Abstract

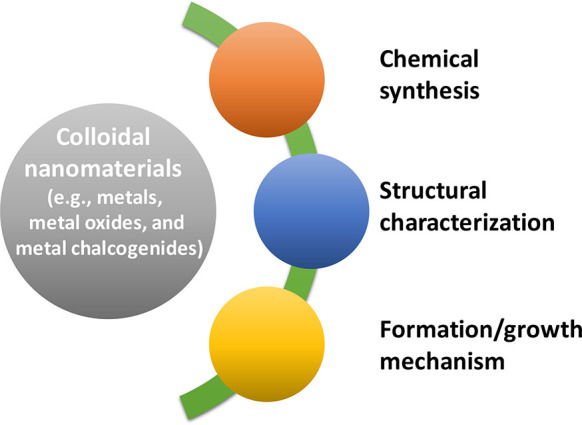

Colloidal nanomaterials of metals, metal oxides, and metal chalcogenides have attracted great attention in the past decade owing to their potential applications in optoelectronics, catalysis, and energy conversion. Introduction of various synthetic routes has resulted in diverse colloidal nanostructured materials with well-controlled size, shape, and composition, enabling the systematic study of their intriguing physicochemical, optoelectronic, and chemical properties. Furthermore, developments in the instrumentation have offered valuable insights into the nucleation and growth mechanism of these nanomaterials, which are crucial in designing prospective materials with desired properties. In this perspective, recent advances in the colloidal synthesis and mechanism studies of nanomaterials of metal chalcogenides, metals, and metal oxides are discussed. In addition, challenges in the characterization and future direction of the colloidal nanomaterials are provided.

Keywords: Nanoparticles, Colloidal Synthesis, Characterization, Nucleation, Formation Mechanism

1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, continued intense research interest in materials at the nanoscale (i.e., at least one dimension below 100 nm) has driven the evolution of a highly multidisciplinary research area, nanomaterials chemistry or nanoscience. It connects researchers from chemistry, physics, biology, and engineering. The colloidal method is one of the primary synthetic protocols of nanomaterials, including metals and metal chalcogenides. It is capable of controlling the size, composition, and morphology of nanoparticles, which have been critical parameters in the advancement of materials science.1,2 In addition to colloidal synthesis, understanding the formation mechanism of nanomaterials is essential to expand basic scientific research. In addition, it helps design prospective materials for catalysis, which addresses problems related to energy conversion, fine chemical synthesis, and environment.3,4

The molecular precursors or monomers have been considered to condense by either classical or nonclassical nucleation in the colloidal synthesis of nanomaterials.5−7 The classical nucleation theory assumes high thermodynamic barriers in homogeneous nucleation. Suppression of the random nucleation enables short bursts of nucleation under high supersaturation, subsequently producing uniformly sized nanoparticles. On the other hand, in the nonclassical nucleation,8 the high-energy barrier of homogeneous nucleation is found to be overcome through distinct metastable nanostructures possessing unique atomic arrangements.

The significant advancements in the synthetic and characterization methods have helped uncover various nonclassical growth phenomena, including stepwise phase transition, aggregation, coalescence, and oriented attachment.9−12 Furthermore, nanoclusters, the ultrasmall molecular intermediate species with unique electronic and geometric structures, have been identified during the colloidal synthesis of metal, metal oxide, and semiconductor nanocrystals. Study of the optical and chemical properties of the nanoclusters has advanced our understanding of the evolution of molecularity and optoelectronic properties in nanomaterials.13−18

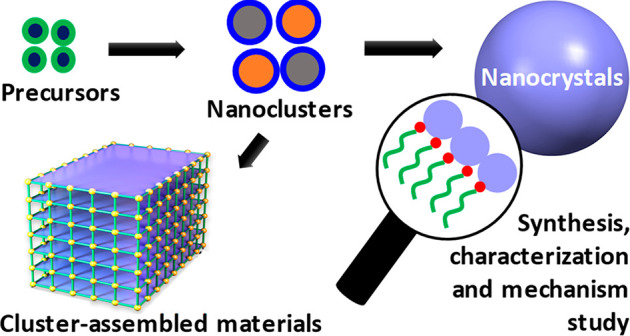

This perspective focuses on the recent advances and prospects in the colloidal synthesis and property characterization of various types of nanomaterials (Scheme 1), including quantum nanostructures, nanoclusters, and assemblies of metal chalcogenides and metal oxides. The surface and three-dimensional (3D) structural characterizations of colloidal nanocrystals using advanced characterization techniques are discussed. Furthermore, nucleation and growth mechanism studies of nanocrystals are highlighted. In the end, challenges and future direction of the colloidal nanomaterials are offered.

Scheme 1. Representation of Key Themes Discussed in This Perspective.

2. Advances in Colloidal Nanomaterial Synthesis

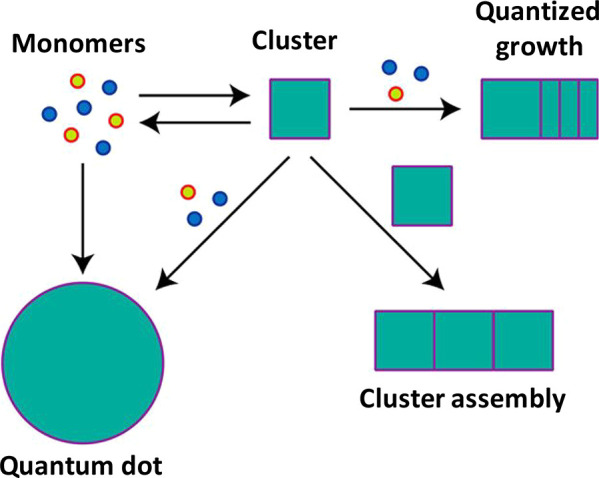

The colloidal synthesis of nanoparticles has generally been understood by the classical nucleation and growth model—burst formation of nuclei and their separated growth.19 In the classical crystallization model, the boundary between the monomeric units and the crystalline materials formed from them is clear based on the large differences in their physical characteristics. On the other hand, identification of such boundaries during the formation of nanoscale materials is challenging since the changes are not abrupt. The intermediate structures, resulting from the stabilization effect of ligands, with close or indistinguishable boundaries, profoundly influence the overall synthetic processes.5 Furthermore, the nonclassical phenomena in the nanoscale materials, such as stepwise phase transition and aggregation, readily imply that the energetics of nucleation and growth cannot be generalized in a single unified theory.

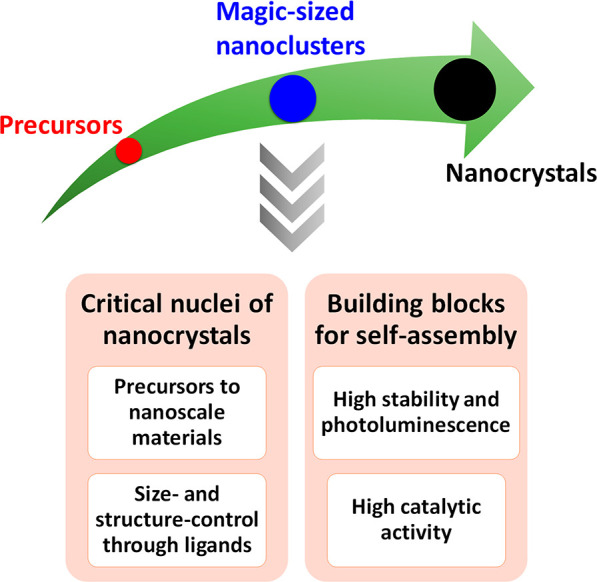

Notably, several time-resolved characterization methods have shown that the synthesis of nanocrystals of metals and metal chalcogenides proceeds through distinct steps involving molecular intermediates with intrinsic stability.20−22 Such unique metastable species composed of tens to hundreds of atoms of metals and/or metal chalcogenides, the so-called nanoclusters or magic-sized nanoclusters (MSCs), are crucial in establishing the elusive molecule-to-solid transition. Besides, the nature and the binding strength of the ligands with the nanocrystals are very important variables in the controlled colloidal synthesis of nanocrystals with uniform size and enhanced stability.23,24 In general, they have been achieved through the judicious choice of ligands, including those of organic and inorganic sources.25,26 In this section, we discuss the recent advances in the synthesis of nanostructures through or from nanoclusters (Scheme 2). Furthermore, the ligand-based engineering of nanomaterials for potential applications is elaborated.

Scheme 2. Depiction of the Formation of Nanocrystals through MSC Intermediates, Which Offer Several Possibilities in Designing Materials with New Properties.

2.1. Nanostructured and Self-Assembled Materials from Nanoclusters

Atomically defined semiconductor MSCs with a single stoichiometric composition offer intriguing chemical27 and photophysical14,28,29 properties that differ from the ensemble averages in nanocrystal samples. The MSCs show narrower absorption features compared to the nanocrystal counterparts due to strong quantum confinement effects.30 The mechanisms by which the MSCs are converted to nanostructured materials are explored with a focus on cluster assembly and monomer-driven growth (Figure 1).31 Under certain reaction conditions, such as high reaction temperatures and diluted nanocluster solutions, the nanoclusters dissolve back to monomers. Then, the supersaturated monomers result in the growth of quantum dots (QDs). Under appropriate conditions, such as low temperature and alkyl amine ligand protection, the MSCs assemble and form lamellar bilayer templates through hydrophobic interactions among ligands.32,33 Such templated MSCs have been shown to serve as building blocks or precursors for the anisotropic growth of semiconductor nanomaterials.31,34 It is worth noting that MSCs could not be preserved during their transformation to different nanostructures, because it is generally performed at mild to high temperatures (70–250 °C).35,36

Figure 1.

Schematic summarizing the role of cluster molecules in the synthesis of nanostructured materials. Adapted with permission from ref (31). Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society.

The limited ambient stability of MSCs prevents the implementation of their properties in practical applications.37,38 The self-assembly of nanoparticles is adapted to enhance stability and to effectively harvest their collective optoelectronic and plasmonic properties.39−42 Similarly, inorganic–organic hybrid materials built from the assembly of inorganic building blocks and organic linkers have shown several potential applications, including CO2 capture and catalysis.39,43 Recently, the concept of assembling inorganic building blocks through organic linkers was successfully applied to metal clusters44 and nanocrystals.45

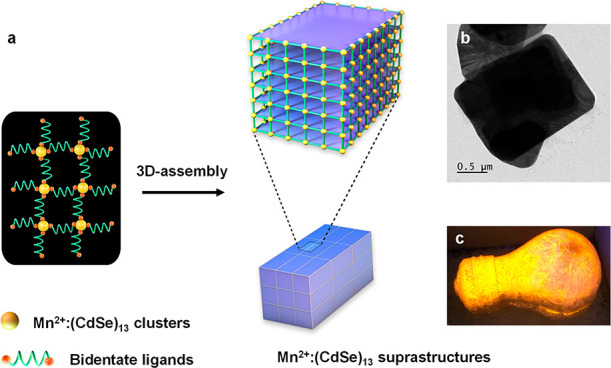

Inspired by the periodic assembly of the metal cluster nodes through organic linkers in metal organic frameworks (MOFs),43,46 our research group38 has pursued the self-assembly of colloidal semiconductor MSCs to form 3D and 2D suprastructures (SSs) in order to overcome instability issues and further boost their properties simultaneously. The self-assembly process is based on the use of aliphatic diamines and mild temperature (Figure 2). The Mn2+-doped MSCs of (CdSe)13 and (ZnSe)13, denoted as Mn2+:(CdSe)13 and Mn2+:(ZnSe)13, respectively, are self-assembled into micron-sized SSs using butane-1,4-diamine (BDA) ligand at 120 °C. The rigid binding of bidentate BDA ligands preserves MSCs during their self-assembly under the thermal treatment. The SSs of Mn2+:(CdSe)13 and Mn2+:(ZnSe)13 appear as 3D bricks and thin 2D sheets, respectively.38 On the other hand, the MSCs could not be retained in the presence of monodentate butylamine (BA) ligands, wherein MSCs are found to transform into Mn2+:CdSe nanoribbons due to weak hydrophobic interactions in lamellar bilayer templates.

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic representation of the self-assembly of MSCs through a ligand-based approach. (b) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of Mn2+:(CdSe)13 SSs. (c) Digital photograph, of a bulb coated with Mn2+:(CdSe)13 SSs, captured under a UV lamp. Reproduced with permission from ref (38). Copyright 2021 Springer Nature Limited.

The rigid binding and intermediate carbon chain length of the BDA ligand are found to be optimal for the effective self-assembly of MSCs. Diamines with longer carbon chains lose their ability to retain MSCs and guide their assembly. Self-assembled MSCs exhibit high enhancements in both ambient and photostability as well as photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQYs, up to 72%). Interestingly, the atomic-level alloying of Cd and Zn with tunable compositions in SSs is found to modulate the catalytic performance through synergistic effects. The Mn2+:(Cd0.5Zn0.5Se)13 composition has shown highest catalytic performance in CO2 fixation with epoxide. These catalysts are found to be recyclable for more than ten times without compromising catalytic performance owing to the high stability of MSCs in SSs.

In addition to metal chalcogenides, monolayer protected coinage metal nanoclusters have also been used to fabricate self-assembled materials with enhanced photophysical properties.47,48 Recently, we47 have synthesized highly fluorescent (greenish-blue emission with a QY of 90%) gold cluster assemblies through Zn2+-ion-mediated self-assembly of Au4(SRCOO–)4 clusters. The Zn2+ ions interact with the carboxylate groups of the Au4(SRCOO–)4 clusters, leading to the formation of compact gold-cluster assemblies with the rigidified ligand-shell and strong metallophilic interactions. The narrow PL peak (full width at half-maximum: ∼ 25 nm), due to single-sized Au4 clusters, of the assembly is an attractive feature for prospective applications in optoelectronics. Furthermore, the controllable dis/reassembly and the aggregation-dependent strong fluorescence have enabled the utilization of gold cluster assemblies for trackable drug delivery systems. Diphosphine ligands have been shown to be capable of both stabilizing and self-assembling Ag2Cl2 clusters to offer highly enhanced PL with microsecond lifetime.48 In addition to metal ions and ligands, the solvents have also been found to be potential self-assembly modulators. The 1-ethynyladamantane protected (AgAu)34 nanoclusters have been assembled into 1D chain with direct metal–metal bonds, resulting semiconducting properties.49

2.2. Chemistry of Inorganic Ligands

To utilize the intriguing properties of colloidal nanocrystals in optoelectronic devices, such as photovoltaics or photodetector applications, native organic ligands need to be removed for further improvements in highly efficient modules, because the desired distance for efficient charge transport is approximately 1 μm for a solar cell50 and 10–1000 μm for a photodetector.51 The first attempts to remove the organic ligands (usually oleic acid) from as-synthesized QDs were performed on QD films; this was later called solid-state ligand exchange.52 Specifically, in the case of QD solar cells, organic ligand-capped PbS QDs are first spin-cast onto a device substrate to make homogeneous QD films. After the formation of a solid-state QD layer, it is treated with the inorganic ligand solution for the solid-state ligand exchange. Iterations of QD deposition and solid-state ligand exchange are performed to attain the desired thickness of QD films. However, because inorganic ligands are shorter than organic counterparts, QDs capped with inorganic ligands shrink. Consequently, cracks, which cause serious damage to the quality of the QD films, are easily generated on the film. Moreover, the finite penetration depth of the inorganic ligand solution limits the thickness of the QD film that could be deposited in one step. To overcome the crack formation and the inefficient film preparation process, inorganic ligand exchange in biphasic solution is suggested prior to making QD film.53 The biphasic-solution ligand-exchange strategy facilitates the naked eye identification of the ligand exchange process through phase transfer, yielding thick and homogeneous QD films without cracks.

Although the biphasic method is successful for PbS and PbSe QDs capped with oleic acids,54,55 it is not applicable to environmentally friendly CuInSe2 QDs, which are generally capped with oleylamine ligands. Because L-type ligands are tightly bound to the QD surface,56 harsh etching agents, which dissolve metal chalcogenide complexes (MCC) in polar solvents and stabilize the resultant CuInSe2 QDs with MCC inorganic ligands, are treated to remove oleylamine ligands. However, the overall process is laborious, and it also involves toxic reagents,57 which are detrimental to the nanocrystal properties.58 To avoid the lethal, expensive, and time-consuming procedure, a direct synthesis of inorganic ligand-capped QDs in polar solvent has recently been developed.59 The novel method utilizes metal halide salts not only for starting precursor materials but also for ligands to synthesize halide-encapsulated QDs with high conductivity at room temperature. Indeed, their efficiency in photovoltaic devices was superior to that prepared from solution-phase ligand-exchange QDs. Because of the room temperature synthesis, directly prepared QDs have broad size distribution and low crystallinity, and their colloidal stability might not be guaranteed at high temperature.

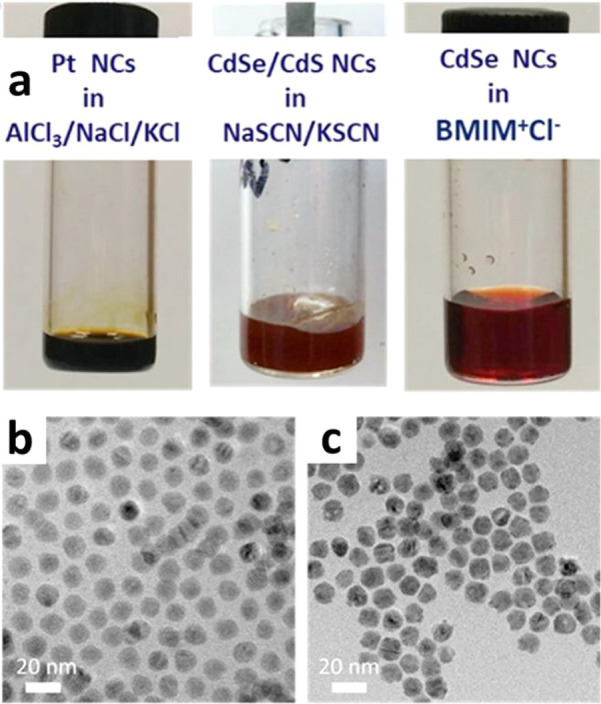

In this regard, the molten salt method is anticipated to offer colloidal stability (Figure 3) and appropriate eutectic point for the direct inorganic ligand-capped QD synthesis.60,61 Srivastava et al. suggested that a layer of surface-bound inorganic salts produces charge-density oscillations in the molten salt nearby solute particles, thereby conferring colloidal stability. A decent colloidal stability of QDs at high temperature in molten salts grants possibility that highly crystalline QDs ligated with inorganic ligands could be produced if they are synthesized directly in molten salts. Moreover, the curability of molten salt in producing highly crystalline QD lattices at high temperature shows the potential for the direct synthesis of QDs in molten salts.62

Figure 3.

(a) Representative photographs of nanocrystal colloids in molten salts and ionic liquid. (b,c) TEM images of CdSe/CdS nanocrystals (b) before dispersing in molten NaSCN/KSCN eutectic and (c) after their recovery from NaSCN/KSCN eutectic and functionalization with organic ligands. Reprinted with permission from ref (61). Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society.

3. Structural Characterization of Nanostructured Colloidal Materials

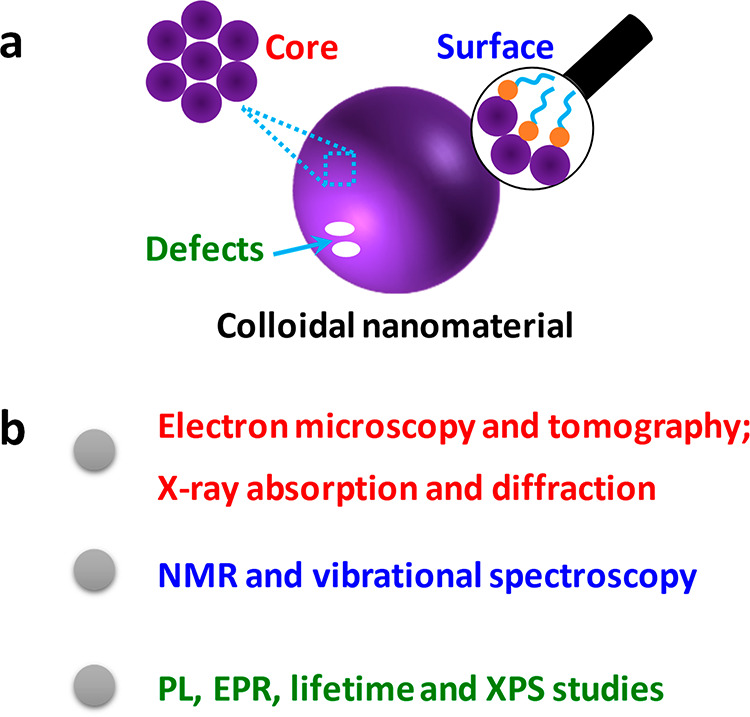

Despite immense progress of nanomaterial syntheses, the nanostructures have not been studied in greater detail. Although the importance of the atomic precision is still underconsidered,63 the atomic-level characterization of nanomaterials is essential for understanding their size- or structure-dependent properties. This section is devoted to the recent progress on the detailed structural characterization (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3. (a) Representation of the Core and Surface Structure, And Defects of the Colloidal Nanomaterials, and (b) Common Tools for Structural Characterization of Nanomaterials.

3.1. Three-Dimensional (3D) Structure

The 3D structural analysis of nanocrystals in atomic resolution is a prerequisite for the understanding and prediction of their physical properties.64 The nanoclusters composed of tens to hundreds of atoms can be characterized at the atomic level by solving their single-crystal X-ray diffraction pattern and density functional calculation. Due to intrinsic limitations, the structure characterization of nanocrystals composed of thousands of atoms is still challenging. The 3D structure of nanocrystals may be identified by the technologies based on electron microscopy, such as electron tomography and single-particle reconstruction. Electron tomography is the reconstruction of structures from a tilt series of transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images, but structural deformation may occur during the observation, as the setup requires high vacuum condition. Single-particle reconstruction based on cryo-TEM builds the atom-level structure from a number of 2D images of particles.65 However, single-particle reconstruction cannot be universally used because it requires the assumption of the identical structure of all particles, which is improper for usual nanocrystals.64,66−72

Recently, Kim et al.64 obtained the 3D density maps of eight platinum nanoparticles created from a single batch of colloidal synthesis. They reported “Brownian one particle reconstruction” method, which extends the previous work of 3D structure identification of nanoparticles by graphene liquid cell (3D SINGLE). As a result, they obtained a 3D atomic arrangement of eight individual Pt nanocrystals from the same synthetic batch. Interestingly, Pt particles have structural heterogeneity such as single-crystallinity, lattice distortion, and dislocation. The origin of high catalytic performance of Pt nanocrystals is strongly supported by structure and strain analysis, because the lattice expansion occurs near domain boundaries, dislocation edges, and surfaces.

Because of the difficulty in distinguishing different elements in TEM images, the atomic structure of multielement nanocrystals has not yet been analyzed by the referred direct electron microscopic techniques. Further development of electron microscopy and integration methods with other related characterization techniques will potentially elucidate the atomic arrangement and the origin of physical property for a wide range of nanocrystals.

3.2. Surface Structure

The importance of the surface structure of nanomaterials cannot be overstated, since the surface chemistry is a key enabler for potential applications.73 However, there is no technique for reconstructing the capping layer of nanocrystals at the atomic level. Instead, a suite of methods should be applied to obtain additional information about the nanocrystal–ligand bonding, capping-layer structure, and interactions between surface ligands and the surrounding environment.25

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is a representative method for characterizing ligands bound to the surface by tracking the fingerprints of spin-active nuclei (1H, 13C, 31P, etc.). For example, the dynamic change of ligands at the nanocrystal surface induced by different ligands or washing process can be readily tracked using NMR spectroscopy.74,75 Apart from the usual inorganic–organic interfaces, heavy-nucleus NMR (such as 119Sn) is useful to study nanocrystals stabilized with inorganic ligands.58,76 Notably, surface-bound ligands limit the use of traditional 1D NMR for nanocrystal surface analysis, because the NMR peak broadens by dipolar coupling effects. By correlating the diffusion coefficient with each resonant peak, diffusion-ordered spectroscopy is able to separate the signal of surface-bound ligand molecules from that of free ligand molecules. While the solid-state NMR (SSNMR) spectroscopy has great potential in analyzing the surface of nanocrystals, poor sensitivity precludes its regular use. Interestingly, the signal intensities can be enhanced by several folds through dynamic nuclear polarization surface enhanced NMR spectroscopy (DNP SENS).77,78 The DNP-SSNMR was used to gain insights into the surface structure of plate- and spheroidal-shaped zinc blende CdSe nanocrystals ligated by carboxylic acids.78 Various Cd coordination environments, such as CdSe3O, CdSe2O2, and CdSeO3, were identified, with the oxygen atoms having originated from the carboxylate ligands. The stoichiometries of the major Cd and Se surface species were established to be CdSe2O2 and SeCd4, respectively. Furthermore, the NMR results revealed that the surface of the spheroidal CdSe nanocrystals was mainly composed of {100} facets.

The characterization of the inorganic fraction on the surface of the colloidal nanocrystals is also very important due to its critical roles in the surface reactions, including catalysis. TEM could be a powerful tool to study changes in the surface structure under realistic conditions. Park et al. used liquid cell TEM to study facet-dependent redox-sensitivity during the etching of the ceria-based nanocrystals.79 Facet-dependent etching kinetics revealed that {100} and {111} faces show reduction and oxidation, respectively. The contribution of the predominant facet is found to be increased with the increase of the etching reactivity under each redox condition.

3.3. Defects

Crystalline materials may have imperfection in their structure, such as point, line, and planar defects. For nanomaterials with small dimensions, the defects can easily be formed on the surface or in the core during the formation and further processes, thereby significantly affecting the physicochemical properties of nanomaterials. High-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM), Raman spectroscopy, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), extended X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS), and time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) have been used to characterize the defects in nanomaterials. Recently, our group reported the synthesis of heterostructure of CeO2/Mn3O4 with enhanced antioxidant catalytic activity compared to CeO2 or Mn3O4 nanoparticles.80 The formation of a strained Mn3O4 layer and the increase in the number of oxygen vacancies in the CeO2 were demonstrated as the key factors for better activity. HAADF-STEM was used to analyze the lattice structure of the heterostructure of CeO2/Mn3O4. Although the core CeO2 structure was mostly preserved, the distortion and lattice mismatch of the heterostructure could be directly proven by HAADF-STEM images and corresponding fast Fourier transform images. The increase in oxygen defects and the structural distortion were evidenced by Raman spectroscopy and XPS.

Furthermore, the precise control of the heteroepitaxy of colloidal polyhedral nanocrystals is found to facilitate the growth of organized grains, resulting in the uniform defects associated with the grain boundaries (GB defects).81 Such topological GB defects are well-known to dramatically influence the various properties of colloidal nanocrystals, including electrical, magnetic, optical, mechanical, and chemical properties.82,83 Unfortunately, typical uncontrolled sizes and shapes of grains limit the experimental understanding of the role of GB defects in the properties of nanocrystals. Oh et al.81 synthesized multigrain nanocrystals containing Co3O4 nanocube core, which is shelled with Mn3O4. During the shelling, a large geometric misfit between adjacent Mn3O4 grains is observed, resulting in the tilt boundaries at the edges of the Co3O4 cube. Furthermore, important factors driving the formation of these ordered multigrain nanostructures have been identified. First, the shape of the nanocrystal core is anticipated to direct the crystallographic orientation of the shell. Second, the smaller size of the nanocrystal core as compared to the distance between the dislocations is preferred. Third, the geometric misfit strain between the grains could be enhanced with the mismatch between the symmetries of the nanocrystal core and its shell. Fourth, ligand-passivation of the shell could balance its surface energy for the formation of GB under near-equilibrium conditions. These four design principles enabled the synthesis of a wide range of multigrain nanocrystals containing distinct GB defects.

Srivastava et al. reported the detailed understanding and curing of structural defects in GaAs nanocrystals using bulk GaAs as the reference.62 Although the characteristic phonon mode of single crystal GaAs(111) wafer appears in Raman spectrum, only a broad feature is present in GaAs NCs. This is similar to the crystalline-to-amorphous transition of ion-bombarded GaAs nanocrystals, thereby showing the suppression of phonon mode. EPR sensitively detects the paramagnetic point defects in semiconductor nanocrystals. The EPR signal from as-synthesized GaAs nanocrystals shows a quartet signal designating an atom with a nuclear spin of 3/2 as the origin of splitting. Its relatively low hyperfine splitting of 190 G suggests that the spin density is localized on the vacancy. This should not be confused with interstitial Ga (640 G) or AsGa antisite (860 G) with high hyperfine splitting. Although both Ga and As atoms can dominate the spectrum, it should be noted that Ga atoms have two nonequivalent isotopes of I = 3/2 (69Ga and 71Ga), whereas As atoms have only one isotope (75As). Since the spectrum showed a single quartet signal, the authors could conclude that the vacancy in the GaAs nanocrystals is surrounded by As atoms. The decreased amplitude of As edge in GaAs nanocrystals in extended XAFS also supports the reduced coordination of As atoms in comparison with GaAs bulk materials.

One of the important subjects in nanoscience is the correlation between the structural defects and the photophysical properties of fluorescent semiconductor QDs. In general, the defects are known as harmful constituents that promote nonradiative decay rather than radiative one. Gao et al.84 reported the importance of surface stoichiometry of CdSe nanocrystals to achieve the unity radiative decay of excitons in single channel. Excess Cd or Se sites on the surface induce the long (short) lifetime channels for the excitons, thereby resulting in the reduced quantum yield of radiative decay. Larger stoichiometric nanocrystals have longer single channel lifetime, and the electron donating effect of surface ligands is critical to the decay dynamics and the quantum yield.

However, it should be noted that the single channel decay cannot be directly correlated with the high (even near unity) quantum yield. When CdS shell passivation is delicately controlled on the CdSe nanocrystals, the monoexponential decay of CdSe nanocrystals covered by 5–7 CdS monolayers changes into biexponential decay for CdSe nanocrystals with 8–11 CdS monolayers. The quantum yield that has 8–11 CdS monolayers is comparable to the highest value of CdSe nanocrystals showing monoexponential decay (near unity).85 The thicker shells reduce the overlap between a delocalized electron in the shell and a core-localized hole, thereby potentially allowing the electron to be easily trapped at the CdS surface in shallow traps. From this observation, they demonstrate that the defect-tolerant pathway can be an alternative strategy to achieve better quantum yield in addition to the well-known approach of the total elimination of defects.

Recently, InP QDs have been introduced as potential alternatives to traditional CdSe QDs for lighting device applications. Compared to CdSe, InP QDs are much more prone to oxidation because of not only indium but also phosphorus. Thus, highly efficient lighting devices based on InP QDs without oxidative defects are challenging. To analyze the defects on InP QDs, X-ray emission spectroscopy (XES) and solid-state NMR have been performed by Stein et al.86 After ZnS shelling on InP, phosphorus is much more oxidized than before shelling by XES. Solid-state 31P NMR also supports oxidized phosphorus defects with shelling by quantitative analysis. Furthermore, tracking excited-state electronic structure using transient absorption (TA) is very useful to gain insights into PLQYs and defects of QDs. TRPL data, on top of TA decay dynamics, supports extra decay pathway.85,87

So far, the atomic resolution structural characterization of nanocrystals is focused only on few noble metals such as Au and Pt or alloy (e.g., FePt) nanoparticles.64,66−72 Various intriguing multicomponent materials, such as binary and ternary materials, await characterization with atomic resolution. The complementary techniques, such as Raman spectroscopy, TRPL, and TA, would validate the analysis of the defects and facets for mesoscale nanomaterials.

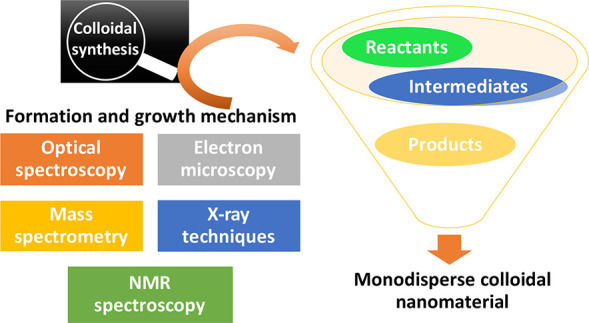

4. Mechanism Studies on Colloidal Nanomaterials

The study of nucleation and growth mechanism of the colloidal nanomaterials is a field of intense interest, because it can guide the strategic synthesis targeting specific size, morphology, and uniformity.88 Previously unexplored information on the colloidal synthesis can be elucidated using the advanced analytical techniques, such as microfluidics, mass spectrometry, in situ X-ray scattering, in situ XAFS, and liquid cell TEM (Scheme 4). The in situ techniques with high resolution can resolve not only the crystallization process but also the dynamic reactions on the surface of nanomaterials.

Scheme 4. Depiction of the Formation and Growth Mechanism Studies of Colloidal Nanomaterials by Using Spectroscopic and Microscopic Techniques.

4.1. Formation and Growth Mechanism Study

The nonclassical nucleation theory assumes spontaneous transition from amorphous to crystalline phases. However, thorough studies on dynamics are required for detailed understanding. In that sense, in situ electron microscopy could provide an unprecedented opportunity to investigate the early stage of atomic-level crystallization. Yang et al. have identified an amorphous-phase-mediated formation mechanism for Ni nanocrystals, which is different from the classical nucleation and growth model, through high-resolution in situ TEM studies.89 In the initial stages of the reaction, an amorphous phase is found to be precipitated, in which crystalline domains nucleate and subsequently form nanocrystals. Computations suggest that the amorphous precipitation of metal precursors is analogous to biomineralization, wherein the surface-induced amorphous-to-crystalline transformation is prevalent. These observations indicate that there can be several other nonclassical growth mechanisms, which need to be uncovered to understand the formation of nanocrystals.

The early stage of atomic crystallization involves structural dynamic fluctuations from disordered to crystalline state and vice versa with tracking individual Au nanocrystals for heterogeneous nucleation with in situ electron microscopy in millisecond temporal resolution.90 This process is a reversible transition rather than an irreversible one. They suggested that the structural fluctuations come from two states in atomic-level clusters with size-dependent thermodynamic stability.

Furthermore, the formation of nanocrystal superlattices has been tracked with in situ electron microscopy. Park et al.91 reported the real-time formation of 2D nanoparticle arrays in the extremely low diffusion condition. The nanoparticles mainly move by capillary forces coming from solvent drying. At the initial stage of assembly, solvents mainly condense nanoparticles into an amorphous phase. Afterward, nanoparticles crystallize into an array by local fluctuations. Their dragging mechanism matches well with simulations based on a coarse-grained lattice gas model.

The nonclassical nucleation and growth of Au nanoparticles on Pt nanoparticle surface were characterized with X-ray scattering. By in situ analysis, the very fast initial deposition of Au atoms was successfully tracked.92 Synchrotron-based time-resolved in situ small and wide-angle X-ray scattering have been used as effective tools for monitoring the formation of CdSe QDs in solution through a heat-up process at 240 °C.93 It has been shown that the lamellar structure of the Cd precursor dissolves into small micelles at 100 °C, and the first CdSe nuclei for QD formation occur around 220 °C. Moreover, a short nucleation event bursts in 30 s and decreases slowly as the concentration of nanoparticles decreases. The thermal activation of Se is found to be the rate-determining step for the formation QDs.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) is also an important tool to characterize the initial nucleation reaction and/or formation of magic-sized intermediates and their subsequent growth to nanocrystals of metal oxides, chalcogenides, and noble metals. Xie et al.94 utilized MALDI-TOF to track the initial reaction process during the formation of InP QDs. It is suggested that clusters serve as a monomer reservoir for the QD formation reaction.

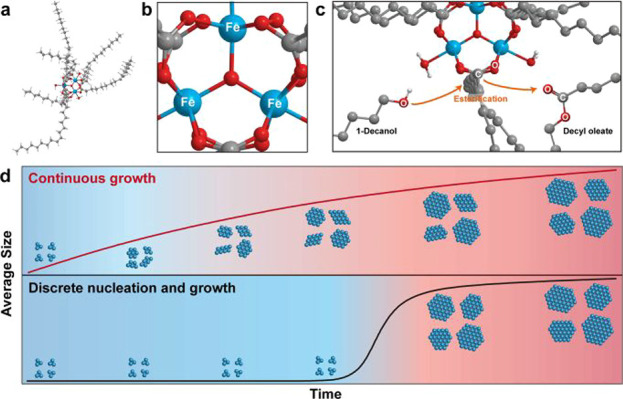

Recently, Chang et al.95 observed the continuous growth of iron oxide nanoparticles from iron-oxo clusters. MALDI MS results show that trinuclear-oxo clusters [Fe3O(oleate)6]+ are formed initially (Figure 4), which are found to serve as precursors in contrast to commonly believed mononuclear iron complexes. A detailed combinatorial analysis of the reaction products revealed that the controlled esterification of oleates, present on the surface of these clusters, with the added 1-decanol produces hydroxyl groups and decyl oleate. The highly reactive hydroxyl groups make triiron-oxo clusters to condense into intermediate iron–oxygen species containing distinct number of iron atoms, such as Fe4, Fe5, and Fe6, which further form large iron oxide clusters and finally the iron oxide nanoparticles. Notably, no distinct nucleation step is evident for the growth of iron oxide nanoparticles, while it shows only a continuous growth.

Figure 4.

(a,b) Computed structure of iron-oxo-oleate cluster [Fe3O(oleate)6]+. (c) Esterification of oleate on iron-oxo cluster with added 1-decanol. (d) Schematic of the continuous growth of iron-oxide nanoparticles (top) and the discrete nucleation and growth (bottom). A distinct nucleation step is absent in continuous growth model. Reprinted with permission from ref (95). Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society.

31P NMR could highlight the importance of stoichiometric reactants in the PbSe QD formation reaction. Evans et al.96 found that the dioctylphosphine selenide impurity in trioctylphosphine selenide is very important for the nanosized PbSe formation. Surprisingly, pure tertiary trioctylphosphine selenide turned out to be inactive with the metal carboxylate precursor and unable to produce QDs. The low concentration of dioctylphosphine selenide in trioctylphosphine selenide is responsible for the low yield in the synthesis of QDs. When stoichiometric secondary phosphine chalcogenide is used, synthetic yields reached the highest.

4.2. Reaction Mechanism at the Interface of Nanomaterials

In device and catalytic applications, reactions occur mainly at the interface of materials and reactants, which requires investigation to gain insights into the reaction mechanism. Catalyzed amide formation and esterification on the HfO2 surface could effectively exchange tightly bound carboxylate ligands into amide and/or ester.73 These reactions on the nanoparticle surface are tracked by time-resolved measurement of 1H NMR. Bound ligands show broad and weak signals, whereas noncoordinating amide and ester exhibit sharp peaks.

Although the LiO2 battery has the potential for next-generation energy storage device with the highest theoretical energy density, realization of the high discharge capacity still lags behind because of the premature passivation of the air electrode by discharge products. Redox mediators are introduced to solve the problem, but little is known about the mechanism of the fundamental electrochemical reaction of the redox mediators. Therefore, for further development of LiO2 batteries with rational design, it is required to monitor the discharge reaction of the redox mediators. Lee et al. investigated the discharge reaction of a LiO2 battery in real-time by liquid-phase TEM.97 As a result, the gradual growth upon the discharge of Li2O2 discharge product with toroidal shape was revealed in the electrolyte with the redox mediator.

5. Summary and Future Perspectives

In summary, recent advances in the colloidal synthesis and characterization of nanomaterials of semiconductors, metals, and metal oxides are discussed. The self-assembled magic-sized clusters of metal chalcogenides have been shown to exhibit highly enhanced stability, photoluminescence, and catalytic properties. The chemistry of ligand exchange and the transformation of nanocrystals are highlighted. In addition, core and surface structure characterization of nanocrystals using cutting-edge analytical tools are provided. Rapidly advancing synthetic methodologies and structural characterization technologies have improved our understanding of the nanochemistry involved in the nucleation and growth of nanocrystals. Especially, the recently developed in situ liquid-phase TEM technology enables the real-time monitoring of the formation, growth, attachment, transformation, and etching of nanomaterials. Considering the unique physicochemical properties and the scientific importance of understanding of the molecule-to-solid transition, more detailed studies need to be conducted on unexplored inorganic nanomaterials.

Despite significant advancements in the research of colloidal nanomaterials, still there are several challenges in the field, limiting their implementation in catalysis, CO2 conversion, energy production, and biomedical applications. The molecular structures of magic-sized clusters are elusive. This prevents the establishment of structure–activity relationships, which are extremely important for identifying the evolution of various properties of nanoscale materials. It may be required to consider the synthesis of colloidal nanocrystals using new sets and/or combinations of L- and X-type ligands. This may help overcome both stability and solubility to obtain single crystals of suitable quality and then to determine the molecular structure of magic-sized clusters. Introducing heteroatoms or dopants is well-known to be a promising method for realizing synergistic and enhanced optoelectronic and other properties. Currently, only Mn2+ and Co2+ have been identified as potential dopants for CdSe and ZnSe clusters. Synthetic methods need to be designed to dope metal chalcogenides with other transition metal ions, such as Cu, Ni, Fe, and others to implement them in various applications. Synthesis of nanomaterials of multielemental metal chalcogenides, similar to high entropy alloy nanomaterials, is another choice to discover new classes of functional materials.

The hetero-nanostructures of semiconductor, metal, and semiconductor–metal nanocrystals are promising candidates for photocatalytic applications. It is still challenging to synthesize these heterostructures with well-defined interfaces, enabling efficient charge transfer and product selectivity control. Using the unique reactivity of various magic-sized clusters, it may be possible to synthesize interface-controlled heterostructures that cannot be synthesized from direct or conventional methods. Similarly, the colloidal synthesis of core–shell nanomaterials is highly desirable for high photoluminescence, photostability, and catalytic properties. In addition to the colloidal approach, the solid-state synthetic methods need to be considered, because of the advantage of limited diffusion of reaction components in the solid state. The metal and semiconductor clusters are promising single source precursors, which need to be judiciously used to synthesize advanced and complex nanomaterials. The study of the chemistry of nanostructured colloidal materials is currently in the advanced stage. The use of in situ characterization techniques, such as liquid-phase TEM and X-ray scattering, is expected to become very common in the near future, which will help gain important insights into the mechanistic aspects of the reactions of nanoscale materials. We hope that these perspectives will stimulate researchers in the field and help advance the science of colloidal nanomaterials.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Research Center Program of Institute for Basic Science, Korea (IBS-R006-D1).

Author Contributions

⊥ W.B., H.C., and M.S.B. contributed equally to this work. The manuscript was written through the contribution of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

This paper was published ASAP on September 23, 2021, with incorrect replacements to both Schemes 2 and 3. The corrected version was reposted on September 24, 2021.

References

- Loiudice A.; Segura Lecina O.; Buonsanti R. Atomic Control in Multicomponent Nanomaterials: when Colloidal Chemistry Meets Atomic Layer Deposition. ACS Mater. Lett. 2020, 2, 1182–1202. 10.1021/acsmaterialslett.0c00271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strach M.; Mantella V.; Pankhurst J. R.; Iyengar P.; Loiudice A.; Das S.; Corminboeuf C.; van Beek W.; Buonsanti R. Insights into Reaction Intermediates to Predict Synthetic Pathways for Shape-Controlled Metal Nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 16312–16322. 10.1021/jacs.9b06267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J.; Buonsanti R. Colloidal Nanocrystals as Heterogeneous Catalysts for Electrochemical CO2 Conversion. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 13–25. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.8b04155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J.; Mensi M.; Oveisi E.; Mantella V.; Buonsanti R. Structural Sensitivities in Bimetallic Catalysts for Electrochemical CO2 Reduction Revealed by Ag–Cu Nanodimers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 2490–2499. 10.1021/jacs.8b12381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.; Yang J.; Kwon S. G.; Hyeon T. Nonclassical nucleation and growth of inorganic nanoparticles. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16034. 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.34. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi O.; Zakharov L. N.; Nyman M. Aqueous formation and manipulation of the iron-oxo Keggin ion. Science 2015, 347, 1359–1362. 10.1126/science.aaa4620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J.; Zhang C.; Dickson R. M. Highly Fluorescent, Water-Soluble, Size-Tunable Gold Quantum Dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 93, 077402. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.077402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudera S.; Zanella M.; Giannini C.; Rizzo A.; Li Y.; Gigli G.; Cingolani R.; Ciccarella G.; Spahl W.; Parak W. J.; Manna L. Sequential Growth of Magic-Size CdSe Nanocrystals. Adv. Mater. 2007, 19, 548–552. 10.1002/adma.200601015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Navrotsky A. Nanoscale Effects on Thermodynamics and Phase Equilibria in Oxide Systems. ChemPhysChem 2011, 12, 2207–2215. 10.1002/cphc.201100129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F.; Richards V. N.; Shields S. P.; Buhro W. E. Kinetics and Mechanisms of Aggregative Nanocrystal Growth. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 5–21. 10.1021/cm402139r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Penn R. L.; Banfield J. F. Imperfect Oriented Attachment: Dislocation Generation in Defect-Free Nanocrystals. Science 1998, 281, 969–971. 10.1126/science.281.5379.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.; Nielsen M. H.; Lee J. R. I.; Frandsen C.; Banfield J. F.; De Yoreo J. J. Direction-Specific Interactions Control Crystal Growth by Oriented Attachment. Science 2012, 336, 1014–1018. 10.1126/science.1219643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson C. B.; Nevers D. R.; Nelson A.; Hadar I.; Banin U.; Hanrath T.; Robinson R. D. Chemically reversible isomerization of inorganic clusters. Science 2019, 363, 731–735. 10.1126/science.aau9464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasuya A.; Sivamohan R.; Barnakov Y. A.; Dmitruk I. M.; Nirasawa T.; Romanyuk V. R.; Kumar V.; Mamykin S. V.; Tohji K.; Jeyadevan B.; Shinoda K.; Kudo T.; Terasaki O.; Liu Z.; Belosludov R. V.; Sundararajan V.; Kawazoe Y. Ultra-stable nanoparticles of CdSe revealed from mass spectrometry. Nat. Mater. 2004, 3, 99–102. 10.1038/nmat1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Liu Y.-H.; Zhang Y.; Wang F.; Kowalski P. J.; Rohrs H. W.; Loomis R. A.; Gross M. L.; Buhro W. E. Isolation of the Magic-Size CdSe Nanoclusters [(CdSe)13(n-octylamine)13] and [(CdSe)13(oleylamine)13]. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 6154–6157. 10.1002/anie.201202380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.; Muckel F.; Choi B. K.; Lorenz S.; Kim I. Y.; Ackermann J.; Chang H.; Czerney T.; Kale V. S.; Hwang S.-J.; Bacher G.; Hyeon T. Co2+-Doping of Magic-Sized CdSe Clusters: Structural Insights via Ligand Field Transitions. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 7350–7357. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b03627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muckel F.; Yang J.; Lorenz S.; Baek W.; Chang H.; Hyeon T.; Bacher G.; Fainblat R. Digital Doping in Magic-Sized CdSe Clusters. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 7135–7141. 10.1021/acsnano.6b03348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.; Fainblat R.; Kwon S. G.; Muckel F.; Yu J. H.; Terlinden H.; Kim B. H.; Iavarone D.; Choi M. K.; Kim I. Y.; Park I.; Hong H.-K.; Lee J.; Son J. S.; Lee Z.; Kang K.; Hwang S.-J.; Bacher G.; Hyeon T. Route to the Smallest Doped Semiconductor: Mn2+-Doped (CdSe)13 Clusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 12776–12779. 10.1021/jacs.5b07888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMer V. K.; Dinegar R. H. Theory, Production and Mechanism of Formation of Monodispersed Hydrosols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1950, 72, 4847–4854. 10.1021/ja01167a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao D.; Hao X.; Rowell N.; Kreouzis T.; Lockwood D. J.; Han S.; Fan H.; Zhang H.; Zhang C.; Jiang Y.; Zeng J.; Zhang M.; Yu K. Formation of colloidal alloy semiconductor CdTeSe magic-size clusters at room temperature. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1674. 10.1038/s41467-019-09705-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bootharaju M. S.; Baek W.; Lee S.; Chang H.; Kim J.; Hyeon T. Magic-Sized Stoichiometric II–VI Nanoclusters. Small 2021, 17, 2002067. 10.1002/smll.202002067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B.; Zhu T.; Ou M.; Rowell N.; Fan H.; Han J.; Tan L.; Dove M. T.; Ren Y.; Zuo X.; Han S.; Zeng J.; Yu K. Thermally-induced reversible structural isomerization in colloidal semiconductor CdS magic-size clusters. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2499. 10.1038/s41467-018-04842-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuer-Jungemann A.; Feliu N.; Bakaimi I.; Hamaly M.; Alkilany A.; Chakraborty I.; Masood A.; Casula M. F.; Kostopoulou A.; Oh E.; Susumu K.; Stewart M. H.; Medintz I. L.; Stratakis E.; Parak W. J.; Kanaras A. G. The Role of Ligands in the Chemical Synthesis and Applications of Inorganic Nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 4819–4880. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Peng X. Size/Shape-Controlled Synthesis of Colloidal CdSe Quantum Disks: Ligand and Temperature Effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 6578–6586. 10.1021/ja108145c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boles M. A.; Ling D.; Hyeon T.; Talapin D. V. The surface science of nanocrystals. Nat. Mater. 2016, 15, 141–153. 10.1038/nmat4526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalenko M. V.; Scheele M.; Talapin D. V. Colloidal Nanocrystals with Molecular Metal Chalcogenide Surface Ligands. Science 2009, 324, 1417–1420. 10.1126/science.1170524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedfeld M. R.; Stein J. L.; Ritchhart A.; Cossairt B. M. Conversion Reactions of Atomically Precise Semiconductor Clusters. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 2803–2810. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L.; Pickard C. J.; Yu K.; Sapelkin A.; Misquitta A. J.; Dove M. T. Structures of CdSe and CdS Nanoclusters from Ab Initio Random Structure Searching. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 29370–29378. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b05763. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gary D. C.; Flowers S. E.; Kaminsky W.; Petrone A.; Li X.; Cossairt B. M. Single-Crystal and Electronic Structure of a 1.3 nm Indium Phosphide Nanocluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 1510–1513. 10.1021/jacs.5b13214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palencia C.; Yu K.; Boldt K. The Future of Colloidal Semiconductor Magic-Size Clusters. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 1227–1235. 10.1021/acsnano.0c00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedfeld M. R.; Stein J. L.; Cossairt B. M. Main-Group-Semiconductor Cluster Molecules as Synthetic Intermediates to Nanostructures. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 8689–8697. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b00291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son J. S.; Wen X.-D.; Joo J.; Chae J.; Baek S.-i.; Park K.; Kim J. H.; An K.; Yu J. H.; Kwon S. G.; Choi S.-H.; Wang Z.; Kim Y.-W.; Kuk Y.; Hoffmann R.; Hyeon T. Large-Scale Soft Colloidal Template Synthesis of 1.4 nm Thick CdSe Nanosheets. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 6861–6864. 10.1002/anie.200902791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.-H.; Wang F.; Wang Y.; Gibbons P. C.; Buhro W. E. Lamellar Assembly of Cadmium Selenide Nanoclusters into Quantum Belts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 17005–17013. 10.1021/ja206776g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.; Muckel F.; Baek W.; Fainblat R.; Chang H.; Bacher G.; Hyeon T. Chemical Synthesis, Doping, and Transformation of Magic-Sized Semiconductor Alloy Nanoclusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 6761–6770. 10.1021/jacs.7b02953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Zhang Y.; Wang F.; Giblin D. E.; Hoy J.; Rohrs H. W.; Loomis R. A.; Buhro W. E. The Magic-Size Nanocluster (CdSe)34 as a Low-Temperature Nucleant for Cadmium Selenide Nanocrystals; Room-Temperature Growth of Crystalline Quantum Platelets. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 2233–2243. 10.1021/cm404068e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Zhou Y.; Zhang Y.; Buhro W. E. Magic-Size II–VI Nanoclusters as Synthons for Flat Colloidal Nanocrystals. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 1165–1177. 10.1021/ic502637q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J. H.; Liu X.; Kweon K. E.; Joo J.; Park J.; Ko K.-T.; Lee D. W.; Shen S.; Tivakornsasithorn K.; Son J. S.; Park J.-H.; Kim Y.-W.; Hwang G. S.; Dobrowolska M.; Furdyna J. K.; Hyeon T. Giant Zeeman splitting in nucleation-controlled doped CdSe:Mn2+ quantum nanoribbons. Nat. Mater. 2010, 9, 47–53. 10.1038/nmat2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek W.; Bootharaju M. S.; Walsh K. M.; Lee S.; Gamelin D. R.; Hyeon T. Highly luminescent and catalytically active suprastructures of magic-sized semiconductor nanoclusters. Nat. Mater. 2021, 20, 650–657. 10.1038/s41563-020-00880-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boles M. A.; Engel M.; Talapin D. V. Self-Assembly of Colloidal Nanocrystals: From Intricate Structures to Functional Materials. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 11220–11289. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevchenko E. V.; Talapin D. V.; Murray C. B.; O’Brien S. Structural Characterization of Self-Assembled Multifunctional Binary Nanoparticle Superlattices. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 3620–3637. 10.1021/ja0564261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainò G.; Becker M. A.; Bodnarchuk M. I.; Mahrt R. F.; Kovalenko M. V.; Stöferle T. Superfluorescence from lead halide perovskite quantum dot superlattices. Nature 2018, 563, 671–675. 10.1038/s41586-018-0683-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J. A.; Wu C.; Bao K.; Bao J.; Bardhan R.; Halas N. J.; Manoharan V. N.; Nordlander P.; Shvets G.; Capasso F. Self-Assembled Plasmonic Nanoparticle Clusters. Science 2010, 328, 1135–1138. 10.1126/science.1187949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett C. A.; Helal A.; Al-Maythalony B. A.; Yamani Z. H.; Cordova K. E.; Yaghi O. M. The chemistry of metal–organic frameworks for CO2 capture, regeneration and conversion. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017, 2, 17045. 10.1038/natrevmats.2017.45. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R.-W.; Wei Y.-S.; Dong X.-Y.; Wu X.-H.; Du C.-X.; Zang S.-Q.; Mak T. C. W. Hypersensitive dual-function luminescence switching of a silver-chalcogenolate cluster-based metal–organic framework. Nat. Chem. 2017, 9, 689–697. 10.1038/nchem.2718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane R. J.; Lee B.; Jones M. R.; Harris N.; Schatz G. C.; Mirkin C. A. Nanoparticle Superlattice Engineering with DNA. Science 2011, 334, 204–208. 10.1126/science.1210493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.; Astruc D. State of the Art and Prospects in Metal–Organic Framework (MOF)-Based and MOF-Derived Nanocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 1438–1511. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H.; Karan N. S.; Shin K.; Bootharaju M. S.; Nah S.; Chae S. I.; Baek W.; Lee S.; Kim J.; Son Y. J.; Kang T.; Ko G.; Kwon S.-H.; Hyeon T. Highly Fluorescent Gold Cluster Assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 326–334. 10.1021/jacs.0c10907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bootharaju M. S.; Lee S.; Deng G.; Chang H.; Baek W.; Hyeon T. High photoluminescence from self-assembled Ag2Cl2(dppe)2 clusters through metallophilic interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 155, 014307. 10.1063/5.0057356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan P.; Zhang R.; Selenius E.; Ruan P.; Yao Y.; Zhou Y.; Malola S.; Häkkinen H.; Teo B. K.; Cao Y.; Zheng N. Solvent-mediated assembly of atom-precise gold–silver nanoclusters to semiconducting one-dimensional materials. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2229. 10.1038/s41467-020-16062-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stranks S. D.; Eperon G. E.; Grancini G.; Menelaou C.; Alcocer M. J. P.; Leijtens T.; Herz L. M.; Petrozza A.; Snaith H. J. Electron-Hole Diffusion Lengths Exceeding 1 Micrometer in an Organometal Trihalide Perovskite Absorber. Science 2013, 342, 341–344. 10.1126/science.1243982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho T.; Takahashi E.; Hirata M.; Yamaguchi N.; Teraji T.; Matsuda K.; Takeuchi A.; Kohagura J.; Yatsu K.; Tamano T.; Kondoh T.; Aoki S.; Zhang X. W.; Maezawa H.; Miyoshi S. Evidence against existing x-ray-energy response theories for silicon-surface-barrier semiconductor detectors. Phys. Rev. A: At., Mol., Opt. Phys. 1992, 46, R3024–R3027. 10.1103/PhysRevA.46.R3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang C.-H. M.; Brown P. R.; Bulović V.; Bawendi M. G. Improved performance and stability in quantum dot solar cells through band alignment engineering. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 796–801. 10.1038/nmat3984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q.; Yun H. J.; Liu W.; Song H.-J.; Makarov N. S.; Isaienko O.; Nakotte T.; Chen G.; Luo H.; Klimov V. I.; Pietryga J. M. Phase-Transfer Ligand Exchange of Lead Chalcogenide Quantum Dots for Direct Deposition of Thick, Highly Conductive Films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 6644–6653. 10.1021/jacs.7b01327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.; Xiong K.; Wang K.; Liang G.; Li M.-Y.; Tang H.; Yang X.; Huang Z.; Lian L.; Tan M.; Wang K.; Gao L.; Song H.; Zhang D.; Gao J.; Lan X.; Tang J.; Zhang J. Efficiently Passivated PbSe Quantum Dot Solids for Infrared Photovoltaics. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 3376–3386. 10.1021/acsnano.0c10373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.; Choi M.-J.; Sharma G.; Biondi M.; Chen B.; Baek S.-W.; Najarian A. M.; Vafaie M.; Wicks J.; Sagar L. K.; Hoogland S.; de Arquer F. P. G.; Voznyy O.; Sargent E. H. Orthogonal colloidal quantum dot inks enable efficient multilayer optoelectronic devices. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4814. 10.1038/s41467-020-18655-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierick R.; Van den Broeck F.; De Nolf K.; Zhao Q.; Vantomme A.; Martins J. C.; Hens Z. Surface Chemistry of CuInS2 Colloidal Nanocrystals, Tight Binding of L-Type Ligands. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 5950–5957. 10.1021/cm502687p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Kergommeaux A.; Fiore A.; Faure-Vincent J.; Chandezon F.; Pron A.; de Bettignies R.; Reiss P. Highly conductive CuInSe2 nanocrystals with inorganic surface ligands. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2012, 136, 877–882. 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2012.08.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalenko M. V.; Bodnarchuk M. I.; Zaumseil J.; Lee J.-S.; Talapin D. V. Expanding the Chemical Versatility of Colloidal Nanocrystals Capped with Molecular Metal Chalcogenide Ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 10085–10092. 10.1021/ja1024832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Liu Z.; Huo N.; Li F.; Gu M.; Ling X.; Zhang Y.; Lu K.; Han L.; Fang H.; Shulga A. G.; Xue Y.; Zhou S.; Yang F.; Tang X.; Zheng J.; Antonietta Loi M.; Konstantatos G.; Ma W. Room-temperature direct synthesis of semi-conductive PbS nanocrystal inks for optoelectronic applications. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5136. 10.1038/s41467-019-13158-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.; Dasbiswas K.; Ludwig N. B.; Han G.; Lee B.; Vaikuntanathan S.; Talapin D. V. Stable colloids in molten inorganic salts. Nature 2017, 542, 328–331. 10.1038/nature21041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamysbayev V.; Srivastava V.; Ludwig N. B.; Borkiewicz O. J.; Zhang H.; Ilavsky J.; Lee B.; Chapman K. W.; Vaikuntanathan S.; Talapin D. V. Nanocrystals in Molten Salts and Ionic Liquids: Experimental Observation of Ionic Correlations Extending beyond the Debye Length. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 5760–5770. 10.1021/acsnano.9b01292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava V.; Liu W.; Janke E. M.; Kamysbayev V.; Filatov A. S.; Sun C.-J.; Lee B.; Rajh T.; Schaller R. D.; Talapin D. V. Understanding and Curing Structural Defects in Colloidal GaAs Nanocrystals. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 2094–2101. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b00481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hens Z.; De Roo J. Atomically Precise Nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 15627–15637. 10.1021/jacs.0c05082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B. H.; Heo J.; Kim S.; Reboul C. F.; Chun H.; Kang D.; Bae H.; Hyun H.; Lim J.; Lee H.; Han B.; Hyeon T.; Alivisatos A. P.; Ercius P.; Elmlund H.; Park J. Critical differences in 3D atomic structure of individual ligand-protected nanocrystals in solution. Science 2020, 368, 60–67. 10.1126/science.aax3233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B. H.; Yang J.; Lee D.; Choi B. K.; Hyeon T.; Park J. Liquid-Phase Transmission Electron Microscopy for Studying Colloidal Inorganic Nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1703316. 10.1002/adma.201703316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.; Elmlund H.; Ercius P.; Yuk J. M.; Limmer D. T.; Chen Q.; Kim K.; Han S. H.; Weitz D. A.; Zettl A.; Alivisatos A. P. 3D structure of individual nanocrystals in solution by electron microscopy. Science 2015, 349, 290–295. 10.1126/science.aab1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu R.; Chen C.-C.; Wu L.; Scott M. C.; Theis W.; Ophus C.; Bartels M.; Yang Y.; Ramezani-Dakhel H.; Sawaya M. R.; Heinz H.; Marks L. D.; Ercius P.; Miao J. Three-dimensional coordinates of individual atoms in materials revealed by electron tomography. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 1099–1103. 10.1038/nmat4426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.; Chen C.-C.; Scott M. C.; Ophus C.; Xu R.; Pryor A.; Wu L.; Sun F.; Theis W.; Zhou J.; Eisenbach M.; Kent P. R. C.; Sabirianov R. F.; Zeng H.; Ercius P.; Miao J. Deciphering chemical order/disorder and material properties at the single-atom level. Nature 2017, 542, 75–79. 10.1038/nature21042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goris B.; Bals S.; Van den Broek W.; Carbó-Argibay E.; Gómez-Graña S.; Liz-Marzán L. M.; Van Tendeloo G. Atomic-scale determination of surface facets in gold nanorods. Nat. Mater. 2012, 11, 930–935. 10.1038/nmat3462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao J.; Ercius P.; Billinge S. J. L. Atomic electron tomography: 3D structures without crystals. Science 2016, 353, aaf2157. 10.1126/science.aaf2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartesaghi A.; Sprechmann P.; Liu J.; Randall G.; Sapiro G.; Subramaniam S. Classification and 3D averaging with missing wedge correction in biological electron tomography. J. Struct. Biol. 2008, 162, 436–450. 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y. Single-Particle Cryo-EM at Crystallographic Resolution. Cell 2015, 161, 450–457. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Roo J.; Van Driessche I.; Martins J. C.; Hens Z. Colloidal metal oxide nanocrystal catalysis by sustained chemically driven ligand displacement. Nat. Mater. 2016, 15, 517–521. 10.1038/nmat4554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson N. C.; Owen J. S. Soluble, Chloride-Terminated CdSe Nanocrystals: Ligand Exchange Monitored by 1H and 31P NMR Spectroscopy. Chem. Mater. 2013, 25, 69–76. 10.1021/cm303219a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng B.; Palui G.; Zhang C.; Zhan N.; Wang W.; Ji X.; Chen B.; Mattoussi H. Characterization of the Ligand Capping of Hydrophobic CdSe–ZnS Quantum Dots Using NMR Spectroscopy. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 225–238. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b04204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Protesescu L.; Nachtegaal M.; Voznyy O.; Borovinskaya O.; Rossini A. J.; Emsley L.; Copéret C.; Günther D.; Sargent E. H.; Kovalenko M. V. Atomistic Description of Thiostannate-Capped CdSe Nanocrystals: Retention of Four-Coordinate SnS4 Motif and Preservation of Cd-Rich Stoichiometry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 1862–1874. 10.1021/ja510862c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanrahan M. P.; Chen Y.; Blome-Fernández R.; Stein J. L.; Pach G. F.; Adamson M. A. S.; Neale N. R.; Cossairt B. M.; Vela J.; Rossini A. J. Probing the Surface Structure of Semiconductor Nanoparticles by DNP SENS with Dielectric Support Materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 15532–15546. 10.1021/jacs.9b05509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Dorn R. W.; Hanrahan M. P.; Wei L.; Blome-Fernández R.; Medina-Gonzalez A. M.; Adamson M. A. S.; Flintgruber A. H.; Vela J.; Rossini A. J. Revealing the Surface Structure of CdSe Nanocrystals by Dynamic Nuclear Polarization-Enhanced 77Se and 113Cd Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 8747–8760. 10.1021/jacs.1c03162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung J.; Choi B. K.; Kim B.; Kim B. H.; Kim J.; Lee D.; Kim S.; Kang K.; Hyeon T.; Park J. Redox-Sensitive Facet Dependency in Etching of Ceria Nanocrystals Directly Observed by Liquid Cell TEM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 18395–18399. 10.1021/jacs.9b09508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S. I.; Lee S.-w.; Cho M. G.; Yoo J. M.; Oh M. H.; Jeong B.; Kim D.; Park O. K.; Kim J.; Namkoong E.; Jo J.; Lee N.; Lim C.; Soh M.; Sung Y.-E.; Yoo J.; Park K.; Hyeon T. Epitaxially Strained CeO2/Mn3O4 Nanocrystals as an Enhanced Antioxidant for Radioprotection. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2001566. 10.1002/adma.202001566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh M. H.; Cho M. G.; Chung D. Y.; Park I.; Kwon Y. P.; Ophus C.; Kim D.; Kim M. G.; Jeong B.; Gu X. W.; Jo J.; Yoo J. M.; Hong J.; McMains S.; Kang K.; Sung Y.-E.; Alivisatos A. P.; Hyeon T. Design and synthesis of multigrain nanocrystals via geometric misfit strain. Nature 2020, 577, 359–363. 10.1038/s41586-019-1899-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R. W.; Thomas G. J. Grain boundaries in nanophase materials. Ultramicroscopy 1992, 40, 376–384. 10.1016/0304-3991(92)90135-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ovid’ko I. A. Deformation of Nanostructures. Science 2002, 295, 2386. 10.1126/science.1071064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y.; Peng X. Photogenerated Excitons in Plain Core CdSe Nanocrystals with Unity Radiative Decay in Single Channel: The Effects of Surface and Ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 4230–4235. 10.1021/jacs.5b01314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanifi D. A.; Bronstein N. D.; Koscher B. A.; Nett Z.; Swabeck J. K.; Takano K.; Schwartzberg A. M.; Maserati L.; Vandewal K.; van de Burgt Y.; Salleo A.; Alivisatos A. P. Redefining near-unity luminescence in quantum dots with photothermal threshold quantum yield. Science 2019, 363, 1199–1202. 10.1126/science.aat3803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein J. L.; Holden W. M.; Venkatesh A.; Mundy M. E.; Rossini A. J.; Seidler G. T.; Cossairt B. M. Probing Surface Defects of InP Quantum Dots Using Phosphorus Kα and Kβ X-ray Emission Spectroscopy. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 6377–6388. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.8b02590. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi G.; Geuchies J. J.; van der Stam W.; du Fossé I.; Brynjarsson B.; Kirkwood N.; Kinge S.; Siebbeles L. D. A.; Houtepen A. J. Spectroscopic Evidence for the Contribution of Holes to the Bleach of Cd-Chalcogenide Quantum Dots. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 3002–3010. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanh N. T. K.; Maclean N.; Mahiddine S. Mechanisms of Nucleation and Growth of Nanoparticles in Solution. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 7610–7630. 10.1021/cr400544s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.; Koo J.; Kim S.; Jeon S.; Choi B. K.; Kwon S.; Kim J.; Kim B. H.; Lee W. C.; Lee W. B.; Lee H.; Hyeon T.; Ercius P.; Park J. Amorphous-Phase-Mediated Crystallization of Ni Nanocrystals Revealed by High-Resolution Liquid-Phase Electron Microscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 763–768. 10.1021/jacs.8b11972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon S.; Heo T.; Hwang S.-Y.; Ciston J.; Bustillo K. C.; Reed B. W.; Ham J.; Kang S.; Kim S.; Lim J.; Lim K.; Kim J. S.; Kang M.-H.; Bloom R. S.; Hong S.; Kim K.; Zettl A.; Kim W. Y.; Ercius P.; Park J.; Lee W. C. Reversible disorder-order transitions in atomic crystal nucleation. Science 2021, 371, 498–503. 10.1126/science.aaz7555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.; Zheng H.; Lee W. C.; Geissler P. L.; Rabani E.; Alivisatos A. P. Direct Observation of Nanoparticle Superlattice Formation by Using Liquid Cell Transmission Electron Microscopy. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 2078–2085. 10.1021/nn203837m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon S. G.; Krylova G.; Phillips P. J.; Klie R. F.; Chattopadhyay S.; Shibata T.; Bunel E. E.; Liu Y.; Prakapenka V. B.; Lee B.; Shevchenko E. V. Heterogeneous nucleation and shape transformation of multicomponent metallic nanostructures. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 215–223. 10.1038/nmat4115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abécassis B.; Bouet C.; Garnero C.; Constantin D.; Lequeux N.; Ithurria S.; Dubertret B.; Pauw B. R.; Pontoni D. Real-Time in Situ Probing of High-Temperature Quantum Dots Solution Synthesis. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 2620–2626. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b00199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L.; Shen Y.; Franke D.; Sebastián V.; Bawendi M. G.; Jensen K. F. Characterization of Indium Phosphide Quantum Dot Growth Intermediates Using MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 13469–13472. 10.1021/jacs.6b06468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H.; Kim B. H.; Jeong H. Y.; Moon J. H.; Park M.; Shin K.; Chae S. I.; Lee J.; Kang T.; Choi B. K.; Yang J.; Bootharaju M. S.; Song H.; An S. H.; Park K. M.; Oh J. Y.; Lee H.; Kim M. S.; Park J.; Hyeon T. Molecular-Level Understanding of Continuous Growth from Iron-Oxo Clusters to Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 7037–7045. 10.1021/jacs.9b01670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans C. M.; Evans M. E.; Krauss T. D. Mysteries of TOPSe Revealed: Insights into Quantum Dot Nucleation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 10973–10975. 10.1021/ja103805s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D.; Park H.; Ko Y.; Park H.; Hyeon T.; Kang K.; Park J. Direct Observation of Redox Mediator-Assisted Solution-Phase Discharging of Li–O2 Battery by Liquid-Phase Transmission Electron Microscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 8047–8052. 10.1021/jacs.9b02332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]