Abstract

Objective:

To compare the degree of debris and friction of conventional and self-ligating orthodontic brackets before and after clinical use.

Materials and Methods:

Two sets of three conventional and self-ligating brackets were bonded from the first molar to the first premolar in eight individuals, for a total of 16 sets per type of brackets. A passive segment of 0.019 × 0.025-inch stainless steel archwire was inserted into each group of brackets. Frictional force and debris level were evaluated as received and after 8 weeks of intraoral exposure. Two-way analysis of variance and Wilcoxon signed-rank test were applied at P < .05.

Results:

After the intraoral exposure, there was a significant increase of debris accumulation in both systems of brackets (P < .05). However, the self-ligating brackets showed a higher amount of debris compared with the conventional brackets. The frictional force in conventional brackets was significantly higher when compared with self-ligating brackets before clinical use (P < .001). Clinical exposure for 8 weeks provided a significant increase of friction (P < .001) on both systems. In the self-ligating system, the mean of friction increase was 0.21 N (191%), while 0.52 N (47.2%) was observed for the conventional system.

Conclusion:

Self-ligating and conventional brackets, when exposed to the intraoral environment, showed a significant increase in frictional force during the sliding mechanics. Debris accumulation was higher for the self-ligating system.

Keywords: Orthodontic brackets, Self-ligating brackets, Friction

INTRODUCTION

Friction is a force that resists motion between objects in contact, and it is tangential to the common boundary between them.1 The friction between the orthodontic bracket and the archwire can cause more than 50% loss of orthodontic force initially applied, resulting in decreased or even an inhibition of desired tooth movement.1–5 However, during the orthodontic treatment, friction is always present; therefore, it is desirable to have a level of friction as low as possible.6

Several factors can determine the friction resistance between the archwire and orthodontic brackets such as the angulations between the wire and bracket,7,8 the size and materials of the archwire,9,10 the ligation bracket system,11–13 saliva,14,15 and the width and materials of the brackets.2,16 Furthermore, studies have shown that debris accumulation on the wire surface increases roughness and generates higher levels of friction.17,18

Self-ligating brackets were designed to eliminate elastomers and steel ligature wires based on the concept that this system would create an environment with lower friction, allowing a more efficient mechanical sliding that might reduce treatment time.19 Although the friction produced by self-ligating brackets is a controversial issue,20 some in vitro studies have reported a significant reduction in friction when as-received self-ligating brackets are compared with conventional brackets.21 Such friction reduction does not seem to have a significant influence on treatment time in orthodontics.22–24 This different behavior between clinical and in vitro studies could be related to the effects of intraoral aging on orthodontic materials.14 Meanwhile, recent studies have reported that conventional brackets favor a lower aggregation of microorganisms when compared with self-ligating brackets.25,26 Despite the existence of some information about the effect of intraoral exposure on friction and accumulation of debris in orthodontic wires,17,18 there is no information about the changes produced by intraoral exposure regarding the set of bracket and wires. Our aim is to evaluate debris and friction of conventional and self-ligating orthodontic brackets before and after clinical use.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee and Research to Science Health Institute of Brazilian Federal University of Pará under number 039773/2012.

The sample size was calculated to observe the differences between as-received brackets (T0) and after 8 weeks of clinical use (T1). A power of 80% was assumed to detect a difference of 0.5 N of force, with standard deviations of 0.3 (T0) and 0.6 (T1) and a bilateral alpha level of 5%. Standard deviations were determined by a pilot study involving six pairs of as-received and clinical exposed brackets obtained from three patients. The sample size was determined to be n = 8 (T0) and n = 16 (T1), as the variance was doubled after clinical use.17

The effects of intraoral exposure on friction were examined in eight adults (four men and four women). The four hemi-arches of each patient received a set of three brackets from the first molar to the first premolar (32 hemi-arches). Groups were randomized (Figure 1). In two hemi-arches, from each patient, the conventional metallic bracket slots of 0.022 × 0.028 inches (Kirium LINE-Abzil, São José dos Campos, SP, Brazil) were bonded; the other ones received self-ligating bracket slots of 0.022 × 0.028 inches (PORTIA-Abzil, São José dos Campos, SP, Brazil). Both were Roth prescriptions. A straight segment of stainless steel wire of 0.019 × 0.025 inches (Unitek, Monrovia, Calif) was inserted into the bracket. For the conventional ligation group (n = 16), the brackets were tied with elastic ligature (diameter of 0.120 inches; Unicycles, MASEL, Carlsbad, Calif). The sets of brackets and wires remained in the oral environment for 8 weeks (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Intraoral view of randomized split-mouth grouping.

We used brackets bonded on the second premolar since this is a bracket in which the wire slides during retraction mechanics.

Debris Accumulation

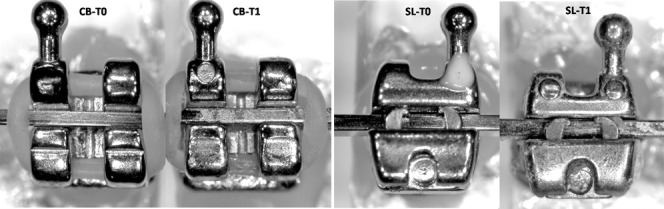

Images were obtained through a magnifying lens of 20× (Model MV 200 µm, Miviewcap, Shenzhen, China) to evaluate debris accumulation on the bracket and wire set before and after clinical use (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Images used to determine debris score before (T0) and after clinical use.

The amount of debris was scored by a single examiner according to a previous published method.17,18 Assessment of the amount of debris on the bracket surface was performed by a single examiner. The following scores were used: 0 = total absence of debris; 1 = some debris, involving less than one-fourth of the image analyzed; 2 = moderate presence of debris involving one-fourth to three-fourths of the image; and 4 = presence of a large amount of debris involving more than three-fourths of the image examined.

For the analysis of error, two blinded readings of each bracket were performed with an interval of 1 week. Reliability was evaluated using Spearman's correlation test at P < .05.

Scoring the level of debris before and after clinical use was performed for all 32 brackets, 16 conventional and 16 self-ligating, and compared through a Wilcoxon signed-rank test at P < .05.

Friction Test

To evaluate the influence of bracket deformation caused by debonding, 10 as-received brackets (5 conventional and 5 self-ligating) were bonded in human premolars and then removed using thin cutting pliers (Pin and Ligature Cutter-Standard, Straight-, Orthopli Corporation, Philadelphia, Penn). Friction was evaluated in both groups, before and after debonding, and compared through one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

The friction test was performed using acrylic plates (area = 4 × 5.5 cm and thicknesses = 0.5 cm) according to a previous published methodology.17,22 Only second premolar brackets of each hemi-arch and the entire intraoral exposed wire were bonded in individual plates. Each bracket was bonded with 4 mm between and 2 mm from the extremities of each plate. The acrylic plates containing brackets and wire segments were fixed in the universal testing machine (EMIC DL 2000, São José dos Pinhais, Brazil) and positioned at a 90° angle relative to the ground. The machine was enabled and the upper grip slid at a speed of 0.5 mm/min for a distance of 5 mm. The mean dynamic frictional force was measured in Newtons (N).

Normal distribution was checked through D'Agostino statistical test. Two-way ANOVA was used to observe differences between T0 × T1 and the influence of the type of bracket ligation (conventional × self-ligating). All statistics were analyzed at P < .05 using BioEstat 5.3 software (Mamirauá's Institute for Sustainable Development, Belém, PA, Brazil).

RESULTS

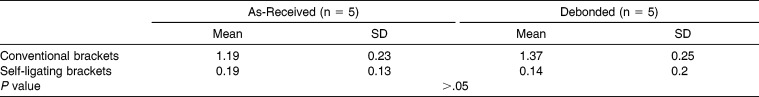

No significant difference in friction level was observed when as-received and debonded brackets, without intraoral aging, were compared. This finding showed that the technique used to debond brackets did not cause a significant increase in frictional force (P < .05; Table 1).

Table 1.

Friction Mean, Standard Deviation (SD), and P Value (ANOVA) for As-Received and New Debonded Brackets

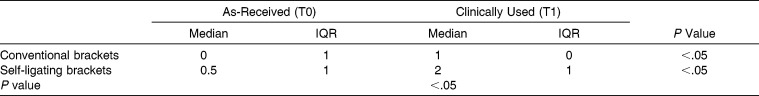

The microscopic analysis of debris accumulation after intraoral exposure showed a significant increase in debris residues on both conventional and self-ligating bracket systems (P < .05). Moreover, self-ligating brackets demonstrated a doubled increase of debris amount when compared with conventional brackets (Table 2).

Table 2.

Median, Interquartile Range (IQR), and P Value (Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test) for Debris Score in As-Received (T0) and Clinical Exposed Brackets (T1)

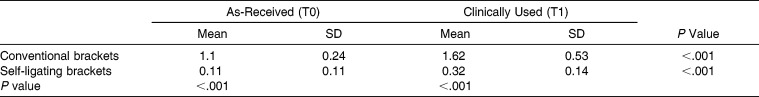

The mean frictional force to conventional brackets, before clinical use, was 1.1 N (SD = 0.24), while the mean friction for self-ligating brackets was significantly lower (P < .001), with a mean of 0.11 N (SD = 0.11). After intraoral exposition for 8 weeks, there was a significant increase in the level of friction for both systems of brackets (P < .001; Table 3). Compared with baseline, the increase in friction was 0.52 N (47.3%) higher for conventional brackets and 0.21 N (191%) for self-ligating system. The interaction among variables was also significant (P < .05).

Table 3.

Friction Mean, Standard Deviation (SD), and P Value (Two-Way ANOVA) for As-Received (T0) and Clinical Exposed Brackets (T2)

DISCUSSION

The assessment of material properties after orthodontic clinical use is routinely reported as a necessity,4,27 but few studies have investigated the properties of orthodontic materials after clinical aging. Some studies have evaluated the effect of clinical use on friction17,18,27 and bacterial aggregation25,26; however, there are no published papers comparing friction of conventional and self-ligating brackets after intraoral exposure.

Recent studies have demonstrated that self-ligating brackets favor a higher colonization of Streptococcus mutans25,26 and accumulate more biofilm compared with conventional brackets with steel wire ligation.28 Also, there is some evidence that the amount of debris is associated with frictional force during orthodontic sliding mechanics.17,18,27 Thus, the changes arising from intraoral exposure could explain the different behavior of self-ligated brackets since their better in vitro efficiency21 has not been proven in clinical trials.22–24

The frictional force of conventional and self-ligating brackets increased by 0.52 N (47%) and 0.21 N (191%), respectively, after clinical use for 8 weeks. This finding showed that self-ligating brackets suffered a higher percentage increase in friction than conventional brackets. On the other hand, the friction increase was 0.31 N higher in the conventional ligated brackets (Table 3).

Our results confirm the well-established knowledge21 that as-received self-ligating brackets have a lower level of friction when compared with as-received conventional brackets. Regarding the increase of friction after short-term intraoral aging, our results pointed out a similar behavior between conventional and self-ligated brackets (ie, both bracket types showed increasing friction). Therefore, our results fail to establish that the consequences of exposure to the intraoral environment would be a reason for the lack of difference in clinical effectiveness between self-ligating and conventional brackets. This result indicates that the well-known similar clinical behavior between self-ligated and conventional brackets22–24 appears to be mainly associated with biological mechanisms of tooth movement, rather than changes resulting from exposure to the intraoral environment. We suggest further studies to evaluate the long-term effect of intraoral aging on self-ligating brackets.

Even though higher debris accumulation was observed in self-ligating brackets, our study evaluated only one type of self-ligating bracket. The slots of this particular bracket are not completely closed; therefore, they do not allow a major accumulation of debris. Further studies are necessary to evaluate the cumulative changes in friction of other designs of self-ligating brackets after clinical use.

Using a similar methodology, a previous investigation showed an increase of 20.8% in the friction force when orthodontic wires are exposed to the oral environment for 8 weeks. In this study, not only the wires but also the bracket-wire set was aged for 8 weeks. Our findings showed a greater increase in frictional force (47%). Thus, it seems reasonable to believe that the accumulation of debris, not only in orthodontic wire but also in the bracket slot, produces a significant increase in friction force. Thus, if cleaning methods for orthodontic wires were effective in reducing the frictional force,18 it would be interesting to evaluate the effect of some method for cleaning orthodontic brackets.

CONCLUSION

Self-ligating and conventional brackets showed a significant increase in debris and friction after intraoral exposure for 8 weeks. Accumulation of debris was higher for self-ligating brackets.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burstone CJ, Frazin-Nia F. Production of low-friction and colored TMA by ion implantation. J Clin Orthod. 1995;29:453–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drescher D, Bouravel C, Schumach HA. Frictional forces between bracket and arch wire. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1989;96:397–404. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(89)90324-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Husmann P, Bourauel C, Wessinger M, Jager A. The frictional behavior of coated guiding archwires. J Orofacial Orthop. 2002;63:199–211. doi: 10.1007/s00056-002-0009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kusy RP, Whitley JQ, Prewitt MJ. Comparison of the frictional coefficients for selected archwire-bracket slot combinations in the dry and wet states. Angle Orthod. 1991;61:293–302. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1991)061<0293:COTFCF>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaughan JL, Duncanson MG, Jr, Nanda RS, Currier GF. Relative kinetic frictional forces between sintered stainless steel brackets and orthodontic wires. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1995;107:20–27. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(95)70153-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wichelhaus A, Geserick M, Hibst R, Sander FG. The effect of surface treatment and clinical use on friction in NiTi orthodontic wires. Dent Mater. 2005;21:938–945. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andreasen GF, Quevedo FR. Evaluation of friction forces in the 0.022 × 0.028 edgewise bracket in vitro. J Biomech. 1970;3:151–160. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(70)90002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickson JA, Jones SP, Davies EH. A comparison of the frictional characteristics of five initial alignment wires and stainless steel brackets at three bracket to wire angulations—an in vitro study. Br J Orthod. 1994;21:15–22. doi: 10.1179/bjo.21.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angolkar PV, Kapila S, Duncanson MG, Jr, Nanda RS. Evaluation of friction between ceramic brackets and orthodontic wires of four alloys. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1990;98:499–506. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(90)70015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ireland AJ, Sherriff M, McDonald F. Effect of bracket and wire composition on frictional forces. Eur J Orthod. 1991;13:322–328. doi: 10.1093/ejo/13.4.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bednar JR, Gruendeman GW, Sandrik JL. A comparative study of frictional forces between orthodontic brackets and arch wires. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1991;100:513–522. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(91)70091-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sims AP, Waters NE, Birnie DJ, Pethybridge RJ. A comparison of the forces required to produce tooth movement in vitro using two self-ligating brackets and a pre-adjusted bracket employing two types of ligation. Eur J Orthod. 1993;15:377–385. doi: 10.1093/ejo/15.5.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor NG, Ison K. Frictional resistance between orthodontic brackets and archwires in the buccal segments. Angle Orthod. 1996;66:215–222. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1996)066<0215:FRBOBA>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kusy RP, Whitley JQ, Mayhew MJ, Buckthal JE. Surface roughness of orthodontic archwires—via laser spectroscopy. Angle Orthod. 1988;58:33–45. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1988)058<0033:SROOA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Downing A, McCabe JF, Gordon PH. The effect of artificial saliva on the frictional forces between orthodontic brackets and archwires. Br J Orthod. 1995;22:41–46. doi: 10.1179/bjo.22.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frank CA, Nikolai RJ. A comparative study of frictional resistances between orthodontic bracket and arch wire. Am J Orthod. 1980;78:593–609. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(80)90199-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marques ISV, Araujo AM, Gurgel JA, Normando D. Debris, roughness and friction of stainless steel archwires following clinical use. Angle Orthod. 2010;80:521–527. doi: 10.2319/081109-457.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Normando D, Araújo AM, Marques ISV, Dias CGBT, Miguel JAM. Archwire cleaning after intraoral ageing: the effects on debris, roughness, and friction. Eur J Orthod. 2013;35:223–229. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjr104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turnbull NR, Birnie DJ. Treatment efficiency of conventional vs self-ligating brackets: effects of archwire size and material. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;131:395–399. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Redlich M, Mayer Y, Harari D, Lewinstein I. In vitro study of frictional forces during sliding mechanics of “reduced-friction” brackets. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;124:69–73. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(03)00238-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi S, Lee S, Cheong Y, Park K-H, Park H-K, Park Y-G. Ultrastuctural effect of self-ligating bracket materials on stainless steel and superelastic NiTi wire surface. Microsc Res Tech. 2012;75:1076–1083. doi: 10.1002/jemt.22033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ong E, McCallum H, Griffin MP, Ho C. Efficiency of self-ligating vs conventionally ligated brackets during initial alignment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;138:e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johansson K, Lundström F. Orthodontic treatment efficiency with self-ligating and conventional edgewise twin brackets: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Angle Orthod. 2012;82:929–934. doi: 10.2319/101911-653.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miles PG. Self-ligating vs conventional twin brackets during en-masse space closure with sliding mechanics. Am J Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132:223–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nascimento LEAG, Pithon MM, Santos RL, et al. Colonization of Streptococcus mutans on esthetic brackets: self-ligating vs conventional. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2013;143:s72–s77. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pithon MM, Santos RL, Nascimento LE, Ayres AO, Alviano D, Bolognese AM. Do self-ligating brackets favor greater bacterial aggregation. Br J Oral Science. 2011;10:208–212. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ribeiro AA, Mattos CT, Ruellas AC, Araújo MT, Elias CN. In vivo comparison of the friction forces in new and used brackets. Orthodontics (Chic) 2012;13:e44–e50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garcez AS, Suzuki SS, Ribeiro MS, Mada EY, Freitas AZ, Suzuki H. Biofilm retention by 3 methods of ligation on orthodontic brackets: a microbiologic and optical coherence tomography analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;14:e193–e198. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2011.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]