Abstract

Objective:

To compare the short-term skeletal and dental effects of two-phase orthodontic treatment including either a Twin-block or an XBow appliance.

Materials and Methods:

This was a retrospective clinical trial of 50 consecutive Class II cases treated in a private practice with either a Twin-block (25) or XBow (25) appliance followed by full fixed orthodontic treatment. To factor out growth, an untreated Class II control group (25) was considered.

Results:

A MANOVA of treatment/observation changes followed by univariate pairwise comparisons showed that the maxilla moved forward less in the treatment groups than in the control group. As for mandibular changes, the corpus length increase was larger in the Twin-block group by 3.9 mm. Dentally, mesial movement of mandibular molars was greater in both treatment groups. Although no distalization of maxillary molars was found in either treatment group, restriction of mesial movement of these teeth was seen in both treatment groups. Both treatment groups demonstrated increased mandibular incisor proclination with larger increases for the XBow group by 3.3°. The Wits value was decreased by 1.6 mm more in the Twin-block group. No sex-related differences were observed.

Conclusions:

Class II correction using an XBow or Twin-block followed by fixed appliances occurs through a relatively similar combination of dental and skeletal effects. An increase in mandibular incisor inclination for the XBow group and an increased corpus length for the Twin-block group were notable exceptions. No overall treatment length differences were seen.

Keywords: Cephalometry, Class II division 1 malocclusion, Retrospective clinical trial, Twin-block, XBow

INTRODUCTION

The Twin-block appliance has been used as a Class II corrector of choice for decades and has been reported to be one of the most efficient compliance-dependent Class II correctors, based on its ability to induce mandibular elongation.1 The XBow is a relatively new Class II-correcting appliance that provides clinicians with a compliance-free alternative for mild to moderate Class II treatments.2

Class II growth modification or molar correction with either appliance (Twin-block or XBow) is usually followed by full bonding of the permanent dentition for occlusal detailing. Treatment outcomes after comprehensive orthodontic treatment, wherein either of the two appliances were utilized for phase I growth modification/molar correction, have not been previously compared. Treatment outcomes comparing compliance-free (XBow) to compliance-dependent (Twin-block) treatment could be of interest to the clinician. The present retrospective study investigated skeletal and dental differences after comprehensive orthodontic care in which either the XBow or the Twin-block was initially used for growth modification/molar correction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics approval for this study was granted by the Health Research Ethics Board from the University of Alberta (Pro00023805). Using data from previously published studies,3,4 we carried out a sample-size calculation using the Wits appraisal as the main outcome variable. The threshold for a clinically significant difference in Wits measurement attributable to treatment is not readily agreed upon in the literature. For this study, a change twice the magnitude of the method error was considered clinically significant. Related cephalometric studies report method errors to be no larger than 1 mm or 1°. The smallest detectable meaningful change of Wits was chosen to be 2 mm for the purpose of sample size calculation. Detection of a 2-mm change in the Wits appraisal at a power of 80% and at a significance level of 0.05 would require 23 patients per group. Therefore, 50 consecutively treated patients from a private practice were included in this retrospective study.

Inclusion criteria:

patients receiving phase I Twin-block or XBow appliance treatment, followed by phase II full fixed orthodontic treatment,

bilateral end-to-end or Class II molar relationship,

mild crowding (less than 5 mm per dental arch—suggestive of nonextraction treatment),

late mixed dentition or early permanent dentition (ages 10–14 at start of treatment).

Exclusion criteria:

patients requiring extraction and/or orthognathic surgery,

syndromic patients.

The XBow appliance is a fixed Class II corrector that incorporates either Forsus (3M Unitek, Monrovia, Calif) or Espirit (Opal Orthodontics, Sandy, Utah) springs and is used as a phase I appliance for the treatment of Class II discrepancies. The XBow appliance consists of a maxillary hyrax expander with bands on the first premolars and first molars. If second molars are fully erupted, then occlusal rests are incorporated. The mandibular portion of the XBow has labial and lingual bows, bands on the first molars, and occlusal rests on the first premolars and second molars (when erupted). The two appliance portions are connected with Class II fixed springs attached to headgear tubes on maxillary first molar bands and hooked on the mandibular labial bow in the canine or premolar area. The springs are activated every 6 weeks by moving the Gurin locks (3M Unitek, Monrovia, Calif) distally on the mandibular labial bow. Overcorrection is indicated due to the anticipated dental nature of the changes. It is suggested that no phase II treatment be initiated until dental relapse has occurred (usually after 3–4 months). This allows for a treatment plan based on a more stable occlusion.

The Twin-block appliance consists of maxillary and mandibular bite blocks with inclined occlusal planes that interlock and guide the mandible downward and forward. The maxillary portion has acrylic blocks that cover the molars and second premolars (or primary molars). The mandibular portion has acrylic blocks that cover the first premolars (or primary molars). Neither incisal capping nor cementation of the Twin-block was used in this sample. Vertical maxillary block trimming was done when indicated. Full-time wear was recommended.

Phase II was carried out using 0.022 × 0.028-inch edgewise brackets with the MBT prescription. Both clinicians used an archwire sequence of round (0.016- or 0.018-inch) heat-activated NiTi followed by 0.016 × 0.022-inch NiTi for alignment, with progression to 0.018 × 0.025-inch stainless steel for leveling and 0.019 × 0.025-inch beta-titanium for finishing. Interarch Class II or finishing elastics were used if needed.

Lateral cephalograms were taken prior to treatment and also immediately after treatment. Pretreatment cephalometric radiographs were taken with either a General Electric/Instrumentarium OC100D (Instrumentarium Imaging, Milwaukee, Wis) or a Sirona OrthophosDS (Sirona, Munich, Germany). All posttreatment images were taken with the Sirona. This latter was due to a change in the cephalometric unit in private practice. All lateral radiographs were uploaded into Dolphin imaging software, version 11.5 (Dolphin, Chatsworth, Calif) and traced using a custom cephalometric analysis, which included 10 linear and 3 angular variables.

To account for the effect of natural growth, which would occur regardless of treatment, a control group consisting of untreated individuals with Class II malocclusion was obtained from the Burlington Growth Center. The control group was matched to the treatment groups with regard to age and gender. Lateral cephalometric radiographs of the control group were taken with a film-based x-ray machine manufactured by Keleket (Covington, Ky) in the 1950s and ′60s; therefore, the lateral images of this group were manually traced on tracing paper using the same, above-mentioned custom analysis. All linear and angular measurements were recorded to the closest 0.5 mm and 0.5°, respectively. To correct for magnification, the manufacturer's reported magnification of 9.84% was used.

Reproducibility

To confirm reproducibility, 21 randomly selected lateral images (7 images from each group) were traced three times. The digital treatment group images were retraced at 4-week intervals. The control group manual tracings were, however, repeated in a random order over a 2-day period. Control group lateral cephalograms from the Burlington Growth Centre could not be removed from the facility and therefore all had to be traced over a 2-day period. The intraclass correlation (ICC) coefficients were calculated to assess reproducibility, and measurement errors were calculated using Dahlberg's formula.

Statistical Analysis

Assumptions for parametric tests were met. First, starting values of all three groups were compared using a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) for the T1 (pretreatment) data. To evaluate treatment/observation changes, a second MANOVA was carried out for the T2–T1 data. Normality and equal variance assumptions were checked for; MANOVA is robust to deviations from normality and equal variance. Since the groups were not equal at baseline, tests of univariate analysis of covariance were used to account for differences in starting characteristics. Post hoc Bonferroni tests were then used for pairwise comparison of intergroup differences. All statistical tests were performed using PASW Statistics 18 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill) using a significance level of 0.05.

RESULTS

ICC values were all above .900, with their confidence intervals ranging between .818 and .976, indicating very high agreement between the three sets of measurements. Dahlberg's measurement error ranged between 0.8 mm for ANPerp and 1.6 mm for Co-Pog. The ICC values and measurement errors were similar to values reported in the literature for cephalometric evaluations. The first set of repeat measurements for all groups was used in the study because the reliability values were considered excellent.

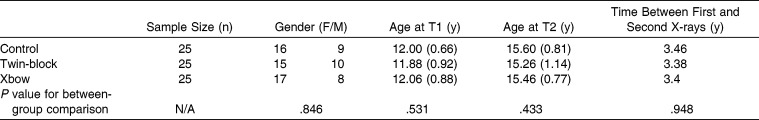

Basic demographic characteristics were compared. No major differences were identified. Samples of all three groups were matched regarding sex and age at both pre- and posttreatment. Age at time 1 (T1) was close to 12.0 years and close to 15.5 years at time 2 (T2; Table 1)

Table 1.

Subjects' Demographics

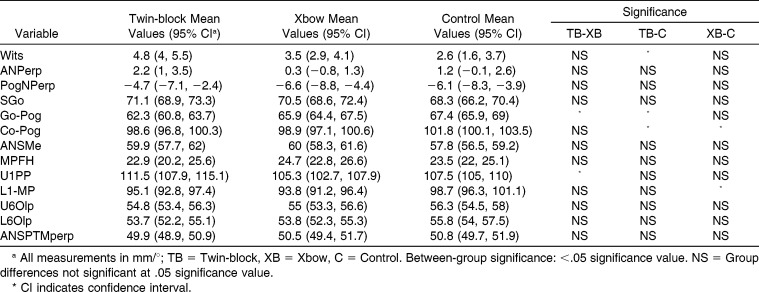

Mean values for the evaluated cephalometric variables at T1 are presented in Table 2. Differences between the groups at T1 were (1) mandibular length (Go-Pg) was approximately 3.5 mm shorter in the TB group than in the XBow group, (2) maxillary incisor inclination (U1PP) was approximately 6° more proclined in the TB group than in the XBow group, and (3) the control group had a longer mandibular dimension (measured from condyle to chin) by approximately 2 mm compared with the treatment groups. Therefore, in evaluating the treatment effects, these baseline differences were accounted for by incorporating the pretreatment values into the final statistical model.

Table 2.

Comparison of T1 Valuesa

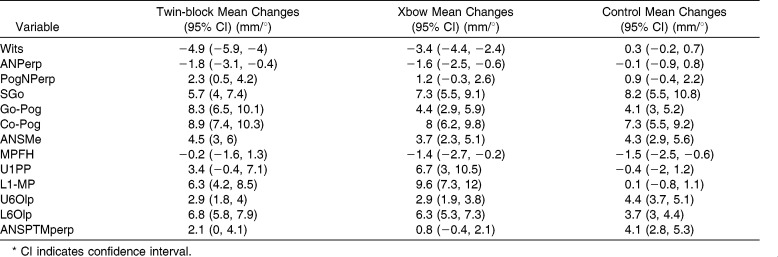

Mean cephalometric variable changes between T1 and T2 are presented in Table 3. A MANOVA was run for pretreatment values with group and sex as factors. The interaction term between group and sex was not significant (P = .272); therefore, the model was reduced and run without the interaction term. With the reduced model, sex had no significant effect (P = .296). Significant group differences were found for Wits (P = .002), Go-Pog (P < .01), Co-Pog (P = .012), U1-PP (P = .011), and L1-MP (P = .014).

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics of Treatment/Observation (T2–T1) Changes

A MANOVA of treatment/observation changes (T2–T1) was run with the interaction term (Group*Sex). The interaction term was not significant (P = .090); therefore, the model was reduced and run without the interaction term. The reduced model found a multivariate significant effect for Group (P < .001), and no significant effect for Sex (P = .086). Due to unequal baseline values, as discussed above, follow-up univariate analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) were used. ANCOVA found significant treatment effects for Group for Wits (P < .001), ANPerp (P = .029), Go-Pog (P = .009), U1PP (P = .001), L1-MP (P < .001), U6Olp (P = .005), L6Olp (P = .001), and ANSPTMperp (P = .006). Pairwise comparisons showed that significant differences existed between the control group and both Twin-block and XBow groups for Wits (P < .001; P < .001), ANPerp (P = 0.019; P = 0.026), Go-Pog (P = .009, P = .046), U1PP (P = .002; P = .008), L1-MP (P = .001; P = .000), U6Olp (P = .014; P = .015), L6Olp (P = .001; P = .012), and ANSPTMperp (P = .035; P = .009), respectively.

Wits reduction (T2–T1) was 5.2 mm and 3.7 mm larger, respectively, for the Twin-block and XBow groups compared with the control group; the ANPerp increase was 1.7 mm and 1.5 mm less in the Twin-block and XBow groups, respectively, than in the control group. The Go-Pog increase was 4.2 mm and 0.3 mm more in the Twin-block group compared with the XBow and control groups, respectively. U1PP was increased in the Twin-block and XBow groups by 3.8° and 7.1°, respectively, more than in the control group, whereas the L1-MP increase in the Twin-block and XBow groups was 6.2° and 9.5° larger, respectively, than in the control group. The increase of U6Olp in the control group was 1.5 mm more than in the Twin-block and XBow groups, whereas the L6Olp increase in the control group was 3.1 mm and 2.6 mm less than in the Twin-block and XBow groups, respectively.

No differences (values are ± SD) were found for time in active appliances in phase I (TB—9.9 ± 5.4 months vs XB—8.2 ± 5.1 months, P = 0.138—t student); in phase II (TB—23.1 ± 7.1 months vs XB—22.0 ± 3.7 months, P = 0.194—t student); or time between phases (TB—4.3 ± 4.4 months vs XB—3.3 ± 3.6 months). Statistically significant differences in number of appointments was identified, (TB—7.4 ± 3.3 vs XB—7.0 ± 1.7; P = 0.020—t student). No differences were identified for number of emergencies or extra appointments in phase I (TB—0.5 ± 0.9 vs XB—0.7 ± 0.8; P = 0.787—t student).

DISCUSSION

Both treatment groups produced a relatively small restriction of the normally expected mesial movement of the maxillary molars, with additional mesial movement of the mandibular molars. Incisor angulation changes reduced the overbite and overjet. Skeletally, restriction in midface growth occurred, while vertical changes were negligible. An increase in mandibular incisor inclination for the XBow group and an increased corpus length for the Twin-block group were notable exceptions between the two treatment groups.

A difference of 3°of mandibular incisor proclination between the appliances could be considered of relatively minor clinical significance. An increase in the mandibular corpus length occurred with Twin-block use, but an improvement of sagittal position of pogonion was not detected. Lack of increased pogonion projection could occur with increased vertical facial dimensions, but no vertical changes were noted. At baseline, the Wits appraisal was larger and mandibular corpus length smaller for the Twin-block group compared with the XBow group. During treatment, the changes in Wits and mandibular corpus length were both larger in the Twin-block than in the XBow group. The comparable final treatment outcome might be attributed to intergroup variance differences, proficiency of the operator, or superior performance of the Twin-block.

At pretreatment (T1), the Twin-block group presented with more severe Class II malocclusions than did the other two groups. The larger mandibular dimension in the Twin-block group at T2 may suggest a relatively increased effectiveness of this appliance during Class II correction. The severity of initial skeletal discrepancy has been suggested as affecting the efficiency of functional appliance treatment,5 but it has also been argued that larger skeletal discrepancies do not respond as favorably to functional treatment because the treatment effect cannot fully counteract the initial skeletal discrepancy.6

In contrast, overall mandibular changes (Co-Pog) were not significantly different between the groups. It is known, however, that the Co-Pog measurement can be affected by landmark identification errors (more specifically in locating condylion). Despite a larger increase of mandibular corpus length in the Twin-block group, pogonion sagittal changes did not reach statistical significance. This finding might be explained by the larger variation in the Twin-block group.

Direct comparison of the current results with those in the literature is difficult for two reasons: First, most comparable Class II studies have reported treatment changes that occur during the Class II correction phase, whereas in this study the reported changes include those produced during phase I and phase II treatment. Second, most comparable studies7–12 may have only included Class II division 1 malocclusions (not always clear from the selection criteria), whereas a proportion (18%) of the current sample could likely have been classified as Class II division 2. Therefore, the comparisons that follow must be interpreted with prudence.

A similar retrospective study13 compared the effectiveness of fixed-crown Herbst and Twin-block followed by full fixed appliances. Similar outcomes were found except for a minor increase in sagittal correction with Twin-block due to a larger increase in mandibular dimension. Caution should be exercised, as Herbst and XBow are conceptually different (Xbow is a nonprotrusive Class II corrector).2 In contrast to the Twin-block or Herbst that posture the mandible forward, the XBow does not posture the mandible out of the glenoid fossa. The patient is always able to return the condyle to the glenoid fossa on mouth closing and intercuspation. This significant difference does not seem to have altered the comparison.

Results of the present study and the Herbst/Twin-block study are similar in that the only discernible difference between the treatment groups was the increase in mandibular length with Twin-block treatment. The treatment effects of Twin-block and Herbst followed by full-fixed appliances have been reported before.6 Again, keeping the conceptual differences between the XBow and Herbst in mind, comparable treatment effects of the two appliances were reported.

Selection bias cannot be ruled out. As two clinicians treated the two groups, the treatment outcome may have been affected by interoperator variability. Selection was likely based on the clinicians' preference. An attempt to control for initial differences was done through statistical analysis.

Also, chronological ages, rather than developmental ages, were used to match the subjects. Differences in the developmental stages of the subjects at the time of treatment could have affected the findings. Although developmental age is a more accurate guide for predicting the adolescent growth spurt, a recent study14 suggests that in the absence of hand-wrist radiographs, chronological age might be the next developmental index of choice. Furthermore, it has been shown that chronological age may be an adequate indicator of development age.15

The goal of the current study was to evaluate the final outcome after completion of phase I orthodontic treatment (Twin-block or XBow) and phase II comprehensive orthodontic care. The final occlusal outcome is what clinicians consider when determining treatment success. Degree of treatment success as determined by the patient was not evaluated. In addition, the quantification of months in total treatment is important for clinical practice management purposes. No differences were noted in this regard.

Treating clinicians likely identify which patients are more likely to be cooperative with a compliance-based appliance (Twin-block) as one of the selection criteria for the appliances. This practice appeared to be successful in encouraging Twin-block patients to use the appliance. This may not be the case in all practices due to population sociodemographic characteristics.

A prospective, randomized, clinical trial is justified to overcome some of the stated limitations, but the so-called Hawthorne effect should be considered.

CONCLUSIONS

Class II correction with an XBow or Twin-block followed by orthodontic brackets and archwires is achieved by a combination of dentoalveolar and skeletal effects without vertical changes.

Although treatment results for most variables with both approaches were found to be similar, differences were identified for Wits (1.6 mm), Go-Pog (4.3 mm), and L1-MP (3.3°). The Twin-block group had a larger sagittal increase in mandibular length, while the XBow group experienced greater incisal proclination.

No overall treatment time differences were detected.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cozza P, Baccetti T, Franchi L, De Toffol L, McNamara JA., Jr Mandibular changes produced by functional appliances in Class II malocclusion: a systematic review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129:599.e1–599.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flores-Mir C, Barnett GA, Higgins DW, Heo G, Major PW. Short-term skeletal and dental effects of the Xbow appliance as measured on lateral cephalograms. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;136:822–832. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Windmiller EC. The acrylic-splint Herbst appliance: a cephalometric evaluation. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1993;104:73–84. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(93)70030-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toth LR, McNamara JA., Jr Treatment effects produced by the Twin-block appliance and the FR-2 appliance of Frankel compared with an untreated Class II sample. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1999;116:597–609. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(99)70193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antonarakis GS, Kiliaridis S. Short-term anteroposterior treatment effects of functional appliances and extraoral traction on Class II malocclusion: a meta-analysis. Angle Orthod. 2007;77:907–914. doi: 10.2319/061706-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Brien K, Wright J, Conboy F, et al. Effectiveness of treatment for Class II malocclusion with the Herbst or Twin-block appliances: a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;124:128–137. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(03)00345-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Illing HM, Morris DO, Lee RT. A prospective evaluation of bass, bionator and Twin-block appliances. Part I—the hard tissues. Eur J Orthod. 1998;20:501–516. doi: 10.1093/ejo/20.5.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lund DI, Sandler PJ. The effects of Twin-blocks: a prospective controlled study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998;113:104–110. doi: 10.1016/S0889-5406(98)70282-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris DO, Illing HM, Lee RT. A prospective evaluation of bass, bionator and Twin-block appliances. Part II—the soft tissues. Eur J Orthod. 1998;20:663–684. doi: 10.1093/ejo/20.6.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Brien K, Wright J, Conboy F, et al. Effectiveness of early orthodontic treatment with the Twin-block appliance: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Part 1—dental and skeletal effects. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;124:234–243. doi: 10.1016/S0889540603003524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sidlauskas A. The effects of the Twin-block appliance treatment on the skeletal and dentolaveolar changes in Class II division 1 malocclusion. Medicina (Kaunas) 2005;41:392–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jena AK, Duggal R, Parkash H. Skeletal and dentoalveolar effects of Twin-block and bionator appliances in the treatment of Class II malocclusion: a comparative study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130:594–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schaefer AT, McNamara JA, Jr, Franchi L, Baccetti T. A cephalometric comparison of treatment with the Twin-block and stainless steel crown Herbst appliances followed by fixed appliance therapy. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004;126:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mellion ZJ, Behrents RG, Johnston LE., Jr The pattern of facial skeletal growth and its relationship to various common indexes of maturation. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2013;143:845–854. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta M, Divyashree R, Abhilash P, A Bijle MN, Murali K. Correlation between chronological age, dental age and skeletal age among monozygotic and dizygotic twins. J Int Oral Health. 2005;5:16–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]