Summary

Dietary consumption of ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), present in fish oils, is known to improve vascular response; however, their molecular targets remain largely unknown. Activation of the TRPV4 channel has been implicated in endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation. Here, we studied the contribution of ω-3 PUFAs to TRPV4 function by precisely manipulating the fatty acid content in Caenorhabditis elegans. By genetically depriving the worms of PUFAs, we determined that the metabolism of ω-3 fatty acids is required for TRPV4 activity. Functional, lipid metabolome, and biophysical analyses demonstrated that ω-3 PUFAs enhance TRPV4 function in human endothelial cells and support the hypothesis that lipid metabolism and membrane remodeling regulate cell reactivity. We propose a model whereby the eicosanoid’s epoxide group location increases membrane fluidity and influences endothelial cell response by increasing TRPV4 channels activity. ω-3 PUFA-like molecules might be viable antihypertensive agents for targeting TRPV4 to reduce systemic blood pressure.

Introduction

Since humans lack the ability to synthesize the precursors of long polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), they are an integral part of our diet. Consumption of foods rich in PUFAs has been linked with a wide range of health benefits, including improved cognitive function, metabolism, and longevity (Swanson et al., 2012). Omega (ω)-3 PUFAs found in fish and enriched food products are suggested to prevent vascular dysfunction by decreasing vasoconstrictors (Wiest et al., 2016). In the cardiovascular system, ω-3 PUFAs, such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), have been shown to have anti-arrhythmic, antithrombotic, and anti-inflammatory properties (Endo and Arita, 2016). A consensus view has yet to emerge regarding the targets and the precise mechanism(s) by which ω-3 PUFAs exert their physiological roles.

PUFAs and their metabolites can modulate ion channels and other receptors at the plasma membrane directly by binding to the protein or indirectly by changing the physical properties of the bilayer. For instance, voltage- and ligand-gated channels are directly modulated by fatty acids (Basak et al., 2017; Tian et al., 2016). On the other hand, PUFA-containing phospholipids have been shown to modulate the mechanoreceptor and phototransduction channel complexes in C. elegans (Vasquez et al., 2014) and D. melanogaster (Randall et al., 2015), respectively, by altering the mechanical properties of the membrane. Biophysical evidence collected from synthetic and natural membranes support the hypothesis that PUFAs differentially influence the membrane physical properties (Mason et al., 2016). ω-6 PUFAs, such as arachidonic acid (AA) and its metabolites epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs), have been shown to activate the transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 channel (TRPV4) downstream of cell swelling (Vriens et al., 2004; Watanabe et al., 2003). TRPV4 is a polymodal ion channel also activated by temperature changes (Watanabe et al., 2002b), mechanical stimuli (Liedtke et al., 2000; Servin-Vences et al., 2017; Strotmann et al., 2000), and chemical ligands (Thorneloe et al., 2008; Watanabe et al., 2002a). TRPV4 plays a role in reducing systemic blood pressure by integrating hemodynamic forces and chemical cues in endothelial and smooth muscle cells (Peixoto-Neves et al., 2015; Sonkusare et al., 2012). Activation of TRPV4 promotes vasodilation through the increase of intracellular Ca2+, nitric oxide release, and subsequent smooth muscle cell hyperpolarization (Earley et al., 2005). To better understand the molecular mechanisms by which TRPV4 modulates vascular reactivity, it is important to identify the metabolic pathways that modulate its function.

Previous studies of the mechanisms by which ω-6 AA metabolites modulate TRPV4 function used inhibitors of cytochrome P450, whose substrates are ω-6 and ω-3 PUFAs; hence, their individual contributions (specifically for ω-3 PUFAs) to channel function have been difficult to distinguish (Fleming, 2014). Therefore, we hypothesized that ω-3 PUFAs modulate TRPV4 function. Although rodents have been a good model for studying the role of TRPV4 in vasodilation (Earley et al., 2009), they are less amicable when determining the precise contribution of individual fatty acids to channel function. A more systematic analysis of the mechanisms and pathways by which individual PUFAs and/or their metabolites modulate TRPV4 activity requires the evaluation of channel function in a system that allows for precise manipulation of the membrane environment. To study the effect of ω-3 PUFAs in TRPV4 function, we used C. elegans –an animal whose membranes can be genetically deprived of PUFAs. It has been shown that C. elegans is a powerful tool for distinguishing the role of PUFAs in whole organisms (Watts, 2016). The advantage of studying lipid signaling in worms is that, unlike mammals, they have all the enzymes required for PUFAs syntheses (Wallis et al., 2002) and a wide collection of PUFA-deficient mutants (Watts and Browse, 2002); these attributes allow for accurate membrane remodeling. Importantly, a mammalian TRPV4 channel was functionally expressed in the worm’s ASH polymodal sensory neurons (Liedtke et al., 2003); activation of these neurons elicits worms’ aversive responses (Bargmann, 2006). Based on this knowledge, we sought to gain insight into how PUFAs and their eicosanoid derivatives modulate TRPV4 activity.

Here, using in vivo screening in a transgenic worm expressing rat TRPV4, we found that EPA and its eicosanoid derivative epoxyeicosatetraenoic acid (17,18-EEQ) are required for channel function. We leveraged genetic dissection, knockdown assays, and diet supplementation to establish that membranes with reduced levels of PUFAs- and eicosanoids negatively regulate TRPV4 activity. Combining electrophysiology, Ca2+ imaging, and lipidomics, we demonstrate that in human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC), EPA increases the number of TRPV4 channels available for activation and decreases Ca2+-dependent desensitization in response to chemical and physical stimuli. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) experiments revealed that ω-3 PUFAs increase membrane fluidity and decrease bending stiffness. Hence, we proposed a model whereby ω-3 fatty acid metabolism and membrane remodeling enhance TRPV4 function in sensory neurons (worms) and endothelial cells (humans).

Results

Chemically Mediated Withdrawal Responses in Mammalian TRPV4-Expressing Worms

We implemented a chemical strategy to study the contribution of PUFAs to TRPV4 function in C. elegans. We used worms expressing rat TRPV4 (not encoded in the C. elegans genome) in ASH sensory neurons to couple channel activation with a robust and easily observable behavior (i.e., escape) (Liedtke et al., 2003). For behavioral assays, we used GSK1016790A (GSK101), a potent TRPV4 agonist that activates TRPV4-expressing HEK293 cells, as determined by whole-cell patch clamp recording and live-cell calcium imaging [Figure S1A-B and elsewhere (Thorneloe et al., 2008)]. We chose to use a specific and robust activator to provide unambiguous evidence of channel regulation by fatty acids. The behavioral trials were performed by placing drops (Hart, 2006) of different GSK101 concentrations in front of moving worms (Figure 1A); trials that elicited reversals of motion were scored as withdrawal responses. We found that GSK101 elicited robust withdrawal responses in a dose-dependent manner in TRPV4-expressing worms but not in wild type (Figure 1B). We considered withdrawal responses over 20% (red dotted line; Figure 1B) as evidence of evoked-escape behavior. Next, we tested the specificity of the GSK101-mediated behavior by supplementing the worms’ diet with the TRPV4 antagonist HC067047 (Figure S1C). Importantly, worms’ withdrawal responses were abolished (<20%) in the presence of HC067047 (Figure 1C), indicating that TRPV4 mediates the aversive behavior in response to GSK101. Withdrawal responses were also elicited by a different TRPV4 agonist, 4α-phorbol (Watanabe et al., 2002a), in transgenic but not wild-type worms (~55%; Figure 1D), supporting the chemical-mediated stimulation as a readout of TRPV4 function.

Figure 1.

GSK101 elicits withdrawal responses in rat TRPV4-expressing worms. (A) Schematic representation of the withdrawal responses after addition of GSK101 drop in front of freely moving worms. (B) GSK101 dose-response profile for wild-type (WT [N2]) and TRPV4-expressing worms. (C) Inhibition of GSK101-mediated withdrawal responses in TRPV4 worms by HC067047 (2 µM). (D) Withdrawal responses elicited by 4α-Phorbol in WT and TRPV4 worms. (E) Withdrawal responses elicited by 1 M glycerol and nose touch in WT, osm9, and TRPV4; osm9 strains. Bars are mean ± SEM, the number of worms tested during 3 assays sessions is indicated inside the bars. The asterisks indicate values significantly different from control. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, and *p < 0.05. See also Figure S1.

As shown by Liedtke et al. and in Figure 1E, rat TRPV4 expressed in ASH neurons of osm-9 worms (e.g., mutants insensitive to osmotic and mechanical stimuli) restored the withdrawal responses to 1 M glycerol and nose touch stimuli. Although TRPV4 in C. elegans and mice responds to hyperosmolarity (Liedtke and Friedman, 2003; Liedtke et al., 2003), in cultured cells (e.g., transfected HEK293 and endothelial cells) it responds to hyposmotic challenges (Vriens et al., 2004). We speculate that these discrepancies might be due to the presence/lack of extracellular components that are inherent to in vivo and ex vivo approaches. It is also noteworthy that worms rely on the mechanoreceptor DEG-1 and the downstream OSM-9 channels for ASH-mediated mechanical responses (Colbert et al., 1997; Geffeney et al., 2011). Taken together, our results support the chemical strategy for specifically determining the contribution of fatty acids to TRPV4 function in vivo.

PUFAs Are Required for TRPV4 Function

C. elegans synthesizes long (20-carbon chain) PUFAs using a series of fatty acid desaturase (FAT) and elongase (ELO) enzymes; FAT-deficient mutants grow into normal adults with mild phenotypes (Watts et al., 2003). The enzyme FAT-3 is essential for the generation of ω-3 and ω-6 PUFAs (Figure 2A). To determine the role of PUFAs and their metabolites in TRPV4 function, we crossed TRPV4 worms with a strain lacking the function of the FAT-3 enzyme. Remarkably, TRPV4; fat-3 worms were found to be completely insensitive to GSK101 (Figure 2B, red bar). Furthermore, 4α-phorbol was also unable to elicit withdrawal responses in worms of this genetic background (Figure 2C). Because worms can efficiently incorporate fatty acids through their diet (Watts and Browse, 2002), we asked whether supplementation with a common dietary PUFA (e.g., ω-6 AA) would restore the withdrawal response of TRPV4; fat-3 worms. Indeed, PUFA supplementation was sufficient to restore the withdrawal response of TRPV4; fat-3 worms compared to control diet ones (Figure 2B). Our results indicate that long-chain PUFAs synthesized downstream of FAT-3 are required for TRPV4 function in vivo. We next assessed the behavioral responses of TRPV4 worms in the absence of FAT-4 enzyme (TRPV4; fat-4). Unlike fat-3 worms, fat-4 mutants lack only the desaturase enzyme responsible for the synthesis of ω-6 AA and EPA (Figure 2A). TRPV4; fat-4 worms also displayed significantly impaired withdrawal responses (~40%; Figures 2D and S2A). This finding support that the accumulation of upstream fatty acid precursors in fat-4 worms, such as ω-3 AA (Kahn-Kirby et al., 2004), partially restores TRPV4 function (Figure 2A). Considering these findings, we conclude that long PUFAs are required for TRPV4 chemically mediated responses in worms. To test whether PUFAs are required for other TRPV4 gating modalities (e.g., osmotic and mechanical), we generated the TRPV4; osm-9fat-3 strain. Our results showed that in the absence of PUFAs, this TRPV4 strain failed to show withdrawal responses when challenged with 1 M glycerol or nose touch (Figure 2E). Even though we observed a mechanical defect in TRPV4 worms lacking PUFAs, we were unable to distinguish the contribution of DEG-1. Nonetheless, these results suggest that PUFAs affect more than one TRPV4 gating modality.

Figure 2.

PUFAs are required for TRPV4 function in C. elegans. (A) Fatty acid desaturase (FAT) and elongase enzymes (ELO) synthesize long PUFAs, and cytochrome P450 (CYPs) generates eicosanoid derivatives, adapted from (Watts, 2009). LA, linolenic acid; γLA, γ-linolenic acid; DγLA, dihomo-linolenic acid; ω-6 AA, arachidonic acid; EET, epoxy-eicosatrienoic acid; ALA, α-linolenic acid; STA, stearidonic acid; ω-3 AA; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; EEQ, 17’18’-epoxy eicosatetraenoic acid. (B) Withdrawal responses elicited by GSK101 in WT, TRPV4, TRPV4; fat-3, and TRPV4; fat-3 worms supplemented with PUFAs. (C) Withdrawal responses elicited by 4α-Phorbol in WT, TRPV4, and TRPV4; fat-3 worms. (D) Withdrawal responses elicited by GSK101 in TRPV4 and TRPV4; fat-4 worms. (E) Withdrawal responses elicited by 1 M glycerol and nose touch in TRPV4; osm9 and TRPV4; osm9fat-3 strains. (F) Representative micrographs of TRPV4::GFP and TRPV4::GFP; fat-3 ASH neurons. (G) Box plots show the mean, median, and the 75th to 25th percentiles of the fluorescence intensity analysis from images in (F). The number of neurons imaged during 2 sessions is indicated below the boxes. (H) Schematic representation of the phospholipid synthesis. (I) GSK101 withdrawal responses after knocking down the expression of mboa-6 in TRPV4 worms. Bars are mean ± SEM, the number of worms tested during 3 assays sessions is indicated inside the bars. The asterisks indicate values significantly different from control. ***p < 0.001 and ns: no significant. See also Figure S2.

Reduced withdrawal behavior of TRPV4; fat-3 worms could arise from general defects of ASH neurons (e.g., excitability and/or morphology) or direct effects on TRPV4 channel localization and/or function. To distinguish between these possibilities, we challenged rat TRPV1 (a channel whose activation is independent of PUFAs) transgenic worms with capsaicin in the genetic background of the fat-3 mutant. Capsaicin elicits aversive behavior in worms expressing rat TRPV1 in the ASH neurons, but not in wild-type worms (Tobin et al., 2002). As expected, the withdrawal responses of the TRPV1-expressing worms were indistinguishable regardless of the PUFA content as observed in Figure S2B and elsewhere (Kahn-Kirby et al., 2004). Hence, PUFAs specifically affect TRPV4 activity rather than the overall function of the ASH neurons. Imaging experiments using TRPV4::GFP and TRPV4::GFP; fat-3 worms (Figures 2F-G) revealed no significant differences in the mean fluorescence intensity and ASH neuron morphology that could account for the lack of behavioral response of TRPV4; fat-3 mutants. Therefore, impaired TRPV4 function in the fat-3 genetic background is not due to ASH morphology defects or channel trafficking. Altogether, these findings demonstrate that in worms, TRPV4 channels are not active in an environment devoid of PUFAs.

PUFA-Containing Phospholipids Are Required for TRPV4 Channel Function

Given that dietary PUFAs can display biological activity when incorporated into membrane phospholipids and/or when present as free fatty acids, we sought to determine whether PUFA-containing phospholipids are required for TRPV4 activity in vivo. C. elegans expresses a conserved lysophospholipid acyltransferase enzyme required for the incorporation of PUFAs into phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, and phosphatidylserine from lysophospholipids (MBOA-6; Figure 2H). Since mboa-6-null worms display embryonic lethality (Matsuda et al., 2008), we knocked down mboa-6 via RNAi in TRPV4 worms. Depletion of MBOA-6 resulted in a significant decrease in GSK101 withdrawal responses compared to those seen in control worms (Figures 2I and S2C). To determine the changes in fatty acid composition in phospholipids after treating worms with mboa-6 RNAi, we used liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). We found: 1) increased levels of free ω-6 AA and EPA (Figure S2D, top), which are consistent with the idea that these PUFAs are not efficiently incorporated into phospholipids; and 2) increased levels of esterified fatty acids containing 0 and 1 unsaturation (Figure S2D, bottom), supporting that mboa-6 treatment disrupted the balance between phospholipids containing saturated (stearic acid, 18:0) and monounsaturated (oleic acid, 18:1n-9) fatty acids vs. polyunsaturated ones (ω-6 AA and EPA). Taken together, our results demonstrate that PUFAs contained in phospholipids are required for TRPV4 activity.

in vivo Screen Reveals that ω-3 Fatty Acid Metabolites Are Required for TRPV4 Function

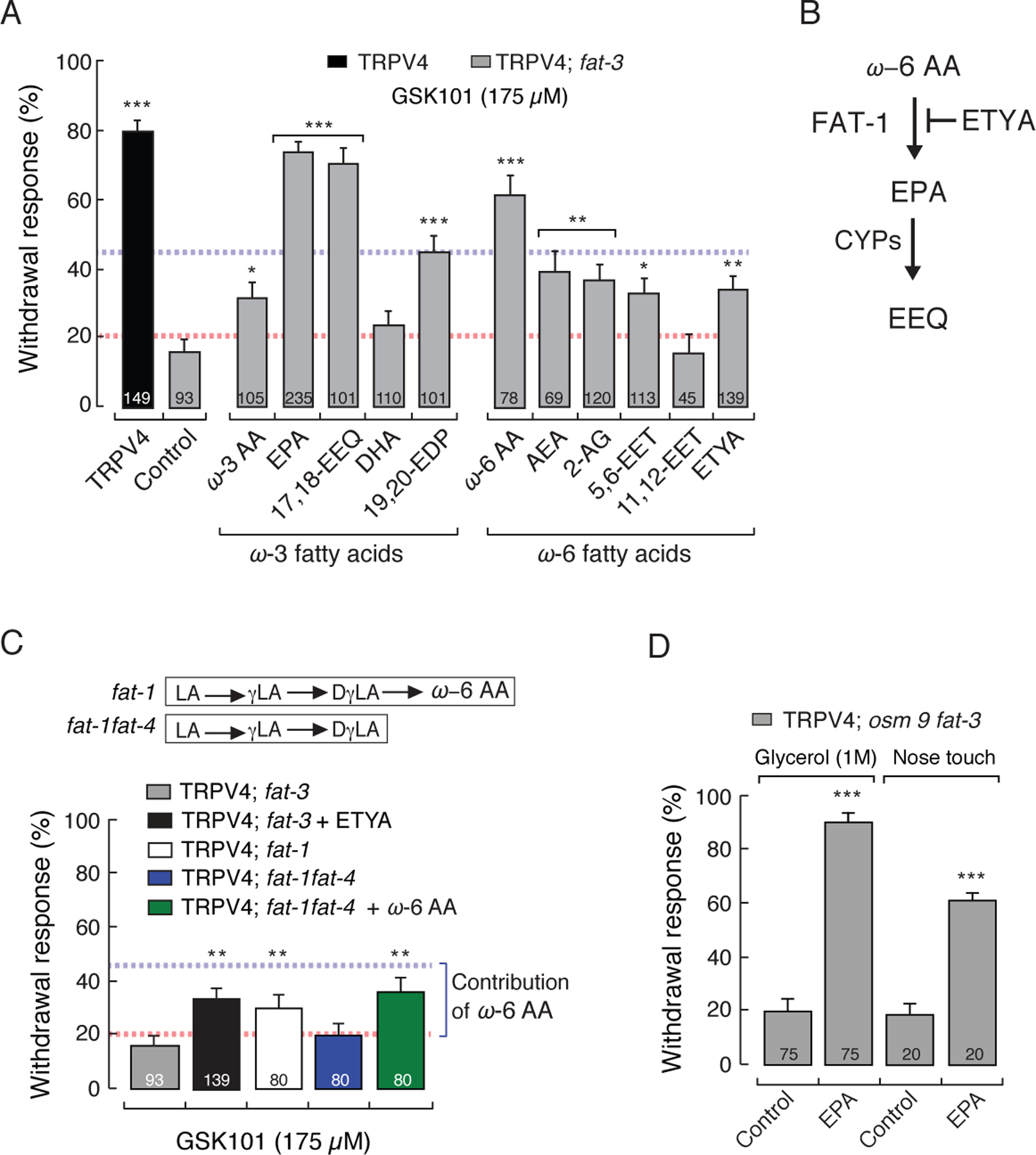

To screen in vivo the individual contribution of PUFAs and their eicosanoid derivatives for their ability to restore the chemically mediated response in TRPV4; fat-3 worms, we performed a series of diet supplementation assays. Remarkably, we observed that supplementation with EPA or its eicosanoid derivative 17,18-EEQ resulted in complete recovery of the withdrawal response (Figure 3A), demonstrating that TRPV4 is regulated by ω-3 fatty acid metabolism. It is noteworthy that 17,18-EEQ has been shown to be a potent vasodilator in human pulmonary arteries (Morin et al., 2009), but its targets are largely unknown. We also observed that ω-3 AA and the eicosanoid 19,20-epoxy docosapentaenoic acid (19,20-EDP) restored 35–45% of the withdrawal response (Figure 3A; response below blue line), whereas DHA had no effect. TRPV4; fat-3 worms supplemented with DHA, efficiently incorporated this PUFA through their diet, as shown by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) fatty acid profiles (Figure S3A), even though they do not respond to GSK101. Furthermore, the slow growth phenotype of fat-3 mutants reverted when supplemented with PUFAs [Figure S3B and elsewhere (Watts et al., 2003)]; indicating that DHA was incorporated by the worms. Unlike its metabolite 19,20-EDP, DHA does not carry an epoxide group, supporting a key role for the cyclic ether (Figure S3C). On the other hand, we found that ω-6 fatty acid-derived metabolites such as anandamide (AEA), 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), 5,6-EET, and eicosatetraynoic acid (ETYA) restored 20–45% of the withdrawal responses (Figure 3A; responses below blue line); in contrast, 11,12-EET had no effect.

Figure 3.

EPA and 17,18-EEQ fully restore TRPV4 function in C. elegans. (A) GSK101-mediated withdrawal responses of TRPV4 and TRPV4; fat 3 mutants after worms were fed with specified PUFAs and eicosanoid derivatives (200 µM). Dotted red and blue lines represent the 20% and 45% thresholds for positive and intermediate responses, respectively. (B) Schematic representation of the effect of ETYA (non-metabolizable analogue of ω-6 AA) in worms. (C) Top inset, ω-6 PUFAs present in fat-1 and fat-1fat-4. Bottom, withdrawal responses elicited by GSK101 in TRPV4; fat-3, TRPV4; fat-3 supplemented with ETYA, TRPV4; fat-1, TRPV4; fat-1fat-4, and TRPV4; fat-1fat-4 supplemented with ω-6 AA. (D) Withdrawal responses elicited by 1 M glycerol and nose touch in TRPV4; osm9fat-3 mutants after being fed with EPA (200 µM). Bars are mean ± SEM, the number of worms tested during 3 assays sessions is indicated inside the bars. The asterisks indicate values significantly different from control. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, and *p < 0.05. See also Figure S3.

Intriguingly, we observed a robust response when TRPV4; fat-3 worms were supplemented with ω-6 AA (Figure 3A) and wondered how significant is the contribution of ω-6 fatty acids to TRPV4 function. The fatty acid cascade in Figure 2A shows that ω-6 AA can be further metabolized by FAT-1 into EPA. Therefore, the response reported after supplementation with ω-6 AA could reflect a contribution from ω-6 AA, EPA, and/or their metabolites. To differentiate between the contribution of ω-6 and ω-3 fatty acids to TRPV4 function, we used a structural analog of ω-6 AA that cannot be metabolized (ETYA). Supplementation of TRPV4; fat-3 worms with ETYA mimics a TRPV4; fat-3 worm that contains ω-6 AA but not EPA (Figure 3B). Because withdrawal responses of TRPV4; fat-3 worms were significantly lower (35%) in worms supplemented with ETYA than in those supplemented with ω-6 AA (Figure 3A), we concluded that the behavior observed with ω-6 AA supplementation was not entirely due to this fatty acid but rather due to its conversion into ω-3 PUFAs (i.e., EPA) and/or its metabolites. Next, we further addressed the influence of ω-6 PUFAs in TRPV4 function by genetically separating the contribution of ω-6 AA and EPA using two strains: TRPV4; fat-1 and TRPV4; fat-1fat-4. We found that TRPV4; fat-1 and TRPV4; fat-1fat-4 worms supplemented with ω-6 AA (which chemically mimics TRPV4; fat-1) responded slightly better than TRPV4; fat-3 and TRPV4; fat-1fat-4 worms (~15 % more over the red line; Figure 3C). These results confirm that the withdrawal responses after supplementing TRPV4; fat-3 worms with ω-6 AA are mainly due to its conversion into EPA by FAT-1; thus, the net contribution of ω-6 AA is ~15% of the withdrawal response. Moreover, the lack of withdrawal responses of TRPV4; fat-1fat-4 worms demonstrates that ω-6 PUFAs upstream of ω-6 AA (LA, γLA, and DγLA) are not required for TRPV4 function (Figure 3C). Because TRPV4; osm-9fat-3 worms failed to respond to osmotic and mechanical stimuli (Figure 2E), we also tested the ability of EPA to restore these behaviors. EPA supplementation recovered TRPV4; osm-9fat-3 worm’s responses to 1 M glycerol and nose touch (Figure 3D). Based on our chemical and genetic screens, the only fatty acids that increase TRPV4; fat-3 worms’ withdrawal responses above 45% are EPA and its eicosanoid derivative 17,18-EEQ (a potent vasodilator); hence, we concluded that ω-3 PUFAs are required for TRPV4 function.

ω-3 PUFAs Enhance TRPV4 Activity in Endothelial Cells

TRPV4 channels are evenly distributed throughout the plasma membrane of HMVEC; however, most of the channels do not open even during maximal GSK101 stimulation (Sullivan et al., 2012). The function of these silent (unresponsive to agonists) TRPV4 channels in HMVEC remains unknown. Because our previous results demonstrate that EPA and 17,18-EEQ are required for TRPV4 activity in C. elegans, we reasoned that silent TRPV4 channels in HMVEC could be the result of limited levels of these ω-3 PUFAs; if this is true, then supplying EPA to cultured HMVEC should make these channels available for activation. Indeed, we found that EPA supplementation resulted in an ~3-fold increase in TRPV4 ionic currents (90.40 ± 6.9 pA/pF) versus no treatment (26.86 ± 3.3 pA/pF; Figures 4A-B and S4A) when cells were chemically challenged with GSK101. In contrast, cultured HMVEC supplemented with ω-6 AA showed no significant differences in TRPV4 currents (30.66 ± 8.62 pA/pF) compared to untreated cells (Figure 4B). Because we used a saturating concentration of GSK101 (100 nM), these results support the idea that EPA treatment facilitates the transition between a silent state (unresponsive to agonists) and one in which TRPV4 is available for activation by chemical stimuli. Importantly, we did not observe changes in the single channel conductance when HMVEC are supplemented with EPA (Control = 4.05 ± 0.17 vs. EPA-treated= 4.2 ± 0.1; Figure S4B-C) and/or in the mean open times (1–6 ms; Figure S4D), suggesting that the increase in currents with EPA treatment is likely due to activation of previously silent channels. TRPV4 undergoes a desensitization process in the presence of Ca2+ (5 mM) when activated with heat and phorbol (Watanabe et al., 2002b); thus, we asked whether EPA-treatment also affects TRPV4 desensitization. Indeed, we observed that EPA treatment decreases TRPV4 Ca2+-dependent desensitization in HMVEC, when compared to control treatment, as evidenced by the ratio between the peak current and the current after 5 mins (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

EPA supplementation enhances TRPV4 activity in HMVEC. (A) Representative whole-cell patch-clamp recordings (+80 mV) of control and EPA (100 µM)-treated HMVEC challenged with GSK101 (100 nM) and HC067047 (10 µM). (B) Box plots show the mean, median, standard deviation, and standard error of the mean from TRPV4 currents (IGSK101- IHC / pF) obtained by whole-cell patch-clamp recordings (+80 mV) of control, EPA-, and ω-6 AA-treated HMVEC. (C) Left, representative current-voltage relationships determined by whole-cell patch-clamp recording of control and EPA (100 µM)-treated HMVEC challenged with GSK101 (100 nM) in the presence of 5 mM Ca2+. Right, bar graph of peak currents (at +80 mV) relative to the currents after 5 min of exposure to GSK101 (I max/I 5 min). Bars are mean ± SEM. (D) HMVEC were challenged with isosmotic (IB, 320 mOsm), hyposmotic (HB, 240 mOsm), and GSK101 (100 nM) solutions and analyzed for their responses using Ca2+ imaging (Fluo-4 AM); color bar indicates relative change in fluorescence intensity. Control and EPA (100–300 µM)-treated HMVEC were analyzed from 5 independent preparations. (E) Representative traces corresponding to normalized (ΔF/F) intensity changes of individual cells shown in (D). (F) Area under the curve of control and EPA-treated HMVEC challenged with hyposmotic buffer. Bars are mean ± SEM. The number of endothelial cells measured is indicated below the boxes and inside the bars. The asterisks indicate values significantly different from control. ***p < 0.001 and **p < 0.01. See also Figure S4.

It is well known that TRPV4 responds downstream of osmotic changes (White et al., 2016); hence, we sought to determine whether EPA supplementation influences TRPV4 response to hyposmotic stimulus in HMVEC. To this end, we measured fluorescence changes in HMVEC loaded with a Ca2+-sensitive dye (Fluo-4 AM) as a readout of TRPV4-mediated activity. We found a marked difference in the osmotic response profile, such that cells supplemented with EPA displayed prolonged responses along with higher fluorescence intensities (Figures 4D-E). This is clearly appreciated when analyzing the area under the fluorescence intensity elicited by the hyposmotic stimulus (Figure 4F) and the average cell response between both groups (Figure S4E), where EPA-treated cells duplicate the intensity values for control cells. Furthermore, the fluorescence changes upon hyposmotic stimulation were absent in both experimental conditions in the presence of TRPV4 antagonist HC067047 (Figures S4F). Collectively, the increase in ionic currents elicited by GSK101 and decrease in channel desensitization together with the differences in osmotic responses between EPA-treated and control cells are consistent with a model whereby ω-3 PUFAs enhance TRPV4 function in HMVEC.

EPA Treatment Increases ω-3 Eicosanoid Derivatives but Does Not Affect TRPV4 Expression in Endothelial Cells

We used LC-MS to determine the content of the entire fatty acid classes and metabolite changes in HMVEC under the same conditions used in our electrophysiological recordings and imaging experiments (with and without EPA; Figures 5A-B). We found that control cells have high content of ω-6 AA and marginal amounts of EPA (Figure 5A, black bars), whereas EPA treatment increases this fatty acid but lowers the content of ω-6 AA (Figure 5A, red bars). In control conditions where ω-6 AA is intrinsically high, we observed low TRPV4 activity (Figures 4B and 5A). Moreover, among the EEQ series, we found that 17,18-EEQ (which recovered the withdrawal response in TRPV4; fat-3 worms) reached the highest concentration among the ω-3 eicosanoid derivatives in HMVEC after EPA treatment (Figure 5B). On the other hand, we observed slight changes on DHA eicosanoids content after EPA supplementation. Hence, our results show that increased TRPV4 activity correlates with higher content of EPA and 17,18-EEQ in HMVEC.

Figure 5.

EPA supplementation increases ω-3 fatty acid eicosanoid derivatives in HMVEC and does not affect TRPV4 expression and trafficking. (A) EPA and ω-6 AA content in control and EPA (100 µM)-treated HMVEC, as determined by LC-MS. (B) ω-6 AA, EPA, and DHA eicosanoid derivatives content in control and EPA-treated HMVEC, as determined by LC-MS. (C) TRPV4 expression levels detected in control and EPA-treated HMVEC by immunostaining. (D-E) Western blots with anti-TRPV4 antibody in control and EPA-treated HMVEC from total protein extracts (D) and membrane protein fractions (E). Normalized relative intensities (RI) against total protein present in the PVDF membranes (Figure S5) are denoted. Similar results were observed in at least five independent Western blots. See also Figure S5.

We next asked whether the increase in TRPV4 currents in EPA-cultured HMVEC is due to the opening of previously silent channels in the plasma membrane, rather than an increase in protein trafficking. In agreement with our C. elegans imaging results (Figures 2F-G), we observed no obvious differences in TRPV4 expression levels between control and EPA-treated HMVEC (Figure 5C) after immunostaining analysis. Likewise, total protein extracts and membrane protein fractions showed similar TRPV4 expression levels for control and EPA-treated HMVEC after normalizing by the total amount of protein present in the PVDF membranes (Figures 5D-E and S5). Taken together, our data support that silent TRPV4 channels at the plasma membrane of HMVEC are the result of low levels of ω-3 PUFAs and/or their eicosanoid derivatives.

ω-3 Fatty Acid Content Alters the Physical Properties of Membranes

PUFAs and their eicosanoid derivatives, when free or part of phospholipids, could modulate TRPV4 activity by altering the physical properties of the membrane (e.g., fluidity and stiffness). By using DSC, we measured changes in heat capacity profiles (ΔTm) as a readout for membrane fluidity and structural disorder of synthetic membranes (1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, DPPC) containing PUFAs and their eicosanoid derivatives. We found that the epoxide group (a cyclic ether with a three-atom ring; Figure S6A) contained in 17,18-EEQ and 5,6-EET reduces the Tm, heat capacity, and the cooperativity among lipids as observed by the broadening of the main melting peak compared to their fatty acid precursors EPA and ω-6 AA, respectively (Figures 6A-B). Notably, 17,18-EEQ promoted a larger shift in Tm towards lower temperatures compared to 5,6-EET (~1.7x; Figure 6B), demonstrating that 17,18-EEQ has a larger influence in membrane structural disorder. The ability of 17,18-EEQ to increase the fluidity of synthetic membranes correlates with our results in C. elegans and HMVEC, in which augmentation of 17,18-EEQ enhanced TRPV4 activity compared to 5,6-EET.

Figure 6.

ω-3 PUFAs contribute to membrane fluidity and bending stiffness. (A) Thermotropic characterization of the DPPC/PUFA systems using differential scanning calorimetry; control (Tm = 41.68 ºC), ω-6 AA (41.04 ºC), EPA (40.85 ºC), 5,6-EET (39.36 ºC), and 17,18-EEQ (37.85 ºC). (B) Effect of DPPC/PUFAs on melting temperatures (∆Tm) with respect to DPPC membranes. We plotted ΔTm absolute magnitude to better illustrate the effect. Experiments were performed from two independent preparations. Bars are mean obtained during two liposome assay sessions. (C) Top, schematic representation of the atomic force microscopy setup on HMVEC. Bottom, representative force distance traces acquired at 10 µm/s and magnification of the force step for control and EPA (300 µM)-treated cells. (D) Box plots show the mean, median, and the 75th to 25th percentiles analysis from tether forces of control and EPA-treated cells. The number of endothelial cells measured during two sessions is indicated below the boxes. The asterisks indicate values significantly different from control. ***p < 0.001. See also Figure S6.

To directly determine whether ω-3 PUFAs affect the mechanical properties of HMVEC plasma membranes, we measured the mean tether forces of control and EPA-treated cells using AFM (Figure 6C). Tether force measurements allow determination of the effective plasma membrane fluidity and bending stiffness (Vasquez et al., 2014). We found that the mean tether force for control HMVEC (24 ± 8.2 pN; Figure 6C-D) agrees with the magnitude reported for human umbilical vein endothelial cells (29 ± 10 pN) (Sun et al., 2005). Remarkably, we observed that EPA treatment significantly decreased the mean tether force of HMVEC (18 ± 5 pN) when compared to control (Figure 6C-D). Therefore, HMVEC plasma membranes enriched in EPA and 17,18-EEQ display high membrane fluidity and low bending stiffness, unlike control HMVEC that have high content of ω-6 AA and its metabolites (Figure 5A-B).

We tested the ability of 5,6-EET, 17,18-EEQ, and EPA to directly alter TRPV4 function, by perfusing these fatty acids on TRPV4-expressing HEK293 cells. Using whole-cell patch-clamp recordings, we found a slight increase in ionic currents after fatty acids addition (~5% of total GSK101 currents; Figure S6B). These results further support the concept that ω-3 PUFAs alter channel function mainly via altering membrane mechanics rather than through a direct activation mechanism. In view of our fatty acids screen, biophysical and functional characterizations, we propose that the epoxide group’s location towards the end of the aliphatic chain in 17,18-EEQ (Figure S6A) modulates TRPV4 function by altering the mechanical properties of the plasma membrane.

Discussion

Diets rich in ω-3 PUFAs are associated with a protective effect on cardiovascular health (Mori, 2014). The emerging hypothesis for how ω-3 PUFAs exert their effects include gene expression, receptor signaling, and plasma membrane remodeling (Barden et al., 2016). Several lines of evidence support that ω-3 PUFAs and their eicosanoid derivatives regulate TRPV4 activity. First, we showed that TRPV4 worms lacking free long PUFAs and/or contained in phospholipids do not respond to chemical or physical stimuli in C. elegans. Second, supplementation assays established that 17,18-EEQ increases TRPV4 activity. Third, we found that HMVEC plasma membranes enriched with ω-3 PUFAs display high membrane fluidity and low bending stiffness. Our findings support a model whereby ω-3 PUFAs could modulate endothelial cell reactivity by altering membrane physical properties, which in turn governs the number of TRPV4 channels available for activation and decreasing Ca2+-dependent desensitization.

The precise mechanism by which TRPV4 responds to mechanical stimuli is an ongoing debate (White et al., 2016). Three mechanisms of TRPV4 activation after mechanical stimulation have been proposed: AA metabolites (Vriens et al., 2004; Watanabe et al., 2003), purinergic signaling (Mamenko et al., 2011), and membrane stretch (Liedtke et al., 2003; Loukin et al., 2010). Recently, it has been shown that TRPV4 is activated by mechanical stimulation applied at cell-substrate contact points (Servin-Vences et al., 2017). Although TRPV4 plays a role in mechanosensation, how membrane composition modulates channel function is largely unknown.

We propose a model in which 17,18-EEQ, a product of the ω-3 fatty acid metabolism, provides a membrane environment favorable for TRPV4 function (Figure 7A), in which channels outside of such membrane domains do not open by chemical and physical stimuli (Figure 7B). Instead, TRPV4 channels surrounded by an ω-3 enriched membrane environment are available to be activated (Figures 7C-D); and when active TRPV4 Ca2+ -dependent desensitization decreases. This seems to be an efficient mechanism for increasing intracellular Ca2+ and modulating vascular reactivity since cells would use TRPV4 channels already at the plasma membrane. It is tempting to speculate that ω-3 fatty acids modulate TRPV4 function by increasing its sensitivity to mechanical and chemical stimuli. Our model can potentially explain why there are silent (unresponsive to agonists) TRPV4 channels in HMVEC when cultured in standard media (Sullivan et al., 2012). Targeting silent TRPV4 channels with ω-3 PUFA-like molecules (Figure 7A, blue channels) might be a promising strategy to regulate vascular reactivity.

Figure 7.

Proposed model by which ω-3 fatty acids enhance human endothelial cells response. Plasma membranes with reduced levels of ω-3 fatty acid displays low number of channels available for activation (A) as well as a reduced number of active channels after stimulation (B). ω-3 fatty acids enriched plasma membranes increase the number of channels available for activation (C) as well as the number of active channels after stimulation (D).

17,18-EEQ is an eicosanoid derivative that displays cardiovascular-protective properties, including antihypertensive and antithrombotic effects in several animal models (Fleming, 2014). How does 17,18-EEQ influence TRPV4 function? Notably, ω-3 PUFAs are known to influence membrane lipid dynamics and structural organization (Mason et al., 2016). Our findings are consistent in that ω-3 PUFAs increase membrane fluidity and decrease bending stiffness; particularly, we observed that 17,18-EEQ has a larger effect than 5,6-EET on membrane mechanics. Within this framework, we propose that the hydrophilic epoxide group of 17,18-EEQ, located towards the end of the aliphatic chain (Figure 7 inset; light blue acyl chain and S6A), interacts with water molecules at the membrane’s lipid/water interface. This leads to bending of the fatty acid tail toward the phospho-head groups, reducing the van der Waals interactions between lipid molecules and consequently the Tm of the system. These changes could impact TRPV4 activity by altering the sensitivity to physical and chemical stimuli. Moreover, our data demonstrate that ω-3 PUFAs have a stronger effect on TRPV4 function when they are part of the membrane rather than via a direct mechanism of activation. Interestingly, hypotonic shock activates TRPV4 in yeast internal membranes in the absence of PUFAs (Loukin et al., 2009); however, it remains to be determined whether this membranes contain lipids with eicosanoid-like properties that enhance TRPV4 function. Overall, our results support that TRPV4 activation is favored by changes in membrane fluidity, and, possibly changes of lateral pressure caused by the epoxide’s location.

The force-from-lipids principle supports the idea that membrane force changes influence the energy needed to drive conformational rearrangements that in turn modulate protein function (Teng et al., 2015). Prokaryotic and eukaryotic mechanosensitive ion channels are hallmarks of this principle, as their amphipathic helices transduce changes in the membrane forces to drive channel gating (Bavi et al., 2016; Brohawn et al., 2014). In this context, membranes enriched with ω-3 PUFAs could decrease the energetic barrier and favor TRPV4 activation by chemical and physical stimuli. Interestingly, it has been shown that interaction between TRPV4 and PIP2 is required for channel activation by hypotonic and heat stimuli (Garcia-Elias et al., 2013). Based on our results, we envision that fatty acid composition alters the local TRPV4 phospholipid microenvironment, favoring membrane protein interaction and modulating channel gating. Future experiments could be directed to determine TRPV4 lipid microenvironment in the presence or absence of fatty acids. Moreover, changes in fatty acid composition could favor the interaction between the S4-S5 linker with the inner leaflet of the membrane; such protein-membrane interaction has been shown to be important for TRPV4 response to GSK101 and cell swelling (Teng et al., 2016). Alternatively, a recent study has demonstrated that the proximity of a kinase anchor protein (AKAP150)-associated PKCα increases TRPV4 channel opening (Tajada et al., 2017); hence, it is possible that plasma membranes enriched with ω-3 PUFAs could favor AKAP150-TRPV4 interaction and enhance channel activity.

The data presented here provide a molecular framework for understanding the effects of ω-3 PUFAs in the vascular system. By increasing TRPV4 channels available for activation at the plasma membrane, ω-3 PUFAs add a level of regulation of TRPV4 in human vascular endothelial cells. Future experiments will help determine whether ω-3 PUFAs regulate TRPV4 channels in other cells and/or other ion channels. Beyond the role of TRPV4 in the cardiovascular system, understanding how TRPV4 is modulated by fatty acids might have important implications for inflammatory processes.

Experimental Procedures

Strains.

Worms were propagated as described (Brenner, 1974). A complete list of strains is presented in Supplementary Table I.

Behavioral Assays.

Drop Test. Behavioral trials were performed by placing a drop containing control buffer or different agonists in front of moving young adult hermaphrodites as described (Hart, 2006). Agonists included GSK1016790A, 4α-phorbol 12,13-didecanoate (Sigma-Aldrich), and capsaicin (Tocris Bioscience). Behavioral responses of stable genome-integrated (i) TRPV4 worms are shown on Figure S2E-F. Nose Touch Assay. Worms were tested for their ability to avoid mechanical stimuli as previously described (Geffeney et al., 2011). Diet Supplementation. Fatty acids and metabolites were obtained from Nu-Chek Prep and Cayman Chemical, respectively. HC-067047 was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. NGM was supplemented with 0.1% Tergitol and 200 µM PUFAs or eicosanoids. HC-067047 (DMSO) was added to NGM to reach a 2 µM.

Worms Imaging.

Worms were paralyzed on 1% agarose pads containing 150 mM of 2,3-butanedione monoxime and imaged with an objective C-Apochromat 63x/1.2 W Corr water immersion lens on a confocal microscope (Zeiss Axiophot 200 LSM Pascal) and images were analyzed with FIJI (Schindelin et al., 2012).

RNAi Feeding.

To knock down mboa-6 expression, NGM plates were seeded with E. coli HT115 containing mboa-6 double-stranded RNAi-containing plasmid, as previously described (Matsuda et al., 2008).

Cells Culture and Electrophysiology.

Primary cells.

HMVEC from neonatal human dermal donor isolates were obtained at passage 4 from Cell Systems Corporation. Cells were cultured according to the manufacturer’s protocol and used up to the 7th passage. HMVEC cells were supplemented with 100 µM EPA or ω-6 AA overnight prior to electrophysiological measurements. For whole-cell recordings, the bath solution contained (in mM): 140 NaCl, 6 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4). The pipette solution contained 140 CsCl, 5 EGTA, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.2). For the desensitization experiments the bath solution contained 5 mM CaCl2. Macroscopic currents were recorded using a 500 ms ramp from −80 mV to +80 mV delivered once per second.

Calcium Imaging.

HMVEC cells were supplemented with 300 µM EPA overnight prior to imaging experiments. HEK293 cells and HMVEC were loaded with Fluo-4 AM (1 µM) per manufacturer’s protocols. Images were acquired and analyzed with CellSens. The isotonic solution contained (in mM): 105 NaCl, 5 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, and 90 Mannitol (320 mOsm) pH 7.3. For the hypotonic stimulation, the solution contained: 105 NaCl, 5 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose (240 mOsm) pH 7.3. Data analysis was performed off-line using MATLAB (version 7.10.0, The MathWorks Inc., 2010).

Protein Expression Determination.

Western blot. HMVEC were collected and treated as follows: 1) For total protein extracts, cells were mechanically lysed with RIPA buffer (Santa Cruz) supplemented with protein inhibitors, and spun down at 10,000g for 10 min at 4 °C. 2) For membrane protein fractions, cells were sonicated in PBS pH 7.4 (with protease inhibitors) and spun down at 8,000g. Supernatant was spun down at 160,000g for 1 h at 4°C. Membrane pellets were solubilized with 2% SDS and spun down at 160,000g for 1 h at RT. Supernatants from total protein extract and membrane protein fractions were loaded in Mini-PROTEAN TGX Stain-free Precast gels and were exposed to UV for 45s before transfer. Anti-TRPV4 (1:200, Santa Cruz) and IRDye® 800CW Donkey Anti-Rabbit secondary antibodies (1:10,000, LI-COR) were used for western blots. Membranes were developed in a LI-COR and ChemiDoc Touch imaging system (Bio-Rad), for infrared and UV signals, respectively. Immunostaining. HMVEC were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min; permeabilization was achieved with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min. HMVEC were incubated with primary anti-TRPV4 antibody (1:250; Alomone Cat # ACC-124) at 4 °C overnight. Samples were washed and incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody conjugated to goat anti-rabbit IgG-TR (1:200 Cat # sc-2780). Fluorescence was detected with a Zeiss Axiophot 200 LSM Pascal.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry.

DPPC (1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, 4 mM) was dissolved in ethanol and mixed with specified fatty acids. Lipid mixtures containing 5 mol% of individual PUFAs were evaporated. Lipid mixtures were hydrated with 10 mM HEPES (pH 7) at ~50°C. To yield multilamellar vesicles, the suspension was vortexed and incubated for 1 h at ~50°C. Samples were degassed at 635 mmHg for 10 min at 3 °C and equilibrated for 5 min at 4 °C, prior to DSC experiments. Measurements were performed on a NanoDSC microcalorimeter (TA instruments). Thermograms were recorded at a constant scan rate of 1 °C/min (between 10–60 °C), pressure of 3 atm, and analyzed with Nano Analyze.

Atomic Force Microscopy.

HMVEC were supplemented with 300 µM EPA overnight prior measurements. AFM experiments were carried out as previously described (Krieg et al., 2008) with an Asylum Research MFP3D. AFM cantilevers (Budget Sensors) were coated for 1 h with 1 mg/ml peanut lectin in PBS pH 7.4; calibrated per the thermal noise method (Hutter and Bechhoefer, 1993) with a spring constant of 15.9 pN/nm. Membrane tethers were pulled at 10 µm/sec from HMVEC after 500 ms contact time. Cell-cantilever contacts yielded 40% and 15% single- and multiple- tether events, respectively; for multiple events, forces were characterized by the length of the last observed tether (Sun et al., 2005). Tether forces were determined using MATLAB from force–distance curves displaying unbinding events.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Instat 3 Software (GraphPad Inc.). Non-normally distributed data were compared using Mann-Whitney rank test for two independent groups (Figures 1C, 1D, 2D, 2E, 2I, 3D, 4C, 4F, 6D), and Kruskall-Wallis and Dunn’s (post hoc) comparison tests for multiple independent groups (Figures 1B, 1E, 2B, 2C, 3A, and 3C). Normally distributed data were compared using One-way ANOVA (Figure 2G) and post hoc Bonferroni test (Figure 4B).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Drs.: J.C. Ruiz-Suárez (DSC) and E. Lindner (AFM) for providing access to instruments; Dr. K.U. Malik for experimental advice; Drs. A. Chesler, R.C. Foehring, Mr. L.O. Romero for critically reading the manuscript; Drs. C. Bargmann and M.B. Goodman for providing worm strains and Dr. H. Arai for providing RNAi. Strains were obtained from Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440). We used the lipidomics Core Facility at Wayne State University (National Institutes of Health Grant S10RR027926). This work was supported by the AHA (15SDG25700146) to JFC-M and VV (16SDG26700010).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Barden AE, Mas E, and Mori TA (2016). n-3 Fatty acid supplementation and proresolving mediators of inflammation. Curr Opin Lipidol 27, 26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargmann CI (2006). Chemosensation in C. elegans. In WormBook, Jorgensen E, ed. (The C. elegans Research Community, WormBook, , http://www.wormbook.org/.), pp. 1–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basak S, Schmandt N, Gicheru Y, and Chakrapani S (2017). Crystal structure and dynamics of a lipid-induced potential desensitized-state of a pentameric ligand-gated channel. Elife 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavi N, Cortes DM, Cox CD, Rohde PR, Liu W, Deitmer JW, Bavi O, Strop P, Hill AP, Rees D, et al. (2016). The role of MscL amphipathic N terminus indicates a blueprint for bilayer-mediated gating of mechanosensitive channels. Nat Commun 7, 11984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S (1974). The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohawn SG, Su Z, and MacKinnon R (2014). Mechanosensitivity is mediated directly by the lipid membrane in TRAAK and TREK1 K+ channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111, 3614–3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbert HA, Smith TL, and Bargmann CI (1997). OSM-9, a novel protein with structural similarity to channels, is required for olfaction, mechanosensation, and olfactory adaptation in Caenorhabditis elegans. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 17, 8259–8269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earley S, Heppner TJ, Nelson MT, and Brayden JE (2005). TRPV4 forms a novel Ca2+ signaling complex with ryanodine receptors and BKCa channels. Circulation research 97, 1270–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earley S, Pauyo T, Drapp R, Tavares MJ, Liedtke W, and Brayden JE (2009). TRPV4-dependent dilation of peripheral resistance arteries influences arterial pressure. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology 297, H1096–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo J, and Arita M (2016). Cardioprotective mechanism of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Cardiol 67, 22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming I (2014). The pharmacology of the cytochrome P450 epoxygenase/soluble epoxide hydrolase axis in the vasculature and cardiovascular disease. Pharmacol Rev 66, 1106–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Elias A, Mrkonjic S, Pardo-Pastor C, Inada H, Hellmich UA, Rubio-Moscardo F, Plata C, Gaudet R, Vicente R, and Valverde MA (2013). Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-biphosphate-dependent rearrangement of TRPV4 cytosolic tails enables channel activation by physiological stimuli. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110, 9553–9558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geffeney SL, Cueva JG, Glauser DA, Doll JC, Lee TH, Montoya M, Karania S, Garakani AM, Pruitt BL, and Goodman MB (2011). DEG/ENaC but not TRP channels are the major mechanoelectrical transduction channels in a C. elegans nociceptor. Neuron 71, 845–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart AC (2006). Behavior. WormBook, 1–67.

- Hutter JL, and Bechhoefer J (1993). Calibration of atomic-force microscope tips. Rev Sci Instrum 64, 1868–1873. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn-Kirby AH, Dantzker JL, Apicella AJ, Schafer WR, Browse J, Bargmann CI, and Watts JL (2004). Specific polyunsaturated fatty acids drive TRPV-dependent sensory signaling in vivo. Cell 119, 889–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieg M, Helenius J, Heisenberg CP, and Muller DJ (2008). A bond for a lifetime: employing membrane nanotubes from living cells to determine receptor-ligand kinetics. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 47, 9775–9777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke W, Choe Y, Marti-Renom MA, Bell AM, Denis CS, Sali A, Hudspeth AJ, Friedman JM, and Heller S (2000). Vanilloid receptor-related osmotically activated channel (VR-OAC), a candidate vertebrate osmoreceptor. Cell 103, 525–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke W, and Friedman JM (2003). Abnormal osmotic regulation in trpv4−/− mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100, 13698–13703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke W, Tobin DM, Bargmann CI, and Friedman JM (2003). Mammalian TRPV4 (VR-OAC) directs behavioral responses to osmotic and mechanical stimuli in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100 Suppl 2, 14531–14536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loukin S, Zhou X, Su Z, Saimi Y, and Kung C (2010). Wild-type and brachyolmia-causing mutant TRPV4 channels respond directly to stretch force. The Journal of biological chemistry 285, 27176–27181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loukin SH, Su Z, and Kung C (2009). Hypotonic shocks activate rat TRPV4 in yeast in the absence of polyunsaturated fatty acids. FEBS Lett 583, 754–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamenko M, Zaika O, Jin M, O’Neil RG, and Pochynyuk O (2011). Purinergic activation of Ca2+-permeable TRPV4 channels is essential for mechano-sensitivity in the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron. PloS one 6, e22824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason RP, Jacob RF, Shrivastava S, Sherratt SC, and Chattopadhyay A (2016). Eicosapentaenoic acid reduces membrane fluidity, inhibits cholesterol domain formation, and normalizes bilayer width in atherosclerotic-like model membranes. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1858, 3131–3140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda S, Inoue T, Lee HC, Kono N, Tanaka F, Gengyo-Ando K, Mitani S, and Arai H (2008). Member of the membrane-bound O-acyltransferase (MBOAT) family encodes a lysophospholipid acyltransferase with broad substrate specificity. Genes Cells 13, 879–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori TA (2014). Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: epidemiology and effects on cardiometabolic risk factors. Food Funct 5, 2004–2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin C, Sirois M, Echave V, Rizcallah E, and Rousseau E (2009). Relaxing effects of 17(18)-EpETE on arterial and airway smooth muscles in human lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 296, L130–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peixoto-Neves D, Wang Q, Leal-Cardoso JH, Rossoni LV, and Jaggar JH (2015). Eugenol dilates mesenteric arteries and reduces systemic BP by activating endothelial cell TRPV4 channels. Br J Pharmacol 172, 3484–3494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall AS, Liu CH, Chu B, Zhang Q, Dongre SA, Juusola M, Franze K, Wakelam MJ, and Hardie RC (2015). Speed and sensitivity of phototransduction in Drosophila depend on degree of saturation of membrane phospholipids. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 35, 2731–2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, et al. (2012). Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 9, 676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servin-Vences M, Moroni M, Lewin GR, and Poole K (2017). Direct measurement of TRPV4 and PIEZO1 activity reveals multiple mechanotransduction pathways in chondrocytes. Elife 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonkusare SK, Bonev AD, Ledoux J, Liedtke W, Kotlikoff MI, Heppner TJ, Hill-Eubanks DC, and Nelson MT (2012). Elementary Ca2+ signals through endothelial TRPV4 channels regulate vascular function. Science 336, 597–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strotmann R, Harteneck C, Nunnenmacher K, Schultz G, and Plant TD (2000). OTRPC4, a nonselective cation channel that confers sensitivity to extracellular osmolarity. Nature cell biology 2, 695–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MN, Francis M, Pitts NL, Taylor MS, and Earley S (2012). Optical recording reveals novel properties of GSK1016790A-induced vanilloid transient receptor potential channel TRPV4 activity in primary human endothelial cells. Mol Pharmacol 82, 464–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M, Graham JS, Hegedus B, Marga F, Zhang Y, Forgacs G, and Grandbois M (2005). Multiple membrane tethers probed by atomic force microscopy. Biophysical journal 89, 4320–4329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson D, Block R, and Mousa SA (2012). Omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA: health benefits throughout life. Adv Nutr 3, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajada S, Moreno CM, O’Dwyer S, Woods S, Sato D, Navedo MF, and Santana LF (2017). Distance constraints on activation of TRPV4 channels by AKAP150-bound PKCalpha in arterial myocytes. The Journal of general physiology 149, 639–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng J, Loukin S, Anishkin A, and Kung C (2015). The force-from-lipid (FFL) principle of mechanosensitivity, at large and in elements. Pflugers Archiv : European journal of physiology 467, 27–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng J, Loukin SH, Anishkin A, and Kung C (2016). A competing hydrophobic tug on L596 to the membrane core unlatches S4-S5 linker elbow from TRP helix and allows TRPV4 channel to open. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113, 11847–11852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorneloe KS, Sulpizio AC, Lin Z, Figueroa DJ, Clouse AK, McCafferty GP, Chendrimada TP, Lashinger ES, Gordon E, Evans L, et al. (2008). N-((1S)-1-{[4-((2S)-2-{[(2,4-dichlorophenyl)sulfonyl]amino}-3-hydroxypropanoyl)-1 -piperazinyl]carbonyl}-3-methylbutyl)-1-benzothiophene-2-carboxamide (GSK1016790A), a novel and potent transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 channel agonist induces urinary bladder contraction and hyperactivity: Part I. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 326, 432–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y, Aursnes M, Hansen TV, Tungen JE, Galpin JD, Leisle L, Ahern CA, Xu R, Heinemann SH, and Hoshi T (2016). Atomic determinants of BK channel activation by polyunsaturated fatty acids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113, 13905–13910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin DM, Madsen DM, Kahn-Kirby A, Peckol EL, Moulder G, Barstead R, Maricq AV, and Bargmann CI (2002). Combinatorial expression of TRPV channel proteins defines their sensory functions and subcellular localization in C. elegans neurons. Neuron 35, 307–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez V, Krieg M, Lockhead D, and Goodman MB (2014). Phospholipids that contain polyunsaturated fatty acids enhance neuronal cell mechanics and touch sensation. Cell reports 6, 70–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vriens J, Watanabe H, Janssens A, Droogmans G, Voets T, and Nilius B (2004). Cell swelling, heat, and chemical agonists use distinct pathways for the activation of the cation channel TRPV4. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101, 396–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis JG, Watts JL, and Browse J (2002). Polyunsaturated fatty acid synthesis: what will they think of next? Trends in biochemical sciences 27, 467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H, Davis JB, Smart D, Jerman JC, Smith GD, Hayes P, Vriens J, Cairns W, Wissenbach U, Prenen J, et al. (2002a). Activation of TRPV4 channels (hVRL-2/mTRP12) by phorbol derivatives. The Journal of biological chemistry 277, 13569–13577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H, Vriens J, Prenen J, Droogmans G, Voets T, and Nilius B (2003). Anandamide and arachidonic acid use epoxyeicosatrienoic acids to activate TRPV4 channels. Nature 424, 434–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H, Vriens J, Suh SH, Benham CD, Droogmans G, and Nilius B (2002b). Heat-evoked activation of TRPV4 channels in a HEK293 cell expression system and in native mouse aorta endothelial cells. The Journal of biological chemistry 277, 47044–47051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts JL (2009). Fat synthesis and adiposity regulation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM 20, 58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts JL (2016). Using Caenorhabditis elegans to Uncover Conserved Functions of Omega-3 and Omega-6 Fatty Acids. J Clin Med 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts JL, and Browse J (2002). Genetic dissection of polyunsaturated fatty acid synthesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99, 5854–5859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts JL, Phillips E, Griffing KR, and Browse J (2003). Deficiencies in C20 polyunsaturated fatty acids cause behavioral and developmental defects in Caenorhabditis elegans fat-3 mutants. Genetics 163, 581–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JP, Cibelli M, Urban L, Nilius B, McGeown JG, and Nagy I (2016). TRPV4: Molecular Conductor of a Diverse Orchestra. Physiol Rev 96, 911–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiest EF, Walsh-Wilcox MT, Rothe M, Schunck WH, and Walker MK (2016). Dietary Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Prevent Vascular Dysfunction and Attenuate Cytochrome P4501A1 Expression by 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Toxicol Sci. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.