Abstract

Objectives

Racial identity, which is the degree that individuals define themselves regarding their racial group membership, may influence the mental well-being of Black adults. To gain an understanding of the role Black racial identity may have on postpartum mental health, the researchers performed a secondary data analysis to examine the relationship between six Black racial identity clusters (Low Race Salience, Assimilated and Miseducated, Self-Hating, Anti-white, Multiculturalist, and Conflicted) and postpartum maternal functioning in Black women living in Georgia.

Methods

Black women completed Cross’s Racial Identity Scale, the Barkin Index of Maternal Functioning, and demographic questionnaires online via Qualtrics®.

Participants

A total sample of 116 self-identified Black postpartum women were included in the analysis. Women ranged in age from 18 to 41 years (M = 29.5 ± 5.3) and their infants were 1 to 12 months old (M = 5.6 ± 3.5). The majority of women were married/cohabitating with their partner (71%), had a college degree (53%), and employed (69%).

Results

It was determined through Kruskal Wallis test, χ2(5) = 20.108, p < 0.05, that the women belonging to the Assimilated and Miseducated cluster had higher levels of maternal functioning when compared to the women in the Self-Hating and Anti-white clusters.

Conclusion

This study is novel in its exploration of the relationship between Black racial identities and postpartum maternal functioning. Findings support the need for further research with larger sample and cluster sizes to determine the relationship between racial identity and maternal functioning.

Keywords: Racial identity, Maternal functioning, Postpartum depression, Black women

Significance Statement

What is already known about this subject?

Various external and personal factors influence Black women’s willingness to be vulnerable and express their difficulties in adjusting to motherhood with their healthcare providers. Innovative and culturally sensitive assessment tools are needed to identify Black women who may have difficulty caring for themselves and their child.

What does this study add?

This study examined Black women’s racial identities, a concept shown to correlate with psychological distress in Black adults, and their postpartum maternal functioning abilities to identify those who may need support in adjusting to motherhood. Findings support the need for further research with larger sample and cluster sizes to determine the relationship between racial identity and maternal functioning.

Introduction

Various external and personal factors influence Black women’s willingness to express their difficulty in adjusting to motherhood, especially to their health care providers. Culturally, there is an unrealistic expectation within the Black community that Black women should be superwomen, strong and invulnerable regardless of traumatic or life-altering events, i.e., childbirth and motherhood (Woods-Giscombe et al., 2016). This cultural norm may cause Black women to portray the image of being a “perfect mother” or ignore internal signals regarding their mental or physical health (Woods-Giscombe et al., 2016). Additionally, Black women may have a distrust in healthcare due to its extensive history of inadequate and unethical treatment towards Black Americans (Chambers et al., 2021). Black women with mental health diagnoses may also be criminalized and deemed an unfit parent (Lash, 2017). For example, Black children are placed into Child Protective Services (CPS) due to maternal mental illness more frequently than families of other races (Roberts, 2002). Further, internalized racism may cause Black women to develop low self-esteem and hopelessness due to their acceptance and endorsement of anti-Black rhetoric and beliefs (Jones, 2000). Cultural influences and structural racism may cause Black women to suppress their postpartum mental health concerns and persevere despite difficulties, while internalized racism may negatively affect Black women’s mental and emotional well-being, resulting in psychological distress (Carter & Reynolds, 2011). Regardless of the scenario, cultural influences and various levels of racism may result in Black women experiencing psychological distress but reluctant to seek help, including during the time after childbirth. Innovative assessment tools that consider these factors should be used to identify those who may have difficulty adjusting to caring for themselves and their infant and who may need resources or mental health services. Maternal functioning and Black racial identity are constructs that may provide an alternative way to assess the psychological state and adjustment to motherhood in Black postpartum women.

Maternal functioning is the ability of a woman to perform tasks related to caring for their infant while responding to their own needs (Barkin et al., 2010a, 2010b). Maternal functioning is an important factor that deserves examination among Black women because it may reflect cultural influences on their ability to balance caring for their infant while caring for themselves (Woods-Giscombe et al., 2016). Maternal functioning focuses on maternal skill-building, including the achievement of balance, maintenance of self-care, and indicators of mental health to include postpartum depression (Barkin et al., 2017). This is the first study, to our knowledge, to consider the relationship of maternal functioning to Black women’s racial identity.

Black racial identity describes one’s internalized attitudes about being Black in America (Worrell et al., 2004). Although race is an arbitrary construct created by society to categorize people based on their physical appearance and attributes (Gordon, 2008), it reflects the racism often experienced by Black women throughout their lifespan, which can negatively affect their physical and mental health (Chambers et al., 2021; Jones, 2000). Consequently, Black women’s experienced and/or internalized racism can influence their dissociation from or the embrace of their race being central to their identity (Nuru-Jeter et al., 2009). There is scientific evidence that racial identity correlates with Black people’s psychological distress and functioning (Carter & Reynolds, 2011; Forsyth & Carter, 2012). Black people who hold a negative regard toward their race experience higher levels of depression and anxiety (Hurd et al., 2013; Worrell et al., 2011), while those with a strong hate for white people may experience paranoia, depression, and hostility (Hurd et al., 2013; Worrell et al., 2011). Additionally, Black people with a strong sense of pride in being Black are less likely to report depressive symptoms than those with a negative regard for being Black (Neblett et al., 2013). However, a prior study (Floyd James et al., 2021) did not find an association between racial identity and postpartum depressive symptoms in Black women. Since maternal functioning may serve as a proxy for postpartum depressive symptoms (Barkin et al., 2017), it is prudent to investigate the relationship between maternal functioning and racial identity types in postpartum Black mothers to determine possible associations.

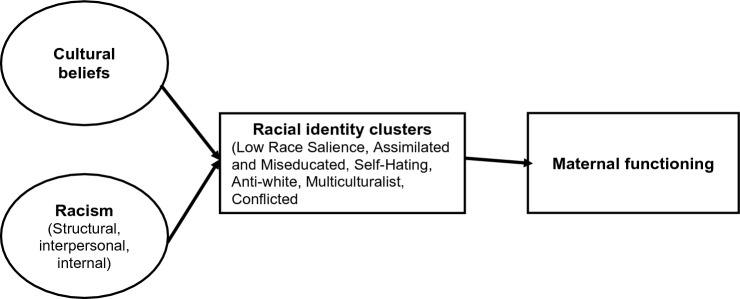

The Becoming a Mother theory (BAM), adapted to include the construct of racial identity to incorporate the influence of Black race, was used to guide this study. The BAM theory describes how women transition and adapt to motherhood by caring for themselves, their infant, and balancing other responsibilities (Mercer, 1995). Maternal functioning is necessary for women to reconcile their previous responsibilities with the new tasks of motherhood (Barkin et al., 2010b). While the BAM theory considers various factors that may influence the transition into motherhood, e.g., mental health or social support (Mercer, 1995), Black women’s racial identity, which is often influenced by experienced racism and/or internalized racism throughout one’s lifetime, is not considered (Nuru-Jeter et al., 2009). The theoretical adaptation allowed the researchers to understand the role Black racial identity may have on postpartum mental health, that can inform the development of holistic postpartum emotional and functional assessment tools. Because maternal functioning is associated with mental health the aim of this study was to examine the relationship between maternal functioning and racial identities in postpartum Black mothers (Fig. 1). We hypothesized that maternal functioning levels would differ by racial identity clusters such that (1a) racial identity clusters associated with negative regard for the Black race (Low Race Salience, Assimilated and Miseducated, Self-Hating, Multiculturalist) will have lower levels of maternal functioning, and (1b) racial identity clusters associated with positive regard for the Black race (Anti-white, Conflicted) will have higher levels of maternal functioning.

Fig. 1.

Integrated theoretical framework of racial identity and Becoming a Mother theory

Methods

This study is a secondary analysis of a cross-sectional study designed to examine and describe the racial identity attitudes of postpartum Black women living in Georgia (Table 1) (Floyd James et al., 2021). The study also captured data that measured the mental health status of postpartum Black mothers and the interaction with their infant. The original study was conducted in accordance with prevailing ethical principles, and Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from Georgia State University and the Georgia Department of Public Health. Details regarding the original study are available elsewhere (Floyd James et al., 2021).

Table 1.

Racial identity clusters within a sample of Black postpartum women (N = 116)

| Cluster number | Cluster name | n | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Low race salience | 5 | The construct of race is not important to these women. They prefer to create their community and support groups around other common characteristics, such as religion or hobbies |

| 2 | Assimilated and miseducated | 19 | These women may endorse negative stereotypes associated with Black people. They also prefer to identify as American with no emphasis on the race or African ancestry |

| 3 | Self-hating | 12 | These women internalize their negative regard for the Black race. As a result, they hate themselves because they are Black |

| 4 | Anti-white | 25 | These women hold a strong hate for the white race because of experienced racism. They may also be experiencing some uncertainty with their racial identity, so they are learning more about Afrocentric activities and culture |

| 5 | Multiculturalist | 42 | These women accept and socialize with people of various cultural, racial, or sexual identity groups but do not place high importance on Black pride or Afrocentric beliefs/thoughts |

| 6 | Conflicted | 13 | These women embody several different racial identities which may seem incongruous. These women may have hate for white people but also feel the need to assimilate with the white race. These women endorse negative stereotypes of Black people while also having a sense of pride in being Black |

Adapted from (Floyd James et al., 2021)

Sample

A non-random sample of participants was drawn throughout the state of Georgia by using digital and printed flyers in various locations, i.e., social media platforms, pediatric and women’s healthcare offices, salons, universities, and childcare facilities. Women were eligible to participate in the original study if they (1) self-identified as Black; (2) were 18 years or older with an infant 12 months or younger; (3) and had no characteristics that increased their risk for developing postpartum depression (PPD). These criteria included no history of mental illness, most recent birth being a singleton, no extended parent–child separation, and no children, including most recent birth, with chronic health conditions. A total of 137 women were recruited, met eligibility criteria, and were enrolled; 21 participants who were missing data needed to calculate their maternal functioning score were excluded. Thus, the analytical sample includes 116 women with complete data. Assuming 80% power and 0.15 effect size, the target sample size was achieved. The participants completed questionnaires anonymously and privately online via Qualtrics® after electronic consent was provided.

Instruments

Participant Characteristics

Participant characteristics were obtained to describe the sample. Age, age of their youngest child, number of dependent children, birth type (vaginal or cesarean), employment status (full-time, unemployed, part-time, full-time), healthcare insurance (Medicaid/Medicare, employer sponsored, none), educational level (did not complete high school, high school diploma or General Education Diploma (GED), associate or technical degree, college or graduate degree), relationship status (single or married/cohabitating with partner), and income level (less than $26,000, $26,000–$49,999, $50,000-$74,999, $75,000–$149,999, $150,000 or more) were assessed by self-report in the Qualtrics® survey.

Black Racial Identity

Participants’ racial identity was measured using the Cross Racial Identity Scale (CRIS), which is a 40-item survey using a seven-point Likert scale with six subscales (assimilation, miseducation, self-hatred, anti-white, Afrocentricity, and multiculturalist); each subscale has five items. Subscale scores range from 1 to 7 with higher scores reflecting stronger endorsements of the corresponding racial identity attitude. In previous research that included Black women from the ages of 18–43, the Cronbach alpha of the CRIS ranged from 0.76 to 0.91 (Worrell et al., 2011). In the original study, the subscales had high reliability as well (α = 0.79–0.87). The original study used hierarchical cluster analysis to group participants with similar racial identity subscale scores. This statistical analytic method was used to reflect the complexity of racial identity in Black postpartum women and resulted in six racial identity clusters being identified: Low Race Salience, Assimilated and Miseducated, Self-hating, Anti-white, Multiculturalist, and Conflicted. The full details of the process and description of the clusters have been published elsewhere (Floyd James et al., 2021), but Table 1 provides the name, size, and description for each of the six previously identified racial identity clusters used in this analysis.

Maternal Functioning

The Barkin Index of Maternal Functioning (BIMF) was developed in 2010 to assess postpartum maternal functional status in a sample of postpartum women, which included Black women (Barkin et al., 2010a, 2010b). The index has 20 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale. Total scores range from 0 to 120, with higher scores indicating higher maternal functioning. The 20-item BIMF has been validated in a study with Black women in the sample (Barkin et al., 2017); the Cronbach alpha was 0.83, reflecting adequate internal consistency. The Cronbach alpha in this study was 0.84. Barkin et al. (2014) conducted a study with 346 women in which a factor analysis identified all key interpretability criteria and revealed a two-factor structure.

Data Analysis

All data were analyzed using the IBM® SPSS® software, version 27.0.1.0 for Mac. For non-categorical variables, bivariate relationships with maternal functioning were examined via Spearman’s rho analysis. Associations between maternal functioning and sociodemographic variables with three or more categories were examined using the Kruskal–Wallis test. The Kruskal–Wallis test was also used to examine differences between the six Black racial identity clusters (Low Race Salience, Assimilated and Miseducated, Self-Hating, Anti-white, Multiculturalist, and Conflicted) with respect to maternal functioning scores. See Table 1 for descriptive information of the racial identity clusters.

Results

The 116 participants were self-identified Black women who ranged in age from 18 to 41 years; the average age was 34 years. Their infants were 1 to 12 months old, with an average age of 5 months. Most participants (62%) had vaginal births, a high school education or beyond (93%), were employed (69%), married/living with a partner (71%), and used Medicaid (55%) for their birth. The median household income was between $35,000 and $49,000. The mean maternal functioning score was 97.4 (± 13.3); scores ranged from 42 – 120, which respectively represents the lowest and highest functioning woman within the sample.

Differences in Maternal Functioning Among Racial Identity Clusters

A Kruskal–Wallis test was conducted to determine if there were differences in maternal functioning scores between groups that differed in their Black racial identity cluster membership: Low Race Salience (n = 5), Assimilated and Miseducated (n = 19), Self-Hating (n = 12), Anti-white (n = 25), Multiculturalist (n = 42), and Conflicted (n = 13). Mean rank maternal functioning scores were significantly different between the Black racial identity clusters, χ2(5) = 20.108, p = 0.001. Subsequently, pairwise comparisons of racial identity clusters were performed using Dunn's procedure with a Bonferroni correction (Polit, 2010) for multiple comparisons. Adjusted p-values are presented in Table 2. Of the six previously identified racial identity clusters, post hoc analysis determined that three—Assimilated and Miseducated, Self-Hating, and Anti-white—were significantly associated with maternal functioning. Black women in the Assimilated and Miseducated cluster (Mdn = 106) had the highest level of maternal functioning scores when compared to the other two clusters. This post hoc analysis revealed significant differences in maternal functioning scores between the following racial identity clusters: Assimilated and Miseducated (Mdn = 106) and Self-Hating (Mdn = 89.5) (p = 0.002), and the Assimilated and Miseducated (Mdn = 106) and Anti-white (Mdn = 94) (p = 0.008), but not between any other racial identity cluster combinations.

Table 2.

Analysis of variance results for Black postpartum women’s maternal functioning scores by racial identity cluster membership (N = 116)

| Cluster | n | Median | H | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low race salience | 5 | 101 | 20.108 | 5 | .00 |

| Assimilated and miseducated | 19 | 106* | |||

| Self-hating | 12 | 89.5* | |||

| Anti-white | 25 | 94* | |||

| Multiculturalist | 42 | 99 | |||

| Conflicted | 13 | 95 |

As measured by the Barkin Index of Maternal Functioning

*p < .05 Dunn’s pairwise test with Bonferroni correction

Discussion

This sample of Black postpartum women had an overall high level of maternal functioning (M = 97.4). This study excluded women currently diagnosed with or who had a history of mental health conditions, thereby minimizing the likelihood that the sample would have low maternal functioning. In a sample of women with moderate to severe symptoms of postpartum depression, the mean BIMF score was 70 (Geller et al., 2018), levels much lower than the women in this study. After the women in the Geller et al. study (2018) completed an intensive, outpatient mental health program, their depressive symptoms lessened and BIMF scores increased to 89, indicating an improvement in maternal functioning. Future research should include women with positive and negative screens for postpartum depression to examine maternal functioning more accurately within this population.

Additionally, for decades Black women and families, especially low-income families receiving public assistance, have been at an increased risk of being reported to CPS by professionals (Lash, 2017; Roberts, 2002). Because most women in this study used Medicaid, they may view CPS as a threat and therefore provided answers which reflected a higher level of maternal functioning. Lastly, despite most women in this study being married/cohabitating with their partner, the average maternal functioning score was lower than that of studies predominantly comprised of unpartnered Black mothers (Barkin et al., 2017). Barkin et al. (2017) found that married women’s postpartum functioning scores were 4-points lower than single women. Poor relationship quality, non-supportive partner (Cohen et al., 2019), and dissatisfaction with sexual intimacy negatively influence postpartum women’s mental well-being (Faisal-Cury et al., 2021) and consequently, maternal functioning. The married women in this study were possibly overwhelmed due to cultural expectations of being superwoman. These mothers may be caring for others while neglecting themselves, performing most childcare activities and household responsibilities without asking for their partner’s help (Woods-Giscombe et al., 2016), which could lead to decreased maternal functioning. Future research should characterize and distinguish married women’s transition into motherhood, with a focus on relationship quality and partner support to better understand the role cultural expectations have on Black women’s maternal functioning.

The most prevalent racial identity clusters were Multiculturalist, Anti-White, and Assimilated and Miseducated (Table 1). The hypothesis was partially supported in that women in the Self-Hating cluster had one of the lowest levels of maternal functioning. However, contrary to the hypothesis, we found that participants within the Assimilated and Miseducated racial identity cluster had the highest level of maternal functioning, while those in the Anti-white clusters had the lowest. A few of the racial identity clusters in this study are relatively new or slightly different than those previously identified. Low Race Salience is an ambiguous racial identity, so there are conflicting findings regarding its correlation to mental health and functioning in Black adults (Floyd James et al., 2021; Worrell et al., 2006). Additionally, the Multiculturalist cluster in this study had low scores in the Afrocentric subscale, indicating the women in this cluster did not place high importance on being Black. This is different than previous studies (Hurd et al., 2013; Worrell et al., 2006) because Black adults in this racial identity cluster typically have positive scores in the Afrocentric and Multiculturalist subscale. These differences in cluster subscale scores may account for the differing findings in this study.

Previous studies determined that Black women whose racial identity attitude favored assimilation with the white race experienced anger, depression, confusion, and fatigue (Carter & Reynolds, 2011). These taxing psychological symptoms may be due to Black peoples’ frustration with not being fully accepted by the white race, despite their best efforts (Mohammad Almenia, 2019). Because the women in this Assimilated and Miseducated cluster endorsed negative stereotypes of Black people, their dissociation from their Black race and ability to assimilate with the white race may allow them to avoid the symptoms of psychological distress associated with experienced racism or anti-Black rhetoric or behavior, which in this study, is reflected as higher maternal functioning scores. The women in the Self-Hating cluster had lower maternal functioning scores, when compared to the women in the Assimilated and Miseducated cluster. This finding is similar to previous research which found that Black adults with Self-Hating racial identities had low self-esteem, high levels of depression, and symptoms of psychological distress (Hurd et al., 2013; Neblett et al., 2013; Worrell et al., 2011). Black people with Self-Hating attitudes may have been told how their Afrocentric features, such as their kinky hair or dark skin are bad, and their mere existence is inadequate (Pogue White, 2002). This internalized hate may then manifest as difficulty in caring for themselves and/or their infant in Black postpartum women. Lastly, the women in the Anti-white cluster had lower maternal functioning scores than those in the Assimilated and Miseducated cluster. Black people with an Anti-white racial identity may immerse themselves in Black culture due to experiencing or witnessing anti-Black racism (Worrell et al., 2006). The original study was conducted during the spring of 2020, a time in America when racism and police brutality were at the forefront (Buchanan et al., 2020). This may have caused the women in this cluster to dislike white people and develop a heightened awareness to racial issues (Neville & Cross, 2017), resulting in increased stress levels or depression (Wilson, et al., 2017) and lower maternal functioning abilities.

Due to the prevalence of experienced racism by Black women (Chambers et al., 2021; Nuru-Jeter et al., 2009) and its psychological impact, it is of great concern that there is potential for many Black women to have difficulties adjusting to motherhood. Because low levels of maternal functioning may indicate postpartum depression, the women with Self-Hating and Anti-white racial identities need to receive mental health counseling to spark conversations around their self-hatred (Pogue White, 2002), experiences with racism, and other stressors (Wilson et al., 2017). These Black women may find strength in changing the superwoman narrative to one that includes self-care and self-preservation (Scott, 2017), developing a relationship with a Black or culturally competent mental healthcare provider who encourages them to remove their “superwoman cape”, be vulnerable, and begin to improve their quality of life and transition into motherhood. Overall, when the BIMF was used in conjunction with the CRIS, Black women who may be experiencing lower levels of maternal functioning due to their internalized struggles with their racial identity or experienced racism were identified. Future research needs to further explore the relationship between racial identity and mental well-being or distress in postpartum Black women, while also including the various levels and types of racism as a stressor that also affects their mental health.

Limitations and Strengths

Strengths of this study include being the first to assess the relationship between Black racial identity and functioning abilities of postpartum women. Because Black women are often undiagnosed or hesitant to disclose struggles in caring for themselves and/or their infant, this study begins to address the lesser explored reasons which may contribute to this health disparity.

There were limitations to this study that should be considered when interpreting its findings. Women were recruited from a single geographic area without detailed information about the area, e.g., urban, or rural, or demographics of participants’ community. Future research should capture this data so inferences can be made on the influence community demographics have on Black women’s racial identity. Most women were in their late twenties, partnered and educated, which limit the generalization of findings. The coronavirus pandemic began affecting Georgians a month after the initiation of the original study. During that time, recruitment efforts were online or word of mouth, which could affect the representativeness of the sample. Furthermore, the inclusion criteria minimized the possibility of enrolling women with factors that may increase their risk for poor maternal functioning. Relatedly, the inclusion criteria also yielded a sample with varying time passed since childbirth, allowing some women longer time periods to adapt to motherhood, which could influence the overall functioning scores of the sample. Future research should include a more homogenous sample of postpartum women with respect to time since giving birth or account for differences in the analyses. The influence of birth type, e.g., cesarean, or vaginal, on maternal functioning should also be examined in future research.

Conclusions

In summary, this study was the first to explore the relationship among lesser-known concepts, racial identity, and maternal functioning in Black postpartum women. The data suggests that racial identity attitudes correlate with women’s ability to care for themselves and their infants. Black postpartum women who have assimilated with white American culture may have higher levels of maternal functioning while those who internalize anti-Black thoughts or hold extreme anger towards white people may have lower levels of maternal functioning. Future research is needed to explore the relationship between maternal functioning, Black racial identities, experienced racism, and their utility to holistically identify Black women who are having difficulty adjusting to motherhood and managing their various responsibilities.

Author Contributions

Kortney Floyd James and Dawn M. Aycock took the lead in writing and organizing the manuscript. All authors contributed to the concept, analysis, and/or interpretation of data. All authors critically revised the draft manuscript, reviewed and gave approval of the final manuscript before submitting for publication.

Funding

This research was supported by two grants from (1) Women’s Health Research Fund, funded by the Georgia Dept of Public Health, North Central Health District and (2) Georgia State University School of Nursing Kaiser Permanente Doctoral Scholarship.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest with the research or writing of this paper.

Ethical Approval

This study has been approved by the Georgia Department of Public Health IRB on March 15, 2020 with approval #200307 and the Georgia State University IRB on April 3, 2020 with approval number H20409. Therefore, the study has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection, with a consent form administered through Qualtrics.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Barkin JL, Mckeever A, Lian B, Wisniewski SR. Correlates of postpartum maternal functioning in a low-income obstetric population. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2017;23(2):149–158. doi: 10.1177/1078390317696783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkin JL, Wisner KL, Bromberger JT, Beach SR, Terry MA, Wisniewski SR. Development of the barkin index of maternal functioning. Journal of Women’s Health. 2010;19(12):2239–2246. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkin JL, Wisner KL, Bromberger JT, Beach SR, Wisniewski SR. Assessment of functioning in new mothers. Journal of Women's Health. 2010;19(8):1493–1499. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkin JL, Wisner KL, Wisniewski SR. The psychometric properties of the Barkin index of maternal functioning. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing. 2014;43(6):792–802. doi: 10.1111/1552-6909.12505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, L., Bui, Q., & Patel, J. K. (2020). Black Lives Matter may be the largest movement in U.S. History. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/03/us/george-floyd-protests-crowd-size.html.

- Carter R, Reynolds A. Race-related stress, racial identity status attitudes, and emotional reactions of Black Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2011;17(2):156–162. doi: 10.1037/a0023358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers BD, Arega HA, Arabia SE. Black women’s perspectives on structural racism across the reproductive lifespan: A conceptual framework for measurement development. Maternal Child Health Journal. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10995-020-03074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MJ, Pentel KZ, Boeding SE, Baucom DH. Postpartum role satisfaction in couples: Associations with individual and relationship well-being. Journal of Family Issues. 2019;40(9):1181–1200. doi: 10.1177/0192513X19835866. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faisal-Cury A, Tabb K, Matijasevich A. Partner relationship quality predicts later postpartum depression independently of the chronicity of depressive symptoms. Revista Brasileira De Psiquiatria. 2021;43(1):12–21. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2019-0764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd James, K., Aycock, D. M., Barkin, J. L., & Hires, K. A. (2021). Examining the relationship between black racial identity clusters and postpartum depressive symptoms. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 27(4), 292–305. 10.1177/10783903211002650 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Forsyth J, Carter A. The relationship between racial identity status attitudes, racism-related coping, and mental health among Black Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2012;18(2):128–140. doi: 10.1037/a0027660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller PA, Posmontier B, Horowitz JA, et al. Introducing Mother Baby Connections: A model of intensive perinatal mental health outpatient programming. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2018;41:600–613. doi: 10.1007/s10865-018-9974-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon LR. An introduction to Africana philosophy. Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hurd NM, Sellers RM, Cogburn CD, Butler-Barnes ST, Zimmerman MA. Racial identity and depressive symptoms among Black emerging adults: The moderating effects of neighborhood racial composition. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49(5):938–950. doi: 10.1037/a0028826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CP. Levels of racism: A theoretic framework and a gardener's tale. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(8):1212–1215. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.8.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lash, D. (2017). Parents with disabilities. In When the welfare people come [eBook edition]. (p. 88). Haymarket Books.

- Mercer R. Becoming a mother: Research on maternal identity from Rubin to the present. Springer Publishing Company; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad Almenia M. Elevating social status by racial passing and white assimilation: In George Schuyler’s Black No More. AWEJ for Translation & Literary Studies. 2019 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3483745. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Jr, Banks KH, Cooper SM, Smalls-Glover C. Racial identity mediates the association between ethnic-racial socialization and depressive symptoms. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2013;19(2):200–207. doi: 10.1037/a0032205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neville HA, Cross WE. Racial awakening: Epiphanies and encounters in Black racial identity. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2017;23(1):102–108. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuru-Jeter A, Dominguez TP, Hammond WP, Leu J, Skaff M, Egerter S, Jones CP, Braveman P. "It's the skin you're in": African American women talk about their experiences of racism. An exploratory study to develop measures of racism for birth outcome studies. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2009;13(1):29–39. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0357-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogue White K. Surviving hating and being hated: Some personal thoughts about racism from a psychoanalytic perspective. Contemporary Psychoanalysis. 2002;38(3):401–422. doi: 10.1080/00107530.2002.10747173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D. F. (2010). Chi-square and nonparametric tests. In Statistics and data analysis for nursing research. (p. 183). Pearson Education Inc.

- Roberts, D. (2002). Shattered bonds: The color of child welfare. [eBook edition]. Basic Civitas Book.

- Scott, K. (2017). Self-care for strong sistas. In The language of strong Black womanhood: Myths, models, messages, and a new mandate for self-care (pp. 55–68). Lexington Books.

- Wilson SL, Sellers S, Solomon C, Holsey-Hyman M. Exploring the link between Black racial identity and mental health. Journal of Depression and Anxiety. 2017;6(3):1–4. doi: 10.4172/2167-1044.1000272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woods-Giscombe C, Robinson MN, Carthon D, Devane-Johnson S, Corbie-Smith G. Superwoman schema, stigma, spirituality, and culturally sensitive providers: Factors influencing African American women’s use of mental health services. Journal of Best Practices in Health Professions Diversity: Research, Education, and Policy. 2016;9(1):1124–1144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worrell FC, Mendoza-Denton R, Telesford J, Simmons C, Martin JF. Cross Racial Identity Scale (CRIS) scores: Stability and relationships with psychological adjustment. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2011;93(6):637–648. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2011.608762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worrell FC, Vandiver BJ, Cross WE. The cross racial identity scale: Technical manual. 2. Author; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Worrell FC, Vandiver BJ, Schaefer BA, Cross WE, Fhagen-Smith PE. Generalizing nigrescence profiles. The Counseling Psychologist. 2006;34(4):519–547. doi: 10.1177/0011000005278281. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Not applicable.