Abstract

BACKGROUND

Brunner’s gland hyperplasia (BGH) is a rare benign lesion of the duodenum. Lipomatous pseudohypertrophy (LiPH) of the pancreas is an extremely rare disease. Because each condition is rare, the probability of purely coincidental coexistence of both conditions is extremely low.

CASE SUMMARY

We report a 26-year-old man presenting to our hospital with symptoms of recurrent upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed a huge pedunculated polypoid lesion in the duodenum with bleeding at the base of the lesion. Histopathological examination of the duodenal biopsy specimens showed BGH. Besides, abdominal computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging revealed marked fat replacement over the entire pancreas, confirmed by histopathological evaluation on percutaneous pancreatic biopsies. Based on the radiological and histological findings, LiPH of the pancreas and BGH were diagnosed. The patient refused any surgical intervention. Therefore, he was managed with supportive treatment. The patient’s symptoms improved and there was no further bleeding.

CONCLUSION

This is the first well-documented case showing the coexistence of LiPH of the pancreas and BGH.

Keywords: Lipomatous pseudohypertrophy, Pancreas, Gastrointestinal bleeding, Brunner’s gland, Case report

Core Tip: Brunner’s gland hyperplasia (BGH) and lipomatous pseudohypertrophy (LiPH) of the pancreas are rare diseases. We present a case with coexisting LiPH of the pancreas and a huge pedunculated BGH of the duodenum that presented with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed a large submucosal mass along the duodenum with central ulceration, and radiological examination showed marked thickening of the duodenal walls and fatty replacement over the entire pancreatic parenchyma. Diagnoses of BGH and LiPH were confirmed by histological evaluations. Although rare, BGH can cause gastrointestinal bleeding. Furthermore, this case highlights the usefulness of combined esophagogastroduodenoscopy and radiological examinations in patients with melena.

INTRODUCTION

Brunner’s gland hyperplasia (BGH) is a rare, benign proliferative lesion of exocrine glands mainly located in the submucosal layer of the duodenum[1]. Most BGHs are asymptomatic[2,3], but some present with abdominal pain, upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and may be associated with obstruction[4-9]. Lipomatous pseudohypertrophy (LiPH) of the pancreas is an extremely rare disease, characterized by the replacement of exocrine pancreatic parenchyma with mature fatty tissue[10,11]. We report a patient who presented with symptoms of GI bleeding from a huge pedunculated BGH of the duodenum with concurrent LiPH of the pancreas. This report can be useful for both education and clinical practice purposes.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 26-year-old male patient was admitted with symptoms of fatigue, tiredness, generally being unwell, melena and anemia.

History of present illness

His illness had begun 2 wk before with intermittent dark stools. Three days to presentation, he had a fever of 39C and right quadrant pain. He experienced an unexplained weight loss of 13 kg within 2 wk. He denied current or prior alcohol consumption, smoking, or drug use.

History of past illness

The patient had a medical history of surgery for intestinal obstruction due to adhesion 2 mo before the current admission, which was associated with a previous operation for intussusception at the age of 13 years. Two years ago, he also had melena managed with blood transfusion and proton pump inhibitors.

Personal and family history

No significant family history or risk factors for GI pathologies were found.

Physical examination

Physical examination showed clinical signs of anemia, otherwise within normal limits. No sign of jaundice was observed. His abdomen was flat and soft without tenderness or palpable mass. His height was 162 cm and his weight was 49 kg (body mass index 18.7 kg/m2).

Laboratory examinations

Hematological investigations showed iron deficiency anemia with 72 g/L hemoglobin (normal range, 135–175 g/L). Other laboratory data revealed an elevated serum total bilirubin of 35 mol/L (normal range ≤ 17 mol/L), alkaline phosphatase of 380 U/L (normal range 40–129 U/L) and increased serum C-reactive protein of 30 mg/dL (normal range ≤ 0.05 mg/dL) and procalcitonin of 17.6 ng/mL (normal range ≤ 0.05 ng/mL) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Laboratory data on admission

|

|

Value

|

Reference range

|

|

| Peripheral blood | |||

| White blood cells | 11.8 | 4× 109–10 × 109/L | |

| Red blood cells | 2.77 | 4.5 × 1012–5.9 × 1012/L | |

| Hemoglobin | 72 | 135–175 g/L | |

| Platelets | 307 | 150 × 109–400 × 109/L | |

| Serum | |||

| Glucose | 5.6 | 4.6–6 mmol/L | |

| Creatinine | 63 | 72–127 µmol/L | |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 1.5 | 3.2–7.4 mmol/L | |

| Total Protein | 68 | 66–87 g/L | |

| Albumin | 34 | 35–52 g/L | |

| Total Bilirubin | 35 | ≤ 17 mol/L | |

| AST | 22 | ≤ 37 U/L | |

| ALT | 25 | ≤ 41 U/L | |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 380 | 40-129 U/L | |

| Amylase | 69 | 13–53 U/L | |

| Lipase | 116 | 13–60 U/L | |

| Procalcitonin | 17.6 | < 0.05 ng/mL | |

| CRP | 30 | < 0.05 mg/dL | |

| Ferritin | 61 | 30–400 ng/mL | |

| Iron | 2.1 | 8.1–28.6 µm/L | |

| IgG4 | 237.5 | 39.2–864 mg/L | |

| Anti–ANA | Negative | ||

| Anti – dsDNA | Negative | ||

| HBsAg | Negative | ||

| Anti-HCV | Negative | ||

| Fasciola hepatica antibody test | Negative | ||

AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine transaminases; CRP: C-reactive protein; ANA: antinuclear antibody; dsDNA: double stranded DNA; HbsAg: hepatitis B surface antigen; HCV: hepatitis C virus.

Imaging examinations

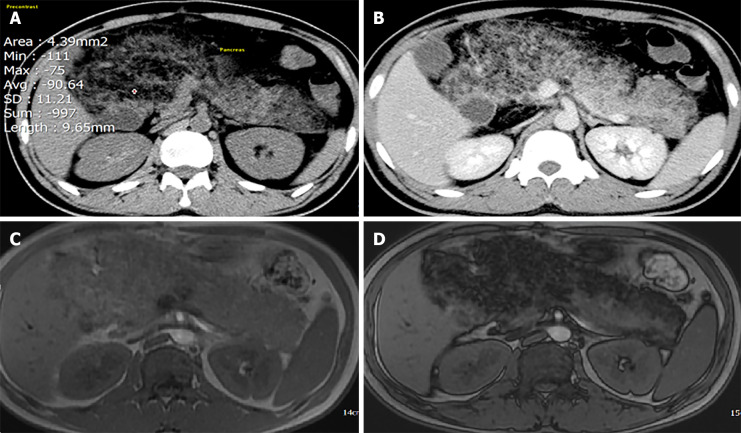

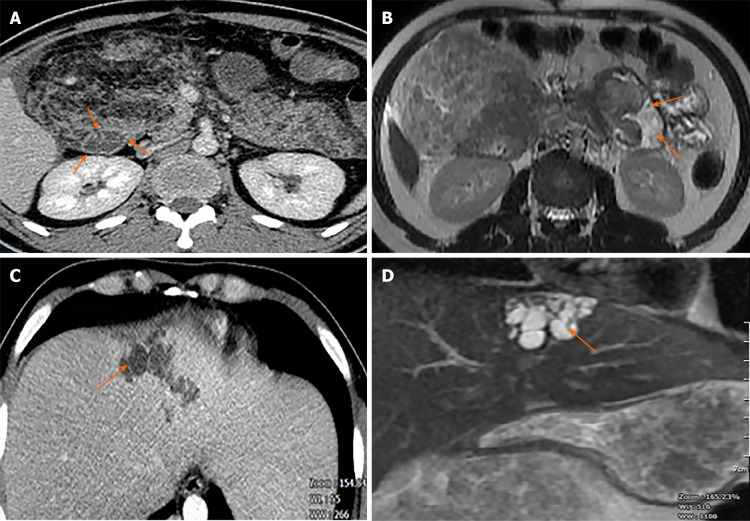

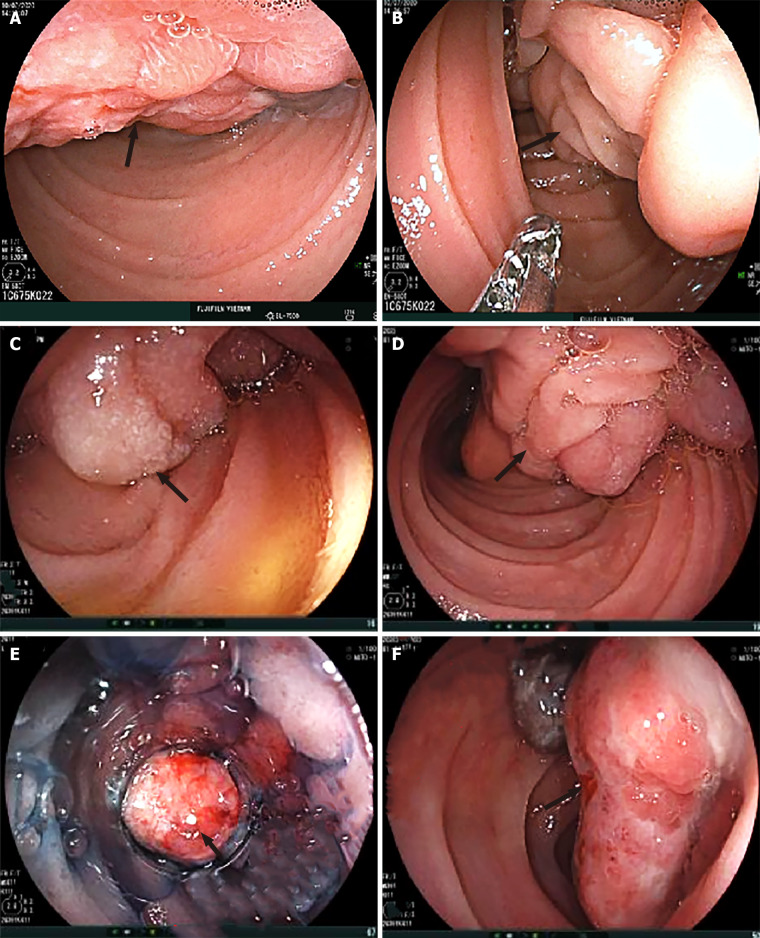

Dynamic abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed marked thickening of the duodenal walls and fatty replacement over the entire pancreatic parenchyma with no delineation between the pancreas and duodenum. The main pancreatic duct was not narrowed or dilated, and no tumor was detected (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with T1-weighted, T2-weighted, and fat-suppression images showed a large mass-like lesion containing adipose tissue from the pancreatic head to tail (Figure 1). Fatty tissue infiltrated not only the pancreatic parenchyma but also the duodenal wall (Figure 2A, B). Both CT and MRI findings suggested the diagnosis of LiPH. Furthermore, focal cystic dilatations of intrahepatic bile ducts in the left hepatic lobe (localized biliary ectasia) were also detected on CT and MRI (Figure 2C, D). Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed a large submucosal mass along the C-shaped loop of the duodenum, the size of the tumor was about 100 mm in the longest diameter with central ulceration, which was considered the origin of bleeding (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A: Plain CT: density of the pancreatic parenchyma was uniformly decreased to the same level as that of the surrounding fatty tissue (attenuation value = 90.64 HU); B: Contrast-enhanced CT: Pancreatic parenchyma was absent, completely replaced by fat; C and D: MRI of the pancreas. In- and out-phase MRI respectively show a typical global (C) hyperintensity; and (D) fat suppression.

Figure 2.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A: CECT showing fatty tissue infiltration into duodenal wall (orange arrows); B: MRI also showed fatty tissue infiltration into duodenal wall (orange arrows); C: CECT scan showed hypoechoic saccular dilatations in segment IV of the liver; D: T2-weighted MRI showed segmental biliary ectasia (arrow).

Figure 3.

Endoscopic appearance of the submucosal tumor arising from the duodenum (arrows). A: Irregular surface with shallow ulcers; B–D: A thick stalk below the head portion of the tumor; E and F: Surface ulcers with bleeding.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

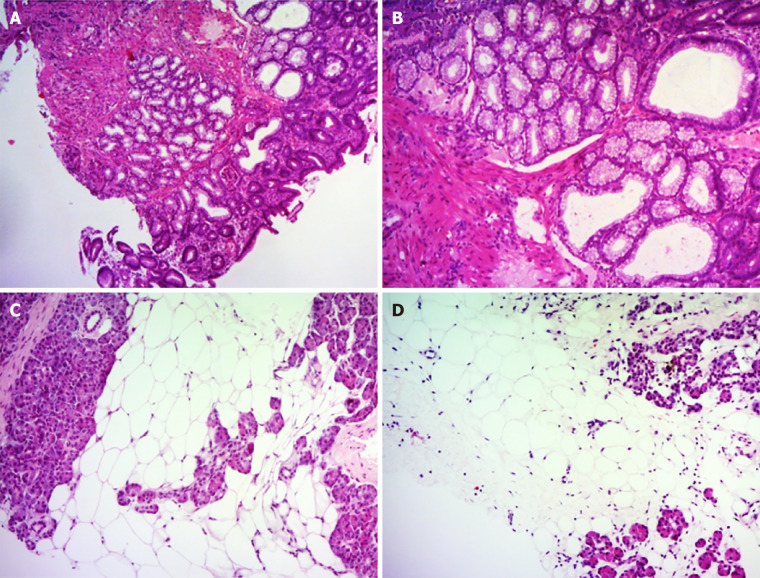

Multiple biopsies were taken from the duodenal mass. Histological examination confirmed the diagnosis of BGH (Figure 4). Ultrasound-guided percutaneous pancreatic biopsy was also performed. Histological features of the biopsy specimens revealed the pancreatic parenchyma was diffusely replaced with adipose tissue, but some retained pancreatic acini, pancreatic ducts, and islets of Langerhans were identified with a scattered distribution (Figure 4), confirming a diagnosis of LiPH of the pancreas.

Figure 4.

Histological findings of duodenal and pancreatic biopsy specimens. A and B: The duodenal biopsy showed lobulated proliferation of submucosal Brunner’ glands comprising benign-looking acini lined by mucous cells with basal nuclei without atypia, which was consistent with Brunner’s gland hyperplasia. C and D: Percutaneous pancreatic biopsies revealed adipose tissue replacing the pancreatic parenchyma. Some pancreatic acini were identified with a scattered distribution. Hematoxylin and eosin stain (A–D). Original magnification: (A, C, D) × 40, (B) × 100.

TREATMENT

Since the patient showed acute upper GI bleeding and anemia, blood transfusion was conducted. Because of the risk of recurrent bleeding and the difficulty in endoscopic resection of BGH due to its huge size, poor endoscopic visibility and maneuverability, surgery was recommended. However, the patient refused any surgical intervention. Therefore, he was managed with supportive treatment including proton pump inhibitors.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient’s symptoms improved, and he has been followed up for 6 mo regularly with no further bleeding as an outpatient. He gained weight up to 62 kg.

DISCUSSION

This is a case report of the coexistence of two rare conditions, LiPH of the pancreas and a huge pedunculated BGH of the duodenum, in which the patient presented with upper GI bleeding secondary to ulceration of BGH.

Brunner’s glands are tubuloalveolar exocrine glands predominantly located in the submucosa of the proximal duodenum. Their main function is to secrete mucin glycoproteins, and bicarbonate, forming a mucus layer that protects underlying duodenal mucosa from gastric acid, pancreatic enzymes, and other surface-active agents[12]. BGH of the duodenum belongs to the spectrum of benign Brunner’s gland proliferations, which are variously termed as BGH, Brunner’s gland adenoma, and Brunner’s gland hamartoma. However, the distinction between these diagnoses is obscure and the terms are used interchangeably in the literature[2,13,14]. Histologically, several authors have classified benign Brunner’s gland proliferations based on their tissue components. BGH is characterized by prominent proliferation of Brunner’s gland without cellular atypia. The presence of a mixture of mesenchymal tissues, such as fatty tissue, thick bands of smooth muscles, and Brunner’s glands are features of Brunner’s gland hamartoma. Brunner’s gland adenoma is defined by the presence of cellular atypia or dysplasia of glandular component[15,16].

Benign proliferations in Brunner’s glands account for 5%–10% of benign duodenal masses and < 1% of primary small intestinal tumors[2,13,14,17]. BGH was found in 0.3% among patients who undergo upper gastrointestinal endoscopy[2,17]. These proliferative lesions may manifest as solitary or multiple nodules, appearing as sessile or polypoid masses in most cases. They are usually found in the proximal duodenum[3,15,18]. They are mostly < 20 mm[3,17]. However, much larger lesions measuring up to 120 mm have been reported[19]. Clinically, most BGHs are asymptomatic, incidentally found in patients at the age of 50–60 years[2,3,15,17]. In case of symptomatic BGH, the most common presentation is GI bleeding, either hematemesis or melena[4,5], although < 15 cases showing acute hemorrhage have been reported[20,21]. Rarely, BGHs can cause biliary obstruction and pancreatitis[22]. Treatment by either surgical resection or endoscopic polypectomy is required for symptomatic patients. Our patient showed a huge pedunculated mass, which is a rare presentation of duodenal BGH. In addition, our patient presented with recurrent upper GI bleeding, which is also a rare presentation of duodenal BGH, although it was not definitely clear if the BGH was the only bleeding source because esophagogastroduodenoscopy showed no stigmata of recent bleeding, such as clearly exposed vessels and active bleeding with or without blood clots. Because the esophagogastroduodenoscopy showed ulcers at the surface of the BGH, we suggested the BGH as a possible bleeding source.

LiPH of the pancreas is an extremely rare entity of unknown etiology. The replacement of the entire pancreas with increasing amounts of adipose tissue and the consequent enlargement of the pancreas was first described by Hantelmann in 1931[10]. Fewer than 100 cases of LiPH of the pancreas have been reported worldwide[11,23-29]. In a previous case series and literature review, the mean patient age was 41 years (range, 6 d to 80 years), with no difference in gender distribution[23]. The affected sites included the entire pancreas (20 cases), body and pancreatic tail (3 cases), pancreatic head (4 cases) and uncinate process (1 case)[28]. In symptomatic patients, the most common symptoms were exocrine pancreatic dysfunction such as chronic diarrhea and signs of chronic pancreatitis[26,30]. In another case, the disease caused an obstruction of the bile duct and required surgical treatment by a hepaticojejunostomy.

LiPH of the pancreas is often discovered and suspected by CT and MRI[23,31]. CT scan can accurately facilitate the diagnosis of fatty lesions such as lipoma based on low attenuation signals of 50 to 100 HU[32]. In our case, the lesion showed 90.6 HU on the CT scan. Besides the CT attenuation signals, the entire pancreas was substantially replaced with fat and no abnormality of the pancreatic duct was observed. In addition, obstruction of the main pancreatic duct was not found on CT and MRI in our patient. All these radiological findings were compatible with the diagnosis of LiPH of the pancreas. When making a differential diagnosis of LiPH of the pancreas, the following disorders need to be considered: obesity, diabetes, age-related pancreatic fat infiltration, and liposarcoma[26]. Our patient was diagnosed with LiPH of the pancreas based on the above radiological findings together with typical histological features of percutaneous biopsy specimens.

Although there is a suggestion that LiPH of the pancreas might be caused by viral infection and abnormal metabolism[33], the specific etiology remains unknown due to the small number of cases. Several previous reports have suggested a possible correlation between LiPH of the pancreas and hepatic illness[11,26,34]. Coexisting diseases included liver cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis[35], suggesting the possibility that chronic liver injury might influence the development of LiPH of the pancreas[36]. In our case, the patient had segmental biliary ectasia, which also supports the possible association between LiPH of the pancreas and hepatic illness.

The most important educational point of this case may be the usefulness of combined examination of esophagogastroduodenoscopy and radiological studies such as CT and MRI in patients with melena. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy can evaluate lesions of the esophagus, stomach and duodenum. CT and MRI can detect abnormalities in the small intestine. In addition, if a patient shows a submucosal mass by esophagogastroduodenoscopy, CT and MRI can provide further information about the features of the mass, thereby narrowing the list of possible diagnoses. In our case, CT and MRI showed marked duodenal wall thickening suggestive of a possible source of bleeding, although they could not specifically diagnose the lesion. Furthermore, CT and MRI could detect LiPH of the pancreas that was associated with BGH in our case.

An interesting feature of our patient was the coexistence of LiPH of the pancreas and a huge pedunculated BGH of the duodenum. Because each condition is so rare, the probability of purely coincidental coexistence of both conditions may be extremely low, although the direct etiopathogenic association between these two diseases is unclear. As CT and MRI showed direct infiltration of LiPH into the duodenal wall, we suggest some mechanical influence by the infiltrated fatty tissue might have contributed to the development and/or growth of duodenal BGH. Further research is necessary to clarify the underlying mechanism of association between LiPH of the pancreas and other diseases.

There were some limitations to our case report. First, the patient did not undergo surgical treatment for a large BGH that showed bleeding. Because the patient showed recurrent bleeding, we should have persuaded the patient to undergo surgery for prevention of recurrent, massive bleeding in the future. In addition, surgery could have shown the etiopathogenic association of BGH and LiPH of the pancreas by detailed histological examination of the surgically resected specimen. Second, we cannot confidently conclude that BGH was the only bleeding source because the recent bleeding stigma was not evident at the BGH of our patient. Evaluation of the small intestine should have been performed to see if there were other possible bleeding sources in the small intestine. Finally, we did not show the follow-up clinical course of this patient. Thus, we could not show the long-term clinical course of the patient with two rare conditions.

CONCLUSION

We report an extremely rare case with coexisting LiPH of the pancreas and a huge pedunculated BGH of the duodenum that presented with upper GI bleeding. This case report highlights special features of both LiPH and BGH and suggests that LiPH of the pancreas may infiltrate the duodenal wall and potentially coincide with duodenal pathologies.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Informed written consent was obtained from the patients for the publication of these reports and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement: There is no conflict of interest to declare.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: June 6, 2021

First decision: June 25, 2021

Article in press: September 19, 2021

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Viet Nam

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Asadzade Aghdaei H S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Kerr C P-Editor: Guo X

Contributor Information

Long Cong Nguyen, Gastroenterology and Hepatology Center, Bach Mai Hospital, Hanoi 10000, Viet Nam; Department of Gastroenterology, School of Medicine and Pharmacy, Vietnam National University Hanoi, Hanoi 10000, Viet Nam. nguyenconglongbvbm@gmail.com.

Khanh Truong Vu, Gastroenterology and Hepatology Center, Bach Mai Hospital, Hanoi 10000, Viet Nam; Department of Gastroenterology, School of Medicine and Pharmacy, Vietnam National University Hanoi, Hanoi 10000, Viet Nam.

Trang Thi Thuy Vo, Gastroenterology and Hepatology Center, Bach Mai Hospital, Hanoi 10000, Viet Nam.

Chau Ha Trinh, Radiology Center, Bach Mai Hospital, Hanoi 10000, Viet Nam.

Tan Dang Do, Radiology Center, Bach Mai Hospital, Hanoi 10000, Viet Nam.

Ngoc Thi Van Pham, Gastroenterology and Hepatology Center, Bach Mai Hospital, Hanoi 10000, Viet Nam.

Tuyen Van Pham, Pathology Center, Bach Mai Hospital, Hanoi 10000, Viet Nam.

Thanh Tuan Nguyen, Pathology Center, Bach Mai Hospital, Hanoi 10000, Viet Nam.

Hiep Canh Nguyen, Pathology Center, Bach Mai Hospital, Hanoi 10000, Viet Nam; Department of Human Pathology, Kanazawa University Graduate School of Medicine, Kanazawa 920-8640, Japan.

Jeong-Sik Byeon, Department of Gastroenterology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul 05505, South Korea.

References

- 1.Peetz ME, Moseley HS. Brunner's gland hyperplasia. Am Surg. 1989;55:474–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu M, Li H, Wu Y, An Y, Wang Y, Ye C, Zhang D, Ma R, Wang X, Shao X, Guo X, Qi X. Brunner's Gland Hamartoma of the Duodenum: A Literature Review. Adv Ther. 2021;38:2779–2794. doi: 10.1007/s12325-021-01750-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou SR, Ullah S, Liu YY, Liu BR. Brunner's gland adenoma: Lessons learned for 48 cases. Dig Liver Dis. 2021;53:134–136. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2020.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chattopadhyay P, Kundu AK, Bhattacharyya S, Bandyopadhyay A. Diffuse nodular hyperplasia of Brunner's gland presenting as upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Singapore Med J. 2008;49:81–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wani ML, Malik AA, Malik RA, Irshad I. Brunner's gland hyperplasia: an unusual cause of gastrointestinal bleeding. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2011;22:419–421. doi: 10.4318/tjg.2011.0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maruo M, Tahara T, Inoue F, Kasai T, Saito N, Aoi K, Takeo M, Sumimoto K, Yamashina M, Murata M, Koyabu M, Wakamatsu T, Yamashiki N, Nishio A, Okazaki K, Naganuma M. A giant Brunner gland hamartoma successfully treated by endoscopic excision followed by transanal retrieval: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021;100:e25048. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000025048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bakir MA, AlYousef MY, Alsohaibani FI, Alsaad KO. Brunner's glands hamartoma with pylorus obstruction: a case report and review of literature. J Surg Case Rep. 2020;2020:rjaa191. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjaa191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meltser E, Federici M, Cooper R 2nd, Capanescu C, Behling KC. Fatal Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage in a Patient with Brunner's Gland Hyperplasia. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2017;11:411–415. doi: 10.1159/000477717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yadav D, Hertan H, Pitchumoni CS. A giant Brunner's gland adenoma presenting as gastrointestinal hemorrhage. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:448–450. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200105000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hantelmann W. Fettsucht und Atrophie der Bauchspeicheldrüse bei Jugendlichen. Virchows Arch path Anat . 1931:282: 630–642. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegler DI. Lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas associated with chronic pulmonary suppuration in an adult. Postgrad Med J. 1974;50:53–55. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.50.579.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krause WJ. Brunner's glands: a structural, histochemical and pathological profile. Prog Histochem Cytochem. 2000;35:259–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peloso A, Viganò J, Vanoli A, Dominioni T, Zonta S, Bugada D, Bianchi CM, Calabrese F, Benzoni I, Maestri M, Dionigi P, Cobianchi L. Saving from unnecessary pancreaticoduodenectomy. Brunner's gland hamartoma: Case report on a rare duodenal lesion and exhaustive literature review. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2017;17:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2017.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Botsford TW, Crowe P, Crocker DW. Tumors of the small intestine. A review of experience with 115 cases including a report of a rare case of malignant hemangio-endothelioma. Am J Surg. 1962;103:358–365. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(62)90226-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim K, Jang SJ, Song HJ, Yu E. Clinicopathologic characteristics and mucin expression in Brunner's gland proliferating lesions. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:194–201. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montgomery EA, Yantiss RK, Snover DC, Tang LH. Hamartomatous polyps, heterotopias, unclassified polyps, and tumor-like lesions. AFIP Atlas of Tumor Pathology Series 4 Tumor of the Intestines. AFIP Atlas of Tumor Pathology AFIP Atlas of Tumor Pathology Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology; 2017: 21-62. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jung SH, Chung WC, Kim EJ, Kim SH, Paik CN, Lee BI, Cho YS, Lee KM. Evaluation of non-ampullary duodenal polyps: comparison of non-neoplastic and neoplastic lesions. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5474–5480. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i43.5474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feyrter F. Über Wucherungen der Brunnerschen Drüsen. Virchows Arch path Anat . 1934:293: 509–526. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rana R, Sapkota R, Kc B, Hirachan A, Limbu B. Giant Brunner's Gland Adenoma Presenting as Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in 76 Years Old Male: A Case Report. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2019;57:50–52. doi: 10.31729/jnma.4013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michel LA, Ballet T, Collard JM, Bradpiece HA, Haot J. Severe bleeding from submucosal lipoma of the duodenum. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1988;10:541–545. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198810000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tung CF, Chow WK, Peng YC, Chen GH, Yang DY, Kwan PC. Bleeding duodenal lipoma successfully treated with endoscopic polypectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:116–117. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.113916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayoral W, Salcedo JA, Montgomery E, Al-Kawas FH. Biliary obstruction and pancreatitis caused by Brunner's gland hyperplasia of the ampulla of Vater: a case report and review of the literature. Endoscopy. 2000;32:998–1001. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altinel D, Basturk O, Sarmiento JM, Martin D, Jacobs MJ, Kooby DA, Adsay NV. Lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas: a clinicopathologically distinct entity. Pancreas. 2010;39:392–397. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181bd2923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Izumi S, Nakamura S, Tokumo M, Mano S. A minute pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas. JOP. 2011;12:464–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamura M, Katada N, Sakakibara A, Okumura N, Kato E, Takeichi M, Kondo T, Mano H. Huge lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas. Am J Gastroenterol. 1979;72:171–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olsen TS. Lipomatosis of the pancreas in autopsy material and its relation to age and overweight. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand A. 1978;86A:367–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1978.tb02058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nema D, Arora S, Mishra A. Lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of pancreas with coexisting chronic calcific pancreatitis leading to malabsorption due to exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. Med J Armed Forces India. 2016;72:S213–S216. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimada M, Shibahara K, Kitamura H, Demura Y, Hada M, Takehara A, Nozaki Z, Sasaki M, Konishi K, Maeda Y. Lipomatous Pseudohypertrophy of the Pancreas Taking the Form of Huge Massive Lesion of the Pancreatic Head. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2010;4:457–464. doi: 10.1159/000321989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Labied M, Tabakh H, Guezri H, Siwane A, Touil N, Kacimi O, Chikhaoui N. A Rare Case of Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2021;8:002556. doi: 10.12890/2021_002556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reddy OJ, Gafoor JA, Reddy GM, Prasad PO. Total pancreatic lipomatosis: A rare presentation. J NTR Univ Health Sci. 2015;4:272. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yasuda M, Niina Y, Uchida M, Fujimori N, Nakamura T, Oono T, Igarashi H, Ishigami K, Yasukouchi Y, Nakamura K, Ito T, Takayanagi R. A case of lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas diagnosed by typical imaging. JOP. 2010;11:385–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waligore MP, Stephens DH, Soule EH, McLeod RA. Lipomatous tumors of the abdominal cavity: CT appearance and pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1981;137:539–545. doi: 10.2214/ajr.137.3.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Høyer A. Lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas with complete absence of exocrine tissue. J Pathol Bacteriol . 1949;61:93–100. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Masuda A, Tanaka H, Ikegawa T, Matsuda T, Shiomi H, Takenaka M, Matsuki N, Kakuyama S, Sugimoto M, Fujita T, Arisaka Y, Hayakumo T, Hara S, Azuma T, Kutsumi H. A case of lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas diagnosed by EUS-FNA. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2012;5:282–286. doi: 10.1007/s12328-012-0318-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flohr T, Bonatti H, Shumaker N, Diaz F, Berg C, Sanfey H, Pruett T, Sawyer R, Schmitt T. Liver transplantation in a patient with primary sclerosing cholangitis suffering from lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas. Transpl Int. 2008;21:89–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2007.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuroda N, Okada M, Toi M, Hiroi M, Enzan H. Lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas: further evidence of advanced hepatic lesion as the pathogenesis. Pathol Int. 2003;53:98–101. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2003.01437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]