Abstract

Background and Objectives

To explore efficacy/safety of natalizumab, a humanized monoclonal anti–α4-integrin antibody, as adjunctive therapy in adults with drug-resistant focal epilepsy.

Methods

Participants with ≥6 seizures during the 6-week baseline period were randomized 1:1 to receive natalizumab 300 mg IV or placebo every 4 weeks for 24 weeks. Primary efficacy outcome was change from baseline in log-transformed seizure frequency, with a predefined threshold for therapeutic success of 31% relative reduction in seizure frequency over the placebo group. Countable seizure types were focal aware with motor signs, focal impaired awareness, and focal to bilateral tonic-clonic. Secondary efficacy endpoints/safety were also assessed.

Results

Of 32 and 34 participants dosed in the natalizumab 300 mg and placebo groups, 30 (94%) and 31 (91%) completed the placebo-controlled treatment period, respectively (one participant was randomized to receive natalizumab but not dosed due to IV complications). Estimated relative change in seizure frequency of natalizumab over placebo was −14.4% (95% confidence interval [CI] –46.1%–36.1%; p = 0.51). The proportion of participants with ≥50% reduction from baseline in seizure frequency was 31.3% for natalizumab and 17.6% for placebo (odds ratio 2.09, 95% CI 0.64–6.85; p = 0.22). Adverse events were reported in 24 (75%) and 22 (65%) participants receiving natalizumab vs placebo.

Discussion

Although the threshold to demonstrate efficacy was not met, there were no unexpected safety findings and further exploration of possible anti-inflammatory therapies for drug-resistant epilepsy is warranted.

Trial Registration Information

The ClinicalTrials.gov registration number is NCT03283371.

Classification of Evidence

This study provides Class I evidence that IV natalizumab every 4 weeks, compared to placebo, did not significantly change seizure frequency in adults with drug-resistant epilepsy. The study lacked the precision to exclude an important effect of natalizumab.

The mainstay therapy for patients with epilepsy is antiseizure drugs (ASDs), which balance neuronal excitation and inhibition.1,2 Approximately 70% of patients achieve seizure control with ASDs.3-5 However, a subset of patients have drug-resistant epilepsy, defined as the failure of adequate trials of 2 tolerated and appropriately chosen and used ASDs to achieve sustained seizure freedom.6 For these patients, surgery, neurostimulation, specialized diets, or other therapies may be employed to control seizures.5

Mechanisms of drug resistance are unclear; however, available ASDs do not target underlying inflammatory processes, which may contribute to drug-resistant epileptic seizures.7,8 Leukocyte trafficking across the blood–brain barrier (BBB), via interaction between α4-integrin and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), may contribute to brain inflammation, BBB leakage, and introduction of plasma constituents to brain parenchyma, ultimately driving seizures.9 This hypothesis was supported in a mouse model of epilepsy where administration of anti–α4-integrin antibodies reduced seizures.10 In humans, elevated brain leukocytes are present in CNS tissue of patients with epilepsy,10,11 and surgical specimens of patients with drug-resistant epilepsy show evidence of increased BBB permeability.11,12

Natalizumab (Tysabri; Biogen) is an anti–α4-integrin monoclonal antibody approved for the treatment of multiple sclerosis.13 We hypothesize that by reducing the BBB dysfunction due to leukocyte–vascular interaction, natalizumab raises the seizure threshold, thereby reducing seizure recurrence. In turn, seizure reduction would decrease neurogenic inflammation caused by seizures themselves, thus breaking the cycle of BBB damage, neuroinflammation, and seizures. Natalizumab reduced epileptic seizures in one patient with Rasmussen encephalitis and another with multiple sclerosis; however, the antiseizure effects may have been associated with “encephalitic-like” etiology.14,15 Therefore, we systematically explored the efficacy and safety of natalizumab as adjunctive therapy in drug-resistant focal epilepsy in the OPUS study.

Methods

Classification of Evidence

The primary research question was as follows: Is adjunctive natalizumab an effective option for treatment of drug-resistant focal epilepsy in adults? This study provides Class I evidence that IV natalizumab every 4 weeks, compared to placebo, did not significantly change seizure frequency in adults with drug-resistant epilepsy. The study lacked the precision to exclude an important effect of natalizumab.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

This study was approved by a regional ethics committee on human experimentation and conducted according to the International Council for Harmonisation and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants (or legal representatives of participants) before screening assessment.

Entry Criteria

Participants aged 18–75 years were eligible for enrollment if they had a clinical diagnosis of focal epilepsy (confirmed by an independent epilepsy review committee) and met the International League Against Epilepsy's 2010 definition of drug resistance.6 In addition, participants must have experienced ≥6 seizures during the baseline period, with no more than 21 consecutive seizure-free days, and been on a stable regimen of 1–5 ASDs during the 4 weeks before the screening visit and throughout the baseline period. Seizure types included focal aware seizures with motor signs, focal impaired awareness seizures, and focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures. Participants who experienced focal aware seizures without motor signs as the only seizure type; had a diagnosis of generalized, combined generalized and focal, or unknown epilepsy; had known progressive structural CNS lesions; had a history of clustered seizures precluding the ability to count individual seizures; and had any clinically significant medical condition that may contraindicate the use of natalizumab were excluded from the study.

Study Design

OPUS was a phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded study conducted at 31 sites across the United States, with baseline and placebo-controlled efficacy periods extending from March 20, 2018, to January 10, 2020. The study consisted of a 6-week prospective baseline period followed by a double-blind, placebo-controlled period lasting 24 weeks, where weeks 0–8 constituted an active run-in period in order for natalizumab to achieve approximately 75% of steady state in participants. Following week 24, participants had the option of continuing in a 24-week open-label period (not reported in this article). A safety phone call occurred 8 weeks after a 12-week posttreatment follow-up. Randomization was performed using interactive response technology and was stratified based on presence or absence of structural etiology for focal epilepsy and seizure frequency (≥24, <24 seizures) during the baseline period. Structural etiology for focal epilepsy is defined as abnormalities visible on structural neuroimaging where the electroclinical assessment together with the imaging findings lead to a reasonable inference that the imaging abnormality is the likely cause of the seizures,16 and this assessment was adjudicated by an independent epilepsy review committee.

Participants received either placebo or natalizumab 300 mg IV in a 1:1 ratio once every 4 weeks for 24 weeks. An electronic seizure diary was used to collect daily records of seizures.17 Participants had the backup option of using paper diaries to enter seizure information, if needed. All participants, their families, and study personnel were blinded to treatment allocation. The end of the placebo-controlled period was defined as after completion of the week 24 assessments, before study treatment administration for the open-label phase.

Predefined Endpoints

The primary efficacy endpoint was change from baseline in log-transformed seizure frequency from weeks 8–24 of the placebo-controlled period, where seizure frequency was defined as the number of seizures per 28 days. Secondary efficacy endpoints included the proportion of participants with ≥50% reduction from baseline in seizure frequency; proportion of participants free from seizures; percentage of seizure-free days gained compared with baseline (number of seizure-free days per 28 days); and the proportion of participants with an inadequate treatment response, defined as modification of ASDs after week 12 of the placebo-controlled period or discontinuation of treatment after the active run-in period due to lack of efficacy. Exploratory endpoints included change from baseline in log-transformed frequencies of focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures and focal (excluding focal to bilateral tonic-clonic) seizures.

Safety assessments included incidence of adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs and clinical laboratory data. Suicidal ideation and behavior evaluation using the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) occurred at the screening visit and all subsequent visits; positivity was defined as a “yes” response on ideation items 4 or 5, or a “yes” response to any behavior item (except nonsuicidal self-injury). Assessment of anti–John Cunningham virus (JCV) antibody status was performed at the screening visit and at week 24.

Serum concentration of natalizumab was recorded at baseline through week 24 for pharmacokinetic evaluation. α4-integrin saturation and soluble VCAM-1 concentration was determined for pharmacodynamic analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Efficacy was analyzed based on the intent-to-treat population, defined as all participants who were randomized and received ≥1 dose of double-blind treatment. Safety results are reported for all participants who were randomized and received any dose of study treatment. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic assessments were made in all participants who received ≥1 dose of study treatment and had ≥1 postbaseline measurement.

The primary endpoint and continuous endpoints were analyzed using a mixed model for repeated measures with treatment, visit, treatment-by-visit interaction, log-transformed baseline seizure frequency (number of seizures per 28 days), and stratification factors as fixed effects. A subgroup analysis of the primary endpoint in participants with an adjudicated presence of structural etiology for focal epilepsy at baseline vs those without structural etiology was conducted using a mixed model for repeated measures with treatment, visit, treatment-by-visit interaction, log-transformed baseline seizure frequency (number of seizures per 28 days), and ≥24 vs <24 seizures at baseline as fixed effects. The discrete endpoints were analyzed using a logistic regression model, with treatment and stratification variables as fixed covariates and log-transformed baseline seizure frequency (number of seizures per 28 days) as a continuous covariate. All efficacy endpoints were measured using data from weeks 8–24 of treatment and were analyzed at the end of the placebo-controlled period. Safety, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic endpoints for the 24-week placebo-controlled period were summarized using standard descriptive statistics or frequency and percentage of participants, where necessary.

To detect a treatment difference of −0.375 between natalizumab and placebo in the primary endpoint with 80% power at a 2-sided significance level of 0.05 and a SD of 0.5, 29 participants per treatment group enrolled in the study were necessary; a discontinuation rate of up to 15% was accounted for during enrollment.

For the proportion of participants with a ≥50% reduction from baseline in seizure frequency, participants who withdrew from treatment and required protocol-specified modifications of ASDs before completion of the placebo-controlled period were considered nonresponders, and for the proportion of participants free from seizures, those with the above 2 circumstances plus those with any missing diary data during weeks 8–24 of treatment were considered not free from seizures.

Data Availability

The study protocol and data are available upon request through biogenclinicaldatarequest.com, the Biogen Data Request Portal. The results of the prespecified primary and secondary endpoints are available on clincialtrials.gov.

Results

Of 32 and 34 participants dosed in the natalizumab 300 mg and placebo groups, 30 (94%) and 31 (91%) completed the placebo-controlled treatment period, respectively. One participant was randomized to receive natalizumab but not dosed due to IV complications (Figure 1). Baseline demographics; disease characteristics, including seizure types; and ASD use are detailed in Table 1. In the natalizumab and placebo groups, participants with a history of epilepsy surgery totaled 10 (31%) and 5 (15%), respectively. Those with a history of neurostimulation totaled 12 (38%; natalizumab) and 16 (47%; placebo) for vagus nerve stimulation and 0 (natalizumab) and 2 (6%; placebo) for responsive neurostimulation. Neurostimulation parameters were kept constant throughout the study, except for one participant who had a dose change by an outside provider between weeks 4 and 8; the participant was allowed to continue in the study because the dose change was not due to an increase in seizure frequency. Magnet swipes were not recorded. Based on review of adjudication committee documentation and observed seizure diary data at the time of analysis, it was noted that classification of some participants by presence or absence of structural etiology for focal epilepsy and seizure frequency (≥24, <24 seizures) during the baseline period differed from what was entered by the study sites into the interactive response technology at the time of randomization. However, a sensitivity analysis was performed in which the randomization stratification factors were replaced by the actual stratification factors in the mixed model for repeated measures for the primary endpoint, and robustness of the study results was demonstrated.

Figure 1. Patient Disposition.

aThe intent-to-treat (ITT) population was defined as all participants who were randomized and received ≥1 dose of double-blind treatment. bThe safety population was defined as all participants who were randomized and received any dose of study treatment.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics, Disease Characteristics, and ASD Use

The least squares mean change (standard error) from baseline in log-transformed seizure frequency from weeks 8–24 was −0.58 (0.165; n = 32) for natalizumab 300 mg and −0.43 (0.162; n = 34) for placebo (Figure 2; primary endpoint), which corresponded to a relative change over placebo of −14.4% (95% confidence interval [CI] –46.1%–36.1%; p = 0.51). The pattern towards a separation in effect between placebo and natalizumab started after the first 4 weeks of treatment, coinciding with when α4-integrin saturation plateaued. Serum concentration of natalizumab (n = 32) peaked at week 20, with a geometric mean (geometric SD) of 27.69 μg/mL (1.842), and then stabilized at week 24 (Figure 3A). Mean (SD) α4-integrin saturation in the natalizumab 300 mg group (n = 30) increased from 21.71% (37.724) at baseline to 76.99% (10.640) at week 24, whereas mean (SD) α4-integrin saturation in the placebo group (n = 33) did not exceed 5.73% (19.256) from baseline to week 24 (Figure 3B). Mean (SD) soluble VCAM-1 decreased from 479.63 ng/mL (145.204) at baseline to 206.06 ng/mL (94.235) at week 24 in the natalizumab 300 mg group (n = 32), and it slightly increased in the placebo group (n = 34) from 485.03 ng/mL (100.287) at baseline to 515.19 ng/mL (112.022) at week 24 (Figure 3C).

Figure 2. Change From Baseline Over Time in Log-Transformed Seizure Frequency.

The overall relative percent change (95% confidence interval) over placebo from weeks 8–24 was −14.38 (−46.13, 36.09). LS = least squares.

Figure 3. Serum Concentration of Natalizumab, Saturation of α4-Integrin, and Soluble Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 (sVCAM-1) Concentration.

(A) Serum concentration of natalizumab 300 mg. (B) Saturation of α4-integrin. (C) sVCAM-1 concentration. GSD = geometric SD.

The proportion of participants with a ≥50% reduction from baseline in seizure frequency during weeks 8–24 was 10/32 (31.3%) for natalizumab 300 mg and 6/34 (17.6%) for placebo (odds ratio 2.09, 95% CI 0.64–6.85; p = 0.22). The relative change over placebo (95% CI) from weeks 8–24 in change from baseline in seizure-free days gained was 46.81% (−9.39%–137.85%; p = 0.12; n = 32 natalizumab, n = 34 placebo). The proportions of participants free from seizures in the natalizumab and placebo groups were 0/32 and 1/34 (2.9%), respectively; 1/32 (3%) in the natalizumab group vs 2/34 (6%) in the placebo group experienced an inadequate treatment response (defined in Methods). Participants who were administered natalizumab showed a decrease of 21.34% (95% CI −44.70% to 11.90%; p = 0.18; n = 32 natalizumab, n = 34 placebo) over placebo in focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizure frequency, whereas focal seizure frequency (excluding focal to bilateral tonic-clonic) increased 6.61% (95% CI −35.49% to 76.17%; p = 0.80; n = 32 natalizumab, n = 34 placebo) over placebo.

There were 32 participants with an adjudicated presence of structural etiology for focal epilepsy at baseline, 20 in the natalizumab group and 12 in the placebo group, and while not reaching statistical significance, there was greater relative reduction in seizure frequency over placebo in this predefined subgroup (−30.29% [95% CI −64.84% to 38.21%]; p = 0.29) compared with the subgroup of participants without structural etiology for focal epilepsy (−5.89% [95% CI −56.32% to 102.73%]; p = 0.87).

AEs were reported in 24 (75%) and 22 (65%) participants receiving natalizumab 300 mg vs placebo (Table 2). One (3%) participant in each treatment group had 1 serious AE (seizure). Two participants had an AE that led to treatment discontinuation: urticaria in the natalizumab group (n = 1 [3%]) and seizure in the placebo group (n = 1 [3%]). AEs of special interest are reported in Table 3; there were no cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). There were no clinically relevant changes in laboratory tests. Within the prior 6 months of the baseline period, during the baseline period, and throughout the placebo-controlled period, there were no per protocol positive suicidal ideation and behavior responses; however, 1 participant in the natalizumab group changed the answer from “no” to “yes” on item 3 of the C-SSRS under suicidal ideation at week 16, and this participant also answered “yes” to self-injurious behavior without suicidal ideation, which was left blank during screening.

Table 2.

Adverse Events

Table 3.

Adverse Events of Special Interest

All results available on clinicaltrials.gov are described here. However, 4 of the exploratory outcomes reported here are not available on clinicaltrials.gov. They are (1) change from baseline in log-transformed frequency of focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures (a priori), (2) change from baseline in log-transformed frequency of focal seizures (a priori), (3) change from baseline in log-transformed frequency in participants with vs without an adjudicated presence of structural etiology for focal epilepsy (post hoc), and (4) change from baseline in log-transformed seizure frequency adjusting for the stratification factors (post hoc).

Discussion

Despite the advancement of ASDs with better tolerability profiles and newly defined mechanisms of action influencing excitation–inhibition balance, the percentage of drug-resistant patients has remained constant over the past few decades.18 Currently available drugs are ineffective for ∼30% of patients with epilepsy, and patients with epilepsy who do not respond to their first 2 ASDs have little chance of achieving seizure freedom with subsequent ASDs.19-21 This emphasizes the need for a novel approach to treat drug-resistant epilepsy.

Evidence for brain inflammation in the pathogenesis of epilepsy has emerged over the past 2 decades.7,8,22 Experiments in animal models of epilepsy have found that injection of inflammation-producing agents lowers seizure thresholds,23 and blockade of inflammatory processes leads to seizure reduction.8,10 In humans, immunotherapy is often effective in decreasing seizures in patients with autoimmune antibodies24; known inflammatory stimulators, such as fevers, may provoke seizures and contribute to epilepsy development25,26; and increased concentrations of inflammatory mediators are found in CNS tissue associated with seizure activity.8,22 Recent imaging studies with PET have shown higher expression of the neuroinflammation marker, translocator protein 18 kDa, in patients with drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy and neocortical seizure foci compared with controls.27,28

OPUS is one of the first placebo-controlled studies of anti-inflammatory drugs in the treatment of epilepsy. The natalizumab-treated group of participants did not achieve a 31% relative reduction in seizure frequency over the placebo group, the study's predefined threshold for therapeutic success. However, the natalizumab-treated group showed a greater reduction in seizure frequency from baseline, a higher proportion of participants achieving a ≥50% reduction in seizure frequency, and a greater number of seizure-free days vs the placebo group, although statistical significance was not attained. The predefined subgroup of participants with an adjudicated presence of structural etiology for focal epilepsy showed a pattern towards greater reduction in seizures over placebo compared with participants without structural etiology for focal epilepsy. The small sample size of the study may have contributed to the limited power to detect statistically significant differences between the natalizumab and placebo groups. In addition, the proportion of participants with focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures observed during the baseline period was higher in the placebo group, potentially downsizing the effect of natalizumab. The increased percent saturation of α4-integrin and decrease in soluble VCAM-1 over time in the natalizumab group vs placebo was consistent with natalizumab's known immunomodulatory mechanism of action. As an anti–α4-integrin antibody, natalizumab binds α4-integrin ligands present on circulating leukocytes and prevents their adhesion to VCAM-1 on the surface of endothelial cells that line BBB vasculature.29 This interaction blocks leukocyte rolling along the internal vessels and subsequent vessel inflammation and leukocyte extravasation to brain parenchyma.29

We found that 84.8% of participants had used ≥5 ASDs or nondrug therapies before this study, and 59.1% were taking ≥3 concomitant ASDs during baseline, including 13.6% taking ≥4 ASDs. The contrasting mechanisms of action of natalizumab vs concomitantly used ASDs in our patient population allowed us to enroll participants with severe drug-resistant epilepsy without exacerbating side effects due to pharmacointeractions. Natalizumab had favorable safety and tolerability over the placebo-controlled period of this study compared with other approved ASDs investigated as adjunctive therapy. There was only 1 incidence (3%; urticaria) of an AE leading to treatment discontinuation in the natalizumab group in OPUS, whereas, in a pooled analysis of 3 phase 3 trials of perampanel, 7.1%–20.8% of treatment-emergent AEs led to treatment discontinuation in the perampanel groups,30 and a phase 3 trial of eslicarbazepine acetate found that 14.0% of treatment-emergent AEs in the eslicarbazepine acetate group led to treatment discontinuation.31

In addition, during this trial there were no incidences of PML, a rare opportunistic infection of the brain caused by the JCV that has been associated with natalizumab use.32 Risk factors for the development of PML include treatment duration, prior immunosuppressant use, and presence of anti-JCV antibodies.33 Although the risk of PML development was extremely low in this study population, given the short treatment duration of natalizumab and minimal prior chronic use of immunosuppressants, it was an important consideration when setting the study's predefined threshold for therapeutic success, because chronic use of natalizumab would likely have been required for treating epilepsy. Participants were monitored for anti-JCV antibody status, although the presence of anti-JCV antibodies did not preclude participation in the study. A PML risk algorithm was provided to the investigators at each study site.13,33

OPUS enrolled a relatively small sample size and was powered to detect a larger effect size than is typical for adjunctive epilepsy trials, considering the potential risk of PML with chronic use of natalizumab as likely required in the treatment of epilepsy. Natalizumab 300 mg did not meet its primary endpoint in a small sample of patients with severely drug-resistant focal epilepsy. Despite not meeting the efficacy threshold, there were no unexpected safety findings, and pharmacodynamic evidence indicating a consistent mechanism of action suggests that there is good reason to continue exploring agents that target inflammatory processes specific to the CNS to manage drug-resistant epilepsy. Future considerations include refining the population of interest to those patients with active neuroinflammation and BBB damage using imaging-associated markers and increasing the number of trial participants.9,27,28

Acknowledgment

Biogen provided funding for medical writing support in the development of this article. Gabrielle Knafler from Envision Pharma Group wrote the first draft of the manuscript based on input from authors and Kristen DeYoung from Envision Pharma Group copyedited and styled the manuscript per journal requirements.

Glossary

- AE

adverse event

- ASD

antiseizure drug

- BBB

blood–brain barrier

- C-SSRS

Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale

- CI

confidence interval

- JCV

John Cunningham virus

- PML

progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

- VCAM-1

vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

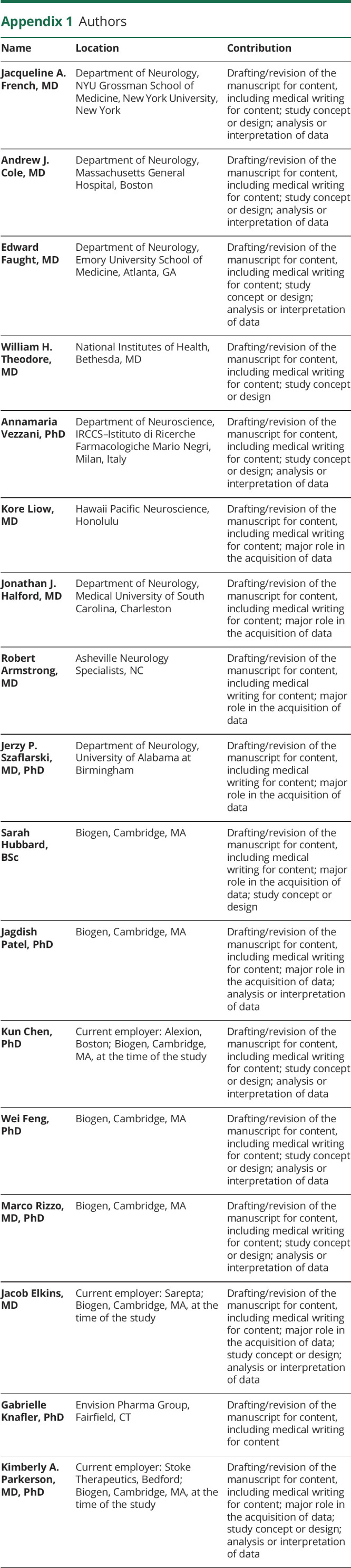

Appendix 1. Authors

Appendix 2. Coinvestigators

Footnotes

Editorial, page 845

Class of Evidence: NPub.org/coe

Study Funding

This study was sponsored by Biogen.

Disclosure

J.A. French receives NYU salary support from the Epilepsy Foundation and for consulting work and/or attending scientific advisory boards on behalf of the Epilepsy Study Consortium from Adamas, Aeonian/Aeovian, Anavex, Arvelle Therapeutics, Inc., Athenen Therapeutics/Carnot Pharma, Axovant, Baergic Bio, Biogen, Biomotiv/Koutif, BioXcel Therapeutics, Blackfynn, Bloom Science, Bridge Valley Ventures, Cavion, Cerebral Therapeutics, Cerevel, Crossject, CuroNZ, Eisai, Eliem Therapeutics, Encoded Therapeutics, Engage Therapeutics, Engrail, Epiminder, Epitel, Fortress Biotech, Greenwich Biosciences, GW Pharma, Idorsia, Ionis, Janssen Pharmaceutica, J&J Pharmaceuticals, Knopp Biosciences, Lundbeck, Marinus, Mend Neuroscience, Merck, NeuCyte, Inc., Neurelis, Neurocrine, Novartis, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development, Ovid Therapeutics Inc., Passage Bio, Pfizer, Praxis, Redpin, Sage, Shire, SK Life Sciences, Sofinnova, Springworks, Stoke, Sunovion, Supernus, Takeda, UCB Inc., West Therapeutic Development, Xenon, Xeris, Zogenix, and Zynerba. J.A. French has also received research grants from Biogen, Cavion, Eisai, Engage, GW Pharma, Lundbeck, Neurelis, Ovid, Pfizer, SK Life Sciences, Sunovion, UCB, Xenon, and Zogenix as well as grants from the Epilepsy Research Foundation, Epilepsy Study Consortium, and NINDS. She is on the editorial board of Lancet Neurology and Neurology Today. She is Chief Medical/Innovation Officer for the Epilepsy Foundation, for which NYU receives salary support. She has received travel reimbursement related to research, advisory meetings, or presentation of results at scientific meetings from the Epilepsy Study Consortium, the Epilepsy Foundation, Adamas, Arvelle Therapeutics, Inc., Axovant, Biogen, Blackfynn, Cerevel, Crossject, CuroNz, Eisai, Engage, Idorsia, Lundbeck, NeuCyte, Inc., Neurelis, Novartis, Otsuka, Ovid, Pfizer, Redpin, Sage, SK Life Science, Sunovion, Takeda, UCB, Xenon, and Zogenix. A.J. Cole is a consultant to Biogen and Sage Therapeutics and serves as data safety monitoring board (DSMB) chair for Medtronic and Ovid. E. Faught is a consultant for Biogen, Neurelis, and Supernus, and serves as DSMB chair for SK Life Science. W.H. Theodore reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. A. Vezzani is an advisory board member for Biogen and CombiGene. K. Liow has received research/grant support from Biogen. J.J. Halford receives research support from Biogen and is a consultant for SK Life Sciences and Takeda. R. Armstrong is on speaker bureaus for Aquestive Therapeutics, Eisai, SK Life Sciences, Sunovion, and UCB. J.P. Szaflarski has received research/grant support from NIH, NSF, Shor Foundation for Epilepsy Research, DoD, UCB Pharma Inc., NeuroPace Inc., Greenwich Biosciences Inc., Biogen Inc., Xenon Pharmaceuticals, Serina Therapeutics Inc., and Eisai, Inc.; reports consulting/advisory board participation for SAGE Therapeutics Inc., Greenwich Biosciences Inc., NeuroPace, Inc., Upsher-Smith Laboratories, Inc., Serina Therapeutics Inc., LivaNova Inc., iFovea, UCB Pharma Inc., Lundbeck, AdCel Biopharma, LLC, and Elite Medical Experts LLC; and is/has been an editorial board member for Epilepsy & Behavior, Journal of Epileptology, Epilepsy & Behavior Reports, Journal of Medical Science, Epilepsy Currents, and Folia Medica Copernicana. S. Hubbard is an employee of Biogen and may own stock in Biogen. J. Patel was an employee of Biogen at the time of the study and may own stock in Biogen. W. Feng is an employee of Biogen and may own stock in Biogen. M. Rizzo is an employee of Biogen and may own stock in Biogen. K. Chen is an employee of Alexion, was an employee of Biogen at the time of the study, and may own stock in Biogen. J. Elkins is an employee of Sarepta, was an employee of Biogen at the time of the study, and holds stock in Biogen and Sarepta. G. Knafler provided writing assistance for manuscript development that was funded by Biogen. K.A. Parkerson is an employee of Stoke Therapeutics, was an employee of Biogen at the time of the study, and holds stock in Biogen. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Macdonald RL, Kelly KM. Antiepileptic drug mechanisms of action. Epilepsia. 1995;36(suppl 2):S2-S12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogawski MA, Löscher W. The neurobiology of antiepileptic drugs. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5(5):553-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Early identification of refractory epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(5):314-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xia L, Ou S, Pan S. Initial response to antiepileptic drugs in patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy as a predictor of long-term outcome. Front Neurol. 2017;8:658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nadkarni S, LaJoie J, Devinsky O. Current treatments of epilepsy. Neurology. 2005;64(12 suppl 3):S2-S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwan P, Arzimanoglou A, Berg AT, et al. Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: consensus proposal by the ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia. 2010;51(6):1069-1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vezzani A, French J, Bartfai T, Baram TZ. The role of inflammation in epilepsy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7(1):31-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vezzani A, Balosso S, Ravizza T. Neuroinflammatory pathways as treatment targets and biomarkers in epilepsy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15:459-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Löscher W, Friedman A. Structural, molecular, and functional alterations of the blood-brain barrier during epileptogenesis and epilepsy: a cause, consequence, or both? Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(2):591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fabene PF, Navarro Mora G, Martinello M, et al. A role for leukocyte-endothelial adhesion mechanisms in epilepsy. Nat Med. 2008;14:1377-1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ravizza T, Gagliardi B, Noé F, Boer K, Aronica E, Vezzani A. Innate and adaptive immunity during epileptogenesis and spontaneous seizures: evidence from experimental models and human temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;29(1):142-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Vliet EA, da Costa Araújo S, Redeker S, van Schaik R, Aronica E, Gorter JA. Blood–brain barrier leakage may lead to progression of temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain. 2007;130(pt 2):521-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tysabri [package Insert]. Biogen Inc.; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bittner S, Simon OJ, Göbel K, Bien CG, Meuth SG, Wiendl H. Rasmussen encephalitis treated with natalizumab. Neurology. 2013;81(4):395-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sotgiu S, Murrighile MR, Constantin G. Treatment of refractory epilepsy with natalizumab in a patient with multiple sclerosis: case report. BMC Neurol. 2010;10:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scheffer IE, Berkovic S, Capovilla G, et al. ILAE classification of the epilepsies: position paper of the ILAE commission for classification and terminology. Epilepsia. 2017;58(4):512-521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel J, Feng W, Chen K, et al. Use of an electronic seizure diary in a randomized, controlled trial of natalizumab in adult participants with drug-resistant focal epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2021;118:107925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engel J Jr. What can we do for people with drug-resistant epilepsy? The 2016 Wartenberg Lecture. Neurology. 2016;87(23):2483-2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nair DR. Management of drug-resistant epilepsy. Continuum. 2016;22(1 Epilepsy):157-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brodie MJ. Outcomes in newly diagnosed epilepsy in adolescents and adults: insights across a generation in Scotland. Seizure. 2017;44:206-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xue-Ping W, Hai-Jiao W, Li-Na Z, Xu D, Ling L. Risk factors for drug-resistant epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(30):e16402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vezzani A, Granata T. Brain inflammation in epilepsy: experimental and clinical evidence. Epilepsia. 2005;46(11):1724-1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sayyah M, Javad-Pour M, Ghazi-Khansari M. The bacterial endotoxin lipopolysaccharide enhances seizure susceptibility in mice: involvement of proinflammatory factors: nitric oxide and prostaglandins. Neuroscience. 2003;122(4):1073-1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vincent A, Irani SR, Lang B. The growing recognition of immunotherapy-responsive seizure disorders with autoantibodies to specific neuronal proteins. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23(2):144-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dubé CM, Brewster AL, Richichi C, Zha Q, Baram TZ. Fever, febrile seizures and epilepsy. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:490-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Baalen A, Vezzani A, Häusler M, Kluger G. Febrile infection–related epilepsy syndrome: clinical review and hypotheses of epileptogenesis. Neuropediatrics. 2017;48(1):5-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dickstein LP, Liow J-S, Austermuehle A, et al. Neuroinflammation in neocortical epilepsy measured by PET imaging of translocator protein. Epilepsia. 2019;60(6):1248-1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gershen LD, Zanotti-Fregonara P, Dustin IH, et al. Neuroinflammation in temporal lobe epilepsy measured using positron emission tomographic imaging of translocator protein. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(8):882-888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCormack PL. Natalizumab: a review of its use in the management of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Drugs. 2013;73(13):1463-1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwan P, Brodie MJ, Laurenza A, FitzGibbon H, Gidal BE. Analysis of pooled phase III trials of adjunctive perampanel for epilepsy: impact of mechanism of action and pharmacokinetics on clinical outcomes. Epilepsy Res. 2015;117:117-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trinka E, Ben-Menachem E, Kowacs PA, et al. Efficacy and safety of eslicarbazepine acetate versus controlled-release carbamazepine monotherapy in newly diagnosed epilepsy: a phase III double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, multicenter study. Epilepsia. 2018;59(2):479-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pardo G, Jones DE. The sequence of disease-modifying therapies in relapsing multiple sclerosis: safety and immunologic considerations. J Neurol. 2017;264(12):2351-2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bloomgren G, Richman S, Hotermans C, et al. Risk of natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(20):1870-1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The study protocol and data are available upon request through biogenclinicaldatarequest.com, the Biogen Data Request Portal. The results of the prespecified primary and secondary endpoints are available on clincialtrials.gov.