Abstract

A library of natural products and their derivatives was screened for inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) 1B, which is a validated drug target for the treatment of obesity and type II diabetes. Of those active in the preliminary assay, the most promising was compound 2 containing a novel pyrrolopyrazoloisoquino-lone scaffold derived by treating radicicol (1) with hydrazine. This nitrogen-atom augmented radicicol derivative was found to be PTP1B selective relative to other highly homologous nonreceptor PTPs. Biochemical evaluation, molecular docking, and mutagenesis revealed 2 to be an allosteric inhibitor of PTP1B with a submicromolar Ki. Cellular analyses using C2C12 myoblasts indicated that 2 restored insulin signaling and increased glucose uptake.

Protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) and kinases (PTKs) are signaling enzymes that modulate phosphorylation of proteins and play crucial roles in many essential cellular pathways including mitosis, metabolic regulation, cell proliferation, and apoptosis.1 PTKs catalyze the phosphorylation of tyrosine residues of proteins while PTPs reverse this action by hydrolyzing the tyrosine phosphate. This addition/subtraction mechanism allows for careful regulation of cellular signaling events. Because of their critical biological functions, both the PTKs and PTPs have been pursued as drug targets for a variety of pathologic states including diabetes, cancer, and neurological and immune disorders.2 However, to date, only molecules targeting PTKs have entered the clinic,3 but discovery of clinically viable PTP modulators remains an area of active research.4

The nonreceptor PTP family member, PTP1B, is a validated target for the treatment of diabetes and obesity.5 PTP1B is ubiquitously expressed in the cytoplasm of all cells and localizes to the outer face of the endoplasmic reticulum.6 PTP1B-mediated dephosphorylation inactivates both the insulin and leptin signaling pathways.7 In the case of insulin signaling, PTP1B dephosphorylates the active insulin receptor (IR) and its downstream targets including insulin receptor substrates 1, 2, and 3.8 In leptin signaling, PTP1B antagonizes JAK2 activity,9 which is immediately downstream of the leptin receptor (ObR). PTP1B is therefore a negative regulator of both the insulin and leptin signaling pathways, interfering with both lipid and glucose homeostasis. In addition, PTP1B levels have been shown to be increased in patients with metabolic syndrome.10 Genetic ablation of PTPN1, the gene encoding PTP1B, leads to an increase in insulin sensitivity and resistance to obesity in animal models on a high fat diet.11

Many proteins that are desirable drug targets remain without viable clinical leads because they are “undruggable”.12 This can be due to a variety of reasons, but in the case of PTP1B, this is because of a charged, shallow active site that is conserved among all PTPs.13 Although the issue of active site selectivity has been addressed through the use of complex synthetic molecules,1b,14 often these molecules suffer from poor pharmacological properties.15 Roadblocks to human trials with previously discovered molecules have arisen primarily due to lack of PTP1B specificity and/or poor pharmacology. Allosteric inhibitors are an attractive alternative to active site inhibitors, as allosteric sites vary across PTPs, giving heightened selectivity, and these sites are potentially more druggable than the active site. This approach was employed by Wiesmann et al. in 2004, who reported the PTP1B inhibitory activity of benzofuran derivatives. These molecules were shown to bind to a hydrophobic pocket, discovered through X-ray crystallography, located ~20 Å from the active site.16 Computational studies suggest that these derivatives keep PTP1B in an inactive state, in which the WPD loop (a conserved loop in PTPs essential for activity) is in an open conformation, by interrupting the triangular interaction among helix 7α, helix 3α, and loop 11.17 Other approaches have also been employed to tackle the inherent difficulties of drugging PTP1B. Krishnan et al. recently identified trodusquemine, also known as MSI-1436, which targets the disordered C-terminus of PTP1B.18 In addition, there has been a flurry of publications reporting both natural product and synthetic small-molecule PTP1B inhibitors.14,19 While these results show encouraging progress and offer critical insight into PTP1B as a viable therapeutic target, more isoform-selective PTP1B inhibitors with improved pharmacological properties and enhanced potency are still needed, since a clinically effective drug targeting PTP1B has yet to be discovered.

Natural products constitute a rich source of biologically active molecules.20 Many of the drugs that are available on the market either mimic naturally occurring molecules or consist of structures that are fully or in part taken from such natural motifs.21 The value of natural products as platforms for developing front-line drugs is in part due to the fact that their chemical diversity is complementary or superior to that found in synthetic libraries. It is noteworthy that compared with synthetic and combinatorial counterparts, natural products are stereochemically more complex and have a broader diversity of ring systems, structural features that have resulted from a long evolutionary selection process.22 However, less than 20% of the ring systems found in natural products are represented in current commercial drugs;23 whereas drugs and combinatorial molecules contain a higher number of heteroatom-containing groups and/or ring systems.24 In continuing our work on structural diversification of natural products,25 we have recently utilized a chemical strategy involving hydrazine-mediated nitrogen (N)-atom augmentation of carbonyl compounds abundant in nature to obtain more druglike compounds.26 Generation of natural product-like compound libraries by chemical modification of compounds in complex natural mixtures of unknown composition has been described previously.27

In an effort to discover isoform selective PTP inhibitors, we cloned, expressed, and purified a panel of highly conserved nonreceptor PTPs. Using this panel, we screened a small library (500 members) of natural products and their N-atom augmented derivatives using a well characterized p-nitrophenol phosphate (pNPP) assay28 with a Z-factor >0.8 (Supporting Information, Table S1). The library was made up of purified marine and terrestrial natural products with diverse scaffolds in addition to a much smaller subset of derivatized natural products. From this screen, we found 14 hits that were reconfirmed in triplicate and in dose−response giving an ~2.8% hit rate. Four of the hits were from our N-atom augmented compounds. Interestingly, of those tested, the most promising, based on both potency and specificity, was the dihydropyrrolopyrazoloisoqionolone (2) resulting from N-atom augmentation of the well-known HSP90 inhibitor, radicicol (1) (Scheme 1). Reaction of the macrocyclic benezenediol lactone, radicicol (1) with hydrazine hydrate in EtOH afforded a mixture of N-augmented analogues 2−5 containing a hitherto unprecedented carbon skeleton (Scheme 1). The structures of compounds 2−5 were characterized by extensive NMR analysis (see discussion in the Supporting Information; pages S6 and S7, Figures S1–S24). However, compound 2 could be isolated as the major product in 71% yield if the reaction was conducted for 16 h exposed to air. In this case, the reduction of 3 leading to 2 is probably mediated by hydrazine.29 Compound 2 could also be accessed indirectly by Pd/C-catalyzed hydrogenation of 3 in quantitative yield (Scheme 1). The structure of 2 was unambiguously confirmed by X-ray crystallography (Figure 1; CCDC: 1880627). Aiming to improve the bioactivity of radicicol (1), attempts to modify its structure have previously drawn attention. However, all of the efforts have focused on finding more druglike HSP90 inhibitors and have left the core structure unchanged.30 By contrast, we completely reshaped radicicol (1) with simple hydrazine treatment and shifted the bioactivity from HSP90 to PTP1B.

Scheme 1.

N-Atom Augmentation of Radicicol (1) Resulting in Compounds 2, 3, 4, and 5

Figure 1.

X-ray crystallographic structure of 2, showing displacement ellipsoid plots (50% probability).

We propose the formation of compounds 2−5 begins with the Michael addition of hydrazine to radicicol (1), leading to intermediate A. Then A can undergo an intramolecular transesterification affording B. Intermediate B could be transformed to intermediate C through hydrazinolysis of the lactone. An SN2 attack of the epoxide by hydrazine, resulting in the reversal of the absolute configuration at the reactive carbon center, would lead to intermediate D. Subsequently, the tetracyclic compound 5 can be generated via hydrazine addition to the ketone. Elimination of water from 5 would provide compounds 3 and 4. Compound 3 was likely reduced by another equivalent of hydrazine to furnish compound 2 (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Proposed Mechanism for the Formation of 2, 3, 4, and 5 from Radicicol Treated with Hydrazine Hydrate

Compound 2 was found to inhibit PTP1B with very good to excellent selectivity versus six other nonreceptor PTPs (for SDS-PAGE of PTPs see the Supporting Information, Figure S25). These hits were confirmed in triplicate, and then a 10-point dose−response was carried out to determine the IC50 values for each compound. Once validated as bona fide PTP1B inhibitors, the IC50 values relative to the other PTPs used in the initial screen were also measured. Compound 2 showed >10-fold selectivity for PTP1B relative to TCPTP, which shares 70% structural identity with PTP1B, and is considered the greatest off-target liability. SHP1 was the other PTP inhibited by 2, but there was >5-fold selectivity. For each of the other PTPs, 2 showed >20-fold selectivity (Figure 2a and Figures S26–S28). In order to determine the mechanism of inhibition and perhaps gain insight into the source of the selectivity, an enzymological evaluation was carried out by varying the concentrations of substrate and inhibitor and measuring the initial rates. Based on the Dixon plot of these data, 2 showed mixed inhibition of PTP1B with Ki = 0.43 ± 0.15 μM (Figure 2b). Mixed inhibition is indicative of an allosteric mechanism of inhibition.

Figure 2.

Compound 2 is an isoform-selective PTP1B inhibitor. (a) Relative IC50 values of 2 for PTPs normalized to PTP1B IC50 value (* relative IC50 values >20); (b) Dixon plot for PTP1B showing 1/rate versus varying concentrations of compound 2 at p-NPP concentrations of 1 mM (black dots), 2 mM (blue dots), 2.5 mM (green dots), and 3 mM (red dots). The x-coordinate of the intersection point gives a Ki of 0.43 ± 0.15 μM. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

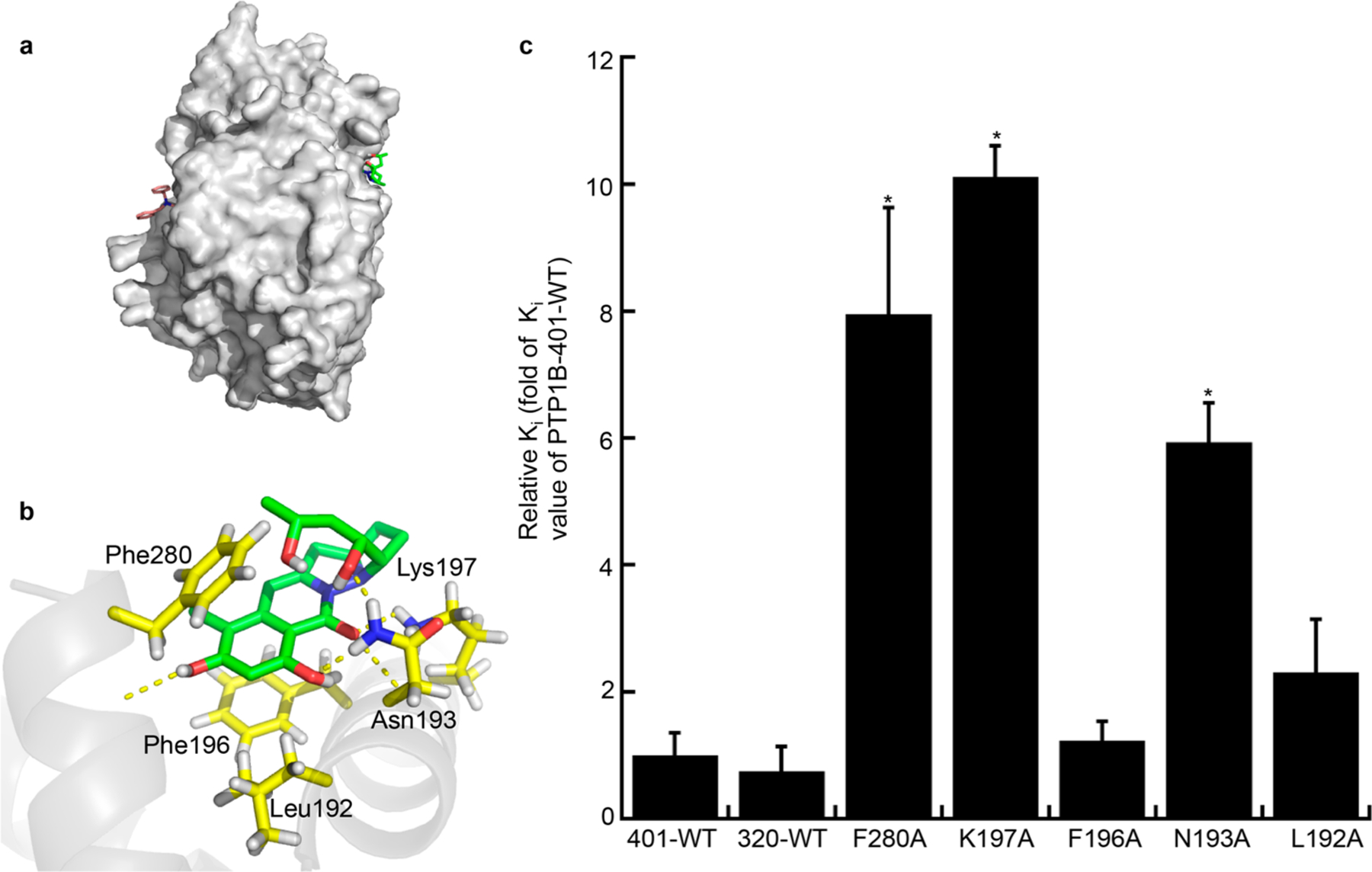

Next, to gain insight into the structural details of PTP1B inhibition, molecular docking experiments were performed on 2 (CCDC 1880627) and PTP1B (1T4J) with Autodock 4.2.31 By comparing to an aryl diketoacid derivative, a known competitive inhibitor that binds to the active site of PTP1B, we could see compound 2 docked to a reported allosteric site of PTP1B (Figure 3a).32 Based on these docking results, five residues were predicted to interact with 2 (Figure 3b). Of these five, F280, F196, and L192 were predicted to produce stacking interactions with compound 2, while K197 and N193 were predicted to form hydrogen bonds with the phenolic hydroxy groups, the carbonyl group of the amide, and the two hydroxy groups on the aliphatic side chain. To test the derived computational model, a C-terminal truncation of PTP1B-WT1–320, containing the first 320 amino acids, and five alanine mutants were constructed through site-directed mutagenesis.33 The Ki of compound 2 against each of these PTP1B variants was measured (Supporting Information, Figures S29–S34 and Table S2). As shown in Figure 3c, there is no statistically significant inhibitory difference between PTP1B-WT1−320 and PTP1B-WT1−401, indicating that compound 2 does not bind to the C-terminus of PTP1B. Three of the mutants tested, F280A, K197A, and N193A, were observed to have Ki values which were 8, 10, and 6-fold less potent, respectively. Therefore, these data support that compound 2 binds to this allosteric site and these three residues participate in the interaction. The other two mutants, F196A and L192A, did not cause a statistically significant increase in Ki values. This can potentially be explained by the docking model which shows residues F196 and L192 pointing away from the ligand. Presently, we cannot rule out a severe structural perturbation caused by these mutations that leads to rearrangement of a distal pocket,34 but our differential scanning calorimetry shows no loss of protein stability (Supporting Information, Figure S35) and we observe no deleterious effects to biochemical function based on hydrolysis of p-NPP.

Figure 3.

Molecular modeling of the binding of compound 2 to PTP1B. (a) Surface structure of PTP1B generated in pymol showed a predicted allosteric binding pocket of compound 2 (green, PDB ID 1T4J) and a known active site binding aryl diketo acid derivative (blue, PDB ID 3eb1). (b) Close up of specific interactions predicted between PTP1B and compound 2. (c) Mutations in the predicted compound 2 binding site of PTP1B compromise its inhibitory activity. The Ki values of each mutant and PTP1B-WT1−320 challenged with compound 2 are shown relative to PTP1B-WT1−401. * P < 0.05.

Subsequently, we tested the cellular activity of compound 2. Immunoblot analyses were performed to detect changes in insulin signaling upon stimulation of C2C12 myotubes treated with 0.5, 25, or 50 μM 2. This was accomplished by assessing the phosphorylation state of IR and AKT with phospho-protein specific antibodies. DMSO and sodium orthovanadate were used as vehicle and positive controls, respectively.35 As presented in Figure 4a, the phosphorylation levels of IR and AKT increase in a dose-dependent manner after treatment with 2. These data corroborate our biochemical data and argue that PTP1B is a cellular target of 2. Moreover, given 2 is semisynthetic, it is an attractive lead that can be optimized through medicinal chemistry efforts. We next asked if the effect of 2 on the insulin pathway resulted in increased glucose uptake in C2C12 cells. To answer this question, we treated differentiated C2C12 cells with 2, DMSO (NC), 200 nM insulin (PC), and used 2-(N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino)-2-deoxyglucose (2-NBDG) to evaluate the glucose uptake level of the treated cells. 2-NBDG is a fluorescent glucose mimetic that allows for quantitation of cellular glucose uptake without using a radioisotope.36 We observed an increase in glucose uptake with as little as 10 μM compound 2, and the increase was ~5-fold at 100 μM compound 2 (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

(a) Compound 2 increases insulin signaling in C2C12 myotubes in a dose-dependent manner. C2C12 myotubes were treated with 0.5 μM, 25 μM, and 50 μM compound 2, DMSO (NC), and 20 μM sodium orthovanadate (PC) for 6 h. Then cells were stimulated with 10 nM insulin for 10 min. The lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with indicated antibodies. (b) Compound 2 increases glucose uptake in differentiated C2C12 myotubes in a dose-dependent manner. Differentiated C2C12 myotubes were treated with 0.1 μM, 1 μM, 10 μM, and 100 μM compound 2, DMSO (vehicle control), and 200 nM insulin (positive control) for 6 h. The cells were then treated with 200 μM 2-NBDG for 24 h and then stimulated with 10 nM insulin for 2 h. 2-NBDG was detected at Ex/Em = 485/535 nm. *P < 0.05.

In conclusion, we report a PTP1B inhibitor with very good to excellent isoform selectivity relative to other highly similar nonreceptor PTPs. The promising compound was derived from our N-atom augmentation strategy of the HSP90 inhibitor, radicicol (1). Based on molecular docking experiments, mutagenesis, and enzymological evaluation, this inhibitor is predicted to bind to a previously described allosteric site of PTP1B. The computational model was tested by measuring the Ki of alanine mutants of PTP1B and C-terminally truncated PTP1B. The results showed that the C-terminus was not the binding site of 2, whereas F280, K197, and N193 were likely involved in the binding interaction. The cellular activity of the inhibitor was evaluated in insulin-stimulated C2C12 myotube cells. Treatment with compound 2 resulted in upregulation of insulin signaling and ultimately glucose uptake in a dose-dependent manner. To advance 2 toward a more viable clinical lead and to understand the details of binding, we have initiated structural investigations. These will be used to inform future medicinal chemical optimization of 2. The structure of 2 suggests that it can be readily modified at several positions for the optimization of potency and selectivity. In addition, we will evaluate an optimized analogue of 2 in a series of murine models of obesity and diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Funding

Financial support for this work was provided by Grant R01 CA090265 funded by the NCI and Grant P41 GM094060 funded by the NIGMS. We acknowledge the China Scholarship Council and the NIH T32 Training Grant GM008804 to A.J.A.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.biochem.9b00499.

Experimental procedures, analytical data (1H and 13C NMR, HRMS, IR, [α]D), and biological activity (PDF) Crystallographic data for 2 (CIF)

Accession Codes

The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre: CCDC entry 1880627 for 2. PTP1B-WT1 – 401, SPIN200017113; PTP1B-WT1–320, SPIN200017103; PTP1B-A280A1–401, SPIN200017108; PTP1B-K197A1–401, SPIN200017118; PTP1B-F196A1–401, SPIN200017113; PTP1B-N193A1–401, SPIN200017123; PTP1B-L192A1–401, SPIN200017128.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Tonks NK (2006) Protein tyrosine phosphatases: from genes, to function, to disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 7, 833–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang S, and Zhang Z-Y (2007) PTP1B as a drug target: recent developments in PTP1B inhibitor discovery. Drug Discovery Today 12, 373–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Alonso A, Sasin J, Bottini N, Friedberg I, Friedberg I, Osterman A, Godzik A, Hunter T, Dixon J, and Mustelin T (2004) Protein tyrosine phosphatases in the human genome. Cell 117, 699–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Andersen JN, Jansen PG, Echwald SM, Mortensen OH, Fukada T, Del Vecchio R, Tonks NK, and Møller NPH (2004) A genomic perspective on protein tyrosine phosphatases: gene structure, pseudogenes, and genetic disease linkage. FASEB J. 18, 8–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Bialy L, and Waldmann H (2005) Inhibitors of protein tyrosine phosphatases: next-generation drugs? Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 44, 3814–3839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Levitzki A (2013) Tyrosine kinase inhibitors: views of selectivity, sensitivity, and clinical performance. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol 53, 161–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) Carr G, Berrue F, Klaiklay S, Pelletier I, Landry M, and Kerr R-G (2014) Natural products with protein tyrosine phosphatase inhibitory activity. Methods 65, 229–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yu Z-H, and Zhang Z-Y (2018) Regulatory Mechanisms and Novel Therapeutic Targeting Strategies for Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases. Chem. Rev 118, 1069–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Huang YD, Zhang YF, Ge LL, Lin Y, and Kwok HF (2018) The Roles of Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers 10, 82–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Zhang Z-Y, and Lee S-Y (2003) PTP1B inhibitors as potential therapeutics in the treatment of type 2 diabetes and obesity. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs 12, 223–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Goldstein BJ (2001) Protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B): a novel therapeutic target for type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity and related states of insulin resistance. Curr. Drug Targets: Immune, Endocr. Metab. Disord 1, 265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Krishnan N, Konidaris KF, Gasser G, and Tonks NK (2018) A (2018) potent, selective, and orally bioavailable inhibitor of the protein-tyrosine phosphatase PTP1B improves insulin and leptin signaling in animal models. J. Biol. Chem 293, 1517–1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Barford D, Flint AJ, and Tonks NK (1994) Crystal structure of human protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B. Science 263, 1397–1404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) Zhang Z-Y, Dodd GT, and Tiganis T (2015) Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases in Hypothalamic Insulin and Leptin Signaling. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 36, 661–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chiarreotto-Ropelle EC, Pauli LS, Katashima CK, Pimentel GD, Picardi PK, Silva VR, de Souza CT, Prada PO, Cintra DE, Carvalheira JB, Ropelle ER, and Pauli JR (2013) Acute exercise suppresses hypothalamic PTP1B protein level and improves insulin and leptin signaling in obese rats. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab 305, E649–E659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).(a) Johnson TO, Ermolieff J, and Jirousek MR (2002) Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibitors for diabetes. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 1, 696–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ostman A, and Böhmer FD (2001) Regulation of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling by protein tyrosine phosphatases. Trends Cell Biol. 11, 258–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Cheng A, Dubé N, Gu F, and Tremblay ML (2002) Coordinated action of protein tyrosine phosphatases in insulin signal transduction. Eur. J. Biochem 269, 1050–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).(a) Zabolotny JM, Bence-Hanulec KK, Stricker-Krongrad A, Haj F, Wang Y, Minokoshi Y, Kim YB, Elmquist JK, Tartaglia LA, Kahn BB, and Neel BG (2002) PTP1B regulates leptin signal transduction in vivo. Dev. Cell 2, 489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cook WS, and Unger RH (2002) Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B: a potential leptin resistance factor of obesity. Dev. Cell 2, 385–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Wu X, Hoffstedt J, Deeb W, Singh R, Sedkova N, Zilbering A, Zhu L, Park PK, Arner P, and Goldstein BJ (2001) Depot-specific variation in protein-tyrosine phosphatase activities in human omental and subcutaneous adipose tissue: a potential contribution to differential insulin sensitivity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 86, 5973–5980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).(a) Elchebly M, Payette P, Michaliszyn E, Cromlish W, Collins S, Loy AL, Normandin D, Cheng A, Himms-Hagen J, and Chan CC (1999) Increased insulin sensitivity and obesity resistance in mice lacking the protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B gene. Science 283, 1544–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Klaman LD, Boss O, Peroni OD, Kim JK, Martino JL, Zabolotny JM, Moghal N, Lubkin M, Kim Y-B, Sharpe AH, Stricker-Krongrad A, Shulman GI, Neel BG, and Kahn BB (2000) Increased energy expenditure, decreased adiposity, and tissue-specific insulin sensitivity in protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B-deficient mice. Mol. Cell. Biol 20, 5479–5489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Cheng A, Uetani N, Simoncic PD, Chaubey VP, Lee-Loy A, McGlade CJ, Kennedy BP, and Tremblay ML (2002) Attenuation of leptin action and regulation of obesity by protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B. Dev. Cell 2, 497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Perola E, Herman L, and Weiss J (2012) Development of a rule-based method for the assessment of protein druggability. J. Chem. Inf. Model 52, 1027–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Barr AL, Ugochukwu E, Lee WH, King ON, Filippakopoulos P, Alfano I, Savitsky P, Burgess-Brown NA, Müller S, and Knapp S (2009) Large-Scale Structural Analysis of the Classical Human Protein Tyrosine Phosphatome. Cell 136, 352–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Wang L-J, Jiang B, Wu N, Wang S-Y, and Shi D-Y (2015) Natural and semisynthetic protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) inhibitors as anti-diabetic agents. RSC Adv. 5, 48822–48834. [Google Scholar]

- (15).(a) Ma Y, Sun SX, Cheng XC, Wang SQ, Dong WL, Wang RL, and Xu WR (2013) Design and synthesis of imidazolidine-2,4-dione derivatives as selective inhibitors by targeting protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B over T-cell protein tyrosine phosphatase. Chem. Biol. Drug Des 82, 595–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sun JP, Fedorov AA, Lee SY, Guo XL, Shen K, Lawrence DS, Almo SC, and Zhang Z-Y (2003) Crystal structure of PTP1B complexed with a potent and selective bidentate inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem 278, 12406–12414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Wiesmann C, Barr KJ, Kung J, Zhu J, Erlanson DA, Shen W, Fahr BJ, Zhong M, Taylor L, Randal M, McDowell RS, and Hansen SK (2004) Allosteric inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 11, 730–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Li S, Zhang J, Lu S, Huang W, Geng L, Shen Q, and Zhang J (2014) The mechanism of allosteric inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B. PLoS One 9, e97668–e97677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Krishnan N, Koveal D, Miller DH, Xue B, Akshinthala SD, Kragelj J, Jensen MR, Gauss C-M, Page R, Blackledge M, Muthuswamy SK, Peti W, and Tonks NK (2014) Targeting the disordered C terminus of PTP1B with an allosteric inhibitor. Nat. Chem. Biol 10, 558–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).(a) Nören-Müller A, Reis-Corrêa I Jr., Prinz H, Rosenbaum C, Saxena K, Schwalbe HJ, Vestweber D, Cagna G, Schunk S, Schwarz O, Schiewe H, and Waldmann H (2006) Discovery of protein phosphatase inhibitor classes by biology-oriented synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 103, 10606–10611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Haftchenary S, Jouk AO, Aubry I, Lewis AM, Landry M, Ball DP, Shouksmith AE, Collins CV, Tremblay ML, and Gunning PT (2015) Identification of Bidentate Salicylic Acid Inhibitors of PTP1B. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 6, 982–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhou Y, Zhang W, Liu X, Yu H, Lu X, and Jiao B (2017) Inhibitors of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B from marine natural products. Chem. Biodiversity 14, e1600462–e1600473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Lawrence RN (1999) Rediscovering natural product biodiversity. Drug Discovery Today 4, 449–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).(a) Cragg GM, Newman DJ, and Snader KM (1997) Natural products in drug discovery and development. J. Nat. Prod 60, 52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kolb VM (1998) Biomimicry as a basis for drug discovery. Prog. Drug. Res 51, 185–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Grabley S, and Thiericke R (1999) Bioactive agents from natural sources: trends in discovery and application. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol 64, 101–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).O’Connell D, Jones S, Molloy S, and Amoils S (2005) In this issue. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 3, 905. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Clardy J, and Walsh C (2004) Lessons from natural molecules. Nature 432, 829–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Roveda J-G, Clavette C, Hunt AD, Gorelsky SI, Whipp CJ, and Beauchemin AM (2009) Hydrazides as tunable reagents for alkene hydroamination and aminocarbonylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 131, 8740–8741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).(a) Paranagama PA, Wijeratne EMK, and Gunatilaka AAL (2007) Uncovering Biosynthetic Potential of Plant-Associated Fungi: Effect of Culture Conditions on Metabolite Production by Paraphaeosphaeria quadriseptata and Chaetomium chiversii. J. Nat. Prod 70, 1939–1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wijeratne EMK, Bashyal BP, Gunatilaka MK, Arnold AA, and Gunatilaka AAL (2010) Maximizing chemical diversity of fungal metabolites: biogenetically related Heptaketides of the endolichenic fungus Corynespora sp. (1). J. Nat. Prod 73, 1156–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Wijeratne EMK, and Gunatilaka AAL Nitrogen-atom augmentation of natural products to generate drug-like molecules. Bioorg. Med. Chem, submitted. [Google Scholar]

- (27).López SN, Ramallo IA, Sierra MG, Zacchino SA, and Furlan RLE (2007) Chemically engineered extracts as an alternative source of bioactive natural product-like compounds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 104, 441–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Takai A, and Mieskes G (1991) Inhibitory effect of okadaic acid on the p-nitrophenyl phosphate phosphatase activity of protein phosphatases. Biochem. J 275, 233–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Espinosa JC, Navalon S, Alvaro M, Dhakshinamoorthy A, and Garcia H (2018) Reduction of C=C double bonds by hydrazine using active carbons as metal-free catalysts. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng 6, 5607–5614. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Agatsuma T, Ogawa H, Akasaka K, Asai A, Yamashita Y, Mizukami T, Akinaga S, and Saitoh Y (2002) Halohydrin and oxime derivatives of radicicol: synthesis and antitumor activities. Bioorg. Med. Chem 10, 3445–3454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ikuina Y, Amishiro N, Miyata M, Narumi H, Ogawa H, Akiyama T, Shiotsu Y, Akinaga S, and Murakata C (2003) Synthesis and antitumor activity of novel O-carbamoylmethyloxime derivatives of radicicol. J. Med. Chem 46, 2534–2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Shinonaga H, Noguchi T, Ikeda A, Aoki M, Fujimoto N, and Kawashima A (2009) Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of radicicol derivatives and WNT-5A expression inhibitory activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem 17, 4622–4635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Goodsell DS, and Olson AJ (2009) AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem 30 (16), 2785–2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Liu S, Zeng LF, Wu L, Yu X, Xue T, Gunawan AM, Long YQ, and Zhang Z-Y (2008) Targeting inactive enzyme conformation: aryl diketoacid derivatives as a new class of PTP1B inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc 130, 17075–17084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Bachman J (2013) Site-directed mutagenesis. Methods Enzymol. 529, 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Choy MS, Li Y, Machado ESF, Kunze MBA, Connors CR, Wei X, Lindorff-Larsen K, Page R, and Peti W (2017) Conformational rigidity and protein dynamics at distinct timescales regulate PTP1B activity and allostery. Mol. Cell 65, 644–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Martin KR, Narang P, Xu Y, Kauffman AL, Petit J, Xu HE, Meurice N, and MacKeigan JP (2012) Identification of Small Molecule Inhibitors of PTPσ through an Integrative Virtual and Biochemical Approach. PLoS One 7, e50217–e50224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Zou C, wang Y, and Shen Z (2005) 2-NBDG as a fluorescent indicator for direct glucose uptake measurement. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 64, 207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.