Abstract

This cohort study evaluates the short-term humoral response to a third dose of the SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 vaccine in patients undergoing acute systemic therapy for solid tumors.

Following massive global initiatives, the US Food and Drug Administration approved several SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, including the BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) mRNA vaccine. While manifestations of COVID-19 are heterogeneous, patients with solid tumors undergoing active therapy are at considerable risk for worse outcomes.1,2 Among these patients, humoral response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines has been reported in approximately 90%.3 Although high, this proportion is considerably lower than the 99% to 100% found in control groups.4 Among patients who are treated with chemotherapy, further reduced humoral responses have been described.3

The emergence of the Delta variant in June 2021 has increased both the number of confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infections and cases of severe illness.5 The variant’s heightened immune evasion and waning vaccine-elicited immunity in the population may explain high levels of viral transmission. Among adults 60 years and older who have received a vaccine booster as a third dose at least 5 months after second vaccination, the rate of confirmed infection was lower than in matched nonboosted adults by a factor of 11.3 as soon as 12 days after the booster shot, and the rate of confirmed infections was halved after only 4 to 6 days.5 Considering the lower immunogenic response to the BNT162b2 vaccine among patients with solid tumors, primarily those treated with chemotherapy, we evaluated the short-term (<30 days) humoral response to a third (booster) shot in this population.

Methods

Patients with solid tumors treated at the Hadassah Medical Center infusion center in Jerusalem, Israel were invited to participate in the study. The study was approved by the Hadassah Medical Center ethics committee, and participants gave informed consent prior to blood collection. Treatment was defined as chemotherapy, biologics, checkpoint inhibitors, or combinations. All enrolled patients had 2 previous BNT162b2 vaccines. Blood samples were collected at a median (range) of 13 (1-29) days after the BNT162b2 booster and analyzed for antibodies binding the spike protein, as in post–second vaccination (Liaison SARS-CoV-2 S1/S2 IgG [DiaSorin]).3 Before-vs-after antibody levels were compared using paired-sample t test, and multiple linear regression analysis was used to assess association of variables of interest with postbooster antibody levels. Analyses were performed using Prism, version 9 (GraphPad), and R, version 4.0.3 (R Foundation). A P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

From August 15 to September 5, 2021, a total of 37 patients underwent serologic testing after receiving a vaccine booster. The median (range) time interval between the booster and the second vaccine was 214 (172-229) days, and the median (range) interval between the second vaccine and the post–second vaccine antibody measurement was 86 (30-203) days.

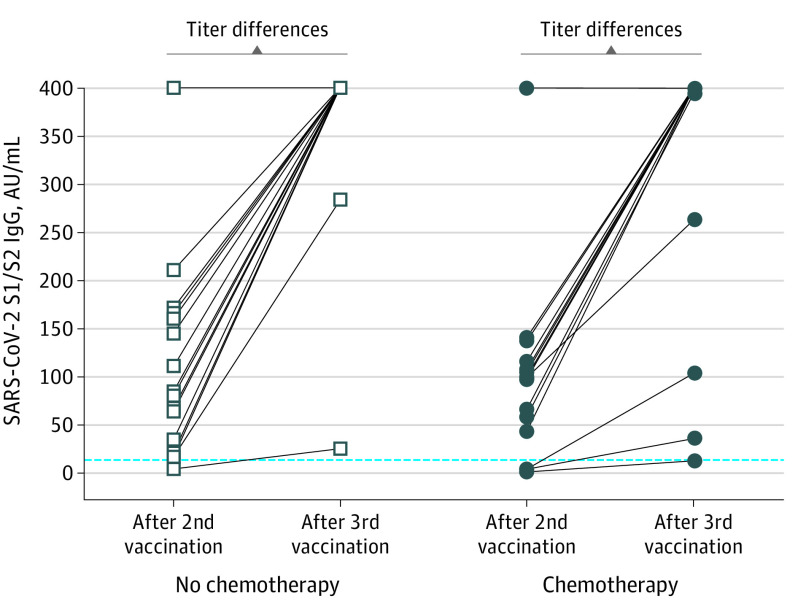

The median (range) age of patients was 67 (43-88) years. Eleven (30%) patients had nonmetastatic cancer, and 19 (51%) were being treated with chemotherapy. All but a single patient had a positive serologic test result (this patient was in their 40s without chronic illness and was undergoing adjuvant dose-dense doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel with trastuzumab and pertuzumab). Moreover, irrespective of the presence of chemotherapy in the treatment protocol, nearly all patients had excellent levels, and a statistically significant antibody step-up was noted, with patients who had shown a moderate or minimal response following the second dose included (Figure). Multiple linear regression disclosed that antibody levels post–second dose (0.497 units per 1 unit in log10 scale; P < .001) and older age (0.01 units in log10 scale per year; P = .03) were associated with higher antibody levels after the booster, while sex, chemotherapy status, and the interval between third dose and testing were insignificant (Table).

Figure. Serologic Response to a Third Dose of the SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 mRNA Vaccine in Patients With Cancer Undergoing Active Treatment.

Comparison between antibody levels after the second dose and the third booster dose of BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) in patients treated with chemotherapy and nonchemotherapy regimens. Measurements less than 12 AU/mL are considered negative, 12 to 19 AU/mL are equivocal, and greater than 19 are positive (dashed line). Levels above 60 AU/mL were shown to be protective. The upper antibody titer limit was capped at more than 400 AU/mL; thus, the titer differences may be higher than those recorded. The titer increment in both groups is statistically significant at P < .001.

Table. Results of Multiple Linear Regression With the Log10 Value of Antibody Levels After Booster Dose as the Dependent Variable and the Listed Independent Variables.

| Term | Estimate (SE) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.901 (0.357) | .02 |

| Chemotherapy, yes vs no | 0.005 (0.082) | .95 |

| Antibody level after 2nd vaccine dose per log10, AU/mLa | 0.497 (0.067) | <.001 |

| Age per y | 0.010 (0.005) | .03 |

| Sex, male vs female | 0.043 (0.078) | .58 |

| Interval between booster dosing per db | 0.001 (0.006) | .89 |

The antibody level after the second vaccine log10 transformed.

The interval in days between booster dosing and subsequent antibody measurement.

Discussion

Although limited by a small sample size, data in this cohort study suggest a generally positive and immediate antibody response to booster administration of the BNT162b2 vaccine among patients with cancer receiving active systemic therapy. These results align with other recent findings showing swift, substantial response in comparable booster-dosed populations (eg, solid organ transplant recipients).6

As for clinical ramifications, the present results support booster dosing of patients with cancer, including individuals being treated with chemotherapy. Accordingly, these results highlight the superiority of serial vaccinations over single dose among patients with solid cancers. Moreover, reduced rates of confirmed COVID-19 and severe illness among older adults in Israel following the BNT162b2 vaccine booster,5 combined with the immunogenic response found in this study, underscore the potential important role of booster doses in mitigating the risk of infection during the emergence of viral variants.

References

- 1.Brar G, Pinheiro LC, Shusterman M, et al. COVID-19 severity and outcomes in patients with cancer: a matched cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(33):3914-3924. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aschele C, Negru ME, Pastorino A, et al. Incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection among patients undergoing active antitumor treatment in Italy. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(2):304-306. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.6778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grinshpun A, Rottenberg Y, Ben-Dov IZ, Djian E, Wolf DG, Kadouri L. Serologic response to COVID-19 infection and/or vaccine in cancer patients on active treatment. ESMO Open. 2021;6(6):100283. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herishanu Y, Avivi I, Aharon A, et al. Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2021;137(23):3165-3173. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021011568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bar-On YM, Goldberg Y, Mandel M, et al. Protection of BNT162b2 vaccine booster against Covid-19 in Israel. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(15):1393-1400. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2114255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamar N, Abravanel F, Marion O, Couat C, Izopet J, Del Bello A. Three doses of an mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in solid-organ transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(7):661-662. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2108861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]