ABSTRACT

Determination of the mechanisms of interspecies transmission is of great significance for the prevention of epidemic diseases caused by emerging coronaviruses (CoVs). Recently, porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) was shown to exhibit broad host cell range mediated by surface expression of aminopeptidase N (APN), and humans have been reported to be at risk of PDCoV infection. In the present study, we first demonstrated overexpression of APN orthologues from various species, including mice and felines, in the APN-deficient swine small intestine epithelial cells permitted PDCoV infection, confirming that APN broadly facilitates PDCoV cellular entry and perhaps subsequent interspecies transmission. PDCoV was able to limitedly infect mice in vivo, distributing mainly in enteric and lymphoid tissues, suggesting that mice may serve as a susceptible reservoir of PDCoV. Furthermore, elements (two glycosylation sites and four aromatic amino acids) on the surface of domain B (S1B) of the PDCoV spike glycoprotein S1 subunit were identified to be critical for cellular surface binding of APN orthologues. However, both domain A (S1A) and domain B (S1B) were able to elicit potent neutralizing antibodies against PDCoV infection. The antibodies against S1A inhibited the hemagglutination activity of PDCoV using erythrocytes from various species, which might account for the neutralizing capacity of S1A antibodies partially through a blockage of sialic acid binding. The study reveals the tremendous potential of PDCoV for interspecies transmission and the role of two major PDCoV S1 domains in receptor binding and neutralization, providing a theoretical basis for development of intervention strategies.

IMPORTANCE Coronaviruses exhibit a tendency for recombination and mutation, which enables them to quickly adapt to various novel hosts. Previously, orthologues of aminopeptidase N (APN) from mammalian and avian species were found to be associated with porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) cellular entry in vitro. Here, we provide in vivo evidence that mice are susceptible to PDCoV limited infection. We also show that two major domains (S1A and S1B) of the PDCoV spike glycoprotein involved in APN receptor binding can elicit neutralizing antibodies, identifying two glycosylation sites and four aromatic amino acids on the surface of the S1B domain critical for APN binding and demonstrating that the neutralization activity of S1A antibodies is partially attributed to blockage of sugar binding activity. Our findings further implicate PDCoV’s great potential for interspecies transmission, and the data of receptor binding and neutralization may provide a basis for development of future intervention strategies.

KEYWORDS: coronavirus, porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV), aminopeptidase N (APN), receptor binding, neutralization, sialic acid

INTRODUCTION

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are single-stranded, positive RNA viruses belonging to the subfamily Orthocoronavirinae of the family Coronaviridae (1). CoV infections can cause mild or lethal respiratory and gastrointestinal diseases in humans and animals, and some CoVs are highly transmissible, exemplified by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic caused by SARS–CoV-2 infection, a member of Betacoronavirus (2, 3). Deltacoronavirus, whose members have been mainly identified in avian species and thus proposed to utilize birds as their original host, is the latest genus to be defined among the four genera of the Orthocoronavirinae (4). Porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) was identified in pigs in many Asian countries and the United States with associated mortality and tremendous economic losses (5–7). PDCoV has an approximately 25.4-kilobase genome that shares the typical gene ordering of CoVs (5′-ORF1a/b; spike [S]; envelope [E]; membrane [M]; NS6; nucleocapsid [N]; NS7-3′) (6–8). In nursing piglets, PDCoV infection causes moderate or severe diarrhea, vomiting, and dehydration, symptoms that are similar to those caused by transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV), porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV), or the newly discovered swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus (SADS-CoV) (7, 9–13).

CoV infection is initiated by binding of the S protein to its receptor on the surface of host cells (14). The CoV S glycoprotein is a class I fusion protein, organized into an N-terminal S1 subunit and a C-terminal S2 subunit (15). Functionally, the S1 subunit contains receptor-binding determinants, whereas the S2 subunit contains membrane anchor and fusion motor domains. Studies on alpha- and betacoronaviruses have shown that both the N- and C-terminal regions of the S1 subunit can function as receptor-binding domains (RBDs) (14, 16). To date, structures of a number of CoV S proteins have been resolved, including that of PDCoV (17–21). The PDCoV S1 subunit is divided into four domains (S1A–D) according to structural analysis (20). S1A (also designated the N-terminal domain [NTD]) has been reported to exhibit sialic acid-binding activity in TGEV (22), bovine coronavirus (BCoV), human HCoV-OC43 (23), and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) (24), contributing to viral entry and host cell tropism. It appears that S1A of most CoVs binds to glycans, with the exception of mouse hepatitis virus (MHV), whose S1A binds to the proteinaceous receptor mCEACAM1a (25, 26). On the other hand, S1B (also designated the C-terminal domain [CTD]) seems to mainly bind to proteinaceous receptors (14). Recently, we and other laboratories have demonstrated that porcine aminopeptidase N (pAPN) and orthologues from avian and various mammalian species play an important role in PDCoV binding and entry into host cells in vitro (27–29). In addition, PDCoV is able to infect calves and chickens in vivo (30, 31), suggesting potential interspecies transmission of PDCoV. Recently, three cases of PDCoV infection in children were reported in Haiti, suggesting that the virus may pose a threat to human health (32).

Interspecies transmission of CoVs poses a significant risk to global public health, exemplified by outbreaks of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in 2002, MERS-CoV in 2012, and SARS–CoV-2 in 2019 (3, 33–35). Since the CoV S1 subunit is a critical target of neutralizing antibodies, it is under heavy evolutionary selective pressure, resulting in a consequence that is more variable than the S2 subunit (14, 36). While receptor binding initiates infection of CoVs, changes within the S1 subunit, particularly within the RBD, are believed to be critical for interspecies transmission (37). A single mutation (K479N) within the S1 protein allowed the cross-species infection of bat SARS-like CoV in human cells, implying that subtle changes in the S protein may lead to significant differences in species specificity (38, 39). Potent neutralizing antibodies are elicited by the RBDs of most CoVs, including TGEV (40), PEDV (41), SARS-CoV (42), and MERS-CoV (43). Therefore, the variety of S1 subunits resulting from the avoidance of neutralization might diversify the ways in which RBDs bind to receptors, promoting the interspecies transmission of CoVs.

In PDCoV, S1B has been shown to interact with domain II of APN, but the role played by S1A in the binding of PDCoV to APN and the mechanism underlying virus neutralization remain unclear. The present study was set up to fill these critical knowledge gaps. We conducted comprehensive PDCoV susceptibility analysis both in vitro (in APN-deficient cultured cells overexpressing APN orthologues) and in vivo (in mice). We also performed functional mutagenesis analysis of the S1A and S1B domains of PDCoV and further investigated whether S1A is able to elicit neutralizing antibodies and the underlying mechanism. The results provide a theoretical basis for the development of intervention strategies against PDCoV infection and interspecies transmission.

RESULTS

APN orthologues from different species mediate PDCoV infection in nonsusceptible cells or porcine small intestine epithelial cells lacking pAPN.

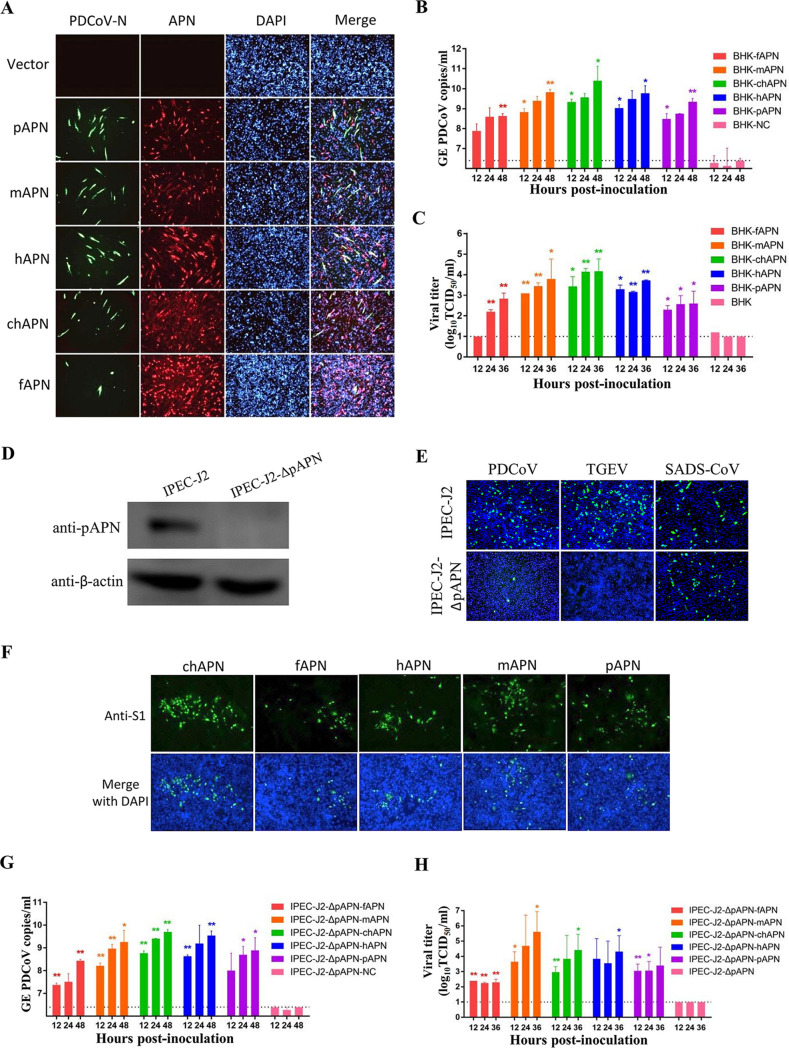

As we have reported previously, expression of pAPN in two nonsusceptible cells allows PDCoV infection (27). We wanted to know whether APN orthologues from other species could also allow PDCoV cell entry. Thus, APNs from humans (hAPN), mice (mAPN), chickens (chAPN), and felines (fAPN) were tested, with pAPN serving as a positive control. Baby hamster kidney (BHK21) cells, which are naturally nonsusceptible to PDCoV likely due to a lack of APN expression (27), were transfected with the different APN orthologues and then inoculated with PDCoV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.5. Infection supernatants were collected for quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis and titer determination at 36 h postinfection (hpi), and the cells were subjected to indirect immunofluorescence assays (IFA) by costaining with a broadly reactive anti-APN antibody (cross-reacted with porcine, murine, or chicken APN) and an anti-PDCoV-N antibody. Expression of APN orthologues made BHK21 capable of supporting productive infection by PDCoV, whereas empty vector did not, demonstrated by IFA (Fig. 1A) and viral genomes and infectious virus in the culture supernatants (Fig. 1B and C).

FIG 1.

Aminopeptidase N (APN) orthologues from different species mediate porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) infection in BHK21 cells and porcine small intestine epithelial cells (IPEC-J2) lacking porcine APN (pAPN). (A) PDCoV infection was detected by immunofluorescence assay (IFA) in BHK-21 cells overexpressing APN orthologues from pigs (pAPN), mice (mAPN), humans (hAPN), chickens (chAPN), and felines (fAPN). After infection with PDCoV (MOI = 0.5), replication of virus or expression of APN orthologues was measured by IFA at 36 hpi using antibodies recognizing the PDCoV nucleocapsid (N) or APN, respectively. Magnification, ×50. (B, C) Genomic RNA copies (B) and infectious viral titers (C) of PDCoV in the supernatant of infected (MOI = 0.5) BHK-21 cells overexpressing APN orthologues. Dashed lines represent the limit of detection (LD) of the qPCR or TCID50. (D) An APN-knockout porcine IPEC-J2 cell line (IPEC-J2-ΔpAPN) was generated and validated to be free of pAPN expression by Western blot using anti-pAPN polyclonal antibodies. As a control, the normal IPEC-J2 cell line is shown expressing the pAPN protein. (E) Effects of pAPN knockout on PDCoV, TGEV, or SADS-CoV infection. PDCoV-N, TGEV-N, or SADS-CoV-N protein expression was detected in PDCoV-, TGEV-, or SADS-CoV-infected cells by IFA at 48 hpi. (F) Susceptibility of IPEC-J2-ΔpAPN cells overexpressing APN orthologues to PDCoV infection was detected by IFA using an anti-PDCoV-S1 antibody at 36 hpi. Magnification, ×50. (G, H) Genomic RNA copies (G) and infectious viral titers (H) of PDCoV in the supernatant of infected IPEC-J2-ΔpAPN cells overexpressing APN orthologues. Dashed lines represent the LD for the qPCR or titration assay. All experiments were performed in duplicate three independent times. The genome RNA copies (B, G) or the viral titers (C, H) from each APN-expressing cell were compared with the control group at the same time point by Student’s t test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Bars indicate standard deviation. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; GE, genome equivalents.

We developed a porcine small intestine epithelial cell line lacking pAPN (IPEC-J2-ΔpAPN) by using CRISPR/Cas9, using Western blot to confirm that pAPN had been knocked out successfully (Fig. 1D). To determine whether IPEC-J2-ΔpAPN cells still supported viral infection, we inoculated them with PDCoV and TGEV. Deletion of pAPN in IPEC-J2 cells almost completely abolished their susceptibility to PDCoV and TGEV (Fig. 1E), finding only a few single immunofluorescent foci representing PDCoV-positive cells. In contrast, pAPN knockout did not affect infection of SADS-CoV (the control) (Fig. 1E), which is known to not utilize APN for cellular entry (44). PDCoV infection of IPEC-J2-ΔpAPN cells was not productive, because no viral RNA or infectious virus was detected (controls) (Fig. 1G and H). Next, we overexpressed the APN orthologues in IPEC-J2-ΔpAPN cells and infected with PDCoV (MOI = 0.5). The APN orthologues enabled PDCoV to infect IPEC-J2-ΔpAPN cells, as evidenced by IFA (Fig. 1F), qPCR (Fig. 1G), and infectious titer (Fig. 1H). These data indicate that PDCoV can utilize multiple APN orthologues from a broad range of species as major entry receptors in vitro. The results are in line with what Li et al. have reported: that APN orthologues of human or chicken can be used by PDCoV for cell entry (28), and the results describe murine APN mediating PDCoV infection in vitro.

Mice are susceptible to PDCoV infection.

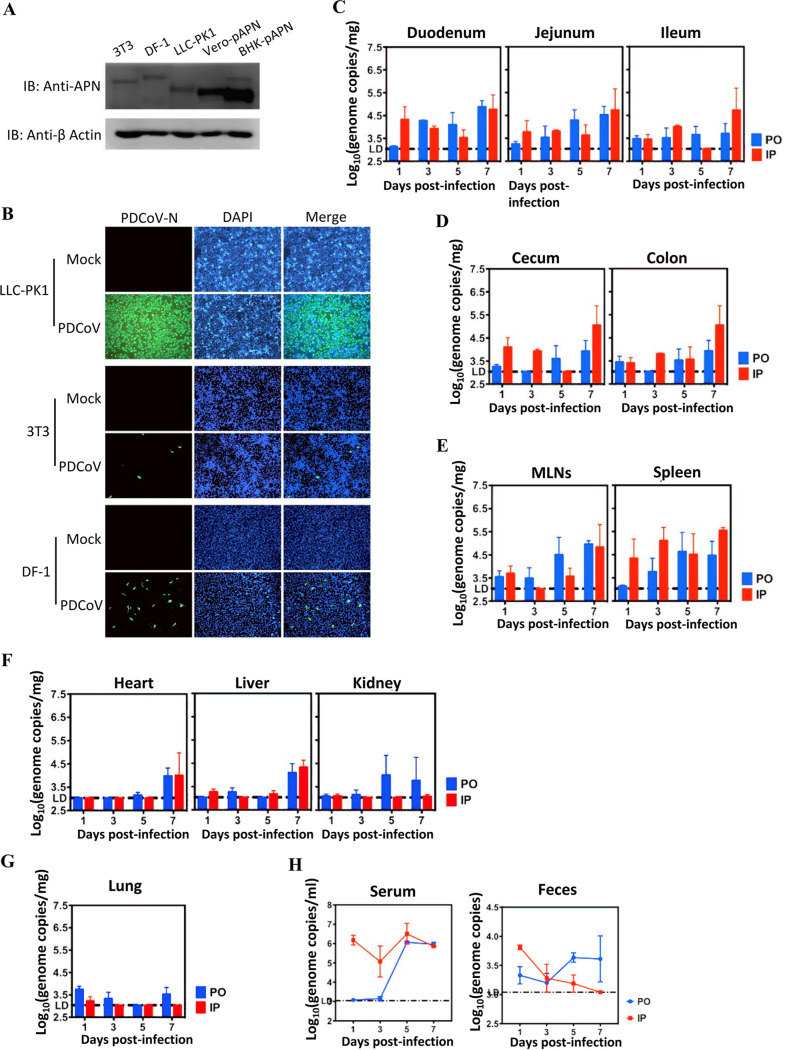

By using a broadly reactive polyclonal antibody against the APN orthologues, we showed that the mouse embryo fibroblast cell line NIH/3T3 or the chicken embryo fibroblast cell line DF-1 endogenously expresses mAPN or chAPN at a detectable level by Western blot analysis, with porcine kidney cells (LLC-PK1), Vero-pAPN, and BHK-pAPN cells (27) serving as positive controls (Fig. 2A). Both NIH/3T3 and DF-1 cells supported PDCoV infection, albeit with lower infection efficiency than LLC-PK1 (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, we tested whether PDCoV could infect mice in vivo. Twenty-four 6-week-old B6 mice were divided into two groups and challenged with 105 PFU PDCoV in 25 μl of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) by the peroral (p.o.) or intraperitoneal (i.p.) route. At 1, 3, 5, and 7 days postinfection (dpi), three mice from each challenge group were euthanized and duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum, colon, mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs), spleen, heart, liver, kidney, lung, blood, and feces were collected. PDCoV RNA was mainly detected in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and lymphoid tissues of mice challenged by either route throughout the experimental period. The viral RNA titer peaked at 7 dpi in the GI tract, lymphoid tissues, and some organs (Fig. 2C through F). In the duodenum, cecum, and spleen, viral RNA titers of i.p.-challenged mice appeared to be slightly higher than in p.o.-challenged mice at early stages of infection (1 and 3 dpi). In contrast, virus RNA was hardly detected in systemic organs until 7 dpi (Fig. 2F), with a very low level in pulmonary tissue (Fig. 2G). With respect to RNAemia, viral RNA load reached a peak at 5 dpi and declined slightly at 7 dpi (Fig. 2H). Similarly, RNAemia of i.p.-challenged mice was significantly higher than in p.o.-challenged mice at 1, 3, and 5 dpi (Fig. 2H). Virus RNA shedding started at 1 dpi, with a gradual reduction and increase over time in the i.p. and p.o. groups, respectively (Fig. 2H). However, inoculation of LLC-PK1 cells with selected PDCoV-positive blood or fecal samples did not recover infectious virus (data not shown). These data demonstrate that mice are susceptible to PDCoV limited infection and that virus RNA shedding may occur upon infection.

FIG 2.

Susceptibility of mice to PDCoV. (A) Endogenous expression of APN orthologues in cell lines derived from mice (NIH/3T3) and chickens (DF-1) by Western blot analysis. Exogenous expressions of Vero-pAPN and BHK-pAPN stable cell lines were used as positive controls. (B) The 3T3, DF-1, and LLC-PK1 cells were infected with PDCoV (MOI = 0.5); infection was measured by IFA at 48 h postinfection using antibodies recognizing the PDCoV-N protein. Magnification, ×50. (C to H) Six-week-old wild-type C57BL/6J mice were inoculated either orally (PO) or intraperitoneally (IP) with 105 PFU of PDCoV per mouse. GI tract tissues (C, D), lymphatic tissues (E), systemic tissues (F), pulmonary tissues (G), serum (H), and feces were collected at 1, 3, 5, and 7 dpi, and PDCoV RNA titers were measured by one-step qRT-PCR targeting the M gene. Three mice for each route of inoculation were euthanized at each time point, and the results are expressed as means ± standard deviation. IB, immunoblot; LD, qPCR limit of detection; MLN, mesenteric lymph node.

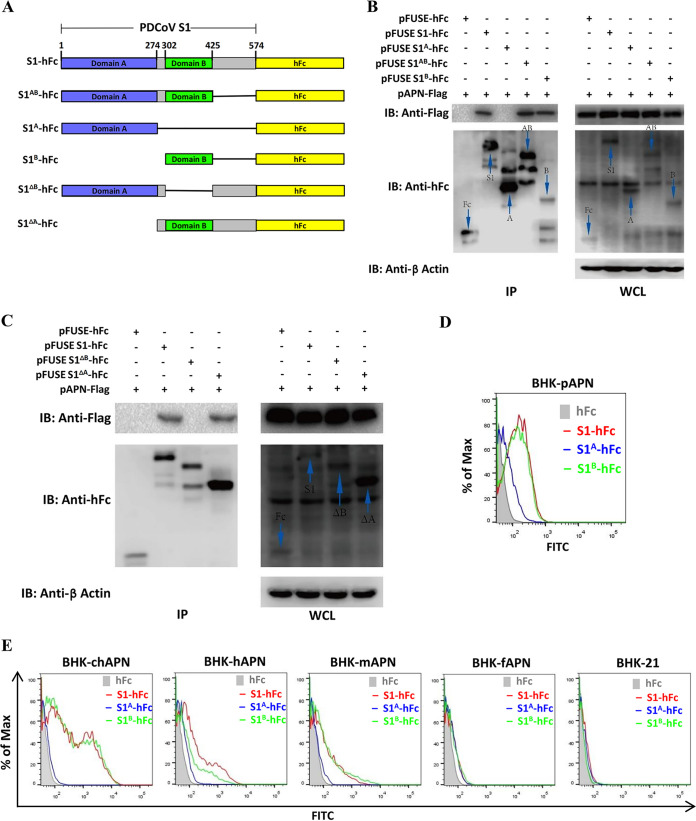

The S1B, not the S1A domain, mainly accounts for the binding of PDCoV to APN orthologues from different species.

The PDCoV S1B domain has been identified as the RBD, with an essential role in PDCoV entry (28). Here, the contribution of PDCoV S1A to pAPN binding was first tested. BHK21 cells were cotransfected with a plasmid encoding pAPN-FLAG along with plasmids encoding different truncated PDCoV S1 peptides of various lengths carrying human Fc (hFc) fusion tags (Fig. 3A), and the cells were subjected to coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) to assess the interactions. All peptides containing the S1B domain (S1-hFc, S1AB-hFc, S1B-hFc, and S1ΔA-hFc) were coprecipitated with pAPN-FLAG (Fig. 3B and C), but not those containing only the S1A domain (S1A-hFc and S1ΔB-hFc). To confirm the interaction between S1B and pAPN, a surface binding assay was performed in BHK-pAPN cells using soluble PDCoV S1-hFc, S1A-hFc, or S1B-hFc chimeric proteins by flow cytometry. The results indicated that S1B mainly accounted for the binding of PDCoV S1 to pAPN, although S1A showed weak binding affinity (Fig. 3D). Next, we examined whether S1A and S1B contributed to the binding to BHK21 cells overexpressing chAPN, hAPN, mAPN, or fAPN. For all tested APN orthologues except for fAPN, soluble S1B mostly accounted for the observed binding (Fig. 3E). Among the tested APN orthologues, chAPN bound S1 and S1B with the strongest affinity, hAPN and mAPN exhibited moderate affinities, and fAPN overexpression hardly conferred susceptibility to PDCoV-S1 and S1B binding (Fig. 3E). S1A did not bind APN in a similar way to S1 and S1B (Fig. 3E) and was detectable only with stably expressed pAPN (Fig. 3D). These data indicate that S1B mainly accounts for the binding of PDCoV S1 to surface-exposed APN orthologues from different species, indicating a crucial role of S1B in PDCoV interspecies transmission.

FIG 3.

The PDCoV S1B domain accounts for the binding of PDCoV S1 to pAPN and its orthologues. (A) Schematic representation of the PDCoV S1 subunit with the two domains (S1A and S1B) indicated, in accordance with the electron cryomicroscopy structure of the PDCoV spike protein (20). (B, C) Coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) analysis of recombinant PDCoV S1 peptides of various lengths binding to pAPN-FLAG. The recombinant PDCoV S1 coding plasmids (2 μg each) were cotransfected with pAPN-FLAG in BHK21 cells in 6-well plates, lysed with MLB lysis buffer, and subjected to co-IP analysis using protein A-conjugated agarose beads at 36 h posttransfection. The protein complex was detected using an HRP-conjugated anti-FLAG Ab and an HRP-conjugated anti-hFc Ab. (D, E) Binding of soluble hFc-tagged PDCoV S1, S1A, S1B, or hFc to BHK-pAPN cells (D) or to BHK21 cells overexpressing chicken (chAPN), human (hAPN), murine (mAPN), or feline (fAPN) APN orthologues (E) was analyzed by flow cytometry. The cells were incubated with hFc-tagged recombinant PDCoV S1, S1A, or S1B peptides, and binding was detected by a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-hFc antibody. WCL, whole-cell lysate.

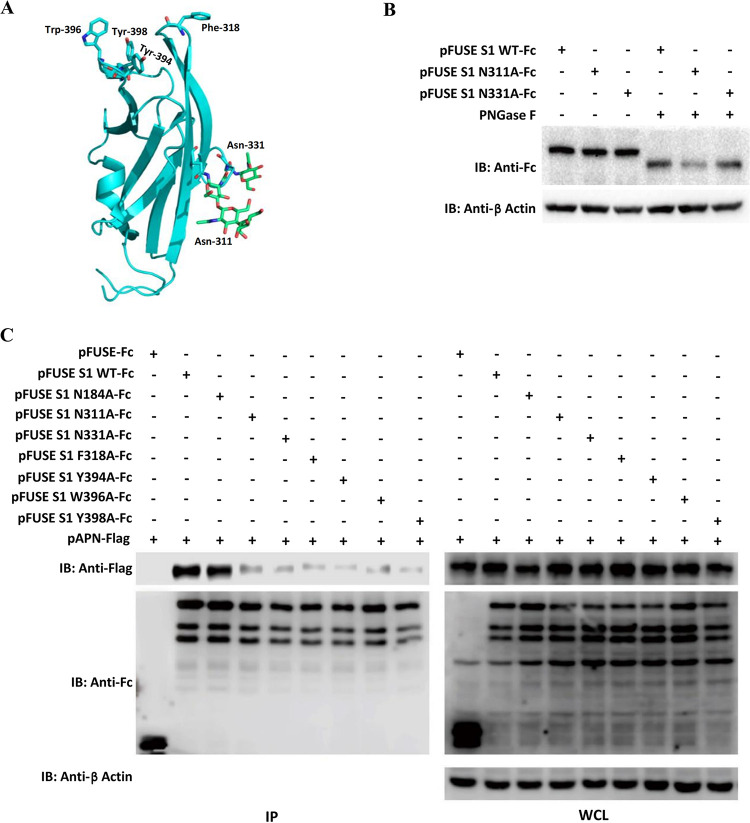

Aromatic amino acids and glycosylation sites within S1B are critical to receptor–RBD interaction.

The PDCoV S1B domain (RBD) has been predicted to display a β-sandwich fold reminiscent of that of alpha-CoVs, harboring topologically similar glycosylation sites (Asn-311 and Asn-331) on the surface revealed by the structural resolution of the PDCoV S glycoprotein (20, 21). Four aromatic residues (Phe-318, Tyr-394, Trp-396, and Tyr-398) at the protruding tips of the β-sandwich fold have also been speculated to mediate a receptor–RBD interaction (Fig. 4A) (20). To determine the role of these amino acids in receptor binding, we constructed seven single substitutions (N184A, N311A, N331A, F318A, Y394A, W396A, and Y398A) in the PDCoV S1, according to the report of Xiong et al. (20). The Asn-311 or Asn-331 S1 mutant protein exhibited the same gel mobility as the wild-type protein, probably due to the limited molecular weight change of a single point mutation in the heavily glycosylated S1. Significant gel mobility shifts were displayed in three proteins by peptide-N-glycosidase F (PNGase F) pretreatment, suggesting removal of total N-linked oligosaccharides (Fig. 4B). Subsequently, co-IP was performed to assess the effects of these mutations on binding affinity to pAPN. The N311A, N331A, F318A, Y394A, W396A, and Y398A mutations within S1B significantly reduced affinity of PDCoV S1 binding to pAPN, whereas N184A (located within S1A), which is reported to have no effect on receptor binding according to the structural analysis (20), had a very small effect, if any (Fig. 4C). All of these data demonstrate that Asn-311, Asn-331, Phe-318, Tyr-394, Trp-396, and Tyr-398 are important for binding of PDCoV S1 to pAPN, implying a significant role of glycosylation and aromatic amino acids of the PDCoV S1B domain in receptor binding.

FIG 4.

Coimmunoprecipitation analysis of PDCoV S1 single amino acid mutants binding to pAPN. (A) Structural feature of the PDCoV S1 domain B (S1B) highlights key aromatic residues likely involved in receptor binding, as well as glycans shown as sticks (Protein Data Bank accession code 6BFU). (B) Wild type and two mutants (N311A and N331A) of hFc-tagged PDCoV S1 constructs were transfected into 293T cells, harvested 36 h posttransfection, and treated with or without PNGase F followed by Western blot analysis using HRP-conjugated anti-hFc Ab. (C) Recombinant hFc-tagged PDCoV S1 mutants containing single amino acid substitutions (N184A, N311A, N331A, F318A, Y394A, W396A, or Y398A) were constructed and cotransfected into 293T cells along with pAPN-FLAG. The cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation with protein A-conjugated agarose beads at 36 h posttransfection, and protein complexes were detected using HRP-conjugated anti-FLAG or anti-hFc antibodies.

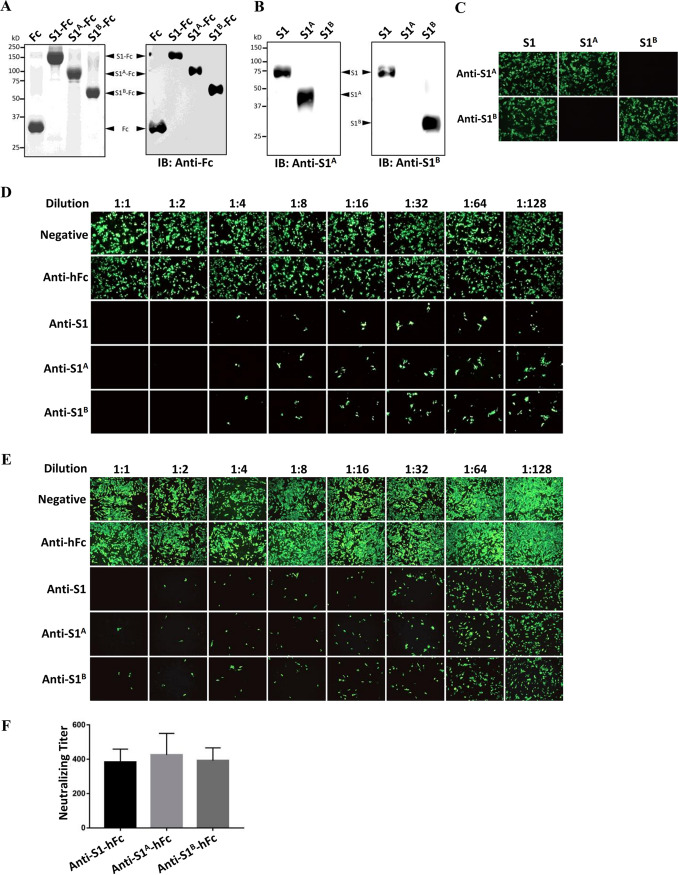

PDCoV S1, S1A, and S1B are able to elicit neutralizing antibodies.

Because the S protein of CoVs is the main determinant of host range, it is also a major target of neutralizing antibodies during infection. The S1 N termini and C termini of several CoVs have been reported to elicit neutralizing antibodies (40, 41). Thus, we next tested whether the full-length PDCoV S1 subunit or its S1A or S1B domain alone could elicit neutralizing antibodies. We immunized BALB/c mice with purified hFc-tagged PDCoV S1, S1A, and S1B peptides expressed in 293T cells (Fig. 5A), and antisera were collected at 3 weeks after the first immunization. Each of the antisera was tested by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and all had titers of more than 1:100,000 (data not shown). By using Western blot or IFA in BHK-21 cells transfected with the recombinant construct expressing S1, S1A, or S1B without the hFc tag, we demonstrated that the generated anti-S1A antisera reacted with the S1 and S1A antigen but not S1B, whereas the anti-S1B antisera recognized the S1 and S1B antigen but not S1A (Fig. 5B and C). The results rule out the possibility of cross-reactivity between S1A and anti-S1B and between S1B and anti-S1A.

FIG 5.

Soluble PDCoV S1, S1A, and S1B peptides can elicit potent neutralizing antibodies. (A) SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of purified hFc-tagged PDCoV S1, S1A, and S1B expressed in the supernatants of 293T cells. These proteins were used as antigens for mouse polyclonal antibody preparation. (B, C) Western blot analysis (B) and IFA (C) in BHK-21 cells transfected with recombinant construct expressing S1, S1A, or S1B without the hFc tag as antigens. Antisera against hFc-tagged S1A or S1B were used for detection at 48 h posttransfection. (D, E) Antisera against hFc-tagged PDCoV S1, S1A, and S1B peptides, but not hFc, blocked infection of PDCoV in BHK-pAPN (D) or LLC-PK1 (E) cells. PDCoV (100 TCID50) was incubated with each antisera for 1.5 h at 37°C prior to infection of BHK-pAPN or LLC-PK1 cells. PDCoV infection was measured by IFA at 36 hpi using an anti-PDCoV-N monoclonal antibiotic (MAb). Magnification, ×50. (F) Virus neutralization titration was performed in LLC-PK1 cells, with titers calculated by the Reed–Muench method.

To determine neutralizing activity, we incubated PDCoV with serially diluted antisera prior to infection of LLC-PK1 and BHK-pAPN cells. All three antisera significantly reduced PDCoV infection in BHK-pAPN and LLC-PK1 cells, whereas anti-hFc as well as negative-control serum did not show any neutralizing effect (Fig. 5D and E). Virus neutralization titration was further performed on LLC-PK1 cells, showing that all three antisera had similar PDCoV-neutralizing titers (∼400) (Fig. 5F). These results indicate that in addition to the PDCoV RBD (S1B), the S1A domain is also highly immunogenic and likely harbors neutralizing epitopes.

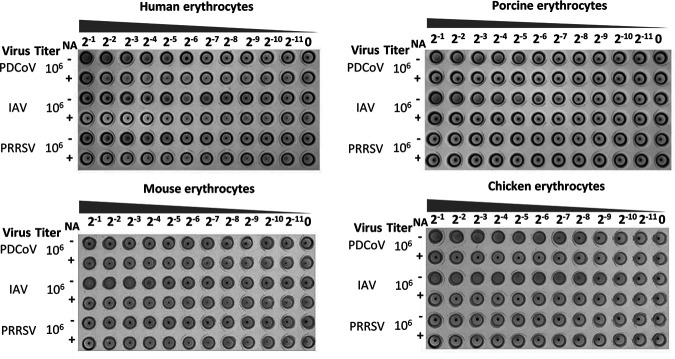

It has been reported that S1A of various CoVs displays a sialic acid-binding activity to promote cell attachment and entry (23, 24, 45, 46). In particular, the PEDV N-terminal domain 0 (S10) serves as the cell attachment domain that is the key target of neutralizing antibodies (41). To determine whether the PDCoV virion is able to bind to sialic acid on the surface of cells from different species, we measured hemagglutination activity of PDCoV using erythrocytes of various species. PDCoV agglutinated human, porcine, and chicken erythrocytes but not mouse erythrocytes, and depletion of cell surface sialic acid by neuraminidase (NA) treatment inhibited the hemagglutination (Fig. 6).

FIG 6.

Hemagglutination assay for PDCoV on erythrocytes from various species. Erythrocytes from humans, pigs, mice, and chickens were pretreated without (−) or with (+) neuraminidase (NA) at room temperature for 2 h before incubation with serial dilutions of PDCoV. Influenza A virus (IAV) and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) served as positive and negative controls, respectively. The undiluted viral titers are shown to the left of each plate.

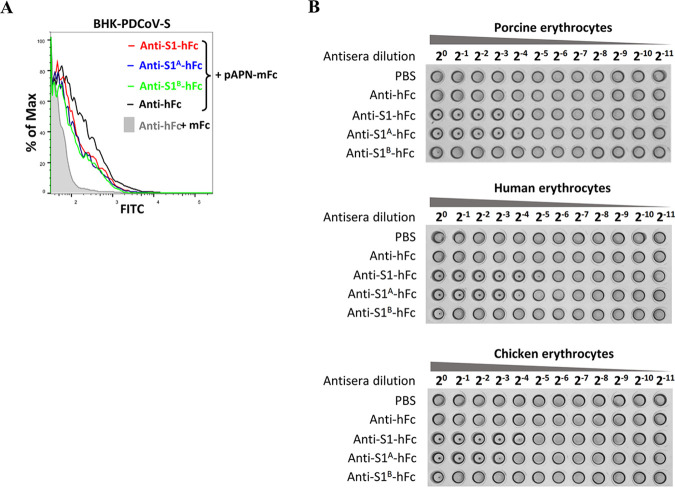

Subsequently, we sought to illustrate the mechanisms underlying the neutralization by antisera. Therefore, we first determined whether the antibodies elicited by S1A or S1B can block the binding of S1 to pAPN. As shown in Fig. 7A, both S1A and S1B antisera blocked the binding of soluble pAPN to BHK cells overexpressing PDCoV-S, with blocking potency comparable to that of S1 antiserum. Next, we tested the effects of antisera on hemagglutination of PDCoV. Antisera against S1 and S1A, but not S1B, exhibited significant inhibitory effect on hemagglutination activity of PDCoV in human, porcine, and chicken erythrocytes (Fig. 7B). These data collectedly demonstrate that the antibodies elicited by the S1A domain neutralize PDCoV infection partially through a blockage of sialic acid binding activity.

FIG 7.

Analysis of the role of neutralizing antibody against PDCoV S1A in the binding of PDCoV spike to sialic acid or receptor. (A) Binding inhibition assays showed that anti-S1, -S1A, and -S1B antibodies inhibited binding of soluble mFc-tagged pAPN to BHK cells expressing PDCoV S protein. BHK cells expressing PDCoV S were incubated with antisera against S1A, S1B, S1, or hFc, followed by incubation with soluble mFc-tagged pAPN. Binding of pAPN was analyzed by flow cytometry using a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-mFc antibody. The mFc peptide was used as a negative control. (B) Hemagglutination inhibition assay showing that anti-S1A but not anti-S1B antibody inhibited hemagglutination activity of PDCoV. PDCoV (106 PFU) was pretreated with serial dilutions of anti-hFc, anti-S1-hFc, anti-S1A-hFc, or anti-S1B-hFc pAb at 37°C for 1 h and subsequently incubated with erythrocytes from pigs, humans, or chickens. PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

DISCUSSION

PDCoV is a newly discovered Deltacoronavirus that has been detected in pig populations in various countries worldwide (7). It may have evolved from an ancestral avian CoV and is most closely related to the CoV HKU17 of sparrows (4). Recently, three cases of PDCoV infection in children reported in Haiti underscore the urgency to study interspecies transmission of this pathogen (32). We previously demonstrated that pAPN is essential for PDCoV infection and proposed that APN orthologues from other mammalian and avian species likely serve as PDCoV receptors (27). While that study was in progress, Li et al. reported that PDCoV can indeed utilize APNs of mammalian and avian species for cell entry by transfection of plasmids encoding hAPN, chAPN, or fAPN in HeLa cells (28). They found that overexpression of these APN orthologues greatly enhanced PDCoV infection in HeLa cells as determined by IFA and counting the percentage of infected cells, although data regarding PDCoV active replication and propagation were not shown (28). The present study also demonstrates that expression of three reported APN orthologues along with mAPN can allow productive PDCoV infection in nonsusceptible BHK21 cells and IPEC-J2-ΔpAPN cells, showing PDCoV antigen expression, viral RNA titers, and progeny virus production (Fig. 1). Among the five APN orthologues, the feline form appeared to have a very low affinity for its S1 ligand, if any (Fig. 3E), and mediated a consequently low susceptibility to PDCoV infection (Fig. 1). We also observed a relatively higher binding to the virus ligand (Fig. 3E) and more efficient replication and production of PDCoV in chAPN-transfected cells than in the other three APN orthologues (Fig. 1). Moreover, chicken DF-1 cells (endogenously expressing chAPN) were susceptible to PDCoV infection (Fig. 2B). These results are also in line with the results of Li et al. (28).

During the evolutionary process, viruses may acquire distinct tissue tropism and pathogenic features in novel hosts through interspecies transmission (35, 47). In the present study, a mouse model was selected for experimental validation of cross-species transmission in vivo. In experimentally infected pigs, PDCoV is mainly distributed in the midjejunum to ileum and, to a lesser extent, in the duodenum, proximal jejunum, and cecum/colon (9, 48–50). Additionally, a small amount of PDCoV antigen is detectable in the intestinal lamina propria, Peyer’s patches, and MLN in infected pigs during the early stage (49, 51). However, PDCoV is not generally detected in other pig organs such as the stomach, lung, heart, tonsil, spleen, liver, and kidney (9, 48). Similar to infection in pigs, PDCoV RNA in mice distributed mainly in the intestinal and lymphoid tissues (Fig. 2). The consistent results show that the tissue tropism of PDCoV may not change markedly when it infects various host species. As PDCoV infection in pigs induces viremia (49), it also induced RNAemia in mice, which is assumed to be the cause of the low level of PDCoV RNA detected in tissues such as the heart, liver, and kidney (7). Notably, viremia may transmit large quantities of virus to the spleen, which is a major peripheral immune organ, accounting for our detection of PDCoV RNA in the spleens of mice. Although PDCoV invades intestinal tissues of pigs and causes diarrhea and vomiting leading to dehydration, no similar symptoms were observed in mice throughout the experimental period. Such asymptomatic infection may support the participation of these species as reservoirs of PDCoV for further interspecies spread.

The ability of the CoV S protein to engage receptors in novel host animals is critical for its interspecies transmission (35). To date, the structures of the S glycoprotein from several CoVs have been resolved, and it is assumed that most CoVs utilize the S1B domain as a proteinaceous RBD that is critical to viral entry and the S1A domain as a sugar binding domain that aids in virus attachment (17, 20, 25, 52–56). Consistently, we found the S1B but not S1A of PDCoV primarily interacted with pAPN (Fig. 3B through D) and bound to APN orthologues (Fig. 3E). It has been suggested that two glycosylation sites on the PDCoV S1B β-sandwich surface and four aromatic amino acids at the protruding tips of the β-sandwich fold play critical roles in receptor binding by analysis of the electron cryomicroscopy structure (20). Our mutagenesis data experimentally confirmed this, suggesting pivotal roles for particular aromatic amino acids and N-linked glycosylation sites in the pAPN binding activity of PDCoV S1B (Fig. 4).

Like S1A of most CoVs, the S1A domain of PDCoV adopts a β-sandwich fold identical to that of human galectins and is able to bind to mucin, suggesting that PDCoV S1A has sugar binding activity (21). Accordingly, PDCoV displayed hemagglutinating activity in porcine, human, and chicken erythrocytes (Fig. 6), suggesting that S1A might aid in PDCoV attachment to multiple species. No hemagglutination was seen for soluble S1A or S1 protein, probably due to a lack of multivalent, high-avidity binding of multiple S proteins that occurs between virus particles and receptors on the surface of erythrocytes (24). In addition, sequence analysis performed by Ye et al. reveals that the PDCoV S1A domain is more prone to mutation, suggesting the contribution of this domain to the adaptation of PDCoV (57).

Neutralizing antibodies are not only a potent means for the host organism to interfere with pathogens but also a stimulus of viral evolution, particularly within selected epitopes. The CoV S1 subunit is the major target of neutralizing antibodies (41, 55, 58, 59). The neutralizing capacity of antibodies elicited by the S1 of Alphacoronavirus and Betacoronavirus has been extensively studied (40, 41, 55, 58, 59). Sequence and structural analysis has revealed that PDCoV S1 is more closely related to that of Alphacoronavirus than to that of Gammacoronavirus (20, 57), which bears multiple epitopes recognized by neutralizing antibodies (40, 41). The neutralizing epitopes of the TGEV S protein distribute not only to the RBD but also to the upstream region of the S1 subunit (40, 55). A recent study on the location of neutralizing epitopes of the PEDV S glycoprotein mapped them to the S10 domain (involved in binding to sialoglycoconjugates) and the S1B domain (41). Like in these porcine alphacoronaviruses, PDCoV S1 was able to elicit potent neutralizing antibodies, specifically the S1A and S1B domains (Fig. 5), consistent with the data of Chen et al. (60). Considering the aforementioned involvement of S1A in cell attachment and S1B in receptor binding (20, 21, 27, 28), antibodies against these domains might neutralize PDCoV by occupying sialic acid-binding sites and/or the proteinaceous receptor-binding sites of the S1 subunit, although other steric factors cannot be excluded. Our data indicate that the neutralization activity of S1A antibodies is attributed, at least partially, to blockage of sugar binding activity (Fig. 7). In notable contrast to most alphacoronaviruses, the S protein of PDCoV lacks an S10 domain that contains potent neutralizing epitopes (20). This omission might decrease the antigenicity of the PDCoV S protein and make it easier for PDCoV to evade the immune system of novel hosts. Moreover, the neutralizing epitopes in S1A and S1B expose these two domains to heavy evolutionary selective pressure, which may increase the probability of mutation and recombination in these domains, further contributing to interspecies transmission.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, viruses, and antibodies.

The PDCoV strain CH/Hunan/2014 was propagated in LLC-PK1 cells (61), whereas the TGEV Purdue strain was produced in ST cells (11). The SADS-CoV (SeACoV) infection in Vero cells has been characterized in our lab previously (62). Infectious virus titers were determined by endpoint dilution, as the 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) in LLC-PK1 cells. HEK-293T, BHK-21, DF-1, NIH/3T3, IPEC-J2, and LLC-PK1 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% or 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. BHK21 cells stably expressing pAPN (BHK-pAPN) were established in our lab as described previously (27). IPEC-J2 cells with selective knockout of pAPN gene (IPEC-J2-ΔpAPN) were constructed using a single-plasmid CRISPR/Cas9 system as described previously (63). Briefly, the knockout strategy was designed by targeting the first pAPN coding DNA sequence (CDS1) with two guide RNAs–Cas9 complexes to delete a 101-bp fragment between nucleotides 100 to 200 downstream of the translation initiation site. Single-cell clones of pAPN knockout lines were obtained by limiting dilution and genotyped by PCR and DNA sequencing; construction details are available upon request. For infection, 5 × 105 or 1 × 106 cells were seeded per well of 12- or 6-well plates, respectively, and then incubated overnight prior to experiments.

An anti-PDCoV-nucleocapsid (N) monoclonal antibody was purchased from Medgene Labs (Brookings, SD, USA), and a broadly reactive polyclonal antibody (pAb) against the APN orthologues was generated in-house. Briefly, the fragment encoding amino acids (aa) 275 to 518 in pAPN with a 6×His tag at the C terminus was expressed in Escherichia coli, purified, and used to immunize two New Zealand White rabbits. Antiserum was harvested and affinity purified at 55 days postimmunization. This antibody cross-reacted to murine or chicken APN endogenously expressed by the mouse embryo fibroblast cell line NIH/3T3 or the chicken embryo fibroblast cell line DF-1 (Fig. 2A).

Plasmid constructs.

The sequence encoding full-length pAPN was amplified from pLV-pAPN as described previously (27) and inserted into a pRK5 vector containing a FLAG tag at its N terminus to construct pAPN-FLAG. The sequences encoding mAPN (GenBank accession no. NM_008486), hAPN (GenBank accession no. NM_001150), chAPN (GenBank accession no. NM_204861), and fAPN (GenBank accession no. U58920.1) were synthesized by Shanghai Generay Biotech Co., Ltd., and inserted into pRK5 vectors with a FLAG tag fused at the N terminus, designated pRK-mAPN, pRK-hAPN, pRK-chAPN, and pRK-fAPN, respectively. The plasmids pFUSE-PDCoV S1-hFc (aa 1 to 574 corresponding to the S protein sequence), pFUSE-PDCoV S1A-hFc (aa 1 to 274), pFUSE-PDCoV S1B-hFc (aa 302 to 425), pFUSE-PDCoV S1AB-hFc (aa 1 to 425), pFUSE-PDCoV S1ΔA-hFc (aa 274 to 574), and pFUSE-PDCoV S1ΔB-hFc (aa 1 to 274 + aa 425 to 574) were constructed by insertion of appropriate clones into the pFUSE-hIgG1-Fc vector (Fig. 3A). Single amino acid substitutions (N184A, N311A, N331A, F318A, Y394A, W396A, and Y398A) were introduced into pFUSE-PDCoV S1-hFc by overlap extension PCR. In addition, three recombinant plasmids harboring S1, S1A, and S1B without the hFc tag were also constructed in the expression vector pRK5, respectively.

Western blot and co-IP.

For co-IP, 1 × 106 transfected cells/well were seeded in a 6-well plate and lysed at 36 h posttransfection by modified lysis buffer (MLB; 25 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1% NP-40, protease cocktail [Biotool]) at 4°C for 15 min. The cell lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 15 min, and the supernatants were incubated for 2 h at 4°C with protein A-conjugated agarose beads in order to precipitate hFc-tagged proteins. After washing with MLB three times, the beads were subjected to Western blot. Briefly, cell lysates or the co-IP products were denatured at 100°C for 5 min, separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Indicated primary antibodies were incubated with the membranes for 3 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C and then horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies were incubated with the membrane for 1 h at room temperature. Images were collected using an ECL imaging system. PNGase F (New England Biolabs, catalogue no. P0704S) was used to deglycosylate PDCoV S1 and mutant S1 proteins as described in the manufacturer’s protocol.

Indirect immunofluorescence assay.

Indirect immunofluorescence assays (IFAs) were performed to detect PDCoV infection in cultured cells. Briefly, PDCoV-infected cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 36 hpi. Then, cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 before incubating with appropriate primary and secondary antibodies and stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Images were collected on a fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems).

Flow cytometry analysis.

Flow cytometry analysis was performed to detect the binding of PDCoV-S1-hFc, PDCoV-S1A-hFc, PDCoV-S1B-hFc, or hFc to APN orthologues. The hFc-tagged proteins were expressed in 293T cells and purified from the supernatant medium using protein A–Sepharose beads (Transbionovo, Beijing, China) as described previously (27). Analysis of sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blot was performed to ensure purity and quality of the recombinant proteins (Fig. 5A and B). For flow cytometry analysis, we followed the protocol described previously (27). Briefly, 10 μg/ml of soluble hFc-tagged S1, S1A, and S1B proteins were incubated with BHK21 cells overexpressing indicated APN orthologues, and binding was detected with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-human IgG Fc antibody (Ab; Thermo Fisher Scientific) by flow cytometry.

Generation of mouse polyclonal antibodies targeting PDCoV-S1, PDCoV-S1A, and PDCoV-S1B.

pAbs against PDCoV-S1, PDCoV-S1A, and PDCoV-S1B were produced in 8-week-old female BALB/c mice after immunization with 10 μg of Fc-tagged PDCoV-S1, PDCoV-S1A, PDCoV-S1B, and hFc mixed with QuickAntibody-Mouse 3W adjuvant (catalogue no. KX0210042; Biodragon), respectively, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each mouse received two subcutaneous injections of Fc-tagged peptides or the Fc peptide alone at 2-week intervals. One week after the second immunization, the mice were sacrificed, and sera were collected, including sera from mock-immunized mice collected as a negative control; serum titers of each mouse were measured by ELISA. Virus neutralization experiments were performed by preincubation of 100 TCID50 PDCoV with serially diluted antisera at 37°C for 1.5 h prior to infection, and the neutralizing titer of each antisera was calculated by the method of Reed–Muench and expressed as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution giving a 50% cytopathic effect.

Animal experiments.

All animal experiments were performed in strict accordance with the guidelines of the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Zhejiang University (approval no. ZJU20170026). Briefly, 6-week-old wild-type C57BL/6J mice (referred to as B6) were purchased from the Model Animal Research Center of Nanjing University (Nanjing, China). All animals were housed in specific-pathogen-free (SPF) isolators under SPF conditions. The mice were inoculated perorally (p.o.) or intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 25 μl containing 105 PFU PDCoV per mouse. For viral load detection in specific tissues, the mice were euthanized at the desired time point, and the tissues were dissected, weighed, and homogenized in medium by beating with 1.0-mm zirconia/silica beads (BioSpec Products, Inc.).

qRT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from tissue homogenates using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). PDCoV RNA load was measured by one-step quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) using the primers 5′-ATCGACCACATGGCTCCAA-3′ and 5′-CAGCTCTTGCCCATGTAGCTT-3′ and the probe FAM-CACACCAGTCGTTAAGCATGGCAAGCT-BHQ (where FAM is 6-carboxyfluorescein, and BHQ is black hole quencher), targeting the membrane (M) gene as described previously (27). Standard curves were established for absolute quantification of PDCoV RNA copy numbers by serial dilution of in vitro-transcribed target RNA. Samples with a cycle threshold value of <35 were considered positive based upon validation data using the RNA standards.

Hemagglutination assay.

Erythrocytes from humans, pigs, mice, and chickens were pretreated or mock pretreated with neuraminidase from Arthrobacter ureafaciens (Roche; diluted to 20 mU/ml in PBS) at room temperature for 2 h followed by washing in PBS three times. Serial 2-fold dilutions of PDCoV, influenza A virus (IAV; H1N1 strain A/PuertoRico/8/34; a gift from Hongjun Chen at Shanghai Veterinary Institute), or porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV; strain VR2385) (64) were incubated with the erythrocytes in V-bottom, 96-well plates for 30 min at 4°C, and then the hemagglutination titer was scored. For hemagglutination inhibition assay with addition of anti-PDCoV antibodies, PDCoV (106 PFU) was pretreated or mock pretreated with serial 2-fold dilutions of anti-hFc, anti-S1-hFc, anti-S1A-hFc, or anti-S1B-hFc pAb at 37°C for 1 h, followed by hemagglutination assay using erythrocytes from pigs, humans, or chickens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Guangdong Major Project of Basic and Applied Basic Research (grant 2020B0301030007), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 32041003 and 31802205), and the Zhaoqing Branch Center of Guangdong Laboratory for Lingnan Modern Agricultural Science and Technology.

Contributor Information

Yao-Wei Huang, Email: yhuang@zju.edu.cn.

Tom Gallagher, Loyola University Chicago.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Groot RJ, Baker SC, Baric R, Enjuanes L, Gorbalenya AE, Holmes KV, Perlman S, Poon L, Rottier PJM, Talbot PJ, Woo PCY, Ziebuhr J. 2011. Coronaviridae, p 806–828. In King AMQ, Adams MJ, Carstens EB, Lefkowitz EJ (ed), Virus taxonomy: ninth report of the international committee on taxonomy of viruses. Elsevier Academic Press, London, England. 10.1016/B978-0-12-384684-6.00068-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, Si HR, Zhu Y, Li B, Huang CL, Chen HD, Chen J, Luo Y, Guo H, Jiang RD, Liu MQ, Chen Y, Shen XR, Wang X, Zheng XS, Zhao K, Chen QJ, Deng F, Liu LL, Yan B, Zhan FX, Wang YY, Xiao GF, Shi ZL. 2020. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 579:270–273. 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Opriessnig T, Huang YW. 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak: could pigs be vectors for human infections? Xenotransplantation 27:e12591. 10.1111/xen.12591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woo PC, Lau SK, Lam CS, Lau CC, Tsang AK, Lau JH, Bai R, Teng JL, Tsang CC, Wang M, Zheng BJ, Chan KH, Yuen KY. 2012. Discovery of seven novel mammalian and avian coronaviruses in the genus Deltacoronavirus supports bat coronaviruses as the gene source of alphacoronavirus and betacoronavirus and avian coronaviruses as the gene source of gammacoronavirus and deltacoronavirus. J Virol 86:3995–4008. 10.1128/JVI.06540-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu H, Jung K, Vlasova AN, Chepngeno J, Lu Z, Wang Q, Saif LJ. 2015. Isolation and characterization of porcine deltacoronavirus from pigs with diarrhea in the United States. J Clin Microbiol 53:1537–1548. 10.1128/JCM.00031-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang YW, Yue H, Fang W, Huang YW. 2015. Complete genome sequence of porcine deltacoronavirus strain CH/Sichuan/S27/2012 from mainland China. Genome Announc 3:e00945-15. 10.1128/genomeA.00945-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung K, Hu H, Saif LJ. 2016. Porcine deltacoronavirus infection: etiology, cell culture for virus isolation and propagation, molecular epidemiology and pathogenesis. Virus Res 226:50–59. 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qin P, Luo WT, Su Q, Zhao P, Zhang Y, Wang B, Yang YL, Huang YW. 2021. The porcine deltacoronavirus accessory protein NS6 is expressed in vivo and incorporated into virions. Virology 556:1–8. 10.1016/j.virol.2021.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma Y, Zhang Y, Liang X, Lou F, Oglesbee M, Krakowka S, Li J. 2015. Origin, evolution, and virulence of porcine deltacoronaviruses in the United States. mBio 6:e00064. 10.1128/mBio.00064-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang YW, Dickerman AW, Pineyro P, Li L, Fang L, Kiehne R, Opriessnig T, Meng XJ. 2013. Origin, evolution, and genotyping of emergent porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strains in the United States. mBio 4:e00737-13. 10.1128/mBio.00737-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan Y, Tian X, Qin P, Wang B, Zhao P, Yang YL, Wang L, Wang D, Song Y, Zhang X, Huang YW. 2017. Discovery of a novel swine enteric alphacoronavirus (SeACoV) in southern China. Vet Microbiol 211:15–21. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang YL, Yu JQ, Huang YW. 2020. Swine enteric alphacoronavirus (swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus): an update three years after its discovery. Virus Res 285:198024. 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y, Liang QZ, Lu W, Yang YL, Chen R, Huang YW, Wang B. 2021. A comparative analysis of coronavirus nucleocapsid (N) proteins reveals the SADS-CoV N protein antagonizes IFN-beta production by inducing ubiquitination of RIG-I. Front Immunol 12:688758. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.688758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hulswit RJG, de Haan CAM, Bosch BJ. 2016. Coronavirus spike protein and tropism changes. Adv Virus Res 96:29–57. 10.1016/bs.aivir.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bosch BJ, van der Zee R, de Haan CA, Rottier PJ. 2003. The coronavirus spike protein is a class I virus fusion protein: structural and functional characterization of the fusion core complex. J Virol 77:8801–8811. 10.1128/jvi.77.16.8801-8811.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li F. 2015. Receptor recognition mechanisms of coronaviruses: a decade of structural studies. J Virol 89:1954–1964. 10.1128/JVI.02615-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walls AC, Tortorici MA, Bosch BJ, Frenz B, Rottier PJM, DiMaio F, Rey FA, Veesler D. 2016. Cryo-electron microscopy structure of a coronavirus spike glycoprotein trimer. Nature 531:114–117. 10.1038/nature16988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuan Y, Cao D, Zhang Y, Ma J, Qi J, Wang Q, Lu G, Wu Y, Yan J, Shi Y, Zhang X, Gao GF. 2017. Cryo-EM structures of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV spike glycoproteins reveal the dynamic receptor binding domains. Nat Commun 8:15092. 10.1038/ncomms15092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ou X, Guan H, Qin B, Mu Z, Wojdyla JA, Wang M, Dominguez SR, Qian Z, Cui S. 2017. Crystal structure of the receptor binding domain of the spike glycoprotein of human betacoronavirus HKU1. Nat Commun 8:15216. 10.1038/ncomms15216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiong X, Tortorici MA, Snijder J, Yoshioka C, Walls AC, Li W, McGuire AT, Rey FA, Bosch BJ, Veesler D. 2017. Glycan shield and fusion activation of a deltacoronavirus spike glycoprotein fine-tuned for enteric infections. J Virol 92:e01628-17. 10.1128/JVI.01628-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shang J, Zheng Y, Yang Y, Liu C, Geng Q, Tai W, Du L, Zhou Y, Zhang W, Li F. 2018. Cryo-electron microscopy structure of porcine deltacoronavirus spike protein in the prefusion state. J Virol 92:e01556-17. 10.1128/JVI.01556-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwegmann-Wessels C, Zimmer G, Schroder B, Breves G, Herrler G. 2003. Binding of transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus to brush border membrane sialoglycoproteins. J Virol 77:11846–11848. 10.1128/jvi.77.21.11846-11848.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwegmann-Wessels C, Herrler G. 2006. Sialic acids as receptor determinants for coronaviruses. Glycoconj J 23:51–58. 10.1007/s10719-006-5437-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li W, Hulswit RJG, Widjaja I, Raj VS, McBride R, Peng W, Widagdo W, Tortorici MA, van Dieren B, Lang Y, van Lent JWM, Paulson JC, de Haan CAM, de Groot RJ, van Kuppeveld FJM, Haagmans BL, Bosch BJ. 2017. Identification of sialic acid-binding function for the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike glycoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114:E8508–E8517. 10.1073/pnas.1712592114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng G, Sun D, Rajashankar KR, Qian Z, Holmes KV, Li F. 2011. Crystal structure of mouse coronavirus receptor-binding domain complexed with its murine receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:10696–10701. 10.1073/pnas.1104306108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams RK, Jiang GS, Holmes KV. 1991. Receptor for mouse hepatitis virus is a member of the carcinoembryonic antigen family of glycoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88:5533–5536. 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang B, Liu Y, Ji CM, Yang YL, Liang QZ, Zhao P, Xu LD, Lei XM, Luo WT, Qin P, Zhou J, Huang YW. 2018. Porcine deltacoronavirus engages the transmissible gastroenteritis virus functional receptor porcine aminopeptidase N for infectious cellular entry. J Virol 92:e00318-18. 10.1128/JVI.00318-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li W, Hulswit RJG, Kenney SP, Widjaja I, Jung K, Alhamo MA, van Dieren B, van Kuppeveld FJM, Saif LJ, Bosch BJ. 2018. Broad receptor engagement of an emerging global coronavirus may potentiate its diverse cross-species transmissibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115:E5135–E5143. 10.1073/pnas.1802879115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu X, Liu S, Wang X, Luo Z, Shi Y, Wang D, Peng G, Chen H, Fang L, Xiao S. 2018. Contribution of porcine aminopeptidase N to porcine deltacoronavirus infection. Emerg Microbes Infect 7:65. 10.1038/s41426-018-0068-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jung K, Hu H, Saif LJ. 2017. Calves are susceptible to infection with the newly emerged porcine deltacoronavirus, but not with the swine enteric alphacoronavirus, porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Arch Virol 162:2357–2362. 10.1007/s00705-017-3351-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boley PA, Alhamo MA, Lossie G, Yadav KK, Vasquez-Lee M, Saif LJ, Kenney SP. 2020. Porcine deltacoronavirus infection and transmission in poultry, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 26:255–265. 10.3201/eid2602.190346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lednicky JA, Tagliamonte MS, White SK, Elbadry MA, Alam MM, Stephenson CJ, Bonny TS, Loeb JC, Telisma T, Chavannes S, Ostrov DA, Mavian C, De Rochars VMB, Salemi M, Morris JG. 2021. Emergence of porcine delta-coronavirus pathogenic infections among children in Haiti through independent zoonoses and convergent evolution. medRxiv 10.1101/2021.03.19.21253391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drosten C, Gunther S, Preiser W, van der Werf S, Brodt HR, Becker S, Rabenau H, Panning M, Kolesnikova L, Fouchier RA, Berger A, Burguiere AM, Cinatl J, Eickmann M, Escriou N, Grywna K, Kramme S, Manuguerra JC, Muller S, Rickerts V, Sturmer M, Vieth S, Klenk HD, Osterhaus AD, Schmitz H, Doerr HW. 2003. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med 348:1967–1976. 10.1056/NEJMoa030747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. 2012. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med 367:1814–1820. 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Graham RL, Baric RS. 2010. Recombination, reservoirs, and the modular spike: mechanisms of coronavirus cross-species transmission. J Virol 84:3134–3146. 10.1128/JVI.01394-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hofmann H, Hattermann K, Marzi A, Gramberg T, Geier M, Krumbiegel M, Kuate S, Uberla K, Niedrig M, Pohlmann S. 2004. S protein of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus mediates entry into hepatoma cell lines and is targeted by neutralizing antibodies in infected patients. J Virol 78:6134–6142. 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6134-6142.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu G, Wang Q, Gao GF. 2015. Bat-to-human: spike features determining “host jump” of coronaviruses SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and beyond. Trends Microbiol 23:468–478. 10.1016/j.tim.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Becker MM, Graham RL, Donaldson EF, Rockx B, Sims AC, Sheahan T, Pickles RJ, Corti D, Johnston RE, Baric RS, Denison MR. 2008. Synthetic recombinant bat SARS-like coronavirus is infectious in cultured cells and in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:19944–19949. 10.1073/pnas.0808116105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sheahan T, Rockx B, Donaldson E, Corti D, Baric R. 2008. Pathways of cross-species transmission of synthetically reconstructed zoonotic severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol 82:8721–8732. 10.1128/JVI.00818-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Godet M, Grosclaude J, Delmas B, Laude H. 1994. Major receptor-binding and neutralization determinants are located within the same domain of the transmissible gastroenteritis virus (coronavirus) spike protein. J Virol 68:8008–8016. 10.1128/JVI.68.12.8008-8016.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li C, Li W, Lucio de Esesarte E, Guo H, van den Elzen P, Aarts E, van den Born E, Rottier PJ, Bosch BJ. 2017. Cell attachment domains of the PEDV spike protein are key targets of neutralizing antibodies. J Virol 91:e00273-17. 10.1128/JVI.00273-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.He Y, Lu H, Siddiqui P, Zhou Y, Jiang S. 2005. Receptor-binding domain of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein contains multiple conformation-dependent epitopes that induce highly potent neutralizing antibodies. J Immunol 174:4908–4915. 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Du L, Zhao G, Yang Y, Qiu H, Wang L, Kou Z, Tao X, Yu H, Sun S, Tseng CT, Jiang S, Li F, Zhou Y. 2014. A conformation-dependent neutralizing monoclonal antibody specifically targeting receptor-binding domain in Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein. J Virol 88:7045–7053. 10.1128/JVI.00433-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang YL, Qin P, Wang B, Liu Y, Xu GH, Peng L, Zhou J, Zhu SJ, Huang YW. 2019. Broad cross-species infection of cultured cells by bat HKU2-related swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus and identification of its replication in murine dendritic cells in vivo highlight its potential for diverse interspecies transmission. J Virol 93:e01448-19. 10.1128/JVI.01448-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krempl C, Ballesteros ML, Zimmer G, Enjuanes L, Klenk HD, Herrler G. 2000. Characterization of the sialic acid binding activity of transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus by analysis of haemagglutination-deficient mutants. J Gen Virol 81:489–496. 10.1099/0022-1317-81-2-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwegmann-Wessels C, Bauer S, Winter C, Enjuanes L, Laude H, Herrler G. 2011. The sialic acid binding activity of the S protein facilitates infection by porcine transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus. Virol J 8:435. 10.1186/1743-422X-8-435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Menachery VD, Graham RL, Baric RS. 2017. Jumping species—a mechanism for coronavirus persistence and survival. Curr Opin Virol 23:1–7. 10.1016/j.coviro.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen Q, Gauger P, Stafne M, Thomas J, Arruda P, Burrough E, Madson D, Brodie J, Magstadt D, Derscheid R, Welch M, Zhang J. 2015. Pathogenicity and pathogenesis of a United States porcine deltacoronavirus cell culture isolate in 5-day-old neonatal piglets. Virology 482:51–59. 10.1016/j.virol.2015.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu H, Jung K, Vlasova AN, Saif LJ. 2016. Experimental infection of gnotobiotic pigs with the cell-culture-adapted porcine deltacoronavirus strain OH-FD22. Arch Virol 161:3421–3434. 10.1007/s00705-016-3056-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jung K, Hu H, Eyerly B, Lu Z, Chepngeno J, Saif LJ. 2015. Pathogenicity of 2 porcine deltacoronavirus strains in gnotobiotic pigs. Emerg Infect Dis 21:650–654. 10.3201/eid2104.141859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jung K, Hu H, Saif LJ. 2016. Porcine deltacoronavirus induces apoptosis in swine testicular and LLC porcine kidney cell lines in vitro but not in infected intestinal enterocytes in vivo. Vet Microbiol 182:57–63. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsai JC, Zelus BD, Holmes KV, Weiss SR. 2003. The N-terminal domain of the murine coronavirus spike glycoprotein determines the CEACAM1 receptor specificity of the virus strain. J Virol 77:841–850. 10.1128/jvi.77.2.841-850.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li F, Li W, Farzan M, Harrison SC. 2005. Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science 309:1864–1868. 10.1126/science.1116480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu K, Li W, Peng G, Li F. 2009. Crystal structure of NL63 respiratory coronavirus receptor-binding domain complexed with its human receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:19970–19974. 10.1073/pnas.0908837106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reguera J, Santiago C, Mudgal G, Ordono D, Enjuanes L, Casasnovas JM. 2012. Structural bases of coronavirus attachment to host aminopeptidase N and its inhibition by neutralizing antibodies. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002859. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen Y, Rajashankar KR, Yang Y, Agnihothram SS, Liu C, Lin YL, Baric RS, Li F. 2013. Crystal structure of the receptor-binding domain from newly emerged Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol 87:10777–10783. 10.1128/JVI.01756-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ye X, Chen Y, Zhu X, Guo J, Da X, Hou Z, Xu S, Zhou J, Fang L, Wang D, Xiao S. 2020. Cross-species transmission of deltacoronavirus and the origin of porcine deltacoronavirus. Evol Appl 13:2246–2253. 10.1111/eva.12997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhou T, Wang H, Luo D, Rowe T, Wang Z, Hogan RJ, Qiu S, Bunzel RJ, Huang G, Mishra V, Voss TG, Kimberly R, Luo M. 2004. An exposed domain in the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein induces neutralizing antibodies. J Virol 78:7217–7226. 10.1128/JVI.78.13.7217-7226.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Du L, Zhao G, Kou Z, Ma C, Sun S, Poon VK, Lu L, Wang L, Debnath AK, Zheng BJ, Zhou Y, Jiang S. 2013. Identification of a receptor-binding domain in the S protein of the novel human coronavirus Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus as an essential target for vaccine development. J Virol 87:9939–9942. 10.1128/JVI.01048-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen R, Fu J, Hu J, Li C, Zhao Y, Qu H, Wen X, Cao S, Wen Y, Wu R, Zhao Q, Yan Q, Huang Y, Ma X, Han X, Huang X. 2020. Identification of the immunodominant neutralizing regions in the spike glycoprotein of porcine deltacoronavirus. Virus Res 276:197834. 10.1016/j.virusres.2019.197834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Qin P, Du EZ, Luo WT, Yang YL, Zhang YQ, Wang B, Huang YW. 2019. Characteristics of the life cycle of porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) in vitro: replication kinetics, cellular ultrastructure and virion morphology, and evidence of inducing autophagy. Viruses 11:455. 10.3390/v11050455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang YL, Liang QZ, Xu SY, Mazing E, Xu GH, Peng L, Qin P, Wang B, Huang YW. 2019. Characterization of a novel bat-HKU2-like swine enteric alphacoronavirus (SeACoV) infection in cultured cells and development of a SeACoV infectious clone. Virology 536:110–118. 10.1016/j.virol.2019.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ji CM, Wang B, Zhou J, Huang YW. 2018. Aminopeptidase-N-independent entry of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus into Vero or porcine small intestine epithelial cells. Virology 517:16–23. 10.1016/j.virol.2018.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huang YW, Dryman BA, Li W, Meng XJ. 2009. Porcine DC-SIGN: molecular cloning, gene structure, tissue distribution and binding characteristics. Dev Comp Immunol 33:464–480. 10.1016/j.dci.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]