Abstract

Background:

The worldwide COVID-19 pandemic has significantly altered our life. Doctors more so than the general public because of their involvement in managing the COVID-infected individuals, some of them 24/7 end in burnout. Burnout in doctors can lead to reduced care of patients, increased medical errors, and poor health. Burnout among frontline health-care workers has become a major problem in this ongoing epidemic. On the other hand, doctors in preclinical department have a lack of interaction with patients, with not much nonclinical professional work to boot, find the profession less gratifying which perhaps increase their stress level.

Aim:

The aim was to study the prevalence of burnout and measure resilience in doctors in clinical and in preclinical departments.

Materials and Methods:

This observational, cross-sectional, comparative study was carried out in a tertiary care teaching hospital and COVID care center. By purposive sampling 60 preclinical and 60 clinical doctors in a tertiary health care center were included in the study. After obtaining the Institutional Ethics Committee approval and informed consent, the doctors were administered a self made socio-demographic questionnaire, the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory, and the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale. Doctors were given a self-made questionnaire, the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory, and the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale.

Results:

The prevalence of burnout was seen more in clinical doctors (55.47) and the resilience was observed more in preclinical doctors (88.9).

Discussion:

Resident doctors are a major force to combat COVID-19 as frontline health workers; hence, one can visualize burnout amongst them. On an individual basis, the work-related burnout was severely high in the clinical group owing to the workload which has been corresponding to a number of western studies. Nonclinical department doctors from pathology, community medicine, and microbiology did show burnout but showed a greater score in resilience. Psychological resilience has been identified as a component in preventing burnout.

Conclusion:

Therapy sessions can be used in clinical doctors facing burnout to build up their resilience.

Keywords: Burnout, clinical, COVID-19, doctors, preclinical, resilience

The practice of medicine is undoubtedly very meaningful, personally fulfilling, and rewarding. At the same time, it can also be demanding and stressful. Doctors are exposed to an extremely high level of stress during their profession and are particularly susceptible to experience burnout.[1,2] The high amount of stress in their day-to-day work puts them at a greater risk of experiencing depression, substance abuse, impairment in functioning, and even suicide. Burnout and intolerance in uncertainty have been linked to show low job satisfaction and low quality of patient care. The onset of burnout is often in the early postgraduation period. Burnout among doctors is a global phenomenon. By virtue of their profession, doctors are a vulnerable group for experiencing burnout. Burnout among doctors can result in poor patient care, increased medical mistakes, and low retention, as well as a worsening health outcome. Doctors in clinical department might also have to fulfill administrative duties for the effective functioning of workforce issues in addition.[3] On the other hand, doctors in preclinical department have a lack of interaction with patients and find the profession less gratifying which may increase their stress level.[4] The conclusive prevalence of burnout in doctors in a tertiary health-care center has not been evaluated and the prevalence of burnout in preclinical doctors. Surprisingly, very few studies have focused on burnout and resilience in preclinical department doctors. Given the evidence that burnout may adversely affect the quality of care and negatively affect physician health, with this study, we aim to have a better understanding of the prevalence of burnout among the doctors in a tertiary health-care center.

The worldwide pandemic of coronavirus illness 2019 (COVID-19) has radically altered how we live and work. Burnout among frontline health-care workers has been a major worry as the pandemic continues. Now, it is difficult to think about burnout without considering the impact of the COVID-19 epidemic. With over 1.3 billion people, India is a vast country in terms of population. It has a wide range of demographic characteristics. Behind the United States, India is the second most Covid-19-affected country by the total number of infected persons as of September 10, 2020. As a result, the COVID-19 pandemic scenario in India allows us to double-check current findings. On April 26, India had the world's largest daily tally of new SARS-CoV-2 infections, 360,960, bringing the country's pandemic total to 16 million cases, second only to the United States, and more than 200,000 fatalities. Then, there is India's health-care system, which was already in poor shape before to the epidemic and is now completely overloaded.[5]

Frontline workers, on the other hand, were shown to have a reduced rate of burnout in one research. The possibility is that by directly addressing COVID-19, frontline participants felt more in control of their position; control in the workplace is believed to be a significant motivator of engagement and crucial for preventing burnout. Those working on their regular wards may have felt less in control of new rules and procedures implemented to keep staff and patients safe, and instead of confronting COVID-19 straight on, these employees may have felt that the virus might strike at any time, regardless of those measures.[6] The crisis may increase people's feeling of purpose, changing our personal and technical interactions with patients. Alternatively, the stress and strain of daily clinical labor during the epidemic, as well as the death of colleagues and loved ones, may lead to disillusionment or despair among many clinicians. It will be difficult to predict the pandemic's long-term impact on medical burnout until it is finished.[7] In view of the paucity of work in this area, the project was undertaken to study the prevalence of burnout and measure resilience in doctors in clinical and in preclinical departments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

It is an observational, cross-sectional, comparative study taken place in a tertiary health-care center. A sample size of 120 participants was arrived at using sample size calculation formula for cross-sectional studies, n = Z2(p)(1 − p)/c2, where “n” is the required sample size, “Z” is standard score corresponding to 95% confidence level (0.05), “p” is the probability that a doctor will have burnout (0.1). The study was taken up after obtaining the clearance from the Institutional Ethics Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants enrolled for the study. Sixty clinical branch doctors and 60 preclinical branch doctors at a random after preevaluation of the inclusion criteria of doctors who are caring for in-patients (first group), doctors without in-patients (second group, and doctors willing to participate in the study were given the questionnaire consisting of sociodemographic details, field of specialty, the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory, and the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale. Doctors diagnosed with any diagnosed illness formed the exclusion criteria of the study.

All the doctors in the inclusion criteria, who have given consent, were evaluated using the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory and the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale, and their scores were evaluated. All data were compiled on the master chart on Microsoft Excel sheet.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed utilizing the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 17.0 (SPSS, IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) with a significance threshold of 0.05. The evaluations of burnout were dichotomized to investigate the predictability of burnout correlates. Frequency data were compared using Chi-square test, continuous data using the Student's t-test, and ordinal data by Mann–Whitney test. A multiple regression analysis was run to determine the predictors of work burnout from age, sex, specialty, personal burnout, client burnout, and resilience.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic-related characteristics of participants

The respondents' age was from between 24 and 34 years. The mean (standard deviation [SD]) age of the clinical group was 27.10 (1.85) years. Age ranged from 25 to 34 years. In nonclinical group, mean (SD) of age was 26.77 (1.65) years. The two groups were comparable in age (t = −1.042; df = 118; P = 0.299, not significant). In nonclinical group, there were 32 females and 28 males, while in clinical group, there were 34 males and 26 females (Chi-square = 1.20; P = 0.273; not significant) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and scores on Copenhagen Burnout Inventory and CD risk of doctors in clinical and nonclinical specialties during COVID-19 pandemic

| Characteristic | Clinical | Nonclinical | Clinical | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 27.10 (1.85) | 26.77 (1.65) | t=−1.042; df=118 | 0.299 |

| Range | 25-34 | 24-32 | - | - |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 34 | 28 | χ2=1.20 | 0.273 |

| Female | 26 | 32 | ||

| Personal | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 58.72 (7.96) | 41.97 (3.78) | MWU=140.00 | 0.000 |

| Range | 37.50-83.30 | 37.50-58.30 | ||

| Work | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 64.27 (10.04) | 35.8417 (3.79) | MWU=0.000 | 0.000 |

| Range | 46.4-92.80 | 32.1-42.8 | ||

| Client | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 51.70 (9.09) | 34.34 (8.17) | MWU=225.00 | 0.000 |

| Range | 33.30-79.10 | 20.80-58.30 | ||

| Resilience | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 75.18 (11.95) | 89.48 (4.67) | MWU=455.00 | 0.000 |

| Range | 50.00-94.00 | 78.00-98.00 |

SD – Standard deviation; MWU – Mann-Whitney U-test

Out of the 60 clinical doctors, 3 held super-specialty degree, while the rest were perusing their postgraduation course with once year of residency completed. In the nonclinical group, all the respondents were perusing their postgraduation courses.

Prevalence of burnout

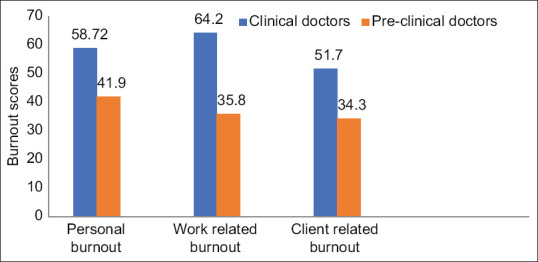

The burnout was assessed under “personal related burnout,” “work related burnout,” and “client related burnout” as per the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory. Mean (SD) of personal-, work-, and client-related burnout in doctors of clinical department was 58.72 (7.96), 64.72 (10.04), and 51.07 (9.09), respectively. The mean (SD) of personal-, work-, and client-related burnout in doctors of preclinical departments was 41.97 (3.78), 35.8 (3.79), and 34.34 (8.17), respectively [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Mean values of burnout

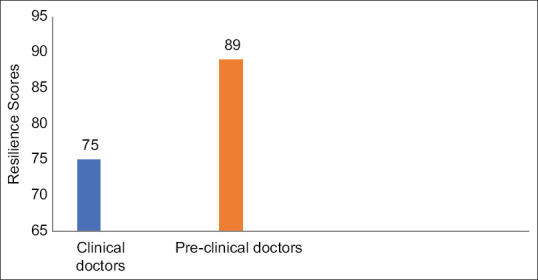

Prevalence of resilience

As per the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale, the mean (SD) of resilience in clinical doctors is 75.18 (11.95) and that of preclinical doctors is 89.48 (4.67) [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Mean value of resilience

Predictors of work burnout

A multiple regression was run to predict work burnout scores from age, sex, specialty, personal burnout, client burnout, and resilience. These variables statistically significantly predicted CDRS scores, F (6, 113) =57.767, P < 0.000, R2 = 0.754. Only specialty and resilience scores added were statistically significant to the prediction, P < 0.05 [Tables 2-4].

Table 2.

Regression analysis to determine the predictors of work burnout: Model summaryb

| Model | R | R 2 | Adjusted R2 | SE of the estimate | Durbin-Watson |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.868a | 0.754 | 0.741 | 55.24111 | 1.514 |

aPredictors: Constant, CDRS, sex, age, client burnout, pers burnout, specialty, bDependent variable: Work burnout. SE – Standard error; CDRS – Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale

Table 4.

Regression analysis to determine the predictors of work burnout: Coefficientsa

| Model 1 | Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients (β) | t | Significant | 95.0% CI for B (lower bound-upper bound) | Collinearity statistics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| B | SE | Tolerance | VIF | |||||

| Constant | 606.732 | 97.881 | 6.199 | 0.000 | 412.812-800.652 | |||

| Age | −3.936 | 3.001 | −0.064 | −1.312 | 0.192 | −9.881-2.009 | 0.927 | 1.078 |

| Sex | 0.827 | 10.239 | 0.004 | 0.081 | 0.936 | −19.457-21.111 | 0.973 | 1.028 |

| Speciality | −155.772 | 23.450 | −0.720 | −6.643 | 0.000 | −202.231-−109.313 | 0.185 | 5.406 |

| Pers burnout | 0.107 | 0.139 | 0.062 | 0.767 | 0.444 | −0.169-0.382 | 0.338 | 2.960 |

| Client burnout | 0.005 | 0.098 | 0.003 | 0.047 | 0.962 | −0.190-0.200 | 0.470 | 2.128 |

| CDRS | −1.375 | 0.581 | −0.146 | −2.369 | 0.020 | −2.526-−0.225 | 0.571 | 1.751 |

aDependent variable: Work burnout. SE – Standard error; CI – Confidence interval; VIF – Variance inflation factor; CDRS – Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale

Table 3.

Regression analysis to determine the predictors of work burnout: ANOVAa

| Model 1 | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | Signficance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 1057679.343 | 6 | 176279.890 | 57.767 | 0.000b |

| Residual | 344828.524 | 113 | 3051.580 | ||

| Total | 1402507.867 | 119 |

aDependent variable: Work burnout, bPredictors: Constant, CDRS, sex, age, client burnout, pers burnout, specialty. CDRS – Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale

DISCUSSION

This study was done with an aim to find the prevalence of burnout in doctors, to measure the resilience in doctors, and to compare the burnout and resilience in clinical doctors and in preclinical doctors. The findings from this study draw attention to the recognition that resident doctors form the major nucleus of health-care delivery in the tertiary health-care system.

An earlier study found a higher incidence of burnout among younger resident doctors in the United States, while another study found no connection between age and burnout among practicing physicians and family medicine residents.[8,9,10] Our study findings are consistent with these studies, since age did not have an effect on our results, as reflected in Table 1.

Estimate of burnout in doctors often yields high figures and varies between countries, across time, specialties, or sector of work, i.e., public/private, or rural/urban. This variation is understandable and expected because burnout is related to stressors arising from work environment and work environment is influenced by these variables.[8,11] Hence, the results cannot be generalized. Here, the doctors belonged to a tertiary center of an urban area in Pune, Maharashtra. The worse outbreak of the COVID19 in India was observed in Maharashtra, with Pune being the second worst-hit city of India.

A study from rural British Columbia reported that 80% of physicians suffered from moderate-to severe emotional exhaustion, 61% suffered from moderate-to-severe depersonalization, and 44% had moderate-to-low feelings of personal accomplishment.[12] A more recent study of US physicians found that 46% of the respondents had at least one symptom of burnout. European General Practice (GP) Research Network Burnout Study Group, on the other hand, found that, while 12% of participants suffered from burnout in all three dimensions,[8] this result has been consistent with our findings [Figure 1].

One survey found that a lower prevalence of burnout is present in GP registrars than other recent surveys of the Australian junior doctor population. They found no relationship between a registrar's duration of GP experience and burnout. Georga[13] also found that burnout in GP registrars is also strongly linked with general intolerance of uncertainty. Resilience was also lower than might be expected. Resilience was linked to high compassion satisfaction, low burnout, and a higher tolerance of both general and clinical uncertainty Some studies have reported a positive correlation between high levels of burnout and high levels of job satisfaction. Others have found that low levels of job satisfaction may be associated with high levels of burnout.[4,6,14] Our study found a greater score in resilience in preclinical doctors than the clinical doctors [Figure 2] showing a positive correlation between high levels of burnout to lower resilience.

Previous studies have found that emotional exhaustion has the strongest association with stressors among doctors. Emotional exhaustion is an early symptom of burnout, which leads to depersonalization and higher burnout scores.[8,12] They also reported having greater job satisfaction, and thus lower burnout levels, may lead to greater perseverance and higher grit levels through positive reinforcement of burnout, and yet, there is some evidence to suggest the relationship between specific dimensions of burnout and job satisfaction may change over time.[11,15]

In a research conducted in Japan, it was shown that 50% of frontline HCWs who provided direct care to COVID-19 patients or person under investigation (PUI) reported burnout, a considerably greater rate than those who did not provide direct care to COVID-19 patients or PUI.[16] Being consistent with our study, the paraclinical group reported less burnout.

In an Indian study, personal burnout was reported by 44.6%, work-related burnout by just 26.9%, and pandemic-related burnout by more over half of the respondents. Personal- and work-related burnout was greater in younger responders (21–30 years). Females were considerably more likely than males to experience personal- and work-related burnout.[17] In this study, there was no significance found in the gender. Men and women faced burnout equally.

According to a study in Romania, medical residents had an average burnout rate of 76% two months following the emergence of pandemic, which is higher than studies done prior to the pandemic. The threat posed by SARS CoV 2 is a major stressor for doctors, as seen by the high frequency of burnout syndrome among medical residents across the world. The findings are a matter of concern because the affected group consists of resident doctors under the age of 35, who, at least theoretically, should be more adaptable to the new situation represented by this pandemic than older practitioners. This study revealed that the resident doctors being in the frontline, serve as a bridge between patient and the older practitioners. The resident doctors had higher prevalence of burnout since they did not get any time to adapt to the new reality and had to struggle to keep up with the constantly changing protocols of treatment.[18,19] The finding of much higher work related burnout in the clinical group corresponds to the above studies. Resident doctors from nonclinical departments like pathology, community medicine and microbiology, also did show some burnout but showed a greater score in resilience which has a link with the high compassion satisfaction. Psychological resilience has been identified as a component in preventing burnout. Individuals' psychological resilience is described as their ability to adapt and respond to adversity.[20,21] Resilience may be a potential mediator between depression and burnout, according to a recent Portuguese study, with strong resilience being protective against burnout.[19,22,23] Our study points in that direction. However, we did not come across any study estimating the burnout and resilience in doctors of the nonclinical departments.

Limitations of the study

The study's primary drawback was its cross-sectional design, which prevented the determination of the temporal order in the relationships between burnout and work-related stresses. The limited sample size and from a single tertiary hospital could add to the bias. A drawback of this study was the possibility of memory bias in the self-reported measures utilized which could not be avoided due to the prevailing pandemic restrictions and norms.

Future implications

The present study found that burnout and its work related consequences are common in doctors. The findings of this study will help plan therapeutic programs and research on ways to reduce stress in the workplace, especially for resident doctors. Furthermore, prospective, controlled studies are needed to investigate the risk factors for burnout and other mental health disorders among clinical doctors, as well as the effects of treatment. Easily accessible and effective mental health cafes could be established to provide psychological help to the doctors in need.

CONCLUSION

Burnout is quite common among clinical doctors, according to the research. The three aspects of burnout were linked to variables such as an excessive workload and emotional discomfort. The stigma connected to doctors who admit to mental health issues, as well as the need for mental health promotion in general, should be discussed openly. Regular conduction of feedbacks from the doctors, aiding them relaxation techniques or any forms of stress-relieving strategies, could bring down the burnout incidence rate. Some measures such as reducing workload, some mitigating interventions, namely mindfulness, and counseling those at risk of burnout have been proposed as measures to address the widespread burnout.[24,25] Job satisfaction among the preclinical doctors is to be emphasized. Addressing them is not just the need of the hour but professional essentiality of current era.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kumar S. Burnout and doctors: Prevalence, prevention and intervention. Healthcare (Basel) 2016;4:E37. doi: 10.3390/healthcare4030037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Srivastava K, Chaudhry S, Sowmya AV, Prakash J. Mental health aspects of pandemics with special reference to COVID-19. Ind Psychiatry J. 2020;29:1–8. doi: 10.4103/ipj.ipj_64_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saini RK, Chaudhary S, Raju M, Srivastava K. Caring for the COVID warriors: A healthcare's perspective in the challenging times. Ind Psychiatry J. 2020;29:355–6. doi: 10.4103/ipj.ipj_167_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCain RS, McKinley N, Dempster M, Campbell J, Kirk SJ. A study of the relationship between resilience, burnout and coping strategies in doctors. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2018;94:43–7. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2016-134683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thiagarajan K. Why is India having a covid-19 surge? BMJ. 2021;373:n1124. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaudhury S, Pooja V, Thakur M, Saldanha D. Covid 19 pandemic anxiety and its management. Acta Sci Neurol. 2020;3:39–41. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Launer J. Burnout in the age of COVID-19. Postgrad Med J. 2020;96:367–8. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-137980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, Dyrbye LN, Sotile W, Satele D, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1377–85. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown PA, Slater M, Lofters A. Personality and burnout among primary care physicians: An international study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019;12:169–77. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S195633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dyrbye LN, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, Herrin J, Wittlin NM, Yeazel M, et al. Association of clinical specialty with symptoms of burnout and career choice regret among US resident physicians. JAMA. 2018;320:1114–30. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.12615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halliday L, Walker A, Vig S, Hines J, Brecknell J. Grit and burnout in UK doctors: A cross-sectional study across specialties and stages of training. Postgrad Med J. 2017;93:389–94. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woodside JR, Miller MN, Floyd MR, McGowen KR, Pfortmiller DT. Observations on burnout in family medicine and psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2008;32:13–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.32.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooke GP, Doust JA, Steele MC. A survey of resilience, burnout, and tolerance of uncertainty in Australian general practice registrars. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kristensen TS, Borritz M, Villadsen E, Christensen KB. The Copenhagen burnout inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work Stress. 2005;19:192–207. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mache S. Coping with job stress by hospital doctors: A comparative study. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2012;162:440–7. doi: 10.1007/s10354-012-0144-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishimura Y, Miyoshi T, Hagiya H, Kosaki Y, Otsuka F. Burnout of healthcare workers amid the COVID-19 pandemic: A Japanese cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:2434. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khasne RW, Dhakulkar BS, Mahajan HC, Kulkarni AP. Burnout among healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic in India: Results of a questionnaire-based survey. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2020;24:664–71. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dimitriu MC, Pantea-Stoian A, Smaranda AC, Nica AA, Carap AC, Constantin VD, et al. Burnout syndrome in Romanian medical residents in time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Hypotheses. 2020;144:109972. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mason S, O'Keeffe C, Carter A, Stride C. A longitudinal study of well-being, confidence and competence in junior doctors and the impact of emergency medicine placements. Emerg Med J. 2016;33:91–8. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2014-204514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) Depress Anxiety. 2003;18:76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.West CP, Tan AD, Habermann TM, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Association of resident fatigue and distress with perceived medical errors. JAMA. 2009;302:1294–300. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serrão C, Duarte I, Castro L, Teixeira A. Burnout and depression in Portuguese healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic-the mediating role of psychological resilience. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:E636. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Connor P, Lydon S, O'Dowd E, Byrne D. The relationship between psychological resilience and burnout in Irish doctors. Ir J Med Sci. 2021;190:1219–24. doi: 10.1007/s11845-020-02424-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Correia I, Almeida AE. Organizational justice, professional identification, empathy, and meaningful work during COVID-19 pandemic: Are they burnout protectors in physicians and nurses? Front Psychol. 2020;11:566139. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.566139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chakraborty R, Chatterjee A, Chaudhury S. Internal predictors of burnout in psychiatric nurses: An Indian study. Ind Psychiatry J. 2012;21:119–24. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.119604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]