Abstract

Vav proteins are guanine nucleotide exchange factors for Rho family GTPases which activate pathways leading to actin cytoskeletal rearrangements and transcriptional alterations. Vav proteins contain several protein binding domains which can link cell surface receptors to downstream signaling proteins. Vav1 is expressed exclusively in hematopoietic cells and tyrosine phosphorylated in response to activation of multiple cell surface receptors. However, it is not known whether the recently identified isoforms Vav2 and Vav3, which are broadly expressed, can couple with similar classes of receptors, nor is it known whether all Vav isoforms possess identical functional activities. We expressed Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3 at equivalent levels to directly compare the responses of the Vav proteins to receptor activation. Although each Vav isoform was tyrosine phosphorylated upon activation of representative receptor tyrosine kinases, integrin, and lymphocyte antigen receptors, we found unique aspects of Vav protein coupling in each receptor pathway. Each Vav protein coprecipitated with activated epidermal growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptors, and multiple phosphorylated tyrosine residues on the PDGF receptor were able to mediate Vav2 tyrosine phosphorylation. Integrin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav proteins was not detected in nonhematopoietic cells unless the protein tyrosine kinase Syk was also expressed, suggesting that integrin activation of Vav proteins may be restricted to cell types that express particular tyrosine kinases. In addition, we found that Vav1, but not Vav2 or Vav3, can efficiently cooperate with T-cell receptor signaling to enhance NFAT-dependent transcription, while Vav1 and Vav3, but not Vav2, can enhance NFκB-dependent transcription. Thus, although each Vav isoform can respond to similar cell surface receptors, there are isoform-specific differences in their activation of downstream signaling pathways.

Ligand engagement of receptors at the cell surface induces the assembly of intracellular protein complexes that transduce signals to the cytoplasm and nucleus to activate many cellular responses. A key class of signaling molecules that mediate receptor-induced rearrangements of the actin cytoskeleton, activation of kinase cascades, and changes in gene transcription is the Rho family of GTPases (46). Although much recent work has focused on the pathways downstream of Rho GTPases which lead to cytoskeletal changes, little is known about how receptor activation at the cell surface leads to the activation of Rho GTPases.

Vav proteins are Rho family guanine nucleotide exchange factors that are ideally suited to couple receptors to Rho GTPases because they contain multiple protein domains that can bind to receptors or receptor-associated signaling proteins (3, 35). In addition, the best-characterized Vav protein, Vav1, is activated by two common signals generated by multiple classes of plasma membrane receptors: tyrosine phosphorylation and the phosphatidylinositol (PI) 3′-kinase product, PI-3,4,5-P3 (3, 16). Stimulation of diverse cell surface receptors including immune response receptors, integrins, and growth factor receptors leads to tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 (3, 6, 14, 31, 55). Thus, Vav proteins may function to transduce signals from diverse receptors to Rho GTPases.

Vav1 was first identified by the isolation of a truncated, constitutively active form of this protein (lacking 67 amino acids at its amino terminus) that induced oncogenic transformation of NIH 3T3 cells (23). However, the endogenous Vav1 protein is expressed exclusively in hematopoietic cells (2, 22). Vav1 plays an important role in lymphocyte development and antigen receptor-mediated signal transduction in mice. T cells lacking Vav1 are impaired in antigen-induced cell proliferation, activation of NFAT and NFκB, interleukin-2 (IL-2) production, and clustering of actin with the T-cell receptor (TCR) into patches and caps (7, 12, 13, 20, 41, 54). Though Vav1 has also been implicated in actin cytoskeletal rearrangements induced by integrins (31), it has not been established whether Vav1 is essential for regulation of these pathways in hematopoietic cells or whether other Vav family members regulate receptor-induced cytoskeletal changes in nonhematopoietic cells.

Recently an additional Vav family member, Vav2, has been identified which is ubiquitously expressed in embryos and adult tissues (18, 37). In this report, we describe a third Vav family member, Vav3, isolated from a mouse cDNA library. During the course of this study, the human homologue of vav3 was also reported (32). vav3 mRNA is detected in a wide spectrum of tissues and cell lines (32; W. Swat, K. Fujikawa, and F. W. Alt, unpublished data). Like Vav1, Vav2 also becomes oncogenic upon deletion of its amino terminus; however, in one report the morphology of vav2-transformed cells was distinct from that of vav1-transformed cells, suggesting that there may be differences in downstream effectors of these two family members (1, 37). In contrast, the expression of truncated versions of Vav3 does not cause oncogenic transformation but does induce the formation of actin-based structures such as lamellipodia and stress fibers (32). As with Vav1, tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav2 or Vav3 enhances its guanine nucleotide exchange factor activity in vitro (32, 37).

Although the plasma membrane receptors that couple with Vav1 have been well characterized, relatively little is known about the events leading to activation of Vav2 or Vav3 (which are expressed in both nonhematopoietic cells and hematopoietic cells). In addition, it is unknown whether Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3 can couple with the same cell surface receptors or whether any of these family members possess unique functional activities. Because most cells are likely to express more than one Vav family member, it is possible that each Vav protein may specifically couple with different receptor classes, or that Vav proteins are activated by the same classes of receptors but induce different cellular responses due to specific interactions with downstream effectors.

In this report, we directly compare the abilities of Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3 to couple with cell surface receptor signaling pathways. We demonstrate that transiently expressed Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3, as well as endogenous Vav2, are inducibly phosphorylated on tyrosine in response to platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), integrin, T-cell, and B-cell receptor activation. Interestingly, however, our studies revealed unique aspects of the way Vav proteins couple with each receptor pathway, indicating that the activation of Vav proteins is dependent on different signaling proteins in distinct cell types. In addition, we found differences in the activation of downstream signaling pathways by Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3 that provide a potential explanation for the specific defects in vav1−/− T cells and further evidence for isoform-specific functions of Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning of murine vav3 cDNA.

To obtain a full-length murine vav3 cDNA, we used a nested reverse transcription (RT)-PCR strategy with primers based on a vav-related human cDNA sequence fragment obtained from S. Orkin (The Children's Hospital, Boston, Mass.). A 438-bp fragment (probe K) corresponding to nucleotides 1140 to 1578 of murine vav3 cDNA was amplified and used to screen a murine brain cDNA library (λZAP2; Stratagene); this yielded several vav3 cDNA clones extending toward the 5′ end. Two of these clones contained a consensus Kozak ATG (25); one additionally contained approximately 400 bp of 5′ untranslated region. To obtain vav3 cDNA sequences 3′ of probe K, two murine expressed sequence tag clones (AA518328 and AA517102) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC); each of these was found to contain the 3′ end of murine vav3 cDNA, including the 3′ untranslated region and the poly(A) tail. Subsequently, the gaps between probe K and the 3′ expressed sequence tag sequences were closed by RT-PCR using murine spleen or thymus mRNA. While this work was in progress, complete murine (AF067816) and human (AF118887) vav3 cDNA sequences were deposited in GenBank.

Antibodies.

Antibodies for immunoprecipitation of hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged proteins were the monoclonal antibody 12CA5 (47) and the polyclonal HA probe (Santa Cruz). PDGFβ receptor (PDGFβR) was immunoprecipitated using a polyclonal antibody to the kinase insert region (PharMingen), and endogenous Vav1 was immunoprecipitated using a rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz). The monoclonal antibodies HA-11 (Berkeley Antibody Company) and 4G10 (kindly provided by T. Roberts, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Mass.) were used on immunoblots to detect HA-tagged proteins and phosphotyrosine, respectively. A rabbit polyclonal antibody which recognizes Vav2 was developed using a synthetic peptide corresponding to residues 653 to 665 of human Vav2 as antigen (Covance, Denver, Pa.). Stimulatory antibodies for T- and B-cell activation were mouse anti-human CD3ε (PharMingen) and goat anti-human or goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG)-IgM (heavy plus light chain [H+L]) (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories).

Cell lines, plasmids, and transfections.

The HepG2 cell lines which stably express variants of PDGFβR were described previously (44). The A5 CHO cell line (27) stably expresses αIIbβ3 integrin. We used Jurkat E6 cells (ATCC), which are CD3+ human T-lymphoblastoid cells. Daudi cells (ATCC) are soluble IgM+ human B-lymphoblastoid cells.

The human vav1 cDNA was obtained from A. Altman (La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology, San Diego, Calif.). The human vav2 cDNA was kindly provided by D. Kwiatkowski (Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Mass.). To generate HA-tagged Vav proteins, full-length vav1, vav2, and vav3 cDNAs were amplified by PCR and inserted into plasmid pCF1-HA, derived from plasmid pCG (40). The pEMCV-myc-Syk construct has been described elsewhere (31).

Cos7 and A5 CHO cells were transfected at 50 to 60% confluency with 4 μg of total DNA on 100-mm-diameter tissue culture plates using 8 μl of LT1 reagent (PanVera) per plate. NIH 3T3 cells were transfected using 10 μl Lipofectamine reagent (Gibco-BRL) per plate. Cells were incubated with the DNA-lipid complexes 6 h in 4 ml of RPMI 1640; then 4 ml of complete growth medium was added, and cells were incubated for an additional 16 to 20 h. Cells were then serum starved for 20 to 24 h in 0.1% fetal bovine serum in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Cos7, A5 CHO, and HepG2 cells) or 0.1% calf serum in DMEM (NIH 3T3 cells); 107 Jurkat or Daudi cells were transfected by electroporation (Bio-Rad electroporator, 220 V, 960 μF). The amounts of plasmid DNA used were as follows: for Cos7, A5 CHO, and NIH 3T3 cells, 0.05 to 0.5 μg of pCF1-HA, Vav1-HA, Vav2-HA, and Vav3-HA plus 0.25 μg of pEMCV-Syk; for Jurkat and Daudi cells, 5 to 40 μg of pCF1-HA, Vav1-HA, Vav2-HA, and Vav3-HA plus 10 μg of pNFATx3 or SV40κB-luc.

Growth factor stimulation, adhesion assays, and antigen receptor activation.

For growth factor stimulation of transfected cells, starvation medium was replaced with DMEM without phenol red plus EGF (50 ng/ml; R&D Systems) or PDGF-BB (100 ng/ml; Upstate Biotechnology Incorporated) unless otherwise noted or DMEM without phenol red plus vehicle control (2% bovine serum albumin in 10 mM acetic acid). After stimulation (2 min with EGF or 10 min with PDGF-BB unless otherwise noted), cells were washed once with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then lysed on plates using cold NP-40 lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.6], 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 10% glycerol, 1% NP-40, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 μg each of leupeptin, aprotinin, and pepstatin per ml) for 10 min at 4°C. Plates were then scraped, and the crude lysate was transferred to tubes and cleared by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C.

Adhesion assays were performed essentially as described elsewhere (31). Briefly, serum-starved cells were harvested and held in suspension for 30 min before replating. Cells were plated on fibronectin-coated plates (10 μg/ml) and allowed to adhere 15 to 20 min. Nonadherent cells were removed from matrix-coated plates, and the adherent cells were lysed in 300 μl of cold NP-40 lysis buffer. Suspended cells were held in a small volume of DMEM without phenol red and then lysed in an equal volume of cold 2× NP-40 lysis buffer. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C.

Jurkat T-lymphoid and Daudi B-lymphoid cells were stimulated 16 to 24 h after transfection. Cells were washed once in PBS, resuspended at 108 cells/ml, and then incubated for 5 min at 37°C with or without the addition of stimulatory antibodies: mouse anti-human CD3ε (10 μg/ml) followed by goat anti-mouse IgG-IgM (H+L) (10 μg/ml) for Jurkat T cells, or goat anti-human IgG-IgM (H+L) (10 μg/ml) for Daudi B cells. Stimulations were terminated by the addition of excess cold PBS; cells were then washed once and lysed in 100 μl of cold lymphocyte lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Boehringer Mannheim). Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting.

Protein concentrations of cleared lysates were determined using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Pierce). For immunoprecipitation, 250 to 500 μg of protein in a total volume of 500 μl of NP-40 lysis buffer was incubated with 1 μg of antibody and 30 μl of a 50:50 slurry of protein A-conjugated Sepharose beads (Pharmacia or Bio-Rad) with rotation for 2 to 3 h at 4°C. Immunoprecipitates were washed twice with cold NP-40 lysis buffer, resuspended in 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer, and frozen at −20°C. Samples were boiled 5 min before loading on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels for analysis. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad); the membrane was then blocked in 5% bovine serum albumin in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 and incubated with primary antibody followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Bio-Rad). Signals were visualized by chemiluminescence.

Luciferase assay for NFAT and NFκB activation.

Jurkat T cells were cotransfected by electroporation with either pNFATx3-luciferase (17) or SV40κB-luc (43) reporter construct plus pCF1-HA, Vav1-HA, Vav2-HA, or Vav3-HA. Following electroporation, cells were resuspended in culture medium and incubated for 16 to 18 h at 37°C in a humidified CO2 incubator. For stimulations, cells were diluted to 106 cells/ml and incubated 8 h at 37°C with or without the addition of stimulatory antibodies. Cells were washed once in PBS and lysed in 200 μl of cold lymphocyte lysis buffer; then luciferase was assayed using the Promega luciferase assay system and a luminometer (AutoLumat LB953; EG&G Berthold).

RESULTS

Sequence comparisons between Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3 proteins.

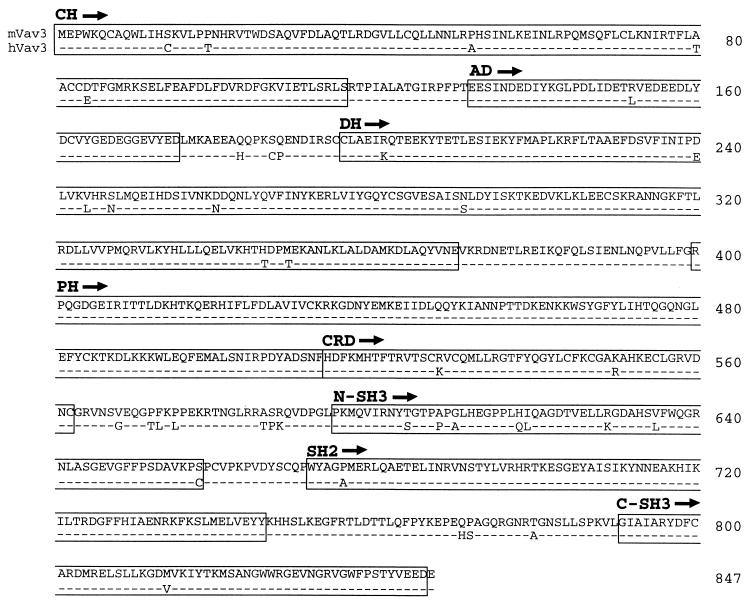

We cloned the murine vav3 cDNA using a RT-PCR strategy combined with standard cDNA library screening (see Materials and Methods). Sequence comparison of the human and mouse Vav3 proteins (Fig. 1) reveals 95% identity over their 847 residues.

FIG. 1.

Sequence alignment of murine and human Vav3 proteins. Residues in human Vav3 (hVav3) identical to those in murine Vav3 (mVav3) are indicated with dashes. The boxes indicate structural domains: calponin homology (CH), acidic domain (AD), Dbl homology (DH), pleckstrin homology (PH), cysteine-rich domain (CRD), Src homology 3 (SH3), Src homology 2 (SH2).

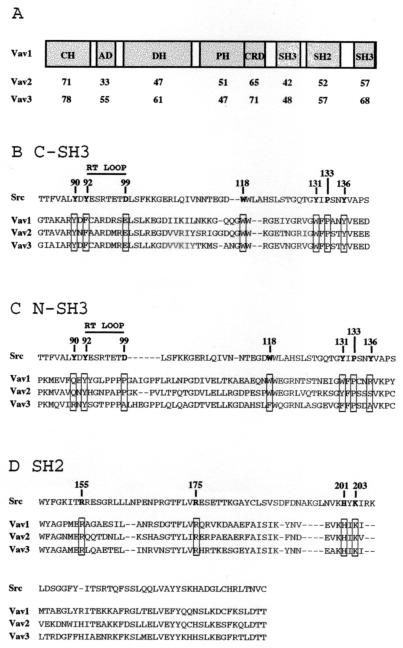

The overall domain structure of Vav3 is analogous to that of Vav1 and Vav2 (Fig. 2A). The carboxy-terminal SH3 (C-SH3) domains of all three Vav proteins are highly homologous and share consensus residues found in the SH3 domains of Src and other proteins. These include the key residues predicted to form the binding site for a core PXXP ligand (Fig. 2B) (11, 53). Thus, all three Vav proteins would be predicted to bind similar PXXP ligands through their C-SH3 domains.

FIG. 2.

(A) Schematic features of Vav proteins and relative homology by domain. Percent identity with human Vav1 within each domain is displayed for human Vav2 and human Vav3. Domain abbreviations are as in Fig. 1. (B) Alignment of the SH3 domain of Src with the C-SH3 domains of Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3. The residues in Src predicted to contact a PXXP ligand are indicated, and the corresponding residues in the Vav proteins are boxed. (C) Alignment of the SH3 domain of Src with the N-SH3 domains of Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3. (D) Alignment of the SH2 domain of Src with the SH2 domains of Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3. The residues in Src predicted to contact the phosphotyrosine in the ligand are indicated, and the corresponding residues in the Vav proteins are boxed.

In contrast, the amino-terminal SH3 (N-SH3) domains of the Vav proteins diverge from standard SH3 domains, notably in the residues predicted to contact a PXXP ligand (Fig. 2C). The Vav N-SH3 domains lack a tyrosine residue corresponding to Y136 of the Src SH3 domain. This tyrosine is predicted to form part of a hydrophobic pocket involved in binding a proline residue in the ligand (11, 53). The analogous residues in the three Vav proteins are strikingly divergent in character: arginine in Vav1, serine in Vav2, and alanine in Vav3. In addition, the N-SH3 domain of Vav3 contains a substitution of phenylalanine for the highly conserved tryptophan corresponding to residue 118 of Src. Although conservative, only a small number of SH3 domains contain this substitution, and no ligand has been identified for any such SH3 domain. In addition, the RT loop (residues between the A and B β strands) of the N-SH3 domain of each Vav protein contains an insertion (six residues for Vav1 and Vav3; four residues for Vav2) but no acidic residue that corresponds to the highly conserved D99 of the Src SH3 domain (Fig. 2C). The extended RT loops of the amino-terminal Vav SH3 domains contain multiple proline residues that may serve as ligands for other SH3 domains. Vav1 contains a PPPP motif that is required for binding to a Grb2 SH3 domain (51). Though Vav2 contains a related sequence in this same position, PPAP, Vav3 lacks the final proline (PPPA in human; PAPG in mouse) and thus does not fit as a consensus SH3-binding ligand.

The SH2 domains of all three Vav proteins are highly homologous; the residues predicted to interact with a phosphotyrosine-containing ligand are identical (10, 48) (Fig. 2D). The residues in the Vav SH2 domains predicted to interact with the +1, +2, and +3 positions of the ligand (corresponding to residues 200, 202, 205, 214, and 215 of the Src SH2 domain 148) are either identical or highly conserved between the three Vav proteins, suggesting that the SH2 domain of each Vav protein may bind ligands with similar sequences.

The linker sequences bordering the SH2 and SH3 domains are not well conserved between the three Vav proteins. Strikingly, Vav2 contains an additional 32 residues between the SH2 and the C-SH3 domains compared to Vav1 (27 residues compared to Vav3). A vav2 cDNA has been isolated that lacks sequences encoding 29 of the residues in this linker region, suggesting that this insert may be generated by alternative splicing (18).

Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3 are tyrosine phosphorylated in response to EGF and PDGF.

Although Vav1 can be tyrosine phosphorylated following stimulation by EGF and PDGF (5, 29), Vav1 is not normally found in cells that express the receptors for these growth factors. Vav2 and Vav3, which are expressed more widely, represent potential physiological targets of these growth factors and may link growth factor receptors to Rho GTPases in nonhematopoietic cells. To address whether these Vav isoforms can be activated by EGF and PDGF, we examined the ability of these growth factors to induce tyrosine phosphorylation of transiently expressed HA-tagged variants of each Vav family member and also examined the phosphorylation of the endogenous Vav2 protein. Together, these approaches allowed us to directly assess the relative extent to which each Vav protein could be phosphorylated in response to activation of each growth factor receptor and to determine whether the endogenous Vav2 protein was also able to couple with these receptors. We were unable to analyze endogenous Vav3 due to lack of a suitable antiserum.

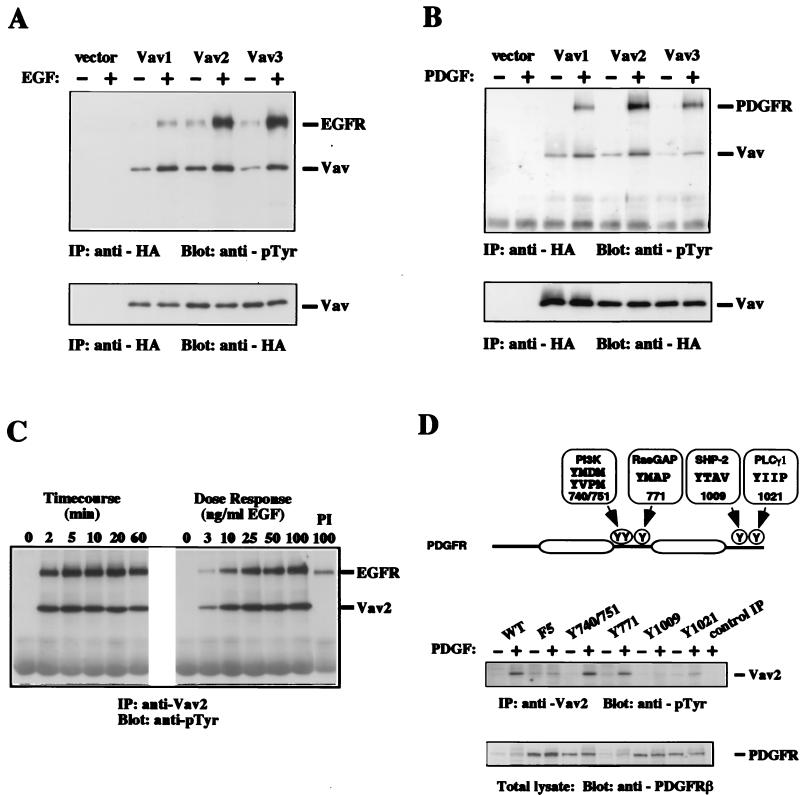

Plasmids encoding HA-tagged variants of Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3 were transiently transfected into Cos7 cells and NIH 3T3 cells. Treatment of serum-starved transfected Cos7 cells with EGF or NIH 3T3 cells with PDGF resulted in an increase in the tyrosine phosphorylation of HA-tagged Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3 (Fig. 3A and B). A tyrosine-phosphorylated band of approximately 170 kDa coprecipitated with each Vav protein in the samples from EGF-stimulated cells (Fig. 3A). This band was confirmed as the EGF receptor (EGFR) by immunoblotting duplicate samples (S. L. Moores and J. S. Brugge, unpublished data). Likewise, the PDGFR coprecipitated with each Vav protein in PDGF-stimulated cells (Fig. 3B). Thus, each Vav protein was inducibly tyrosine phosphorylated in response to stimulation with EGF or PDGF and formed a complex with the activated receptor.

FIG. 3.

EGF- and PDGF-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3. Cos7 (A) or NIH 3T3 (B) cells were transfected with vector only, HA-Vav1, HA-Vav2, or HA-Vav3, serum starved, and then left untreated (−) or treated with growth factor (+). Vav proteins were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-HA antibody from cell lysates, and the level of phosphotyrosine was analyzed by immunoblotting with antiphosphotyrosine (anti-pTyr) antibody (upper panels). The relative amount of tyrosine-phosphorylated EGFR coprecipitated by each Vav protein varied from experiment to experiment. The mobilities of Vav proteins, EGFR, and PDGFR are indicated. Levels of Vav proteins were measured in duplicate anti-HA immunoprecipitations followed by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody (lower panels). These data are representative of four independent experiments. (C) Cos7 cells were serum starved and then treated with 50 ng of EGF per ml for the indicated times (Timecourse) or treated with the indicated amounts of EGF for 2 min (Dose Response). Cells were then lysed, and proteins were immunoprecipitated with antibodies specific for Vav2. The level of phosphotyrosine was determined by immunoblotting with antiphosphotyrosine antibody. PI, preimmune serum. The mobilities of Vav2 and EGFR are indicated. The results are representative of two independent experiments. (D) Schematic diagram of the PDGFβR showing the tyrosine residues involved in this analysis. The tyrosine residue numbers as well as the subsequent three residues (+1, +2, and +3) are shown as the binding sites for PI 3′-kinase, RasGAP, SHP2, and PLCγ1 (24, 44). HepG2 cells expressing PDGFβR variants were serum starved and then left untreated (−) or treated with PDGF (+). Cells were then lysed, and proteins were immunoprecipitated with antibodies specific for Vav2 (or rabbit IgG for the control). The level of phosphotyrosine was determined by immunoblotting with antiphosphotyrosine antibody. Whole-cell extracts were immunoblotted with anti-PDGFβR antibodies to measure the level of each PDGFβR variant expressed. WT, wild type; F5, five tyrosines changed to phenylalanine. Derivative mutants have the following tyrosines added back to the F5 receptor: Y740/751, tyrosines 740 and 751; Y771, tyrosine 771; Y1009, tyrosine 1009; and Y1021, tyrosine 1021. The results shown are from a single representative experiment that was repeated three times with similar results.

To examine the endogenous Vav2 protein, a polyclonal antibody was raised to a Vav2-specific peptide sequence. This antibody, which does not cross-react with Vav1 or Vav3 (Moores and Brugge, unpublished), was used to immunoprecipitate endogenous Vav2 from Cos7 cells following treatment with EGF for the times and doses indicated in Fig. 3C. EGF induced rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav2, which reached a maximal level within the shortest interval tested (2 min). The EGF dose necessary for maximal induction was approximately 25 ng/ml, and the response was not diminished at doses up to 100 ng/ml. PDGF also induced a rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of endogenous Vav2 (see below). While this study was in progress, Pandey and coworkers described EGF- and PDGF-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of endogenous Vav2 (33). In agreement with our data, they also reported coprecipitation of activated EGFR or PDGFR with Vav2.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav2 can be mediated through multiple individual tyrosine residues in the PDGFβR.

Vav proteins and activated receptor tyrosine kinases are likely to interact via the SH2 domain of Vav and phosphorylated tyrosine residues on the receptors (5, 29). To examine which tyrosine phosphorylation sites on the PDGFβR were sufficient to induce phosphorylation of Vav2, we examined the ability of several previously characterized PDGFβR mutants (44) to induce tyrosine phosphorylation of endogenous Vav2 (Fig. 3D). The F5 mutant contains phenylalanine substitutions for tyrosine residues 740, 751, 771, 1009, and 1021 (44). Each derivative mutant contains a single tyrosine residue (and in one case, two tyrosine residues) added back to the F5 receptor (Fig. 3D). Adding back these tyrosine residues recreates the binding sites for PI 3′-kinase (Y740/751), Ras-specific GTPase-activating protein (Ras-GAP) (Y771), SHP2 (Y1009), or phospholipase Cγ1 (PLCγ1) (Y1021) (24, 44).

These PDGFβR mutants were stably expressed in HepG2 cells, which express very little PDGFαR and no endogenous PDGFβR (45). Therefore, stimulation of the transfected cell lines with PDGF leads to activation of the stably expressed exogenous PDGFβR. In HepG2 cells stably expressing wild-type PDGFβR, immunoprecipitated endogenous Vav2 was tyrosine phosphorylated after treatment with PDGF (Fig. 3D). Treatment of the HepG2 cells expressing F5 or Y1009 receptor with PDGF did not cause an increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav2, even though these receptors were expressed at a high level (Fig. 3D). However, PDGF did cause an increase in Vav2 tyrosine phosphorylation in HepG2 cells expressing the Y740/751 or Y771 receptor (Fig. 3D). A small but reproducible PDGF-induced increase in Vav2 tyrosine phosphorylation was also detected in cells expressing the Y1021 receptor (Fig. 3D). Therefore, tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav2 can be mediated through several distinct tyrosine residues on the PDGFβR, suggesting that Vav proteins can bind directly to multiple sites on the receptor or can couple with proteins that bind to multiple sites on the receptor.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav proteins in response to integrin activation requires Syk.

Vav1 becomes tyrosine phosphorylated in response to stimulation of several integrin family receptors in hematopoietic cells (6, 14, 55). In addition, we have reconstituted integrin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 in CHO cells expressing the platelet integrin receptor αIIbβ3 and the tyrosine kinase Syk (31). Vav1 and Syk coexpression causes a strong Rac-dependent enhancement of lamellipodium formation in CHO cells attached to fibrinogen (31), suggesting that Vav1 is able to couple with Rac to enhance the assembly of lamellipodia in response to integrin engagement. These studies raised the possibility that other Vav isoforms may couple integrins to Rac in nonhematopoietic cells.

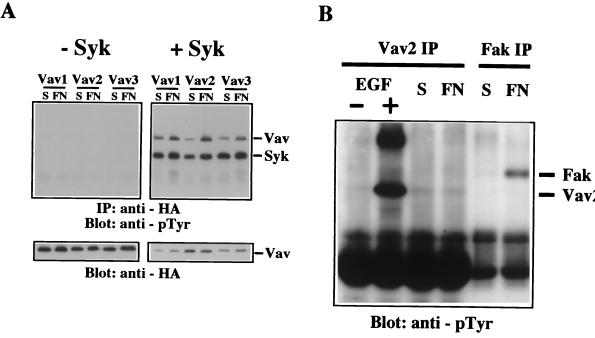

To examine whether Vav2 or Vav3 could be tyrosine phosphorylated in response to integrin activation in this reconstituted CHO cell system, plasmids encoding HA-tagged Vav1, Vav2, or Vav3 were transiently transfected, and cells were either held in suspension or plated on fibronectin prior to lysis and immunoprecipitation of the Vav proteins. We were unable to detect tyrosine phosphorylation of any Vav protein after attachment of cells to fibronectin, although the Vav proteins were expressed at high levels (Fig. 4A, left). These results indicated that integrin fibronectin receptors were unable to couple with tyrosine kinases capable of phosphorylating Vav proteins in CHO cells.

FIG. 4.

Expression of Syk allows integrin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3. (A) A5 CHO cells were transfected with plasmids expressing HA-Vav1, HA-Vav2, or HA-Vav3 alone (left) or in combination with pEMCV-Syk (right). Cells were serum starved and then placed in suspension (S) or plated on fibronectin (FN). Vav proteins were immunoprecipitated (IP) from cell lysates with anti-HA antibody, and the level of phosphotyrosine was analyzed by immunoblotting with antiphosphotyrosine (anti-pTyr) antibody. The mobilities of Vav proteins and Syk are indicated. Levels of Vav proteins in the immunoprecipitates were measured by reprobing the blots with anti-HA antibody. The results are representative of two independent experiments. (B) Cos7 cells were serum starved and then left untreated (−) or treated with EGF (+). Additional Cos7 cells were serum starved and then placed in suspension (S) or plated on fibronectin (FN). Cells were then lysed, and protein immunoprecipitated with antibodies specific for Vav2 (Vav2 IP) or focal adhesion kinase (Fak IP). The level of phosphotyrosine was determined by immunoblotting with antiphosphotyrosine antibody. The mobilities of Vav2 and Fak are indicated. These data are representative of three independent experiments.

Because Syk is required for Vav1 phosphorylation mediated by αIIbβ3 in CHO cells (31), we examined whether Syk expression could also allow Vav2 and Vav3 to couple with fibronectin receptors. Coexpression of Syk with each Vav protein individually caused an inducible increase in tyrosine phosphorylation on Vav when the cells were plated on fibronectin (Fig. 4A, right). A 72-kDa tyrosine-phosphorylated protein coprecipitated with each Vav protein only in cells where Syk was expressed, suggesting that Syk is able to interact with each of the three Vav proteins. These results introduced the possibility that Vav coupling with integrins may be limited to hematopoietic cells where integrins can activate the protein tyrosine kinase Syk.

To further explore this possibility, we examined whether endogenous Vav2 could be phosphorylated following engagement of fibronectin receptors in Cos7 cells where Vav2 was phosphorylated in response to growth factor stimulation (as shown in Fig. 3C). Vav2 was immunoprecipitated from Cos7 cells held in suspension or attached to fibronectin. As in CHO cells, there was no detectable increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav2 following plating of cells on fibronectin (Fig. 4B). In the same samples, there was induction of tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) (Fig. 4B), demonstrating that integrin receptors were efficiently activated (34). EGF treatment of a parallel culture was included as a positive control (Fig. 4B). There was also no detectable increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav2 in Cos7 cells following plating on laminin or collagen (Moores and Brugge, unpublished). These results suggest that integrin receptor activation of Vav proteins may be limited to cells expressing particular tyrosine kinases like Syk that are able to phosphorylate Vav.

Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3 are tyrosine phosphorylated in response to lymphocyte antigen receptor activation.

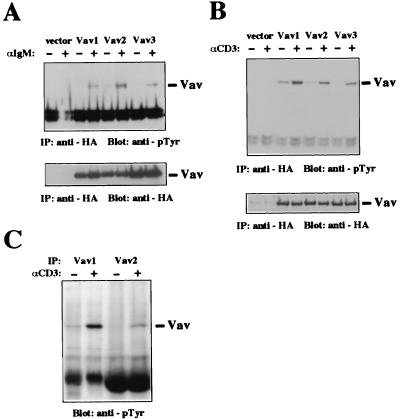

Vav1 becomes phosphorylated on tyrosine in response to both B-cell receptor (BCR) and TCR activation (4, 5, 29); loss of Vav1 in mice causes defects in the development of lymphocytes in vivo and antigen receptor-induced responses in vitro (7, 12, 13, 20, 41, 54). These results suggest a unique function for Vav1 in lymphocytes and raise the questions whether other isoforms of Vav can be activated by BCR and TCR and whether Vav isoforms have distinct functional activities. To address these questions, we examined whether Vav2 and Vav3 can be tyrosine phosphorylated after engagement of these receptors. We used the Jurkat and Daudi immortalized T- and B-cell lines for these studies because their responses to engagement of antigen receptors are well characterized and they can be efficiently transfected. Jurkat and Daudi cells were transiently transfected with plasmids encoding HA-tagged Vav1, Vav2, or Vav3, and tyrosine phosphorylation of individual tagged Vav proteins was examined after cell stimulation with antibodies to the antigen receptor complexes. All three Vav proteins were inducibly phosphorylated on tyrosine in both Jurkat and Daudi cells upon engagement of antigen receptors (Fig. 5A and B). TCR engagement in Jurkat T cells reproducibly induced a slightly higher level of tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 than of Vav2 or Vav3 (Fig. 5B), while the engagement of BCR in Daudi B cells induced similar levels of tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3 (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

TCR- and BCR-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3. Daudi B cells (A) or Jurkat T cells (B) were transfected with vector only, HA-Vav1, HA-Vav2, or HA-Vav3 and then left untreated (−) or treated with stimulatory antibodies (+). Vav proteins were immunoprecipitated (IP) from cell lysates with anti-HA antibody. The level of phosphotyrosine was analyzed by immunoblotting with antiphosphotyrosine (anti-pTyr) antibody (top), and the level of Vav proteins was measured by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody (bottom). The mobilities of Vav proteins are indicated. The data are representative of three independent experiments. The higher level of Vav2 phosphorylation in the stimulated Daudi cells was not reproducible. (C) Jurkat T cells were left untreated (−) or treated with stimulatory antibodies (+), and endogenous Vav proteins were immunoprecipitated with antibodies specific for Vav1 or Vav2. The level of phosphotyrosine was analyzed by immunoblotting with antiphosphotyrosine antibody. The mobilities of Vav proteins are indicated.

We also examined the tyrosine phosphorylation of the endogenous Vav1 and Vav2 proteins in T lymphocytes following TCR activation. Both Vav1 and Vav2 were inducibly tyrosine phosphorylated after TCR stimulation in Jurkat T cells (Fig. 5C). Endogenous Vav3 was also reported to be phosphorylated after TCR stimulation in Jurkat T cells (33). Thus, all three Vav proteins can couple with antigen receptors in T and B lymphocytes.

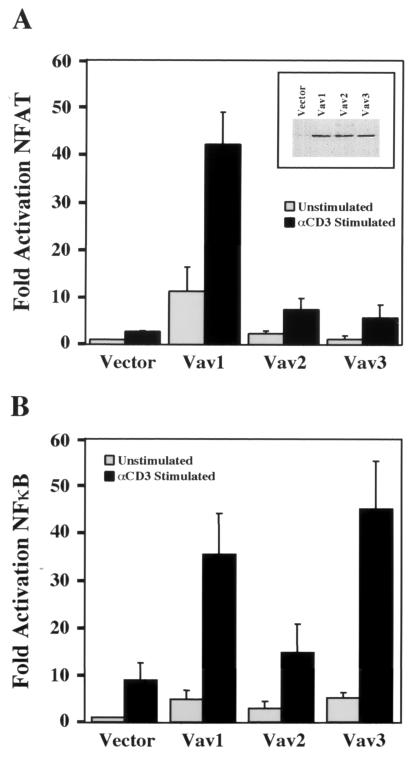

Differential effects of Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3 on activation of NFAT- and NFκB-dependent transcription in antigen receptor-stimulated T cells.

Because all three Vav isoforms were tyrosine phosphorylated in response to TCR engagement, we could not explain the defects in antigen receptor-induced NFAT- and NFκB-dependent transcription and IL-2 production observed in vav1−/− mice (7, 12, 13, 20, 41, 54) by the inability of Vav2 and Vav3 to couple with the TCR complex. We hypothesized that Vav2 and Vav3 might not be able to activate Vav1 downstream effector pathways controlling cytokine gene expression in T cells. To test this hypothesis, we examined the ability of Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3 to synergize with TCR signaling to activate transcription of an NFAT- or NFκB-dependent luciferase reporter gene. Consistent with previously reported results (19, 49, 50), stimulation of Jurkat T cells with anti-CD3 antibodies resulted in activation of both NFAT- and NFκB-dependent transcription, which was strongly potentiated by overexpression of Vav1 in each case (Fig. 6). In contrast, similar levels of expression of Vav2 had little or no effect on NFAT (Fig. 6A) or NFκB (Fig. 6B) activity in response to TCR stimulation. Though expression of Vav3 also failed to potentiate NFAT-dependent transcription (Fig. 6A), it was able to activate NFκB to levels similar to those observed with Vav1 (Fig. 6B). These results suggest functional overlap between Vav1 and Vav3 in the pathway leading to NFκB induction but a specific role for Vav1 in a pathway leading to NFAT activation, which could at least partially account for impaired antigen responses in Vav1-deficient lymphocytes.

FIG. 6.

Potentiation of TCR-induced NFAT- and NFκB-dependent transcriptional activity by overexpression of Vav proteins. Jurkat T cells were cotransfected with an NFAT (A)- or NFκB- (B)-responsive luciferase reporter construct and either vector, HA-Vav1, HA-Vav2, or HA-Vav3. Cells were unstimulated or treated with stimulatory antibodies, as indicated, and lysed; then luciferase activity was measured. The results are shown as fold induction of luciferase activity compared with the activity in unstimulated cells cotransfected with vector and the luciferase reporter construct. Error bars represent standard errors of the means of three (A) or six (B) independent experiments. Inset in (A) shows the level of each Vav protein in cell lysates measured by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody in a single representative experiment for assays in both panel A and panel B.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we demonstrate that the Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3 proteins are each tyrosine phosphorylated in response to activation of receptor tyrosine kinases, lymphocyte antigen receptors, and integrins, suggesting that the known Vav isoforms do not display significant differences in coupling with cell surface receptors. However, our studies revealed differences in specific aspects of signal transduction involving Vav proteins in each receptor system. For example, we were unable to detect integrin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav proteins in nonhematopoietic cell lines unless the protein tyrosine kinase Syk was coexpressed. Because Syk is expressed in all hematopoietic cell types in which Vav1 is known to be activated following engagement of integrins (6, 14, 55), these results suggest Syk may allow integrins to couple with Vav in hematopoietic cells. Thus, while the coupling of Vav proteins to receptor tyrosine kinases occurs in both hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells, integrin coupling with Vav proteins appears to be dependent on the activation of particular protein tyrosine kinases like Syk and therefore is limited to certain cell types where these kinases are expressed.

Src family tyrosine kinases (Lck and Fyn) (15, 30), Syk family tyrosine kinases (Syk and Zap70) (9, 30), and receptor tyrosine kinases (EGFR and PDGFR) (5, 29) have been implicated as mediators of Vav tyrosine phosphorylation. Although it is likely that Vav proteins form a complex with activated receptor tyrosine kinases and can be substrates for them in vitro, it is not clear whether EGFR or PDGFR phosphorylates Vav proteins directly or by activating other protein tyrosine kinases in cells.

Although our studies suggest that integrin coupling to Vav may be limited to cells expressing Syk family kinases, we cannot rule out the possibility that integrin-activated protein tyrosine kinases other than those examined in this report can phosphorylate Vav in nonhematopoietic cells. Because we were unable to detect an increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav in Cos7 or CHO cells attached to fibronectin, it is likely that the protein tyrosine kinases activated by fibronectin receptors in these cells (Src family kinases [21], Abl [28], and Fak [34]) are unable to couple with Vav. Similarly, B. Liu and K. Burridge could not detect integrin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav2 in 293 or NIH 3T3 cells, other nonhematopoietic cell lines (unpublished data). However, Yron et al. reported that in another CHO cell line, adhesion to fibronectin induced the tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 (52). Because this CHO cell line is able to proliferate in suspension and thus is anchorage independent, it is possible that these cells express an activated kinase capable of phosphorylating Vav. Integrins may be able to activate Vav proteins independently of tyrosine phosphorylation, and so the inability to detect integrin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav in CHO, Cos7, 293, and NIH 3T3 cells may not reflect an inability of integrins to activate Vav in these cells.

Syk family tyrosine kinases may also be required for coupling of Vav proteins to other receptor types. Tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 in response to FcεRI activation requires coexpression of Syk in Cos7 cells (42). In T cells lacking the Syk-related tyrosine kinase ZAP-70, no TCR-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 is detected (36). Although the Src family kinases Lck and Fyn have been implicated in Vav phosphorylation in T cells, it is not clear whether they act directly on Vav in these cells or whether they are required for ZAP-70 or Syk activation. Therefore, the specific protein tyrosine kinases that directly phosphorylate Vav proteins in response to activation of cellular receptors are still not known but are likely to be distinct tyrosine kinases depending on the receptor type activated.

There were no significant differences in the extent of tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3 in response to any of the receptors examined, suggesting that there is redundancy at the level of receptor activation of Vav proteins. The strong homology between the SH2 domains of Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3 may explain why all three proteins respond similarly to receptor tyrosine kinase activation. Because the SH2 domain of Vav1 (5, 29) or Vav2 (33) is sufficient to mediate the interaction between these Vav isoforms and tyrosine-phosphorylated growth factor receptors, and because Vav1, Vav2, and Vav3 proteins efficiently coprecipitated with activated growth factor receptors in our study, it is likely that the SH2 domain of each Vav protein mediates direct interactions with growth factor receptors. In addition, we have found that a glutathione S-transferase fusion protein containing the carboxyl-terminal adapter domain (SH3-SH2-SH3) of Vav2 can bind to tyrosine-phosphorylated PDGFβR immobilized on a filter membrane, indicating that Vav2 can bind directly to the PDGFR (Moores and Brugge, unpublished).

Surprisingly, there are multiple individual tyrosine residues on the activated PDGFβR that are able to mediate Vav2 tyrosine phosphorylation. The sequences near each of these residues on the PDGFβR are consistent with the binding preferences defined for Vav1 SH2 ligands—either Met in position +1 relative to the phosphorylated tyrosine or Pro in position +3 (39). Notably, the site on PDGFβR that did not mediate Vav2 tyrosine phosphorylation (Y1009) does not contain either of these residues in the +1 or +3 position. Because multiple tyrosine residues on PDGFβR are capable of mediating Vav2 tyrosine phosphorylation, it is predicted that removing a single tyrosine residues in PDGFβR will not inhibit downstream pathways controlled by Vav. Additionally, because Vav proteins share binding sites on PDGFβR with other proteins such as PI 3′-kinase, RasGAP, and PLCγ1, overexpression of a catalytically inactive form of Vav would likely interfere with multiple signaling pathways downstream of the PDGFβR.

Although there were no significant differences in induction of tyrosine phosphorylation of the three Vav isoforms investigated in this study, there may be differences in downstream effectors of each Vav protein. Such differences could explain why Vav1-deficient mice display defects in TCR-mediated signaling despite the evidence that all three isoforms of Vav are expressed in T cells and are inducibly phosphorylated following stimulation of the TCR in Jurkat T cells (Fig. 5C and reference (32). We have demonstrated that one difference between the three Vav proteins is in their abilities to potentiate NFAT- and NFκB-dependent transcriptional activity in response to TCR stimulation. Overexpression of Vav1 dramatically potentiated antigen-induced activation of NFAT relative to overexpression of Vav2 or Vav3. This result provides at least one explanation for the specific defect in NFAT activation in vav1−/− T cells.

Enhancement of a distinct transcriptional pathway, that involving NFκB, showed a different pattern of Vav isoform specificity. Overexpression of either Vav1 or Vav3, but not Vav2, was able to potentiate antigen-induced activation of NFκB. In the context of our overexpression experiments in Jurkat T cells, we cannot distinguish if the potentiation of NFκB-dependent transcription by Vav1 or Vav3 is due to the use of common or alternative components of the TCR signaling apparatus. The evidence that Vav1-deficient T cells display a partial loss of NFκB activity (7) suggests that Vav3 is not able to fully compensate for the loss of Vav1. Taken together, these results suggest that each Vav family member displays isoform-specific differences in the activation of downstream signaling pathways.

It is not clear which Vav functional domains are necessary to activate NFAT. Surprisingly, the GDP/GTP exchange activity of Vav1 is not required for NFAT-dependent transcription (26). Deletion of the first 67 residues of Vav1, however, abolishes its ability to synergize with TCR engagement to enhance NFAT-dependent transcription in Jurkat T cells (20, 49), suggesting that this amino-terminal region may be required for activation of NFAT. This region of Vav1 is not likely to be sufficient for NFAT activation because overexpression of the amino-terminal region alone or a Vav1 protein lacking the carboxyl-terminal adapter domain (SH3-SH2-SH3) does not reproduce the effect of full-length Vav1 (49). In addition, the carboxy-terminal adapter domain of Vav1 alone is not sufficient for enhanced NFAT activation because overexpression of this domain also fails to potentiate NFAT activity in Jurkat T cells (50). Thus, there are likely to be multiple regions of Vav1 that are necessary to induce NFAT-dependent transcription.

Differences in the substrate specificity of the guanine nucleotide exchange domain of each Vav protein could provide one explanation for differential Vav protein signaling to downstream pathways. The preferences of each Vav protein for the different Rho GTPases are unclear, as conflicting results have been reported (1, 8, 15, 16, 32, 38). In addition, the N-SH3 domains of the three Vav proteins not only diverge from the consensus SH3 domain but also differ from each other and thus may result in different interactions with downstream signaling molecules. Likewise, the differences in the polyproline sequences of each Vav protein may also specify binding to distinct SH3 domains. Differences in expression levels of each Vav protein in distinct cell types may also determine the extent to which Vav-mediated cellular events are activated following receptor engagement. There may also be differences in localization or compartmentalization between the Vav proteins that affect their functions in cells where multiple Vav proteins are expressed.

Because Vav proteins activate Rho GTPases, it is likely that these proteins directly couple receptor activation to downstream rearrangements of the actin cytoskeleton. Indeed, one defect in vav1−/− T cells is in patching and capping of TCRs, an event dependent on actin polymerization. We have shown that Vav proteins are tyrosine phosphorylated in response to activation of diverse receptors at the cell surface. Other studies have demonstrated that Vav proteins have the ability to reorganize the actin cytoskeleton through activation of Rho family GTPases (3, 46). Thus, Vav proteins are likely to be critical integrators of receptor signals and direct effectors of the changes in the actin cytoskeleton involved in cellular adhesion, migration, and invasion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Orkin for the vav-related cDNA fragment, A. Altman and D. Kwiatkowski for vav cDNA plasmids, T. Roberts for the 4G10 antibody, M. Ginsberg for the A5 CHO cell line, and R. Xavier and B. Seed for the SV40κB-luc plasmid. We are especially grateful to A. Kazlauskas for HepG2 cell lines expressing PDGFβR variants. We also thank A. Kazlauskas and S. Munroe for critical comments on the manuscript and helpful discussions.

S.L.M. was supported in part by the Cancer Research Fund of the Damon Runyon-Walter Winchell Foundation, grant DRG-1516. F.W.A. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. W.S. is a recipient of the Arthritis Foundation Hulda Irene Duggan Investigator Award. These studies were supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA78773 to J.S.B.) and (AI20047 and PO1 HL59561 to F.W.A.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe K, Rossman K L, Liu B, Ritola K D, Chiang D, Campbell S L, Burridge K, Der C J. Vav2 is an activator of Cdc42, Rac1, and RhoA. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10141–10149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams J M, Houston H, Allen J, Lints T, Harvey R. The hematopoietically expressed vav proto-oncogene shares homology with the dbl GDP-GTP exchange factor, the bcr gene and a yeast gene (CDC24) involved in cytoskeletal organization. Oncogene. 1992;7:611–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bustelo X R. Regulatory and signaling properties of the Vav family. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1461–1477. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1461-1477.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bustelo X R, Barbacid M. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the vav proto-oncogene product in activated B cells. Science. 1992;256:1196–1199. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5060.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bustelo X R, Ledbetter J A, Barbacid M. Product of vav proto-oncogene defines a new class of tyrosine protein kinase substrates. Nature. 1992;356:68–71. doi: 10.1038/356068a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cichowski K, Brugge J S, Brass L F. Thrombin receptor activation and integrin engagement stimulate tyrosine phosphorylation of the proto-oncogene product, p95vav, in platelets. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7544–7550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costello P S, Walters A E, Mee P J, Turner M, Reynolds L F, Prisco A, Sarner N, Zamoyska R, Tybulewicz V L. The Rho-family GTP exchange factor Vav is a critical transducer of T cell receptor signals to the calcium, ERK, and NF-kappaB pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3035–3040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crespo P, Schuebel K E, Ostrom A A, Gutkind J S, Bustelo X R. Phosphotyrosine-dependent activation of Rac-1 GDP/GTP exchange by the vav proto-oncogene product. Nature. 1997;385:169–172. doi: 10.1038/385169a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deckert M, Tartare-Deckert S, Couture C, Mustelin T, Altman A. Functional and physical interactions of Syk family kinases with the Vav proto-oncogene product. Immunity. 1996;5:591–604. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80273-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eck M J, Shoelson S E, Harrison S C. Recognition of a high-affinity phosphotyrosyl peptide by the Src homology-2 domain of p56lck. Nature. 1993;362:87–91. doi: 10.1038/362087a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng S, Chen J K, Yu H, Simon J A, Schreiber S L. Two binding orientations for peptides to the Src SH3 domain: development of a general model for SH3-ligand interactions. Science. 1994;266:1241–1247. doi: 10.1126/science.7526465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer K D, Kong Y Y, Nishina H, Tedford K, Marengere L E, Kozieradzki I, Sasaki T, Starr M, Chan G, Gardener S, Nghiem M P, Bouchard D, Barbacid M, Bernstein A, Penninger J M. Vav is a regulator of cytoskeletal reorganization mediated by the T-cell receptor. Curr Biol. 1998;8:554–562. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70224-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer K D, Zmuldzinas A, Gardner S, Barbacid M, Bernstein A, Guidos C. Defective T-cell receptor signalling and positive selection of Vav-deficient CD4+ CD8+ thymocytes. Nature. 1995;374:474–477. doi: 10.1038/374474a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gotoh A, Takahira H, Geahlen R L, Broxmeyer H E. Cross-linking of integrins induces tyrosine phosphorylation of the proto-oncogene product Vav and the protein tyrosine kinase Syk in human factor-dependent myeloid cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1997;8:721–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han J, Das B, Wei W, Van Aelst L, Mosteller R D, Khosravi-Far R, Westwick J K, Der C J, Broek D. Lck regulates Vav activation of members of the Rho family of GTPases. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1346–1353. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han J, Luby-Phelps K, Das B, Shu X, Xia Y, Mosteller R D, Krishna U M, Falck J R, White M A, Broek D. Role of substrates and products of PI 3-kinase in regulating activation of Rac-related guanosine triphosphatases by Vav. Science. 1998;279:558–560. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hedin K E, Bell M P, Kalli K R, Huntoon C J, Sharp B M, McKean D J. Delta-opioid receptors expressed by Jurkat T cells enhance IL-2 secretion by increasing AP-1 complexes and activity of the NF-AT/AP-1- binding promoter element. J Immunol. 1997;159:5431–5440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henske E P, Short M P, Jozwiak S, Bovey C M, Ramlakhan S, Haines J L, Kwiatkowski D J. Identification of VAV2 on 9q34 and its exclusion as the tuberous sclerosis gene TSC1. Ann Hum Genet. 1995;59:25–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1995.tb01603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hofmann T G, Hehner S P, Droge W, Schmitz M L. Caspase-dependent cleavage and inactivation of the Vav1 proto-oncogene product during apoptosis prevents IL-2 transcription. Oncogene. 2000;19:1153–1163. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holsinger L J, Graef I A, Swat W, Chi T, Bautista D M, Davidson L, Lewis R S, Alt F W, Crabtree G R. Defects in actin-cap formation in Vav-deficient mice implicate an actin requirement for lymphocyte signal transduction. Curr Biol. 1998;8:563–572. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaplan K B, Swedlow J R, Morgan D O, Varmus H E. c-Src enhances the spreading of src−/− fibroblasts on fibronectin by a kinase-independent mechanism. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1505–1517. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.12.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katzav S, Cleveland J L, Heslop H E, Pulido D. Loss of the amino-terminal helix-loop-helix domain of the vav proto-oncogene activates its transforming potential. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:1912–1920. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.4.1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katzav S, Martin-Zanca D, Barbacid M. vav, a novel human oncogene derived from a locus ubiquitously expressed in hematopoietic cells. EMBO J. 1989;8:2283–2290. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kazlauskas A, Feng G S, Pawson T, Valius M. The 64-kDa protein that associates with the platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta subunit via Tyr-1009 is the SH2-containing phosphotyrosine phosphatase Syp. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6939–6943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.6939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kozak M. An analysis of 5′-noncoding sequences from 699 vertebrate messenger RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:8125–8148. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.20.8125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuhne M R, Ku G, Weiss A. A guanine nucleotide exchange factor-independent function of Vav1 in transcriptional activation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2185–2190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leong L, Hughes P E, Schwartz M A, Ginsberg M H, Shattil S J. Integrin signaling: roles for the cytoplasmic tails of alpha IIb beta 3 in the tyrosine phosphorylation of pp125FAK. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:3817–3825. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.12.3817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis J M, Baskaran R, Taagepera S, Schwartz M A, Wang J Y. Integrin regulation of c-Abl tyrosine kinase activity and cytoplasmic-nuclear transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:15174–15179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Margolis B, Hu P, Katzav S, Li W, Oliver J M, Ullrich A, Weiss A, Schlessinger J. Tyrosine phosphorylation of vav proto-oncogene product containing SH2 domain and transcription factor motifs. Nature. 1992;356:71–74. doi: 10.1038/356071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michel F, Grimaud L, Tuosto L, Acuto O. Fyn and ZAP-70 are required for Vav phosphorylation in T cells stimulated by antigen-presenting cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31932–31938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.31932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miranti C K, Leng L, Maschberger P, Brugge J S, Shattil S J. Identification of a novel integrin signaling pathway involving the kinase Syk and the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Vav1. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1289–1299. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00559-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Movilla N, Bustelo X R. Biological and regulatory properties of Vav-3, a new member of the Vav family of oncoproteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7870–7885. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.11.7870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pandey A, Podtelejnikov A V, Blagoev B, Bustelo X R, Mann M, Lodish H F. Analysis of receptor signaling pathways by mass spectrometry: Identification of Vav-2 as a substrate of the epidermal and platelet- derived growth factor receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:179–184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richardson A, Parsons J T. Signal transduction through integrins: a central role for focal adhesion kinase? Bioessays. 1995;17:229–236. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romero F, Fischer S. Structure and function of vav. Cell Signal. 1996;8:545–553. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(96)00118-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salojin K V, Zhang J, Delovitch T L. TCR and CD28 are coupled via ZAP-70 to the activation of the Vav/Rac-1- /PAK-1/p38 MAPK signaling pathway. J Immunol. 1999;163:844–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schuebel K E, Bustelo X R, Nielsen D A, Song B J, Barbacid M, Goldman D, Lee I J. Isolation and characterization of murine vav2, a member of the vav family of proto-oncogenes. Oncogene. 1996;13:363–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schuebel K E, Movilla N, Rosa J L, Bustelo X R. Phosphorylation-dependent and constitutive activation of Rho proteins by wild-type and oncogenic Vav-2. EMBO J. 1998;17:6608–6621. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Songyang Z, Shoelson S E, McGlade J, Olivier P, Pawson T, Bustelo X R, Barbacid M, Sabe H, Hanafusa H, Yi T, et al. Specific motifs recognized by the SH2 domains of Csk, 3BP2, fps/fes, GRB-2, HCP, SHC, Syk, and Vav. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2777–2785. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanaka M, Herr W. Differential transcriptional activation by Oct-1 and Oct-2: interdependent activation domains induce Oct-2 phosphorylation. Cell. 1990;60:375–386. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90589-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tarakhovsky A, Turner M, Schaal S, Mee P J, Duddy L P, Rajewsky K, Tybulewicz V L. Defective antigen receptor-mediated proliferation of B and T cells in the absence of Vav. Nature. 1995;374:467–470. doi: 10.1038/374467a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teramoto H, Salem P, Robbins K C, Bustelo X R, Gutkind J S. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the vav proto-oncogene product links FcepsilonRI to the Rac1-JNK pathway. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10751–10755. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ting A T, Pimentel-Muinos F X, Seed B. RIP mediates tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 activation of NF-kappaB but not Fas/APO-1-initiated apoptosis. EMBO J. 1996;15:6189–6196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valius M, Kazlauskas A. Phospholipase C-gamma 1 and phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase are the downstream mediators of the PDGF receptor's mitogenic signal. Cell. 1993;73:321–334. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90232-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valius M, Secrist J P, Kazlauskas A. The GTPase-activating protein of Ras suppresses platelet-derived growth factor beta receptor signaling by silencing phospholipase C-γ 1. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3058–3071. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Aelst L, D'Souza-Schorey C. Rho GTPases and signaling networks. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2295–2322. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.18.2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wadzinski B E, Eisfelder B J, Peruski L F, Jr, Mumby M C, Johnson G L. NH2-terminal modification of the phosphatase 2A catalytic subunit allows functional expression in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:16883–16888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Waksman G, Shoelson S E, Pant N, Cowburn D, Kuriyan J. Binding of a high affinity phosphotyrosyl peptide to the Src SH2 domain: crystal structures of the complexed and peptide-free forms. Cell. 1993;72:779–790. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90405-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu J, Katzav S, Weiss A. A functional T-cell receptor signaling pathway is required for p95vav activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4337–4346. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu J, Motto D G, Koretzky G A, Weiss A. Vav and SLP-76 interact and functionally cooperate in IL-2 gene activation. Immunity. 1996;4:593–602. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80485-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ye Z S, Baltimore D. Binding of Vav to Grb2 through dimerization of Src homology 3 domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12629–12633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yron I, Deckert M, Reff M E, Munshi A, Schwartz M A, Altman A. Integrin-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation and growth regulation by Vav. Cell Adhes Commun. 1999;7:1–11. doi: 10.3109/15419069909034388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu H, Chen J K, Feng S, Dalgarno D C, Brauer A W, Schreiber S L. Structural basis for the binding of proline-rich peptides to SH3 domains. Cell. 1994;76:933–945. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang R, Alt F W, Davidson L, Orkin S H, Swat W. Defective signalling through the T- and B-cell antigen receptors in lymphoid cells lacking the vav proto-oncogene. Nature. 1995;374:470–473. doi: 10.1038/374470a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zheng L, Sjolander A, Eckerdal J, Andersson T. Antibody-induced engagement of beta 2 integrins on adherent human neutrophils triggers activation of p21ras through tyrosine phosphorylation of the protooncogene product Vav. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8431–8436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]