Abstract

Background:

Investigators have attempted to derive tools that could provide clinicians with an easily-obtainable estimate of the chance of vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) for those who undertake trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC). One tool that subsequently was validated externally was derived from data from the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Cesarean Registry. Concern has been raised, however, that this tool includes the socially-constructed variables of race and ethnicity.

Objective:

To develop an accurate tool to predict VBAC, using data easily obtainable early in pregnancy, without the inclusion of race/ethnicity.

Study Design:

This is a secondary analysis of the Cesarean Registry of the MFMU Network. The approach to the present analysis is similar to that of the analysis in which the prior VBAC prediction tool was derived. Specifically, individuals were included in this analysis if they were delivered on or after 37 0/7 weeks’ gestation with a live singleton cephalic fetus at the time of labor and delivery admission, had a TOLAC, and had history of one prior low-transverse cesarean delivery. Information was only considered for inclusion in the model if it was ascertainable at an initial prenatal visit. Model selection and internal validation were performed using a cross-validation procedure, with the dataset randomly and equally divided into a training set and a test set. The training set was used to identify factors associated with VBAC and build the logistic regression predictive model using stepwise backward elimination. A final model was generated that included all variables found to be significant (p<0.05). The accuracy of the model to predict VBAC was assessed using the c-index. The independent test set was used to estimate classification errors and validate the model that had been developed from the training set, and calibration was assessed. The final model was then applied to the overall analytic population.

Results:

Of the 11,687 individuals who met inclusion criteria for this secondary analysis, VBAC occurred in 8636 (74%). The backward-elimination variable selection yielded a model from the training set that included maternal age, pre-pregnancy weight, height, indication for prior cesarean, obstetric history, and chronic hypertension. VBAC was significantly more likely for those who were taller and had a prior vaginal birth, particularly if that vaginal birth had occurred after the prior cesarean. Conversely, VBAC was significantly less likely among those whose age was older, whose weight was heavier, whose indication for prior cesarean was arrest of dilation or descent, and who had a history of medication-treated chronic hypertension. The model had excellent calibration between predicted and empirical probabilities and, when applied to the overall analytic population, an AUC of 0.75 (95% CI: 0.74 – 0.77), which is similar to the AUC of the previous model (0.75) that included race/ethnicity.

Conclusion:

We successfully derived an accurate model (available at https://mfmunetwork.bsc.gwu.edu/web/mfmunetwork/vaginal-birth-after-cesarean-calculator), which did not include race or ethnicity, for estimation of VBAC probability.

Keywords: trial of labor after cesarean, vaginal birth after cesarean, prediction, calibration, validation, personalized, calculator

Condensation:

A well-calibrated prediction model for likelihood of vaginal birth after cesarean that does not include race and ethnicity was developed.

Introduction

After peaking in the late 1990’s, vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) rates dropped sharply in the United States and continue to remain below 10%.1 This decline has been attributed largely to a decline in the frequency with which individuals choose to undergo trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC).2 One analysis performed in the years following the VBAC peak revealed that the magnitude of the decline in TOLAC was similar regardless of the likelihood that an individual would have a VBAC if they undertook TOLAC.2

The choice to undertake a TOLAC is one that should be person centered and a product of shared decision making that incorporates an individual’s values and preferences.3,4 Ideally, the decision process regarding the approach to delivery should be started early in pregnancy, and part of that process should be the provision of information, such as the likelihood that a VBAC will occur if TOLAC is undertaken. While one approach is to provide a population-level estimate of VBAC probability, another approach is to provide a more individualized estimate.

Accordingly, investigators have attempted to derive tools that could be used to provide clinicians with an easily-obtainable estimate of VBAC for those who undertake TOLAC.5–8 One internally-validated tool that subsequently has been validated externally in multiple different locations at temporally distinct times was derived from data from the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Cesarean Registry.9–16 This tool, however, included the socially-constructed variables of race and ethnicity, and there is concern that their inclusion may reify a biologic construct of race/ethnicity and perpetuate health disparities.17–19 This analysis, therefore, was designed to determine whether an internally-validated tool to accurately predict VBAC using data easily obtainable early in pregnancy, without the inclusion of race/ethnicity, could be derived using the same MFMU dataset.

Methods

This is a secondary analysis of the Cesarean Registry of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development MFMU Network. The registry included all those with a history of cesarean delivery who were admitted for delivery to centers within MFMU participating centers between 1999 and 2002. Full details of this study have been described previously.20 In brief, trained and certified research nurses abstracted medical records of women who were identified as having had any history of cesarean delivery. Abstracted data included demographic, historical, and peripartum factors. Approval for the study was obtained from the institutional review board of each institution, and a waiver of informed consent was obtained.

The general approach to the present analysis is similar to that of the analysis in which the prior VBAC prediction tool was derived.9 Specifically, women were included in this analysis if they were delivered on or after 37 0/7 weeks gestation with a live singleton fetus in the cephalic presentation at the time of labor and delivery admission, had a TOLAC, and had history of one prior low-transverse cesarean delivery. Women were excluded if they had a prior myomectomy. Given the value of beginning counseling early in pregnancy, information was only considered for inclusion in the model if it was ascertainable at an initial prenatal visit. Such factors included demographic characteristics (age, height, pre-pregnancy weight, pre-pregnancy body mass index [BMI]), medical conditions existing prior to pregnancy (chronic hypertension treated with medication prior to and during pregnancy, diabetes, asthma, thyroid disease, seizure disorder, renal disease, cardiac disease, connective tissue disease), and obstetric history (presence of prior vaginal delivery, arrest disorder as the indication for prior cesarean delivery, and maximal prior birth weight). If an individual had a prior vaginal delivery, it was further characterized by whether it had occurred after the prior cesarean, with no prior vaginal birth used as the referent. An arrest disorder for cesarean delivery was considered to exist when the primary indication for a previous cesarean was an arrest of dilation or descent, and included those indications coded as “failed induction”.

Model selection and internal validation were performed using a cross-validation procedure. All those meeting eligibility criteria (i.e., one prior low-transverse cesarean delivery and trial of labor on or after 37 weeks with a vertex singleton) were randomly divided into a mutually-exclusive training set (n= 5,741) and test (validation) set (n=5,946). The training set was used to identify factors associated with VBAC and build the logistic regression predictive model, which was developed using stepwise backward elimination with the inclusion of all factors found to be significant (p<0.05). Linear and quadratic terms for continuous variables and two-way interactions also were evaluated for inclusion in this model.

The individuals in the test set were then used to estimate classification errors and validate the model that had been developed using the training set, with calibration assessed graphically. The predicted probabilities of VBAC using the test set were calculated and partitioned into deciles. In each decile, the proportion (and the corresponding 95% confidence interval [CI]) of individuals who had a VBAC was calculated. These proportions represent the observed (empirical) probability of VBAC. A penalized B-spline curve for the proportions and CIs were then generated based on the predicted and observed probabilities for each decile category.

Final estimates of the coefficients for each factor in the logistic regression predictive model were then determined using all individuals included in this analysis (i.e., the overall analytic population). For each factor in the model, the associations with VBAC were reported as adjusted odds ratios (with corresponding 95% CI). The ability of the model to accurately predict VBAC was assessed using the c-index, which is a measure that is the equivalent of the area under the receiver-operating-characteristic curve (AUC).

To describe the probability of VBAC across various characteristics that were significant in the final model, probabilities for combinations of characteristics that were frequent in the cohort were calculated. For each scenario, the percent probability and Wald-test-based CIs of VBAC were estimated.

No imputation for missing values was performed. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

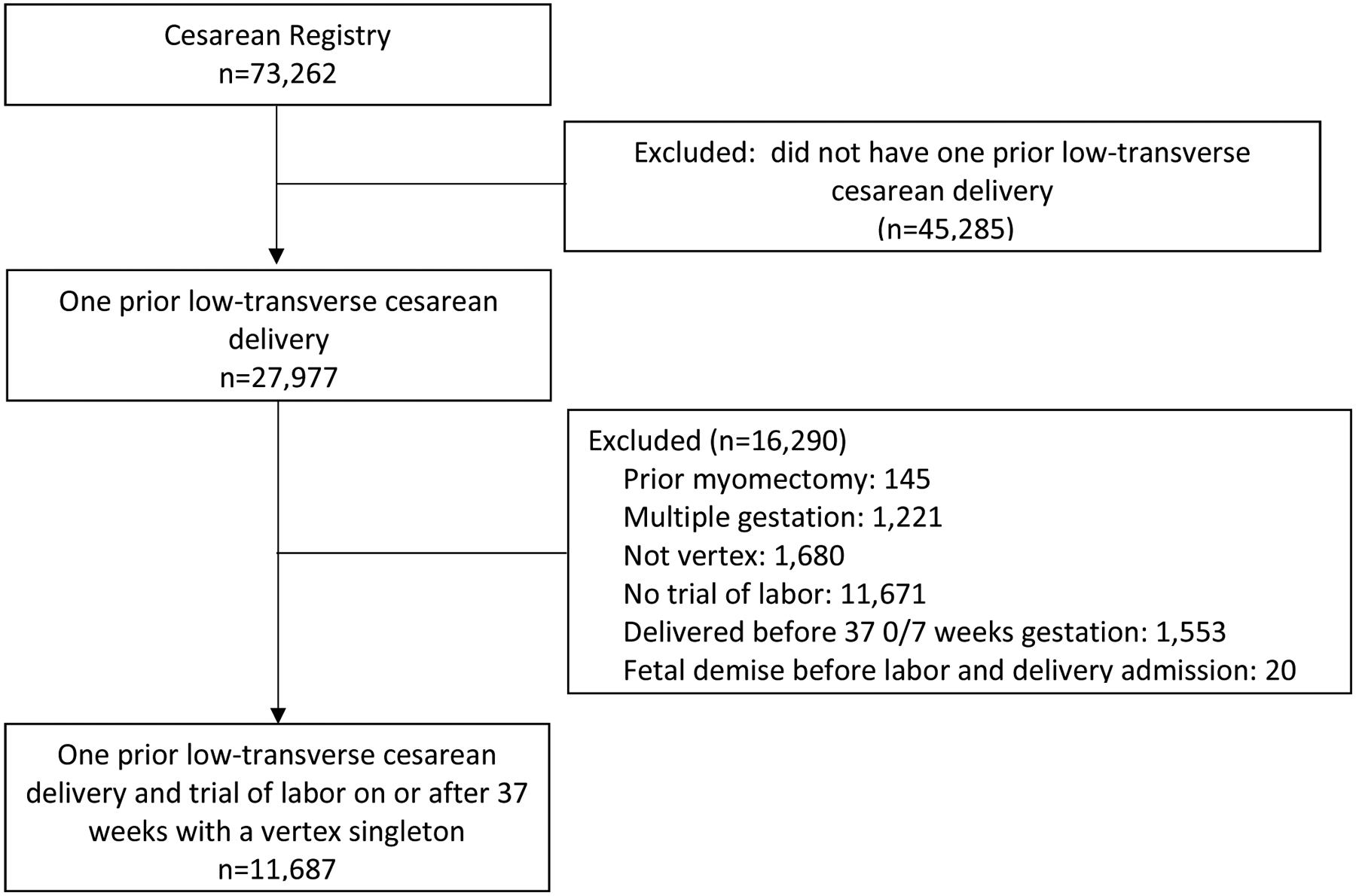

Of the 11,687 individuals (Figure 1) who met inclusion criteria for this secondary analysis, VBAC occurred in 8636 (74%). Characteristics of the cohort are presented in Table 1. As illustrated, they were diverse with respect to their demographic characteristics, as well as their medical and obstetric history. They were diverse as well with respect to their reported race/ethnicity: 4239 (36.3%) non-Hispanic Black, 4528 (38.7%) non-Hispanic White, 2325 (19.9%) Hispanic, 227 (1.9%) Asian, and 368 (3.1%) other.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of eligibility for inclusion in this secondary analysis

Table 1.

Characteristics of the population

| (n=11,687) | |

|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 28.6 ± 5.8 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 26.4 ± 6.3 |

| Pre-pregnancy weight (kg) | 69.5 ± 17.3 |

| Height (cm) | 162.2 ± 7.6 |

| Arrest disorder indication for prior cesarean | 3984 (34.1) |

| Obstetric history | |

| No previous vaginal delivery | 6068 (54.4) |

| Previous vaginal delivery only before prior cesarean | 1456 (13.0) |

| Previous VBAC | 3636 (32.6) |

| Maximum birth weight of prior child (grams) | 3,405 ± 635 |

| Pre-gestational diabetes | 91 (0.8) |

| Asthma | 842 (7.2) |

| History of thyroid disease | 291 (2.5) |

| History of seizure disorder | 91 (0.8) |

| Treated chronic hypertension | 144 (1.2) |

| History of renal disease | 70 (0.6) |

| History of heart disease | 129 (1.1) |

| History of connective tissue disorder | 50 (0.4) |

BMI, body mass index, VBAC, vaginal birth after cesarean.

Data are mean ± standard deviation, or n (%).

Number of missing values: pre-pregnancy BMI (n=3809), pre-pregnancy weight (n=3591), height (n=531), obstetric history (n=527), birth weight of prior child (n=824).

The backward-elimination variable selection applied to the training set yielded a model (Table 2; AUC 0.76 [95%CI: 0.74 – 0.78]) that included maternal age, pre-pregnancy weight, height, indication for prior cesarean, obstetric history, and treated chronic hypertension. VBAC was significantly more likely for those who were taller and had a prior vaginal birth, particularly if that vaginal birth had occurred after the prior cesarean. Conversely, VBAC was significantly less likely among those whose age was older, whose weight was heavier, whose indication for prior cesarean was an arrest disorder, and who had a history of treated chronic hypertension.

Table 2.

Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of factors associated with vaginal birth after cesarean

| Training set (n=5,741*) |

Test (validation) set (n=5,946*) |

Overall analytic population (n=7,712) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) |

| Maternal age, per 1-year increase | 0.97 (0.96 – 0.99) | 0.98 (0.97 – 1.00) | 0.98 (0.97 – 0.99) |

| Pre-pregnancy weight, per 1-kg increase | 0.98 (0.97 – 0.98) | 0.98 (0.97 – 0.98) | 0.98 (0.97 – 0.98) |

| Height, per 1-cm increase | 1.06 (1.05 – 1.07) | 1.05 (1.04 – 1.07) | 1.06 (1.05 – 1.07) |

| Arrest disorder indication for prior cesarean | 0.54 (0.46 – 0.63) | 0.57 (0.48 – 0.67) | 0.55 (0.49 – 0.62) |

| Obstetric history | |||

| No previous vaginal delivery | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) |

| Previous vaginal delivery only before prior cesarean | 2.96 (2.27 – 3.85) | 1.96 (1.54 – 2.49) | 2.38 (2.00 – 2.85) |

| Previous VBAC | 6.52 (5.22 – 8.14) | 6.50 (5.18 – 8.14) | 6.48 (5.54 – 7.59) |

| Treated chronic hypertension | 0.37 (0.18 – 0.74) | 0.38 (0.20 – 0.75) | 0.38 (0.24 – 0.61) |

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval, VBAC, vaginal birth after cesarean.

Chance of vaginal birth after cesarean in analytic group: 73.8%, training set; 74.0%, test set; 73.9%, overall analytic population

n=1,961 in the training set and n=2,014 in the validation set with missing data for the variables in the final multivariable model.

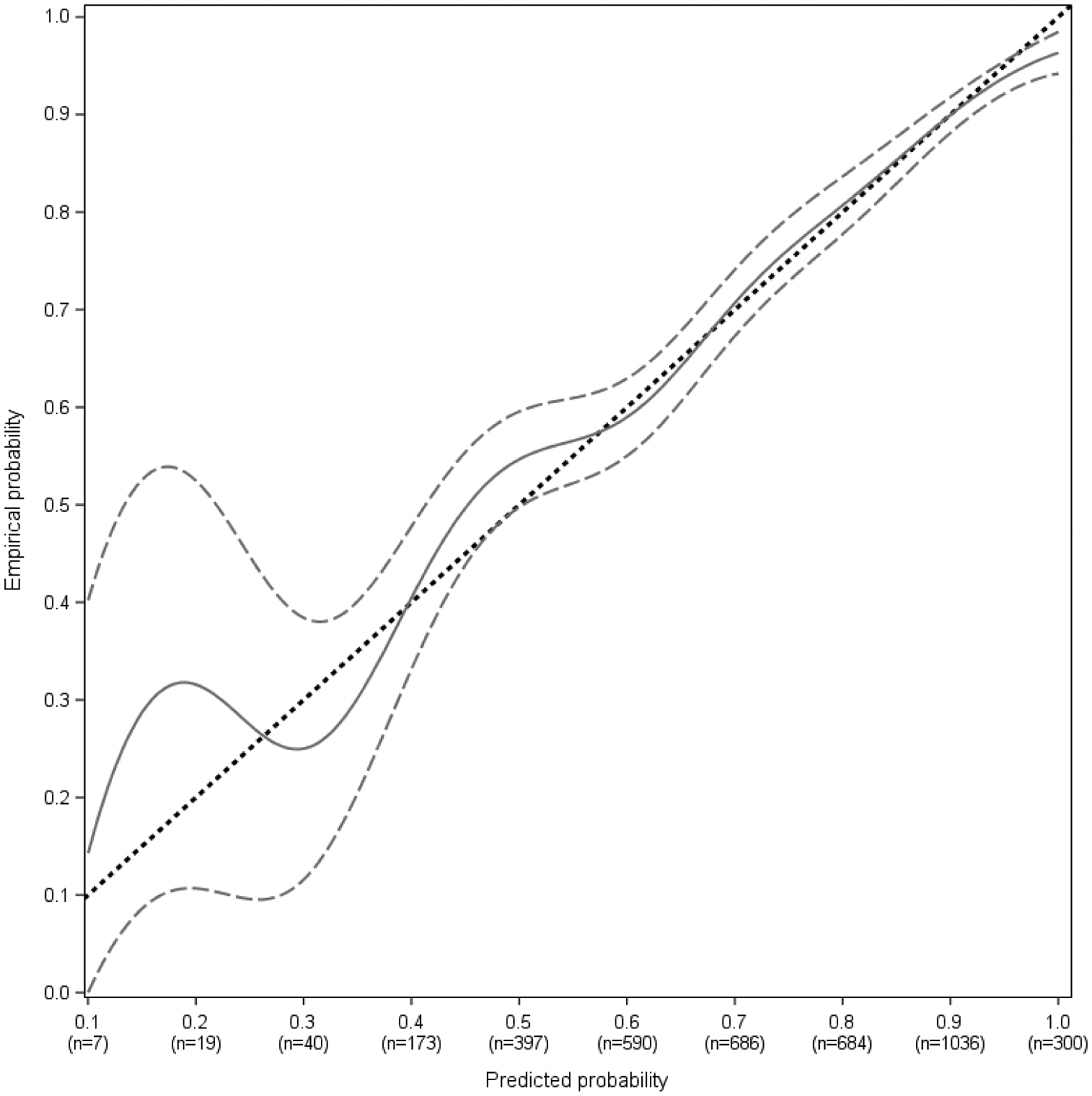

For individuals included in the test (validation) set, the associations of each significant factor with VBAC were similar to the associations with VBAC among individuals in the training set (Table 2), and the correspondingly AUC (0.75 [95% CI: 0.73 – 0.76]) was similar as well. The related calibration results with the estimated curve and its 95% confidence band confirmed that the predicted probabilities for VBAC were overall consistent with the empirical probabilities (Figure 2). As illustrated, the predicted probability of VBAC largely adhered to the observed probability of VBAC, with narrow confidence intervals, along a large range of predicted probability values, and only begins to deviate to any degree when the chance of VBAC is less than 40% (at which point there are very few individuals with such probabilities).

Figure 2.

Calibration curve (with 95% confidence interval) of model validation in the test set

The dashed straight line is the line of perfect calibration. The solid curve is the calibration curve generated by the prediction model, which is surrounded by dashed curves that represent the 95% confidence band of the calibration curve.

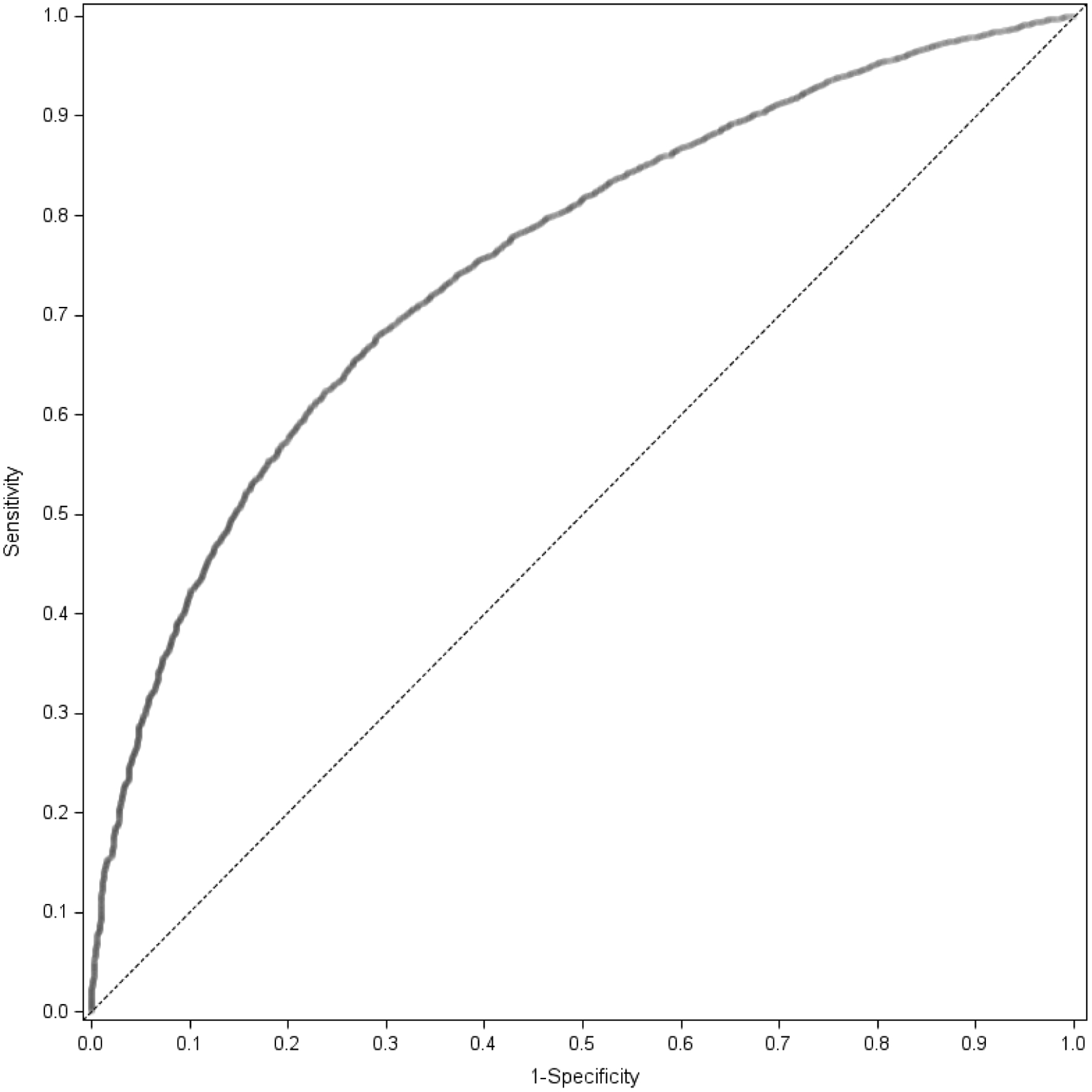

Using all individuals in the analytic cohort, the regression is as follows: predicted probability (%) of VBAC = (exp(w)/[1+exp(w)]) * 100, where w = −5.952 − 0.023(age) − 0.024(pre-pregnancy weight, kg) + 0.056(height, cm) − 0.597(arrest indication) + 0.868(previous vaginal delivery only before prior cesarean) + 1.869(previous VBAC) − 0.966(treated chronic hypertension); and with arrest indication, previous vaginal delivery only before prior cesarean, previous VBAC, and treated chronic hypertension coded as 0 for “no” and 1 for “yes”. This final equation yields the odds ratios (95% CI) in Table 2, and an AUC of 0.75 (95% CI: 0.74 – 0.77; Figure 3). The proportion who had a VBAC among those in the final analytic cohort (i.e., only individuals without missing values for all final variables in the model) and those with missing data for final variables in the model was not significantly different (5,699/7,712 (74%) vs. 2,937/3,975 (74%), p=0.99).

Figure 3.

Receiver-operating characteristic curve of the prediction model for vaginal birth after cesarean based on the overall analytic population

Table 3 shows predicted probabilities of VBAC, based on the final model in the overall analytic population, for 12 different scenarios for a variety of individuals with different characteristics ascertainable at an initial prenatal visit. As illustrated, depending upon the combination of these characteristics, the predicted chance of VBAC varies widely. A web-based calculator, derived from the final regression equation, that generates individualized results such as those provided in Table 3, is available at https://mfmunetwork.bsc.gwu.edu/web/mfmunetwork/vaginal-birth-after-cesarean-calculator.

Table 3.

Predicted probabilities for vaginal birth after cesarean for 12 hypothetical individuals*

| Example | Maternal age (years) | Pre-pregnancy weight (kg) | Height (cm) | Arrest disorder indication for prior cesarean | Prior vaginal delivery | Chronic hypertension | Predicted % probability of VBAC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 | 71 | 171 | No | Previous VBAC | No | 95.6 (94.9 – 96.3) |

| 2 | 30 | 71 | 156 | No | Previous VBAC | No | 90.5 (89.0 – 91.7) |

| 3 | 30 | 71 | 156 | No | Previous vaginal delivery only before prior cesarean | No | 77.7 (74.7 – 80.5) |

| 4 | 30 | 71 | 171 | No | No | No | 77.2 (75.2 – 79.0) |

| 5 | 30 | 44 | 156 | No | No | No | 73.4 (71.1 – 75.6) |

| 6 | 23 | 71 | 156 | No | No | No | 63.3 (60.8 – 65.8) |

| 7 | 30 | 71 | 156 | No | No | No | 59.4 (57.0 – 61.8) |

| 8 | 37 | 71 | 156 | No | No | No | 55.4 (52.1 – 58.7) |

| 9 | 23 | 71 | 156 | Yes | No | No | 48.7 (46.0 – 51.4) |

| 10 | 30 | 71 | 156 | Yes | No | No | 44.6 (42.2 – 47.1) |

| 11 | 30 | 71 | 156 | No | No | Yes | 35.8 (25.6 – 47.4) |

| 12 | 37 | 71 | 156 | No | No | Yes | 32.1 (22.6 – 43.5) |

VBAC, vaginal birth after cesarean.

Based on the overall analytic population.

Discussion

Principal Findings

In this analysis, we have developed a model that estimates the probability of a VBAC if an individual chooses to have a TOLAC. In contrast to a prior model based on MFMU data that incorporated a race/ethnicity variable,10 this model was evaluated without the inclusion of race, ethnicity, or other socially-defined constructs.

Results in the Context of What is Known

We have shown that, using the same data source and methodologic approach, a model can be developed that is quite similar in terms of its input variables – in fact, all variables in the prior model were retained, with one additional variable (chronic hypertension) identified. The classification ability of the new model is similar to that of the prior model as well (AUC of 0.75 for both), and it demonstrates excellent calibration across a large range of predicted VBAC estimates. Indeed, the calibration curve, even more so than the AUC, gives particular insight into the potential value of a model that is designed to provide individual probability estimates in order to assist with decision making.21

Clinical implications

There is a strong theoretical underpinning for believing that the estimate provided by such a model would be of value to individuals considering whether undergoing a TOLAC is the approach that is best for them. For some individuals, the desire to undertake a TOLAC is informed by the likelihood that it will result in a vaginal birth and the strength of their preference for that outcome.22 Because the majority of maternal and perinatal morbidity in the setting of TOLAC occurs among those who ultimately have a cesarean,23 and the chance of morbidity is highly related to the VBAC probability,24 this estimation also can be informative regarding other important health outcomes. From a person-centered standpoint, an estimation that is personalized versus a population mean should be preferable.

Research Implications

Regardless of the test characteristics of this model, it can only potentially serve its intended purpose of enhancing person-centered care if it is understood and used appropriately. This model is designed to estimate the chance of a clinical event and not a physiologic standard; thus, it is not designed to demonstrate inherent or inevitable associations between particular factors and the chance of VBAC. If obstetric care patterns were to change or vary significantly such that the chance of VBAC after a TOLAC were to differ as well, a different model would need to be developed in order to retain accuracy. Also, this model is not designed to uncover individual factors or produce a summary probability estimate that indicates someone should or should not undergo a TOLAC. It is a model designed to provide an estimate of the chance of VBAC that can be used by people and their providers to assist in an informed and person-centered decision-making process.

Strengths and Limitations

One strength of this analysis is that the data were derived by trained and certified research staff, which increases the range of available fields and the accuracy of their ascertainment. The data also came from multiple centers and a diverse population, thereby increasing its generalizability. The method of model development incorporated best practices, such as consideration of non-linear effects and the use of internal-validation techniques. It should be noted that this model was derived from data collected nearly two decades ago. However, it was considered an imperative component of our approach to utilize the same data set and methodologic approach used to develop the prior VBAC prediction model. That model had been used and validated in multiple different settings, and the main purpose of this analysis was to determine whether a model with similar test characteristics could be produced after race and ethnicity were removed from consideration. Indeed, the newly-derived model is highly similar to the prior one, with almost identical input variables; the only substantive difference is the absence of race/ethnicity and the addition of chronic hypertension treated with medication, which is a condition that is associated with later obstetric complications (such as superimposed preeclampsia) associated with failed TOLAC.25 Moreover, despite the years that have passed, the overall chance that VBAC occurs once a TOLAC is undertaken has remained remarkably stable,20,26,27 and there is no evidence that the marginal associations of each variable with VBAC has changed over time, and thus there is reason to believe that this model continues to be relevant to modern obstetrical care.

Conclusions

Lastly, the removal of race and ethnicity from the model should serve to reinforce the importance of continually re-thinking past approaches to care and striving to achieve equity, without which there is no person-centeredness or quality. In that regard, it is important to note that there continue to be disparities in the cesarean rate among individuals who labor, with those who identify as Black or Hispanic having higher rates than those who identify as non-Hispanic White,28,29 and it is of crucial importance to target the social determinants that underlie those differences and eliminate the disparity and related morbidity that accrues consequent to it.

AJOG at a Glance:

- Why was the study conducted?

- A commonly-used tool to estimate the chance of vaginal birth among those undergoing trial of labor after one prior cesarean includes race and ethnicity as input variables.

- There are concerns that their inclusion reifies a biologic construct of race and ethnicity and may perpetuate health disparities

- What are the key findings?

- A prediction model that uses only information available at a first prenatal visit but does not including race and ethnicity was developed.

- The new model includes age, height, pre-pregnancy weight, occurrence of a prior vaginal birth, arrest indication for prior cesarean, and history of chronic hypertension.

- The new model had excellent calibration between predicted and empirical probabilities and, when applied to the overall analytic population, an AUC of 0.75 (95% CI: 0.74 – 0.77), which is similar to the AUC of the previous model (0.75) that included race/ethnicity.

- What does this study add to what is already known?

- This study provides a newly-developed tool for estimation of the probability of vaginal birth for those undergoing trial of labor after cesarean that can be used in shared decision making.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Francee Johnson, R.N., B.S.N., Elizabeth Thom, Ph.D., Michael W. Varner, M.D., and Catherine Y. Spong, M.D. for their respective roles in coordination between clinical research centers, protocol development, and oversight of the Cesarean Registry; and Yinglei Lai, PhD for his work on the original VBAC calculator analysis (revised in this manuscript).

The project described was supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [HD21410, HD21414, HD27860, HD27861, HD27869, HD27905, HD27915, HD27917, HD34116, HD34122, HD34136, HD34208, HD34210, HD40500, HD40485, HD40544, HD40545, HD40560, HD40512, and U01 HD36801] and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors report no conflict of interest

References

- 1.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Driscoll AK. Births: final data for 2018. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2018;68:1–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grobman WA, Lai Y, Landon MB, et al. The change in the rate of vaginal birth after caesarean section. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2011;25:37–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ACOG practice bulletin No. 205: vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133:e110–e127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox KJ. Counseling women with a previous cesarean birth: toward a shared decision-making partnership. J Midwifery Womens Health 2014;59:237–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grobman WA. Rates and prediction of successful vaginal birth after cesarean. Semin Perinatol. 2010;34:244–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metz TD, Stoddard GJ, Henry E, Jackson M, Holmgren C, Esplin S. Simple, validated vaginal birth after cesarean delivery prediction model for use at the time of admission. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122:571–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baranov A, Salvesen KÅ, Vikhareva O. Validation of prediction model for successful vaginal birth after Cesarean delivery based on sonographic assessment of hysterotomy scar. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2018;51:189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beninati MJ, Ramos SZ, Danilack VA, Has P, Savitz DA, Werner EF. Prediction Model for Vaginal Birth After Induction of Labor in Women With Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2020;136:402–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grobman WA, Lai Y, Landon MB, et al. Development of a nomogram for prediction of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2007;109:806–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costantine MM, Fox K, Byers BD, et al. Validation of the prediction model for success of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:1029–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yokoi A, Ishikawa K, Miyazaki K, Yoshida K, Furuhashi M, Tamakoshi K. Validation of the prediction model for success of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery in Japanese women. Int J Med Sci 2012;9:488–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaillet N, Bujold E, Dubé E, Grobman WA. Validation of a prediction model for vaginal birth after caesarean. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2013;35:119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mooney SS, Hiscock R, Clarke ID, Craig S. Estimating success of vaginal birth after caesarean section in a regional Australian population: Validation of a prediction model. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;59:66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haumonte JB, Raylet M, Christophe M, et al. French validation and adaptation of the Grobman nomogram for prediction of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod 2018;47:127–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Misgan E, Gedefaw A, Negash S, Asefa A. Validation of a Vaginal Birth after Cesarean Delivery Prediction Model in Teaching Hospitals of Addis Ababa University: A Cross-Sectional Study. Biomed Res Int 2020;2020:1540460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mone F, Harrity C, Mackie A, et al. Vaginal birth after caesarean section prediction models: a UK comparative observational study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2015;193:136–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vyas DA, Eisenstein LG, Jones DS. Hidden in Plain Sight - Reconsidering the Use of Race Correction in Clinical Algorithms. N Engl J Med 2020;383:874–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vyas DA, Jones DS, Meadows AR, Diouf K, Nour NM, Schantz-Dunn J. Challenging the use of race in the vaginal birth after cesarean section calculator. Women’s Health Issues 2019;29:201–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ioannidis JPA, Powe NR, Yancy C. Recalibrating the Use of Race in Medical Research. JAMA 2021. February 16;325(7):623–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landon MB, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes associated with a trial of labor after prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2581–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Calster B, McLernon DJ, van Smeden M, Wynants L, Steyerberg EW. Calibration: the Achilles heel of predictive analytics. BMC medicine. 2019;17(1):230–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaimal AJ, Grobman WA, Bryant A, et al. The association of patient preferences and attitudes with trial of labor after cesarean. J Perinatol 2019;39:1340–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McMahon MJ, Luther ER, Bowes WA Jr, Olshan AF. Comparison of a trial of labor with an elective second cesarean section. N Engl J Med 1996;335:689–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grobman WA, Lai Y, Landon MB, et al. Can a prediction model for vaginal birth after cesarean also predict the probability of morbidity related to a trial of labor? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;200:56. e1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mardy AH, Ananth CV, Grobman WA, Gyamfi-Bannerman C. A prediction model of vaginal birth after cesarean in the preterm period. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:513. e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macones GA, Cahill A, Pare E, et al. Obstetric outcomes in women with two prior cesarean deliveries: is vaginal birth after cesarean delivery a viable option? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;192:1223–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ha TK, Rao RR, Maykin MM, Mei JY, Havard AL, Gaw SL. Vaginal birth after cesarean: Does accuracy of predicted success change from prenatal intake to admission? Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2020;2:100094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bryant AS, Washington S, Kuppermann M, Cheng YW, Caughey AB. Quality and equality in obstetric care: racial and ethnic differences in caesarean section delivery rates. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2009;23:454–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yee LM, Costantine MM, Rice MM, et al. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Utilization of Labor Management Strategies Intended to Reduce Cesarean Delivery Rates. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:1285–1294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]