produced and that performing that skill in the recommended age range was more for a tactile experience. Additionally some skills may require higher levels of supervision than others. It was also noted by a number of experts that performing a skill in a certain age range can be affected by a number of factors including experience and inter-child differences. The final age-appropriate cooking recommendations can be found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Proposed evidence-based age-appropriate cooking skills recommendations for children.

| No. | Age | Cooking Skill | Expert Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2–3 years | Washing Fruit and Vegetables | |

| 2 | Kneading and Mixing with Hands | More for tactile experience, quality questionable, possibly practice with a utensil | |

| 3 | Tearing | ||

| 4 | Using a Rolling Pin | ||

| 5 | Rolling Mixtures into Balls | ||

| 6 | Breaking Vegetables into Pieces | ||

|

7

8 9 |

3–5 years | Using a Cookie Cutter Stirring and Mixinga Mashing |

|

| 10 | Spooning | ||

| 11 | Cutting, Chopping and Slicingb | Extremely close supervision and dependant on what is being chopped, begin with child safe knives/plastic/ butter knives and easier food such as chopping herbs or bananas. With practice and increased age and strength, sharper knives can be introduced and food more difficult to chop such as carrots. | |

| 12 | Spreading and | ||

| 13 | Buttering Using Scissorsb |

||

| 14 | Brushing Oil on with a Pastry Brush | ||

| 15 | Sieving | ||

| 16 | Squeezing | ||

| 17 | 5–7 years | Sprinkling and Rubbing In | |

| 18 | Breading, Flouring and Dipping | ||

| 19 | Picking and Podding | ||

| 20 | Greasing | ||

|

21

22 |

Peeling with Fingers Skeweringb | ||

| 23 | Pouring from a container | ||

| 24 | Crushing and Pounding | ||

| 25 | Shaking Liquids in a Sealed Container | ||

|

26

27 |

7–9 years | Weighing and Measuringd Using a Graterb |

|

| 28 | Using an Oven or Microwavead | ||

|

29

30 |

Draining Using a Hand Mixerc |

||

|

31

32 |

9þ

years |

Using a Peeler Using a Can Opener Stirring and Mixing over Heat |

Child and prior cooking experience dependent |

| Using Sharp Scissors | Child and prior cooking experience dependent | ||

| Skewering Unsupervised Weighing and Measuring Unsupervised Using a Grater Unsupervised Using an Oven or Microwave Unsupervised |

Child and prior cooking experience dependent, perhaps at older ages | ||

| Using a Hand Mixer Unsupervised | Child and prior cooking experience dependent, perhaps at older ages |

Superscript letters represent cooking skills that may need to be considered in an older age range due to additional developmental requirements:

– safety risk, potential for burns

– safety risk, sharp instruments or blades

– safety risk, other

– requirement of numeracy/literacy skills.

4. Discussion

Cooking programmes are often criticised for the lack of rigour in their design and content development (Hersch et al., 2014; McGowan et al., 2017; Reicks et al., 2014, 2018). This may be due to the lack of guidance practitioners have when developing programmes. While guidance for programme design is being addressed (Asher et al., 2020), there is a need for information on the content pertaining to programmes. To the best of our knowledge, the proposed age-appropriate cooking recommendations for children are the first recommendations to be developed that are underpinned by scientific rationale and have undergone face validation. These recommendations should act as a reference point when designing cooking programmes to the appropriate age groups. Furthermore, they may offer guidance for parents and/or carers in a home environment on different cooking tasks they can include their children at different ages.

4.1. Classification of cooking skills into age ranges

When determining appropriate ages to assign to each motor skills group, it was necessary to note that fine motor skills develop and improve over a range of ages rather than appear and become perfected at a specific age (Dosman et al., 2012). Taking this into consideration, skills were assigned to an appropriate age based on when a child is expected to be fully capable of using the fine motor skills required to complete the skill, rather than at the age at which a fine motor skill first begins to develop. The ranges start from the age of 2 years old as by the age of 2 years a child should be able to follow basic commands from their parents and complete the tasks they are asked to do (Reilly et al., 2015). Some skills need further more complex developmental skills such as numeracy and literacy and were highlighted as possibly needing to be performed at older ages. The skill ‘Stirring and Mixing’ is often carried out over heat, for example, when stirring a pot that is heating on a stove top. This may not be safe for a 5-year-old child to do in case of burns and scalds and therefore if this skill were to be carried out over heat, it should be undertaken at a higher age. ‘Using Scissors,’ ‘Using a Peeler’ and ‘Cutting, Chopping and Slicing’ were highlighted for older children, because although younger children may be physically capable of using these utensils in terms of fine motor ability, they may hurt themselves if left unsupervised with the sharp blades. Therefore, adult supervision is advised for children when ‘Cutting, Chopping and Slicing.’ It is suggested that child safety knives or plastic knives are used in the beginning and easy food such as herbs that require little strength from the child should be used in the introduction to this skill to ensure the safety of the child. As the child increases proficiency in the skill through practice and with increased age and strength the sharpness of the knife can be increased or the type of food changed to harder foods such as vegetables. While exposure of young children to knives may cause fear, by introducing the child through safety/plastic knives, it allows the child to practice their technique and gain confidence and proficiency in performing the skill. This is in line with research around managing risk but not complete removal of risks needed for children’s healthy development (Brussoni et al., 2012; Niehues et al., 2015). However, older children may be more suited to these cooking skills if they are expected to work unsupervised. Alternatively, children could also be given ‘child-safe’ scissors or peelers which have less sharp blades. ‘Skewering’ was also highlighted for safety reasons. Children using skewers may injure themselves if the skewers are very sharp or if they are not shown how to correctly hold the skewers and ingredients. Because of this, children should be supervised whilst completing this task to ensure they do not hurt themselves or alternatively, this skill should be saved for older children who have greater safety awareness. ‘Weighing and Measuring’ was highlighted due to the need for some numeracy skills to complete this task. If a child at this age did not possess the numeracy skills required to accurately measure or weigh some ingredients, they may require assistance from an adult. ‘Using a Grater’ and ‘Using a Can Opener’ were highlighted due to the presence of the sharp blades on these pieces of equipment. Because of this, as well as the need for increased strength to use these pieces of equipment, older children may be more suited to these cooking skills if the child is expected to work unsupervised. ‘Using an Oven or Microwave’ was highlighted for several reasons as follows. Children will require some numeracy skills to correctly set times and temperatures. They will also require safety awareness as they will be working with hot dishes and must be reminded to wear heat-proof gloves. Particularly when using the oven, children must be careful not to burn themselves when reaching into the oven due to the extremely hot surfaces. ‘Using a Hand Mixer’ was highlighted as it is an electrical appliance. Children expected to use a hand mixer must be properly educated on electrical safety and be aware of any possible dangers when using the equipment, for example water or frayed wires. Children using a hand mixer must also be supervised to ensure they do not stick their fingers in the mixers as they could injure themselves if they did so. For these reasons, children using a hand mixer should be supervised or this skill should be carried out by older, more mature children.

The two-stage critical review by a number of multidisciplinary international experts provided face validation for the rigorously developed proposed recommendations. However, further research is needed to assess the veracity of the cooking skills with children in the different age ranges, for example what is seen as successful for a 3 year old ‘rolling a mixture into a ball’ may not be the same criteria for a 7 year old. Thus, some skills can be performed at certain ages, however, they are considered more for the tactile experience for the child, rather than the quality of the outcome. Further intricate studies measuring both motor skills and cooking skills are needed to develop criteria for the quality and accuracy of skill performance by age, especially as recent research suggests children may not be developing their motor skills at a normative rate (Gaul & Issartel, 2016). There is a need to investigate whether using cooking skills can act as a mechanism to enhance children’s motor skill development. Additionally, there are a number of factors that may affect a child’s fine motor skill development and thus their ability to perform different cooking skills. Higher socioeconomic status, better educated parents, having siblings and having a higher quality level of education from a young age are associated with greater rate of development of fine motor skills (Venetsanou & Kambas, 2009). As well as this, research into the effect of sex on motor skills, suggests that girls’ fine motor skills outperform boys’ at very young ages but older boys’ gross motor skills are greater than those of girls’ (Kokštejn et al., 2017). As ‘cooking’ tends to be seen as a gendered activity, the relationship between motor skill development and performing cooking skills may be a key area for further investigations.

4.2. Individual differences in children

In addition, the individual capacity of each child to perform a particular cooking skill must be considered. If a child’s motor coordination and/or strength to perform certain cooking skills is inadequate then these skills may need to be introduced at the higher end of the age range or in the next age range. A child’s interest in cooking may be another aspect that may impact on their willingness to perform certain skills. One strategy that promotes interest in cooking is the parents attitudes to cooking, as recent research suggests that parental perceptions around cooking, either positive or negative, is passed on to their children (Mazzonetto et al., 2020). Another situational aspect that needs to be considered, is where the child is learning the skill. If a child is apprehensive to try a new skill in the home environment, then, in a preschool/school environment they may be willing to attempt a skill through peer modelling to build their confidence. Peer modelling has been effectively used to improve learning in academic subjects (Topping, 2005).

4.3. Guidance

Subject to the above considerations, the proposed recommendations are intended to act as a guide for parents, teachers, and researchers when designing children’s cooking programmes or for any person with an interest in teaching children meal preparation skills. Parents have previously highlighted their apprehension and safety concerns about including children in cooking tasks in the kitchen (Lavelle et al., 2019). The proposed recommendations may reduce stress/anxiety of parents by guiding them towards appropriate tasks that could include their children. Additionally, secondary school Home Economic teachers have noted that they have to start from ‘scratch’ teaching adolescents basic practical food skills (Ronto et al., 2017). The proposed recommendations may assist primary school teachers interested in or already including elements of practical skills in their classrooms, to select age-appropriate cooking skills to be used with their students. Furthermore, the design of cooking skills programmes in both adults and children have been criticised (Hersch et al., 2014; McGowan et al., 2017). The proposed recommendations act as a guidance for the content development of children’s or parent-child cooking programmes and provide a rationale for the teaching of certain skills in different programmes. This will help to strengthen the design of cooking programmes helping to optimise their effectiveness.

4.4. Strengths and limitations

These are the first children’s cooking recommendations underpinned with scientific rationale and critically reviewed by a range of international experts. However, some limitations must be considered. The deconstruction of cooking skills and mapping to motor skills considered movements generally needed to perform a particular skill. However, the type of utensil used can have an impact on the quality or accuracy of the skill being performed, e.g. the type of can opener being used. This point was raised by the expert reviewers and in light of this some skills were moved to a higher age range. Thus, performing cooking skills that require the use of utensils may need further consideration depending on the specific utensil being used as this may impact on the quality of the outcome. In line with this, further research is required to understand the accuracy and quality of children performing the different skills in a particular age range. While every effort was made to gain an international perspective on children’s cooking recommendations, some cultural differences may still exist. Furthermore, while the above recommendations focus on the manual cooking skills, there are some other cooking related tasks that may be introduced to children in these age ranges, such as reading recipes. While reading recipes can be considered a complex task, simply written recipes may be introduced to children from younger age ranges depending on their numeracy and literacy levels.

5. Conclusions

Through a four stage process of development and validation, new evidence based, age-appropriate children’s cooking skills recommendations are proposed. They can act as guidance for parents and give them assurance to include their children to undertake different cooking related tasks in the kitchen. Additionally, the recommendations provide a rationale for content development in programme design to ensure the programmes are targeted at children at appropriate ages, which will strengthen the design of interventions in this research area optimising their effectiveness.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank all experts who took part in the critical review of the cooking skills recommendations.

Funding

This specific research received no external funding. JAW was supported by the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive And Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (Award #K01DK119166).

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required for this research, as human participants were not used in this research. The international experts acted in a consultation capacity in line with a scoping review (Tricco et al., 2016) and in line with other studies that included consultation activities for their results published in Elsevier journals (Elshahat et al., 2019).

References

- A Healthier Michigan. (2017). Available online: https://www.ahealthiermichigan.org/2017/11/21/age-guide-teaching-kids-healthy-cooking-skills. (Accessed 23 March 2019).

- Asher RC, Jakstas T, Wolfson JA, Rose AJ, Bucher T, Lavelle F, Dean M, Duncanson K, Innes B, Burrows T, & Collins CE (2020). Cook-EdTM: A model for planning, implementing and evaluating cooking programs to improve diet and health. Nutrients, 12, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BBC Good Food. Available online: https://www.bbcgoodfood.com/howto/guide/guide-cookery-skills-age (accessed on 24th March 2019).

- Brussoni M, Olsen LL, Pike I, & Sleet DA (2012). Risky play and children’s safety: Balancing priorities for optimal child development. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9, 3134–3148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Nutrition Studies. Available online: https://nutritionstudies.org/cooking-at-every-age-why-kids-should-learn-to-cook (accessed on 23rd March 2019).

- Cunningham-Sabo L, & Lohse B (2013). Cooking with Kids positively affects fourth graders’ vegetable preferences and attitudes and self-efficacy for food and cooking. Childhood Obesity, 9, 549–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Hondt V, Deforche B, Vaeyens R, Vandorpe B, Vandendriessche J, Pion J, Philippaerts R, De Bourdeaudhuij I, & Lenoir M (2011). Gross motor coordination in relation to weight status and age in 5-to 12-year-old boys and girls: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Pediatric Obesity, 6(sup3), e556–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosman CF, Andrews D, & Goulden KJ (2012). Evidence-based milestone ages as a framework for developmental surveillance. Paediatrics and Child Health, 17, 561–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eat Right. Available online https://www.eatright.org/homefoodsafety/four-steps/cook/teaching-kids-to-cook (accessed on 23rd March 2019).

- Eating Well. Available online: http://www.eatingwell.com/article/290725/cooking-skills-every-kid-should-learn-by-age-10/ (accessed on 23rd March 2019).

- Elshahat S, Woodside JV, & McKinley MC (2019). Meat thermometer usage amongst European and North American consumers: A scoping review. Food Control. [Google Scholar]

- Food Sorcery. Available online: https://www.foodsorcery.co.uk/age-children-learn-to-cook/ (accessed on 23rd March 2019).

- Fordyce-Voorham S (2011). Identification of essential food skills for skill-based healthful eating programs in secondary schools. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 43, 116–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallahue D, Ozmun J, & Goodway JD (2012). Understanding motor development: Infants, children, adolescents and adults (7th ed.). Boston, US: Mc Graw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Gaul D, & Issartel J (2016). Fine motor skill proficiency in typically developing children: On or off the maturation track? Human Movement Science, 46, 78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentier I, D’Hondt E, Shultz S, Deforche B, Augustijn M, Hoorne S, Verlaecke K, De Bourdeaudhuij I, & Lenoir M (2013). Fine and gross motor skills differ between healthy-weight and obese children. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34, 4043–4051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber RJ, Wilks T, & Erdie-Lalena C (2010). Developmental milestones: Motor development. Pediatrics in Review, 31, 267–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JC, Lawlor DA, & Kimm SY (2010). Childhood obesity. Lancet, 375, 1737–1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersch D, Perdue L, Ambroz T, & Boucher JL (2014). Peer reviewed: The impact of cooking classes on food-related preferences, attitudes, and behaviors of school-aged children: A systematic review of the evidence. 2003–2014. Prev Chronic Dis, 11, E193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoelscher DM, Kirk S, Ritchie L, Cunningham-Sabo L, & Academy Positions Committee. (2013). Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: Interventions for the prevention and treatment of pediatric overweight and obesity. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 113, 1375–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Kids Cook Monday. Available online: https://www.thekidscookmonday.org/kitchen-tasks-for-different-age-groups/ (accessed on 23rd March 2019).

- The Kitchn. Available online: https://www.thekitchn.com/how-young-kids-can-help-in-the-kitchen-a-list-of-activities-by-age-222692 (accessed on 24th March 2019).

- Kokštejn J, Musálek M, & Tufano JJ (2017). Are sex differences in fundamental motor skills uniform throughout the entire preschool period? PloS One, 12, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb DA (1984). Experiential learning: Exeriences as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, US: Prentice- hall. [Google Scholar]

- Laska MN, Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D, & Story M (2012). Does involvement in food preparation track from adolescence to young adulthood and is it associated with better dietary quality? Findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Public Health Nutrition, 15, 1150–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavelle F, Benson T, Hollywood L, Surgenor D, McCloat A, Mooney E, Caraher M, & Dean M (2019). Modern transference of domestic cooking skills. Nutrients, 11, 870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavelle F, McGowan L, Spence M, Caraher M, Raats MM, Hollywood L, McDowell D, McCloat A, Mooney E, & Dean M (2016b). Barriers and facilitators to cooking from ‘scratch’using basic or raw ingredients: A qualitative interview study. Appetite, 107, 383–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavelle F, Spence M, Hollywood L, McGowan L, Surgenor D, McCloat A, Mooney E, Caraher M, Raats M, & Dean M (2016a). Learning cooking skills at different ages: A cross-sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phy, 13, 119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein AH, & Ludwig DS (2010). Bring back home economics education. Jama, 303, 1857–1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr D, Cermak S, Cohn ES, & Henderson A (2003). Fine motor activities in head start and kindergarten classrooms. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 57, 550–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzonetto AC, Le Bourlegat IS, dos Santos JLG, Spence M, Dean M, & Fiates GMR (2020). Finding my own way in the kitchen from maternal influence and beyond–A grounded theory study based on Brazilian women’s life stories. Appetite. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloat A, & Caraher M (2019). An international review of second-level food education curriculum policy. Cambridge Journal of Education, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- McGowan L, Caraher M, Raats M, Lavelle F, Hollywood L, McDowell D, Spence M, McCloat A, Mooney E, & Dean M (2017). Domestic cooking and food skills: A review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 57, 2412–2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metroparent. Available online: https://www.metroparent.com/daily/food-home/cooking-tips-nutrition/basic-cooking-skills-for-kids-at-every-age/ (accessed on 23rd March 2019).

- Mills S, Brown H, Wrieden W, White M, & Adams J (2017). Frequency of eating home cooked meals and potential benefits for diet and health: Cross-sectional analysis of a population-based cohort study. Int J Behav Nutr Phy, 14, 109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOMables. Available online: https://www.momables.com/teach-your-kid-how-to-cook-by-age/ (accessed on 23rd March 2019).

- National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/wecan/downloads/cookwithchildren.pdf (accessed on 23rd March 2019).

- Nelson SA, Corbin MA, & Nickols-Richardson SM (2013). A call for culinary skills education in childhood obesity-prevention interventions: Current status and peer influences. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 113, 1031–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NewsOk. Available online: https://newsok.com/article/5606765/when-should-kids-start-helping-in-the-kitchen-now-is-good (accessed on 24th March 2019).

- Niehues AN, Bundy A, Broom A, & Tranter P (2015). Parents’ perceptions of risk and the influence on children’s everyday activities. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 809–820. [Google Scholar]

- The official website of the government of Canada. Available online: https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/healthy-eating-recommendations/cook-more-often/involve-others-in-planning-and-preparing-meals/involving-kids-in-planning-and-preparing-meals/?wbdisable=true (accessed on 23rd March 2019).

- Okely AD, Booth ML, & Chey T (2004). Relationships between body composition and fundamental movement skills among children and adolescents. Research Quarterly for Exercise & Sport, 75, 238–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oregon Live. Available online: https://www.oregonlive.com/cooking/2018/06/cooking_with_kids.html (accessed on 23rd March 2019).

- Pandita A, Sharma D, Pandita D, Pawar S, Tariq M, & Kaul A (2016). Childhood obesity: Prevention is better than cure. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy, 9, 83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne G, & Isaacs LD (2017). Human motor development: A lifespan approach. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Reicks M, Kocher M, & Reeder J (2018). Impact of cooking and home food preparation interventions among adults: A systematic review (2011–2016). Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 50, 148–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reicks M, Trofholz AC, Stang JS, & Laska MN (2014). Impact of cooking and home food preparation interventions among adults: Outcomes and implications for future programs. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 46, 259–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly S, McKean C, Morgan A, & Wake M (2015). Identifying and managing common childhood language and speech impairments. BMJ, 350, h2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronto R, Ball L, Pendergast D, & Harris N (2017). Environmental factors of food literacy in Australian high schools: Views of home economics teachers. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 41, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom L, & Horton ME (1971). The maturation of fine prehension in young children. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 13, 3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo K, Sahoo B, Choudhury AK, Sofi NY, Kumar R, & Bhadoria AS (2015). Childhood obesity: Causes and consequences. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 4, 187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater J (2013). Is cooking dead? The state of home economics food and nutrition education in a Canadian province. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 37, 617–624. [Google Scholar]

- Taste of Home. Available online: https://www.tasteofhome.com/article/cooking-with-kids-a-guide-to-kitchen-tasks-for-every-age/ (accessed on 23rd March 2019).

- Topping KJ (2005). Trends in peer learning. Educ Psychol, 25, 631–645. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien K, Colquhoun H, Kastner M, Levac D, Ng C, Sharpe JP, Wilson K, & Kenny M (2016). A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC medical research methodology, 16(1), 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venetsanou F, & Kambas A (2009). Environmental factors affecting preschoolers’ motor development. Early Childhood Education Journal, 37, 319–327. [Google Scholar]

- Vidgen HA, & Gallegos D (2014). Defining food literacy and its components. Appetite, 76, 50–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WebMD. Available online: https://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/features/cooking-with-your-children (accessed on 24th March 2019).

- Wolfson JA, Bostic S, Lahne J, Morgan C, Henley SC, Harvey J, & Trubek A (2017). A comprehensive approach to understanding cooking behavior. British Food Journal, 119, 1147–1158. [Google Scholar]

- The Works. Available online: https://blog.theworks.co.uk/2016/04/life-skills-kids-cooking/ (accessed on 23rd March 2019).

- World Health Organization. (2016). Report of the commission on ending childhood obesity. Geneva: WHO. Available online: http://www.who.int/end-childhood-obesity/publications/echo-report/en/. (Accessed 17 December 2019). [Google Scholar]