Abstract

Single-atom catalysts (SACs) have been applied in many fields due to their superior catalytic performance. Because of the unique properties of the single-atom-site, using the single atoms as catalysts to synthesize SACs is promising. In this work, we have successfully achieved Co1 SAC using Pt1 atoms as catalysts. More importantly, this synthesis strategy can be extended to achieve Fe and Ni SACs as well. X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) results demonstrate that the achieved Fe, Co, and Ni SACs are in a M1-pyrrolic N4 (M= Fe, Co, and Ni) structure. Density functional theory (DFT) studies show that the Co(Cp)2 dissociation is enhanced by Pt1 atoms, thus leading to the formation of Co1 atoms instead of nanoparticles. These SACs are also evaluated under hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER), and the nature of active sites under HER are unveiled by the operando XAS studies. These new findings extend the application fields of SACs to catalytic fabrication methodology, which is promising for the rational design of advanced SACs.

Subject terms: Renewable energy, Electrocatalysis, Catalyst synthesis

Synthesizing single-atom catalysts through a general method presents a great challenge. Here the authors report that Fe, Co and Ni single-atom catalysts can be obtained using pre-located isolated Pt atoms as the catalyst and identify the role of Pt single atoms in the synthesis process.

Introduction

Single-atom catalysts (SACs)1 have attracted considerable interest due to their superior catalytic activity and unique selectivity towards different chemical reactions, including CO oxidation1,2, hydrogenation3, dehydrogenation4,5, and electrochemical reactions6–8. Recently, the application of SACs has been widely extended to various research areas9–14 including energy storage systems like Li-S batteries15, enzyme catalysis16, photocatalysis17, and even cellular NO sensor18. Therefore, SACs are continuously showing great potentials for wide applications.

The most significant distinction between SACs and other types of catalysts is their unique single-atom-site, which both increases the atom utilization efficiency and tailors the interaction between the reactant and metal atoms through the adsorption and activation process. For example, Yan et al. reported the Pd1/graphene SACs showed a high butane selectivity in the hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene, where the adsorption of 1,3-butadiene on Pd1 was mainly in a mono-π mode, which differs from that on Pd bulk3. Duchesne and co-workers showed that the Pt single atoms on Au nanoparticles (NPs) exhibited superior catalytic performance in formic acid oxidation. Such a high activity of Pt4Au96 is ascribed to the weakened CO adsorption on single and few Pt atoms than that on Pt bulk19. Li and co-workers demonstrated that the Pt1/Co3O4 exhibited a much weaker H2 adsorption energy than Pt bulk, thus leading to its high catalytic performance in the dehydrogenation of ammonia borane5.

However, because of their highly un-saturated coordination environment, heterogeneously supported single atoms possess a dramatically increased surface-free energy, which can lead to their aggregation into NPs, particularly at high metal loadings. Recently, some strategies have been developed to achieve relatively high-loading SACs. These methods include zeolite or mesoporous carbon to stabilize single atoms through a confinement strategy20–23, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) to achieve SACs through high-temperature pyrolysis24, metal NPs to achieve SACs through high-temperature migration25,26, and a high-temperature shock wave treatment to achieve high loading SACs27. However, there are yet some restrictions on these newly developed methods such as general applicability. Therefore, developing a general approach for the synthesis of various types of SACs is highly desired.

Atomic layer deposition (ALD), a sequential surface reaction relying on a self-limiting process is used to synthesize non-noble single atoms such as Fe and Co28,29. Unfortunately, it results in a low metal loading and the formation of NPs, especially on carbon-based supports due to the high dissociation barrier and predominantly physical adsorption of metal precursors28–31. Therefore, a new reasonable route to produce SACs by ALD may be achieved by lowering the dissociation energy of the ALD precursor. For instance, this high dissociation energy might be strongly reduced on a metal surface31–33. Accordingly, the use of metal single atoms as the catalyst to facilitate the dissociation of ALD precursors to synthesize SACs would be very promising. To the best of our knowledge, this new SACs producing strategy that uses surface single atoms as the catalysts has never been reported. Moreover, the ALD method is feasible to obtain single atoms on various supports, which not only provides a new way to achieve SACs with dual atomic sites but also extends the application fields of SACs to the catalytic fabrication methodology.

In this work, we firstly verified the strategy by using supported Pt single atoms on N-doped carbon nanosheets (Pt1/NCNS) as the catalyst to synthesize Co SAC through ALD. X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) results reveal singly dispersed Co1 atoms. Interestingly, the Pt1 atoms are still atomically dispersed after Co deposition, as confirmed by XAS and high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM). Furthermore, we also show that this synthesis strategy is general and can also be easily extended to achieve Fe and Ni SACs. X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) simulation and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) analysis results demonstrate that the achieved Co, Fe, and Ni SACs are in a M1-pyrrolic-N4 structure (M=Fe, Co, and Ni). Density functional theory (DFT) calculations show that Pt1 atoms promote the dissociation of Co(Cp)2 into CoCp and Cp fragments. The Co(Cp) product further deposited on the substrate through strong chemisorption, thus leading to a higher metal loading and formation of Co1 atoms. These SACs were evaluated under hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and the nature of single-atom sites are unveiled by the operando XAS studies. Moreover, in the oxygen evolution reaction (OER), the Ni1 SAC showed much higher activity than Fe1 and Co1 SACs, which is in line with the DFT predictions.

Results and discussion

Direct fabrication of Pt and Co single atoms on NCNS using ALD

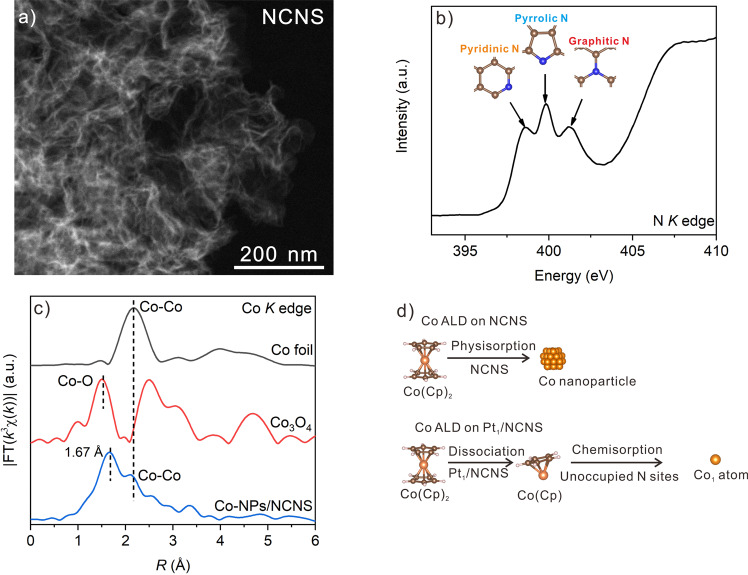

Graphene like NCNS (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1) was firstly achieved using C3N4 as the template and glucose as the carbon source34. N K-edge XANES results indicate that there are various types of N species including pyridinic, pyrrolic, and graphitic N on NCNS (Fig. 1b)35. According to the literature, the N defects can coordinate with metal species and form a stable SAC7. Therefore, the NCNS substrate shows high potential for the synthesis of SACs. After performing one cycle of Pt ALD on NCNS, well-dispersed Pt single atoms were confirmed by HAADF-STEM (Supplementary Fig. 2) and XAS results (Supplementary Fig. 3)36. The loading of Pt is as high as 2.0 wt% based on the inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES) results.

Fig. 1. Characterizations for pristine NCNS, Co-NPs/NCNS, and proposed synthesis strategies for Co SAC.

a HAADF-STEM image of NCNS. b XANES of NCNS at N K edge. c FT-EXAFS of Co-NPs/NCNS, as well as Co foil and Co3O4 reference at Co K edge, respectively. d Assumption of the Co ALD process on pristine NCNS and Pt1/NCNS. The white, brown, blue, and orange spheres represent H, C, N, and Co, respectively.

Since the NCNS shows great potential to support Pt1 atoms, it has the possibility to act as a suitable substrate for other types of SACs. Using ALD, we performed one cycle of Co ALD on NCNS with Co(Cp)2 and O2 as the precursors. However, unlike the formation of Pt1 atoms, we found obvious Co NPs/clusters in HAADF-STEM (Supplementary Fig. 4a) and Co-Co coordination from the EXAFS results at the Co K edge (Fig. 1c), indicating the formation of Co NPs (Co-NPs/NCNS). Besides the formation of Co NPs, we also noticed a very low metal loading of Co (0.5 wt%). Such a low loading of Co indicates limited physisorption after the dose of Co(Cp)2 precursor, and the unreacted Co(Cp)2 would be purged away by N2 as illustrated in (Supplementary Fig. 5), leading to a low effective Co deposition30. Unfortunately, the weak adsorption effect of Co(Cp)2 on NCNS will form Co NPs due to the weak interaction between Co species and substrate when O2 is introduced. Therefore, the direct utilization of the Co ALD process to produce Co single atoms on NCNS is not practical.

Synthesizing Co, Fe, and Ni SACs using pre-located isolated Pt1 atoms

Inspired by previous research, the dissociation of Co(Cp)2 will be enhanced on the metal surface37. In our system, the Pt single atoms are easy to achieve, and the Pt-based catalysts are active in many chemical reactions. Therefore, the singly dispersed Pt1 atoms may have a similar ability and are likely capable to decrease the dissociation energy of Co(Cp)2, which may increase the Co loading and more importantly to achieve Co single atoms. With this idea in mind, we firstly conducted one cycle of Pt ALD on NCNS to achieve Pt1/NCNS and followed up with one cycle of Co ALD to verify our assumption (Fig. 1d). After performing one cycle of Co ALD on Pt1/NCNS substrate, the Co K edge EXAFS of this sample exhibits only one single peak at 1.57 Å (Fig. 2a), which can be attributed to the first shell of Co-C/N/O coordination. Meanwhile, the coordination of Co-Co is negligible, indicating that the Co species mostly exist as single atoms from the new synthesis strategy. In the following parts, this sample is denoted as Co1Pt1/NCNS.

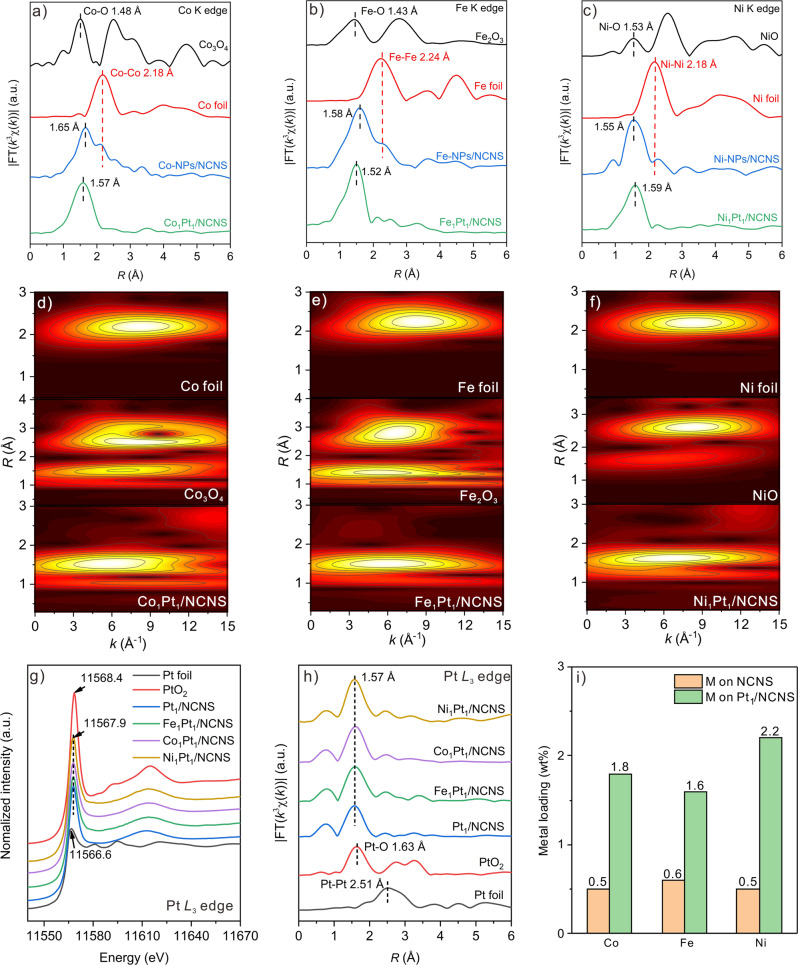

Fig. 2. XAS characterizations for M1Pt1/NCNS catalysts.

a–c Radial distribution curve from FT-EXAFS of Co-NPs/NCNS, Co1Pt1/NCNS, Fe-NPs/NCNS, Fe1Pt1/NCNS, Ni-NPs/NCNS, and Ni1Pt1/NCNS, respectively, as well as their corresponding foil and oxide reference at Co, Fe, and Ni K edges. d–f Wavelet-transformed spectra of Co1Pt1/NCNS, Fe1Pt1/NCNS, Ni1Pt1/NCNS, as well as their corresponding foil and oxide reference at Co, Fe, and Ni K edges. g and h XANES and FT-EXAFS of Pt1/NCNS, Co1Pt1/NCNS, Fe1Pt1/NCNS, and Ni1Pt1/NCNS, respectively, as well as Pt foil and PtO2 reference at Pt L3 edge. i ICP-OES results of M (Fe, Co, and Ni) metal loadings.

In order to further extend the application of this synthesis strategy to other SACs such as Fe and Ni, we have chosen to use Fe and Ni ALD precursors with similar chemical structures as that of Co, i.e., ferrocene and nickelocene, respectively. Similarly, Fe and Ni single atoms also cannot be achieved by ALD on pristine NCNS as revealed by Fe-Fe and Ni-Ni coordination in the EXAFS (Fig. 2b, c) and TEM results (Supplementary Fig. 4). In contrast, the Fe-Fe and Ni-Ni coordination are significantly depressed when performing one cycle of Fe and Ni ALD on Pt1/NCNS (Fe1Pt1/NCNS and Ni1Pt1/NCNS) (Fig. 2b, c). Wavelet-transform EXAFS results further verified the atomically dispersed Co, Fe, and Ni single atoms, which differs from that of their foil and oxide (Fig. 2d, f).

More interestingly, the Pt L3 edge XANES (Fig. 2g) and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) (Supplementary Fig. 6) results show inconspicuous differences, indicating the electronic properties of Pt on these M1Pt1/NCNS (M=Fe, Co, and Ni) samples are close to that on Pt1/NCNS. Pt L3 edge EXAFS results further confirm the stable local structure of the Pt1 atom (Fig. 2h). Typical EXAFS fitting on Co1Pt1/NCNS at Pt L3 edge also demonstrates the unchanged atomic nature of Pt single atoms (Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 1). These results indicate that the Pt1 atoms are still atomically dispersed after the deposition of Co, Fe, and Ni. This observation provides strong evidence that the Pt1 atoms only act as the catalyst, while they change the deposition process of Co, Fe, and Ni, but does not lose the atomic dispersion or form a Pt-Co/Fe/Ni cluster, because of the lack of metal-metal coordination in Pt L3, Fe, Co, and Ni K edges EXAFS results. Subsequently, we examined the Co loading through ICP-OES after performing one cycle of Co ALD on pristine NCNS and Pt1/NCNS (Fig. 2i). The ICP-OES results show that the Co loading of Co1Pt1/NCNS (1.8 wt%) is more than three times higher than that of Co-NPs/NCNS (0.5 wt%). Similar results are also observed on Fe and Ni, showing low Fe and Ni loadings on Fe-NPs/NCNS and Ni-NPs/NCNS (0.6 and 0.5 wt%) but much higher on Fe1Pt1/NCNS and Ni1Pt1/NCNS (1.6 and 2.2 wt%), respectively. These results unambiguously demonstrate that the Pt1 atoms change the adsorption model of M precursors to predominantly chemisorption, which promotes the degree of effective deposition. However, when the M ALD was performed on pristine NCNS, physisorption is dominant, thus leading to a low metal loading because of less effective deposition.

Morphology of M1Pt1/NCNS catalysts

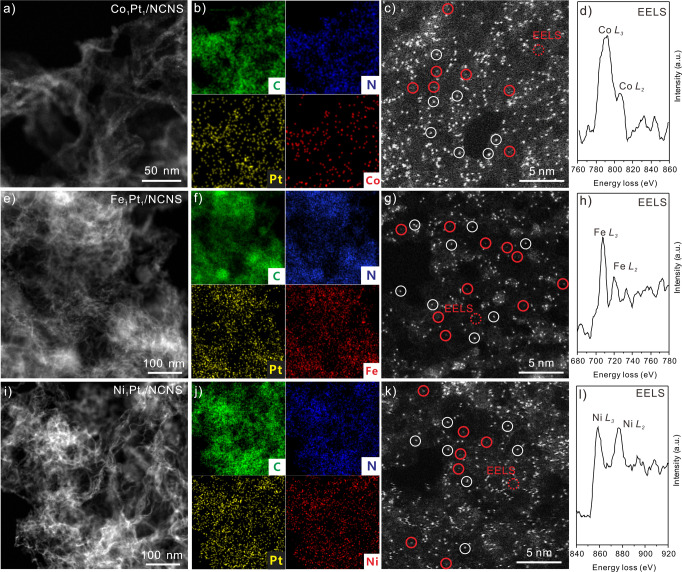

The morphology of M1Pt1/NCNS catalysts is characterized by HAADF-STEM. As shown in Fig. 3a, e, i, no observable Pt or M NPs can be found at low magnification. Energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) mapping results show the Pt and M elements are well-dispersed on the NCNS substrate (Fig. 3b, f, j and Supplementary Figs. 8 to 10), indicating their uniform dispersion and high density. At high magnification, high-density bright Pt single atoms (white circles) can be found on Co1Pt1/NCNS (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 8f), Fe1Pt1/NCNS (Fig. 3g and Supplementary Fig. 9f), and Ni1Pt1/NCNS (Fig. 3k and Supplementary Fig. 10f). All the visible Pt atoms are singly dispersed without any obvious clusters or NPs. Meanwhile, some isolated atoms with less brightness (red circles) were also found to reside nearby the bright Pt1 atoms, which can be assigned to Fe, Co, and Ni single atoms due to their lower Z-contrast. Furthermore, when the electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) was measured at the atoms with less brightness on Co1Pt1/NCNS, the signals of Co L2 and L3 could also be detected (Fig. 3d), confirming the existence of Co1 atoms. Similar results can be also found on Fe1Pt1/NCNS (Fig. 3h) and Ni1Pt1/NCNS (Fig. 3i). Based on the HAADF-STEM results, the Fe, Co, and Ni-Pt pairs are absent. Taken together, the EXAFS and HAADF-STEM results demonstrate the single-atom nature of both Pt and M atoms on NCNS.

Fig. 3. Morphology of M1Pt1/NCNS catalysts.

HAADF-STEM images of Co1Pt1/NCNS (a), Fe1Pt1/NCNS (e), and Ni1Pt1/NCNS (i) at low resolution and corresponding EDX mapping (b, f, and j). HAADF-STEM images on Co1Pt1/NCNS (c), Fe1Pt1/NCNS (g), and Ni1Pt1/NCNS (k) samples. The white circles highlight the Pt single atoms. The red circles highlight the Co, Fe, and Ni single atoms, respectively. d, h, and l Corresponding EELS spectra at the location of red dash circle in c, g, and k.

Structure identification of M SACs

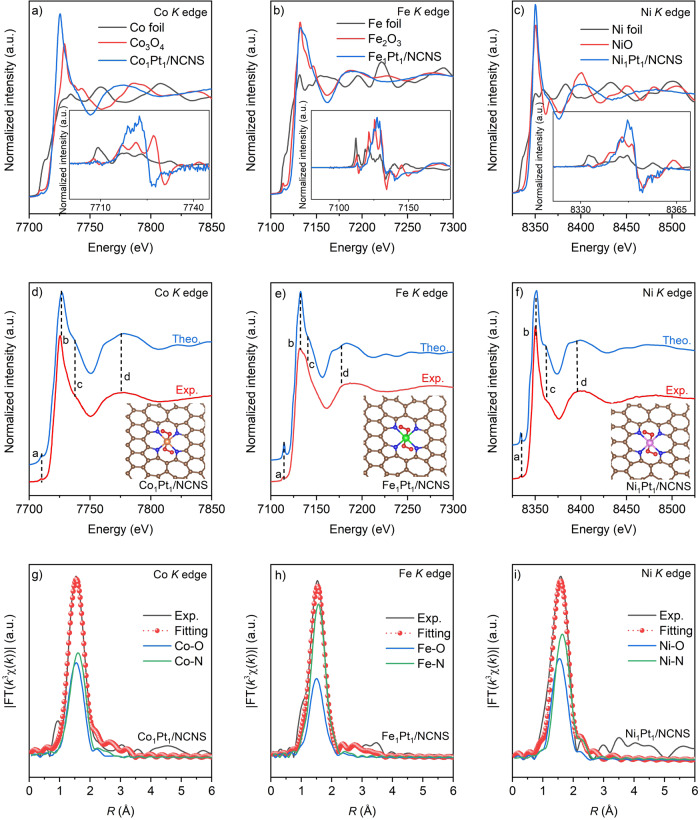

Using this synthesis strategy, we have successfully achieved Co, Fe, and Ni SACs. Unveiling the local structure of these SACs is critical to understand the synthesis mechanism and their catalytic applications. XANES spectroscopy is very sensitive to the local geometric structure of the photon-absorbing atom, which provides a better option to understand the local atomic structure. As shown in Fig. 4a to c, the Co1Pt1/NCNS, Fe1Pt1/NCNS, and Ni1Pt1/NCNS at Co, Fe, and Ni K edge XANES spectra, respectively, show significant differences from their corresponding foil and oxide references. We also notice that the XANES spectra of Co1Pt1/NCNS, Fe1Pt1/NCNS, and Ni1Pt1/NCNS are nearly identical, indicating a similar local coordination environment of M1Pt1/NCNS catalysts. This can be delineated since the k-dependent absorber phase shift of Fe, Co, and Ni, adjacent in the periodic table, is very similar. Taking the first derivative XANES of M1Pt1/NCNS, the energy position of the point of first inflection suggests that the oxidation states of Fe, Co, and Ni are close to +3, +2, and +2, respectively. These observations are perfectly in line with the XPS results (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Fig. 4. Identification of the local structure of M1Pt1/NCNS catalysts.

a–c The experimental K-edge XANES spectra and first derivative curves (insets) of M1Pt1/NCNS and references samples. d–f Comparison between the experimental K-edge XANES spectra of M1Pt1/NCNS and the simulated spectra. Some of the main features reproduced are highlighted at points “a” to “d”. Fitting results of the k3-weighted FT spectrum of M1Pt1/NCNS at Co (g), Fe (h), and Ni (i) K edges. The white, brown, blue, red, orange, green, and pink spheres represent H, C, N, O, Co, Fe, and Ni, respectively.

Focusing on the Co1Pt1/NCNS catalyst, we first compared the modeling XANES result based on a recently reported Co-C4-O2 type Co1 atom on graphene using ALD (Supplementary Fig. 12a)38. Significant differences can be observed between the theoretical simulated XANES and experimental results, indicating the necessity to consider the critical role of N atoms. We then further compared the reported pyridinic-N4-based Co1-N4 structure, which still shows the obvious difference with our experimental XANES results (Supplementary Fig. 12b), suggesting the existence of defects in this model as well. Then we progressively add one and two end-on oxygen moieties along the axial direction of the pyridinic Co1-N4 structure (Supplementary Fig. 12c, d). Although parts of the experimentally resolved features can be reproduced and achieve a satisfactory agreement with the Co1Pt1/NCNS Co K edge XANES results, the short Co-N bonding distance (less than 1.90 Å) disagrees with our EXAFS results (Fig. 2a). Considering that there is a large proportion of pyrrolic-N in the NCNS support, the possibility of a pyrrolic-N4 type Co1-N4 structure cannot be ruled out. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 12e, the simulated XANES result of pyrrolic-N4-based Co1-N4 showed much better conformity than the pyridinic-N4 structure. We then further added one molecule of dioxygen with end on coordination on Co1 atom, the features from “b” to “d” are well reproduced but the pre-edge feature “a” is exaggerated (Supplementary Fig. 12f). However, when we added another molecule of dioxygen on the Co1 atom at the opposite side, all the features from “a” to “d” can be correctly reproduced (Fig. 4d). Similarly, the simulated 2O2-Fe1-pyrrolic N4 and 2O2-Ni1-pyrrolic N4 XANES spectra (Fig. 4e, f) show the most satisfactory results comparing with other DFT optimized structures (Supplementary Figs. 13 and 14). It is important to note, this is the first time that general M1-pyrrolic N4 type SACs can be achieved using ALD, as this type of SACs is usually achieved through high-temperature pyrolysis and ball-milling methods39,40. Bedsides the above XANES simulation, we also carried out the EXAFS fitting and the results consistently demonstrate the 2O2-M1-pyrrolic N4 moiety (Fig. 4g to i, Supplementary Figs. 15 to 18, and Table 1). It is worth noting that the EXAFS results perfectly match the DFT results (Supplementary Table 2). In summary, a close local structure of Co1Pt1/NCNS, Fe1Pt1/NCNS and Ni1Pt1/NCNS from simulated XANES and EXAFS fitting results strongly suggest the same deposition mechanism for Co, Fe, and Ni ALD on Pt1/NCNS, which indicates that this synthesis strategy can be a universal approach to achieve M1-pyrrolic N4 type SACs using Pt1 atoms.

Table 1.

Structural parameters of the M1Pt1/NCNS (M=Fe, Co, and Ni), foil, and oxide references extracted from quantitative EXAFS curve-fittings at Co, Fe, and Ni K edges.

| Sample | Path | CNs | R (Å) | σ2 (10−3Å2) | ΔE0 (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co foil | Co-Co | 12.0 | 2.49 | 6.1 | 6.9 |

| Co3O4 | Co-O | 4.0 | 1.91 | 1.7 | 1.0 |

| Co1Pt1/NCNS | Co-O | 2.0 | 1.98 | 3.3 | 2.2 |

| Co-N | 4.0 | 2.08 | 6.4 | ||

| Fe foil | Fe-Fe | 8.0 | 2.46 | 5.3 | 5.3 |

| Fe-Fe | 6.0 | 2.85 | |||

| Fe2O3 | Fe-O | 6.0 | 1.93 | 10.0 | −6.0 |

| Fe1Pt1/NCNS | Fe-O | 2.2 | 1.95 | 2.0 | −4.2 |

| Fe-N | 4.2 | 2.02 | 2.9 | ||

| Ni foil | Ni-Ni | 12.0 | 2.48 | 6.1 | 7.4 |

| NiO | Ni-O | 6.0 | 2.05 | 4.2 | −3.7 |

| Ni1Pt1/NCNS | Ni-O | 2.2 | 1.99 | 1.5 | 2.1 |

| Ni-N | 4.2 | 2.11 | 2.5 |

CNs coordination numbers, R bonding distance, σ2 Debye-Waller factor, ΔE0 inner potential shift. Errors in the fitting parameters are CN ± 20%, R ± 0.02, σ2 ± 20%, and ΔE0 ± 3.0.

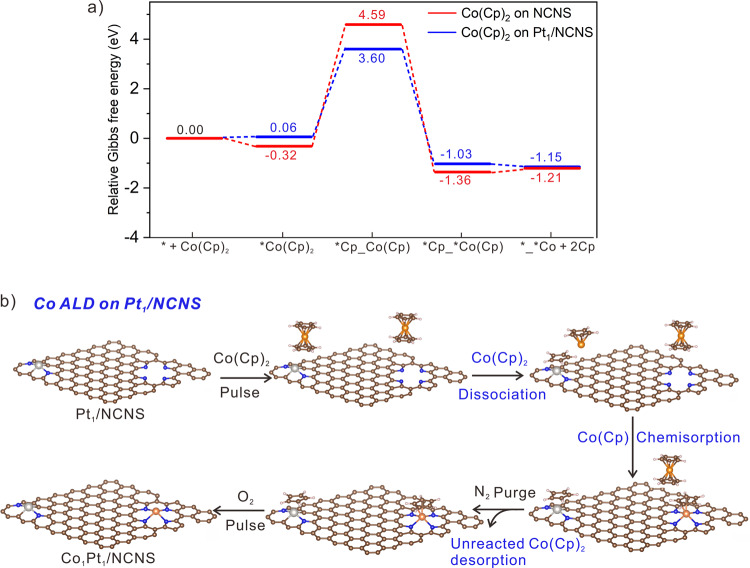

Theoretical understanding of deposition process

Having resolved the structures of M1Pt1/NCNS and Pt1/NCNS, we carried out DFT calculations to elucidate the deposition mechanism. Considering the similar structure of Co, Fe, and Ni ALD precursors and local structures of Co1Pt1/NCNS, Fe1Pt1/NCNS, and Ni1Pt1/NCNS catalysts, typical Co ALD process is chosen for the following theoretical investigation. As revealed by the calculated Gibbs free energies shown in Fig. 5a, the Co(Cp)2 has moderate adsorption (ΔGad = −0.32 eV) but very high dissociation energy (ΔGde = 4.91 eV) on the pristine NCNS. Therefore, the physisorption of Co(Cp)2 should be dominant on pristine NCNS. This physically and weakly adsorbed Co(Cp)2 will lead to a low metal loading from inefficient deposition (Fig. 2i and Supplementary Fig. 5). Owing to the weak physisorption, Co species will easily aggregate because of the lack of strong chemical bonding with the substrate. Therefore, Co NPs were observed in the direct Co ALD process on NCNS (Fig. 1c). However, when Pt1 atoms are involved in the Co ALD process, the deposition model differs considerably. Although the adsorption of Co(Cp)2 on Pt1 atom is slightly weaker (ΔGad = +0.06 eV), the dissociation energy of Co(Cp)2 is reduced to ΔGde = 3.54 eV. The lower dissociation energy can be attributed to the electron transfer from the Cp ligand to the Pt1/NCNS, thus weakening the interactions between Co and Cp, which facilitates the dissociation process (Supplementary Fig. 19 and Supplementary Table 3). Considering it is a gas phase reaction, the Co(Cp) likely diffuses and deposits on the unoccupied pyrrolic N4 sites through chemisorption. Such a strong chemical bonding of Co with pyrrolic N4 sites will form a stable Co1 structure after the O2 pulse to remove the Cp ligand. It is worth noting that the introduction of O2 may also remove the attached Cp ligand on the Pt1 atom and recover the structure of Pt1/NCNS as shown in the Pt L3 XANES and EXAFS results (Fig. 2g, h). As a result, when the Co ALD is performed on Pt1/NCNS, Co single atoms will form and Pt1 atoms will remain atomic dispersion (Fig. 5b). The principle revealed by the theoretical calculation results indicates that this synthesis strategy could be universal for the rational design of SACs (Supplementary Fig. 20).

Fig. 5. Illustration of theoretical understanding of the Co ALD process.

a Theoretical reaction coordinate for Co(Cp)2 deposition on pristine NCNS and Pt1/NCNS. The Gibbs free energies were calculated at T = 523 K and P = 1 atm. b Illustration of Co ALD process on Pt1/NCNS. The white, brown, blue, orange, and silver spheres represent H, C, N, Co, and Pt, respectively.

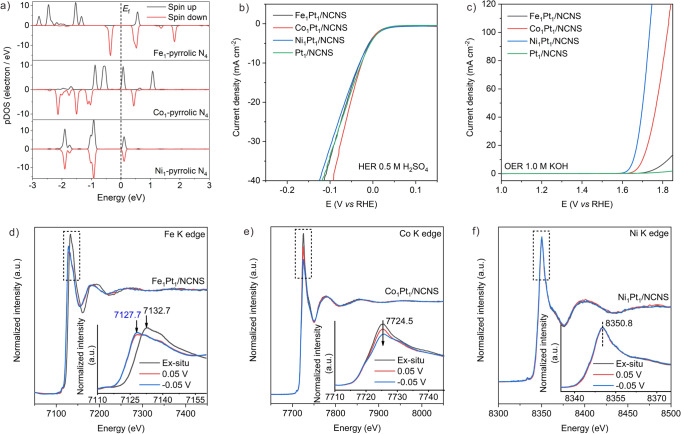

Theoretical simulation and electrocatalytic performance of M1Pt1/NCNS

The capability of application for the achieved M1Pt1/NCNS catalysts was further evaluated in electrochemical reactions. Prior to the experiment, we first studied the projected density of state (pDOS) of various M1-pyrrolic N4 sites. As shown in Fig. 6a, the Co1-pyrrolic N4 and Fe1-pyrrolic N4 show higher DOS near the Fermi level than that of Ni1-pyrrolic N4. As is known, the high electron densities near the Fermi level could facilitate the adsorption of the proton (H+)41–43. Further calculated hydrogen adsorption free energy on Co1-pyrrolic N4 catalyst is closer to zero than that on Fe1-pyrrolic N4, indicating its relatively higher catalytic performance in HER (Supplementary Fig. 21). The Ni1-pyrrolic N4 shows the weakest H adsorption ability, indicating its unsatisfactory HER activity. This theoretical prediction is confirmed by the experiment, in which the Co1Pt1/NCNS showed higher activity than Fe1Pt1/NCNS and Ni1Pt1/NCNS (Fig. 6b). The higher catalytic activity of Co1Pt1/NCNS than the Pt1/NCNS could be attributed to the contributions of Co1 atoms in HER (Supplementary Figs. 22 and 23)44–46. The Co1Pt1/NCNS also exhibits good stability without showing any obvious activity decrease after 8,000 cycles durability test (Supplementary Fig. 24). Although the Ni1-pyrrolic N4 site exhibits low catalytic activity in HER, the high d-band center near the Fermi level on the Ni1 atom (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Table 4) shows the promising application in OER47. In the experiment, the Ni1Pt1/NCNS shows the best catalytic performance among various SACs in OER (Fig. 6c), which confirms the theoretical predication (Supplementary Figs. 25 and 26). The NCNS shows no catalytic activity in OER, indicating the carbon corrosion is not obvious (Supplementary Fig. 27).

Fig. 6. Theoretical and experimental electrocatalytic analysis on M1Pt1/NCNS (M=Co, Fe, and Ni).

a Projected density of state (pDOS) on the M1 3d orbitals with the Fermi level set at zero. HER (b) and OER (c) LSV curves of M1Pt1/NCNS and Pt1/NCNS with IR correction. d–f Operando XANES study on M1Pt1/NCNS catalysts in HER working conditions under different potentials at Fe, Co, and Ni K edges, respectively. Inserts: the enlarged area of XANES region in the dash square.

The non-noble SACs are reported to show promising HER performance but the nature of active sites under HER has not been systematically investigated yet. Therefore, in order to better understand the nature of single-atom sites under reaction, operando XAS experiments were conducted on M1Pt1/NCNS under HER at Fe, Co, and Ni K edges, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 28). As shown in Fig. 6d, a distinct energy chemical shift in the XANES white-line (WL) region can be observed on Fe1Pt1/NCNS at Fe K edge from 7132.7 to 7127.7 eV when the overpotential is applied on 0.05 V. This operando XANES results indicate the reduced oxidation state of Fe from +3 to +2. This Fe3+(d5)/Fe2+(d6) redox transition is probably from the desorption of covered O species or impressed voltage, which would lead to a distorted Fe2+-N4 structure40,48. As shown in Fig. 6e, an obvious WL intensity decrease can be found on the Co1Pt1/NCNS at Co K edge with the increasing overpotentials. Unlike the results of Fe (Supplementary Fig. 29a), the E0 on the Co K edge keeps constant (Supplementary Fig. 29b). This decreased WL intensity indicates the filling of p electrons on Co, which could play an important role in the HER. The constant E0 is likely from the charge redistribution from the hybridization among atomic orbitals in Co, which results in the negligible net effect on E0. In sharp contrast with the operando XANES results on Fe1 and Co1 atoms, neither the E0 nor the WL intensity on Ni K edge of Ni1 atoms showed obvious changes (Fig. 6f and Supplementary Fig. 29c), indicating the Ni1-pyrrolic N4 sites may be intact under HER. We also measured the operando XANES on the Fe, Co, and Ni -NPs/NCNS under HER for comparison, where no changes can be found on all the spectra (Supplementary Fig. 30). These apparently insensitive responses under electrochemical reactions might account for their poor activity in HER (Supplementary Fig. 31).

For the first time, the synthesis of M1-pyrrolic N4 type SACs has been successfully achieved using heterogeneously supported Pt1 atoms as catalysts. This general M1-pyrrolic N4 framework is confirmed by XANES simulation and EXAFS analysis. DFT calculations show that the Pt1 atoms act as the catalyst to modulate the adsorption behavior and promote the dissociation of Co(Cp)2 in Co ALD, which leads to the chemical binding of CoCp on the pyrrolic N4 site and formation of Co single atoms. More importantly, this synthesis strategy can be extended to achieve Fe and Ni SACs. These SACs are evaluated under HER and the nature of single-atom sites are further unveiled by the operando XAS studies. In OER, the Ni1Pt1/NCNS catalyst show much better catalytic activity than the Fe and Co SACs counterparts, which is in excellent agreement with DFT prediction. These new findings extend the application fields of SACs to catalytic fabrication methodology, which is promising for the rational design of advanced SACs. The prominent covalent metal-support interaction bonding of M1 atom (M=Fe, Co, Ni) with the local coordinated N-atoms provides a unique opportunity to further tune the catalytic properties through substrate design49,50.

Methods

Synthesis of g-C3N4

Twelve grams of urea was put into an alumina crucible with a cover and then heated to 580 °C at a rate of 3 °C/min in a muffle furnace and maintained at this temperature for 4 h. After cooling down to room temperature, ~600 mg of bulk g-C3N4 was obtained.

Synthesis of N-doped carbon nanosheet

The synthesis method for the N-doped carbon nanosheets is based on a previous report34. Typically, 500 mg g-C3N4 was mixed with 2.16 g glucose and dispersed in 40 mL of deionized water under sonication for 5 h. After that, the suspension was transferred to a Teflon autoclave and heated at 140 °C for 11 h in an oven. The product was collected by centrifugation and washed with water and ethanol several times, then dried under vacuum at 60 °C overnight. After that, the dried powder was heated up to 900 °C in Ar at a rate of 5 °C/min and maintained at this temperature for 1 h to achieve the N-doped carbon nanosheet (NCNS).

Synthesis of Pt1/NCNS

Pt was deposited on the as-prepared NCNS by ALD (Savannah 100, Cambridge Nanotechnology Inc., USA) using trimethyl(methylcyclopentadienyl)-platinum (IV) (MeCpPtMe3) and O2 as precursors. High-purity N2 (99.9995%) was used as both a purging gas and carrier gas. The deposition temperature was kept at 150 °C, while the container for MeCpPtMe3 was heated to 65 °C to provide a steady flux of Pt to the reactor. The manifold was kept at 115 °C to avoid any condensation5. The timing sequence of one cycle Pt ALD was 15s and 30s for MeCpPtMe3 exposure and N2 purge respectively. Subsequently, the ALD chamber was heated up to 250 °C, with 30s O2 exposure and 30s N2 purge to remove the ligand.

Synthesis of M1Pt1/NCNS (M=Fe, Co, and Ni)

The M ALD is conducted on the as-prepared Pt1/NCNS. The precursor used for Co, Fe and Ni are Ferrocene (Fe(Cp)2), Cobaltocene (Co(Cp)2) and Nickelocene (Ni(Cp)2). High-purity N2 (99.9995%) was used as both a purging gas and carrier gas. The deposition temperature was kept at 250 °C, while the container for M(Cp)2 was heated to 90 °C to provide a steady flux of precursor to the reactor. The manifold was kept at 140 °C to avoid any condensation. The timing sequence of one cycle M ALD was 15s and 30s for M(Cp)2 exposure and N2 purge respectively. Subsequently, the ALD chamber was heated up to 300 °C, with 30s O2 exposure and 30s N2 purge to remove the ligand.

Instrumentation

TEM samples were prepared by drop-casting an ultrasonicated solution of dilute high-performance liquid chromatography grade methanol solution with the sample of interest onto a lacey carbon grid. The TEM characterization was carried out on a FEI Titan Cubed 80–300 kV microscope equipped with spherical aberration correctors (for probe and image forming lenses) at 200 kV. Atomic-resolution high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) images were taken using a double spherical aberration-corrected FEI Themis microscope operated at 300 kV. The corresponding inner and outer collection semi-angles for HAADF imaging were 48–200 mrad. Dual EELS spectrum imaging was performed at a collection semi-angle of 28.7 mrad with a dispersion of 0.5 eV/channel. The metal loadings were analyzed using an inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES) with samples dissolved in hot fresh aqua regia overnight and filtered.

Electrochemical measurements

The electrochemical measurements were performed using a glassy carbon rotating-disk electrode (Pine Instruments) as the working electrode with carbon paper and a standard hydrogen electrode as the counter and reference electrodes, respectively. Ink for the electrochemical measurement was prepared by adding 2 mg of the catalyst into 1 mL ethanol, and Nafion (5% solution, Sigma-Aldrich, 20 μL), followed by sonication for 10 min. A working electrode was prepared by loading the ink (10 μL) on the glassy carbon electrode. The HER test was carried out in 0.5 M H2SO4 with a scan rate of 0.01 V s−1. The durability test was carried out in 0.5 M H2SO4 between −0.1 and 0.4 V at a scan rate of 0.1 V s−1. The OER LSV polarization curves were measured in a O2-saturated electrolyte at a sweep rate of 5 mV s−1. The durability test was carried out on a constant current density of 10 mA/cm2. The measured potential against the reference electrode was converted to a reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE).

XAS measurements

XAS measurements were conducted on the 061D superconducting wiggler at the hard X-ray microanalysis (HXMA) beamline at the Canadian Light Source (CLS) and beamline 20-ID-C at the CLS@APS of the Advanced Photon Source (APS), Argonne National Laboratory (ANL).

At HXMA beamline, each spectrum was collected using fluorescence yield mode with a Canberra 32 element Ge detector. The beamline initial energy calibration for the different edges was made by using the corresponding metallic foils from Exafs Materials, and the same metallic foil was further set between two FMB Oxford ion chamber detectors downstream to the sample, making in-step energy calibration available for each individual XAFS scan.

At 20-ID-C beamline, the XAS measurements were conducted at A Si (111) fixed-exit, double-crystal monochromator was used. Harmonic rejection was facilitated by detuning the beam intensity 15% at ∼1000 eV above the edge of interest. The measurements were performed in fluorescence mode using a four-element Vortex Si Drift detector. Details on the beamline optics and instruments can be found elsewhere51.

Operando XAFS measurements were performed with catalyst-coated carbon paper using a custom-built cell. The carbon paper was pretreated with concentrated nitric acid at 80 °C overnight to ensure thorough electrolyte wetting. The catalyst ink was prepared with the same method as for the electrochemical measurements. The catalyst ink was dropped onto the carbon paper, and the backside of the carbon paper was taped with the Kapton film as the working electrode to ensure the entirety of the electrocatalyst had access to the H2SO4 electrolyte. Carbon paper and Ag/AgCl were used as the counter and reference electrodes. To collect the XAFS spectra during the HER process, the cathodic voltages were held at constant potentials during the operando experiment from 0.05 to −0.05 V (vs RHE), respectively.

XANES modeling

To further understand the nature of experimental resolved XANES features and address them to the structural and chemical nature of M (Fe, Co, and Ni) site occupancy and their corresponding local structural environment, DFT guided XANES theoretical modeling was carried out by using code FDMNES, following standard procedure52. For instance, a Co centered cluster was developed based on the structure model predicated by DFT optimized structures. The radius of the cluster is around 6 Å, corresponding roughly to the detection limit of the XAFS data.

EXAFS data analysis

The data reduction was using codes Athena53. The followed EXAFS R space curve fitting was performed using WINXAS version 2.3, following the procedure reported reference54. In brief, the first inflection point of the XANES edge was defined as the experimental E0, the post-absorption edge background was estimated and removed by cubic spline fits. Based on the local structural environment predicted by DFT theoretical modeling, the scattering amplitudes and phases were calculated using FEFF7.02 and further used for R space curve fitting55. The k rages for FT-EXAFS for Pt L3, Fe, Co, and Ni K edges are 3.15–11.57, 2.50–11.16, 2.37–10.90, and 2.33 to 10.48 Å−1, respectively.

Theoretical and computational methods

First-principles DFT calculations were performed by using the spin-polarized Kohn–Sham formalism with the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) of Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE)56, as implemented in the Vienna ab initio Simulation Package (VASP 5.4.4)57. The valence electronic states of all atoms were expanded in plane-wave basis sets with a cutoff energy of 400 eV, and gamma points were used for Brillouin zone integration. All atoms were allowed to relax until the forces fell below 0.02 eV Å−1. The energy convergence criterion was set to 10−5 eV. The zero-point vibrational energy (ZPE) and entropy corrections were performed by vibrational frequency analysis. We applied a graphene supercell with the surface periodicity of 8 × 8 including 128 atoms as a basis to construct the M-pyrrolic N4 moieties. A vacuum region of 15 Å in the normal direction of the graphene plane was created to ensure negligible interaction between mirror images of the supercells.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), Ballard Power Systems, Canada Research Chair (CRC) Program, Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI), the University of Western Ontario, and the 111 Project of China (D17003). Junjie Li was supported by the China Scholarship Council (CSC). Jun Li and C.-Q.X. acknowledge financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22033005 and 22038002). This work was partially sponsored by the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Catalysis (No. 2020B121201002). Computational resources are supported by the Center for Computational Science and Engineering (SUSTech). This STEM work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21802065) and the Pico Center at SUSTech CRF that receives support from the Presidential fund and Development and Reform Commission of Shenzhen Municipality. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory and was supported by the U.S. DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357, and the Canadian Light Source and its funding partners. The authors also would like to thank Dr. Timothy Fister for the use of the electrochemical workstation during the operando experiments at APS.

Author contributions

Junjie Li and X.S. designed the project. Junjie Li performed the catalyst preparation, catalytic tests, XAS experiment, and wrote the manuscript; Y.J., C.X., and J. Li performed the DFT calculations. Q.W., D.W., and M.G. conducted the HAADF-STEM images acquisition and image analyses; N.C. carried out the XANES and EXAFS data analysis. M.N.B., K.A., K.D., D.M.M., Z.F., and W.L. assisted to run the XAS experiment; L.Z., R.L., and T.-K.S. gave constructive suggestions; X.S. supervised the project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Junjie Li, Ya-fei Jiang, Qi Wang.

Contributor Information

Ning Chen, Email: ning.chen@lightsource.ca.

Meng Gu, Email: gum@sustech.edu.cn.

Jun Li, Email: junli@tsinghua.edu.cn.

Xueliang Sun, Email: xsun9@uwo.ca.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-27143-5.

References

- 1.Qiao B, et al. Single-atom catalysis of CO oxidation using Pt1/FeOx. Nat. Chem. 2011;3:634–641. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao LN, et al. Atomically dispersed iron hydroxide anchored on Pt for preferential oxidation of CO in H2. Nature. 2019;565:631–635. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0869-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yan H, et al. Single-Atom Pd1/graphene catalyst achieved by atomic layer deposition: remarkable performance in selective hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:10484–10487. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan H, et al. Bottom-up precise synthesis of stable platinum dimers on graphene. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1070. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01259-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li J, et al. Highly active and stable metal single-atom catalysts achieved by strong electronic metal–support interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:14515–14519. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b06482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Q, et al. Ultrahigh-loading of Ir single atoms on NiO matrix to dramatically enhance oxygen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:7425–7433. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b12642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao D, et al. Atomic site electrocatalysts for water splitting, oxygen reduction and selective oxidation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020;49:2215–2264. doi: 10.1039/c9cs00869a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan LL, et al. Atomically isolated nickel species anchored on graphitized carbon for efficient hydrogen evolution electrocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10667. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng N, Zhang L, Doyle-Davis K, Sun X. Single-atom catalysts: from design to application. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2019;2:539–573. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang XF, et al. Single-atom catalysts: a new frontier in heterogeneous catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013;46:1740–1748. doi: 10.1021/ar300361m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhuo H-Y, et al. Theoretical understandings of graphene-based metal single-atom catalysts: stability and catalytic performance. Chem. Rev. 2020;120:12315–12341. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaiser, S. K., Chen, Z., Faust Akl, D., Mitchell, S. & Pérez-Ramírez, J. Single-atom catalysts across the periodic table. Chem. Rev. 120, 11703–11809 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Ji S, et al. Chemical synthesis of single atomic site catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2020;120:11900–11955. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang R, et al. Single-atom catalysts based on the metal–oxide interaction. Chem. Rev. 2020;120:11986–12043. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du Z, et al. Cobalt in nitrogen-doped graphene as single-atom catalyst for high-sulfur content lithium–sulfur batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:3977–3985. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b12973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang A, Li J, Zhang T. Heterogeneous single-atom catalysis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2018;2:65–81. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee B-H, et al. Reversible and cooperative photoactivation of single-atom Cu/TiO2 photocatalysts. Nat. Mater. 2019;18:620–626. doi: 10.1038/s41563-019-0344-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou M, et al. Single-atom Ni-N4 provides a robust cellular NO sensor. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3188. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17018-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duchesne PN, et al. Golden single-atomic-site platinum electrocatalysts. Nat. Mater. 2018;17:1033–1039. doi: 10.1038/s41563-018-0167-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vilé G, et al. A stable single-site palladium catalyst for hydrogenations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:11265–11269. doi: 10.1002/anie.201505073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kistler JD, et al. A single‐site platinum CO oxidation catalyst in zeolite KLTL: microscopic and spectroscopic determination of the locations of the platinum atoms. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:8904–8907. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, et al. Discovering partially charged single-atom Pt for enhanced anti-markovnikov alkene hydrosilylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:7407–7410. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b03121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y, et al. A general strategy for fabricating isolated single metal atomic site catalysts in Y zeolite. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:9305–9311. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b02936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han A, et al. Recent advances for MOF‐derived carbon‐supported single‐atom catalysts. Small Methods. 2019;3:1800471. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones J, et al. Thermally stable single-atom platinum-on-ceria catalysts via atom trapping. Science. 2016;353:150–154. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lang R, et al. Non defect-stabilized thermally stable single-atom catalyst. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:234. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08136-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yao Y, et al. High temperature shockwave stabilized single atoms. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019;14:851–857. doi: 10.1038/s41565-019-0518-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X, et al. Supported single Fe atoms prepared via atomic layer deposition for catalytic reactions. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020;3:2867–2874. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cao Y, et al. Atomic‐level insight into optimizing the hydrogen evolution pathway over a Co1‐N4 single‐site photocatalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:12191–12196. doi: 10.1002/anie.201706467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karasulu B, Vervuurt RH, Kessels WM, Bol AA. Continuous and ultrathin platinum films on graphene using atomic layer deposition: a combined computational and experimental study. Nanoscale. 2016;8:19829–19845. doi: 10.1039/c6nr07483a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu J, Elam JW, Stair PC. Atomic layer deposition-sequential self-limiting surface reactions for advanced catalyst “bottom-up” synthesis. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2016;71:410–472. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang H, Wang C, Yan H, Yi H, Lu J. Precisely-controlled synthesis of Au@ Pd core–shell bimetallic catalyst via atomic layer deposition for selective oxidation of benzyl alcohol. J. Catal. 2015;324:59–68. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martensson P, Carlsson J-O. Atomic layer epitaxy of copper-Growth and selectivity in the Cu (II)-2, 2, 6, 6-tetramethyl-3, 5-heptanedionate/H2 process. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1998;145:2926–2931. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu H, et al. Nitrogen‐doped porous carbon nanosheets templated from g‐C3N4 as metal‐free electrocatalysts for efficient oxygen reduction reaction. Adv. Mater. 2016;28:5080–5086. doi: 10.1002/adma.201600398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li L, et al. Tailoring selectivity of electrochemical hydrogen peroxide generation by tunable pyrrolic‐nitrogen‐carbon. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020;10:2000789. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li J, et al. Unveiling the nature of Pt single-atom catalyst during electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution and oxygen reduction reactions. Small. 2021;17:2007245. doi: 10.1002/smll.202007245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi J, Dowben PA. Cobaltocene adsorption and dissociation on Cu (1 1 1) Surf. Sci. 2006;600:2997–3002. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yan H, et al. Atomic engineering of high-density isolated Co atoms on graphene with proximal-atom controlled reaction selectivity. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3197. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05754-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zitolo A, et al. Identification of catalytic sites in cobalt-nitrogen-carbon materials for the oxygen reduction reaction. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:957. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01100-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jia Q, et al. Experimental observation of redox-induced Fe–N switching behavior as a determinant role for oxygen reduction activity. ACS Nano. 2015;9:12496–12505. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b05984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang L, et al. Graphene defects trap atomic Ni species for hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions. Chem. 2018;4:285–297. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen W, et al. Rational design of single molybdenum atoms anchored on N‐doped carbon for effective hydrogen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:16086–16090. doi: 10.1002/anie.201710599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ye S, et al. Highly stable single Pt atomic sites anchored on aniline-stacked graphene for hydrogen evolution reaction. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019;12:1000–1007. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang LZ, et al. Charge polarization from atomic metals on adjacent graphitic layers for enhancing the hydrogen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:9404–9408. doi: 10.1002/anie.201902107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang LZ, et al. Coordination of atomic Co-Pt coupling species at carbon defects as active sites for oxygen reduction reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:10757–10763. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b04647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhuang L, et al. Defect-Induced Pt–Co–Se coordinated sites with highly asymmetrical electronic distribution for boosting oxygen-involving electrocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 2019;31:1805581. doi: 10.1002/adma.201805581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Montemore MM, van Spronsen MA, Madix RJ, Friend CM. O2 activation by metal surfaces: implications for bonding and reactivity on heterogeneous catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2017;118:2816–2862. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li J, et al. Structural and mechanistic basis for the high activity of Fe–N–C catalysts toward oxygen reduction. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016;9:2418–2432. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qiao B, et al. Ultrastable single-atom gold catalysts with strong covalent metal-support interaction (CMSI) Nano Res. 2015;8:2913–2924. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu J-C, Tang Y, Wang Y-G, Zhang T, Li J. Theoretical understanding of the stability of single-atom catalysts. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2018;5:638–641. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heald S, Cross J, Brewe D, Gordon R. The PNC/XOR X-ray microprobe station at APS sector 20. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. 2007;582:215–217. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Joly Y. X-ray absorption near-edge structure calculations beyond the muffin-tin approximation. Phys. Rev. B. 2001;63:125120. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ravel B, Newville M. ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2005;12:537–541. doi: 10.1107/S0909049505012719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ressler, T. WinXAS: A new software package not only for the analysis of energy-dispersive XAS data. J. Phys. IV7, C2-269-C262-C2-26270 (1997).

- 55.Rehr JJ, Albers RC. Theoretical approaches to x-ray absorption fine structure. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2000;72:621. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996;77:3865. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kresse G, Furthmüller J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. 1996;54:11169. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.54.11169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.