Abstract

Introduction

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is a disabling mental disorder characterized by excessive preoccupation with appearance. Trying to fix imagined defects many individuals with BDD search for aesthetic dermatology treatments. Due to omitting preliminary evaluation for BDD in subjects undergoing cosmetic procedures and lack of proper diagnostic tools among this group of individuals, the results of such interventions may face their disapproval and disappointment.

Aim

To translate and validate the Polish version of a Cosmetic Procedure Screening Questionnaire (COPS), which can be used in a cosmetic procedure setting to screen patients suspected to be suffering from BDD.

Material and methods

Both forward and backward translations of the original English version of the questionnaire to Polish were performed in accordance with international standards. The validation was conducted on 33 individuals undergoing aesthetic procedures, who completed the questionnaire twice with 3–6 days’ interval. Moreover, the subjects were also asked to fill the Polish versions of BIQLI (Body Image Quality of Life Inventory) and HADS (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) for convergent validity procedure.

Results

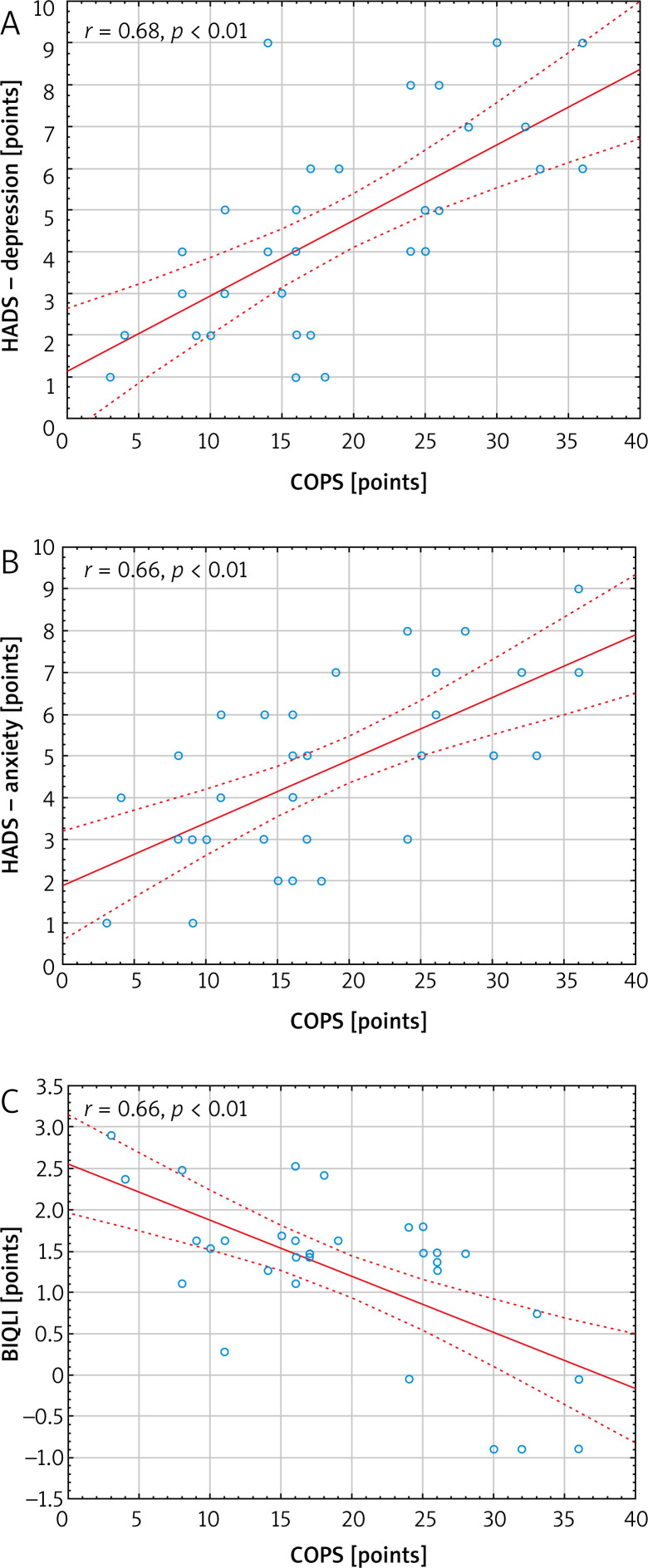

The Polish version of COPS demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach α coefficient value of 0.76) and reproducibility (Intraclass Correlation Coefficient, ICC, of 0.79). COPS correlated strongly with BIQLI (r = –0.66, p < 0.01) as well as with HADS, in both depression and anxiety subscales (r = 0.68, p < 0.01 and r = 0.66, p < 0.01, respectively).

Conclusions

The Polish version of the COPS questionnaire showed sufficient internal consistency and reliability. It can be used for BDD screening among the Polish speaking subjects undergoing aesthetic dermatology procedures.

Keywords: COPS questionnaire, validation, body dysmorphic disorder

Introduction

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) was first described in 1891 by Italian psychiatrist Enrico Morselli. He introduced the term “dysmorphophobia” which refers to the Greek word “dysmorphia” meaning hideousness [1]. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5), BDD is an excessive concern with perceived appearance defect, associated with meaningful discomfort and deterioration of everyday life functioning [2]. World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases-11 (ICD-11) characterizes BDD as ‘preoccupation with a slight or imagined defect in appearance that causes significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other areas of functioning’ or ‘preoccupations with appearance or self-image causing significant distress or impairment in important areas of functioning [3].

The prevalence of BDD in general population is estimated as 1.9%. It is more common among cosmetic dermatology (9.2%) and cosmetic surgery (13.2%) patients [1, 4]. That is why it is so important to screen subjects before aesthetic procedures for potential symptoms of BDD, as it may be one of the reasons for treatment dissatisfaction and disapproval. There is a limited number of screening instruments for BDD, most commonly the scales proposed by Phillips et al. [5, 6] in mid 1990s. The Cosmetic Procedure Screening Questionnaire (COPS) is an instrument developed by Veale et al. [7] in 2012 to search for BDD symptoms especially in subjects prior to cosmetic procedures.

Aim

As COPS was created in English this study was undertaken to translate and validate its Polish language version. This will enable the use of COPS in clinical practice in subjects speaking Polish.

Material and methods

The Polish language version of the COPS questionnaire was translated and validated according to international standards. The permission to translate the questionnaire was provided by the copyright holders. The COPS questionnaire evaluates the features unattractive for the subjects with regard to diagnostic criteria of BDD. The questionnaire encompasses 9 items which are scored from 0 points (least impaired) to 8 points (most impaired), range 0–72 points. The score is a sum of questions 2 to 10. Items 2, 3 and 5 are reversed. The higher score indicates greater impairment. Individuals who score 40 or more are likely to have a diagnosis of BDD [7, 8].

Translation and validation process

Firstly, the original English version of the COPS questionnaire was translated into Polish by two independent translators. Then the translated versions were compared in terms of inconformity by a third bilingual consultant who is expert in the field and a unified version was created. Subsequently, another independent translator, who was not familiar with the original version of the COPS questionnaire, conducted reverse translation from Polish to English. The reverse translation was sent to the author of the original English version of COPS, who recommended minor changes. The required corrections were implemented accordingly. Finally, the Polish version of the COPS questionnaire was obtained.

After the translation process, the validation was performed. The questionnaire was tested on a group of 33 individuals to assess the level of translation perspicuity, consistency and reproducibility. We recruited a group of subjects who reported to the aesthetic dermatology clinic in order to have an aesthetic procedure in the nearest future (hyaluronic acid fillers and mesotherapy, botulinum toxin, skin resurfacing, vascular laser treatment and rich platelet plasma). The questionnaire was completed by 32 women and 1 man aged 24–50 years (mean age: 35.7 ±7.6 years). In order to determine test-retest reliability the responders were asked to complete the questionnaire twice with a 3–6 days’ interval, which is considered sufficiently long to prevent the individuals from remembering previous answers.

To conduct convergent validity, the subjects were also asked to fill the Polish versions of HADS (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) [9] and BIQLI (Body Image Quality of Life Inventory) [10], the same instruments used for the development of original COPS. HADS consists of two 7-item subscales, one measuring anxiety and another measuring depression, which score separately. Each item is answered on a 4-point (0–3) scale, so the possible scores range from 0 to 21 for each of the two subscales. Using the HADS definitions, the subjects could be grouped as those without symptoms of depression/anxiety (0–10 points) or individuals with symptoms of depression/anxiety (11–21 points). BIQLI uses a 7-point bipolar scale, from highly negative impact to highly positive impact (from –3 to +3). It examines 19 contexts or life domains where body image plays a significant role. The overall body image-related quality of life is calculated as a mean of the 19 life domains of the questionnaire, resulting in a mean BIQLI score. A negative score indicates a negative influence of an individual’s body image on their quality of life, while a positive score may indicate a positive influence.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis of the obtained results was performed with the use of Statistica 13 (Dell, Inc., Tulsa, USA) software. Cronbach α coefficient was used to evaluate the internal consistency of the questionnaire. The Cronbach α coefficient of at least 0.7 indicates for sufficient questionnaire internal consistency, while the value above 0.9 stands for very good internal consistency [11]. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to assess the questionnaire reproducibility (test-retest reliability). Adequate reproducibility of the questionnaire can be acknowledged if ICC is at least 0.7 [12]. The correlation between the answers from a single completion to each question and to the total score was obtained with Spearman correlation test. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to measure the dependences between COPS and other instruments (i.e. HADS and BIQLI) used for convergent validity. Furthermore, responses to each question from the first and the second completion were compared with Wilcoxon test in a search for significant differences, with p-value ≤ 0.05 considered as statistically significant.

Results

The estimation of internal consistency of the Polish language version of COPS demonstrated that the different items of the questionnaire are interrelated. Cronbach α coefficient value for the questionnaire was assessed as 0.76, which indicated good internal consistency for the translated version of the instrument. Highly significant correlations (p < 0.01) were found between the results obtained for each item and the total score of the questionnaire (Table 1). The reproducibility of analysed questionnaire was determined using ICC and assessed as 0.79 for the whole COPS. Moreover, no statistically significant differences were found for each particular question (except for one, i.e. question 2) and COPS total score between the first and second completion (on day 0 and day 3–6) (Table 2). A highly statistically significant, strong positive correlation (r = 0.76, p < 0.0001) was found between the results obtained for total score when filling out the questionnaire twice. Similarly, moderate-to-strong correlations were also found for each particular question (p < 0.01) (detailed data not shown). COPS correlated strongly with BIQLI (r = –0.66, p < 0.01), indicating that higher scores on COPS were associated with lower body image quality of life, as well as with HADS, both depression and anxiety subscales (r = 0.68, p < 0.01 and r = 0.66, p < 0.01, respectively) (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Correlation of each item (Q) score with total score of COPS

| Correlations | N | R Spearman | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q2 and total score | 33 | 0.58 | 0.001 |

| Q3 and total score | 33 | 0.63 | 0.0001 |

| Q4 and total score | 33 | 0.64 | 0.0001 |

| Q5 and total score | 33 | 0.72 | 0.0001 |

| Q6 and total score | 33 | 0.68 | 0.0001 |

| Q7 and total score | 33 | 0.68 | 0.0001 |

| Q8 and total score | 33 | 0.51 | < 0.01 |

| Q9 and total score | 33 | 0.49 | < 0.01 |

| Q10 and total score | 33 | 0.51 | < 0.01 |

Table 2.

Reproducibility of results

| Questions | 1st assessment (points) | 2nd assessment (points) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q2 | 2.85 ±1.89 | 3.21 ±1.95 | 0.02 |

| Q3 | 3.36 ±1.85 | 3.21 ±1.90 | 0.50 |

| Q4 | 3.09±1.74 | 2.94 ±1.87 | 0.66 |

| Q5 | 1.52 ±2.02 | 1.91 ±2.26 | 0.21 |

| Q6 | 2.70 ±1.38 | 2.79 ±1.95 | 0.98 |

| Q7 | 1.21 ±1.90 | 1.39 ±1.94 | 0.27 |

| Q8 | 0.58 ±1.12 | 0.61 ±1.22 | 0.87 |

| Q9 | 0.76 ±1.30 | 0.88 ±1.34 | 0.48 |

| Q10 | 2.79 ±2.12 | 2.58 ±2.05 | 0.14 |

| Total score | 18.85 ±9.11 | 19.51 ±10.16 | 0.68 |

Figure 1.

The correlations between COPS (Cosmetic Procedure Screening Questionnaire) and HADS (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) subscales and BIQLI (Body Image Quality of Life Inventory)

The results presented above proved satisfactory convergent validity, consistency and reproducibility of the translated version of the questionnaire. The individuals reported good intelligibility of the questions and completing of the questionnaire took 3–5 min. The Polish version of COPS is shown in Appendix 1.

Discussion

Body dysmorphic disorder is characterized by preoccupation with thinking and behaviours related to appearance concerns. It is a disabling mental health disorder where a perceived defect in physical outlook impairs everyday life functioning [1, 13–15]. BDD is associated with severe suffering, constant intrusive thoughts, shame, depression, social distancing and poor quality of life [1, 13, 14]. Suicidal ideation and attempts are also more frequent comparing to general population [12]. It should be highlighted that approximately 76% of patients with BDD undergo both cosmetic and surgical treatments in an attempt to ‘fix’ perceived defects in physical outlook [13]. BDD is commonly underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed as physicians are often not confident to diagnose and treat such entity [13]. Moreover, a large proportion of patients with BDD presenting to non-psychiatrist specialists (including aesthetic dermatology professionals) may not identify themselves as suffering from a mental disorder [1]. Many BDD patients seek for dermatological, surgical or cosmetic interventions trying to repair their imagined defect and instead of the psychiatric help that they actually need, they receive treatments, which usually leads to lack of satisfaction with the performed procedure [13]. It is important to improve recognition of BDD which could be achieved by screening subjects before aesthetic treatment. The psychometric assessment could play a significant role in the preliminary selection of aesthetic dermatology patients and choosing the appropriate approach. It is important to implement psychological evaluation in aesthetic medicine clinics as BDD may be not only one of the reasons for treatment dissatisfaction but also increased risk of suffering, depression and suicide [13].

Among the other questionnaires assessing BDD symptoms the COPS questionnaire is the one created for patients undergoing cosmetic procedures [5–7]. This study describes the process of development and validation of the Polish language version of the COPS questionnaire. Comparing to the original version of the COPS questionnaire, the translated Polish language version showed similar, good test-retest reliability (r = 0.87, p < 0.01 vs. r = 0.76, p < 0.0001, respectively) and a lower, however sufficient, value of Cronbach α coefficient (0.91 vs. 0.76, respectively) [7]. Nonetheless, the results of convergent validity revealed very similar results to those obtained in the original paper showing a significant relationship with different standardized measures of body image and psychological distress [7]. Some insignificantly different results of the validation of the Polish language version could be caused by an attempt to keep the very exact meaning of questions from the original questionnaire. It is important to conduct proper validation of every questionnaire used in clinical practice and that is why we attempted to show a detailed and appropriate way of translation and validation of the original questionnaire.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that this version of the instrument may be used for BDD screening in aesthetic dermatology clinics. It could be beneficial in the evaluation of mental health status in cosmetic dermatology subjects and in choosing the proper approach.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Przesiewowy Kwestionariusz Procedur Kosmetycznych (COPS)

Celem tego kwestionariusza jest zrozumienie, co sądzisz o swoim wyglądzie przed zabiegiem kosmetycznym. Wszystkie uzyskane informacje będą ściśle poufne.

Przed udzieleniem odpowiedzi na pytanie numer 1 proszę zapoznać się z przykładem.

Za chwilę poprosimy Cię o opisanie tych cech Twojego wyglądu, których nie lubisz lub które chciałabyś (chciałbyś) poprawić. Jeśli chcesz poprawić więcej niż jedną cechę swojego wyglądu, proszę wymienić je wszystkie w przewidzianym miejscu. Jako pierwszą proszę wpisać tę cechę, która stanowi Twoje największe zmartwienie.

Oto przykład kobiety, której głównym zmartwieniem był jej nos i która w mniejszym stopniu była zaniepokojona swoją skórą i pośladkami.

I. Cechy Twojego wyglądu, które Cię martwią

Proszę opisać te cechy Twojego wyglądu, których nie lubisz lub chciałabyś (chciałabyś) poprawić.

-

Cecha wyglądu

Nos jest zbyt krzywy i garbaty.

-

Cecha wyglądu

Plamy i blizny potrądzikowe na twarzy.

-

Cecha wyglądu

Pośladki są zbyt duże.

Następnie poprosimy Cię o narysowanie wykresu kołowego i oszacowanie, jaki procent Twojego niepokoju przypisany jest dla każdej cechy Twojego wyglądu. Osoba powyżej przedstawiła swój wykres kołowy w ten sposób.

1. Cechy Twojego wyglądu, które Cię martwią

Proszę opisać te cechy Twojego wyglądu, których nie lubisz lub chciałabyś (chciałbyś) poprawić.

A. Cecha wyglądu (cecha wyglądu, która najbardziej Cię martwi)

....................................................................................................................................................................................................................

B. Cecha wyglądu

....................................................................................................................................................................................................................

C. Cecha wyglądu

....................................................................................................................................................................................................................

D. Cecha wyglądu

....................................................................................................................................................................................................................

E. Cecha wyglądu

....................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Teraz proszę narysować wykres kołowy i oszacować, jaki procent Twojego niepokoju przypisany jest dla każdej cechy Twojego wyglądu. Proszę się upewnić, czy suma równa jest 100%!

Proszę uważnie przeczytać poniższy zestaw pytań i zakreślić cyfrę, która najlepiej opisuje sposób, w jaki myślisz o wybranych cechach swojego wyglądu. Przeczytaj uważnie oznaczenia, aby upewnić się, że zakreślasz cyfrę odzwierciedlającą Twoje odczucia, ponieważ niektóre odpowiedzi są napisane w odwrotnej kolejności.

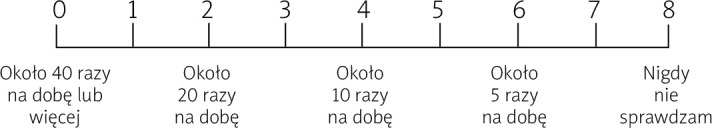

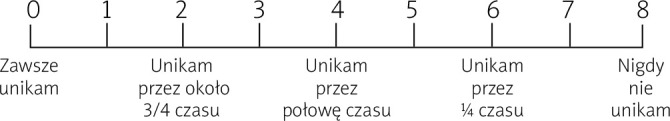

2. Jak często celowo sprawdzasz cechy swojego wyglądu? Nieprzypadkowo zatrzymujesz na nich wzrok. Proszę uwzględnić spoglądanie na ich odbicie w lustrze lub innych powierzchniach, takich jak witryny sklepowe, bezpośrednie patrzenie na nie lub sprawdzanie dotykiem.

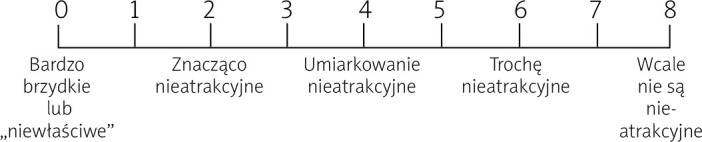

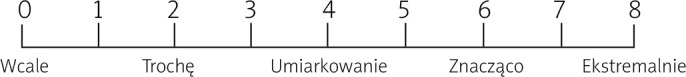

3. Jak bardzo uważasz cechy Twojego wyglądu obecnie za brzydkie, nieatrakcyjne lub „niewłaściwe”?

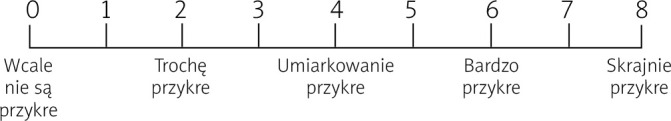

4. Jak bardzo cechy Twojego wyglądu są obecnie dla Ciebie przykre?

5. Jak często cechy Twojego wyglądu prowadzą obecnie do unikania przez Ciebie pewnych sytuacji lub aktywności?

6. Jak bardzo cechy Twojego wyglądu obecnie Cię absorbują? Czy dużo o nich myślisz i ciężko Ci przestać o nich myśleć?

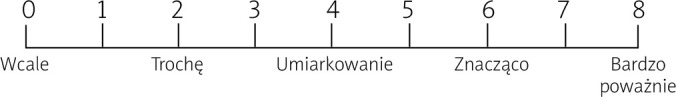

7. Jeśli masz partnera, jak bardzo cechy Twojego wyglądu wpływają obecnie na Wasz związek? Jeśli nie masz partnera, jak bardzo wpływają na randkowanie lub tworzenie związku?

8. Jak bardzo cechy Twojego wyglądu wpływają obecnie na Twoją zdolność do pracy, nauki lub prowadzenia domu? (Proszę odpowiedzieć na pytanie nawet, jeśli nie pracujesz i nie uczysz się, interesuje nas Twoja zdolność do pracy lub nauki.)

9. Jak bardzo cechy Twojego wyglądu wpływają obecnie na Twoje życie towarzyskie?

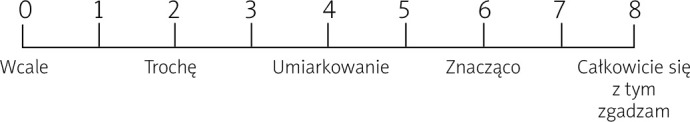

10. Jak bardzo odczuwasz, że Twój wygląd jest najważniejszym aspektem tego kim jesteś?

Copyright D.Veale 2009’.

References

- 1.Singh AR, Veale D. Understanding and treating body dysmorphic disorder. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61(Suppl 1):131–5. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_528_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Text Revision. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organisation . ICD-11 International Classification of Diseases for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. Eleventh Revision. World Health Organisation; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veale D, Gledhill L, Christodolou P, et al. Prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder in different settings. Body Image. 2016;18:168–86. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phillips KA, Atala KD, Pope HG. American Psychiatric Association (Ed.), New research program and abstracts. 148th annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. Miami: American Psychiatric Association; Diagnostic instruments for body dysmorphic disorder. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phillips KA, Hollander E, Rasmussen SA, et al. A severity rating scale for body dysmorphic disorder: development, reliability, and validity of a modified version of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veale D, Ellison N, Werner TG, et al. Development of a Cosmetic Procedure Screening Questionnaire (COPS) for body dysmorphic disorder. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:530–2. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veale D, Eshkevari E, Ellison N, et al. Validation of genital appearance satisfaction scale and the cosmetic procedure screening scale for women seeking labiaplasty. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;34:46–52. doi: 10.3109/0167482X.2012.756865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety And Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cash TF, Fleming EC. The impact of body image experiences: development of the body image quality of life inventory. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;31:455–60. doi: 10.1002/eat.10033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:420–8. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bowyer L, Krebs G, Mataix-Cols D, et al. A critical review of cosmetic treatment outcomes in body dysmorphic disorder. Body Image. 2016;19:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szepietowski JC, Salomon J, Pacan P, et al. Body dysmorphic disorder and dermatologists. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:795–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sjorgen M. The diagnostic work up for body dismorfic disorder. J EC Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;8:72–6. [Google Scholar]